Oslo Metro

| Oslo Metro | |

|---|---|

| |

MX3000 on the Furuset Line | |

| Overview | |

| Native name | T-banen i Oslo |

| Owner | Sporveien (main owner) Ruter (administration, management and ticketing) Oslo Vognselskap (rolling stock) |

| Locale | Oslo, Bærum, Norway |

| Transit type | Rapid transit |

| Number of lines | 5 in operation 1 under construction |

| Number of stations | 101 |

| Daily ridership | 323,000 (2016) |

| Annual ridership | 118,000,000 (2016)[1] |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | 31 May 1898 as suburban tram 28 June 1928 as underground tram 22 May 1966 as T-bane |

| Operator(s) | Sporveien T-banen |

| Rolling stock | 115 × 3-car MX3000 |

| Technical | |

| System length | 85 km (53 mi)[2] |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | 750 V DC third rail |

The Oslo Metro (Norwegian: Oslo T-bane or Oslo Tunnelbane or simply T-banen) is the rapid transit system of Oslo, Norway, operated by Sporveien T-banen on contract from the transit authority Ruter. The network consists of five lines that all run through the city centre, with a total length of 85 kilometres (53 mi),[2] serving 101 stations of which 17 are underground or indoors. In addition to serving 14 out of the 15 boroughs of Oslo, two lines run to Kolsås and Østerås, in the neighbouring municipality of Bærum. In 2016, the system had an annual ridership of 118 million.[1]

The first rapid transit line, the Holmenkollen Line, opened in 1898, with the branch Røa Line opening in 1912. It became the first Nordic underground rapid transit system in 1928, when the underground line to Nationaltheatret was opened. After 1993 trains ran under the city between the eastern and western networks in the Common Tunnel, followed by the 2006 opening of the Ring Line. All the trains are operated with MX3000 stock. These replaced the older T1000 stock between 2006 and 2010.

History

[edit]

Suburban lines in the west

[edit]Rail transport in Oslo started in 1854, with the opening of Hoved Line to Eidsvoll, through Groruddalen. In 1872, Drammen Line, going through Oslo West, and in 1879, Østfold Line going through Nordstrand opened, offering a limited rail service to those parts of the city.[3] By 1875, Kristiania Sporveisselskab (KSS) opened the first horsecar trams.[4] In 1894 electric trams were in service by Kristiania Elektriske Sporvei (KES).[5]

The first suburban tram line was the Holmenkollen Line that was opened by Holmenkolbanen in 1898; like all the later suburban tram line these were electric trams with a grade-separated right-of-way and proper stations instead of tram stops, making it the first rapid transit in Oslo. Unlike the other suburban tram lines that were built later, the Holmenkollen Line was not extended into the city as a streetcar—instead passengers had to change at Majorstuen to the streetcars, though the system did not take into use wider suburban stock (3.1 metres (10 ft 2 in)) until 1909.[6] A branch line was opened in 1912, to Smestad,[7] and in 1916 the Holmenkollen Line was extended to Tryvann, with the last part from Frognerseteren single track and used for freight,[8] and removed in 1939.[9]

In 1912, the construction of the first underground railway in the Nordic Countries started, when A/S Holmenkolbanen started construction of an extension of their line from Majorstuen to Nationaltheatret. The 2.0 kilometres (1.2 mi) line was opened in 1928, with one intermediate station at Valkyrie Plass, giving the two suburban lines access to the central business district of Oslo.[10] In retrospect, it is seen as een early premetro example.[11] It was the second underground railway to be opened in the Nordic countries after Boulevardtunnlen in Copenhagen which opened in July 1918.[12]

The success of the suburban lines tempted KES to extend their streetcar service west from Skøyen as a suburban line; the Lilleaker Line opened to Lilleaker in 1919, to Avløs in 1924 and to Kolsås in 1930. A new section from Jar to Sørbyhaugen opened in 1942, connecting the line from Jar to Kolsås to Nationaltheatret, and making it a rapid transit and the replacement of stock with wide suburban standard.[13][14] This service remained part of the municipal Oslo Sporveier, that had bought all the streetcar companies in 1924.[15]

