Time zone

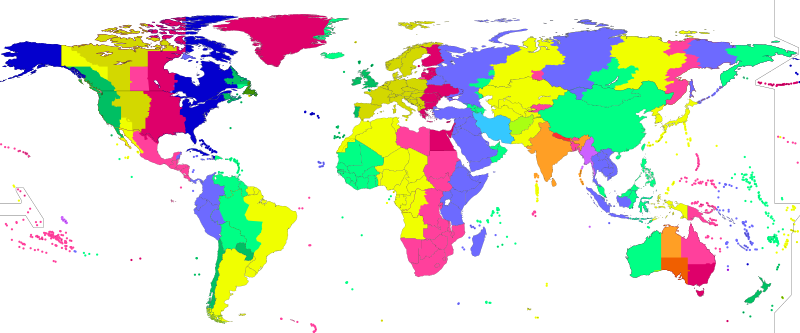

A time zone is an area which observes a uniform standard time for legal, commercial and social purposes. Time zones tend to follow the boundaries between countries and their subdivisions instead of strictly following longitude, because it is convenient for areas in frequent communication to keep the same time.

Each time zone is defined by a standard offset from Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). The offsets range from UTC−12:00 to UTC+14:00, and are usually a whole number of hours, but a few zones are offset by an additional 30 or 45 minutes, such as in India and Nepal. Some areas in a time zone may use a different offset for part of the year, typically one hour ahead during spring and summer, a practice known as daylight saving time (DST).

List of UTC offsets

In the table below, the locations that use daylight saving time (DST) are listed in their UTC offset when DST is not in effect. When DST is in effect, approximately during spring and summer, their UTC offset is increased by one hour (except for Lord Howe Island, where it is increased by 30 minutes). For example, during the DST period California observes UTC−07:00 and the United Kingdom observes UTC+01:00.

History

The apparent position of the Sun in the sky, and thus solar time, varies by location due to the spherical shape of the Earth. This variation corresponds to four minutes of time for every degree of longitude, so for example when it is solar noon in London, it is about 10 minutes before solar noon in Bristol, which is about 2.5 degrees to the west.[6]

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich, founded in 1675, established Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), the mean solar time at that location, as an aid to mariners to determine longitude at sea, providing a standard reference time while each location in England kept a different time.

Railway time

In the 19th century, as transportation and telecommunications improved, it became increasingly inconvenient for each location to observe its own solar time. In November 1840, the British Great Western Railway started using GMT kept by portable chronometers.[7][failed verification] This practice was soon followed by other railway companies in Great Britain and became known as railway time.

Around August 23, 1852, time signals were first transmitted by telegraph from the Royal Observatory. By 1855, 98% of Great Britain's public clocks were using GMT, but it was not made the island's legal time until August 2, 1880. Some British clocks from this period have two minute hands, one for the local time and one for GMT.[8]

On November 2, 1868, the British Colony of New Zealand officially adopted a standard time to be observed throughout the colony.[9] It was based on longitude 172°30′ east of Greenwich, that is 11 hours 30 minutes ahead of GMT. This standard was known as New Zealand Mean Time.[10]

Timekeeping on North American railroads in the 19th century was complex. Each railroad used its own standard time, usually based on the local time of its headquarters or most important terminus, and the railroad's train schedules were published using its own time. Some junctions served by several railroads had a clock for each railroad, each showing a different time.[11] Because of this a number of accidents occurred when trains from different companies using the same tracks mistimed their passings.[12]

