Nettlecombe Court

| Nettlecombe Court | |

|---|---|

Nettlecombe Court Field Centre and the Church of St Mary the Virgin | |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Williton |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°07′52″N 3°21′00″W / 51.131°N 3.35°W |

Nettlecombe Court and park is an old estate on the northern fringes of the Brendon Hills, within the Exmoor National Park. They are within the civil parish of Nettlecombe, named after the house, and are approximately 3.6 miles (5.8 km) from the village of Williton, in the English county of Somerset. It has been designated by English Heritage as a Grade I listed building.[1]

The 16th-century Elizabethan, Tudor and Medieval architecture with Georgian refinements includes a mansion, Medieval hall, church, monumental oak grove, and a farm. It is surrounded by 60 hectares (150 acres) of estate parkland situated within the Exmoor National Park, once a part of the estate. It lays sheltered at the northeast incline of the Brendon Hills. The park surrounding the house is Grade II listed on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[2]

Nettlecombe Park blends into woodlands, with the house serving as the Leonard Wills Field Centre run by Field Studies Council and offering residential and non-residential fieldwork for schools, colleges and universities, holiday accommodation and professional and leisure courses in natural history and arts. Today, nearby hills and woodlands, including Exmoor National Park, have provided opportunities for general scientific introductory field courses on environmental themes and botany. Habitats include marine, freshwater and heather moorland and the surrounding settlements range from hamlets to villages to the country town of Taunton. An archaeological excavation on the edge of the property, near the sea coast, has revealed the remains of Danish Vikings who were defeated there circa 900.

History

[edit]

Nettlecombe was originally spelled Netelcumbe and by 1245 Nettelcumbe meaning the place or valley where the nettles grow.[3]

Nettlecombe has never been bought or sold. It was held before the Norman Conquest by Prince Godwine, son of King Harold. William the Conqueror assumed possession of Nettlecombe after defeating King Harold at the Battle of Hastings.[4] In 1160, Henry II granted it to Hugh de Raleigh, and to his heirs in perpetuity.[5] It passed to Warine de Raleigh, and on through direct blood heirs until the 19th century, a claim strengthened by marriages between deep ancestral cousins. The estate became a seat of the Trevelyan baronets (previously spelled as Trevilian), who also held another manor at Basil, by the marriage of Sir John Trevilian in 1481 to Lady Whalesborough, heiress of Nettlecombe via her Raleigh maternal line. Nettlecombe was held in continuity by Trevilian successors until the 20th century following the death of Joan Trevelyan and her husband Garnet Ruskin Wolseley.[6]

It became a boarding school for girls (St. Audries Junior School) in the late 1950s. Since 1967 it has been the home of the Leonard Wills Field Centre run by the Field Studies Council an educational charity.[7] The house is surrounded by Nettlecombe Park, a 90.4 hectares (223 acres) Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

House

[edit]

Nettlecombe Court is an Elizabethan country mansion, in addition to earlier-built structures including a late Medieval hall, entrance front, porch, a great hall, and church.[8] A Tudor parlour was added in 1599. In the 1640s there were further additions to the rear of the great hall following a fire started by roundheads opposed to George Trevelyns support of the monarchy during the English Civil War.[9]

During the reign of George I, between 1703 and 1707, the South West front was extended.[8] The south west wing was decorated in the 1780s and the north east service range was added in the early 19th century. The house contains plaster work from each of these eras.[10]

In the 17th century, an organ built by John Loosemore was installed, at a cost of £100.[11][12] This was converted from a single-manual to two-manual operation in the 1830s. In the 1980s, this was partly dismantled and the original parts removed to the John Loosemore Centre in Buckfastleigh, where they are still located, awaiting restoration.[13]

Family

[edit]

As stated in Nettlecombe Court, compiled by R. J. E. Bush, "Nettlecombe is first mentioned in the Domesday book of 1086, when it was stated to be held by William the Conqueror, and in the charge of his Sheriff for Somerset, William de Mohun."