Compensation for large amounts of damage to houses along the route during construction, along with higher construction costs than calculated was a heavy burden on the company, and in 1934, the municipality of Aker took over the common stock, though the preferred stock remained listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange until 1975, as Oslo Sporveier gradually took over the operation of the western suburban lines. Akersbanerne opened the connecting Sognsvann Line in 1934.[10]

Metro

[edit]

The first idea to launch a citywide rapid transit was launched in 1912 with the construction of the Ekeberg Line; constructed with the same width profile as the Holmenkollen Line, the plan was to build a tunnel under the city center and run through trains, but large cost expenditures on the first section of the Common Tunnel ceased the plans. As part of the rebuilding after World War II a planning office for a T-bane was established in 1949, with the first plans launched in 1951; in 1954, the city council decided to build the T-bane network in Eastern Oslo with four branches. The system would feature improvements over the suburban lines in having a third rail power supply, cab signaling with Automatic Train Protection, stations long enough for six-car trains and level crossings replaced by bridges and underpasses—specifications christened metro standard.[16]

At the time there were two suburban tramways on the east side, the Ekeberg Line (opened in 1919)[5] and the Østensjø Line (1923).[17] Only the latter would be connected to the T-bane; the Ekeberg Line would remain a tramway, but three new lines were to be built—the Grorud Line on the north side and the Furuset Line on the south side of Groruddalen and the Lambertseter Line on the east of Nordstrand. These areas were all chosen as new suburbs for Oslo, and would quickly need a good public transport system; suburban lines would first be built out extending from the existing tramway, and later a final section with tunnel to the central station would be built. The Lambertseter Line was opened in 1957, from Brynseng to Bergkrystallen while the Østensjø Line was extended to Bøler in 1958.[16]

The metro opened on 22 May 1966, when the Common Tunnel opened from Brynseng to the new downtown station of Jernbanetorget, located beside the Oslo East Railway Station. In October the Grorud Line opened to Grorud while the Østensjø Line was connected to the system in 1967 when the line also was extended to Skullerud. In 1970, the Furuset Line opened to Haugerud and extended to Trosterud in 1974, at the same time as the Grorud Line was extended to Vestli. By 1981, the Furuset Line had reached Ellingsrudåsen.[18] The metro took delivery of T1000 rolling stock from Strømmens Værksted; from 1964 to 1978, 162 cars in three-car configurations were delivered for the eastern network.

One tunnel

[edit]

The eastern network was extended from Jernbanetorget to Sentrum in 1977. This station was forced to close in 1983, due to water leakage, and when it opened again in 1987, renamed Stortinget, the west network tunnel had also been extended there. Through services were not possible at the time because of incompatibility of signaling and power equipment. Not until 1993 did the first trains run through the station, after the Sognsvann Line had been rebuilt to "metro standard"; the Røa Line followed in 1995.[19] The Holmenkollen and Kolsås Lines remained non-metro, using dual mode trains that switch to overhead lines at Frøen and Montebello.[20] The western network took delivery of 33 T1300 cars in 1978–81, with an additional 16 converted from T1000. In 1994 twelve T2000 cars were delivered for the Holmenkollen Line.[21]

In 2003 the Ring Line opened, connecting Ullevål stadion to Storo.[14] The following year, construction work caused a tunnel to collapse on the Grorud Line—the system's busiest—forcing a shutdown of the line until December, and creating a havoc of overcrowded replacement buses.[22] In 2006 the ring was completed, to Carl Berners plass.[14] At the same time the Kolsås Line was closed for upgrade to metro standard.[14] In 2003 the section of the Kolsås Line in Bærum closed due to budget disagreements between the two counties; after a year of unpopular replacement buses, the line was reopened, only to close again in 2006 for upgrade to metro standard. Disagreements between the two counties meant the upgrade would be done separately on the two sides of the municipal boundary, with the Oslo side opening first.[23] In 2006 the replacement of existing rolling stock with new MX3000 units commenced.[24] The history of the metro and public transport in Oslo is celebrated at the Oslo Tramway Museum in Majorstuen.[25]

Network

[edit]

The current route network was introduced on 3 April 2016, with the opening of the connection tunnel from Økern to Sinsen and the new Løren station.

