Lernaean Hydra

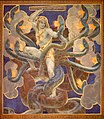

Gustave Moreau's 19th-century depiction of the Hydra, influenced by the Beast from the Book of Revelation | |

| Family | Child of Typhon and Echidna |

|---|---|

| Folklore | Greek mythology |

| Country | Greece |

| Region | Lerna |

The Lernaean Hydra or Hydra of Lerna (Ancient Greek: Λερναῖα ὕδρα, romanized: Lernaîa Húdrā), more often known simply as the Hydra, is a serpentine lake monster in Greek mythology and Roman mythology. Its lair was the lake of Lerna in the Argolid, which was also the site of the myth of the Danaïdes. Lerna was reputed to be an entrance to the Underworld,[1] and archaeology has established it as a sacred site older than Mycenaean Argos. In the canonical Hydra myth, the monster is killed by Heracles (Hercules) as the second of his Twelve Labors.[2]

According to Hesiod, the Hydra was the offspring of Typhon and Echidna.[3] It had poisonous breath and blood so virulent that even its scent was deadly.[4] The Hydra possessed many heads, the exact number of which varies according to the source. Later versions of the Hydra story add a regeneration feature to the monster: for every head chopped off, the Hydra would regrow two heads.[5] Heracles required the assistance of his nephew Iolaus to cut off all of the monster's heads and burn the neck using a sword and fire.[6]

Development of the myth

[edit]The oldest extant Hydra narrative appears in Hesiod's Theogony, while the oldest images of the monster are found on a pair of bronze fibulae dating to c. 700 BC. In both these sources, the main motifs of the Hydra myth are already present: a multi-headed serpent that is slain by Heracles and Iolaus. While these fibulae portray a six-headed Hydra, its number of heads was first fixed in writing by Alcaeus (c. 600 BC), who gave it nine heads. Simonides, writing a century later, increased the number to fifty, while Euripides, Virgil, and others did not give an exact figure. Heraclitus the Paradoxographer rationalized the myth by suggesting that the Hydra would have been a single-headed snake accompanied by its offspring.[7]

Like the initial number of heads, the monster's capacity to regenerate lost heads varies with time and author. The first mention of this ability of the Hydra occurs with Euripides, where the monster grew back a pair of heads for each one severed by Heracles. In the Euthydemus of Plato, Socrates likens Euthydemus and his brother Dionysidorus to a Hydra of a sophistical nature who grows two arguments for every one refuted. Palaephatus, Ovid, and Diodorus Siculus concur with Euripides, while Servius has the Hydra grow back three heads each time; the Suda does not give a number. Depictions of the monster dating to c. 500 BC show it with a double tail as well as multiple heads, suggesting the same regenerative ability at work, but no literary accounts have this feature.[8]

The Hydra had many parallels in ancient Near Eastern religions. In particular, Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian mythology celebrated the deeds of the war and hunting god Ninurta, whom the Angim credited with slaying 11 monsters on an expedition to the mountains, including a seven-headed serpent (possibly identical with the Mushmahhu) and Bashmu, whose constellation (despite having a single Head) was later associated by the Greeks with the Hydra. The constellation is also sometimes associated in Babylonian contexts with Marduk's dragon, the Mushhushshu.

Second Labor of Heracles

[edit]

Eurystheus, the king of the Tiryns, sent Heracles (or Hercules) to slay the Hydra, which Hera had raised just to slay Heracles. Upon reaching the swamp near Lake Lerna, where the Hydra dwelt, Heracles covered his mouth and nose with a cloth to protect himself from the poisonous fumes. He shot flaming arrows into the Hydra's lair, the spring of Amymone, a deep cave from which it emerged only to terrorize neighboring villages.[9] He then confronted the Hydra, wielding either a harvesting sickle (according to some early vase-paintings), a sword, or his famed club. Heracles then attempted to cut off the Hydra's heads but each time that he did so, one or two more heads (depending on the source) would grow back in its place. The Hydra was invulnerable as long as it retained at least one head.

The struggle is described by the mythographer Apollodorus:[10] realizing that he could not defeat the Hydra in this way, Heracles called on his nephew Iolaus for help. His nephew then came upon the idea (possibly inspired by Athena) of using a firebrand to scorch the neck stumps after each decapitation. Heracles cut off each head and Iolaus cauterized the open stumps. Seeing that Heracles was winning the struggle, Hera sent a giant crab to distract him. He crushed it under his mighty foot. The Hydra's one immortal head was cut off with a golden sword given to Heracles by Athena. Heracles placed the head—still alive and writhing—under a great rock on the sacred way between Lerna and Elaius,[9] and dipped his arrows in the Hydra's poisonous blood. Thus, his second task was complete.

