Lee Krasner

Lee Krasner | |

|---|---|

Krasner in 1983 | |

| Born | Lena Krassner October 27, 1908 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | June 19, 1984 (aged 75) New York City, U.S. |

| Education | Cooper Union National Academy of Design Hans Hofmann |

| Known for | Painting, collage |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism |

| Spouse | |

Lenore "Lee" Krasner (born Lena Krassner; October 27, 1908 – June 19, 1984) was an American painter and visual artist active primarily in New York whose work has been associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement. She received her early academic training at the Women's Art School of Cooper Union, and the National Academy of Design from 1928 to 1932. Krasner's exposure to Post-Impressionism at the newly opened Museum of Modern Art in 1929 led to a sustained interest in modern art. In 1937, she enrolled in classes taught by Hans Hofmann, which led her to integrate influences of Cubism into her paintings. During the Great Depression, Krasner joined the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project, transitioning to war propaganda artworks during the War Services era.

By the 1940s, Krasner was an established figure among the American abstract artists of the New York School,[1] with a network including painters such as Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko. However, Krasner's career was often overshadowed by that of her husband, Jackson Pollock, whom she married in 1945. Their life was marred by Pollock's infidelity and alcoholism, while his untimely death in a drunk-driving incident in 1956 had a deep emotional impact on Krasner.[2][3] The late 1950s to the early 1960s in Krasner's work were characterized by a more expressive and gestural style. In her later years, she received broader artistic and commercial recognition and shifted toward large horizontal paintings marked by hard-edge lines and bright contrasting colors.

During her life, Krasner received numerous honorary degrees, including Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from Stony Brook University. Following Krasner's death in 1984, critic Robert Hughes described her as "the Mother Courage of Abstract Expressionism" and a posthumous retrospective exhibition of her work was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.[4] Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs, New York and the Pollock-Krasner Foundation were established to preserve the work and cultural influence of her and her husband. The latter has since focused on supporting new artists and art historical scholarship in American art.

Early life

[edit]Krasner was born as Lena Krassner (outside the family she was known as Lenore Krasner) on October 27, 1908, in Brooklyn, New York.[5] She was the daughter of Chane (née Weiss) and Joseph Krasner,[6] Russian-Jewish immigrants from Spykov (now Shpykiv, a Jewish community in what is now Ukraine). Krasner's parents were Russian-Jewish immigrants who fled to the United States to escape antisemitism and the Russo-Japanese War,[7] and Chane changed her name to Anna once she arrived.[8] Lee was the youngest of six children, and the only one to be born in the United States.[9]

Education

[edit]From an early age, Krasner knew she wanted to pursue art as a career. Her career as an artist began when she was a teenager. She specifically sought out enrollment at Washington Irving High School for Girls as they offered an art major.[9] After graduating, she attended the Women's Art School of Cooper Union on a scholarship.[10] There, she completed the course work required for a teaching certificate in art.[9] Krasner pursued yet more art education at the National Academy of Design in 1928, completing her course load there in 1932. When Krasner attended high school, she almost didn't graduate based on her grade in art, which was the subject she attended the school for, and was only given 65 to pass the class.[11]

By attending a technical art school, Krasner was able to gain an extensive and thorough artistic education as illustrated through her knowledge of the techniques of the Old Masters.[12] She also became highly skilled in portraying anatomically correct figures.[13] There are relatively few works that survive from this time period apart from a few self-portraits and still lifes because most of the works were burned in a fire. One image that still exists from this period is her "Self Portrait" painted in 1930, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She submitted it to the National Academy in order to enroll in a certain class, but the judges could not believe that the young artist produced a self-portrait en plein air.[12] In it, Krasner depicts herself with a defiant expression surrounded by nature. She also briefly enrolled in the Art Students League of New York in 1928.[14] There, she took a class led by George Bridgman who emphasized the human form.[14][15]

Krasner was highly influenced by the opening of the Museum of Modern Art in 1929. She was very affected by Post-Impressionism and grew critical of the academic notions of style she had learned at the National Academy. In the 1930s, she began studying modern art through learning the components of composition, technique, and theory.[13] She began taking classes from Hans Hofmann in 1937, which modernized her approach to the nude and still life.[15] He emphasized the two-dimensional nature of the picture plane and usage of color to create spatial illusion that was not representative of reality through his lessons.[16] Throughout her classes with Hofmann, Krasner worked in an advanced style of cubism, also known as neo-cubism. During the class, a human nude or a still life setting would be the model from which Krasner and other students would have to work. She typically created charcoal drawings of the human models and oil on paper color studies of the still life settings.[17] She typically illustrated female nudes in a cubist manner with tension achieved through the fragmentation of forms and the opposition of light and dark colors. The still lifes illustrated her interest in fauvism since she suspended brightly colored pigment on white backgrounds.[18]

Hans Hofmann "was very negative" his former student said "but one day he stood before my easel and he gave me the first praise I had ever received as an artist from him. He said, 'This is so good, you would never know it was done by a woman". She also received praise from Piet Mondrian who once told her "You have a very strong inner rhythm; you must never lose it."[citation needed]

