Jonathan Agnew

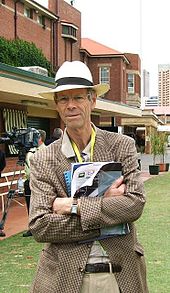

Agnew at the Adelaide Oval in 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Jonathan Philip Agnew | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 4 April 1960 Macclesfield, Cheshire, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Aggers, Spiro | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm fast | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 508) | 9 August 1984 v West Indies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 6 August 1985 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ODI debut (cap 77) | 23 January 1985 v India | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last ODI | 17 February 1985 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1979–1992 | Leicestershire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Cricinfo, 5 August 2008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jonathan Philip Agnew, MBE, DL (born 4 April 1960) is an English cricket broadcaster and a former cricketer. He was born in Macclesfield, Cheshire, and educated at Uppingham School. He is nicknamed "Aggers" and, less commonly, "Spiro" – the latter, according to Debrett's Cricketers' Who's Who, after former US Vice-President Spiro Agnew.[1]

Agnew had a first-class career as a fast bowler for Leicestershire from 1979 to 1990, returning briefly in 1992. In first-class cricket he took 666 wickets at an average of 29.25. Agnew won three Test caps for England, as well as playing three One Day Internationals in the mid-1980s, although his entire international career lasted just under a year. In county cricket, Agnew's most successful seasons came toward the end of his career when he had learned to swing the ball. He was second- and third-leading wicket-taker in 1987 and 1988 respectively, including the achievement of 100 wickets in a season in 1987. He was named as one of the five Cricketers of the Year by Wisden Cricketers' Almanack in 1988.

While still a player, Agnew began a career in cricket journalism and commentary. Since his retirement as a player, he has become a leading voice of cricket on radio, as the BBC Radio cricket correspondent and as a commentator on Test Match Special. He has also contributed as a member of Australian broadcaster Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Grandstand team.

Agnew's on-air "leg over" comment on Test Match Special, made to fellow commentator Brian Johnston in 1991, provoked giggling fits during a live broadcast and widespread reaction. The incident has been voted "the greatest sporting commentary ever" in a BBC poll.[2]

Agnew has been called "a master broadcaster ... the pick of the sports correspondents at the BBC."[3]

Playing career

[edit]Background and early years

[edit]Agnew was born on 4 April 1960 at West Park Hospital in Macclesfield, Cheshire, to Margaret (née McConnell) and Philip Agnew.[4][5] His parents' forthcoming marriage was announced in The Times in 1957: Philip Agnew was described as "the only son of Mr and Mrs Norris M. Agnew of Dukenfield Hall, Mobberley, Cheshire" and Margaret as "youngest daughter of Mr and Mrs A.F.V. McConnell of Hampton Hall, Worthen, Shropshire".[6] The Agnews had a second son in June 1962 and were recorded as living at "Bainton near Stamford, Lincs"; in April 1966, a daughter, Felicity, was born and was announced as "a sister for Jonathan and Christopher".[7][8] Agnew's paternal grandmother, Lady Mona Agnew, died aged 110 years and 170 days in 2010 and was on the list of the 100 longest-lived British people ever.[9]

Jonathan Agnew recalls growing up on the family farm and first becoming aware of cricket aged "eight or nine"; his father would carry a radio around and listen to Test Match Special:

"The programme sparked an interest in me, in the same way it has in so many tens of thousands of children down the years, igniting a passion that lasts a lifetime."[10]

Driven by early enjoyment of the media coverage of cricket, Agnew developed a love for playing the game. At the end of days spent watching cricket on television in a blacked-out room with the commentary provided by the radio, Agnew would go into the garden and practise his bowling for hours, trying to imitate the players he had seen.[11] Agnew's father, an amateur cricketer, taught him the rudiments of the sport, including an offspin action, as he wanted his son to develop into a bowler like him.[10] Another family connection to cricket was his first cousin, Mary Duggan, who was a women's Test player for England from 1948 to 1963.[12]

From the age of eight, Agnew boarded at Taverham Hall School near Norwich.[13] His first cricket coach was Eileen Ryder and, according to Agnew, after "a couple of years"[14] a professional arrived at the school: Ken Taylor, a former batsman for Yorkshire who had played three Tests for England in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[14]

Agnew attended Uppingham School for his secondary education,[5] and left in 1978 with nine O-levels and two A-levels in German and English.[12] From the age of 16 he developed his skills as a right-arm fast bowler out of school hours at Alf Gover's cricket school whilst at Surrey County Cricket Club.[15] That summer, he saw fast bowler Michael Holding take 14 wickets in the 1976 Oval Test match, a performance of pace bowling referred to as "devastating" by cricket writer Norman Preston,[16] which made a lasting impression on Agnew.[17] More than 30 years later he wrote of his bowling during his schooldays:

"For an eighteen-year-old bowler I was unusually fast, and enjoyed terrorising our opponents, be they schoolboys (8 wickets for 2 runs and 7 for 11 stick in the memory) or, better still, the teachers in the annual staff match. This, I gather, used to be a friendly affair until I turned up, and I relished the chance to settle a few scores on behalf of my friends – for whom I was the equivalent of a hired assassin – as well as for myself."[18]

