Vlach law

The Vlach law (Latin: ius valachicum, Romanian: legea românească, "Romanian law", or obiceiul pământului, "customs of the land", Hungarian: vlach jog) refers to the traditional Romanian common law as well as to various special laws and privileges enjoyed or enforced upon particularly pastoralist communities (cf. obști) of Romanian stock or origin in European states of the Late Middle Ages and Early modern period, including in the two Romanian polities of Moldavia and Wallachia, as well as in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Serbia, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, etc.

The first documents associated with settlement with the Vlach law began to appear in the 14th century. The main characteristics of the Vlach law, regardless of location:[1]

- The right to travel and carry weapons (sometimes right to hunt).

- Not mandatory labour service towards the land owner, taxes were paid by live or in money.

- Military service obligation towards the country (forms depending on the country).

The term "Vlachs" originally denoted Romance-speaking populations; the term became synonymous in some contexts with "shepherds", but even in these cases an ethnical aspect was implicit. The establishment around them of a large number of "slaves" starting from the 6th century led to the linguistic Slavization of a significant number of these communities, so that in the 8th century, the word "Vlach" came, in Slavic languages, to designate any Orthodox shepherd, whether he remained Romanophone (as in the Kingdom of Eastern Hungary and the Principality of Transylvania) or became Slavophone (as in a large part of the Balkan Peninsula).[2] The concept originates in the laws enforced on Vlachs in the medieval Balkans.[3] In medieval Serbian charters, the pastoral community, primarily made up of Vlachs, were held under special laws due to their nomadic lifestyle.[4] In late medieval Croatian documents Vlachs were held by special law in which "those in villages" pay tax and "those without villages" (nomads) serve as cavalry.[5] Until the 16th century term Vlachs was used not only to describe a representative of the Vlach law or pastoral profession, it also had an ethnic meaning which was lost in the 17th century, although was still used for people (sheepherder) regardless of their origin.[6]

Vlach law in the Kingdom of Hungary

[edit]

The expression "ius valachicum" appears in documents issued in the Kingdom of Hungary in the 14th century, referring to a type of law followed by the Romanian population in the kingdom. The classic exposition was published in 1517, in the Tripartitum by Stephen Werbőczy a Hungarian statesman and legal theorist, this systematised the legal customs of the Kingdom of Hungary.[7]

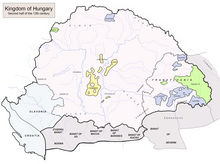

The Vlach law was a set of laws regulating the way of life and farming of the Central European and Balkan peoples practicing transhumance pastoralism that has been also introduced in the Kingdom of Hungary. In Hungarian historiography, due to the settlement activities of the kenezes, villages with Vlach law arose in the Kingdom of Hungary between the 13th and 16th centuries, initially mostly inhabited by Romanians (Vlachs) and Ruthenians. The very first villages with Vlach law were established in Transylvania, their numbers increased, and spread in Upper Hungary, and in other parts of the Kingdom of Hungary, primarily in mountainous areas, also in Moravian Wallachia and in Galicia. This way of life was also adopted by a part of the Ruthenian population of today's Transcarpathia from the 14th century. Mostly shepherds lived in their villages with the Vlach law. According to this law, people were settled where the natural conditions were not favorable for farming. Its essential elements were the unique taxation methods. As the law had a more freedom of degree of taxation, it was favoring the immigration of foreigners.[8]

This type of "common law" used by the Romanian population in the late medieval Kingdom of Hungary, cognates with the law used in Moldavia and Wallachia. In the Kingdom of Hungary, the unwritten law (customary law) coexisted with the written law (royal decrees), they had the same authority and were applied accordingly in the courts. The law is connected to the so-called Romanian districts "districta Valachorum". The first Romanian districts are mentioned in the 14th century, after they become more visible in the records. That districts being encountered throughout the Kingdom of Hungary are not specific to a Romanian population, the term depending upon context differed in its meaning. These Romanian districts had some sort of legal autonomy, where people might use Romanian customary law. Cases according to the Vlach law were more common in Transylvania, Máramaros County, Zaránd County and the Banat, where the Romanian population was most dense in the Kingdom of Hungary. The Banat highlands preserved specific legal practices until the late 17th century, that were recognised by officials of the Kingdom of Hungary and by the Principality of Transylvania. The Vlach law had roots in the Romano-Byzantine legal tradition which was influenced by the Hungarian customary law.[7]