Early career

[edit]

Krasner supported herself as a waitress during her studies but it eventually became too difficult due to the Great Depression.[19] In 1935 to continue providing for herself she joined the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project, working in the mural division as an assistant to Max Spivak.[20] Her job was to enlarge other artists' designs for large-scaled public murals. Murals were created to be easily understood and appreciated by the general public; however, the abstract art Krasner produced did not meet this need. Although happy to be employed, she was dissatisfied because she did not enjoy working with the figurative images created by other artists.[19] Throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s, she created gouache sketches in the hopes of one day creating an abstract mural.[21] Soon after one of her proposals for a mural was approved for the WNYC radio station, the Works Progress Administration became War Services and all art had to be created for war propaganda.[20] Krasner continued working for War Services by creating collages for the war effort that were displayed in the windows of nineteen department stores in Brooklyn and Manhattan.[22][23] She was intensively involved with the Artists Union during her employment with the WPA but was one of the first to quit when she realized the communists were taking it over.[20] However, by being part of this organization she was able to meet more artists in the city and enlarge her network.[24]

She joined the American Abstract Artists in 1940. While a member, she typically exhibited cubist still life in a black-gridded cloisonne style that was highly impastoed and gestural.[25] She met future abstract expressionists Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Franz Kline, Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, and Bradley Walker Tomlin through this organization.[26] However, she lost interest in their usage of hard-edge geometric style after beginning her relationship with Jackson Pollock.[27]

Career

[edit]Krasner is identified as an abstract expressionist due to her abstract, gestural, and expressive works in painting, collage painting, charcoal drawing, and occasionally mosaics. She would often cut apart her own drawings and paintings to create her collage paintings. She also commonly revised or completely destroyed an entire series of works due to her critical nature; as a result, her surviving body of work is relatively small. Her catalogue raisonné, published in 1995 by Abrams, lists 599 known pieces.

Her changeable nature is reflected throughout her work, which has led critics and scholars to have different conclusions about her and her oeuvre.[28] Krasner's style often alternates between classic structure and baroque action, open form and hard-edge shape, and bright color and monochrome palette. Throughout her career, she refused to adopt a singular, recognizable style and instead embraced change through varying the mood, subject matter, texture, materials, and compositions of her work often.[10][29] By changing her work style often, she differed from other abstract expressionists since many of them adopted unchanging identities and modes of depiction.[30] Despite these intense variations, her works can typically be recognized through their gestural style, texture, rhythm, and depiction of organic imagery.[10] Krasner's interest in the self, nature, and modern life are themes which commonly surface in her works.[28] She was often reluctant to discuss the iconography of her work and instead emphasized the importance of her biography since she claimed her art was formed through her individual personality and her emotional state.[31]

Early 1940s

[edit]Throughout the first half of the 1940s, Krasner struggled with creating art that satisfied her critical nature. Throughout the 1930s the New York painting scene consisted of a very intimate group of artists that studied each other's efforts but was not yet shown in galleries. The 1940s marked a transition from an "age of innocence" to a modernist mindset of pure expression.[32] She was highly affected by seeing Pollock's work for the first time in 1942, causing her to reject Hofmann's cubist style which required working from a human or still life model. She called the work produced during this frustrating time her "grey slab paintings." She would create these paintings by working on a canvas for months, overpainting, scraping or rubbing paint off, and adding more pigment until the canvas was nearly monochrome from so much paint buildup. She eventually would destroy these works, which is the reason there is only one painting that exists from this time period.[27] Krasner's extensive knowledge of cubism was the source of her creative problem since she needed her work to be more expressive and gestural to be considered contemporary and relevant.[33] In the fall of 1945, Krasner destroyed many of her cubist works she created during her studies with Hofmann, although the majority of paintings created from 1938 to 1943 survived this reevaluation.[34]

Little Images: 1946–1949

[edit]Beginning in 1946, Krasner began working on her Little Image series. Commonly categorized as mosaic, webbed, or hieroglyphs depending on the style of the image,[35] these types of paintings, totalling around 40, she created until 1949.[36] The mosaic images were created through the thick buildup of paint while her webbed paintings were made through a drip technique in which the paintbrush was always close to the surface of the canvas.[37] Since Krasner used a drip technique, many critics believed upon seeing this work for the first time that she was reinterpreting Pollock's chaotic paint splatters.[38][39] Her hieroglyph paintings are gridded and look like an unreadable, personal script of Krasner's creation.[37] These works demonstrate her anti-figurative concerns, allover approach to the canvas, gestural brushwork, and disregard of naturalistic color.[40] They have little variation of hue but are very rich in texture due to the buildup of impasto and also suggest space continuing beyond the canvas.[41][42] These are considered her first successful images that she created while working from her own imagination rather than a model.[43] The relatively small scale of the images can be attributed to the fact she painted them on an easel in her small studio space in an upstairs bedroom at The Springs.[37][41]