Having played for Surrey under-19s the previous year,[19] he began playing for Surrey's second XI in 1977,[20] but Surrey made no move to sign him as a player. At a home match against Hampshire, the teenage Agnew was the only player to stand up to then Surrey coach and former England player Fred Titmus after the latter racially abused the Guyanese-born Surrey player Lonsdale Skinner, an incident of which Agnew later said: "The consequences hadn’t really dawned on me. But clearly it was a career-ender".[19][21] Leicestershire County Cricket Club did, however, take note of Agnew's impressive performances in local club cricket and for Uppingham School, for whom he took 37 wickets at a bowling average of 8 in 1977,[5] and signed him while he was still a schoolboy in time for the 1978 season.[18]

County cricket

[edit]On his first-class debut against Lancashire in August 1978,[22] the 18-year-old Agnew bowled to England international David Lloyd, an opening batsman with nine Test caps.[23] Reported in Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, Lloyd "was halfway through a forward defensive push when his off stump was despatched halfway towards the Leicestershire wicket-keeper."[15] Agnew took one wicket in each innings of the match, and did not bat; Leicestershire won by an innings.[24]

Agnew won a Whitbread Brewery award at the end of his debut season, an achievement he ascribes to the influence of his county captain, Ray Illingworth:[25] he had taken only six first-class wickets at an average of 35.[26] Illingworth was quoted in The Times as saying that Agnew was "the second fastest bowler" in England in 1978, behind only Bob Willis.[27] The award afforded him the opportunity to spend a winter in Australia developing his skills, alongside fellow winners Mike Gatting, Wayne Larkins and Chris Tavaré,[28] and to be coached by former England fast bowler, Frank Tyson.[27] All four went on to play Test cricket.[note 1] On that Australia tour, Agnew played his only youth Test, but made headlines when invited to bowl at the touring England team in the nets:

"He struck the captain, Mike Brearley, a nasty blow in the face. It was, Agnew recalls, merely a gentle delivery off two paces that flew off a wet patch; but it did not deter the headline writers. Such early publicity did him no favours, but when a bowler arrives who is young, fast and English, a quiet settling-in period to one of the more difficult apprenticeships in sport is often denied him." – Wisden[15]

Agnew's 1979 season was disrupted by injury. The Editor's Notes of the 1980 Wisden Cricketers' Almanack reported, under the heading "England's Promising Youngsters", that Agnew had strengthened himself over the winter by felling trees.[30] Agnew's own account is that 1979–80 was "the worst winter of his life", although his recollection is that he spent it working as a lorry driver.[31] He did, however, make his List A limited overs debut in 1979, playing just once, against the Sri Lanka touring team – his competitive List A debut followed in 1980, in the Benson & Hedges Cup against Scotland:[32] he bowled just three overs (for five runs) and did not bat.[33]

Test cricket

[edit]

Agnew's career did not initially live up to his early promise. In his first six seasons as a first-class cricketer, his largest haul of wickets was 31 in 1980.[34] The 1984 season was his breakthrough year: he played 23 first-class matches,[35] taking 84 wickets at an average of 28.72.[34] Playing in the warm-up game against Cambridge University, he achieved figures of 8–47 (taking 8 wickets while conceding 47 runs) from 20.4 overs and was included in the first team for the County Championship matches that followed.[36]

He carried that success forward into the County Championship, picking up wickets for Leicestershire including a ten wicket match haul against Surrey in June,[37] and five wickets in an innings against Kent in the days leading up to the fifth Test against West Indies.[38] The England selectors took note and, with the West Indies leading the series 4–0, Agnew and Richard Ellison were given debuts,[39] in an ultimately unsuccessful effort to avoid the "blackwash".[40]

Wisden describes how in the first innings, Agnew's accuracy was affected by debutant nerves,[41] but an improved display in the second innings resulted in figures of 2–51.[39] Agnew describes how Ian Botham helped him secure both wickets, catching Gordon Greenidge in the slips, and passing on some advice on how to dismiss Viv Richards, Botham's great friend: "Botham said: 'Right. Don't pitch a single ball up at him. Have two men back for the hook, and bowl short every ball.' This I did for three overs or so, by which time Viv was looking a little exasperated, but was definitely on the back foot. Finally I pitched one up, the great man missed it and umpire David Constant ruled that Richards was LBW for 15."[42] Wisden called the pair of batsmen Agnew's "first illustrious victims in Test cricket".[41]

England's next match was a one-off home Test against Sri Lanka and Agnew retained his place in the England team. At the time, Sri Lanka were regarded as the minnows of world cricket:[43] this was only their 12th Test match and their first at Lord's,[44] but they dominated the match, taking a 121-run lead on first innings and declaring twice.[45] It was a disappointment for England and, in a batsman-friendly match in which the Sri Lankans racked up 785 runs for just 14 wickets, Agnew suffered. Wisden described England's pacemen as ineffective;[44] Agnew's match figures were 2–177 off 43 overs.[45] Poor performance and a muscle injury limited him to bowling a single over on the last day; later, Agnew reflected on other negative aspects of this match: "I felt a complete outsider, not part of the set-up. I think the feeling in the dressing room was that the game had been a bit of a cock-up."[46]