In Hungarian historiography, the origin of Vlach law, that the kenez was not only chieftain, but also a settlement contractor, who receives some uninhabited land from the king in order to settle it and then he and his descendants judge over the settlers in non-principal matters. These areas are smaller or larger in proportion to the size of the donated land. There were kenezes with 300 families, but also ones with barely four or five families. As a result, there was a big difference in authority and rank between the individual kenezes. Initially, they settled in the vicinity of existing villages, but from the middle of the 14th century, they also founded independent settlements.[9]

In a certificate of King Louis the Great of Hungary dated 1350: "hoping that under their diligent care our Vlach villages will gain many inhabitants, we give the keneziatus". A document dated in 1352, in which the lord-lieutenants of Krassó County writes the following: "They asked me for the uninhabited land of the Mutnok stream with the same freedom as the kenezes living in the Sebes district rule their villages in order to populate it." In the beginning the Romanians settled only on the royal estates, later the king allowed the Bishop of Transylvania and the chapter to settle Romanians on their estates. In the time of King Louis the Great, cities and even private landlords could settle immigrant Romanians.[9]

In Hungarian historiography, the Romanian immigrants in the Kingdom of Hungary are invariably characterized in Hungarian sources as mountain shepherds. As late as the 16th century, an official report referred to Romanians as people who kept many animals in the forests and mountains. The "sheep tax" (quinquagesima ovium, meaning "sheep fiftieth") was paid only by the Romanians, a people closely identified with sheep-breeding. The tax required the delivery of one sheep for every fifty sheep held. Since the mountain-dwelling Romanians practised but subsistence farming, they were not taxed on their agricultural output.[10]

According to Romanian historiography, the knezes were the representatives of autochthonous population and their settling activities were taken close to their village, new groups of houses being built at the outer limit of an old settlement. Knezes in lowland areas lost their influence and title quicker as their lands came under feudal lords, while those in higher areas maintained their customs for longer, such as in areas of Hațeg, Banat, and Maramureș. Some voivodes and knezes rebelled against the King and passed over to Moldavia and Wallachia where they established their own rule, while those in conflict with the new authority move into the Kingdom of Hungary.[11]

Contrary to the name of this law, not only the Romanians (Vlachs), but also other peoples were entitled to this right. The Vlach word in the 15–16th centuries no longer primarily meant a people, but an occupation and a way of life, the village with Vlach law was not only the place of residence of the Romanian or Ruthenian population, Slovaks, Poles, Croats and Hungarians also settled according to the more free Vlach law, favorable to the immigration of foreigners.[8]

Voivode was the title of a leader who held authority over several kenezes. Sources dating from the 14th century confirm that whereas kenez was a hereditary title, the voivodes were initially elected by the Romanians, which was a practice consistent with Hungarian customary law, which provided that immigrant groups elect a leader from their ranks. (Székelys elected their captains and judges, Saxons elected the magistrates who worked alongside the royal court), and ). The voivodes followed the example of the kenezes and obtained that their status and privileges be passed on to their heirs. The hereditary status of voivodes and kenez did not deprive ordinary Romanians of their legal and economic rights, those rights were recognized by the castellans at the head of Hungarian castle districts. In the district courts, in accordance with Hungarian administrative practice, they appointed not only kenezes but also Romanian priests and commoners, and the courts followed Romanian customary law in rendering judgment.[10]

The most important characteristics of the legal status of villages with Vlach law were the following:[8]

- The judge of the resettled population is the settler kenezes, or was his heir, and the court of Hungarian royal officers judged the kenez.