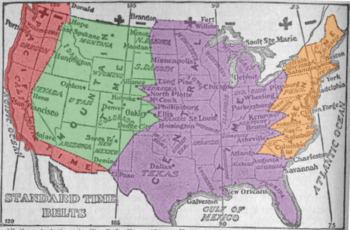

Around 1863, Charles F. Dowd proposed a system of hourly standard time zones for North American railroads, although he published nothing on the matter at that time and did not consult railroad officials until 1869. In 1870 he proposed four ideal time zones having north–south borders, the first centered on Washington, D.C., but by 1872 the first was centered on meridian 75° west of Greenwich, with natural borders such as sections of the Appalachian Mountains. Dowd's system was never accepted by North American railroads. Chief meteorologist at the United States Weather Bureau Cleveland Abbe divided the United States into four standard time zones for consistency among the weather stations. In 1879, he published a paper titled Report on Standard Time.[13] In 1883, he convinced North American railroad companies to adopt his time-zone system. In 1884, Britain, which had already adopted its own standard time system for England, Scotland, and Wales, helped gather international consent for global time. In time, the American government, influenced in part by Abbe's 1879 paper, adopted the time-zone system.[14] It was a version proposed by William F. Allen, the editor of the Traveler's Official Railway Guide.[15] The borders of its time zones ran through railroad stations, often in major cities. For example, the border between its Eastern and Central time zones ran through Detroit, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, and Charleston. It was inaugurated on Sunday, November 18, 1883, also called "The Day of Two Noons",[16] when each railroad station clock was reset as standard-time noon was reached within each time zone.

The North American zones were named Intercolonial, Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific. Within a year 85% of all cities with populations over 10,000 (about 200 cities) were using standard time.[17] A notable exception was Detroit (located about halfway between the meridians of Eastern and Central time), which kept local time until 1900, then tried Central Standard Time, local mean time, and Eastern Standard Time (EST) before a May 1915 ordinance settled on EST and was ratified by popular vote in August 1916. The confusion of times came to an end when standard time zones were formally adopted by the U.S. Congress in the Standard Time Act of March 19, 1918.

Worldwide time zones

Italian mathematician Quirico Filopanti introduced the idea of a worldwide system of time zones in his book Miranda!, published in 1858. He proposed 24 hourly time zones, which he called "longitudinal days", the first centred on the meridian of Rome. He also proposed a universal time to be used in astronomy and telegraphy. However, his book attracted no attention until long after his death.[18][19]

Scottish-born Canadian Sir Sandford Fleming proposed a worldwide system of time zones in 1876 - see Sandford Fleming § Inventor of worldwide standard time. The proposal divided the world into twenty-four time zones labeled A-Y (skipping J), each one covering 15 degrees of longitude. All clocks within each zone would be set to the same time as the others, but differed by one hour from those in the neighboring zones.[20] He advocated his system at several international conferences, including the International Meridian Conference, where it received some consideration. The system has not been directly adopted, but some maps divide the world into 24 time zones and assign letters to them, similarly to Fleming's system.[21]

By about 1900, almost all inhabited places on Earth had adopted a standard time zone, but only some of them used an hourly offset from GMT. Many applied the time at a local astronomical observatory to an entire country, without any reference to GMT. It took many decades before all time zones were based on some standard offset from GMT or Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). By 1929, the majority of countries had adopted hourly time zones, though some countries such as Iran, India, Myanmar and parts of Australia had time zones with a 30-minute offset. Nepal was the last country to adopt a standard offset, shifting slightly to UTC+05:45 in 1986.[22]

All nations currently use standard time zones for secular purposes, but not all of them apply the concept as originally conceived. Several countries and subdivisions use half-hour or quarter-hour deviations from standard time. Some countries, such as China and India, use a single time zone even though the extent of their territory far exceeds the ideal 15° of longitude for one hour; other countries, such as Spain and Argentina, use standard hour-based offsets, but not necessarily those that would be determined by their geographical location. The consequences, in some areas, can affect the lives of local citizens, and in extreme cases contribute to larger political issues, such as in the western reaches of China.[23] In Russia, which has 11 time zones, two time zones were removed in 2010[24][25] and reinstated in 2014.[26]

Notation

ISO 8601

ISO 8601 is a standard established by the International Organization for Standardization defining methods of representing dates and times in textual form, including specifications for representing time zones.