England toured India and Sri Lanka that winter. Agnew replaced the injured Paul Allott after the second Test. However, he failed to be selected for a Test match, with England's decision to field two spinners (Pat Pocock and Phil Edmonds) in each Test playing a part in limiting Agnew's opportunities.[47] Agnew played just one first-class match on the tour,[48] versus South Zone in Secunderabad, achieving match figures of seven wickets at an average of 29,[49] but he did play in three One Day Internationals (ODIs), two in India and one in Australia.[50] His debut ODI was promising, as he took 3–38 in a losing cause.[51] However, in his remaining two ODIs, he proved very expensive, taking no further wickets and conceding more than seven runs an over in each.[52][53]

Agnew began the 1985 season vying with the established England fast bowlers to get back into the Test side. Over the winter, the side had been settled, with Norman Cowans and Chris Cowdrey playing all five Tests. Neil Foster and Richard Ellison shared the third spot alongside the spinners, playing two and three Tests respectively.[47] Cowdrey and Ellison had struggled with the ball, both averaging more than 70.[54] However, the side was extensively remodelled for the first Test of that summer's Ashes series.[55] Of the bowlers who had played the last Test in India, only Cowans had survived the cull and it set the tone for the series. England won the first Test, yet dropped Cowans and Peter Willey, replacing them with Phil Edmonds and Foster. After losing the second Test, and struggling with the ball in the third Test, when Australia made 539 all out in their only innings,[56] England decided to make further changes.

Agnew had performed consistently in county cricket through June and July,[57] culminating in what was to be, statistically, his finest moment as a bowler. Playing against Kent, he took 9–70 in the first innings.[58] His timing was perfect and he was called up for the Fourth Test at Old Trafford to partner Ian Botham and Paul Allott in an all-Cheshire born seam attack. The match finished as a draw, and Agnew failed to take a wicket. He was relegated from an opening bowler in the first innings, to fifth bowler in the second, in which he only bowled nine overs.[59] He was subsequently dropped again from the side, only for Richard Ellison to cement his place with match-winning performances that helped claim the Ashes for England.[60]

Later playing career and retirement

[edit]In the 1987 season, Agnew achieved the feat of 100 first-class wickets in an English cricket season when he took 101 wickets for his county.[61] He was the first Leicestershire player to achieve this milestone since Jack Birkenshaw in 1968,[15] which was the season before the county programme was greatly reduced, making the feat much less common.[62][note 2] By this stage, he was working on local radio during the winters and he found the reassurance of the additional income and career path a major factor in his improved form.[61] Wisden preferred to attribute his success to "bowling off a shorter run and ... a wicked slower ball added to his armoury".[15] The achievement led to him being selected as one of the five Wisden Cricketers of the Year.[15]

Agnew's form remained good: he followed his 1987 feat of taking the second-most wickets in the County Championship[64] by taking the third-most in 1988.[65] In 1989, with two years of good form behind him and England losing 4–0 in the 1989 Ashes series,[note 3] Agnew "came frustratingly close to the recall to the England team that I had set my heart on."[61]

County captain and friend of Agnew, David Gower was England captain, and a number of fast bowlers from around the country called the telephone in the Leicestershire dressing room, to tell Gower that they were injured and unavailable for the Sixth Test.[61] According to Agnew's account, Gower was at a loss as to whom to call into the squad.[61]

Agnew recalls that county colleague Peter Willey made a suggestion:

"'What about Agnew?' suggested Peter Willey ... 'He's bowling pretty well at the moment.' David's face lit up. 'Of course!' he said. 'Jonathan, you're in. Go home, get your England stuff ready, and I'll call first thing tomorrow ...' Even though I was approximately the seventeenth choice, this was still fantastic news ... After three disappointing Test appearances, this was my second chance, and the opportunity to set the record straight ... [The following day] the telephone finally rang. 'Got some bad news, I'm afraid,' David began. 'I couldn't persuade Ted Dexter or Mickey Stewart, so you're not in any more. They've gone for Alan Igglesden. Know anything about him?' With that, David must have known his influence as England captain was over – and indeed Graham Gooch succeeded him after that Test. I felt utterly devastated, and knew I would never play for England again, which had been my main motivating force. So when the Today newspaper offered me the post of cricket correspondent the following summer, it was an easy decision to make. I might have been only thirty, which was no age to retire from professional cricket, and I could easily have played for another five years. But it was definitely time to move on."[66]