Ralegh-Raleigh: In the mid-12th century John, son of William the Marshall, gifted the manor of Nettlecombe to Hugh de Ralegh, a Norman knight; and the gift was confirmed by a charter of Henry II in 1156. Later in the 12th century Warrin de Ralegh, Hugh's nephew, built a manor house on the site now occupied by Nettlecombe Court. The Court's kitchen may have formed the original 12th-century Great Hall. Ralegh also built a small church beside the manor house. Generations of the Ralegh family are commemorated inside the church. The earliest memorial is an effigy of Sir Simon de Ralegh, labelled 1260. There is no written record found at Nettlecombe for Sir Simon de Ralegh in the family history. Sir Simon's effigy is dated 1260, which predates the first recorded rector of Nettlecombe by 37 years, owing to the gap in recording the earliest Ralegh names at the church of Nettlecombe Court. That rector was Will de Locombe (presumably a native of Luccombe, on the edge of Exmoor). A later generation of Raleghs are commemorated by the effigies of Sir John de Ralegh and his first wife, Maud, dated to 1360.

The last Ralegh owner of Nettlecombe Court was another Sir Simon, who died in 1440 and left the estate to his nephew Thomas Whalesborough. Sir Simon left money in his will to build a chantry chapel in St Mary's Church, including a perpetual fund for a priest to pray for the souls of the Ralegh family past and present. Work began on the chantry chapel in 1443. (The chantry chapel is now the south aisle.) The first priest was appointed a decade later in 1453. The job description for the priest retained to pray for the souls of the Raleigh family required the following moral virtues; "with owt the company of women and suspect persons' and that he not be 'lecherous or perjured, a theaff, a murderer or with any other vices corrupt." Sir Walter Raleigh, who descends from the Ralegh men of Nettlecombe, wrote of visiting Nettlecombe Court to visit his cousins and pay respect to his Ralegh ancestors in Nettlecomb's church.

Trevillian-Trevelyan: A family lineage published in Nettlecombe Court shows that the estate passed into the Trevillian family in 1452, when the heiress of the estate, Elizabeth Whalesburgh, upon her marriage, gave Nettlecombe Court as a wedding present to her bridegroom, a knight companion of the king: Sir John Trevilian,[14] Esquire of the Kynge's Body to Henry VI, Gentleman Usher of the King's Chamber.[15] He also served as a member of parliament representing Somerset[16] and as High Sheriff of Cornwall.[17] In the 17th century, the spelling of Trevilian became variably spelt as Trevelyan.

Oldest British hallmarked church plate: Sir John Trevillian was active in the Tudor courts of King Henry VI and Henry VII and had to be pardoned four times by the two different monarchs. In gratitude for the first three of these royal pardons, Trevillian gave a chalice and patten to Nettlecombe's St Mary's Church. These gifts are the oldest examples of British hallmarked church plate in the United Kingdom, and today are preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[18]

During Trevillian's lifetime, probably in 1458, the octagonal Tudor font was beautifully carved for the church at Nettlecombe. Around 1500, a later John Trevillian built the west bell tower. At the west end of the nave is a carved wooden screen bearing his arms and the arms of the family of his wife Jane.

In 1530 Trevillian renovated and built the present Nettlecombe Court, as it generally appears now, incorporating favorite parts of the earlier medieval manor house. Around the same time, the church porch and north aisle were built, followed by the Trevillian Chapel; with the font carvings plastered around 1548.