If a time is in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), a "Z" is added directly after the time without a separating space. "Z" is the zone designator for the zero UTC offset. "09:30 UTC" is therefore represented as "09:30Z" or "0930Z". Likewise, "14:45:15 UTC" is written as "14:45:15Z" or "144515Z".[27] UTC time is also known as "Zulu" time, since "Zulu" is a phonetic alphabet code word for the letter "Z".[27]

Offsets from UTC are written in the format ±hh:mm, ±hhmm, or ±hh (either hours ahead or behind UTC). For example, if the time being described is one hour ahead of UTC (such as the time in Germany during the winter), the zone designator would be "+01:00", "+0100", or simply "+01". This numeric representation of time zones is appended to local times in the same way that alphabetic time zone abbreviations (or "Z", as above) are appended. The offset from UTC changes with daylight saving time, e.g. a time offset in Chicago, which is in the North American Central Time Zone, is "−06:00" for the winter (Central Standard Time) and "−05:00" for the summer (Central Daylight Time).[28]

Abbreviations

Time zones are often represented by alphabetic abbreviations such as "EST", "WST", and "CST", but these are not part of the international time and date standard ISO 8601. Such designations can be ambiguous; for example, "CST" can mean (North American) Central Standard Time (UTC−06:00), Cuba Standard Time (UTC−05:00) and China Standard Time (UTC+08:00), and it is also a widely used variant of ACST (Australian Central Standard Time, UTC+09:30).[29]

Conversions

Conversion between time zones obeys the relationship

- "time in zone A" − "UTC offset for zone A" = "time in zone B" − "UTC offset for zone B",

in which each side of the equation is equivalent to UTC.

The conversion equation can be rearranged to

- "time in zone B" = "time in zone A" − "UTC offset for zone A" + "UTC offset for zone B".

For example, the New York Stock Exchange opens at 09:30 (EST, UTC offset= −05:00). In California (PST, UTC offset= −08:00) and India (IST, UTC offset= +05:30), the New York Stock Exchange opens at

- time in California = 09:30 − (−05:00) + (−08:00) = 06:30;

- time in India = 09:30 − (−05:00) + (+05:30) = 20:00.

These calculations become more complicated near the time switch to or from daylight saving time, as the UTC offset for the area becomes a function of UTC time.

The time differences may also result in different dates. For example, when it is 22:00 on Monday in Egypt (UTC+02:00), it is 01:00 on Tuesday in Pakistan (UTC+05:00).

The table "Time of day by zone" gives an overview on the time relations between different zones.

| Time of day by zone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UTC offset | Monday | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| UTC−12:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 |

| UTC−11:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 |

| UTC−10:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 |

| UTC−09:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 |

| UTC−09:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 |

| UTC−08:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 |

| UTC−07:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 |

| UTC−06:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 |

| UTC−05:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 |

| UTC−04:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 |

| UTC−03:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 |

| UTC−03:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 |

| UTC−02:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 |

| UTC−02:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 |

| UTC−01:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 |

| UTC+00:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 |

| UTC+01:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 |

| UTC+02:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 |

| UTC+03:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 |

| UTC+03:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 |

| UTC+04:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 |

| UTC+04:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 |

| UTC+05:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 |

| UTC+05:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 |

| UTC+05:45 | 17:45 | 18:45 | 19:45 | 20:45 | 21:45 | 22:45 | 23:45 | 00:45 | 01:45 | 02:45 | 03:45 | 04:45 | 05:45 | 06:45 | 07:45 | 08:45 | 09:45 | 10:45 | 11:45 | 12:45 | 13:45 | 14:45 | 15:45 | 16:45 |

| UTC+06:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 |

| UTC+06:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 |

| UTC+07:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 |

| UTC+08:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 |

| UTC+08:45 | 20:45 | 21:45 | 22:45 | 23:45 | 00:45 | 01:45 | 02:45 | 03:45 | 04:45 | 05:45 | 06:45 | 07:45 | 08:45 | 09:45 | 10:45 | 11:45 | 12:45 | 13:45 | 14:45 | 15:45 | 16:45 | 17:45 | 18:45 | 19:45 |

