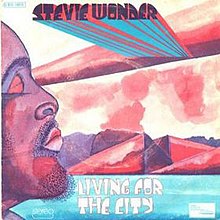

Living for the City

| "Living for the City" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Stevie Wonder | ||||

| from the album Innervisions | ||||

| B-side | "Visions" | |||

| Released | November 1973 | |||

| Recorded | December 5, 1972-April 20, 1973 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | Tamla | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Stevie Wonder | |||

| Producer(s) | Stevie Wonder | |||

| Stevie Wonder singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Living for the City" is a 1973 single by Stevie Wonder from his Innervisions album. It reached number 8 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and number 1 on the R&B chart.[3]: 635 Rolling Stone ranked the song number 104 on their 2004 list of the "500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[4]

Story and production

[edit]Born into a poor family in Mississippi, a young black man experiences discrimination in looking for work and eventually seeks to escape to New York City (alluding to the Second Great Migration) in hopes of finding a new life. Through a series of background noises and spoken dialogue, the man reaches New York by bus, but is then promptly framed for a crime, arrested, convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison.[5]: 236 [6]: 62

The basic track (electric piano and Wonder's first vocal takes) was recorded on December 5, 1972. Moog bass was overdubbed the following day. Drums, harps, and Wonder's finalized vocals were recorded on December 8, 1972. The track was left untouched until April 20, 1973, when Stevie recorded backing vocals while either slowing down or speeding up the tape, in order to make his backing vocals sound either higher or lower respectively in comparison to his natural voice[7]. Wonder played all the instruments on the song and was assisted by Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff for recording engineering and synthesizer programming.[8] Tenley Williams, writing in Stevie Wonder (2002), feels it was "one of the first soul hits to include both a political message and ... sampling ... of the sounds of the streets - voices, buses, traffic, and sirens - mixed with the music recorded in the studio."[1]: 44

Reception

[edit]Billboard described "Living for the City" as a "spectacular production of a country boy whose parents sacrifice themselves for him," and also praised the vocals and horn playing.[9]

The song has won two Grammy Awards: one at the 1974 Grammy Awards for Best Rhythm & Blues Song, and the second for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance at the 1975 Grammy Awards for Ray Charles' recording on his album Renaissance.[10]

It reached number 8 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and number 1 on the R&B chart.[3]: 635 Rolling Stone ranked the song number 104 on their 2004 list of the "500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[11]

Personnel

[edit]- Stevie Wonder – lead vocal, background vocals, Fender Rhodes, drums, Moog bass, T.O.N.T.O. synthesizer, handclaps[8]

- Calvin Hardaway (Wonder's brother); Ira Tucker Jr.; a New York police officer; attorney Jonathan Vigoda - other voices.[8]

Influence

[edit]Public Enemy sampled the phrase get in that cell, nigger in their song "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos."

Usher (or at least his producer Polow da Don) sampled the song for the hook of "Lil Freak."

Gillan covered the song, releasing it as a single which reached No. 50 in the UK, and on its 1982 album Magic.

Chart performance

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Cover versions

[edit]Dance music artist Sylvester covered the song on his 11th studio album, Mutual Attraction (1986), his major label debut album. Sylvester's "Living for the City" was released as the album's lead single and peaked at #2 on Billboard's Dance Club Play Chart.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Williams, Tenley (1 December 2001). "Inner Vision". Stevie Wonder. Overcoming Adversity. Introduction by James Scott Brady. Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-4381-2263-2. LCCN 2001047595. OCLC 47971581. OL 3952123M. Wikidata Q108381913.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "100 Greatest Funk Songs". Digital Dream Door. August 7, 2008. Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel (20 January 2006). Top R&B/Hip-Hop Singles 1942-2004. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research. ISBN 978-0898201604. LCCN 2005297809. OCLC 643640391. OL 8268962M.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time 2004: 101-200". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2008-06-20. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Steve (4 October 2013). "Playlist 2 | Down Home Rag, 1897—2005". Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings (Volume 1 and 2). Vol. 1. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-8295-9. LCCN 2012041837. OCLC 793224285. OL 26004295M. Wikidata Q108369709. Retrieved 1 September 2021 – via Internet Archive. p. 236:

The song explores modern urban realities through a narrative of a small-town migrant who arrives in New York City with bright hopes, is duped into drug running, and ends up sentenced to ten years in prison (much of the narrative is done through a dramatic playlet incorporated into the song.)

- ^ Owsinski, Bobby (1 November 2013). Bobby Owsinski's Deconstructed Hits -- Classic Rock, Vol 1: Uncover the Stories & Techniques Behind 20 Iconic Songs. Vol. 1. Alfred Music. ISBN 978-0-7390-9389-4. LCCN 2013950890. OCLC 863200803. OL 28274750M. Wikidata Q108383603 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Expanding Soul". wax-poetics. 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ a b c Hogan, Ed (n.d.). "Stevie Wonder | Living for the City". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

Along with his frequent creative partners, the engineering/synth programming duo of Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff, Wonder crafted a tantalizing track that is enthralling, vividly drawn, and deeply poignant. Cecil's film business experience played a big part in the "wide screen" feel of "Living for the City," which tells a story in a way that few songs do. Margouleff's father was the mayor of Great Neck, NY, while some of the song's "scenes" were shot (actually recorded by a portable Nagra tape recorder). Though Wonder plays all of the instruments, "Living for the City" wasn't a one man show. The singer recruited his brother Calvin, road manager Ira Tucker Jr., a New York police officer, and attorney Jonathan Vigoda. Cecil and Margouleff acted in a role as semi-directors who were trained in "the method."

- ^ "STEVIE WONDER—Living For The City". Top Single Picks (Pop). Billboard. Vol. 85, no. 44. 3 November 1973. p. 59. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 1 September 2021 – via Google Books.

Stevie's "Innervisions" LP produces this spectacular production of a country boy whose parents sacrifice themselves for him. Stevie's voice soards and glides with a gutsy reality. Lots of catchy horn, background voices and cymbals in the picture also.

- ^ "Grammy Awards: Artist - Stevie Wonder". The Recording Academy. n.d. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

BEST RHYTHM & BLUES SONG: Living For The City

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time 2004: 101-200". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2008-06-20. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Stevie Wonder — Chart history". www.billboard.com. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Stevie Wonder — German charts". www.charts.de. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "flavour of new zealand - search listener". Flavourofnz.co.nz. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- ^ "Stevie Wonder — Official UK charts". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "1974 Wrap Up" (pdf). RPM weekly. Vol. 22, no. 19. 28 December 1974. ISSN 0315-5994. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "44. LIVING FOR THE CITY—Stevie Wonder—Tamla (Motown)". Top Pop Singles. Billboard. Vol. 86, no. 52 (Billboard's Annual Talent In Action ed.). 28 December 1974. p. 8. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 1 September 2021 – via Google Books.