Many scholars interpret these images as Krasner's reworking of Hebrew script.[35][44][45] In an interview later in her career, Krasner admitted to subconsciously working from right to left on her canvases, leading scholars to believe that her ethnic and cultural background affected the rendering of her work.[44] Some scholars have interpreted these paintings to represent the artist's reaction to the tragedy of the Holocaust.[35][41][45] Others have claimed that Krasner's work with the War Services project caused her to be interested in text and codes since cryptoanalysis was a main concern for winning the war.[46]

When she completed the Little Image series in 1949, Krasner again went through a critical phase with her work. She tried out and rejected many new styles and eventually destroyed most of the work she made in the early 1950s.[47] There is evidence that she began experimenting with automatic painting and created black-and-white, hybridized, monstrous figures on large canvases in 1950.[48] These were the paintings that Betty Parsons saw when she visited The Springs that summer, causing the gallerist to offer Krasner a show in the fall.[48] Between the summer and the fall, Krasner again had shifted her style to color field painting and destroyed the figurative automatic paintings she made. The Betty Parsons show was Krasner's first solo exhibition since 1945.[49] After the exhibition, Krasner used the color field paintings to make her collage paintings.

Early collage images: 1951–1955

[edit]By 1951, Krasner had started her first series of collage paintings. To create them, Krasner pasted cut-and-torn shapes onto all but two of the large-scale color field paintings she created for the Betty Parsons exhibition in 1951.[50] This period marks the time when the artist stopped working on an easel since she created these works by lying the support on the floor.[51] To make these images, she would pin the separate pieces to a canvas and modify the composition until she was satisfied. She then would paste the fragments on the canvas and add color with a brush when desired.[52] Most of the collage paintings she created recall plant or organic forms but do not completely resemble a living organism.[53] By using many different materials, she was able to create texture and prevent the image from being entirely flat.[50] The act of tearing and cutting elements for the collage embodies Krasner's expression since these acts are aggressive.[54] She explored contrasts of light and dark colors, hard and soft lines, organic and geometric shapes, and structure and improvisation through this work.[55] These collage paintings represent Krasner's turn away from nonobjective abstraction. From this period onwards, she created metaphorical and content-laden art which alludes to organic figures or landscapes.[51]

From 1951 to 1953, most of her works were made from ripped drawings completed in black ink or wash in a figurative manner. By ripping the paper instead of cutting it, the edges of the figures are much more soft in comparison to the geometric and hard-edged shapes in her previous works.[54] From 1953 to 1954, she created smaller-sized collage paintings that were composed of fragments of undesired works.[56] Some of the discarded works she used were splatter paintings completed by Pollock. Many scholars have expressed different interpretations about why she used her partner's unwanted canvases. Some assert that she simultaneously demonstrated her admiration for his art while also recontextualizing his aggressive physicality through manipulating his images into a collage form.[28][57] Others believe that she was creating a sense of intimacy between themselves, which was lacking in their actual relationship by this time period, by combining their works together.[58] By 1955, she made collage paintings on a larger scale and varied the material she used for the support, using either masonite, wood, or canvas.[51] These works were first exhibited by Eleanor Ward at the Stable Gallery in 1955 in New York City, but they received little public acclaim apart from a good review from Clement Greenberg.[53][59]

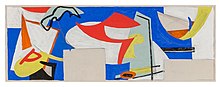

Earth Green Series: 1956–1959

[edit]During the summer of 1956, Krasner started her Earth Green Series. While she started making this work before Pollock's death, they are considered to reflect her feelings of anger, guilt, pain, and loss she experienced about their relationship before and after he died.[60] The intense emotion she felt during this time caused her art to develop along more liberated lines of her self-expression and pushed the boundaries of conventional, developed concepts of art.[61] Through these large-scale action paintings, Krasner depicts hybridized figures that are made up of organic plant-like forms and anatomical parts, which often allude to both male and female body parts.[60] These forms dominate the canvas, causing it to be crowded and densely-packed with bursting and bulging shapes. The pain she experienced during this period is illustrated through the principal usage of flesh tones with blood-red accents in the figures which suggest wounds. The paint drips on her canvas show her speed and willingness to relinquish absolute control, both necessary for portraying her emotions.[62]

By 1957, Krasner continued to create figurative abstract forms in her work, but they suggest more floral elements rather than anatomical. She used brighter colors which were more vibrant and commonly contrasted other colors in the composition. She also would dilute paint or use a dry brush to make the colors more transparent.[63]

In 1958, Krasner was commissioned to create two abstract murals for an office building at 2 Broadway in Manhattan. According to the American art historian Barbara Rose, working on the collage maquettes in preparation for the murals provided Krasner "with a means of translating her winged, floral, and organic forms into monumental abstractions on a public scale".[64]

Umber Series: 1959–1961

[edit]Krasner's Umber Series paintings were created during a time when the artist was suffering from insomnia. Since she was working during the night, she had to paint with artificial light rather than daylight, causing her palette to shift from bright, vibrant hues to dull, monochrome colors.[65] She also was still dealing with the death of Pollock and the recent death of her mother, which led her to use an aggressive style when creating these images.[66] These mural-sized action paintings contrast dark and light severely since white, grays, black, and brown are the predominant colors used.[67] Evidence of her animated brushwork can be seen through the drips and splatters of paint on the canvas. There is no central spot for the viewer to focus on in these works, making the composition highly dynamic and rhythmic.[67] To paint on such a large scale, Krasner would tack the canvas to a wall.[65] These images no longer implied organic forms but instead are often interpreted as violent and turbulent landscapes.[68]