| UTC+09:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 |

| UTC+09:30 | 21:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 |

| UTC+10:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 |

| UTC+10:30 | 22:30 | 23:30 | 00:30 | 01:30 | 02:30 | 03:30 | 04:30 | 05:30 | 06:30 | 07:30 | 08:30 | 09:30 | 10:30 | 11:30 | 12:30 | 13:30 | 14:30 | 15:30 | 16:30 | 17:30 | 18:30 | 19:30 | 20:30 | 21:30 |

| UTC+11:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 |

| UTC+12:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 |

| UTC+12:45 | 00:45 | 01:45 | 02:45 | 03:45 | 04:45 | 05:45 | 06:45 | 07:45 | 08:45 | 09:45 | 10:45 | 11:45 | 12:45 | 13:45 | 14:45 | 15:45 | 16:45 | 17:45 | 18:45 | 19:45 | 20:45 | 21:45 | 22:45 | 23:45 |

| UTC+13:00 | 01:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 |

| UTC+13:45 | 01:45 | 02:45 | 03:45 | 04:45 | 05:45 | 06:45 | 07:45 | 08:45 | 09:45 | 10:45 | 11:45 | 12:45 | 13:45 | 14:45 | 15:45 | 16:45 | 17:45 | 18:45 | 19:45 | 20:45 | 21:45 | 22:45 | 23:45 | 00:45 |

| UTC+14:00 | 02:00 | 03:00 | 04:00 | 05:00 | 06:00 | 07:00 | 08:00 | 09:00 | 10:00 | 11:00 | 12:00 | 13:00 | 14:00 | 15:00 | 16:00 | 17:00 | 18:00 | 19:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 | 22:00 | 23:00 | 00:00 | 01:00 |

| UTC offset | Tuesday | Wednesday | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Nautical time zones

Since the 1920s, a nautical standard time system has been in operation for ships on the high seas. As an ideal form of the terrestrial time zone system, nautical time zones consist of gores of 15° offset from GMT by a whole number of hours. A nautical date line follows the 180th meridian, bisecting one 15° gore into two 7.5° gores that differ from GMT by ±12 hours.[30][31][32]

However, in practice each ship may choose what time to observe at each location. Ships may decide to adjust their clocks at a convenient time, usually at night, not exactly when they cross a certain longitude.[33] Some ships simply remain on the time of the departing port during the whole trip.[34]

Skewing of time zones

| 1h ± 30 min behind | |

| 0h ± 30m | |

| 1h ± 30 m ahead | |

| 2h ± 30 m ahead | |

| 3h ± 30 m ahead |

Ideal time zones, such as nautical time zones, are based on the mean solar time of a particular meridian in the middle of that zone with boundaries located 7.5 degrees east and west of the meridian. In practice, however, many time zone boundaries are drawn much farther to the west, and some countries are located entirely outside their ideal time zones.

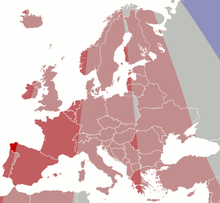

For example, even though the Prime Meridian (0°) passes through Spain and France, they use the mean solar time of 15 degrees east (Central European Time) rather than 0 degrees (Greenwich Mean Time). France previously used GMT, but was switched to CET (Central European Time) during the German occupation of the country during World War II and did not switch back after the war.[35] Similarly, prior to World War II, the Netherlands observed "Amsterdam Time", which was twenty minutes ahead of Greenwich Mean Time. They were obliged to follow German time during the war, and kept it thereafter. In the mid-1970s the Netherlands, as other European states, began observing daylight saving (summer) time.

