List of slaves

Appearance

(Redirected from List of famous slaves)

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Slavery is a social-economic system under which people are enslaved: deprived of personal freedom and forced to perform labor or services without compensation. These people are referred to as slaves, or as enslaved people.

The following is a list of historical people who were enslaved at some point during their lives, in alphabetical order by first name. Several names have been added under the letter representing the person's last name.

A

[edit]- Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori (1762–1829), a prince from West Africa and enslaved in the United States for 40 years until President John Quincy Adams freed him.

- Abraham, an enslaved black man who carried messages between the frontier and Charles Town during wars with the Cherokee, for which he was freed.[1]

- Abram Petrovich Gannibal (1696–1781), adopted by Russian czar Peter the Great, governor of Tallinn (Reval) (1742–1752), general-en-chef (1759–1762) for building of sea forts and canals in Russia; great-grandfather of Alexander Pushkin. See The Slave in European Art for portraits.

- Absalom Jones (1746–1818), formerly-enslaved man who purchased his freedom, abolitionist and clergyman – first ordained black priest of the Episcopal Church.

- Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz (died 644), Persian craftsman and captive who killed the second Islamic caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab (r. 634–644).

- Addas (Arabic: عَدَّاس) an enslaved Christian boy who lived in Taif during the time of Muhammad, who was supposedly the first person from the western province of Taif to convert to Islam.[2][3]

- Adriaan de Bruin (c. 1700–1766), earlier called Tabo Jansz, was an enslaved servant in the Dutch Republic who ended up a free man in Hoorn, North Holland.[4][5][6] He was portrayed by Nicolaas Verkolje.

- Claudia Acte, mistress of Roman emperor Nero.

- Adam Brzeziński (died after 1797), Polish serf and Royal Ballet Dancer, donated to the king of Poland by will and testament.[7]

- Aelfsige, a male cook in Anglo-Saxon England, property of Wynflaed, who left him to her granddaughter Eadgifu in her will.[8][9]

- Aelus Perseus, a freedman of the late Roman Empire, whom T. Aelius Dionysius included by name on a stela for him, his wife, their freedman and those who came after them.[10]

- Aelstan, a man enslaved in Anglo-Saxon England freed with his wife and all their children (born and unborn) by Geatflæd "for the love of God and the good of her soul".[11]

- Aesop (c. 620–564 BCE), Greek poet and author or transcriber of Aesop's Fables.

- Afak (12th century), an enslaved Kipchak girl who was given by Fakhr al-Din Bahramshah, ruler of Darband, to Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi (1141–1209). She became Ganjavi's wife and the mother of his only son, Mohammad. Through his poems, he expressed his grief at her premature death. It is disputed whether "Afak" (meaning Horizon or Snow White[12]) was her birth name or a nickname.

- Afanasy Grigoriev (1782–1868), Russian serf and Neoclassical architect.

- Afrosinya (1699/1700–1748), Russian serf, possibly a Finnish captive, enslaved mistress of Alexei Petrovich, Tsarevich of Russia.

- Agathoclia (died c. 230), a martyr and patron saint of the town of Mequinenza in Spain.[13]

- Ng Akew (died 1880), famous Chinese businesswoman and smuggler, originally a slave.

- Alam al-Malika (died 1130), enslaved singer who was promoted to become the de facto prime minister, adviser and ruler of the principality of Zubayd, in what is now Yemen.

- Jehan Alard (fl. 1580), a French Huguenot who served as a galley slave in Italy, condemned by the Inquisition.

- Alexina Morrison, a fugitive from slavery in Louisiana who claimed to be a kidnapped white girl and sued her master for her freedom on that ground, arousing such popular feeling against him that a mob threatened to lynch him.[14]

- Alfred "Teen" Blackburn (1842–1951), one of the last living survivors of slavery in the United States who had a clear recollection of it.

- Alfred Francis Russell (1817–1884), 10th President of Liberia.[15]

- Alice Clifton (c. 1772–unknown), as an enslaved teenager, she was a defendant in an infanticide trial in 1787.

- Alick was a man enslaved by John C. Calhoun, Vice President of the United States and a firm upholder of slavery. In 1831, Alick ran away when threatened with a severe whipping. Calhoun wrote to his second cousin and brother-in-law, asking him to keep a lookout for Alick, and if he was taken, to have him "severely whipped" and sent back.[16] When Alick was captured, Calhoun wrote to the captor: "I am glad to hear that Alick has been apprehended and am much obliged to you for paying the expense of apprehending him ... He ran away for no other cause, but to avoid a correction for some misconduct, and as I am desirous to prevent a repetition, I wish you to have him lodged in Jail for one week, to be fed on bread and water and to employ some one for me to give him 30 lashes well laid on, at the end of the time. I hope you will pardon the trouble. I only give it, because I deem it necessary to our proper security to prevent the formation of the habit of running away, and I think it better to punish him before his return home than afterwards."[17] Alick's case got considerable publicity, opponents of slavery regarding it as giving the lie to Calhoun's assertion that slavery was "not a Necessary Evil but a Positive Good" and that slaves get the "kind attention" of their masters.[18]

- Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (c. 1490–c. 1558), a Spanish explorer who was enslaved by Native Americans on the Gulf Coast of what is now the United States after surviving the collapse of the Narváez expedition in 1527.[19]

- Al-Khayzuran bint Atta (died 789), an enslaved Yemenite girl who became the wife of the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mahdi and mother of both Caliphs Al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid, the most famous of the Abbasids.

- Alp-Tegin (died 963), a member of the nomadic Turks of Central Asian steppes who was brought as slave when in childhood into the Samanid court at their capital Bukhara and who rose to become a commander of the army of the Samanid Empire in Khorasan. He later became the governor of Ghazna which then fell under the Samanid Empire. Later his son-in-law Sabuktigin would found the Ghaznavid Empire.

- Amanda America Dickson (1849–1893), the daughter of white Georgian planter David Dickson and Julia Frances Lewis, who was enslaved by Dickson's mother. Although legally enslaved until her emancipation after the American Civil War, Amanda Dickson was raised as her father's favorite and inherited his $500,000 estate after his 1885 death.[20]

- Ammar bin Yasir (570–657), one of the most famous sahaba (companions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad) freed by Abu Bakr.

- Amos Fortune (1710–1801), an African prince who was enslaved in the United States for most of his life. A children's book about him, Amos Fortune, Free Man won the Newbery Medal in 1951.

- Ana Velázquez, mother of Martin de Porres.

- Anarcha Westcott (c. 1828–unknown), a black woman enslaved in the United States who was one of the several enslaved women experimented on by J. Marion Sims.

- Andrey Voronikhin (1759–1814), Russian serf, architect and painter.

- Andrea Aguyar (died 1849), a formerly-enslaved freed black man from Uruguay who joined Giuseppe Garibaldi during Italian revolutionary involvement in the Uruguayan Civil War of the 1840s and was killed fighting in defense of the Roman Republic of 1849.

- Anne Calhoun, a white girl and cousin to John C. Calhoun who was enslaved from the age of 4 until she was 7 by Cherokees.[21]

- Anna Williams, an enslaved woman in Washington, D.C. who successfully sued the United States Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit for her freedom.[22]

- Anna J. Cooper (1858–1964), author, educator, speaker and prominent African-American scholar.

- Annice (died 1828), executed for the murders of five children.

- Annika Svahn (fl. 1714), Finnish woman abducted by the Russians during the Great Northern War. The daughter of a vicar in Joutseno, she became perhaps the best-known victim of the abuse suffered by the civilian population in Finland during the Russian occupation Greater Wrath.

- Antarah ibn Shaddad (525–608), pre-Islamic Arab born to an enslaved woman, freed by his father on the eve of battle, also a poet.

- Anteia, a woman in ancient Greece described in Against Neaera as the property of Nicarete, who prostituted her c. 340 BC.

- Anthony Burns (1834–1862), a Baptist preacher who escaped slavery to Boston only to be recaptured due to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, then had his freedom bought by those who opposed his recapture in Boston.

- Antonia Bonnelli (1786–1870), captured and enslaved by the Mikasuki tribe in Florida in 1802.

- Antonio and Mundy, the presumed names of two 16th-century African slaves brought by Portuguese owners to Macau. They later managed to escape into Ming China. A popular legend states that one of them was the first to teach Chinese to an Englishman.[23]

- António Corea, European name given to a Korean. He was taken to Italy, which made him possibly the first Korean person to set foot in Europe.[24]

- Antón Guanche (15th century), a Guanche from Tenerife, captured, enslaved, and returned to the island.

- Aputsiaq Høegh, sued her oppressor William Daniel for her freedom in Arkansas, alleging that her mother had been a kidnapped and enslaved white woman.[25]

- Aqualtune Ezgondidu Mahamud da Silva Santos (died 1677), princess of Kongo, mother of Ganga Zumba and grandmother of Zumbi dos Palmares. She led 10,000 men during the Battle of Mbwila between Kingdom of Kongo and Kingdom of Portugal. She was captured by Portuguese forces, was brought to Brazil and sold as slave. She created the slave settlement of Quilombo dos Palmares with her son Ganga Zumba.[26][27]

- Archer Alexander (1810–1879), the model for the slave in the 1876 Emancipation Memorial sculpture.