Agnew formally retired from playing professional cricket at the end of the following season: Leicestershire's last match of the 1990 Championship season was his last first-class game.[67] Aged 30,[68] Agnew took 1–42 in Derbyshire's only innings and scored 6 in his only turn to bat.[22][67] In 1992, two years after retirement, Leicestershire experienced an injury crisis before their NatWest Trophy semi-final against Essex. Agnew answered a request to assist and played, finishing the match with figures of 12–2–31–1 (bowling twelve overs, including two maiden overs, and taking one wicket for 31 runs). Leicestershire won the match and progressed to the final, but Agnew chose not to play.[69]

Playing style and career summary

[edit]Agnew's best first-class bowling figures were 9 for 70 and he took six ten-wicket hauls in 218 matches. In the 1988 Cricketer of the Year editorial on Agnew,[note 4] Wisden noted that "his pace comes from a whippy wrist action and co-ordination ... In the field, Agnew has at times appeared to be moving with his bootlaces tied together, but his long run-up was one of the more graceful in the game. However, it was the shortening of that run-up, and a cutting-down of pace, which led to ... achievements [late in his career]"[15]

As a batsman, Agnew had some highs, but it was his weaker suit. His highest first-class batting score was 90, starting initially as nightwatchman in 1987 against Yorkshire, at North Marine Road Ground, Scarborough. Wisden commented, "Agnew hit a spectacular, career-best 90 from 68 balls, including six sixes and eight fours, and then took the first five Yorkshire wickets to fall".[70] Wisden commented that Agnew was no all-rounder, but he could "certainly bat ... on his day he can destroy anything pitched up around off stump."[15] The same piece noted his usual playing style, "playing hard but always with a sense of fun".[15]

Agnew reflects on his playing career as having had two periods:

"My career could be divided up into two sections: the first being when I was an out-and-out fast bowler and played for England when I probably should not have done; and the second being when I slowed down a bit, learned how to swing the ball and did not play for England when I probably should have done.[71]

His final Test was only twelve months after his England debut, and his first and last ODIs were played less than a month apart. Cricket commentator Colin Bateman opined, "his fleeting taste of Test cricket should have been added to in 1987 and 1988 when he was the most consistent fast bowler in the country, taking 194 wickets, but in 1989, when England were desperate for pace bowlers, his omission amounted to wanton neglect by a regime which questioned his desire".[72] In 1988, when Agnew was selected as a Cricketer of the Year, Wisden recorded this verdict on the contrariness of Agnew's Test career: "Asked about Agnew's omission, the chairman of selectors, P. B. H. May, expressed concern about his fitness – rather a baffling statement to make about someone who bowled more overs than any other fast bowler in the Championship."[15]

Media and broadcasting career

[edit]

Agnew began gaining experience as a journalist in 1987, while still playing cricket, when at the invitation of John Rawling he took off-season employment with BBC Radio Leicester as a sports producer.[31] It was during this period that he "fell in love with radio",[31] and following his retirement, he had a short stint as chief cricket writer of Today newspaper.[73] While covering the 1990–91 Ashes series for Today, he was approached by Peter Baxter about joining Test Match Special.[74] Unhappy at certain editorial decisions that had been taken during his time with the newspaper, Agnew agreed to attend an interview after the tour.[74]

Agnew joined Test Match Special in 1991,[75] in time for the first Test match of the summer.[76] He was initially a junior member of the Test Match Special team, learning at close quarters from figures such as Brian Johnston, Henry Blofeld and Bill Frindall. The same year, he was also appointed the BBC's cricket correspondent,[75] taking over from Test Match Special colleague, Christopher Martin-Jenkins.[77] In 2007, when asked which sports journalist he most respected, Martin-Jenkins named Agnew, because he "combines astute journalism with apparently effortless communication skills."[78] He has also commentated for the Australian ABC Radio network during Ashes series in Australia.[79]

When Channel 4 won the broadcasting rights to television coverage of England's home Test matches in 1998, Agnew was approached by the broadcaster and offered a job on the commentary team.[80] Agnew declined the opportunity, opting to remain BBC cricket correspondent, in part because he was a "radio man" and in part out of loyalty.[80] The following year, England hosted the 1999 Cricket World Cup. The BBC had the UK television rights, but with so many specialist TV cricket presenters now at Channel 4 and therefore unavailable to the BBC, Agnew was asked to present the coverage.[81] His recollections of the experience are that it was something of a trial, helped only by the experienced Richie Benaud alongside him:

I really had no option but to agree to do it, despite my reservations about working in television. Coming so quickly after my decision to stay on the radio, this was quite an irony. I was given one day of training ... [Transmission ended with the presenter being given a countdown] from one minute to zero, at which point you have to say goodbye. I did not find that easy at all ... I made a real hash of it after one of the early games ... [Richie] ... very kindly, suggested a plan ... as soon as the count started in our earpieces I would ask him a question, and he would talk until the count reached eight seconds to go. I would then thank him, turn to the camera and tell the audience briefly about the next game to be televised. Miraculously, for the rest of the tournament I always heard 'zero' in my ear at the moment I said goodbye ... the whole experience served to confirm my belief that my decision to stick with Test Match Special was the right one.[82]

In addition to his writing and broadcasting work, Agnew's commentary has been recorded for several computer games, including the International Cricket Captain and Brian Lara Cricket series.[83][84] He is a shareholder in TestMatchExtra.com Ltd, a company which runs the website of the same address and acquired The Wisden Cricketer magazine from BSkyB in December 2010.[85][86]

From 2001 to 2005, Agnew provided the voice of Flynn, the oval-shaped screen, on children's gameshow 50/50.