Nettlecombe set on fire: Nettlecombe Court endured turbulent times during the Reformation and English Civil War. The Trevillian family remained Catholic and loyal to King Charles I, even after the king was beheaded. The family's Royalist stance led to Nettlecombe Court being set on fire in 1645 by the rector of Nettlecombe Court's St Mary's Church. Nettlecombe's rector and parishioners objected to Trevillian's refusal to convert to the Church of England. The rector was joined by his parishioners in setting Nettlecombe ablaze whereby the fire severely damaged the Great Hall of Nettlecombe Court. Nonetheless, Trevillian remained a loyalist, and instead of converting he built a private chapel at Nettlecombe Court with a secret priest's hiding place to provide sanctuary for visiting Catholic priests.[18]

Nettlecombe Court's hidden treasure during the English Civil War: Colonel George Trevelyan then took up arms and fought for the Royalist cause in defense of the king, but eventually was captured and imprisoned by Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell's roundheads came to Nettlecombe to seize whatever property they could: crops, horses, farm animals, wagons, tools, weapons, house goods, etc. In an attempt to protect the family fortune; George's wife, Margaret, hid the family silver and other valuables under floorboards at Nettlecombe, but she died before she could reveal the fortune's whereabouts to her husband. The hidden treasure was not rediscovered until the 1790s. When Cromwell's Parliament demanded excessive war reparations of royalist Catholics, Lady Margaret Trevillian (née Strode) bravely journeyed to London. Lady Trevillian petitioned Parliament, asking them to reduce the too-great burden of war reparations Parliament had assessed upon Nettlecombe Court due to the royalist loyalties of the Tevillian family. Parliament refused Lady Trevillian's request. On her journey home, Lady Trevillian died en route, after catching smallpox whilst in London, leaving her 9 children motherless. Thus the whereabouts of the family jewels and silver lay hidden for more than a century under floorboards at Nettlecombe until by serendipity a maidservant dropped a half-gold needle through a loose floor plank which had to be pulled up to retrieve it, revealing the long hidden valuables.

Baronet: The surviving Trevillian family remained royalists at Nettlecombe; and upon the Restoration of the monarchy under Charles II, George Trevillian was awarded a second baronet by the king for his loyalty with the spelling of the family name changed to Trevelyan to distinguish from their earlier ancestral baronet name of Trevillian. However, the Church of England later became the fixed faith of the land and Catholicism banned. A later generation of Trevillian-Trevelyans headed off further turmoil at Nettlecombe Court by converting to the Church of England in 1787.[18]

Nettlecombe's St Mary's Church: The story of the Court and its church and families, continued to go hand in hand. The church was restored from 1858 when a clerestory was inserted. In 1935 the 13th-century marble altar stone was discovered buried in the churchyard. It was returned to its place inside the church. Other historical highlights of Nettlecombe include an ancient medieval parish chest and several heraldic medieval tiles. There is a marble wall tablet to one Lady Trevillan, who died in 1697, and a tomb slab in the south aisle to a Sir John Trevelyan (d. 1623). Under the west tower is a grave slab to Richard Musgrave (d 1686). The rood screen dates to the late 15th century, with Victorian restoration, and there are several 16th-century carved bench ends. The beautifully carved pulpit dates to the late 17th century, and there is some very good 17th-century glass including several heraldic panels.

Intellectual salon

[edit]In the 19th century, Lady Trevelyan made use of the family estates Wallington and Nettlecombe with its great house and 20,000 acres of land, to host a sophisticated intellectual and artistic salon of the day, renowned for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.[19] The sister of Lord Thomas Macaulay, eminent British historian as author of the History of England, Hannah Macaulay, married into the Trevelyan family resulting in another eminent historian George Macaulay Trevelyan, whose ancestors lived at Nettlecombe.[20][21]

Arms and legend

[edit]

