Equity (law)

In the field of jurisprudence, equity is the particular body of law, developed in the English Court of Chancery,[1] with the general purpose of providing legal remedies for cases wherein the common law is inflexible and cannot fairly resolve the disputed legal matter.[2] Conceptually, equity was part of the historical origins of the system of common law of England,[2] yet is a field of law separate from common law, because equity has its own unique rules and principles, and was administered by courts of equity.[2]

Equity exists in domestic law, both in civil law and in common law systems, and in international law.[1] The tradition of equity begins in antiquity with the writings of Aristotle (epieikeia) and with Roman law (aequitas).[1][3] Later, in civil law systems, equity was integrated in the legal rules, while in common law systems it became an independent body of law.[1]

Equity in common law jurisdictions (general)

[edit]In jurisdictions following the English common law system, equity is the body of law which was developed in the English Court of Chancery and which is now administered concurrently with the common law.[4] In common law jurisdictions, the word "equity" "is not a synonym for 'general fairness' or 'natural justice'", but refers to "a particular body of rules that originated in a special system of courts".[5]

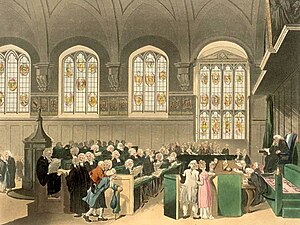

For much of its history, the English common law was principally developed and administered in the central royal courts: the Court of King's Bench, the Court of Common Pleas, and the Exchequer. Equity was the name given to the law which was administered in the Court of Chancery. The Judicature Acts of the 1870s effected a procedural fusion of the two bodies of law, ending their institutional separation. The reforms did not fuse the actual bodies of law however. As an example, this lack of fusion meant it was still not possible to receive an equitable remedy for a purely common law wrong. Judicial or academic reasoning which assumes the contrary has been described as a "fusion fallacy".[6]

Jurisdictions which have inherited the common law system differ in their treatment of equity. Over the course of the twentieth century some common law systems began to place less emphasis on the historical or institutional origin of substantive legal rules. In England and Wales, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, equity remains a distinct body of law. Modern equity includes, among other things:[6][7]

- the law relating to express, resulting, and constructive trusts;

- fiduciary law;

- equitable estoppel (including promissory and proprietary estoppel);

- relief against penalties and relief against forfeiture;[8]

- the doctrines of contribution, subrogation and marshalling; and

- equitable set-off.

Black's Law Dictionary, 10th ed., definition 4, differentiates "common law" (or just "law") from "equity".[9][10] Before 1873, England had two complementary court systems: courts of "law" which could only award money damages and recognized only the legal owner of property, and courts of "equity" (courts of chancery) that could issue injunctive relief (that is, a court order to a party to do something, give something to someone, or stop doing something) and recognized trusts of property. This split propagated to many of the colonies, including the United States. The states of Delaware, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee continue to have divided Courts of Law and Courts of Chancery. In New Jersey, the appellate courts are unified, but the trial courts are organized into a Chancery Division and a Law Division. There is a difference of opinion in Commonwealth countries as to whether equity and common law have been fused or are merely administered by the same court, with the orthodox view that they have not (expressed as rejecting the "fusion fallacy") prevailing in Australia,[11] while support for fusion has been expressed by the New Zealand Court of Appeal.[12]

For most purposes, the U.S. federal system and most states have merged the two courts.[13]

The latter part of the twentieth century saw increased debate over the utility of treating equity as a separate body of law. These debates were labelled the "fusion wars".[14][15] A particular flashpoint in this debate centred on the concept of unjust enrichment and whether areas of law traditionally regarded as equitable could be rationalised as part of a single body of law known as the law of unjust enrichment.[16][17][18]

History of equity in common law jurisdictions

[edit]After the Norman Conquest of England in the 11th century, royal justice came to be administered in three central courts: the Court of King's Bench, the Court of Common Pleas, and the Exchequer. The common law developed in these royal courts, which were created by the authority of the King of England, and whose jurisdiction over disputes between the King's subjects was based upon the King's writ.[19] Initially, a writ was probably a vague order to do right by the plaintiff,[19] and it was usually a writ of grace, issued at the pleasure of the King.[20]

During the 12th and 13th centuries, writ procedure gradually evolved into something much more rigid. All writs to commence actions had to be purchased by litigants from the Chancery, the head of which was the Lord Chancellor.[19] After writs began to become more specific and creative (in terms of the relief sought), Parliament responded in 1258 by providing in the Provisions of Oxford that the Chancellor could no longer create new writs without permission from the King and the King's Council (the curia regis).[19] Pursuant to this authorization,[19] litigants could purchase certain enumerated writs de cursu (as a matter of course) which later became known as writs ex debito justitiae (as a matter of right).[20] Each of these writs was associated with particular circumstances and led to a particular kind of judgment.[19] Procedure in the common law courts became tightly focused on the form of action (the particular procedure authorized by a particular writ to enforce a particular substantive right), rather than what modern lawyers would now call the cause of action (the underlying substantive right to be enforced).

Because the writ system was limited to enumerated writs for enumerated rights and wrongs, it sometimes produced unjust results. Thus, even though the King's Bench might have jurisdiction over a case and might have the power to issue the perfect writ, the plaintiff might still not have a case if there was not a single form of action combining them. Lacking a legal remedy, the plaintiff's only option would be to petition the King.