Agnew has won many awards for his broadcasting, including two Sony Awards for Best Reporter (1992 and 1994), and Best Radio Broadcaster of the Year (2010), an award from the Association of Sports Journalists.[77] Agnew was made an Honorary Doctor of Arts by De Montfort University, Leicester in November 2008,[87] and an Honorary Doctor of Letters by Loughborough University in July 2011.[88]

His peers in sports journalism have frequently commented on Agnew's skills as a broadcaster and writer. Michael Henderson, in the aftermath of the Stanford cricket controversy, wrote of Agnew as a "master broadcaster ... the pick of the sports correspondents at the BBC ... Agnew's is a sane, reasonable voice in a game that is going potty. Fair-minded, even-tempered, he has become one of the finest specialists the BBC has ever had. In his understated way he speaks for the game: not the people who play it."[3]

In 2016 Agnew was a member of the BBC commentary team at the 2016 Summer Olympics, covering equestrian events.[89] He earns £185,000 – £189,999 as BBC cricket correspondent.[90]

Agnew was appointed as a Deputy Lieutenant of Leicestershire in October 2015,[91] and as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 2017 New Year Honours for services to broadcasting.[92]

On 26 October 2024, following the conclusion of England's unsuccesful three-test match tour of Pakistan, Agnew confirmed in an article on the BBC Sport website that that this England cricket tour would be his last as the BBC's chief cricket correspondent, a role he had held for 33 years. Agnew did however clarify he would continue to serve as presenter and commentator on the Test Match Special radio programme.[93]

Notable broadcasting incidents

[edit]

In 2001, Agnew was part of the BBC team that was sent to Sri Lanka to cover England's Test match series.[94] As a result of confusion and a row over broadcasting rights, the BBC team found itself barred from the Galle International Stadium, where the first Test was to take place.[94] Agnew and Pat Murphy refused to be defeated and "decamped to the fort ramparts overlooking the ground and broadcast their programme from there. With both team and equipment protected from the sun by an umbrella held by Mr Agnew's driver, Simmons, it made a colourful scene."[94] The England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) chief executive, Tim Lamb became involved in discussions and the Test Match Special team were allowed to return to the ground.[94]

The Daily Telegraph called Agnew and Murphy's effort, "new heights of ingenuity".[95] Agnew's reaction to the event was, "It's a sad day for everyone involved in English cricket. Is it really that cricket is getting so greedy that everyone who wants to come and report on the game for the good of the game is going to have to be charged for it?"[95] However, he remained upbeat about the situation: "Actually I get rather more of a panoramic view of it from up here than I did yesterday in my commentary box. There's a little road that runs round the back of the ground. All manner of people are trundling up and down – buses, bikes and little three wheeled tuk-tuks – it's rather fun."[95]

In 2004, the Zimbabwe government banned media from following the England cricket team tour of the country.[96] Agnew's reaction was combative, appearing on BBC Breakfast and giving his opinion that the ban presented the ECB with a chance to withdraw from the controversial tour and that they should take the opportunity.[96]

In the summer of 2008, then England captain Michael Vaughan reacted testily on-air to questions by Agnew about his batting form. When Vaughan resigned shortly thereafter, Mike Atherton, writing in The Times, commented that it had been an out-of-character outburst that was a portent of the resignation.[97] When Atherton had himself been England captain, Agnew had led the calls for Atherton to resign over a controversy known as the "dirt in the pocket" affair.[96] Fellow BBC commentator Jack Bannister felt that Agnew's comments were inappropriate, but only to the extent that he had referred to his friendship with Atherton: Bannister advised Agnew that he should continue to be honest and forthright as a reporter.[98]

Agnew was involved in a minor controversy regarding an appearance by Lily Allen on Test Match Special in 2009.[99] The Daily Telegraph reported that "the cricket-loving Allen struck up an instant rapport with Agnew, and the BBC received largely positive feedback for the 30-minute interview", but Will Buckley, writing for The Observer, described Agnew's "amorous ambitions" as "positioned ... firmly on the pervy side of things".[100] Agnew was furious, noting he "gave ... Will Buckley 24 hrs to apologise for calling me a pervert, and he has declined ... As you can imagine, I have taken being called a pervert quite badly."[99] Allen herself supported Agnew: "[I] really think this Will Buckley guy should apologise to ... [Agnew], he was nothing but kind and gentlemanly to me during our interview. I don't know 1 person that agrees with The Observer on this one."[99] Buckley eventually apologised.