Primary Series: 1960s

[edit]By 1962, she begins using bright colors and allude to floral and plant-like shapes.[69] These works are compositionally similar to her monochrome images due to their large size and rhythmic nature with no central focal point.[70] Their palettes often contrast with one another and allude to tropical landscapes or plants.[71] She continued working in this style until she suffered an aneurysm, fell, and broke her right wrist in 1963.[70][72] Since she still wanted to work, she began painting with her left hand. To overcome working with her non-dominant hand, she often would directly apply paint from a tube to the canvas rather than using a brush, causing there to be large patches of white canvas on the surfaces of the images. The gesture and the physicality of these works is more restrained.[70]

After recovering from her broken arm, Krasner began working on bright and decorative allover painting which are less aggressive than her Earth Green and Umber Series paintings. Often, these images recall calligraphy or floral ornamentation not blatantly related to Krasner's known emotional state.[73] Floral or calligraphic shapes dominate the canvas, connecting variable brushwork into a single pattern.[74]

By the second half of the 1960s, critics began reassessing Krasner's role in the New York School as a painter and critic who greatly influenced Pollock and Greenberg.[75][76][77] Prior to this, her status as an artist was typically overlooked by critics and scholars due to her relationship with Pollock.[75] Since he served as such a large figure in the abstract expressionist movement, it is still often difficult for scholars to discuss her work without mentioning Pollock in some capacity.[78] This reevaluation is reflected in her first retrospective exhibition of her paintings which was held in London at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1965. This exhibition was more well-received by critics in comparison to her previous shows in New York.[75][77]

In 1969, Krasner mostly concentrated on creating works on paper with gouache. These works were named either Earth, Water, Seed, or Hieroglyphics and often looked similar to a Rorschach test. Some scholars claim that these images were a critique of Greenberg's theory about the importance of the two-dimensional nature of the canvas.[79]

Late career

[edit]

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the painter's work was significantly influenced by postmodern art and emphasized the inherent problems of art as a form of communication.[80]

Starting in 1970, Krasner began making large horizontal paintings made up of hard-edge lines and a palette of a few bright colors that contrasted one another.[81] She painted in this style until about 1973. Three years later, she started working on her second series of collage images. She began working on these after cleaning out her studio and discovered some charcoal drawings mostly of figure studies that she completed from 1937 to 1940. After saving a few, Krasner decided to use the rest in a new series of collages. In this work, the black and gray shapes of the figure studies are juxtaposed against the blank canvas or the addition of brightly colored paint.[79] The hard-edged shapes of the cut drawings are reconstructed into curvilinear shapes that recall floral patterns. Texture is induced through the contrast of the smooth paper and rough canvas.[82] Since the figure studies are cut up and rearranged without consideration of their original intention or message, the differences between the old drawings and new structures are highly exaggerated.[83] All of the collages' titles from this series are different verb tenses interpreted as a critique of Greenberg's and Michael Fried's insistence on the presentness of modern art.[84] This series was very well received by a large audience when they were exhibited in 1977 at the Pace Gallery. It is also considered a statement about how artists need to reexamine and rework their style in order to stay relevant as they grow older.[85]

Krasner and Pollock's mutual influence on one another

[edit]Although many people believe that Krasner stopped working in the 1940s in order to nurture Pollock's home life and career, she never in fact stopped creating art.[10] While their relationship developed, she shifted her focus from her own to Pollock's art in order to help him gain more recognition due to the fact that she believed that he had "much more to give with his art than she had with hers".[86]

Throughout her career, Krasner went through periods of struggle where she would experiment with new styles that would satisfy her means for expression and harshly critique, revise, or destroy the work she would produce. Because of this self-criticism, there are periods of time where little to none of her work exists, specifically the late 1940s and early 1950s.[10]

Krasner and Pollock both had an immense effect on each other's artistic styles and careers. Since Krasner had learned from Hans Hofmann while Pollock received training from Thomas Hart Benton, each took different approaches to their work. Krasner learned from Hofmann the importance of the abstracting from nature and emphasizing the flat nature of the canvas while Pollock's training highlighted the importance of complex design from automatic drawing. Krasner's extensive knowledge of modern art helped Pollock since she brought him up to date with what contemporary art should be. He was therefore able to make works that were more organized and cosmopolitan. Additionally, Krasner was responsible for introducing Pollock to many artists, collectors, and critics who appreciated abstract art such as Willem de Kooning, Peggy Guggenheim, and Clement Greenberg. Through her friendship with collector and artist Alfonso Ossorio, Pollock also became acquainted with Ossorio and Joseph Glasco.[87] Pollock helped Krasner become less restrained when making her work. He inspired her to stop painting from human and still life models in order to free her interior emotions and become more spontaneous and gestural through her work.[88]

