Litvaks

Prominent Litvak Rabbis | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 2,800[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Ashkenazi Jews Belarusian Jews, Russian Jews, Latvian Jews, Ukrainian Jews, Estonian Jews, Polish Jews | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

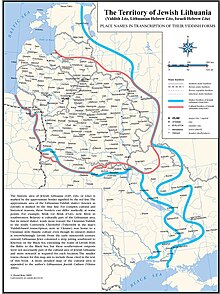

Litvaks (Yiddish: ליטװאַקעס) or Lita'im (Hebrew: לִיטָאִים) are Jews with roots in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, the northeastern Suwałki and Białystok regions of Poland, as well as adjacent areas of modern-day Russia and Ukraine). Over 90% of the population was killed during the Holocaust.[2][3][4][5] The term is sometimes used to cover all Haredi Jews who follow an Ashkenazi, non-Hasidic style of life and learning, whatever their ethnic background.[6] The area where Litvaks lived is referred to in Yiddish as ליטע Lite, hence the Hebrew term Lita'im (לִיטָאִים).[7]

No other Jew is more closely linked to a specifically Lithuanian city than the Vilna Gaon (in Yiddish, "the genius of Vilna"), Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720–1797). He helped make Vilna (modern-day Vilnius) a world center for Talmudic learning.[8] Chaim Grade (1910–1982) was born in Vilna, the city about which he would write.[9]

The inter-war Republic of Lithuania was home to a large and influential Jewish community whose members either fled the country or were murdered when the Holocaust in Lithuania began in 1941. Prior to World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population comprised some 160,000 people, or about 7% of the total population.[10] There were over 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas in Vilnius alone.[11] Census figures from 2005 recorded 4,007 Jews in Lithuania – 0.12 percent of the country's total population.[12]

Vilna (Vilnius) was occupied by Nazi Germany in June 1941. Within a matter of months, this famous Jewish community had been devastated with over two-thirds of its population killed.[13]

Based on data by Institute of Jewish Policy Research, as of 1 January 2016, the core Jewish population of Lithuania is estimated to be 2,700 (0.09% of the wider population), and the enlarged Jewish population was estimated at 6,500 (0.23% of the wider population). The Lithuanian Jewish population is concentrated in the capital, Vilnius, with smaller population centres including Klaipėda and Kaunas.[14]

Etymology

[edit]The Yiddish adjective ליטוויש Litvish means "Lithuanian": the noun for a Lithuanian Jew is Litvak. The term Litvak itself originates from Litwak, a Polish term denoting "a man from Lithuania", which however went out of use before the 19th century, having been supplanted in this meaning by Litwin, only to be revived around 1880 in the narrower meaning of "a Lithuanian Jew". The "Lithuania" meant here is the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Of the main Yiddish dialects in Europe, the Litvishe Yiddish (Lithuanian Yiddish) dialect was spoken by Jews in Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, Estonia and northeastern Poland, including Suwałki, Łomża, and Białystok.

However, following the dispute between the Hasidim and the Misnagdim, in which the Lithuanian academies were the heartland of opposition to Hasidism, "Lithuanian" came to have the connotation of Misnagdic (non-Hasidic) Judaism generally, and to be used for all Jews who follow the traditions of the great Lithuanian yeshivot, whether or not their ancestors actually came from Lithuania. In modern Israel, Lita'im (Lithuanians) is often used for all Haredi Jews who are not Hasidim (and not Hardalim or Sephardic Haredim). Other expressions used for this purpose are Yeshivishe and Misnagdim. Both the words Litvishe and Lita'im are somewhat misleading, because there are also Hasidic Jews from greater Lithuania and many Litvaks who are not Haredim. The term Misnagdim ("opponents") on the other hand is somewhat outdated, because the opposition between the two groups has lost much of its relevance. Yeshivishe is also problematic because Hasidim now make use of yeshivot as much as the Litvishe Jews.