The Oslo Metro operates in all fifteen boroughs of Oslo, as well as reaching a bit inside the neighbouring municipality of Bærum. There are five lines, numbered 1 to 5, each colour-coded. They all pass through the Common Tunnel, serving eight branch lines. In addition two lines operate to the Ring Line. Two branches are served by two lines each: the Grorud branch is served by both lines 4 and 5, while the Lambertseter branch has full-time service by line 4 and limited service by line 1.[26]

The Grorud and Furuset Line head northeast into Groruddalen, while the other two eastern branches head south into Nordstrand. On the west side, the Holmenkoll and Sognsvann Line cover the northern boroughs of Oslo, along with the Ring Line that connects the northeastern and northwestern parts of town. The Kolsås and Røa Line reach deep into the neighbouring municipality of Bærum.[14] All the lines run through the Common Tunnel before reaching out to different lines, or into the Ring. All lines have a base service of four trains per hour while line 2 and the eastern section of line 3 have eight trains per hour weekdays 07:00–19:00. The eastern section of line 2 also has eight trains per hour Saturdays 10:00–19:00. A reduced half-hourly service operates on all lines during early weekend mornings. Trains run from about 05:00 (06:00 at weekends) to 01:00 the next morning.[26]

Lines

[edit]Line 1

[edit]Line 2

[edit]| Line 2: Østerås – Stortinget – Ellingsrudåsen | |

|---|---|

Line 3

[edit]| Line 3: Kolsås – Stortinget – Mortensrud |

|---|

Line 4

[edit]Line 5

[edit]Line 6 (under construction)

[edit]| Line 6: Majorstuen-Skøyen-Lysaker-Fornebu |

|---|

A new metro line that will extend from Majorstuen to Fornebu is under construction as of December 2020, aiming to be completed in 2027.[27]

An agreement has been reached and signed between the Oslo city government and the Norwegian state that would share the cost of 13 billion NOK equally between the city and the national government.[28]

Line 7 (proposed)

[edit]| Line 7: Majorstuen-Bislett-Grunerløkka-Tøyen-Helsfyr-Bryn |

|---|

Stations

[edit]

The system consists of 101 stations, of which 17 are underground or indoors.[29][30][31][32] The only underground station on the pre-metro western network was Nationaltheatret, and most of the underground station are in the common tunnel under the city center, or in shorter tunnel sections on the eastern network; in particular the Furuset Line runs mainly underground, with all but Haugerud built in or at the opening of a tunnel.[33]

Stations in the city center are located close to large employment centers as well as connection possibilities to other modes of transport, such as tram, rail and bus. All stations can be identified at ground level by signs with a blue T in a circle. Stations outside the center are unmanned since the 1995, with ticket machines for fare purchase;[14] some stations feature kiosks. A system of turnstiles have been installed, but will never be activated due to security issues. All stations have step-free accessibility through at least one entrance (except the inbound platform at Frøen), and the platform height is aligned with the train cars.[34]

Intermodality

[edit]

The metro is integrated into the public transport system of Oslo and Akershus through the agency Ruter, allowing tickets to also be valid on the Oslo Tramway, city buses, ferries, and the Oslo Commuter Rail operated by Vy.[35] A new, wireless ticketing system, Reisekort, has in the recent years been implemented.[36] As of June 2022, a single ticket for one zone (the entire metro system is in zone 1) costs NOK 39 for adults (a surcharge of 20 NOK is added if you buy onboard within zone 1);[37] a 30-day ticket costs NOK 814 for adults.[38] This includes all means of public transport within the zone where the ticket is first activated (again, for the metro, zone 1). There is a fine of NOK 950, or NOK 1150, for not having a valid ticket, depending on if the fine is paid on location or not.[39]

Oslo maintains a street tram system with six lines, of which two are suburban lines.[40] The street trams operate mostly within the borders of the Ring Line, providing a frequent service in the city centre, with lower average speeds but with more stops. There are major transfer points to the tramway at Majorstuen, Jernbanetorget, Jar, Storo and Forskningsparken.[41][42]