Krasner struggled with the public's reception of her identity, both as a woman and as Pollock's wife. When they both exhibited in a show called "Artists: Man and Wife" in 1949, an ARTnews reviewer stated: "There is a tendency among some of these wives to 'tidy up' their husband's styles. Lee Krasner (Mrs. Jackson Pollock) takes her husband's paint and enamels and changes his unrestrained, sweeping lines into neat little squares and triangles."[89] Even after the rise of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s, Krasner's artistic career was always put into relation to Pollock since remarks made about her work often commented on how she had become a successful artist by moving out of Pollock's shadow.[90] In articles about her work, Pollock is continually referred to. Krasner is still sometimes referred to as "Action Widow", a term coined in 1972 by art critic B. H. Friedman who accused the female surviving partners of Abstract Expressionist artists of artistic dependence on their male partners.[91] Typically in the 1940s and 1950s, Krasner also would not sign works at all, sign with the genderless initials "L.K.", or blend her signature into the painting in order to not emphasize her status as a woman and as a wife to another painter.[92]

Legacy

[edit]

Mary Beth Edelson's Some Living American Women Artists / Last Supper (1972) appropriated Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, with the heads of notable women artists, including Krasner's, collaged over the heads of Christ and his apostles. The image, addressing the role of religious and art historical iconography in the subordination of women, became "one of the most iconic images of the feminist art movement."[93][94]

Krasner died on June 19, 1984, age 75, at New York Hospital. Krasner led a successful commercial career and was in charge of her husband's estate, and at the time of her death, her estate was worth over $20 million.[95]

Six months after her death, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City held a retrospective exhibition of her work. A review in The New York Times noted that it "clearly defines Krasner's place in the New York School" and that she "is a major, independent artist of the pioneer Abstract Expressionist generation, whose stirring work ranks high among that produced here in the last half-century."[96] As of 2008, Krasner is one of only four women artists to have had a retrospective show at this institution. The other three women are Louise Bourgeois (1982), Helen Frankenthaler (1989) and Elizabeth Murray (2004).[97]

Her papers were donated to the Archives of American Art in 1985; they were digitized and posted on the web for researchers.[98]

After her death, her East Hampton property became the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio, and is open to the public for tours. A separate organization, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, was established in 1985. The Foundation functions as the official estate for both Krasner and Pollock, and also, under the terms of her will, serves "to assist individual working artists of merit with financial need."[99] The U.S. copyright representative for the Pollock-Krasner Foundation is the Artists Rights Society.[100]

On November 11, 2003, Celebration, a large painting from 1960 sold to the Cleveland Museum of Art for $1.9 million and in May 2008, Polar Stampede sold for $3.2 million. "No one today could persist in calling her a peripheral talent," said critic Robert Hughes.[101]

In 2016 her work was included in the exhibition Women of Abstract Expressionism organized by the Denver Art Museum.[102]

In 2017 Krasner was one of the subjects of the book Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art by Mary Gabriel.[103]

In 2023 her work was included in the exhibition Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.[104]

In popular culture

[edit]Krasner was portrayed by Marcia Gay Harden in the film Pollock (2000), which is about the life of her husband Jackson Pollock. Harden won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in the film.

In John Updike's novel Seek My Face (2002), a significant portion of the main character's life is based on Krasner's.

Personal life

[edit]Relationship with Jackson Pollock

[edit]Krasner and Jackson Pollock established a relationship in 1942 after they both exhibited at the McMillen Gallery. She was intrigued by his work and the fact she did not know who he was even though she knew many abstract painters in New York. She went to his apartment to meet him.[23][105] By 1945, they moved to The Springs on the outskirts of East Hampton, New York. In the summer of that year, they got married in a church with two witnesses.[106]

While the two lived in the farmhouse in The Springs, they continued creating art. They worked in separate studio spaces with Krasner in an upstairs bedroom in the house while Pollock worked in the barn in their backyard. When not working, the two spent their time cooking, baking, gardening, keeping the house organized, and entertaining friends.[107]

By 1956, their relationship became strained as they faced certain issues. Pollock had begun struggling with his alcoholism and was having an extramarital affair with Ruth Kligman. Krasner left in the summertime to visit friends in Europe but had to quickly return when Pollock died in a car crash while she was away.[108]

Religion

[edit]Krasner was brought up in an orthodox Jewish home throughout her childhood and adolescence. Her family lived in Brownsville, Brooklyn, which had a large population of poor Jewish immigrants. Her father spent most of his time practicing Judaism, and her mother kept up the household and the family business.[109] Krasner appreciated aspects of Judaism like Hebrew script, prayers, and religious stories.

