Leo Frobenius

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Leo Frobenius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 June 1873 |

| Died | 9 August 1938 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | German |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ethnology |

Leo Viktor Frobenius (29 June 1873 – 9 August 1938) was a German self-taught ethnologist and archaeologist and a major figure in German ethnography.

Life

[edit]

He was born in Berlin as the son of a Prussian officer and died in Biganzolo, Lago Maggiore, Piedmont, Italy. He undertook his first expedition to Africa in 1904 to the Kasai district in Congo, formulating the African Atlantis theory during his travels.

During World War I, between 1916 and 1917, Leo Frobenius spent almost an entire year in Romania, travelling with the German Army for scientific purposes. His team performed archaeological and ethnographic studies in the country, as well as documenting the day-to-day life of the ethnically diverse inmates of the Slobozia prisoner camp. Numerous photographic and drawing evidences of this period exist in the image archive of the Frobenius Institute.[1]

Until 1918 he travelled in the western and central Sudan, and in northern and northeastern Africa. In 1920 he founded the Institute for Cultural Morphology in Munich.

Frobenius taught at the University of Frankfurt. In 1925, the city acquired his collection of about 4700 prehistorical African stone paintings, kept at the University's institute of ethnology, which was named the Frobenius Institute in his honour in 1946.

In 1932 he became honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt, and in 1935 director of the municipal ethnographic museum.

Theories

[edit]Frobenius was influenced by Richard Andree, and his own teacher Friedrich Ratzel.[2]

In 1897/1898 Frobenius defined several "culture circles" (Kulturkreise), cultures showing similar traits that have been spread by diffusion or invasion. Bernhard Ankermann was also influential in this area.[3]

A meeting of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory was held on November 19, 1904, which was to become historical. On this occasion Fritz Graebner read a paper on "Cultural cycles and cultural strata in Oceania", and Bernhard Ankermann lectured on "Cultural cycles and cultural strata in Africa". Even today these lectures by two assistants of the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin are frequently considered the beginning of research on cultural history, although in fact Frobenius' book "Der Ursprung der afrikanischen Kulturen" could claim this honour for itself.[4]

With his term paideuma, Frobenius wanted to describe a gestalt, a manner of creating meaning (Sinnstiftung), that was typical of certain economic structures. Thus, the Frankfurt cultural morphologists tried to reconstruct "the" world-view of hunters, early planters, and megalith-builders or sacred kings. This concept of culture as a living organism was continued by his most devoted disciple, Adolf Ellegard Jensen, who applied it to his ethnological studies.[5] It also later influenced the theories of Oswald Spengler.[6]

His writings with Douglas Fox were a channel through which some African traditional storytelling and epic entered European literature. This applies in particular to Gassire's lute, an epic from West Africa which Frobenius had encountered in Mali. Ezra Pound corresponded with Frobenius from the 1920s, initially on economic topics. The story made its way into Pound's Cantos through this connection.

In the 1930s, Frobenius claimed that he had found proof of the existence of the lost continent of Atlantis.[7]

African Atlantis

[edit]

"African Atlantis" is a hypothetical civilization thought to have once existed in northern Africa, proposed by Leo Frobenius around 1904.[8] Named after the mythical Atlantis, this lost civilization was conceived as the root of African culture and social structure. Frobenius surmised that a white civilization must have existed in Africa prior to the arrival of the European colonisers, and that it was this white residue that enabled native Africans to exhibit traits of military power, political leadership and... monumental architecture.[8] Frobenius's racist theory stated that historical contact with immigrant whites of Mediterranean origin was responsible for advanced native African culture. He stated that such a civilization must have disappeared long ago, to allow for the perceived dilution of their civilization to the levels that were encountered during the period.[8]

Legacy

[edit]Due to his studies in African history, Frobenius remains a figure of renown in many African countries. In particular, he influenced Léopold Sédar Senghor, one of the founders of Négritude, who once claimed that Frobenius had "given Africa back its dignity and identity." Aimé Césaire quoted Frobenius as praising African people "civilized to the marrow of their bones"(Discourse on Colonialism), instead of the degrading vision encouraged by colonial propaganda.