- One third of the amount of fines imposed on the people went to the kenez, and two thirds could be used by the villages for their own needs.

- The villages could redeem their public service obligation with a tenth of their produce.

- The population gave a royal fiftieth of their animals.

The Banate of Severin had territories of several Vlach knezes, they were bound to provide tribute to support the province, and to assist as warriors at the defense of the area. After the rebellion of Basarab, several Romanian knezes fled into Hunyad, Krassó, and Temes counties. The refugees were settled in small districts, they took place next to other territories which had been earlier established in the Kingdom of Hungary by Romanian knezes. These knezes were entrusted with the duty to populate private and royal estates. The Romanian knezes in return for their settlement activities, obtained permanent leadership of the settlements which they had founded and they acquired rights to revenues. In the early 14th century, it was recorded about 40 Romanian districts, which stretched through eastern Hungary and Transylvania, northwards to Máramaros.The Romanian districts comprised estates possessed by the Romanian knezes where the Romanian peasantry worked, some of these had over a hundred peasants. The knezes held the title of nobles, however the knezes were not qualified as full nobles, because they were obligated to pay duties to the castle in exchange for their estates. The duties of the Romanian knezes varied according to the district and to the individual conditions under which their ancestors had initially acquired and settled the land: to provide a single mounted warrior for guarding the Danube river against intrusion, and to supply livestock, including delivery of the "sheep fiftieth".[12]

In Romanian historiography the law originates from Ancient times on the lands inhabited by Romanians.[13] The customary law comes from the Roman habit of land distribution were "sortes" (Romanian: sorți) were drawn, the land was divided in falces (Romanian: fălci), the neighbouring falces owner was a vicinus (Romanian: vecin). The uphold of the law was overseen by judes (Romanian juzi) a title that was replaced by the Slavic word knez.[13] The structure of early feudal Romanian society had a jude and a ducă, two titles later renamed under Slavic influence as cneaz and voievod. While the voievod had mostly military duties, the kneaz was the representative of legal authority. As such, during Arpad dynasty knezes that were not on church or nobility lands were under royal authority and became its representatives to the community, including the application of the law. In this context, many knezes acted as minor nobility, holding the title hereditarily and expanding their rule by new settlements in neighbouring areas. Their settling activities were taken within their districts, new groups of houses being built at the outer limit of an old settlement. After the breakaway of Wallachia, knezes in conflict with the new authority moved to the Kingdom of Hungary[14] The situation reversed during the Angevine dynasty, in particular with the Decree of Turda that took an explicitly negative action against Romanians, and required that knezes were vested by the law of the kingdom rather than customary law.[13]

According to Romanian historian Ioan-Aurel Pop, in Transylvania, after the establishment of the Union of Three Nations and the suppression of the Bobâlna Uprising in 1438, the Vlach law gradually disappeared while the Romanian masters and boyars (which enjoyed the Universitas Valachorum) had to choose between three solutions: the loss of all rights and the fall into serfdom, having to migrate beyond the Carpathians to Moldavia or Wallachia, or merging into the Hungarian nobility by converting to Catholicism and adopting the Hungarian language.[15][16]

A document from 1436 issued by Ivan VI Frankopan illustrates the relation between Vlachs and local rulers. Among the most important regulations are the military and fiscal duties of the Vlachs who are required to participate with "shield and sword" or pay a fine. In return Vlachs required that no foreign knez and voivode would rule over them.[17][18][19]