As a teenager, she grew critical of what she perceived as misogyny in orthodox Judaism. In an interview later in her life, Krasner recalls reading a prayer translation and thinking it was "indeed a beautiful prayer in every sense except for the closing of it...if you are a male you say, 'Thank You, O Lord, for creating me in Your image'; and if you are a woman you say, 'Thank You, O Lord, for creating me as You saw fit.'"[110] She also began reading existentialist philosophies during this time period, causing her to turn from Judaism even further.[111]

While she married Pollock in a church, Krasner continued to identify herself as Jewish but decided to not practice the religion. Her identity as a Jewish woman has affected how scholars interpret the meaning of her art.[111]

Some institutional holdings

[edit]The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- Self Portrait, 1929[112]

- Gansevoort, Number 1, 1934[113]

- Night Creatures, 1965[114]

- Rising Green, 1972[115]

The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

- Still Life, 1938[116]

- Seated Nude, 1940[117]

- Untitled, 1949[118]

- Number 3 (Untitled), 1951[119]

- Untitled, 1964[120]

- Gaea, 1966[121]

Other institutions:

- Composition, 1949, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia[122]

- Untitled, 1953, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra[123]

- Milkweed, 1955, Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, New York[124]

- Polar Stampede, 1961, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art[125]

- Gold Stone, 1969, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco[126]

- Comet, 1970, Robert Miller (art dealer) Gallery, New York City[127]

- Imperative, 1976, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.[128]

- Primary Series, Blue Stone, pre-1982, University of Wisconsin–Stout Furlong Gallery, Menomonie, Wisconsin[129]

Art market

[edit]At a 2003 Christie's auction in New York, Lee Krasner's horizontal composition in oil on canvas, Celebration (1960), multiplied its presale estimate more than fourfold as it ended its upward course at $1.9 million.[130] In 2019, Sotheby's set a new auction record for Krasner when The Eye is the First Circle (1960) sold for $10 million to Robert Mnuchin.[131]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nemser, Cindy (December 1, 1973). "Lee Krasner's Paintings, 1946–49". Artforum. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

Lee Krasner is a vital and influential member of the first generation of the New York School.

- ^ Cooke, Rachel (May 12, 2019). "Reframing Lee Krasner, the artist formerly known as Mrs Pollock". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

Pollock was killed in a car accident, having taken the wheel while drunk, in 1956, at the age of 44. Though he and Krasner were by then somewhat estranged (...), she was overcome with grief; there are those who believe she never fully recovered from the shock.

- ^ Farago, Jason (August 19, 2019). "Lee Krasner, Hiding in Plain Sight". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

Krasner received little attention from museums until her 60s, and she has rarely stepped out of the shadow of Jackson Pollock, her husband from 1945 until his early death in 1956.

- ^ "Lee Krasner Lauded in Memorial Service at the Met Museum". The New York Times. September 18, 1984. pp. Section B, Page 8. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Brenson, Michael. "Lee Krasner Pollock is Dead - Painter of New York School", The New York Times, Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Lee Krasner biography excerpt Retrieved March 1, 2016

- ^ "Lee Krasner Biography". Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ Anne M. Wagner. Three Artists (three Women): Modernism and the Art of Hesse, Krasner, and O'Keeffe. (Berkeley: University of California, 1996.) pg. 107

- ^ a b c Rose, Barbara. Lee Krasner: A Retrospective. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1983. pg. 13.

- ^ a b c d e Rose. 1983. pg. 14

- ^ Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, circa 1914-1984, bulk 1942-1984

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 15

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 16

- ^ a b Strassfield, Christina Mossaides. "Lee Krasner: The Nature of the Body-- Works from 1933 to 1984". East Hampton: Guild Hall Museum, 1995. pg. 6

- ^ a b Rose, 1983. pg. 18

- ^ Rose. 1983, pg. 22

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 26

- ^ Hobbs, Robert. Lee Krasner. New York: Abbeville Press, 1993. pg. 24

- ^ a b Rose, 1983. pg. 33

- ^ a b c Rose, Barbara. "Krasner|Pollock: A Working Relationship". New York: Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, 1981. pg. 5

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 34

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 45

- ^ a b Hobbs, 1993. pg. 32

- ^ Kleeblatt, Norman L., and Stephen Brown. From the Margins: Lee Krasner|Norman Lewis, 1945 - 1952. New York: Jewish Museum, 2014. pg. 15

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 40

- ^ Tucker, Marcia. "Lee Krasner: Large Paintings". New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1973.

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 50

- ^ a b c Hobbs. 1993. pg. 7

- ^ Hobbs. 1993. pg. 95

- ^ Hobbs, Robert. "Lee Krasner's Skepticism and Her Emergent Postmodernism", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 28, No.2, (Fall-Winter 2008): 3 – 10. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 3

- ^ Tucker. 1973. pg. 12

- ^ "Box 9, Folder 42 | A Finding Aid to the Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, circa 1914-1984, bulk 1942-1984 | Digitized Collection | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution".

- ^ Rose, 1981. pg. 6

- ^ Rose. 1981. pg. 4

- ^ a b c Hobbs. 1993. pg.40

- ^ Kleeblatt and Brown. 2014. pg. 68

- ^ a b c Rose. 1983. pg. 59

- ^ Cheim, John. "Lee Krasner: Paintings from 1965 to 1970". New York: Robert Miller, 1991. pg.4

- ^ Wagner, Anne M. "Lee Krasner as L.K.", Representations, No. 25 (Winter, 1989): 42-57. JSTOR. pg. 44

- ^ Kleeblatt and Brown. 2014. pg. 14

- ^ a b c Kleeblatt and Brown. 2014. pg. 19

- ^ Tucker. 1973. pg. 9

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 54

- ^ a b Kleeblatt and Brown. 2014. pg. 69

- ^ a b Levin, Gail. "Beyond the Pale: Lee Krasner and Jewish Culture", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 28, No.2 (Fall-Winter 2008): 28 – 44. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 44.