The alternate version of this myth is that after cutting off one head he then dipped his sword in its neck and used its venom to burn each head so it could not grow back. Hera, upset that Heracles had slain the beast she raised to kill him, placed it in the dark blue vault of the sky as the constellation Hydra. She then turned the crab into the constellation Cancer.

Heracles would later use arrows dipped in the Hydra's poisonous blood to kill other foes during his remaining labors, such as Stymphalian Birds and the giant Geryon. He later used one to kill the centaur Nessus; and Nessus' tainted blood was applied to the Tunic of Nessus, by which the centaur had his posthumous revenge. Both Strabo and Pausanias report that the stench of the river Anigrus in Elis, making all the fish of the river inedible, was reputed to be due to the Hydra's poison, washed from the arrows Heracles used on the centaur.[11][12][13]

When Eurystheus, the agent of Hera who was assigning The Twelve Labors to Heracles, found out that Iolaus had handed Heracles the firebrand, he declared that the labor had not been completed alone and as a result did not count toward the ten labors set for him. The mythic element is an equivocating attempt to resolve the submerged conflict between an ancient ten labors and a more recent twelve.

Constellation

[edit]

Greek and Roman writers related that Hera placed the Hydra and crab as constellations in the night sky after Heracles slew him.[14] When the sun is in the sign of Cancer (Latin for "The Crab"), the constellation Hydra has its head nearby. In fact, both constellations derived from the earlier Babylonian signs: Bashmu ("The Venomous Snake") and Alluttu ("The Crayfish").

In art

[edit]-

Mosaic from Roman Spain (AD 26)

-

Silver sculpture (1530s)

-

Engraving (1) by Hans Sebald Beham

-

Gustave Moreau (1861)

-

John Singer Sargent (1921)

-

A modern version by Nikolai Triik

-

Reverse of a 1914 medal by Fritz Eue commemorating General Erich Ludendorff[15]

Classical literature sources

[edit]Chronological listing of classical literature sources for the Lernaean Hydra:

- Hesiod, Theogony 313 ff (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic poetry C8th or 7th BC)

- Alcman, Fragment 815 Geryoneis (Greek Lyric trans. Campbell Vol 3) (Greek lyric poetry C7th BC)

- Alcaeus, Fragment 443 (from Schoiast on Hesiod's Theogony) (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric II) (Greek lyric poetry C6th BC)

- Simonides, Fragment 569 (from Servius on Virgil's Aeneid) (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric II) (Greek lyric poetry C6th to 5th BC)

- Aeschylus, Leon, Fragment 55 (from Stephen of Byzantium, Lexicon 699. 13) (trans. Weir Smyth) (Greek tragedy C5th BC)

- Sophocles, Trachinae 1064–1113 (trans. Oates and O'Neil) (Greek tragedy C5th BC)

- Euripides, The Madness of Hercules 419 ff (trans. Way) (Greek tragedy C5th BC)

- Euripides, Hercules 556 ff (trans. Oates and O'Neil) (Greek tragedy C5th BC)

- Plato, Euthydemus 297c (trans. Lamb) (Greek philosophy C4th BC)

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 4. 1390 ff (trans. Rieu) (Greek epic poetry C3rd BC)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 11. 5 (trans. Oldfather) (Greek history C1st BC)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 38. 1

- Virgil, Aeneid 6. 287 ff (trans. Fairclough) (Roman epic poetry C1st BC)

- Virgil, Aeneid 6. 803 ff (trans. Day-Lewis) (Roman epic poetry C1st BC)

- Propertius, Elegies, 2. 24a. 23 ff (trans. Butler) (Latin poetry C1st BC)

- Lucretius, Of The Nature of Things 5 Proem 1 (trans. Leonard) (Roman philosophy C1st BC)

- Strabo, Geography 8. 3. 19 (trans. Jones) (Greek geography C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Strabo, Geography 8. 6. 2

- Strabo, Geography 8. 6. 6

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 9. 69 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic poetry C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 9. 129 & 158 ff

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 9. 192 ff

- Ovid, Heroides 9. 87 ff (trans. Showerman) (Roman poetry C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Ovid, Heroides 9. 115 ff