One reason to draw time zone boundaries far to the west of their ideal meridians is to allow the more efficient use of afternoon sunlight.[36] Some of these locations also use daylight saving time (DST), further increasing the difference to local solar time. As a result, in summer, solar noon in the Spanish city of Vigo occurs at 14:41 clock time. This westernmost area of continental Spain never experiences sunset before 18:00 clock time, even in winter, despite lying 42 degrees north of the equator.[37] Near the summer solstice, Vigo has sunset times after 22:00, similar to those of Stockholm, which is in the same time zone and 17 degrees farther north. Stockholm has much earlier sunrises, though.[38]

In the United States, the reasons were more historical and business-related. In Midwestern states, like Indiana and Michigan, those living in Indianapolis and Detroit wanted to be on the same time zone as New York to simplify communications and transactions.[39]

A more extreme example is Nome, Alaska, which is at 165°24′W longitude – just west of center of the idealized Samoa Time Zone (165°W). Nevertheless, Nome observes Alaska Time (135°W) with DST so it is slightly more than two hours ahead of the sun in winter and over three in summer.[40] Kotzebue, Alaska, also near the same meridian but north of the Arctic Circle, has two sunsets on the same day in early August, one shortly after midnight at the start of the day, and the other shortly before midnight at the end of the day.[41]

China extends as far west as 73°E, but all parts of it use UTC+08:00 (120°E), so solar "noon" can occur as late as 15:00 in western portions of China such as Xinjiang.[42] The Afghanistan-China border marks the greatest terrestrial time zone difference on Earth, with a 3.5 hour difference between Afghanistan's UTC+4:30 and China's UTC+08:00.

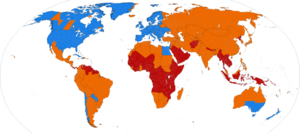

Daylight saving time

Many countries, and sometimes just certain regions of countries, adopt daylight saving time (DST), also known as summer time, during part of the year. This typically involves advancing clocks by an hour near the start of spring and adjusting back in autumn ("spring forward", "fall back"). Modern DST was first proposed in 1907 and was in widespread use in 1916 as a wartime measure aimed at conserving coal. Despite controversy, many countries have used it off and on since then; details vary by location and change occasionally. Countries around the equator usually do not observe daylight saving time, since the seasonal difference in sunlight there is minimal.

Computer systems

Many computer operating systems include the necessary support for working with all (or almost all) possible local times based on the various time zones. Internally, operating systems typically use UTC as their basic time-keeping standard, while providing services for converting local times to and from UTC, and also the ability to automatically change local time conversions at the start and end of daylight saving time in the various time zones. (See the article on daylight saving time for more details on this aspect.)

Web servers presenting web pages primarily for an audience in a single time zone or a limited range of time zones typically show times as a local time, perhaps with UTC time in brackets. More internationally oriented websites may show times in UTC only or using an arbitrary time zone. For example, the international English-language version of CNN includes GMT and Hong Kong Time,[43] whereas the US version shows Eastern Time.[44] US Eastern Time and Pacific Time are also used fairly commonly on many US-based English-language websites with global readership. The format is typically based in the W3C Note "datetime".

Email systems and other messaging systems (IRC chat, etc.)[45] time-stamp messages using UTC, or else include the sender's time zone as part of the message, allowing the receiving program to display the message's date and time of sending in the recipient's local time.

Database records that include a time stamp typically use UTC, especially when the database is part of a system that spans multiple time zones. The use of local time for time-stamping records is not recommended for time zones that implement daylight saving time because once a year there is a one-hour period when local times are ambiguous.

Calendar systems nowadays usually tie their time stamps to UTC, and show them differently on computers that are in different time zones. That works when having telephone or internet meetings. It works less well when travelling, because the calendar events are assumed to take place in the time zone the computer or smartphone was on when creating the event. The event can be shown at the wrong time. For example, if a New Yorker plans to meet someone in Los Angeles at 9 am, and makes a calendar entry at 9 am (which the computer assumes is New York time), the calendar entry will be at 6 am if taking the computer's time zone. Calendaring software must also deal with daylight saving time (DST). If, for political reasons, the begin and end dates of daylight saving time are changed, calendar entries should stay the same in local time, even though they may shift in UTC time.