- ^ Kleeblatt and Brown. 2014. pg. 72

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 62

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 68

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 70

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 75

- ^ a b c Rose. 1983. pg. 82

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 83

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 93

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 79

- ^ Haxall, Daniel. "Collage and the Nature of Order: Lee Krasner's Pastoral Vision", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Fall-Winter 2008): 20-27. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 21

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 80

- ^ Landau, Ellen G. "Channeling Desire: Lee Krasner's Collages of the Early 1950s", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Autumn, 1997 – Winter, 1998): 27 – 30. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 27

- ^ Haxall, Fall-Winter 2008: 20-27. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 22

- ^ Haxall, Fall-Winter 2008: 20-27. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 20

- ^ a b Rose, 1983. pg. 100

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 97

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 104

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 108

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 117

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 126

- ^ Hobbs. 1993. pg. 73

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 122

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 125

- ^ Cheim, John. "Lee Krasner: Paintings from 1965 to 1970". New York: Robert Miller, 1991. pg. 21

- ^ a b c Rose. 1983. pg. 130

- ^ Strassfield, Christina Mossaides. "Lee Krasner: The Nature of the Body-- Works from 1933 to 1984". East Hampton: Guild Hall Museum, 1995. pg. 12

- ^ Hobbs. 1993. pg. 75

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 132

- ^ Rose. 1983. pg. 134

- ^ a b c Rose. 1983. pg. 10

- ^ Tucker. 1973. pg. 7

- ^ a b Cheim. 1991. pg. 9

- ^ Cheim. 1991. pg. 2

- ^ a b Rose. 1983. pg. 139

- ^ Hobbs, 1993. pg. 11

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 150

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 153

- ^ Hobbs, Robert. "Lee Krasner's Skepticism and Her Emergent Postmodernism", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 28, No.2, (Fall-Winter 2008): 3 – 10. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 8

- ^ Hobbs, Fall-Winter 2008: 3 – 10. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 7

- ^ Hobbs, 1993. pg. 88

- ^ Engelmann, Ines Janet. "Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner". Prestel, 2007. pg. 8

- ^ Raeburn, Michael (2015). Joseph Glasco: The Fifteenth American. London: Cacklegoose Press. p. 59. ISBN 9781611688542.

- ^ Rose, 1981. pg. 6.

- ^ Wagner, Winter 1989: 42 – 57. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 44

- ^ Wagner, Winter 1989: 42 – 57. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 45

- ^ Christiane., Weidemann (2008). 50 women artists you should know. Larass, Petra., Klier, Melanie, 1970-. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 9783791339566. OCLC 195744889.

- ^ Wagner, Winter 1989: 42 – 57. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 48

- ^ "Mary Beth Edelson". The Frost Art Museum Drawing Project. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Mary Beth Adelson". Clara - Database of Women Artists. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Women in the Arts. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Lord, M.G. (August 27, 1995). "ART; Lee Krasner, Before and After the Ball Was Over". The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Glueck, Grace (December 21, 1984). "Art: Lee Krasner Finds Her Place in Retrospective Ar Modern". The New York Times.

- ^ Kino, Carol (October 2, 2005). "A Visit With the Modern's First Grandmother". The New York Times.

- ^ "Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, circa 1905-1984". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ "The Pollock-Krasner Foundation website: Press Release page". Archived from the original on June 11, 2015.

- ^ "Most frequently requested artists list of the Artists Rights Society". Archived from the original on January 31, 2009.

- ^ Levin, Gail (2011). Lee Krasner : a biography.

- ^ Marter, Joan M. (2016). Women of abstract expressionism. Denver New Haven: Denver Art Museum Yale University Press. p. 183. ISBN 9780300208429.

- ^ Gabriel, Mary (2018). Ninth Street women : Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler : five painters and the movement that changed modern art (First ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0316226189.

- ^ "Action, Gesture, Paint". Whitechapel Gallery. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 48.

- ^ Rose, 1981. pg. 4.

- ^ Rose, 1981. pg. 8.

- ^ Rose, 1983. pg. 95.

- ^ Levin, Fall-Winter 2008: 28 – 44. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 28.

- ^ Levin. Fall-Winter 2008: 28 – 44. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 29.

- ^ a b Levin. Fall-Winter 2008: 28 – 44. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015. pg. 30.

- ^ "Self-Portrait".

- ^ "Gansevoort, Number 1".

- ^ "Night Creatures".

- ^ "Rising Green".

- ^ "Still Life".

- ^ "Seated Nude".

- ^ "untitled".

- ^ "Number 3 (Untitled)".

- ^ "Untitled".

- ^ "Gaea".

- ^ "Composition".