The Military Frontier was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy against incursions from the Ottoman Empire. The establishment of the new defense system in Hungary and Croatia took place in the 16th century and fortresses were built in the area of the Military Frontier. When the area became inhabited, the residents got hereditary possession of the land. The border guards had a self-government and were linked to this centralized military and political order through their right of land ownership and personal freedom. In this way, the Habsburgs achieved several objectives such as a cheap army for border defense. As another result, the border guards were extremely loyal to the Habsburg king and he could utilize them not only against the Ottomans but also for internal conflicts against peasants and nobles. When the Military Frontier was established, many former serfs, nomadic farmers and immigrants from the Ottoman Empire-occupied areas were tasked with guarding the borders. Among them, the Vlachs and brigands were the most different groups that acquired privileges in the 17th century, thus they became privileged classes of society by the Vlach law and brigand privileges. The Vlachs, who emigrated from the Balkans, brought along their customary law as an old Slavic social economic community. They also had dukes as military commanders and a self-government and judicial system. The Vlachs were tasked with guarding the borders, supervising major roads and mountain paths to ensure the safety of passengers and cargo transports. In return, the Habsburg monarchs gave them other privileges and tax reductions.[20]

Jus Valachicum continued to be in use in the 18th century in the area of Mărginimea Sibiului and, in a particular format, in the area of Făgăraș where the last modification to the statutes was made in 1885.[21]

Vlach law in the Kingdom of Serbia

[edit]The equivalent of ius Valachichum, Zakon Vlachom is a collection of norms from the 14th century based on three monastic charters: Banjska Monastery Charter issued by king Stefan Milutin in 1313–16, Hilandar Monastery Charter from 1343-1345, and Prizren Monastery Charter from 1348–53. The law distinguished between two categories of Vlachs: soldiers and chelators, and determined the obligations and taxation forms: Vlachs who paid a big tenth of tithe (representing a tenth of livestock) were exempted from paying any other dues to the monarch, while Vlachs that paid a small tithe had to do various chores for the monasteries (such as wool processing, manufacturing wool products etc.).[22]

Vlach law in the Habsburg Empire

[edit]In the Habsburg monarchy, in 1630, the Vlach Statutes (Statuta Valachorum) were enacted which defined the tenancy rights and taxation of Orthodox refugees in the Military Frontier; land were granted in return for military service.[23] In the 16th and 17th centuries Slavic pastoral communities (such as Gorals) under the Vlach law were settled in the northern Kingdom of Hungary.[24] The colonization of peoples under the Vlach law resulted in ethnic enclaves of Czechs, Poles and Ruthenians in historical Hungary.[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Czamańska, Ilona (2015). "The Vlachs – Several Research Problems". Balcanica Posnaniensia Acta et Studia. 22 (1). Poznań – Bucharest: 7. doi:10.14746/bp.2015.22.1.

- ^ Murvar, Vatro (1956). The Balkan Vlachs: a typological study. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 20.

- ^ Du Nay, Alain; Du Nay, André; Kosztin, Árpád (1997). Transylvania and the Rumanians. Matthias Corvinus. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-882785-09-4.

- ^ Filipović, Gordana (1989). Kosovo--past and present. Review of International Affairs. p. 25.

- ^ Cebotarev, Andrej (June 1996). "Review of Stećaks (Standing Tombstones) and Migrations of the Vlasi (Autochthonous Population) in Dalmatia and Southwestern Bosnia in the 14th and 15th Centuries". Povijesni prilozi [Historical Contributions] (in Croatian). 14 (14). Zagreb: Croatian Institute of History: 323.

- ^ Gawron, Jan (2020). "Locators of the settlements under Wallachian law in the Sambor starosty in XVth and XVIth c. Territorial, ethnic and social origins". Balcanica Posnaniensia. Acta et Studia. 26: 274–275. doi:10.14746/bp.2019.26.15. S2CID 213877208.

- ^ a b Magina, Adrian (2013). "From Custom to Written Law: Ius Valachicum in the Banat". In Rady, Martyn; Simion, Alexandru (eds.). Government and Law in Medieval Moldavia, Transylvania and Wallachia. School of Slavonic and East European Studies UCL. ISBN 978-0-903425-87-2.