On the other hand, Wole Soyinka, in his 1986 Nobel Lecture, criticized Frobenius for his "schizophrenic" view comparing Yoruba art and artists.[9] Quoting Frobenius's statement that "I was moved to silent melancholy at the thought that this assembly of degenerate and feeble-minded posterity should be the legitimate guardians of so much loveliness," Soyinka called such sentiments "a direct invitation to a free-for-all race for dispossession, justified on the grounds of the keeper's unworthiness."

Otto Rank relied on Frobenius' reports of the Fanany burial in Madagascar to develop his idea of macrocosm and microcosm in his book Art and Artist (Kunst und Künstler [1932])

"Certainly the idea of the womb as an animal has been widespread among different races of all ages, and it 'furnishes an explanation of (for instance) the second burial custom discovered by Frobenius along with the Fanany burial in South Africa.[a] This consisted in placing the dead king's body in an artificially emptied bull's skin in such a manner that the appearance of life was achieved. This bull-rite was undoubtedly connected with the moon-cult (compare mooncalf) and belongs therefore to the maternal culture-stage, at which the rebirth idea also made use of maternal animal symbols, the larger mammals being chosen. Yet the "mother's womb symbolism" denotes more than the mere repetition of a person's own birth: it stands for the overcoming of human mortality by assimilation to the moon's immortality. This sewing-up of the dead in the animal skin has its mythical counterpart in the swallowing of the living by a dangerous animal, out of which he escapes by a miracle. Following an ancient microcosmic symbolism, Anaximander compared the mother's womb with the shark. This conception is later found in religious form as the Jonah myth, and also appears in a cosmological adaptation in the whale myths collected in Oceania by Frobenius. Hence, the frequent suggestion that the seat of the soul after death (macrocosmic underworld) is in the belly of an animal (fish, dragon). The fact that in these traditions the animals are always those dangerous to man indicates that the animal womb is regarded not only as the scene of a potential rebirth but also as that of a dreaded mortality, and it is this which led to all the cosmic assimilations to the immortal stars."

Frobenius also confirmed the role of the moon cult in African cultures, according to Rank:

"Bachofen [Johann Jakob Bachofen (1815-1887)] was the first to point out this connexion in the ancient primitive cultures in his Mutterrecht, but it has since received widespread corroboration from later researchers, in particular Frobenius, who discovered traces of a matriarchal culture in prehistoric Africa (Das unbekannte Afrika, Munich, 1923)."

Frobenius' work gave Rank insight into the double meaning of the king's ritual murder, and the cultural development of soul belief:

"Certain African traditions (Frobenius: Erythraa) lead to the assumption that the emphasizing of one or another of the inherent tendencies of the ritual was influenced by the character of the slain king, who in one case may have been feared and in another wanted back again."

"The Fanany myth, mentioned below, of the Betsileo in Madagascar shows already a certain progress from the primitive worm to the soul-animal.[10] The Betsileo squeeze the putrefying liquid out of the bodies of the dead at the feet and catch it in a small jar. After two or three months a worm appears in it and is regarded as the spirit of the dead. This jar is then placed in the grave, where the corpse is laid only after the appearance of the Fanany. A bamboo rod connects the jar with the fresh air (corresponding to the " soulholes" of Northern stone graves). After six to eight months (corresponding possibly to the embryonic period) the Fanany (so the Betsileo believe) then appears in daylight in the form of a lizard. The relatives of the dead receive it with great celebrations and then push it back down the rod in the hope that this ancestral ghost will prosper exceedingly down below and become the powerful protector of the family and, for that matter, the whole village."

"Later totemism- the idea of descent from a definite animal species - seems to emerge only from a secondary interpretation of the soul-worm idea or the soul-animal idea in accordance with a 'law of inversion' (Frobenius) peculiar to mythical thought; just as the myth of the Creation as the projection backward in time of the myth of the end of the world is in itself only a formal expression of the principle of rebirth."