Ethnicity, religious customs and heritage

[edit]

The characteristically "Lithuanian" approach to Judaism was marked by a concentration on highly intellectual Talmud study. Lithuania became the heartland of the traditionalist opposition to Hasidism. They named themselves "misnagdim" (opposers) of the Hasidi. The Lithuanian traditionalists believed Hassidim represented a threat to Halachic observance due to certain Kabbalistic beliefs held by the Hassidim, that, if misinterpreted, could lead one to heresy as per the Frankists.[15] Differences between the groups grew to the extent that in popular perception "Lithuanian" and "misnagged" became virtually interchangeable terms. However, a sizable minority of Litvaks belong(ed) to Hasidic groups, including Chabad, Slonim, Karlin-Stolin, Karlin (Pinsk), Lechovitch, Amdur and Koidanov. With the spread of the Enlightenment, many Litvaks became devotees of the Haskala (Jewish Enlightenment) movement in Eastern Europe pressing for better integration into European society, and today, many leading academics, scientists, and philosophers are of Lithuanian Jewish descent.

The most famous Lithuanian institution of Jewish learning was Volozhin yeshiva, which was the model for most later yeshivas. Twentieth century "Lithuanian" yeshivas include Ponevezh, Telshe, Mir, Kelm, and Slabodka, which bear the names of their Lithuanian forebears. American "offspring" of the Lithuanian yeshiva movement include Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin, Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yisrael Meir HaKohen ("Chofetz Chaim"), and Beth Medrash Govoha ("Lakewood"), as well as numerous other yeshivas founded by students of Lakewood's founder, Rabbi Aharon Kotler.

In theoretical Talmud study, the leading Lithuanian authorities were Chaim Soloveitchik and the Brisker school; rival approaches were those of the Mir and Telshe yeshivas. In practical halakha, the Lithuanians traditionally followed the Aruch HaShulchan, though today, the "Lithuanian" yeshivas prefer the Mishnah Berurah, which is regarded as both more analytic and more accessible.

In the 19th century, the Orthodox Ashkenazi residents of the Holy Land, broadly speaking, were divided into Hasidim and Perushim, who were Litvaks influenced by the Vilna Gaon. For this reason, in modern-day Israeli Haredi parlance the terms Litvak (noun) or Litvisher (adjective), or in Hebrew Litaim, are often used loosely to include any non-Hasidic Ashkenazi Haredi individual or institution. Another reason for this broadening of the term is the fact that many of the leading Israeli Haredi yeshivas (outside the Hasidic camp) are successor bodies to the famous yeshivot of Lithuania, though their present-day members may or may not be descended from Lithuanian Jewry. In reality, both the ethnic make-up and the religious traditions of the misnagged communities are much more diverse. Customs of Lithuanian non-Hasidic Jews consist of:

- Wearing of tefillin during non-sabbath days of the intermediate days of the festival chol hamoed.

- Variations in pronunciation (not practiced by most modern-day Litvaks)

- The pronunciation of the holam as /ej/ (ei).

- The shin being pronounced as /s/, making it difficult to differentiate from sin, a phenomenon known as Sabesdiker losn ('Sabbath Lingo').[16]

History

[edit]Jews began living in Lithuania as early as the 13th century.[citation needed] In 1388, they were granted a charter by Vytautas, under which they formed a class of freemen subject in all criminal cases directly to the jurisdiction of the grand duke and his official representatives, and in petty suits to the jurisdiction of local officials on an equal footing with the lesser nobles (szlachta), boyars, and other free citizens. As a result, the community prospered.

In 1495, they were expelled by Alexander Jagiellon, but allowed to return in 1503. The Lithuanian statute of 1566 placed a number of restrictions on the Jews, and imposed sumptuary laws, including the requirement that they wear distinctive clothing, including yellow caps for men and yellow kerchiefs for women.

The Khmelnytsky Uprising destroyed the existing Lithuanian Jewish institutions. Still, the Jewish population of Lithuania grew from an estimated 120,000 in 1569 to approximately 250,000 in 1792. After the 1793 Second Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Litvaks became subjects of the Russian Empire.