- ^ a b c Bárth, János (1982). "vlachjogú falu" [Village with Vlach law]. In Ortutay, Gyula; Bodrogi, Tibor; Diószegi, Vilmos; Fél, Edit; Gunda, Béla; Kósa, László; Martin, György; Pócs, Éva; Rajeczky, Benjamin; Tálasi, István; Vincze, István; Kicsi, Sándor; Nagy, Olivérné; Csikós, Magdolna; Koroknay, István; Kádár, József; Máté, Károly; Süle, Jenő (eds.). Magyar néprajzi lexikon - Ötödik kötet [Hungarian Ethnographic Lexicon - Volume V] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó - Ethnography Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Science. ISBN 963-05-1285-8.

- ^ a b Dr. Jancsó, Benedek. "Erdély története az Anjou-ház uralkodása alatt" [History of Transylvania during the reign of the House of Anjou]. Erdély története [History of Transylvania] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Cluj-Kolozsvár: Minerva. p. 63.

- ^ a b Makkai, László (2001). "The Mongol Invasion and Its Consequences". History of Transylvania Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606 - III. Transylvania in the Medieval Hungarian Kingdom (896–1526) - 3. From the Mongol Invasion to the Battle of Mohács. Columbia University Press, (The Hungarian original by Institute of History Of The Hungarian Academy of Sciences). ISBN 0-88033-479-7.

- ^ Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1996). Românii și maghiarii în secolele IX-XIV. Geneza statului medieval în Transilvania] [Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th Century. The Genesis of the Transylvanian Medieval State]. Center for Transylvanian Studies. p. 49

- ^ Rady, Martyn (2000). Nobility, land and service in medieval Hungary. PALGRAVE, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York. pp. 91–93. ISBN 0-333-71018-5.

- ^ a b c Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1996). Românii și maghiarii în secolele IX-XIV. Geneza statului medieval în Transilvania] [Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th Century. The Genesis of the Transylvanian Medieval State]. Center for Transylvanian Studies. p. 49.

- ^ Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1997). Istoria României. Transilvania [History of Romania. Transylvania]. Editura George Barițiu. pp. 451–543.

- ^ Pop, Ioan Aurel (1999). Romanians and Romania: a brief History. Columbia University Press 1999. ISBN 0-88033-440-1.

- ^ Filipașcu, Alexandru (1945). "L'Ancienneté des Roumains de Marmatie" [The seniority of Romanians from Marmatia]. Bibliotheca rerum Transsilvaniae (in French). pp. 8–33.

- ^ Dragomir, Silviu (1924). Originea coloniilor române din Istria] [Origin of Romanian Colonies in Istria]. Cultura Națională. pp. 3–4, [1].

- ^ Ilona Czamańska; (2015) The Vlachs – several research problems p. 14; BALCANICA POSNANIENSIA XXII/1 IUS VALACHICUM I, [2]

- ^ Srđan Rudić, Selim Aslantaş: State and Society in the Balkans Before and After Establishment of Ottoman Rule, pages 33-34

- ^ Heka, Ladislav (2019). "The Vlach law and its comparison to the privileges of Hungarian brigands". Podravina: časopis za geografska i povijesna multidisciplinarna istraživanja. 18 (35). Koprivnica, Croatia: 26–45.

- ^ Cosma, Ela (September 2022). "Enacted "Jus Valachicum" in South Transylvania (14th-18th Centuries)". ResearchGate. p. 4. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ Miloš Luković: Zakon Vlachom (Jus Valachicum) in the Charters Issued to Serbian Medieval Monasteries and Kanuns Regarding Vlachs in the Early Ottoman Tax Register, 2015, page 36

- ^ Lampe, John R.; Jackson, Marvin R. (1982). Balkan Economic History, 1550-1950: From Imperial Borderlands to Developing Nations. Indiana University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-253-30368-0.

- ^ Kocsis, Karoly; Hodosi, Eszter Kocsisne (1 April 2001). Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Simon Publications LLC. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-931313-75-9.

- ^ Ethnographia. Vol. 105. A Társaság. 1994. p. 33.