Union of Kėdainiai

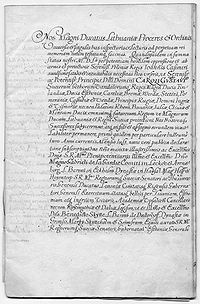

Text of the treaty in Latin | |

| Type | Establishing a Swedish–Lithuanian Union and legally dissolving the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

|---|---|

| Signed | 20 October 1655 |

| Location | Kėdainiai, Lithuania |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

The Union of Kėdainiai or Agreement of Kėdainiai (Lithuanian: Kėdainių unija, Swedish: Kėdainiai förbund) was an agreement between magnates of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the king of the Swedish Empire, Charles X Gustav, that was signed on 20 October 1655, during the Swedish Deluge of the Second Northern War.[1] In contrast to the Treaty of Kėdainiai of 17 August, which put Lithuania under Swedish protection,[1] the Swedish–Lithuanian union's purpose was to end the Lithuanian union with Poland and to set up the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a protectorate under the Swedish Crown with some of the estates being ruled by the Radziwiłł (Radvila) family.

The agreement was short-lived since the Swedish defeat at the Battles of Warka and Prostki and an uprising organised by the pro-Commonwealth nobility in Poland and Lithuania put an end to Swedish power and to the Radziwiłłs' influence.

History

[edit]Radziwiłłs' influence

[edit]

The Radziwiłł family owned vast areas of land in Lithuania and Poland, and some of its members were dissatisfied with the role of the magnates, who in Poland–Lithuania theoretically had the same rights as the Polish nobility. Eventually, the interests of the wealthy clan, known as the "Family", and the Crown began to drift apart.

Janusz Radziwiłł was the head of the Biržai line of Radziwiłłs and a leader of Lithuanian Protestants. He was a favorite of King Władysław IV, from whom he received the position of Lithuanian field hetman, but was an ardent opponent of his brother and successor Jan Kazimierz.[2][3] Shortly after his election in 1649, he supported George II Rákóczi's efforts to seize the Polish throne by making a deal with Transylvania. At the same time, he established contacts with Sweden for the first time, seeking to separate Lithuania from the Crown.[2][3] In the following years, Janusz Radziwiłł grew closer to the king, taking part in battles against the Cossacks in Ukraine.[4] He took advantage of his successes by forcing the king to appoint him voivode of Vilnius and grand hetman of Lithuania, thus making him the most important dignitary in Lithuania.[3] However, the king, wanting to limit Radziwiłł's omnipotence, made loyal Wincenty Gosiewski field hetman and treasurer of Lithuania, and divided the Lithuanian army into two divisions.[5][3] In the face of the Russian invasion, Radziwiłł refused to take offensive action and demanded that the king conclude a truce with Moscow and enter into alliance talks with Sweden. At the same time, Radziwiłł re-established contacts with George II Rákóczi urging him to claim the Polish throne and promising his support.[6] The king in turn planned to deprive him of his Hetman's office.[7]

Russian and Swedish invasion

[edit]

On October 3, 1654, Smolensk, the only major fortress capable of stopping the march of the Russian army deep into Lithuania, fell. At this point Radziwiłł entered into secret talks with Sweden seeking an agreement with them. But as he was still hoping to establish an alliance between the Commonwealth and Sweden, upon hearing of the ongoing negotiations he set out in the spring of 1655 on an expedition deep into Belarus against the Russian army.[8]

In 1654, during the Swedish-Russian invasion of Poland, known as The Deluge, two notable princes of the Radziwiłł clan, Janusz and Bogusław, began negotiations with Swedish King Charles X Gustav that were aimed at dissolving the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Union. In July 1655, Swedish troops crossed the borders of the Commonwealth. The first attack on July 24 was directed at Greater Poland. The Crown army, consisting mostly of pospolite ruszenie and devoid of a commander, capitulated before the Swedes. The capitulation, signed at Ujście, severed the relations of the Greater Poland voivodeships with the rest of the state, which had recognized Charles X Gustav as its ruler.[9] Lithuania was then in turmoil and was being attacked on two separate fronts by Russia and Sweden, and a Ukrainian peasant revolt, known as the Khmelnytsky Uprising, was spilling into the Grand Duchy's southern regions from Ukraine.