Litvaks in the Second World War

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) |

The Jewish Lithuanian population before World War II numbered around 160,000, or about 7% of the total population.[17] At the beginning of the war, some 12,000 Jewish refugees fled into Lithuania from Poland;[18] by 1941 the Jewish population of Lithuania had increased to approximately 250,000, or 10% of the total population.[17]

During the German invasion of June 1941, 141,000 Jews were murdered by the Nazis and Lithuanian collaborators.[19] Notable execution locations were the Paneriai woods (see Ponary massacre) and the Ninth Fort.[20]

Culture

[edit]Litvaks have an identifiable mode of pronouncing Hebrew and Yiddish; this is often used to determine the boundaries of Lita (area of settlement of Litvaks). Its most characteristic feature is the pronunciation of the vowel holam as [ej] (as against Sephardic [oː], Germanic [au] and Polish [oj]).

In the popular perception,[by whom?] Litvaks were considered to be more intellectual and stoic than their rivals, the Galitzianers, who thought of them as cold fish. They, in turn, disdained Galitzianers as irrational and uneducated. Ira Steingroot's "Yiddish Knowledge Cards" devote a card to this "Ashkenazi version of the Hatfields and McCoys".[21] This difference is of course connected with the Hasidic/misnaged debate, Hasidism being considered the more emotional and spontaneous form of religious expression. The two groups differed not only in their attitudes and their pronunciation, but also in their cuisine. The Galitzianers were known for rich, heavily sweetened dishes in contrast to the plainer, more savory Litvisher versions, with the boundary known as the Gefilte Fish Line.[22]

Genetics

[edit]The Lithuanian Jewish population may exhibit a genetic founder effect.[23] The utility of these variations has been the subject of debate.[24] One variation, which is implicated in familial hypercholesterolemia, has been dated to the 14th century,[25] corresponding to the establishment of settlements in response to the invitation extended by Gediminas in 1323, which encouraged German Jews to settle in the newly established city of Vilnius. A relatively high rate of early-onset dystonia in the population has also been identified as possibly stemming from the founder effect.[26]

Notable people

[edit]Among notable contemporary Lithuanian Jews are:

- Brothers Emanuelis Zingeris (a member of the Lithuanian Seimas) and Markas Zingeris (writer)

- Ephraim Oshry, one of the few Rabbis to survive the Holocaust

- Anatolijus Šenderovas, composer, Laureate of the Lithuanian National Award

- Arturas Bumsteinas, composer and sound artist

- Gidonas Šapiro, pop singer from the group ŽAS

- Leonidas Donskis, philosopher and essayist

- Icchokas Meras, writer

- Benjaminas Gorbulskis, composer

- Grigorijus Kanovičius, writer

- Rafailas Karpis, tenor opera singer

- David Geringas, cellist and conductor

- Arkadijus Gotesmanas, jazz percussionist

- Ilja Bereznickas, animator, illustrator, scriptwriter and caricaturist

- Adomas Jacovskis, scenographer

- Marius Jacovskis, scenographer

- Aleksandra Jacovskytė, painter

- Laurence Harvey, actor

See also

[edit]- Category:People of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- Jewish cemeteries of Vilnius

- Vilna Ghetto

- History of the Jews in Lithuania

- History of the Jews in Latvia

- Timeline of Jewish history in Lithuania and Belarus

- History of the Jews in Poland

- History of the Jews in South Africa

- Israel–Lithuania relations

- List of Lithuanian Jews

- Minhag Polin

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Rodiklių duomenų bazė". Db1.stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ "Lithuania". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved October 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Holocaust in Lithuania". Facing History and Ourselves. 13 May 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2024.

- ^ The Final Solution: Origins and Implementation. Routledge. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-0-415-15232-7.

- ^ Porat, Dina (2002). The Holocaust in Lithuania: Some Unique Aspects. Stanford University Press. p. 161.

- ^ "The Jewish Community of Lithuania". European Jewish Congress. Archived from the original on 2014-11-06. Retrieved 2014-11-06.

- ^ Shapiro, Nathan. "The Migration of Lithuanian Jews to the United States, 1880 – 1918, and the Decisions Involved in the Process, Exemplified by Five Individual Migration Stories" (PDF). Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ https://www.j2adventures.com/resources/lithuania-heroes/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/discover/yiddish-literature/focus-chaim-grade.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Lithuania". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ^ "Vilnius – Jerusalem of Lithuania". litvakai.mch.mii.lt. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Lithuanian population by ethnicity Archived 2009-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Lithuania".