"Leg over" incident

[edit]Agnew has been known to laugh at or include occasional sexual innuendo while on air.[101][102] One example took place in August 1991, when Agnew was commentating with Brian Johnston. In a review of the day, Johnston was describing how Ian Botham, while batting, had overbalanced and tried, but failed, to step over his stumps. Botham was consequently given out hit wicket. Agnew's comment on this action was: "He just didn't quite get his leg over."[103] Botham had attracted a number of headlines during his career for his sexual exploits and in British English, "getting one's leg over" is a euphemism for having sexual intercourse.[104]

The comment led to Johnston becoming incapacitated by laughter.[105] He initially tried to continue his summary, before becoming unable to speak for laughing, at one point saying "Aggers, for goodness' sake, stop it" as he struggled to regain his composure.

The incident was heard by thousands of commuters driving home from work, many of whom were forced to stop driving because they were laughing so much:[103][105] a two-mile traffic jam at the entrance to the Dartford Tunnel was reportedly caused by drivers unable to pay the toll due to laughter.[103] Fourteen years later, in 2005, Agnew's line, "Just didn't quite get his leg over" was voted "the greatest sporting commentary of all time" by listeners to BBC Radio 5 Live.[2] The other eight finalists included Kenneth Wolstenholme's "They think it's all over – it is now!" and Ian Robertson's "This is the one. He drops for World Cup glory ... It's up! It's over! He's done it! Jonny Wilkinson is England's hero yet again".[2] Agnew and Johnston secured 78% of the votes.[106]

Private life

[edit]Agnew's first marriage was to Beverley in 1983;[12] it ended in divorce in 1992, a year after he became BBC cricket correspondent.[107] He has written about the role that cricket played in the collapse of the relationship, comparing his circumstances with those of then England batsman Graham Thorpe.[107] He also found that his job interfered with his relationship with his children:

I had two young children, aged seven and five ... it was quickly evident that for me to have custody of my daughters – or even to form a relationship with them – was made impossible by my job. What chance do you have when, be it playing Test cricket or commentating on it, you are away for months at a time each and every winter? ... There was one occasion when I did not recognise my eldest, Jennifer, when I returned from one tour ... my children continue to ask me why I did not resign and take a job that would have kept me in the country and allowed me to see them more often. I find that one especially hard to answer."[107]

Agnew has subsequently remarried: he met Emma Agnew, current editor of BBC East Midlands Today,[108] when they worked together on BBC Radio Leicestershire.[109]

In 2013 Agnew told BBC Desert Island Discs he struggled to maintain contact with his daughters after his divorce from their mother saying he wanted to "stand up" for absent fathers in broken families. Agnew's first wife and two daughters responded to this claiming Agnew had made little effort to stay in contact with his daughters.[110][111]

Agnew suffers from Dupuytren's contracture, a medical condition that affects the connective tissue in his hands. He has had numerous operations to address the progressive condition, which causes the hands to contract into a claw-like position.[112]

Personality

[edit]During Agnew's playing career, a dispute with team-mate Phillip DeFreitas attracted media attention: when DeFreitas poured salt over Agnew's lunch, Agnew responded by throwing DeFreitas' cricket bag and kit from the dressing room balcony.[113] Former England cricketer Derek Pringle has written about Agnew's sense of humour, describing him as "hysterical".[114] The pair toured Sri Lanka together on England B's 1986 tour.[115] Pringle recalls that one hot day when England were in the field, Agnew came in for lunch: "It's ****ing red hot on the field, and when you come off it's ****ing red hot in the dressing-room," Agnew screamed. "Then, what do you get for lunch, ****ing red hot curry?"[114]

Assisted suicide allegation

[edit]It was reported in various newspapers in 2013 that Agnew had offered to accompany Brian Dodds, his second wife's ex-husband, to the Dignitas assisted suicide clinic in Zürich after Dodds was diagnosed with motor neurone disease. Dodds died in England from the disease in 2005.[116]

BBC reprimand

[edit]In 2019, journalist Jonathan Liew wrote an article in which he expressed concern about some of the language used in the media to describe Jofra Archer’s selection for England. Liew wrote “Who doesn’t love morale and camaraderie, after all? – Until you begin to question why Archer is deemed such a grave threat to it.” Agnew called Liew a "“sad racist troll after clickbait” on Twitter,[117] adding “Fucking disgrace. You have massive chips on your shoulders… you are a racist.” Agnew then went on to describe Liew as "strange" and "a cunt" followed by questioning “who the fuck are you”. Agnew was reprimanded by the BBC;[118] he also deleted his Twitter account.[117] Writing about the incident, journalist Barney Ronay stated, "Agnew has done something similar but far less serious and bullying with me. Those who know him say Agnew is a very nice man, that he can just be thin-skinned. This is probably right."[119]

In October 2022 a conversation between Agnew and Liew was published by The Observer where the two men discussed the incident. Agnew told Liew that "to associate a white middle-aged person with racism is a massive hit. And that’s what really upset me, because I know I’m not." Agnew claimed that when he was a teenage player in the 1970s he objected when Fred Titmus used racist language against Lonsdale Skinner.[19]

Bibliography

[edit]Agnew has written four books:

- 8 Days a Week: Diary of a Professional Cricketer. Ringpress. 1988. ISBN 0-948955-30-9.