- ^ "Lee Krasner - Untitled, 1953". Abstract Expressionism - 14 July 2012 - 3 March 2013, International & Orde Poynton Galleries - National Library of Australia. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "Milkweed". www.albrightknox.org. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Lee Krasner, Polar Stampede, 1960 · SFMOMA". www.sfmoma.org. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Gold Stone, from the Primary Series - Lee Krasner". Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. September 20, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Comet".

- ^ "Krasner, Lee - American, 1908-1984". National Gallery of Art. 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "Krasner, Lee - American, 1908-1984". University of Wisconsin-Stout. 2023. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ Souren Melikian (November 13, 2003), Auctions: Big art, monumental prices International Herald Tribune.

- ^ Margaret Carrigan (May 17, 2019), San Francisco museum's Rothko sells for $50m as Sotheby’s closes bumper week of New York auctions The Art Newspaper.

Sources & further reading

[edit]- Cheim, John. Lee Krasner: Paintings from 1965 to 1970. New York: Robert Miller, 1991.

- Gabriel, Mary. Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: five painters and the movement that changed modern art. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2018

- Haxall, Daniel. "Collage and the Nature of Order: Lee Krasner's Pastoral Vision", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Fall-Winter 2008): 20-27. JSTOR. Web.

- Herskovic, Marika. American Abstract and Figurative Expressionism Style Is Timely Art Is Timeless (New York School Press, 2009.) ISBN 978-0-9677994-2-1. p. 144-147

- Herskovic, Marika. American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s An Illustrated Survey, (New York School Press, 2003.) ISBN 0-9677994-1-4. p. 194-197

- Herskovic, Marika. New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists, (New York School Press, 2000.) ISBN 0-9677994-0-6. p. 16; p. 37; p. 210-213

- Hobbs, Robert. Lee Krasner. New York: Abbeville Press, 1993.

- Hobbs, Robert. "Lee Krasner's Skepticism and Her Emergent Postmodernism", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 28, No.2, (Fall-Winter 2008): 3 – 10. JSTOR. Web.

- Howard, Richard and John Cheim. Umber Paintings, 1959–1962. New York: Robert Miller Gallery, 1993. ISBN 0-944680-43-7

- Kleeblatt, Norman L., and Stephen Brown. From the Margins: Lee Krasner|Norman Lewis, 1945 - 1952 . New York: Jewish Museum, 2014.

- Landau, Ellen G. "Channeling Desire: Lee Krasner's Collages of the Early 1950s", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Autumn, 1997 – Winter, 1998): 27 – 30. JSTOR. Web.

- Levin, Gail. "Beyond the Pale: Lee Krasner and Jewish Culture", Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 28, No.2 (Fall-Winter 2008): 28 – 44. JSTOR. Web.

- Levin, Gail. Lee Krasner: A Biography. (New York: HarperCollins 2012.) ISBN 0-0618-4527-2

- Pollock, Griselda, Killing Men and Dying Women. In: Orton, Fred and Pollock, Griselda (eds), Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed. London: Redwood Books, 1996. ISBN 0-7190-4398-0

- Robertson, Bryan; Robert Miller Gallery New York, Lee Krasner Collages (New York : Robert Miller Gallery, 1986)

- Robertson, Bryan. Lee Krasner, Collages. New York: Robert Miller Gallery, 1986.

- Rose, Barbara. Krasner|Pollock: A Working Relationship. New York: Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, 1981.

- Rose, Barbara. Lee Krasner: a retrospective Lee Krasner: A Retrospective] (Houston : Museum of Fine Arts; New York : Museum of Modern Art, ©1983.) ISBN 0-87070-415-X

- Strassfield, Christina Mossaides. Lee Krasner: The Nature of the Body—Works from 1933 to 1984. East Hampton: Guild Hall Museum, 1995.

- Tucker, Marcia. Lee Krasner: Large Paintings. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1973.

- Wagner, Anne. "Lee Krasner as L.K.", Representations, No. 25 (Winter 1989): 42 – 57. JSTOR. Web. March 17, 2015.

External links

[edit]- “Lee Krasner: Not Just Another Abstract-Expressionist” by Christopher P. Jones, Medium.

- “‘A Jewish woman, a widow, a damn good painter and a little too independent’ — reclaiming Lee Krasner’s legacy” by Laurie Gwen Shapiro. Forward, February 27, 2024.

- Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, circa 1905-1984, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- The Pollock-Krasner Foundation

- Oral history interview with Lee Krasner, 1964 Nov. 2-1968 Apr. 11

- Oral history interview with Lee Krasner, 1972, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- Entry for Lee Krasner on the Union List of Artist Names

- 1978 Lee Krasner video interview by Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel

- Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction | HOW TO SEE with MoMA curator Starr Figura

- 1908 births

- 1984 deaths

- Painters from Brooklyn

- Jewish American artists

- American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- 20th-century American painters

- Abstract expressionist artists

- American abstract painters

- American contemporary painters

- American printmakers

- American women printmakers

- American collage artists

- American women collage artists

- Jewish American painters

- Art Students League of New York alumni

- Cooper Union alumni

- People from East Hampton (town), New York

- Federal Art Project artists

- 20th-century American women painters

- Jackson Pollock

- Burials at Green River Cemetery