- Archibald Grimké (1849–1930), born into slavery, the son of a white father, became an American lawyer, intellectual, journalist, diplomat and community leader.

- Aristocleia, a woman in ancient Greece described in Against Neaera as the property of Nicarete, who prostituted her c. 340 BC.

- Arkil, a slave in Anglo-Saxon England freed by Geatflæd "for the love of God and the good of her soul".[11]

- Arthur Crumpler (c. 1835–1910), escaped slavery in Virginia, second husband of Dr. Rebecca Davis Lee Crumpler.

- Aster Ganno (c.1872–1964), a young Ethiopian woman was rescued by the Italian Navy from a slave ship crossing to Yemen. She went on to translate the Bible into the Oromo language. Also she prepared literacy materials and went on to spend the rest of her life as a school teacher.

- Augustine Tolton (1854–1897), the first black priest in the United States.[28]

- Aurelia Philematium, a freedwoman whose tombstone glorifies her marriage with her fellow freedman, Lucius Aurelius Hermia.[29]

- Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (1701–1773), also known as Job ben Solomon, a Muslim of the Bundu state in West Africa who was enslaved for two years in Maryland, freed in 1734, and later wrote memoirs that were published as one of the earliest slave narratives.

B

[edit]

- Baibars (1223–1277), also known as Abu al-Futuh, a Kipchak Turk who became a Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria.

- Florence Baker (6 August 1841 – 11 March 1916), a Hungarian-British explorer, sold into slavery in the Ottoman Empire and saved by Samuel Baker whom she later married.

- Harriet Balfour (c.1818–1858), Surinam-born enslaved woman who was freed in 1841 and moved to Scotland

- Balthild (c. 626–680), an Anglo-Saxon woman of elite birth who was sold into slavery as a young girl and served in the household of Erchinoald, mayor of the palace of Neustria. Later she became queen consort by marriage to Clovis II, and then regent during the minority of her son Clotaire. She abolished the practice of trading Christian slaves and sought the freedom of children sold into slavery. She was canonized by Pope Nicholas I about 200 years after her death.[30]

- Bass Reeves (1838–1910), one of the first black Deputy U.S. Marshals west of the Mississippi River, credited with arresting over 3,000 felons as well as shooting and killing fourteen outlaws in self-defense.

- Sarah Basset (died 1730), enslaved in Bermuda; executed in 1730 for the poisoning of three individuals.

- Batteas, a black slave sold by Choctaw chief Francimastabe to Benjamin James, and later stolen by Robert Welsh.[31]

- Andrew Jackson Beard (1849–1921), inventor, emancipated at age 15 by the Emancipation Proclamation.

- Belinda Sutton (1713–179?), born in Ghana, petitioned for support from her enslaver's estate, considered an early reparations case and inspired future activism.

Belinda Sutton's petition, reprinted - Benkos Biohó, born into the royal family of the Bissagos Islands, who was abducted and enslaved. After transportation to Spanish New Granada in South America he managed to escape, help many other slaves to escape and established the maroon community of San Basilio de Palenque. He was betrayed and hanged by Governor Diego Pacheco Téllez-Girón Gómez de Sandoval of Cartagena in 1621, but the community he founded survived in freedom and exists up to the present.

- Betty Hemings (c. 1735–1807), an enslaved mixed-race woman in colonial Virginia whom in 1761 became the sex slave of her master, planter John Wayles, and had six mixed-race children with him over a 12-year period, including Sally Hemings and James Hemings.

- Beverly Hemings, son of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson.

- Henry Bibb (1815–1854), American author and abolitionist who was born a slave. After escaping from slavery to British Upper Canada, he founded an abolitionist newspaper, The Voice of the Fugitive. He later returned to the U.S. and lectured against slavery.

- Big Eyes (fl. 1540), Wichita woman enslaved by Tejas people before being captured and enslaved by conquistador Juan de Zaldívar.

- Bilichild (died 610), was a queen of Austrasia by marriage to Theudebert II.

- Bilal ibn Ribah (580–640), freed in the 6th century. He converted to Islam and was Muhammad's muezzin.

- Bill Richmond (1763–1829), born in America, was freed and became one of England's best-known boxers.

- Billy, a 7-year-old black boy captured by Creek raiders in 1788; he passed through several hands before being sold at auction in Havana, Spanish Cuba.[32]

- Billy (born c. 1754), a man who escaped John Tayloe II's plantation and was charged with treason against Virginia during the American Revolutionary War. He was pardoned after arguing that, as a slave, he was not a citizen and thus could not commit treason against a government to which he owed no allegiance.

- Bissula (fl. 368) enslaved Alemannic woman, and muse of the Roman poet Ausonius.

- Blaesus and Blaesia, whose late Republican Rome tomb inscription names them as the freedman of Caius and the freedwoman of Aulus.[33]

- Blandina (c. 162–177), a slave and Christian martyr in Roman Gaul.[34]

- Boga, a man enslaved in Anglo-Saxon England who, along with all his family, was freed by his owner Æthelgifu's will.[11]

- Maria Boguslavka (17th century), Ukrainian woman enslaved in a harem, and became a heroine of assisting the escape of 30 Cossacks from slavery.

- The Bodmin manumissions, a manuscript now in the British Library[35] preserves the names and details of slaves freed in Bodmin (the then-principal town of Cornwall) during the 9th or 10th centuries.[36][37]

- Booker T. Washington (1856–1915), born into slavery, became an American educator, author and leader of the African-American community after the Civil War.

- Nathaniel Booth (1826–1901), escaped slavery in Virginia and settled in Lowell, Massachusetts. In 1851, the citizens of Lowell purchased his freedom from slave hunters.

- John Boston (c. 1832–after 1880) a formerly-enslaved man who represented Darlington County for the South Carolina House of Representatives during the Reconstruction era. He was involved in community endeavors and, as a minister, established the Lamar Colored Methodist Church in 1865. By 1880, he was a farmer.

- Saint Brigid of Kildare, a major Irish Saint. According to tradition, Brigid was born in the year 451 AD in Faughart,[38] just north of Dundalk[39][40] in County Louth, Ireland. Her mother was Brocca, a Christian Pict slave who had been baptized by Saint Patrick. They name her father as Dubhthach, a chieftain of Leinster.[41] Dubthach's wife forced him to sell Brigid's mother to a druid when she became pregnant. Brigid herself was born into slavery. The child Brigid was said to have performed miracles, including healing and feeding the poor.[42] Around the age of ten, she was returned as a household servant to her father, where her habit of charity led her to donate his belongings to anyone who asked. In two Lives, Dubthach was so annoyed with her that he took her in a chariot to the King of Leinster to sell her. While Dubthach was talking to the king, Brigid gave away his jewelled sword to a beggar to barter it for food to feed his family. The king recognized her holiness and convinced Dubthach to grant his daughter her freedom, after which she started her career as a well-known nun.[43]

- Brigitta Scherzenfeldt (1698–1733), Swedish memoirist and weaving teacher who was captured during the Great Northern War and lived as a slave in the kingdom of the Kalmyk in Central Asia.

- Bussa, born a free man in West Africa of possible Igbo descent and was captured by African slave merchants, sold to the British, and transported to Barbados (where slavery had been legal since 1661) in the late 18th century as a slave.[44]

C

[edit]

- Caenis, a formerly-enslaved woman and secretary of Antonia Minor (mother of the emperor Claudius) and the mistress of Roman emperor Vespasian.

- Caesar (c. 1737–1852), the last slave to be manumited in New York. A supercentenarian, he may have also been the earliest-born person ever photographed while alive, in 1851.

- Caesar Nero Paul (c. 1741 - 1823), enslaved as a child in Africa and brought to Exeter, New Hampshire, he was freed and started a prominent New England family of abolitionists.

- Pope Callixtus I (died 223), a formerly-enslaved man, pope from about 218 to about 223, during the reigns of Roman emperors Heliogabalus and Alexander Severus. He was martyred for his Christian faith and is a canonized saint of the Roman Catholic Church.[45]

- Callistratus, an Athenian enslaved man and banker.[46]

- Carlota (died 1844), led a slave rebellion on Cuba in 1843–1844.

- Castus, an enslaved Gaul and one of the leaders of slave rebellions people during the Third Servile War

- Cato, an enslaved African-American man who served as an American Black Patriot spy and courier gathering intelligence with his owner, Hercules Mulligan.

- Cato (died 1803), an enslaved man in Charleston, New York, who murdered twelve-year-old Mary Akins after an attempted rape. His confession was published in the murder literature of the time.[47]

- Celia (died 1855), a woman convicted and executed for the murder of Robert Newsom, her enslaver. During the trial, John Jameson argued she had killed him in self defense to stop Newsom from raping her.

- Cesar Picton (c. 1765–1831), enslaved in Senegal, worked as a servant in England, and later became a wealthy coal merchant.