Operating systems

Unix

Unix-like systems, including Linux and macOS, keep system time in Unix time format, representing the number of seconds (excluding leap seconds) that have elapsed since 00:00:00 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) on Thursday, January 1, 1970.[46] Unix time is usually converted to local time when displayed to the user, and times specified by the user in local time are converted to Unix time. The conversion takes into account the time zone and daylight saving time rules; by default the time zone and daylight saving time rules are set up when the system is configured, though individual processes can specify time zones and daylight saving time rules using the TZ environment variable.[47] This allows users in multiple time zones, or in the same time zone but with different daylight saving time rules, to use the same computer, with their respective local times displayed correctly to each user. Time zone and daylight saving time rule information most commonly comes from the IANA time zone database. In fact, many systems, including anything using the GNU C Library, a C library based on the BSD C library, or the System V Release 4 C library, can make use of this database.

Microsoft Windows

Windows-based computer systems prior to Windows 95 and Windows NT used local time, but Windows 95 and later, and Windows NT, base system time on UTC.[48][49] They allow a program to fetch the system time as UTC, represented as a year, month, day, hour, minute, second, and millisecond;[50][51] Windows 95 and later, and Windows NT 3.5 and later, also allow the system time to be fetched as a count of 100 ns units since 1601-01-01 00:00:00 UTC.[52][53] The system registry contains time zone information that includes the offset from UTC and rules that indicate the start and end dates for daylight saving in each zone. Interaction with the user normally uses local time, and application software is able to calculate the time in various zones. Terminal Servers allow remote computers to redirect their time zone settings to the Terminal Server so that users see the correct time for their time zone in their desktop/application sessions. Terminal Services uses the server base time on the Terminal Server and the client time zone information to calculate the time in the session.

Programming languages

Java

While most application software will use the underlying operating system for time zone and daylight saving time rule information, the Java Platform, from version 1.3.1, has maintained its own database of time zone and daylight saving time rule information. This database is updated whenever time zone or daylight saving time rules change. Oracle provides an updater tool for this purpose.[54]

As an alternative to the information bundled with the Java Platform, programmers may choose to use the Joda-Time library.[55] This library includes its own data based on the IANA time zone database.[56]

As of Java 8 there is a new date and time API that can help with converting times.[57]

JavaScript

Traditionally, there was very little in the way of time zone support for JavaScript. Essentially the programmer had to extract the UTC offset by instantiating a time object, getting a GMT time from it, and differencing the two. This does not provide a solution for more complex daylight saving variations, such as divergent DST directions between northern and southern hemispheres.

ECMA-402, the standard on Internationalization API for JavaScript, provides ways of formatting Time Zones.[58] However, due to size constraint, some implementations or distributions do not include it.[59]

Perl

The DateTime object in Perl supports all entries in the IANA time zone database and includes the ability to get, set and convert between time zones.[60]

PHP

The DateTime objects and related functions have been compiled into the PHP core since 5.2. This includes the ability to get and set the default script time zone, and DateTime is aware of its own time zone internally. PHP.net provides extensive documentation on this.[61] As noted there, the most current time zone database can be implemented via the PECL timezonedb.

Python

The standard module datetime included with Python stores and operates on the time zone information class tzinfo. The third party pytz module provides access to the full IANA time zone database.[62] Negated time zone offset in seconds is stored time.timezone and time.altzone attributes. From Python 3.9, the zoneinfo module introduces timezone management without need for third party module.[63]

Smalltalk

Each Smalltalk dialect comes with its own built-in classes for dates, times and timestamps, only a few of which implement the DateAndTime and Duration classes as specified by the ANSI Smalltalk Standard. VisualWorks provides a TimeZone class that supports up to two annually recurring offset transitions, which are assumed to apply to all years (same behavior as Windows time zones). Squeak provides a Timezone class that does not support any offset transitions. Dolphin Smalltalk does not support time zones at all.