Secret talks with Sweden

[edit]

Swedish troops also entered Polish Livonia capturing Dyneburg on July 17. At the same time, Russian and Cossack armies took offensives approaching Vilnius. The Lithuanian army was few in number. It consisted of three parts: the wojsko zaciężne, the crown reinforcements and the pospolite ruszenie. The crown reinforcements constituted a considerable force of up to 5,000 men. The wojsko zaciężne was of similar size, the size of the pospolite ruszenie is unknown, but it did not represent much military value. In early July, the king ordered the Crown army to leave Lithuania and head for Prussia. This act removed any hope of an effective defense of the Grand Duchy.[10]

In view of this, on July 29, Vilnius voivode Janusz Radziwiłł, Vilnius bishop Jerzy Tyszkiewicz and Lithuanian equerry Bogusław Radziwiłł called on the Swedish army for help.[11] Swedish troops entered Lithuania essentially as allies.[12] The Lithuanian lords probably knew about the events in Ujście. They placed themselves under the protection of the Swedish king, with no obligation to swear an oath of allegiance or sever ties with the Polish Crown. The proposals envisioned a union of the three states, or only Sweden and Lithuania, if Poland found itself under alien ruler.[11] At the same time, both Radzwills demanded the creation of fiefdoms for themselves, separate from the Grand Duchy, and covering much of its territory, as well as parts of the Crown.[13] Meanwhile, the Swedes also held talks with the Russians, to whom they proposed various lines for dividing the Grand Duchy's territory between them.[14]

Earlier, on August 3, royal secretary Krzysztof Scipio del Campo of Jan Kazimierz arrived in Lithuania, with permission for the Lithuanian lords to enter into truce talks with Moscow and Sweden.[15] The proposals for talks were rejected by the tsarist army, which captured Vilnius on August 9.[16] Part of the army, having received no pay, left the ranks of the army after the fall of Vilnius.[17] On August 10 in Riga, Magnus de la Gardie accepted the Lithuanian terms brought by Gabriel Lubieniecki but not without changes, taking the Grand Duchy under his protection on behalf of the Swedish king. The Lithuanian army was to be attached to the Swedish one, the Grand Duchy was to take on the maintenance of the entire army, the Swedes were to take control of all fortresses. The question of the Grand Duchy's relationship to the Crown and Sweden and the fief principalities for the Radziwiłłs was omitted.[18][19] On August 11, he called on the tsar's commanders to stop further march deep into Lithuania, which is under the protection of the Swedish king.[20]

Act of Josvainiai

[edit]Lubieniecki returned to Janusz Radziwiłł on August 15, who was not fully satisfied with the negotiated terms, but accepted them. And with him 436 people at the Josvainiai convention, among them field hetman Wincenty Gosiewski, castellan of Samogitia Eustachy Kierdej, and Vilnius canon Jerzy Białłozor.[21] But again conditions were changed, they stipulated the separation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from Sweden, the inviolability of the union with the Crown, joint participation with the Crown in the peace talks, the non-use of Lithuanian troops against Polish ones, only temporary surrender of fortresses, and agreed to a possible union with Sweden, but on an equal basis.[22] On 17 August, Janusz Radziwiłł signed the Treaty of Kėdainiai (Instrumentum Lithuanicae deditionis), which placed the Grand Duchy under Swedish protection.[1][19] The nobility gathered in Braslaw, 116 in number, also approved the act, along with 38 exulants, 3 clergymen and 3 townsmen.[23] A number of lords, however, refused to endorse the act, among them the bishop of Samogitia, Piotr Parczewski, and the starosta of Samogitia, Jerzy Karol Hlebowicz.[23] Similarly, the nobility gathered around Grodno rejected the act of Josvainiai, remaining loyal to John II Casimir.[23] Soldiers who denounced obedience to the hetmans, as well as the nobility of Brest voivodeship, formed a confederation on August 23 in defense of the Fatherland and King John II Casimir in Virbalis, led by voivode of Witebsk Paweł Sapieha.[24]