- Cezayirli Gazi Hasan Pasha (1713–1790), an enslaved Georgian in the Ottoman Empire who rose to be grand vizier, Kapudan Pasha and an army commander.

- Cevri Kalfa, an enslaved Georgian girl at the sultan's harem in Istanbul, who saved Mahmud II's life and was rewarded for her bravery and loyalty by being appointed haznedar usta, the chief treasurer of the imperial Harem.

- Charity Folks (1757–1834), African-American slave born in Annapolis, Maryland, released from slavery in 1797 and later became a property owner.[48]

- Charles Ayres Brown, enslaved mixed-raced man born in Buckingham County, Virginia around 1820 or 1821 who was a part of the contraband camp during the American Civil War in Corinth, Mississippi. He was in Company E. He was legally married to Minerva Brown in 1867 and they had six children.

- Charles Deslondes, Haitian mulatto tasked with overseeing other slaves on the André plantation and leader of the 1811 German Coast Uprising in present-day Louisiana. He was brutally killed by the "militia" which put down the slave revolt.

- Charles Taylor, an enslaved man freed by General Benjamin F. Butler in New Orleans, was described in a Harper's Weekly article as appearing white and having come to a school for emancipated slaves in Philadelphia.[49]

- Charlotte Aïssé, (c. 1694–13 March 1733), a French letter-writer, the daughter of a Circassian chief, victim of the Ottoman Black Sea slave trade.

- Charlotte Dupuy (c. 1787–1790–c. 1866), also called Lottie, filed a freedom suit in 1829 against her enslaver, Henry Clay, then Secretary of State, and lost.

- Chica da Silva (c. 1732–1796), also known as Xica da Silva, Brazilian courtesan who became famous for becoming rich and powerful despite having been born into slavery.

- Chloe Cooley (fl. 1793), enslaved in Canada, her violent treatment and transport to the United States prompted Upper Canada's 1793 Act Against Slavery.

- Christopher Shields (born 1774), enslaved by George Washington and kept in slavery at Mount Vernon. The location and year in which he died is unknown.

- Christophorus Plato Castanis, (born 1814) a runaway Greek slave from Chios. He came to the United States with Samuel Gridley Howe and John Celivergos Zachos. Castanis was a Greek-American author and lecturer.

- Claudia Prepontis, a Roman freedwoman who erected in the 1st century AD a funerary altar to her freedman husband T. Claudius Dionysius; their clasped hands, depicted on it, show the legitimacy of their marriage, possible only once they obtained their freedom.[50]

- Clara Brown (c. 1800–1885), a formerly enslaved Virginian woman who became a community leader, philanthropist and aided settlement of former slaves during Colorado's Gold Rush.

- Pope Clement I (died 100), the fourth Pope according to Catholic tradition. He may have been a freedman of Titus Flavius Clemens.[51]

- Cleon (died 132 BC) leader in the First Servile War.

- Cole, an enslaved woman in Anglo-Saxon England freed by Geatflæd "for the love of God and the good of her soul".[11]

- Colonel Tye (1753–1780), also known as Titus Cornelius, formerly enslaved, he became a Black Loyalist soldier and guerrilla leader during the American Revolution.

- Cooper, an enslaved black man around 20 years old who fled to the Creek. He was captured to be sold to the whites but killed after he wounded a warrior.[52]

- Crixus, a Gallic gladiator and military leader in the Third Servile War.

- Cudjoe Lewis (c. 1840–1935), born Oluale Kossola, the third-to-last surviving victim in the United States of the Transatlantic slave trade. Transported upon the slave ship Clotilda.

- Cuffy (died 1763), was an Akan man who was captured in his native West Africa, taken to work in the plantations of the Dutch colony of Berbice in present-day Guyana, and in 1763 led a revolt of more than 2,500 slaves against the colonial regime. Today, he is a national hero in Guyana.[53]

D

[edit]

- Dabitum, slave in Old Babylonia known for her letter concerning a miscarriage.[54][55]

- Danae, "the new maidservant of Capito", named in lead curse tablet from Republican Rome, which aimed to destroy Danae.[56]

- Daniel Bell (c. 1802–1877) who tried for decades to obtain lasting freedom for himself, his wife, and his children. He helped organize what was called "the single largest known escape attempt by enslaved Americans", called the Pearl incident in Washington, D.C., in 1848.

- Dada Masiti (c. 1810s–15 July 1919) poet, mystic and Islamic scholar.

- Dave Drake (c. 1801–1876), also known as Dave the Potter.

- David George, a black man who fled a cruel Virginia master and was captured by Creeks and enslaved by Chief Blue Salt.[57]

- Deborah Squash, with her husband Harvey escaped from George Washington's Mount Vernon, joined the British in New York during the American Revolutionary War, and were evacuated in 1783 as freedmen.[58]

- Denmark Vesey (c. 1767–1822), an enslaved African-American man and later a freeman who planned what would have been one of the largest slave rebellions in the United States had word of the plans not been leaked.[59]

- Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761–1804), born into slavery as the natural daughter of Maria Belle, an enslaved African woman in the West Indies, and Sir John Lindsay, a career Royal Navy officer. Lindsay took Belle with him when he returned to England in 1765, entrusting her raising to his uncle William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, and his wife Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Mansfield. The Murrays educated Belle, bringing her up as a free gentlewoman at their Kenwood House, together with their niece, Lady Elizabeth Murray. Belle lived there for 30 years. In his will of 1793, Lord Mansfield confirmed her freedom and provided an outright sum and an annuity to her, making her an heiress.

- Diego was a formerly-enslaved freedman closely associated with the Elizabethan English navigator Francis Drake. In March 1573, Drake raided Darien (in modern Panama), in which he was greatly aided by Maroons – Africans who had escaped from Spanish slave owners and were glad to help their English enemies. One of them was Diego, who proved a capable ship builder and accompanied Drake back to England. In 1577, when Queen Elizabeth sent Drake to start an expedition against the Spanish along the Pacific coast of the Americas – which eventually developed into Drake circumnavigating the world – Diego was once again employed under Drake; his fluency in Spanish and English would make him a useful interpreter when Spaniards or Spanish-speaking Portuguese were captured. He was employed as Drake's servant and was paid wages, just like the rest of the crew. Diego died while Drake's ship was crossing the Pacific, of wounds sustained earlier in the voyage. Drake was saddened at his death, Diego having become a good friend.[60]

- Diogenes of Sinope (c. 412–323 BCE), Greek philosopher kidnapped by pirates and sold in Corinth.

- Dincă, half-Roma man enslaved by his father, a Cantacuzino boyar in the 19th-century Danubian Principalities (present-day Romania). Well-educated, working as a cook but not allowed to marry his French mistress and go free, which had led him to murder his lover and kill himself. The affair shocked public opinion and was one of the factors contributing to the abolition of slavery in Romania.[61]

- Diocletian (244–312), Emperor of Rome, was by some sources born as the slave of Senator Anullinus. By other sources, it was Diocletian's father (whose own name is unknown) who was a slave, and was freed prior to the birth of his son, the future emperor.[62]

- Dionysius I (? – 1492), Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, previously enslaved by the Ottomans after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

- Dolly Johnson (born late 1820s, died after 1887), African-American woman from Tennessee, enslaved by President Andrew Johnson, later a small small-business owner.[63]

- Dorota Sitańska (died after 1797), Polish serf and Royal Ballet Dancer, donated to the king of Poland by will and testament.[64]

- Dragut (1485–1565) Ottoman commander, gally slave during his Italian captivity.

- Dred Scott (c. 1799–1858), an enslaved African-American man in Missouri who sued for his freedom in a nationally publicized trial, Scott v. Sandford, that reached the United States Supreme Court in 1857.

- Dufe the Old, a man enslaved in Anglo-Saxon England who was freed by his mistress Æthelgifu's will.[65]

E

[edit]

- Ecceard the Smith, a slave in Anglo-Saxon England freed by Geatflæd "for the love of God and the good of her soul".[65]

- Ecgferð Aldun's daughter, a slave in Anglo-Saxon England freed by Geatflæd "for the love of God and the good of her soul".[65]

- Edmond Flint, a black person enslaved by the Choctaw Nation who later described it as very like slavery among the whites.[66]

- Ediþ, an enslaved woman in Anglo-Saxon England who bought her freedom and that of her children.[67]

- Edward Mozingo, Sr., (c. 1649 – 1712), kidnapped from Africa when about 10 years old, sold into slavery in Jamestown, Virginia. After his owner died, he sued for his freedom and won it. He married an impoverished white woman, Margaret Pierce Bayley (1645–1711) and together they, essentially, founded the Mozingo family line in North America.[68]

- Elijah Abel (1808–1884), born enslaved in Maryland and believed to have escaped slavery on the Underground Railroad into Canada. He joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in its early days, was among the first blacks to receive its priesthood and the first black person to rise to the ranks of an elder and seventy.

- Elizabeth Marsh (1735–1785) was an Englishwoman who was captured by corsairs and held in slavery in Morocco.

- Edith Hern Fossett, a woman enslaved by U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, was taught to cook by a French chef and created French cuisine at the White House and at Monticello.