The commuter train serves suburbs further away from Oslo, though some of the commuter rail services remind of a rapid transit service, in particular line L1 to Lillestrøm and Asker, line L2 to Stabekk and Ski, and line R31 to Jaren with higher service frequency through the continual populated area of Oslo. Transfer to railway services is available at Jernbanetorget (to Oslo S) and Nationaltheatret, the latter with a considerably shorter walk.[43]

Bus services are provided to numerous stations. Most bus services provide feeding to the metro system where possible, and then do not continue into town. However, since the metro operates solely into town, instead of across it, many buses operate between stations on different lines, or provide alternative routes across town.[44]

Future expansion

[edit]As part of the political agreement Oslo Package 3, a number of changes and expansions have been proposed for the Oslo Metro.[45] Only one of these, the Fornebu Line, is currently being built[46] - the other projects have been put on hold for it.

Proposed

[edit]- Expansion of the Furuset Line to Lørenskog with stations at Skårer, Lørenskog Centre and a new terminus at Akershus University Hospital, with travel time to Jernbanetorget of 27 minutes.

- A second common tunnel from Majorstuen to Tøyen, creating two new stations at Bislett and southern Grünerløkka (Nybrua).[47] All lines will stop at Stortinget, which will get four platforms. Majorstuen station will be moved underground.[48]

Under construction

[edit]- The Fornebu Line is planned to run from Majorstuen to the old airport area at Fornebu, through Skøyen and Lysaker; a total of 6 new stations will be on this line. The line began construction in December 2020, with an opening date set around 2029, and will cost an estimated $2.6 billion USD.[49][46] The line is funded in part by Oslo and Akershus county, among other sources.[50]

Rolling stock

[edit]

The trains on the Oslo metro are currently exclusively the MX3000, ordered in 2003 to replace the oldest T1000 stock. Delivery started in 2006, and unlike older stock the MX3000 units are painted white instead of red. 83 three-car units were ordered in 2006;[24] a further 32 were ordered in December 2010.[51]

A number of versions of the T1000 stock have earlier been used on the Oslo metro. This includes 146 cars of the types T1 through T4, that have third-rail only operation, and thus did not run on the Holmenkollen and Kolsås lines. These ran usually in units of three or six (sometimes four or five) cars. Types T5 to T8, 49 in total, delivered with both third-rail and overhead wire equipment, normally ran on the Holmenkollen line (two cars) and Kolsås line (three cars).[21]

When the Holmenkollen Line was connected to the T-bane it was still using old teak cars; to allow through services the T2000, capable of dual-system running, was delivered in 1993. They were not particularly successful and only 12 units were delivered, operating in pairs on the Holmenkollen line sometimes connecting with the Lambertseter line, and scrapped in 2010.[52]

Depots and facilities

[edit]- Avløs Depot – located near Avløs station on the Kolsås Line, it has been closed for refurbishment since 2011 and reopened in August 2015.[53]

- Etterstad Depot – located on the shared section of the Østensjø Line, Furuset Line and the Lambertseter Line before Brynseng station, it is used as the main operations centre for the Oslo Metro and has a yard for maintenance of way equipment.

- Majorstuen Depot – a small yard used mainly for storing trains, located close to the Oslo Tramway Museum and Majorstuen station.

- Ryen Depot – the main storage and maintenance yard for all Oslo Metro trains, located on the Lambertseter Line near Ryen station.

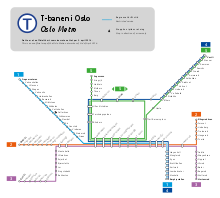

Network map

[edit]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Inline references

[edit]- ^ a b "Ruter Årsrapport 2016" [Ruter Årsrapport 2016] (PDF) (in Norwegian). Ruter. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-14. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- ^ a b "Årsrapport 2014" [Annual Report 2014] (PDF) (in Norwegian). Ruter. 2014. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-01-10. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- ^ Bjerke and Holom, 2004: 9

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 6

- ^ a b Aspenberg, 1994: 7

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 8

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 12

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 14

- ^ Bjerke and Holom, 2004: 347

- ^ a b Aspenberg, 1994: 17

- ^ Burtenshaw, D.; Bateman, M.; Ashworth, G. J. (29 June 2021). The European City: A Western Perspective. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-000-38316-4.