African art taken to Europe

[edit]-

Mask Tyi wara (Mali)

-

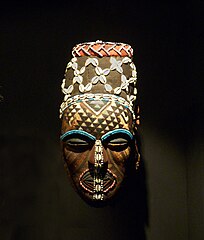

Kuba Mask (Congo)

-

Luba (Congo)

-

Ife (Nigeria)

Works

[edit]

- Die Geheimbünde Afrikas (Hamburg 1894)

- Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis. Petermanns Mitteilungen 43/44, 1897/98

- Weltgeschichte des Krieges (Hannover 1903)

- Das Zeitalter des Sonnengottes. Band 1. Georg Reimer, Berlin 1904.

- Der schwarze Dekameron: Belege und Aktenstücke über Liebe, Witz und Heldentum in Innerafrika (Berlin 1910)

- Und Afrika sprach...

- Band I: Auf den Trümmern des klassischen Atlantis (Berlin 1912) link

- Band II: An der Schwelle des verehrungswürdigen Byzanz (Berlin 1912)

- Band III: Unter den unsträflichen Äthiopen (Berlin 1913)

- Paideuma (München 1921)

- Dokumente zur Kulturphysiognomik. Vom Kulturreich des Festlandes (Berlin 1923)

- Erythräa. Länder und Zeiten des heiligen Königsmordes (Berlin 1931)

- Indische Reise (Berlin 1931)

- Kulturgeschichte Afrikas (Zürich 1933)

- Erlebte Erdteile (unknown location or date)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Although this was actually in Madagascar, during this time period "South Africa" was still synonymous with Southern Africa. See "Greater South Africa" for contemporaneous South African ambitions to expand across the whole region.

References

[edit]- ^ Mihai Dumitru, Leo Frobenius în România Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Diffusionism and Acculturation anthropology.ua.edu

- ^ Frobenius, Leo International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 1968. Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Jürgen Zwernemann, LEO FROBENIUS AND CULTURAL RESEARCH IN AFRICA. Research review--Institute of African studies. 3 (2) 1967, pages 2-20 lib.msu.edu

- ^ Short Portrait: Adolf Ellegaard Jensen

- ^ Leon Surette, The Birth of Modernism, McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, 1994, p. 63.

- ^ "Leo Frobenius", Encyclopædia Britannica, 1960 edition

- ^ a b c Miller, p. 4

- ^ Wole Soyinka (8 December 1986). "This Past Must Address Its Present". Nobel Lecture. Nobelprize.org.

- ^ From Sibree's Madagascar, pp. 309 et seq., quoted by Frobenius in Der Seelenwurm (1895) and reprinted in Erlebte Erdteile, I (Frankfurt, 1925), a treatise which deals principally with the "vase-cult" arising out of the storing of decayed remains in jars (see later remarks on the vase in general).

- Miller, Joseph C. (1999). "History and Africa/Africa and History". The American Historical Review. 104 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2307/2650179. JSTOR 2650179.

- "German Discovers Atlantis In Africa; Leo Frobenius Says Find of Bronze Poseidon Fixes Lost Continent's Place". The New York Times. 30 January 1911.

- Kuba, Richard (2020). “The Expeditions of Leo Frobenius between Science and Politics: Nigeria 1910-1912 ”, in BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology, Paris.

- Ivanoff, Hélène (2020). « Les "compagnons obscurs" des expéditions de Leo Frobenius », in BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology, Paris.

External links

[edit]- Homepage of the Frobenius Institute

- Robert Fisk, The German Lawrence of Arabia had much to live up to – and failed

- Leo Frobenius în România

- Newspaper clippings about Leo Frobenius in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Resources related to research : BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology."Frobenius, Leo (1873-1938)" Paris, 2020. (ISSN 2648-2770)

- Works by Leo Frobenius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)