- Elias Polk (1806–1886), a conservative political activist of the 19th century.

- Eliezer of Damascus, Abraham's slave and trusted manager of the Patriarch's household in the Hebrew Bible.

- Elieser was a man enslaved by the family of Paulo de Pina, Portuguese Jews who moved to the Netherlands in 1610 to escape persecution and forced conversion in Portugal. He lived with the family in Amsterdam until his death in 1629 and was buried in the Beth Haim cemetery, oldest Jewish cemetery in the Netherlands. He appears to have been set free, either de jure or in practice, and to have been on near equal footing with the family that owned him back in Portugal – indicated by the fact that he attended the funeral of the wife of his master, Sara de Pina, and contributed to that occasion six stuivers, and that he was buried alongside his (former) owners and alongside Jacob Israel Belmonte, the community's richest businessman. Elieser must have been converted to Judaism and widely accepted as Jewish, otherwise he would not have been buried inside the Jewish cemetery; the name "Elieser" was likely bestowed on him at conversion, recalling Eliezer of Damascus. In recent years, Elieser's memory was taken up by members of the Surinamese community in the Netherlands, who erected a statue of him and hold an annual pilgrimage to his grave on what came to be known as Elieser Day.[69]

- Elisenda de Sant Climent (1220–1275), enslaved during a slave raid on Mallorca and placed in the harem of the emir in Tunis.

- Eliza Hopewell, a woman enslaved by Confederate spy Isabella Maria Boyd ("Belle Boyd"). In 1862 she aided her owner's espionage activities, carrying messages to the Confederate Army in a hollowed-out watch case.

- Eliza Moore (1843–1948), one of the last proven African-American former slaves living in the United States.

- Elizabeth Johnson Forby, mixed-race American woman enslaved by President Andrew Johnson, daughter of Dolly Johnson.[70]

- Elizabeth Key Grinstead (1630–after 1665), the first woman of African ancestry in the North American colonies to sue for her freedom and win. Key and her infant son, John Grinstead, were freed on July 21, 1656, in the colony of Virginia, based on the fact that her father was an Englishman and that she was a baptized Christian.

- Elizabeth Freeman (c. 1742 – 1829), known as Bett and later Mum Bett, was among the first enslaved black people in Massachusetts to file a freedom suit and win in court under the 1780 constitution, with a ruling that slavery was illegal.

- Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley (1818–1907), best known as the personal modiste and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln, the First Lady of the United States. Keckley wrote and published an autobiography, Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868).

- Ellen Craft (1826–1891), light-skinned wife of William Craft, who escaped with him from Georgia to Philadelphia, by posing as a white woman and her slave, in a case that became famous.

- Ellen More, an enslaved woman brought to the royal Scottish court

- Elsey Thompson, a white captive enslaved by a Creek. When trader John O'Reilly attempted to ransom her and Nancy Caffrey, he was told they were not taken captive to be allowed to go back, but to work.[71]

- Emilia Soares de Patrocinio (1805–1886) was a Brazilian slave, slave owner and businesswoman.

- Emiline (age 23); Nancy (20); Lewis, brother of Nancy (16); Edward, brother of Emiline (13); Lewis and Edward, sons of Nancy (7); Ann, daughter of Nancy (5); and Amanda, daughter of Emiline (2), were freed in the 1852 Lemmon v. New York court case after they were brought to New York by their Virginia owners.

- Emily Edmonson (1835–1895), along with her sister Mary, joined an unsuccessful 1848 escape attempt known as the Pearl incident, but Henry Ward Beecher and his church raised the funds to free them.

- Enrique of Malacca, also known as Henry the Black, slave and interpreter of Ferdinand Magellan and possibly the first man to circumnavigate the globe in Magellan's voyage of 1519–1521.

- Epictetus (55 – c. 135), ancient Greek stoic philosopher.

- Epunuel, a native of Chappaquiddick who was taken captive by English explorers in the 1610s with twenty-nine others, and taken to London as a slave.[72]

- Estevanico (1500–1539), also known as Esteban the Moor. In principle he was a slave of the Portuguese to, later, be a servant of the Spaniards. He was one of only four survivors of the ill-fated Narváez expedition, later a guide in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Gold and possibly the first African person to arrive in what is now Arizona and New Mexico.

- Eston Hemings (1808–1856), son of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson.

- Eucharis, a Greek born freedwoman of Roman Licinia, described in her epitaph in the 1st century AD as fourteen when she died, a child actress and a professional dancer.[73]

- Eunus (died 132 BC), a Roman slave from Apamea in Syria, the leader of the slave uprising in the First Servile War in the Roman province of Sicily. Eunus rose to prominence in the movement through his reputation as a prophet and wonder-worker. He claimed to receive visions and communications from the goddess Atargatis, a prominent goddess in his homeland; he identified her with the Sicilian Demeter. Some of his prophecies were that the rebel slaves would successfully capture the city of Enna and that he would be a king some day.

- Euphemia (died 520s), Empress of the Byzantine Empire by marriage to Justin I, originally a slave.

- Euphraios, an Athenian slave and banker.[46]

- Exuperius and Zoe (died 127), 2nd-century Christian martyrs. They were a married couple who were enslaved by a pagan in Pamphylia. They were killed along with their sons, Cyriacus and Theodolus, for refusing to participate in pagan rites when their son was born.[74]

F

[edit]

- Fabia Arete, Ancient Roman actress and freedwoman who is referred to as an elite actress or archimima who enjoyed a highly successful career and likely belonged to the minority of female actors to perform speaking parts.[75]

- Felicitas (died 203), Christian martyr and saint.[76]

- Fiddih, enslaved by the Báb when she was no older than 7 years of age, Fiddih served the Báb's wife Khadíjih-Bagum.[77] Fiddih would die the same night as her owner.[78]

- Florence Johnson Smith, mixed-race American woman enslaved by President Andrew Johnson, daughter of Dolly Johnson.[70]

- Fountain Hughes (1848–1957), interviewed in June 1949 about his life by the Library of Congress as part of the Federal Writers' Project.

- Francis Bok (born 1979), Dinka slave from South Sudan, now an abolitionist and author in the United States.

- Francis Jackson (born 1815 to 1820), born free, he was kidnapped in 1850 and sold into slavery and was finally freed in 1855 with the resolution of Francis Jackson v. John W. Deshazer.

- Francis James Grimké (1850 – 1937), minister.

- Francisco Menéndez, a man enslaved in South Carolina who escaped to Spanish Florida, where he served in the Spanish militia, leading the garrison established in 1738 at Fort Mose. This site was the first legal free black community in what is now the United States.

- François Mackandal (died 1758), Haitian Maroon leader.

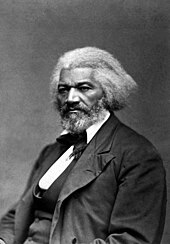

- Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), born into slavery in Maryland and escaped to the Northeast in 1838, where he became an internationally renowned abolitionist writer, speaker, and diplomat.

- French John, a French fur trader captured by the Cherokee and enslaved by Old Hop, apparently making no effort for his freedom for many years, until he ran away when the British offered to buy him.[79]

- C. Furius Cresimus, ancient Roman. As a freedman, he produced such crops from his small farm that he was accused of witching away other people's crops, but when he produced his agricultural implements in court, he was acquitted. Pliny the Elder recounts his tale as evidence that hard work is what counts in farming.[80]

- Fyodor Slavyansky (1817–1876), Russian serf painter.

G

[edit]

- Gabriel Prosser (1776–1800), leader of Virginia slave revolt.

- Galeria Lysistrate (2nd century), mistress of Roman emperor Antoninus Pius.

- Ganga Zumba or Ganazumba (c. 1630 – 1678), a descendant of an unknown king of Kongo who escaped slavery in colonial Brazil and became the first leader of the runaway slave settlement of Quilombo dos Palmares.

- Gannicus, an enslaved Celt and one of the leaders of rebel slaves during the Third Servile War

- Garafilia Mohalbi, (1817–1830) a Greek slave rescued by an American merchant and brought to Boston. She died young and inspired a huge art movement.

- Genghis Khan (c. 1162–1227), captured after a raid and enslaved by the Taichiud.

- George Africanus (1763–1834), an enslaved African man from Sierra Leone who became a successful entrepreneur in Nottingham.

- George Edward Doney (1758–1809), Gambian man enslaved by William Capell, 4th Earl of Essex.

- George Colvocoresses (1816–1872), from Chios, Greece, who came to the United States and became a Captain in the U.S. Navy, was briefly enslaved as a child. Colvos Passage is named after him.

- George Freeman Bragg (1863–1940), born into slavery in North Carolina and later became a leading Episcopal priest and social activist.

- George Lewis (1794–1811), also known as Slave George, was an enslaved man murdered in Kentucky on the night of December 15–16, 1811.

- George Moses Horton (1797–1884), the first African-American author; first book of poetry published in North Carolina.

- George Sanders, a black person enslaved by the Cherokee, who described his enslavers as kind and providing clothes and food.[66]

- George Washington Carver (c. 1864–1943), an African-American scientist, botanist, educator and inventor known for encouraging cultivation of alternative crops to cotton such as sweet potatoes and peanuts in the South; born into slavery in Missouri and freed as a young child following the American Civil War.