- ^ Congress, World Jewish. "World Jewish Congress". World Jewish Congress. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ Joseph Telushkin. Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know About the Jewish Religion, Its People and Its History. NY: William Morrow and Co., 1991.

- ^ Glinert, Lewis, “Ashkenazi Pronunciation Tradition: Modern”, in: Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, Edited by: Geoffrey Khan. Consulted online on 24 January 2023. First published online: 2013 First print edition: 9789004176423

- ^ a b "Lithuania" (updated June 20, 2014). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ^ Levin, Dov (2010). "Lithuania". YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ^ "Lithuania Historical Background". Yadvashem.org.

- ^ "The Jerusalem of Lithuania The story of the Jewish community of Vilna". Yadvashem.org.

- ^ "Yiddish Knowledge Cards". Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "This is no fish tale: Gefilte tastes tell story of ancestry". 10 September 1999. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Slatkin, M (August 2004). "A Population-Genetic Test of Founder Effects and Implications for Ashkenazi Jewish Diseases". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 (2). American Society of Human Genetics via PubMed: 282–93. doi:10.1086/423146. PMC 1216062. PMID 15208782.

- ^ "Jewish Genetics, Part 3: Jewish Genetic Diseases (Mediterranean Fever, Tay–Sachs, pemphigus vulgaris, Mutations)". www.khazaria.com. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Durst, Ronen (May 2001), "Recent Origin and Spread of a Common Lithuanian Mutation, G197del LDLR, Causing Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Positive Selection Is Not Always Necessary to Account for Disease Incidence among Ashkenazi Jews", American Journal of Human Genetics, 68 (5), Roberto Colombo, Shoshi Shpitzen, Liat Ben Avi, et al.: 1172–1188, doi:10.1086/320123, PMC 1226098, PMID 11309683

- ^ Risch, Neil; Leon, Deborah de; Ozelius, Laurie; Kramer, Patricia; Almasy, Laura; Singer, Burton; Fahn, Stanley; Breakefield, Xandra; Bressman, Susan (1995). "Genetic analysis of idiopathic torsion dystonia in Ashkenazi Jews and their recent descent from a small founder population". Nature Genetics. 9 (2): 152–159. doi:10.1038/ng0295-152. PMID 7719342. S2CID 5922128.

References

[edit]- Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. Themes and Phenomena of the Jewish Diaspora, Volume 1. Avrum M. Ehrlich, ABC-CLIO, 2009. ISBN 978-1-85109-873-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Dov Levin, The Litvaks: A Short History of the Jews of Lithuania; translated from the Hebrew by Adam Teller. New York: Berghahn Books, 2001, ISBN 965-308-084-9

- Alvydas Nikžentaitis, Stefan Schreiner, Darius Staliūnas, Leonidas Donskis, The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews, Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2004, ISBN 90-420-0850-4

- Dovid Katz, Lithuanian Jewish Culture. Vilnius: Baltos lankos and Budapest: Central European University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-9639776517

- Dovid Katz, Seven Kingdoms of the Litvaks; Vilnius: International Cultural Program Center, 2009

- Ozer, Mark N. (2009). The Litvak Legacy. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4363-6778-3.[self-published source]

- Nathan Shapiro, The Migration of Lithuanian Jews to the United States, 1880 – 1918, and the Decisions Involved in the Process, Exemplified by Five Individual Migration Stories

- Schoenburg, Stuart; Schoenburg, Nancy (2008). Lithuanian Jewish Communities. Jason Aronson Inc. ISBN 978-1-56821-993-6.

- Sutton, Karen (2008). The Massacre of the Jews of Lithuania. Jerusalem, Israel: Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-400-5.

External links

[edit]- Official website of Jewish Community of Lithuania (in English)

- Website about Jews in Vilnius

- Collection of photos of Litvaks made in first half of 20th century

- Dovid Katz: studies on contemporary and historic Litvak culture and Litvish

- Dovid Katz: Reading list for the proposed field of Litvak Studies

- MACEVA: Lithuania Jewish Cemetery Project

- The Story of the Jewish Community in Lithuania – on the Yad Vashem website