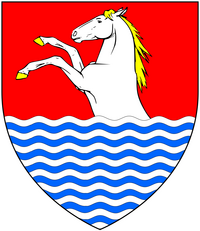

Nettlecombe Court has several emblems and carvings bearing the image of a horse rising from the sea, which are the Trevilian family arms, found throughout the house. The source story of the arms is the Lyonesse legend of Trevilian, as follows: Lyonesse were the lands, now submerged, on the west coast that was said to be the lands of Camelot of King Arthur and the site of the final mortal battle between King Arthur and Mordred. Tennyson's Idylls of the King claims Lyonesse as the final resting place of King Arthur himself. Perhaps this is why the grave of the king cannot be found, as it lies beneath the sea. Roman writings also speak of a Leonis, now submerged off the coast. Lyonesse was also the home of Tristan and Isolde. Legend relates that when Lyonesse suddenly sank, it was inundated as sea levels rushed in. The sole surviving knight of King Arthur's Lyonesse was said to be only one knight, Trevilian, who escaped by riding his white horse through the rising waters to higher ground before Lyonesse was submerged. Trevilian urged the other knights to join him in his attempt to escape, who counter-urged Trevilian to stay put and wait for the floodwaters to pass. The sedentary knights jovially bet wagers amongst themselves around the supper table, as to whether or not Trevilian and his white horse could survive swimming through the incoming flooding and make it to higher ground. None of the other Arthurian knights of Lyonesse, except Trevilian, was said to have survived the great sinking and inundation of Lyonesse.[22] Submerged Medieval church bells of the lost land of Lyonesse were later said to be heard ringing, muffled under the water, when turbulent storms created rough seas. The surviving Trevilian became the founder of the current British Trevilian-Trevelyan family, whose coat of arms still bears a white horse issuing forth from the sea. In some cases the Trevilian white horse arms may be seen combined at Nettlecombe with other related family arms, indicating marriages to Raleigh, Luttrell, Wyndham, Chichester and Strode.

Park

[edit]| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

| Location | Somerset |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | ST055375 |

| Interest | Biological |

| Area | 90.4 hectare (223.4 acre) |

| Notification | 1990 |

| Location map | English Nature |

Nettlecombe Park is important for its lichen flora.[23] Records suggest this site has been wood pasture or parkland for at least 400 years. There are some very old oak pollards which may be of this age or older. The oldest standard trees are over 200 years of age. The continuity of open woodland and parkland, with large mature and over-mature timber, has enabled characteristic species of epiphytic lichens and beetles to become established and persist. Many of the species in the park are now nationally scarce because this type of habitat has been eliminated over large areas of Great Britain. The park was notified as an SSSI in 1990.[24]

Nettlecombe is known to have had a deer park by 1532. In 1556 it covered 80 acres (32 ha) and in 1619 70 acres (28 ha).[25] In the 1690s large areas of parkland were enclosed and four new gardens created, including a water garden, which has now disappeared but is remembered in the name 'Canal Field'.[26] The park was extended in the 18th century which included the removal of the houses that made up the village. In 1792 Thomas Veitch laid out the landscape in the style of Capability Brown including the construction of a Ha-ha between the deer park and the meadows.[27] This included the removal of cottages and relocation of the residents.[23] The parkland is now listed, Grade II, on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of special historic interest in England.[28]

Within the grounds is the Church of St Mary the Virgin which is also a Grade I listed building.[29]

Oak trees

[edit]

Nettlecombe Park is 223 acres (90 ha) of undulating parkland boasting monumental solitary trees and treegroups. It was probably once an oak forest in the main. Today, among these, oaks and sweet chestnuts are still the most common. Several sessile oaks are outstandingly large and were famous from ancient accounts for their great size. Nettlecombe oaks once provided tall strong trees for shipbuilding. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, timber hewn from the oaks of Nettlecombe were hand-selected to help build the ships of the English fleet commanded by Sir Walter Raleigh that defeated the Spanish Armada.[30][31] A number of other English ships that sailed the world to establish British colonies, its navy, and trading empire were built making use of prime Nettlecombe oaks. In the 19th century very good prices were offered to the Trevelyan baronet to cut down and sell the great oaks, but the owner left them standing and the trees have been protected ever since. Some have now grown to a girth of 23 feet (7.0 m).[32] Today, Nettlecombe acorns are sold to nurseries to begin new sapling oak trees.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Historic England. "Leonard Wills Field Centre (formerly listed as Nettlecombe Court) (1173856)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ^ Historic England. "Nettlecombe Court (1001152)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1960). The concise Oxford dictionary of English place-names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 338–339. ISBN 0-19-869103-3.