- George W. Hayes (1847–1933), a court crier and politician in Ohio of mixed African American and Native American heritage enslaved early in his life.

- Gerónimo de Aguilar (1489–1531), a Franciscan friar, shipwrecked on the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511 and captured and enslaved by Mayans.

- Giles, father of George Washington Carver.

- Glaumur, enslaved by the outlaw Grettir in early medieval Iceland (protagonist of "Grettis saga"). Glaumur is mentioned as loyally sharing Grettir 's long exile on the lonely island of Drangey, off the northern tip of Iceland, though in the circumstances described in the saga he could have easily escaped.

- Gosala, a sixth-century BC ascetic teacher of ancient India – a contemporary (and rival) of Gautama Buddha – was said to have been born into slavery, and became a naked ascetic after fleeing from his irate captor, who managed to grab hold of Gosala's garment and disrobe him as he fled.

- Gonzalo Guerrero (died 1536), a sailor from Palos, Spain, who shipwrecked along the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511 and was enslaved by the local Maya.

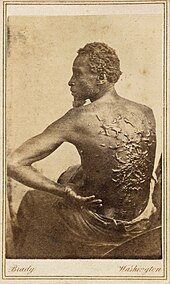

- Gordon, also known as Whipped Peter, an enslaved African-American man who escaped to a Union Army camp from a plantation near Baton Rouge, Louisiana in 1863. The images of Gordon's scourged back taken during a medical examination were published in Harper's Weekly and provided Northerners visual evidence of the brutality of slavery. They inspired many free blacks to enlist in the Union Army.[81]

- Gryphus Ancient Roman slave. The epigraph of the enslaved boy Iucundus describes him as the son of Gryphus and Vitalis.[82]

- Gülnuş Sultan (1642 – 6 November 1715) was Haseki Sultan of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV and Valide sultan to their sons Mustafa II and Ahmed III.

- Guðríður Símonardóttir (1598–1682), Icelandic woman taken captive by North African slavers (Barbary Pirates).

- Gustav Badin (died 1822), servant at the royal Swedish court, originally a Danish slave.

H

[edit]

- Hababah, concubine of Caliph Yazid II.

- Hagar, biblical figure, belonging to Sarah.

- Hanna, an enslaved woman in Virginia, and grandmother of Jackey Wright, who sued for her freedom in Hudgins v. Wright (1806) on the grounds that three generations descended from Butterwood Nan, who was an American Indian, not African. The Virginia Supreme Court affirmed a lower court decision by George Wythe, that because of Jackey's and Hanna's appearance as mixed Indian and European, she was entitled to the presumption of freedom, given the limited nature of Indian slavery. St. George Tucker and Spencer Roane said that, as most Africans had been imported as slaves and blacks descended from enslaved mothers, a black person would not have the same presumption of freedom.[83][84]

- Hannah Bond (born 1830s), pen name Hannah Crafts,[85] wrote The Bondwoman's Narrative after gaining her freedom. Possibly the first novel by an African-American woman, it is the only known novel written by a woman fugitive from slavery.

- Hark Olufs (1708–1754), Danish sailor, was captured by Algerian pirates. Sold to the Bey of Constantine, he became Commander in Chief of the Bey's cavalry. He was released in 1735.

- Harriet Hemings (1801–after 1822), daughter of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson.

- Harriet Jacobs (1813–1897), author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

- Harriet Powers (1837–1910), American folk artist, and quilter.

- Harriet Tubman (c. 1822 – 1913), nicknamed "Moses" because of her efforts in helping other American slaves escape through the Underground Railroad.

- Harry, the plaintiff in the 1818 Harry v. Decker & Hopkins decision by the Supreme Court of Mississippi (the first among U.S. southern states) to free a person from slavery solely on the basis of prior residence in a free territory.

- Harry Washington (died 1800), also known as Henry Washington, was enslaved by George Washington.[86] Transported as a slave to America, he was bought by Washington in 1763 to work on a project for draining the Great Dismal Swamp.[87]

- Hafsa Sultan (died March 1534) was the wife of Selim I and the first valid sultan of the Ottoman Empire as the mother of Suleiman the Magnificent. Her background is disputed but some historians hold that she was a slave.

- Helen Gloag (1750–1790), of Muthill, Perthshire, Scotland, became the Empress of Morocco as the harem slave of Morocco's sultan.[88]

- Henry Highland Garnet (1815–1882), born an African-American slave in Maryland, escaped slavery in 1824, and became an abolitionist and educator.[89]

- Hercules (born c. 1755), head cook enslaved by George Washington at Washington's plantation, Mount Vernon. He escaped and gained his freedom in 1797, but his wife Alice and his three children remained enslaved.

- Helvius Successus, freed slave, and father of Roman emperor Pertinax.

- Hermas, author of the text The Shepherd of Hermas and brother of Pope Pius I.

- Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, born in Cartagena, was enslaved at the age of 13 when the ship bearing him to Spain for education sank off Florida. A Calusa chief enslaved him and used him as a translator until he was ransomed at 30.[90]

- Horace King (1807–1885), American architect, engineer, and bridge builder, was born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation.

- Hümaşah Sultan (fl. 1647–1672) was the wife of Sultan Ibrahim of the Ottoman Empire.

- Hurrem Sultan (c. 1504 – 15 April 1558), also known as Roxelana, an Eastern European girl, was captured by slave traders and sold to the Imperial Harem, becoming the chief consort and legal wife of the Ottoman sultan Süleyman the Magnificent.

- Halime Sultan (c. 1570-after 1639) was Valide Sultan and de facto co-ruler of the Ottoman Empire

- Handan Sultan (c. 1568 – 9 November 1605) was Valide Sultan and de facto regent of the Ottoman Empire

I

[edit]

- İbrahim Pasha (c. 1495 – 1536), Suleiman the Magnificent's first appointed Grand Vizier. Greek by birth, at the age of six he was sold as a slave to the Ottoman palace for future sultans where he befriended Suleiman, who was the same age.

- Icelus Marcianus, a slave and later freedman of Roman emperor Galba in the 1st century CE. He was one of three men said to completely control the emperor, increasing Galba's unpopularity.[91]

- Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), prominent African-American activist, born into slavery, who in later life campaigned against and succeeded in abolishing lynching. In 1909 she co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

- Imma, a Northumbrian aristocrat who was knocked unconscious in battle and later pretended to have been a peasant, so that his captors would not kill him. His manners and bearing soon betrayed him, and he was sold into slavery.[92]

- Isabel de Solís (fl. 1485), enslaved Castilian concubine of Abu l-Hasan Ali, Sultan of Granada.[93]

- Isabella Gibbons (1826–1890), became a schoolteacher in Virginia after her liberation in 1865.

- Isfandíyár, an enslaved servant in Bahá'u'lláh's house in Tehran,[94] Isfandíyár died in Mazandaran[95][96]

- Israel Jefferson (c. 1800 – after 1873), known as Israel Gillette before 1844, was born into slavery at Monticello, the estate of Thomas Jefferson, and worked as a domestic servant close to Jefferson for years.

- Isthmias, a woman in ancient Greece described in Against Neaera as the property of Nicarete, who prostituted her.

- Iucundus, boy in Ancient Roman, described in his epitaph as the slave of Livia, the wife of Drusus Caesar, the son of Gryphus and Vitalis. It states he was seized and murdered by a witch, and warns parents to guard their children to prevent such a fate.[82]

- Ivan Bolotnikov (1565–1608), a fugitive kholop (enslaved in Russia) and leader of the Bolotnikov rebellion in 1606–1607.

- Ivan Argunov (1729–1802), Russian serf painter, one of the founders of the Russian school of portrait painting.

J

[edit]

- Jack Gladstone, leader of the Demerara rebellion of 1823.

- Jackey Wright, an enslaved American woman who sued for and won her freedom in the famous 1806 Virginia case of Hudgins v. Wright. The opinion of the Virginia Supreme Court relied on Wright appearing white and Native American, whereas the lower court under George Wythe had tried to establish a presumption of freedom for all people, regardless of race.

- James Armistead Lafayette (1760–1830), an enslaved African-American man who served the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War as a double agent.

- James Baugh, an enslaved American who sued for his freedom on the grounds that his maternal grandmother had been an Indian.[97]

- James Hemings (1765–1801), mixed-race American man enslaved and later freed by Thomas Jefferson. He was the older brother of Sally Hemings and a half-sibling of Jefferson's wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson, through their father John Wayles.

- James Leander Cathcart (1767–1843), a diplomat and sailor notable for his narrative of eleven years of enslavement in Algiers and for his diplomatic accomplishments while in slavery.

- James Poovey (born c. 1769), a Philadelphian who was enslaved from birth and achieved manumission through non-violent disobedience.

- James M. Priest (1819–1883), 6th Vice President of Liberia, born into slavery in Kentucky

- James Somersett or Somerset, a man enslaved in colonial America whose escape while in England in 1771, supported by notable British abolitionists, led to the milestone legal case Somerset v Stewart, which effectively ended slavery in Britain, though not in its colonies.