For full support of the tz database (zoneinfo) in a Smalltalk application (including support for any number of annually recurring offset transitions, and support for different intra-year offset transition rules in different years) the third-party, open-source, ANSI-Smalltalk-compliant Chronos Date/Time Library is available for use with any of the following Smalltalk dialects: VisualWorks, Squeak, Gemstone, or Dolphin.[64]

Time in outer space

Orbiting spacecraft may experience many sunrises and sunsets, or none, in a 24-hour period. Therefore, it is not possible to calibrate the time with respect to the Sun and still respect a 24-hour sleep/wake cycle. A common practice for space exploration is to use the Earth-based time of the launch site or mission control, synchronizing the sleeping cycles of the crew and controllers. The International Space Station normally uses Greenwich Mean Time (GMT).[65][66]

Timekeeping on Mars can be more complex, since the planet has a solar day of approximately 24 hours and 40 minutes, known as a sol. Earth controllers for some Mars missions have synchronized their sleep/wake cycles with the Martian day, when specifically solar-powered rover activity occurs.[67]

See also

- Jet lag

- Lists of time zones

- Metric time

- Time by country

- Time in Europe

- Abolition of time zones – Replacing time zones with UTC

- World clock – Clock that displays the times in various locations around the globe

- International Date Line – Imaginary line that demarcates the change of one calendar day to the next

Notes

References

- ^ "Morocco Re-Introduces Clock Changes for Ramadan 2019". Timeanddate.com. April 19, 2019. Archived from the original on December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Time Zone in Casablanca, Morocco". Timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021.

- ^ "Time Zone in El Aaiún, Western Sahara". Timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Décret nº 2017-292 du 6 mars 2017 relatif au temps légal français" [Decree no. 2017-292 of 6 March 2017 relative to French legal time] (in French). Légifrance. March 8, 2017. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Standard Time Act 1987 No 149". New South Wales Government. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Latitude and Longitude of World Cities". Infoplease. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ "WESTMINSTER MEDICAL SOCIETY. Saturday, November 21, 1840". The Lancet. 35 (901): 383. December 1840. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)59842-0. ISSN 0140-6736. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Bristol Time". GreenwichMeanTime.com. Archived from the original on June 28, 2006. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Telegraph line laid across Cook Strait". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ "Our Time. How we got it. New Zealand's Method. A Lead to the World". Papers Past. Evening Post. p. 10. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Alfred, Randy (November 18, 2010). "Nov. 18, 1883: Railroad Time Goes Coast to Coast". Wired. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ America’s first time zone

- ^ Debus 1968, p. 2

- ^ Asimov 1964, p. 344

- ^ "Economics of Time Zones" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2012. (1.89 MB)

- ^ "The Times Reports on "the Day of Two Noons"". History Matters. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Resolution concerning new standard time by Chicago". Sos.state.il.us. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ Quirico Filopanti from scienzagiovane, Bologna University, Italy. Archived January 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gianluigi Parmeggiani (Osservatorio Astronomico di Bologna), The origin of time zones Archived August 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fleming, Sandford (1886). "Time-reckoning for the twentieth century". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (1): 345–366. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2022. Reprinted in 1889: Time-reckoning for the twentieth century at the Internet Archive.

- ^ Stromberg, Joseph (November 18, 2011). "Sandford Fleming Sets the World's Clock". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Time Zone & Clock Changes in Kathmandu, Nepal". timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Schiavenza, Matt (November 5, 2013). "China Only Has One Time Zone—and That's a Problem". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ "Russia Reduces Number of Time Zones". TimeAndDate.com. March 23, 2010. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "About Time: Huge country, nine time zones" (Video). BBC. March 22, 2011. Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ "Russian clocks to retreat again in winter, 11 time zones return". Reuters. July 2014. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "Z – Zulu Time Zone (Time Zone Abbreviation)". TimeAndDate.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ "What is UTC or GMT Time?". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ "Time Zone Abbreviations – Worldwide List", Timeanddate.com. Archived August 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Bowditch, Nathaniel. American Practical Navigator. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1925, 1939, 1975.

- ^ Hill, John C., Thomas F. Utegaard, Gerard Riordan. Dutton's Navigation and Piloting. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, 1958.

- ^ Howse, Derek. Greenwich Time and the Discovery of the Longitude. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-215948-8.

- ^ What Is Cruise Ship Time? Archived March 30, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Cruise Critic, January 8, 2020.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions Archived February 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Caribbean Adventures Roatan.