Eventually, most of the Polish-controlled Lithuanian army surrendered to the Swedes, and the state collapsed. Most of the Crown of Poland, along with west of Lithuania, was occupied by Swedish forces, and the Russians seized most of Lithuania (except Samogitia and parts of Suvalkija and Aukštaitija). The August 17 act was not approved by the Swedes, who did not want war with Moscow, but with the Crown. Nonetheless, the Swedes moved their troops led by Gustaf Adolf Lewenhaupt into the strongholds of Biržai and Radviliškis. On September 17, Bengt Skytte arrived in Kėdainiai. Negotiations on a new treaty began.[25]

Treaty of Kėdainiai

[edit]Despite the officially proclaimed protection of the Swedish king, the Moscow army continued its march deep into Lithuania, occupying Kaunas (August 16) and Grodno (August 18). Moscow then demanded the renunciation of its claims to Lithuania, in exchange for a guarantee of the inviolability of Courland and Prussia.[26] At the same time, Moscow's deputy Vasily Likhariev arrived in Kėdainiai on August 30, promising to preserve rights, property and religious freedom in exchange for surrender to the tsar.[26] Janusz Radziwiłł rejected these proposals, giving the existing agreement with Sweden as the reason. Field hetman Wincenty Gosiewski was of different opinion, he was ready to make territorial concessions in exchange for the Commonwealth's anti-Swedish alliance with Moscow.[26] Nothing came of the talks, and on September 9 the tsar adopted the title of Grand Duke of Lithuania.[26]

On October 10, Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie arrived in Kėdainiai in an attempt to force the nobility to sign the final agreement. Janusz Radziwiłł's position was becoming weaker and weaker, he himself was constrained by private deals with the Swedes, and he was losing supporters. The Samogitian nobility, gathered in Kėdainiai, formed a confederation manifesting their separateness.[27] Bishop Jerzy Tyszkiewicz was away in Königsberg, and Bogusław Radziwiłł in his estates in Podlachia. On September 29, 1655, the army loyal to Janusz Radziwiłł, Cyprian Paweł Brzostowski in his letter to Bogusław Radziwiłł estimates at "under a thousand"; at the time, these were exclusively foreign contingents.[28] Particularly painful for the hetman was the departure from the ranks of his army by the hussar and armoured banners, but these returned to his command later and served him until his death.[29]

On 20 October 1655, Janusz Radziwiłł signed an agreement with the Swedes at his castle at Kėdainiai. According to the treaty, signed by over 1,000 members of the Lithuanian nobility, the Polish–Lithuanian Union was declared null and void. In exchange for military assistance against Russia, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania would become a protectorate of Sweden, with a personal union joining both states. In Lithuania, the king was to be represented by his governor (Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, later Bengt Skytte with the title of legate), who did not have to be a citizen of the Grand Duchy. He was to be assisted in governing by deputies, three from each powiat. The armies were to be united, the nobility lost the right to free election and influence over declaring war and making peace. Other rights and religious freedoms were preserved.[27] In addition, The Family would be given two sovereign principalities carved from its lands within the Grand Duchy, and the Lithuanian nobility would retain its liberties and privileges. Janusz Radziwiłł signed a private agreement with the Swedes, under which he received large territorial concessions and revenues; his nephew Bogusław similarly, but on a smaller scale.[30]

Aftermath

[edit]The signing of the Kėdainiai Treaty strengthened Swedish rule in Lithuania in the short term and weakened the forces loyal to the Commonwealth and John II Casimir. King John II Casimir, who was staying in Silesia, took Paweł Sapieha's confederates into the pay of the Crown treasury.[31] On September 10, he granted them the traitors' estates in Lithuania. Instead of attempting to join the royal forces, they began plundering Radziwiłł's estates. They then entered into negotiations with Moscow, proposing a truce. This had little effect, and after October 20 Moscow took a further offensive, defeating Sapieha's troops.[32] At the same time, Paweł Sapieha maintained contacts with the Swedes, through the Swedish envoy Jan Fryderyk Sapieha. He eventually accepted the Swedish king's protection on December 5.[32]

Its main proponent, Janusz Radziwiłł, died only two months after it was signed, on 31 December at Tykocin Castle, which was then besieged by forces loyal to the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania, John II Casimir. The castle was soon taken by Paweł Jan Sapieha, who immediately succeeded Janusz Radziwiłł to the office of Grand Hetman of Lithuania.