- ^ Bush, R.J.E (1970). "Nettlecombe Court" (PDF). Field Studies. 3: 275–287. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ R.W. Dunning (editor), A.P. Baggs, R.J.E. Bush, M.C. Siraut (1985). "Parishes: Nettlecombe". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 5. Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nettlecombe Court, (also known as The Leonard Wills Field Centre), Minehead, England". Parks and Gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Nettlecombe Court". Field Studies Council. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Leonard Wills Field Centre (1173856)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Holt, Alan L. (1984). West Somerset: Romantic Routes and Mysterious Byways. Skilton. p. 56. ISBN 978-0284986917.

- ^ "Nettlecombe Court". Exmoor National Park. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Boeringer, James (1989). Organa Britannica: Organs in Great Britain 1660-1860 : a Complete Edition of the Sperling Notebooks and Drawings in the Library of the Royal College of Organists, Volume 1. Bucknell University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780838718940. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Loosemore, W.R. "Loosemore of Devon — Chapter 6". Loosemore of Devon. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Michael I. (2016). The Chamber Organ in Britain 1600 – 1830 (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 978-1138275805.

- ^ R.W. Dunning (editor), A.P. Baggs, R.J.E. Bush, M.C. Siraut (1985). "Parishes: Nettlecombe". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 5. Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Trevelyans and Nettlecombe Court". Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "TREVELYAN, Sir John, 2nd Bt. (1670-1755), of Nettlecombe, Som". The History of Parliament Trust. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Hitchins, Fortescue (1824). The History of Cornwall: From the Earliest Records and Traditions, to the Present Time, Volume 2. Penaluna. pp. 152–153. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "Nettlecombe, Somerset, St Mary's Church | History, Photos, & Visiting Information". Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Walter Calverley Trevelyan Papers". Archives hub. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Vincent, John (19 June 1980). "G.M. Trevelyan's Two Terrible Things". London Review of Books. 2 (12): 3–5. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Trevelyan Family Papers". Archives Hub. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Myss, Caroline. "A Message From Caroline Myss". Myss.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ a b Rose, Francis; Wolsley, Pat (1984). "Nettlecombe Park — its history and its epiphytic lichens: an attempt at correlation" (PDF). Filed Studies. 6: 117–148. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Nettlecombe Park" (PDF). English Nature. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2006. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- ^ Bond, James (1998). Somerset parks and gardens. Tiverton: Somerset Books. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-86183-465-8.

- ^ Bond, James (1998). Somerset parks and gardens. Tiverton: Somerset Books. p. 69. ISBN 0-86183-465-8.

- ^ Bond, James (1998). Somerset parks and gardens. Tiverton: Somerset Books. pp. 93–96, 117. ISBN 0-86183-465-8.

- ^ Historic England. "Nettlecombe Court (1001152)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Mary the Virgin (1173837)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ^ "Francis Trevilian of Nettlecombe Court, 1642". Geni.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Somerset collector squirrels away 10 million acorns". BBC News. 17 October 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Bond, James (1998). Somerset parks and gardens. Tiverton: Somerset Books. p. 93. ISBN 0-86183-465-8.

- ^ "UK acorn picker is responsible for 10 MILLION oak trees". SWNS. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rose, Francis; Wolseley, Pat (1984). Nettlecombe Park: Its History and Its Epiphytic Lichens — An Attempt at Correlation. Field Studies Council. ISBN 1-85153-165-3.

External links

[edit]- Tourist attractions in Somerset

- Country houses in Somerset

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Somerset

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest notified in 1990

- Grade I listed buildings in West Somerset

- Exmoor

- Grade I listed houses in Somerset

- Field studies centres in the United Kingdom

- Grade II listed parks and gardens in Somerset

- Gardens in Somerset