- ^ Poulle, Yvonne (1999). "La France à l'heure allemande" (PDF). Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes. 157 (2): 493–502. doi:10.3406/bec.1999.450989. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ "法定时与北京时间" (in Chinese). 人民教育出版社. Archived from the original on November 14, 2006.

- ^ Vigo, Galicia, Spain – Sunrise, Sunset, and Daylength Archived November 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Timeanddate.com.

- ^ Stockholm, Sweden – Sunrise, Sunset, and Daylength Archived February 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Timeanddate.com.

- ^ Dillion, Susannah; Kremer, Hugh. "Indiana does not belong in Eastern Time zone". Reporter-Times. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ O'Hara, Doug (March 11, 2007). "Alaska: daylight stealing time". Far North Science. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ Alaskan village to get two sunsets Friday Archived October 20, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, United Press International, August 7, 1986.

- ^ Kashgar, Xinjiang, China – Sunrise, Sunset, and Daylength Archived November 8, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Timeanddate.com

- ^ "International CNN". CNN. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "United States CNN". Cnn.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2001. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Guidelines for Ubuntu IRC Meetings". Canonical Ltd. August 6, 2008. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ "The Open Group Base Specifications Issue 7, section 4.16 Seconds Since the Epoch". The Open Group. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ "tzset, tzsetwall -- initialize time conversion information". FreeBSD 12.1-RELEASE. The FreeBSD project. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "System Time". MSDN. Archived from the original on February 27, 2007.

- ^ "System Time". Microsoft Learn. January 7, 2021. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ "GetSystemTime". MSDN. Archived from the original on February 28, 2007.

- ^ "GetSystemTime function (Windows)". Microsoft Learn. February 22, 2024. Archived from the original on April 23, 2024. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ "GetSystemTimeAsFileTime". MSDN. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007.

- ^ "GetSystemTimeAsFileTime function (Windows)". Microsoft Learn. February 22, 2024. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ "Timezone Updater Tool". Oracle Java Technologies. Archived from the original on November 24, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Joda-Time". Joda-time.sourceforge.net. Archived from the original on December 3, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "tz database". Twinsun.com. December 26, 2007. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ Java 8 Date Time

- ^ "ECMAScript 2015 Internationalization API Specification". ECMA International. June 2015. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ "Internationalization Support". Node.js v12.10.0 Documentation. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ "DateTime". METACPAN. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "DateTime". Php.net. Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "pytz module". Pytz.sourceforge.net. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ "zoneinfo module". www.python.org. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Chronos Date/Time Library Archived April 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ask the Crew: STS-111". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. June 19, 2002. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ Lu, Ed (September 8, 2003). "Day in the Life". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on September 1, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ New Tricks Could Help Mars Rover Team Live on Mars Time Archived August 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Megan Gannon, Space.com, September 28, 2012.

Sources

- Asimov, Isaac (1964). "Abbe, Cleveland". Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology: The Living Stories of More than 1000 Great Scientists from the Age of Greece to the Space Age. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc. pp. 343–344. LCCN 64016199.

- Debus, Allen G., ed. (1968). "Abbe, Cleveland". World Who's Who in Science: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Scientists from Antiquity to the Present (1st ed.). Chicago, IL: A. N. Marquis Company. ISBN 0-8379-1001-3. LCCN 68056149.

Further reading

- Biswas, Soutik (February 12, 2019). "How India's single time zone is hurting its people". BBC News. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- Maulik Jagnani, economist at Cornell University (January 15, 2019). "PoorSleep: Sunset Time and Human Capital Production" (Job Market Paper). Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- "Time Bandits: The countries rebelling against GMT" (Video). BBC News. August 14, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- "How time zones confused the world". BBC News. August 7, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- Lane, Megan (May 10, 2011). "How does a country change its time zone?". BBC News. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- "A brief history of time zones" (Video). BBC News. March 24, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- The Time Zone Information Format (TZif). doi:10.17487/RFC8536. RFC 8536.

External links

Media related to Time zones at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Time zones at Wikimedia Commons