The tide of the war soon turned and a popular uprising in Poland broke the power of the Swedish army. The Swedish occupation of Lithuania sparked a similar uprising in Lithuania. The Swedish defeat and the eventual retreat from the territories of the Commonwealth abruptly ended the plans of Janusz's cousin Bogusław, who lost his army in the Battle of Prostki and died in exile in Königsberg on 31 December 1669.

With the passing of both cousins, the Radziwiłł family fortunes waned. Bogusław became commonly known as Gnida ("Louse") by his fellow nobles, and Janusz was called Zdrajca ("Traitor"). Their treason against the Commonwealth largely overshadowed the deeds of the next generation's numerous other family members, including Michał Kazimierz Radziwiłł (1625–1680), who served faithfully against the Swedes.

Assessment

[edit]Although seen as an act of treason by contemporaries, modern views on the Swedish–Lithuanian accord differ. Some argue that the arrangement with the Swedes was made by Janusz Radziwiłł not out of greed and the political ambition, but rather out of Realpolitik. According to another theory, Janusz Radziwiłł was merely attempting to secure a strong ally against Russia. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania lacked the resources to fight a war on two fronts, and the Polish Crown, which now had its own serious problems and could supply only trifling amounts of money and military forces. However, some Lithuanian intellectuals during the National Revival, including Maironis, praised the Lithuanian nobility for trying to secede from Poland and secure the sovereignty of Lithuania.[33] In 1995, Lithuania and Sweden have celebrated the 340th anniversary of the union as a symbol of friendship and historical bonds shared by the two countries.[34]

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Frost (2000), p. 168

- ^ a b Wasilewski 1973, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Wasilewski, Tadeusz. "Janusz Radziwiłł h. Trąby". www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-11-17.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, p. 130.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, p. 131.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, p. 134.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 85.

- ^ Wisner 1976, p. 105-106.

- ^ a b Wisner 1981, p. 87.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 86.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 88-89.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, p. 135.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 89-90.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 90.

- ^ Wisner 1976, p. 104-105.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 90-91.

- ^ a b Wasilewski 1973, p. 137.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 91-92.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 93.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 92-93.

- ^ a b c Wisner 1981, p. 94.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 99-100.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 96-97.

- ^ a b c d Wisner 1981, p. 95.

- ^ a b Wisner 1981, p. 98.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, p. 139.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, p. 139-141.

- ^ Wasilewski 1973, p. 138.

- ^ Wisner 1981, p. 100.

- ^ a b Wisner 1981, p. 100-101.

- ^ Bumblauskas, A. (2005). Senosios Lietuvos istorija (1009–1795) [The History of Medieval Lithuania] (in Lithuanian). R. Paknio leidykla. 307 p. ISBN 9986-830-89-3

- ^ Gerner, Kristian (2002). The Swedish and the Polish-Lithuanian Empires and the formation of the Baltic Region. Baltic University. p. 65.

Bibliography

[edit]- Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- Kotljarchuk, Andrej (2006). In the Shadows of Poland and Russia: The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Sweden in the European Crisis of the mid-17th century. Södertörns högskola. ISBN 91-89315-63-4.

- Wasilewski, Tadeusz (1973). "Zdrada Janusza Radziwiłła w 1655 r. i jej wyznaniowe motywy". Odrodzenie I Reformacja W Polsce. XVIII.

- Wisner, Henryk (1976). "Działalność wojskowa Janusza Radziwiłła, 1648-1655" [Military activities of Janusz Radziwiłł, 1648-1655]. Rocznik Białostocki. 13: 53–109.

- Wisner, Henryk (1981). "Rok 1655 w Litwie: pertraktacje ze Szwecją i kwestia wyznaniowa". Odrodzenie I Reformacja W Polsce. XXXVI.