- ^ "venFakta om Nørreport Station". Archived from the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Bjerke and Holom, 2004: 346

- ^ a b c d e f Oslo T-banedrift. "Kort historikk" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2011-05-26. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 19

- ^ a b Aspenberg, 1994: 29

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 16

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 29–30

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 30

- ^ Oslo Sporveier. "Milepæler 1875–2005". Archived from the original on 2008-04-29. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ a b Aspenberg, 1994: 62

- ^ Akers Avis Groruddalen (2004-07-28). "Full stopp for Grorudbanen". Archived from the original on 2012-05-13.

- ^ Oslo T-banedrift. "Kolsåsbanen i mai" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2011-05-26. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ a b Oslo T-banedrift (2006). "Nye T-banevoger i prøvedrift" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-26.

- ^ Local Transport Historical Association. "Short about LTF". Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ a b Ruter (2016). "Rutetabell for T-banen" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

- ^ NTB (2020-12-11). "Byggestart for Fornebubanen". finansavisen.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2022-08-13. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- ^ Berg Bentzrød, Sveinung (January 25, 2017). "Smiler bredt, men vil ikke si når Fornebubanen skal stå ferdig". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Oslo T-banedrift (2008). "Linjekart" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-06.

- ^ Oslo Sporveier. "T-banestasjonene i Øst" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Oslo Sporveier. "T-banestasjonene i Vest" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Oslo Sporveier. "Holmenkollbanens stasjoner" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Aspenberg, 1994: 33

- ^ Ruter. "Tilgjengelighet for alle" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ Ruter. "Transportmidlene" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2008-04-28. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ^ Ruter. "Hva er Flexus" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2008-04-27. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ^ "Single ticket". Ruter. Archived from the original on 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ^ "Tickets and prices". Ruter. Archived from the original on 2016-08-23. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ^ Ruter. "Ticket inspections". Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Bjørn and Holum, 2004: 344

- ^ Oslo Sporvognsdrift (2007). "Trikken 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ^ Ruter (2013-12-15). "Linjekart med T-banens stasjoner fra 15.12.2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-24.

- ^ Ruter (2007). "Skinne 2007" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-08-07.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ruter (2007). "Buss Alle 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ^ Akershus County Municipality (2006-05-29). "Oslopakke 3" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2011-07-19.

- ^ a b "The Fornebu Line". Oslo kommune. 2022-03-24. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-28.

- ^ "Ny T-banetunnel gjennom Oslo sentrum". Ruter (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2019-11-01.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bentzrød, Christian Sørgjerd Sveinung Berg. "Foreslår nye T-banestasjoner på Bislett og Grünerløkka". Aftenposten (in Norwegian Bokmål). Archived from the original on 2022-08-13. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- ^ NRK (2022-06-23). "Viken vedtok Fornebubanen". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Archived from the original on 2022-06-28. Retrieved 2022-06-28.

- ^ "Fornebubanen". Oslo kommune (in Norwegian). 2017-09-27. Archived from the original on 2022-06-26. Retrieved 2022-06-28.

- ^ "Railway Gazette: Oslo orders more metro cars". 2010-12-24. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ^ Oslo T-banedrift. "T-2000" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Budstikka.no (23 February 2013). "Avløs: Gammel hall får ny nabo". Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aspenberg, Nils Carl (1994). Trikker og forstadsbaner i Oslo. Oslo: Baneforlaget. ISBN 82-91448-03-5.

- Bjerke, Thor & Holom, Finn (2004). Banedata 2004. Oslo / Hamar: Norsk Jernbaneklubb / Norsk Jernbanemuseum. ISBN 82-90286-28-7.

External links

[edit]- Sporveien T-banen (in Norwegian)

- Ruter (in Norwegian)