- Philippus of Thessalonica, The Twelve Labors of Hercules (The Greek Classics ed. Miller Vol 3 1909 p. 397) (Greek epigram C1st AD)

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 44 (trans. Miller) (Roman tragedy C1st AD)

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 220 ff

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 241 ff

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 526 ff

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 776 f

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 1194 ff

- Seneca, Agamemnon 833 ff (trans. Miller) (Roman tragedy C1st AD)

- Seneca, Medea 700 ff (trans. Miller) (Roman tragedy C1st AD)

- Seneca, Hercules Oetaeus 17-30 (trans. Miller) (Roman tragedy C1st AD)

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 3. 224 (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic poetry C1st AD)

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 7. 623 ff

- Statius, Thebaid 2. 375 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic poetry C1st AD)

- Statius, Thebaid 4. 168 ff

- Statius, Silvae 2. 1. 228 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic poetry C1st AD)

- Statius, Silvae 5. 3. 260 ff

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, The Library 2. 5. 2 (trans. Frazer) (Greek mythography C2nd AD)

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, The Library 2. 7. 7

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 37. 4 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue C2nd AD)

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 3. 18. 10 - 16

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 5. 9

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 17. 11

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 26. 7

- Aelian, On Animals 9. 23 (trans. Scholfield) (Greek natural history C2nd AD)

- Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Book 2 (summary from Photius, Myriobiblon 190) (trans. Pearse) (Greek mythography C1st to C2nd AD)

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae Preface (trans. Grant) (Roman mythography C2nd AD)

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 30

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 34

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 151

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Astronomica 2. 23

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 5. 5 (trans. Conyreare) (Greek sophistry C3rd AD)

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 6. 10

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 6. 212 ff (trans. Way) (Greek epic poetry C4th AD)

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 9. 392 ff

- Nonnos, Dionysiaca 25. 196 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic poetry C5th AD)

- Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy 4. 7. 13 ff (trans. Rand & Stewart) (Roman philosophy C6th AD)

- Suidas s.v. Hydran temnein (trans. Suda On Line) (Greco-Byzantine Lexicon C10th AD)

- Suidas s.v. Hydra

- Tzetzes, Chiliades or Book of Histories 2. 237 ff (trans. Untila et al.) (Greco-Byzantine history C12 AD)

- Tzetzes, Chiliades or Book of Histories 2. 493 ff

See also

[edit]- Basilisk

- Feathered Serpent

- Horned Serpent

- Prehistoric snakes

- Python (mythology)

- Scylla

- Snakes in mythology

- Titanoboa

Citations

[edit]- ^ Kerenyi (1959), p. 143.

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 26.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 310 ff.. See also Hyginus, Fabulae Preface & 151

- ^ According to Hyginus, Fabulae 30, the Hydra "was so poisonous that she killed men with her breath, and if anyone passed by when she was sleeping, he breathed her tracks and died in the greatest torment."

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 29–30.

- ^ Greenley, Ben; Menashe, Dan; Renshaw, James (2017-08-24). OCR Classical Civilisation GCSE Route 1: Myth and Religion. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781350014886.

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 27–29.

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 30.

- ^ a b Kerenyi (1959), p. 144.

- ^ Apollodorus, 2.5.2.

- ^ Strabo, 8.3.19

- ^ Pausanias, 5.5.9

- ^ Grimal (1986), p. 219.

- ^ Eratosthenes, Catasterismi.

- ^ "Ludendorff". London: Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

General and cited references

[edit]- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press.

- Grimal, Pierre (1986). The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (1903). Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, The Myths of Hyginus. Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Kerenyi, Carl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks.

- Ogden, Daniel (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199557325.

- Piccardi, Luigi (2005). The head of the Hydra of Lerna (Greece). Archaeopress, British Archaeological Reports, International Series N° 1337/2005, 179-186.

- Ruck, Carl; Staples, Danny (1994). The World of Classical Myth.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 33–34.

- "Statue of Heracles battling the Lernaean Hydra at the southern entrance to the Hofburg (Imperial Palace) in Vienna". Britannica Encyclopaedia.

- "Statue of the Hydra battling Hercules at the Louvre". cartelen.louvre.fr. 1525.

![Reverse of a 1914 medal by Fritz Eue commemorating General Erich Ludendorff[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/Medaillie_General_Erich_Ludendorff_1914_FRZ_EUE_BERLIN.jpg/120px-Medaillie_General_Erich_Ludendorff_1914_FRZ_EUE_BERLIN.jpg)