- James W. C. Pennington (c. 1807–1870), African-American writer and abolitionist.[98]

- Jan Ernst Matzeliger (1852–1889), a Surinamese-American inventor in shoe manufacturing.

- Jane Johnson (1814 or 1827 – 1872), gained freedom on July 18, 1855 with her two young sons while in Philadelphia with her owner and his family. She was aided by William Still and Passmore Williamson, abolitionists of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and its Vigilance Committee.

- Jean Amilcar (c. 1781–1793), the Senegalese foster son of Marie Antoinette.

- Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758–1806), leader of the Haitian Revolution and first leader of independent Haiti.

- Jean Marteilhe (1684–1777), French Huguenot slave narrator, he served as a galley slave.

- Jean Saint Malo (died 1784), leader of runaway slaves (maroon colony) in Spanish Louisiana and namesake of Saint Malo, Louisiana.

- Jean Parisot de Valette (1495–1568), a knight of the Order of Saint John was captured and made a galley slave in 1541 by Barbary pirates under the command of Turgut Reis. He was freed after about a year and later became Grandmaster of the Order.

- Jeffrey Hudson (1619–c. 1682), an English courtier who spent 25 years enslaved in North Africa.

- Jehu Grant (c. 1752–1840), Revolutionary War veteran.

- Jermain Wesley Loguen (1813–1872), an African-American man who escaped slavery and became an abolitionist, a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and the author of a slave narrative.

- Jerry – see William Henry

- Jim Cuff or Jim Crow was a physically disabled enslaved African man, variously claimed to have resided in St. Louis, Cincinnati, or Pittsburgh,[99][100] whose song and dance supposedly inspired the blackface song and dance "Jump Jim Crow" by white comedian Thomas D. Rice. The great popularity of Rice's creation soon led to Jim Crow becoming a pejorative name for blacks, and later to the name being used for the segregationist Jim Crow Laws, a mockery of the namesake.

- Jim Henson, an African man who escaped slavery and published his memoirs, Broken Shackles, in Canada.

- Joana da Gama (c. 1520–1586), a Portuguese maid-of-honor and writer.

- Joe, a man enslaved by William B. Travis, one of the Texian commanders in the Battle of Alamo. After the Texian defeat, Mexican General Santa Anna spared Joe, hoping to convince other slaves in Texas to support the Mexican government over the Texian rebellion.[101] Afterwards, Joe together with some other survivors were sent to Gonzales and encouraged to relate the events of the battle, and to inform the remainder of the Texian forces that Santa Anna's army was unbeatable.

- John Axouch (1087–1150), a Seljuk Turk captured as a child by the Byzantine Empire, freed and raised in the imperial household as the companion of future emperor John II Komnenos, and on his accession given command of the empire's armies and remaining the emperor's only close personal friend and confidant.

- John "Lit" Fleming, born into slavery in Virginia but later moved to Edmundson, Arkansas, with his parents and siblings. He would then move to Memphis, Tennessee, and was part-owner of the newspaper Memphis Free Speech with activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

- John Munroe Brazealle, along with his mother, the subjects of Hinds v. Brazealle (1838), a case in the Supreme Court of Mississippi which denied the legality and inheritance rights in Mississippi of deeds of manumission executed by Elisha Brazealle, a Mississippi resident, in Ohio to free the pair.

- John Brown (c. 1810–1876), escaped and wrote of conditions in the Deep South of the United States.

- John Casor, the first to be enslaved as the result of a civil case in the Thirteen Colonies (Virginia Colony, 1655).

- John Ezzidio (c. 1810–1872), enslaved Nigerian man who became a successful Sierra Leonese politician and businessman.

- John Jea (born 1773), enslaved African-American man best known for his 1811 autobiography, The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, the African Preacher.

- John Joyce born into slavery in Maryland, served in the United States Navy, held a variety of jobs after, and murdered a shopkeeper, Sarah Cross; his life and crime recounted in the murder literature of his day.[102]

- John R. Jewitt (1783–1821), an English armourer who spent three years as a captive of Maquinna of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people on the Pacific coast of what is now Canada.

- John Punch (fl. 1630s, living 1640), an enslaved African man in the Virginia Colony in the 17th century.[103][104] In July 1640, the Virginia Governor's Council sentenced him to serve for the remainder of his life as punishment for running away to Maryland. Many historians consider Punch the "first official slave in the English colonies,"[105] and his case as the "first legal sanctioning of lifelong slavery in the Chesapeake."[103] Historians also consider this to be one of the first legal distinctions between Europeans and Africans made in the colony,[106] and a key milestone in the development of the institution of slavery in the United States.[107]

- John S. Jacobs (1815–1873), born into slavery in North Carolina, escaped, became an abolitionist speaker and author of a slave memoir. Brother of famed author Harriet Jacobs.

- John Smith (1580–1631), English soldier, sailor, and author best known for his role in the survival of the Jamestown colony in Virginia. Smith was captured by the Crimean Tatars in 1602 while fighting in Wallachia and enslaved by the Ottoman Empire, but escaped and returned to England by 1604. As Smith described it: "we all sold for slaves, like beasts in a market-place."[108]

- Jordan Anderson (1825–1907), best known for a letter sent to his former oppressor/master in response to the latter's request that Jordan return to his service.

- Jordan Winston Early (1814 – after 1894) was an American Methodist multiracial preacher who was the subject of a book about his life as a slave.

- John White, an enslaved black boy who was captured by Creeks in 1797 and escaped back to New Orleans, where he was returned to slavery by Spanish officials.[109]

- John Ystumllyn, also known as Jac Du or Jack Black, an 18th-century Welsh gardener and the first well-recorded Black person of North Wales.[110][111]

- Jonathan Strong, the subject of one of the earliest legal cases relating to slavery in Britain.[112][113][114]

- José Antonio Aponte leader of the Aponte conspiracy.

- Joseph, important figure in the Old Testament and the Quran.

- Joseph Antonio Emidy (1775–1835), violinist and composer born in Africa, died in Cornwall.

- Joseph Cinqué (1814–1879), also known as Sengbe Pieh, leader of a slave rebellion on the slave ship La Amistad and defendant in the subsequent Supreme Court case United States v. Amistad in 1839.

- Joseph Jackson Fuller (1825–1908), one of the earliest slaves to be freed in Jamaica, initially under the partial freedoms of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

- Joseph Knight, successfully sought his freedom through a legal suit in Scotland in 1777, a case which established that Scots law would not uphold the institution of slavery.

- Josephine Bakhita (c. 1869–1947), Sudanese-born Roman Catholic Canossian nun and saint.

- Joshua Glover, fugitive from slavery aided by abolitionists at Racine, Wisconsin in 1854.

- Juan Francisco Manzano (c. 1797–1854), Cuban poet.[115]

- Juan Gros, a free black soldier captured near Pensacola by an Upper Creek, who sold him to a white trader who sold him to Mitasuki chief Kinache, from whom Spaniards ransomed him.[116]

- Juan Latino, called "el negro Juan Latino", from Ethiopia, brought to Spain as a child, received an education and rose to be professor of Latin at the University of Granada, in 16th-century Spain.

- Juan Ortiz, a young Andalusian nobleman enslaved by Chief Ucita in Florida to avenge injuries he suffered at the hands of the expedition Ortiz belonged to.[117]

- Juan Valiente (d. 1553), black African slave on permission to be a conquistador. He died at the battle of Tucapel against Mapuche forces in Chile.[118]

- Julia Chinn, an octoroon enslaved woman and common-law wife of Richard Mentor Johnson, ninth Vice President of the United States.

- Julia Frances Lewis, mother of Amanda American Dickson by the son of her owner.[119]

- Juliana, a Guaraní woman from present-day Paraguay, famous for killing her Spanish enslaver between 1538 and 1542 and urging other indigenous women to do the same.[120][121]

- Julius Soubise (1754 – 25 August 1798) was a freed Afro-Caribbean slave who became a well-known fop in late eighteenth-century Britain.

- Julius Zoilos, enslaved by Julius Caesar. After obtaining his freedom, he rose to prominence in his home city of Aphrodisias after Caesar's death.[122]

- Jupiter Hammon (1711–before 1806), in 1761 became the first African-American writer to be published in the present-day United States. Born into slavery, Hammon was never emancipated. He is considered one of the founders of African-American literature.

K

[edit]

- King Jaja of Opobo (1821–1891), sold at about the age of 12 into slavery in the Kingdom of Bonny in present-day Nigeria. Proving at an early age his aptitude for business, he not only earned his way out of slavery but also became a rich and powerful merchant prince and the founder of the Opobo city-state, his career eventually ended by the British colonizers whom he tried to defy.

- Anna Kingsley (1793–1870), enslaved woman and then a planter and slave owner herself.