- Over to You, Aggers. Gollancz. 1997. ISBN 0-575-06454-4.

- Thanks, Johnners: An Affectionate Tribute to a Broadcasting Legend. HarperCollins. 2010. ISBN 978-0-00-734309-6.

- Aggers' Ashes. HarperCollins. 2011. ISBN 978-0-00-734312-6.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sproat, Iain, ed. (1980). Debrett's Cricketers' Who's Who (1980 ed.). Debrett's Peerage Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 0-905649-26-5.

- ^ a b c Culf, Andrew (20 August 2005). "The incident which led to the greatest sporting commentary of all time (according to 5 Live listeners): 'He just couldn't get his leg over'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ a b Henderson, Michael (24 February 2009). "Aggers puts Radio Halfwit in its place". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "Births". The Times. No. 54739. London. 6 April 1960. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Jonathan Agnew". ESPNcricinfo. ESPN. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Forthcoming marriages". The Times. No. 53806. London. 3 April 1957. p. 12.

- ^ "Births". The Times. No. 55423. London. 21 June 1962. p. 1.

- ^ "Births". The Times. No. 56607. London. 16 April 1966. p. 1.

- ^ "Death Announcements". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ a b Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 7

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 8

- ^ a b c Sproat, Iain, ed. (4 April 1991). The Cricketers' Who's Who (1991 ed.). Collins Willow. p. 11. ISBN 0-00-218396-X.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 10

- ^ a b Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Cricketer of the Year, 1988 : Jonathan Agnew". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. ESPN. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Preston, Norman. "England v West Indies". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ Buckland, William (14 April 2008). Pommies: England Cricket Through an Australian Lens. Matador. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-906510-32-9.

jonathan agnew.

- ^ a b Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 35

- ^ a b c Liew, Jonathan (23 October 2022). "'So yeah, I wrote this piece …' Jonathan Liew meets Jonathan Agnew". theguardian.com. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ "Second Eleven Championship Matches played by Jonathan Agnew". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Ronay, Barney (26 July 2020). "Lonsdale Skinner:'Most of the racism came from the committee room'". theguardian.com. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ a b "First Class matches played by Jonathan Agnew". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "David Lloyd". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ "Leicestershire v Lancashire in 1979". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners, p. 38

- ^ "First-class Bowling in each season by Jon Agnew". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Young fast bowler to be coached by Tyson". The Times. No. 60416. London. 26 September 1978. p. 13.

- ^ Preston, Norman. "Curbing the bouncer, and more 1979 – Notes by the Editor". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. ESPN. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Records / England / Test matches / Batting averages". ESPNcricinfo. ESPN. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Preston, Norman. "Recodification of the laws and more, 1980 – Notes by the Editor". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. ESPN. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ a b c "Jonathan Agnew: My Life in Media". The Independent. London. 25 July 2005. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "List A Matches played by Jon Agnew". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Scotland v Leicestershire – Benson and Hedges Cup 1980 (Group A)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ a b "First Class bowling each season by Jonathan Agnew". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "First Class batting each season by Jonathan Agnew". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Cambridge University v Leicestershire". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Surrey v Leicestershire in 1984". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ "Kent v Leicestershire in 1984". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ a b "The Wisden Trophy – 5th Test". ESPNcricinfo. ESPN. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "31 years of hurt". BBC Sport. 4 September 2000. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ a b "England v West Indies, 1984". ESPNcricinfo. ESPN. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 41

- ^ Thuraisingam, Ragavan (3 January 2001). "CricInfo talks to Ravi Ratnayeke". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ a b "England v Sri Lanka 1984". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. ESPN. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ a b "England v Sri Lanka in 1984". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Williamson, Martin (4 June 2011). "Sri Lanka's impressive Lord's debut". ESPNcricinfo. ESPN. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Test batting and fielding for England – England in India 1984/85". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "First-class batting and fielding for England – England in India 1984/85". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "First-class bowling for England – England in India 1984/85". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Statistics / Statsguru / JP Agnew / One-Day Internationals". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "India v England – Charminar Challenge Cup 1984/85 (4th ODI)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "India v England – Charminar Challenge Cup 1984/85 (5th ODI)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Australia v England – Benson and Hedges World Championship of Cricket 1984/85 (Group A)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Test bowling for England – England in India, Sri Lanka and Australia 1984/85". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ^ "England v Australia, 1985". ESPNcricinfo. 6 July 2008. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ^ "England v Australia in 1985 – Australia in British Isles 1985 (3rd Test)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Jonathan Agnew from 1985 to 1985". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Leicestershire v Kent". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "England v Australia in 1985 – Australia in British Isles 1985 (4th Test)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ Hopps, David (6 September 2005). "A swinging success that provides the perfect precedent". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 55

- ^ "Hitting the Seam – issue 3" (PDF). England and Wales Cricket Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ Scott, Les (31 August 2011). Bats, Balls: The Essential Cricket Book. Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-593-06146-6. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Bowling in the Brtiannic Assurance County Championship 1987 (ordered by wickets)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Bowling in Britannic Assurance County Championship 1988 (ordered by wickets)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. pp. 55–56