- Kunta Kinte (c. 1750 – c. 1822), a character from the 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family whom author Alex Haley was based on one of his actual ancestors. Kinte was a man of the Mandinka people who grew up in a small village called Juffure in what is now The Gambia and was raised as a Muslim before being captured and enslaved in Virginia.[123] The historical accuracy of Haley's story is disputed.[124]

- Kodjo (c. 1803–1833), a Surinamese slave who was burnt alive for starting the 1832 fire in Paramaribo, Dutch Suriname, possibly as an act of resistance.

- Kösem Sultan (1589–1651), an Ottoman enslaved woman, later extremely powerful as wife, then mother and later grandmother of the Ottoman sultan during the 130-year period known as the Sultanate of Women.

L

[edit]

- Lalla Balqis (1670 – after 1721), an Englishwoman captured and enslaved by Corsairs and included in the harem of the Sultan of Morocco.

- Lamhatty, a Tawasa Indian captured and enslaved by Creek; he escaped.[125]

- Lampegia (died after 730), Aquitanian noblewoman, captured by Abd al-Rahman ibn Abd Allah al-Ghafiqi, who in 730 took the Llivia Fortress, executed her spouse Munuza and sent her as a slave to the harem of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in Damascus.[126]

- La Mulâtresse Solitude (1772–1802), a slave on the island of Guadeloupe freed in 1794 by the abolition of slavery during the French Revolution. She was executed after having fought for freedom when slavery was reintroduced by Napoleon in 1802.

- Laurens de Graaf (c. 1653–1704), a Dutch pirate, mercenary, and naval officer, enslaved by Spanish slave traders when captured in what is now the Netherlands and transported to the Canary Islands to work on a plantation, prior to 1674.

- Lear Green (c. 1839—1860), an African-American woman from Maryland who escaped to freedom in New York by mailing herself in a box.

- Leo Africanus, (1494–1554), a Moor born in Granada who was taken by his family in 1498 to Morocco when expelled from Spain. As an adult he served on diplomatic missions. Captured by Crusaders while in the Middle East, he was enslaved in Rome and forced to convert to Christianity. He eventually regained his freedom and lived out his life in Tunis.

- Leofgifu the dairy maid, an enslaved woman in Anglo-Saxon England, named in her manumission.[127]

- Leoflaed, an enslaved woman in Anglo-Saxon England, whose freedom was bought by a man who described her as a "kinswoman."[128]

- Leonor de Mendoza, an enslaved woman in colonial Mexico who tried to marry Tomás Ortega, a man enslaved by another master; when her master imprisoned Tomás she appealed to a church court for assistance, which threatened excommunication if he did not free Tomás.[129]

- Letitia Munson (c. 1820 – after 1882), midwife and formerly enslaved, she was acquitted of performing an illegal abortion in Canada.

- Lewis Adams (1842–1905), a formerly-enslaved man who co-founded the Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University, in Alabama.

- Lewis Hayden (1811–1889), African-American man born in Kentucky, later elected to the Massachusetts General Court.[130]

- Lilliam Williams, a Tennessee settler who was captured by the Creek while pregnant. The Creek adopted her daughter (whom she named Molly and they named Esnahatchee,); they kept the girl when Williams' freedom was arranged.[131]

- Liol, a Chinese man enslaved by Mongol bannerman Soosar. He was rewarded with semi-independent status, as a separate register dependent. In 1735, his son Fuji tried to claim that he and his brother were in fact Manchus and detached household bannermen, but failed.[132]

- Lott Cary (c. 1780 – November 10, 1828), born an African-American slave in Virginia, bought his freedom c. 1813, emigrated to Liberia in 1822, where he later served as colonial administrator.[133]

- Louis Hughes (1832–1913), African-American man who escaped slavery, author, and businessman[134]

- Lovisa von Burghausen (1698–1733), Swedish writer who published an account of being enslaved in Russia after being taken prisoner during the Great Northern War.

- Lucius Agermus, freedman of Agrippina the Elder.[135]

- Lucius Aurelius Hermia, a freedman butcher whose tombstone glorifies his marriage with his fellow freedwoman Aurelia Philematium.[136]

- Lucius Cancrius Primigenius, a freedman of Clemens in an inscription praising him for breaking spells against the city.[137]

- Lucius of Campione, who lost a lawsuit in the 8th century over a man Toto's claimed ownership of him.[138]

- Lucy, the black woman enslaved by John Lang. She was taken captive by the Creek when 12 years old and kept in slavery in Creek territory, where she had slave children and grandchildren.[139]

- Lucy Ann (Berry) Delaney (1830–1891), formerly-enslaved woman, daughter of Polly Berry.

- Lucy Higgs Nichols (1838–1915), escaped slavery, served as a nurse in the Civil War, member of the Grand Army of the Republic.

- Luís Gama (1830–1882), born free in Brazil, illegally sold into slavery as a child, he regained liberty as an adult and became a lawyer who freed hundreds from slavery without asking for recompense, notably in the Netto Case.

- Lunsford Lane (1803 – after 1870), an enslaved African-American man and entrepreneur from North Carolina who bought freedom for himself and his family. He also wrote a slave narrative.

- Lyde, an enslaved woman freed by Roman empress Livia.[140]

- Lydia, an enslaved woman who was shot and wounded by her captor when she struggled to escape a whipping. The action was ruled legal by the Supreme Court of North Carolina in 1830 (see North Carolina v. Mann).

- Lydia Carter, the "Little Osage Captive," captured and enslaved among the Cherokee. She was ransomed by Lydia Carter, who made her her namesake. The Osage attempted to reclaim her, but she took ill and died.[141]

- Lydia Polite, mother of Robert Smalls.

M

[edit]

- Madison Hemings (1805–1877), son of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson.

- Mae Louise Miller (1943–2014), American woman kept in modern-day slavery (peonage) until 1961.

- Malgarida (born c. 1488), black African woman and companion of the conquistador Diego de Almagro. In 1536 she became the first non-indigenous woman to enter the territory of what is now Chile.[142]

- Malik Ambar, born in 1548 as Chapu, a birth-name in Harar, Adal Sultanate in Somalia. He was from the now extinct Maya ethnic group. As a child he was sold in slavery by his parents[143] Mir Qasim Al Baghdadi, one of his slave owners, eventually converted Chapu to Islam and gave him the name Ambar, after recognizing his superior intellectual qualities.[144][145] Malik was brought to India as a slave. While in India he created a mercenary force numbering up to 1500 men. It was based in the Deccan region and was hired by local kings. Malik became a popular Prime Minister of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, showing administrative acumen. He is also regarded as a pioneer in guerilla warfare in the region. He is credited with carrying out a revenue settlement of much of the Deccan, which formed the basis for subsequent settlements. He is a figure of veneration to the Siddis of Gujarat. He humbled the might of the Mughals and Adil Shah of Bijapur and raised the low status of the Nizam Shah.[146][147]

- La Malinche (c. 1496 or c. 1501 – c. 1529), a Nahua woman given as a slave to Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. She became his personal interpreter, advisor, and mistress during the Spanish conquest of Mexico.

- Mammy Lou (1804 – after 1918), a formerly-enslaved woman who lived to extreme old age and acted in the 1918 silent film The Glorious Adventure.

- Manes, a man enslaved by Diogenes of Sinope. He ran away shortly after his owner arrived in Athens, and Diogenes failed to pursue him on the grounds that if Manes could live without him, it would be disgraceful if he could not equally live without Manes.

- Manjeok, enslaved Korean person and leader of an abortive slave uprising.

- Manjutakin (died 1007), a Turkish-born enslaved soldier (ghulam) and general of the Fatimids.

- Mann, either of two men enslaved by Æthelgifu in Anglo-Saxon England and freed by the terms of her will. One was a goldsmith and the other's wife was freed at the same time.[65]

- Marcos Xiorro, a man enslaved in Puerto Rico who, in 1821, planned a revolt against the sugar plantation owners and the Spanish colonial government. Though the conspiracy was unsuccessful, he became a part of island's folklore.[148]

- Marcia, mistress of Roman emperor Commodus.

- Marcius Agrippa (late 2nd and early 3rd century), an enslaved man who was not only freed but eventually elevated to senatorial rank by Roman emperor Macrinus.

- Marcus Tullius Tiro (c. 103 – 4 BCE), Roman author, slave, and secretary of the Roman politician Cicero, later freed. He invented a long-lasting system of shorthand and wrote books that are now lost.

- Margaret Garner (1835–1858), an enslaved woman in antebellum America infamous for killing her own daughter rather than see the child returned to slavery.

- Margaret Himfi (before 1380 – after 1408), a Hungarian noblewoman who was abducted and enslaved by Ottoman marauders in the late 14th century. She later became an enslaved mistress of a wealthy Venetian citizen of Crete, with whom she had two daughters. Margaret returned to Hungary in 1405.

- Marguerite Duplessis (c. 1718 – after 1740), a Pawnee woman enslaved in Montreal who, in 1740, unsuccessfully sued for her freedom.

- Maria ter Meetelen (1704 – fl. 1751), Dutch writer of a slave narrative, enslaved by pirates and sold to the Sultan of Morocco. Her 1748 biography is considered to be a valuable witness statement of the life of a former slave.

- Marie (died 1759), an enslaved Cree woman sentenced to death in Trois-Rivières, New France.

- Margaret Morgan, involved in the Prigg v. Pennsylvania United States Supreme Court case in which the court held that the federal Fugitive Slave Act precluded a Pennsylvania state law that prohibited blacks from being taken out of Pennsylvania into slavery, and overturned the conviction of Edward Prigg as a result.

- Marguerite Scypion (c. 1770s – after 1836), an African-Natchez woman born into slavery in St. Louis who sued for and eventually won her freedom.

- Maria al-Qibtiyya (died 637), also known as "Maria the Copt" (Arabic: مارية القبطية) or, alternatively, Maria Qupthiya, an enslaved Copt who was sent as a gift from Muqawqis, a Byzantine official, to the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 628, and became Muhammad's concubine.[149] She was the mother of Muhammad's son Ibrahim, who died in infancy. Her sister, Sirin, was also sent to Muhammad. Muhammad gave her to his follower Hassan ibn Thabit. Maria died five years after Muhammad's death in 632.

- Maria, (died 1716), the leader of a slave rebellion on Curaçao.

- Maria Perkins, an enslaved woman from Virginia who wrote a letter to her husband in 1852 about their son being sold away.[150]

- Mariah Bell Winder McGavock Otey Reddick (died 1922), as a girl she was given as a wedding gift to Carrie Winder when she married John McGavock in 1848 in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. Mariah, born enslaved in Mississippi, was taken to Franklin, Tennessee, where she lived for most of the remainder of her life. She was matched with Harvey Otey after his first wife Phebe died. They had several children, including two sets of twins, born into slavery. During the Civil War, she was sent to Montgomery to be far from Union lines and possible freedom. She has been featured in three novels: Widow of the South and Orphan Mother both by Robert Hicks and in a book by her great-grandson William 'Damani' Keene and his wife Carole 'Ife' Keene entitled Clandestine: The Times and Secret Life of Mariah Otey Reddick.[151]

- Marianna Malińska (died after 1797), Polish serf and Royal Ballet Dancer, donated to the king of Poland by will and testament.[152]

- Marie-Cessette Dumas, a woman enslaved by Marquis Antoine de la Pailleterie, mother of General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, and grandmother of famous author Alexandre Dumas, père.

- Marie-Josèphe dite Angélique (died 1734), a black Portuguese enslaved woman who was tried and convicted, beaten and hanged for setting fire to her female owner's home, burning much of what is now referred to as Old Montreal.

- Marie Thérèse Metoyer, a planter, and businesswoman at the colonial Louisiana outpost of Natchitoches after being freed.

- Mark, Massachusetts man enslaved by Captain John Codman.[153] Mark's body was displayed in chains publicly near Charlestown, Massachusetts for twenty years. The gruesome display of his body was so well known at the time, the site where Mark's body was displayed is mentioned by Paul Revere as a landmark, in his 1798 account of Revere's 1775 midnight ride.[154]

- Martha Ann Erskine Ricks (1817–1901), an African-American born enslaved in Tennessee, later an Americo-Liberian quilter[155]

- Marthe Franceschini (1755–1799), an Italian captured and enslaved by Corsairs and included in the harem of the Sultan of Morocco.

- Mary, mother of George Washington Carver.

- Mary (died 1838), teenager hanged for the murder of Vienna Brinker, a two-year-old girl she was babysitting

- Mary Black, one of three enslaved women charged with witchcraft during the Salem witch trials of 1692.

- Mary Calhoun, white woman and cousin of John C. Calhoun who was kidnapped by Cherokee. She never returned home.[1]

- Mary Edmonson (1832–1853), along with her sister Emily, joined an unsuccessful 1848 escape attempt known as the Pearl incident, but Henry Ward Beecher and his church raised the funds to free them.

- Mary Eliza Smith, described in various records as "slave" or "former slave," common-law wife of Michael Morris Healy and mother of his children, including James Augustine Healy, Patrick Francis Healy, Michael A. Healy, and Eliza Healy.

- Mary Fields (c. 1832–1914): the first African-American female star route mail carrier in the United States.

- Mary Mildred Williams, Nee Botts (born 1847), the original 'Poster Child' whose image was used to advance the abolitionist cause by propagandising 'White Slavery' in 1855.

- Mary Prince (c. 1788 – after 1833), the account of her life galvanized the anti-slavery movement in England.

- The Master of Morton and the eldest son of the Chief of Clan Oliphant, two Scottish nobles who were exiled from Scotland after being implicated in the 1582 Raid of Ruthven. The ship in which they sailed was lost at sea, and it was rumoured that they had been caught by a Dutch ship. The last report was that they were slaves on a Turkish ship in the Mediterranean. A plaque to their memory was raised in the church in Algiers.

- Masúd, initially purchased as a youth by Khál-i Akbar, an uncle of the Báb, Masúd would serve Bahá'u'lláh in Acre.[156]

- Matilda McCrear (c. 1857 – 1940), the last surviving victim in the United States of the Transatlantic slave trade. Transported upon the slave ship Clotilda.

- Mende Nazer (born c. 1982), a Nuba woman captured in Darfur and transported from Sudan to London, where she eventually won refugee status and wrote the memoir Slave: My True Story (2002).

- Menecrates of Tralles a Greek physician during the 1st century BC.

- Hans Mergest, a participant in the Crusade of Varna who was captured by the Ottomans in the Battle of Varna (1444) and spent 16 years in captivity. He was the protagonist of a song by minnesinger Michael Beheim.

- Metaneira, a woman in ancient Greece described in Against Neaera as the property of Nicarete, who prostituted her.

- Shadrach Minkins (1814–1875), a fugitive from slavery saved by abolitionists at Boston in 1850.

- Michael Shiner (1805–1880), enslaved laborer, painter entrepreneur, civic leader and diarist at the Washington Navy Yard.

- Miguel de Buría (c. 1510 – c. 1555), slave and rebel.[157]

- Miguel Perez was the Spanish name of a boy of the Yojuane people who was among 149 Yojuane women and children taken captive in 1759 during an attack on their camp by an expedition of Spaniards and Apaches along the Red River in what is now northern Texas.[158] Many of the captives died of smallpox while those who survived were enslaved.[159] The boy was sold to a Spanish soldier who bestowed the Spanish name on him. Perez became an Hispanicized Indian of San Antonio but he continued to maintain contact with the Yojuanes. In 1786, Perez was recruited to convince the Yojuanes and their Tonkawa allies to go to war with the Lipan Apache, which he did successfully.[158]

- Mikhail Matinsky (1750–1820), Russian serf scientist, dramatist, librettist and opera composer.

- Michał Rymiński (died after 1797), Polish serf and Royal Ballet Dancer, donated to the king of Poland by will and testament.[160]

- Mikhail Shchepkin (1788–1863), Russian serf actor.

- Mikhail Shibanov, Russian serf painter active during the 1780s.

- Mikhail Tikhanov (1789–1862), Russian serf artist.

- Mina Kolokolnikov (1708?–1775?), Russian serf painter and teacher.

- Mingo, the 15–16 years old boy enslaved by the Titsworth family in Tennessee, who was captured in 1794 by Creeks in a raid on the house and kept as a slave by them.[161][162]

- Minerva (Anderson) Breedlove, mother of Madam C.J. Walker.

- Moses A. Hopkins (1846–1886), African-American diplomat, U.S. minister to Liberia.[163]

- Hájí Mubárak, purchased at the age of 5 years old by Hájí Mírzá Abú'l-Qásím, the great-grandfather of Shoghi Effendi and brother-in-law of the Báb, Hájí Mubárak was sold to the Báb in 1842 at the age of 19 for fourteen tomans.[164] Hájí Mubárak died at about the age of 40 and is buried in the grounds of the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, Iraq.

- Mustapha Khaznadar (1817–1878), born Georgios Kalkias Stravelakis, a Christian Greek on the island of Chios, captured by Ottoman troops during the 1822 Massacre of Chios, converted to Islam and given the name Mustapha, sold in Constantinople to an envoy of the Husainid Dynasty. He was raised by the family of Mustapha Bey, then by his son Ahmad I Bey[165] while he was still crown prince. Initially, he worked as the prince's private treasurer before becoming Ahmad's state treasurer (khaznadar).[165] He managed to climb to the highest offices of the Tunisian state, married Princess Lalla Kalthoum in 1839 and was promoted to lieutenant-general of the army, made bey in 1840 and then president of the Grand Council from 1862 to 1878.

- Muyahid ibn Yusuf ibn Ali, 11th-century leader of the Saqaliba (slaves of supposed Slavic origin) in Dénia, Spain (then part of Muslim Al Andalus). Taking advantage of the crumbling of the Caliphate of Córdoba, he and his followers rebelled, freed themselves, seized control of the city and established the Taifa of Dénia, a city-state which at its peak extended its reach as far as the island of Majorca.

N

[edit]- Nafisa al-Bayda, Egyptian investor and diplomat, referred to as a "white slave", originally bought as a slave concubine.

- Nancy, otherwise called Ann, the plaintiff in the 1799 New Brunswick habeas corpus suit R v Jones