- ^ a b "Britannic Assurance County Championship 1990". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Williamson, Martin. "Jonathan Agnew". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Pittard, Steve (May 2006). "The XI last-minute call-ups". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ Frindall, Bill (2009). Ask Bearders. BBC Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84607-880-4.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 39

- ^ Bateman, Colin (1993). If The Cap Fits. Tony Williams Publications. p. 9. ISBN 1-869833-21-X.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 56

- ^ a b Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 61

- ^ a b "Jonathan Agnew". BBC Sport. 30 October 2006. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 66

- ^ a b Agnew. Aggers' Ashes, p. 249

- ^ Steen, Rob (31 July 2007). Sports journalism: a multimedia primer. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-415-39423-9. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Williamson, Andrea (22 November 2010). "The 2010/11 Ashes Series". Australia: ABC radio. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ a b Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 30

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 31

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. pp. 31–32

- ^ "International Cricket Captain". Gamespy. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Brian Lara returns to videogames". VideoGamer.com. 3 February 2005. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Laughlin, Andrew (23 December 2010). "Sky sells 'Wisden Cricketer' to consortium". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Wisden Cricketer magazine sold". ESPNcricinfo. 23 December 2010. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "'Aggers' feels an honorary degree of pride". Leicester Mercury. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2024 – via Newsbank.

- ^ "Lord Robert Winston among those to be honoured by Loughborough University". Loughborough University. 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Rio 2016: BBC commentator Jonathan Agnew swaps cricket for equestrian". BBC Sport. 29 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "BBC pay 2022-2023: The full list of star salaries". BBC News. 11 July 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "No. 61389". The London Gazette. 23 October 2015. p. 19950.

- ^ "No. 61803". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2016. p. N15.

- ^ https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/cricket/articles/c33ev3k3v6jo

- ^ a b c d Pringle, Derek (24 February 2001). "BBC commentary team refuses to be stumped by Sri Lanka test ban". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Leonard, Tom (24 February 2001). "Test match lock-out fails to stump BBC". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Angus Fraser (29 November 2004). "Someone needs to question cricket's whiter than whites." The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Atherton, Michael (4 August 2008). "Michael Vaughan bows out with dignity intact". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ Illingworth, Ray; Bannister, Jack (1996). One-Man Committee: The controversial reign of England's cricket supremo. London: Headline Book Publishing. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-7472-1515-4.

- ^ a b c Norrish, Mike (25 August 2009). "Lily Allen defends Jonathan Agnew over 'pervert' slur". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Buckley, Will (23 August 2009). "When Aggers met Lily: an unrequited love affair for the middle-aged". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Funny old game – Super bloopers". BBC News. 11 October 2001. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "The Tuffers and Vaughan Cricket Show". BBC Radio 5. BBC. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Johnston, Barry (27 May 2010). The Wit of Cricket. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-4447-1502-6. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Sporting kiss and tell's". The Observer. London. 8 May 2005. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ a b Pettle, Andrew (22 October 2010). "Jonathan Agnew on Johnners". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ name="legwin"/

- ^ a b c Agnew, Jonathan (1 August 2002). "How cricket ruined my own marriage ... just like Thorpe". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Former Notts County Cricket Club skipper Bicknell signs for Belvoir CC". Melton Times. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Agnew. Thanks, Johnners. p. 54

- ^ Harper, Tom (18 February 2013). "BBC's Aggers 'chose not to see daughters'". Standard.

- ^ Nikkhah, Roya (17 February 2013). "Jonathan Agnew: Divorced fathers have 'tough time'". Telegraph.

- ^ Agnew, Jonathan (27 July 2017). "How my Viking ancestry nearly cost me my hands". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Hunt, James. "Leicestershire in 1987". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (1988 ed.). John Wisden & Co. pp. 474–75.

- ^ a b Pringle, Derek (15 November 2007). "Heat is on for England in Sri Lanka". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "First-class bowling for England B – England in Sri Lanka 1985/86". The Cricketer. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Bannerman, Lucy (26 August 2013). "Life-or-death decision is one you have to make by yourself, says Jonathan Agnew". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Jonathan Agnew is subject of complaint to BBC over abusive tweets". The Guardian. 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "BBC cricket commentator Jonathan Agnew reprimanded over abusive messages". The Independent. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ Ronay, Barney (14 May 2019). "Put the smart phone down Aggers old chap. This spat really isn't cricket". The Guardian.

- 1960 births

- Living people

- BBC sports presenters and reporters

- D. B. Close's XI cricketers

- Deputy lieutenants of Leicestershire

- English cricket commentators

- English cricketers

- English male non-fiction writers

- England One Day International cricketers

- England Test cricketers

- English radio personalities

- English sportswriters

- Leicestershire cricketers

- Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers

- Members of the Order of the British Empire

- People educated at Uppingham School

- People from the Borough of Melton

- Cricketers from Leicestershire

- Cricketers from Macclesfield

- Wisden Cricketers of the Year