Litigants began to seek relief against unfair judgments of the common law courts by petitioning the King. Such petitions were initially processed by the King's Council, which itself was quite overworked, and the Council began to delegate the hearing of such petitions to the Lord Chancellor.[21] This delegation is often justified by the fact that the Lord Chancellor was literally the Keeper of the King's Conscience,[22][23] although Francis Palgrave argued that the delegation was initially driven by practical concerns and the moral justification came later.[21] The moral justification went as follows: as Keeper of the King's Conscience, the Chancellor "would act in particular cases to admit 'merciful exceptions' to the King's general laws to ensure that the King's conscience was right before God".[23] This concern for the King's conscience was then extended to the conscience of the defendant in Chancery, in that the Chancellor would intervene to prevent "unconscionable" conduct on the part of the defendant, in order to protect the conscience of the King.[23]

By the 14th century, it appears that Chancery was operating as a court, affording remedies for which the strict procedures of the common law worked injustice or provided no remedy to a deserving plaintiff. Chancellors often had theological and clerical training and were well versed in Roman law and canon law.[22][24] During this era, the Roman concept of aequitas influenced the development of the distinctly different but related English concept of equity: "The equity administered by the early English chancellors ... [was] confessedly borrowed from the aequitas and the judicial powers of the Roman magistrates."[22] By the 15th century, the judicial power of Chancery was clearly recognised.

Early Chancery pleadings vaguely invoked some sort of higher justice, such as with the formula "for the love of God and in way of charity".[25] During the 15th century, Chancery pleadings began to expressly invoke "conscience", to the point that English lawyers in the late 15th century thought of Chancery as a court of "conscience", not a court of "equity".[25] However, the "reasoning of the medieval chancellors has not been preserved" as to what they actually meant by the word "conscience",[26] and modern scholars can only indirectly guess at what the word probably meant.[27] The publication of the treatise The Doctor and Student in the early 16th century marked the beginning of Chancery's transformation from a court of conscience to a court of equity.[28]

Before that point in time, the word "equity" was used in the common law to refer to a principle of statutory interpretation derived from aequitas: the idea that written laws ought to be interpreted "according to the intention rather than the letter" of the law.[29] What was new was the application of the word "equity" to "the extraordinary form of justice administered by the chancellor", as a convenient way to distinguish Chancery jurisprudence from the common law.[29]

A common criticism of Chancery practice as it developed in the early medieval period was that it lacked fixed rules, varied greatly from Chancellor to Chancellor, and the Chancellor was exercising an unbounded discretion. The counterargument was that equity mitigated the rigour of the common law by looking to substance rather than to form.[citation needed]

The early chancellors were influenced by their training in theology and canon law, but the law of equity they applied was not canon law, but a new kind of law purportedly driven by conscience.[30] Whatever it meant in the medieval era, the word "conscience" clearly carried a subjective connotation (as it still does today).[30] Complaints about equity as an arbitrary exercise of conscience by nonlawyer Chancellors became quite frequent under the chancellorship of Thomas Wolsey (1515–1529), who "had no legal training, and delighted in putting down lawyers".[30]

In 1546, Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley, a nonlawyer, was accused of trying to inject the civil law into Chancery.[31] This was a "wild exaggeration", but as a result, the Crown began to transition away from clergy and nonlawyers and instead appointed only lawyers trained in the common law tradition to the position of Lord Chancellor (although there were six more nonlawyer chancellors in the decades after Wriothesley).[31] The last person without training in the common law before 2016 to serve as Lord Chancellor was Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who served briefly from 1672 to 1673.[31] (Liz Truss was appointed as Lord Chancellor in 2016, but this was after the position had been stripped of its judicial powers by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, leaving the Chancellor of the High Court as the highest judge sitting in equity in England and Wales.)

The development of a court of equity as a remedy for the rigid procedure of the common law courts meant it was inevitable that the two systems would come into conflict. Litigants would go "jurisdiction shopping" and often would seek an equitable injunction prohibiting the enforcement of a common law court order. The penalty for disobeying an equitable injunction and enforcing an unconscionable common law judgment was imprisonment.[23]

The 1615 conflict between common law and equity came about because of a "clash of strong personalities" between Lord Chancellor Ellesmere and the Chief Justice of the King's Bench, Sir Edward Coke.[31] Chief Justice Coke began the practice of issuing writs of habeas corpus that required the release of people imprisoned for contempt of chancery orders. This tension reached a climax in the Earl of Oxford's case (1615) where a judgment of Chief Justice Coke was allegedly obtained by fraud.[32] Chancellor Ellesmere issued an injunction from the Chancery prohibiting the enforcement of the common law order. The two courts became locked in a stalemate, and the matter was eventually referred to the Attorney General, Sir Francis Bacon. Sir Francis, by authority of King James I, upheld the use of the equitable injunction and concluded that in the event of any conflict between the common law and equity, equity would prevail.[33]

Chancery continued to be the subject of extensive criticism, the most famous of which was 17th-century jurist John Selden's aphorism:

Equity is a roguish thing: for law we have a measure, know what to trust to; equity is according to the conscience of him that is Chancellor, and as that is larger or narrower, so is equity. 'Tis all one as if they should make the standard for the measure we call a foot, a Chancellor's foot; what an uncertain measure would this be? One Chancellor has a long foot, another a short foot, a third an indifferent foot: 'tis the same thing in a Chancellor's conscience.[34]

After 1660, Chancery cases were regularly reported, several equitable doctrines developed, and equity started to evolve into a system of precedents like its common law cousin.[35] Over time, equity jurisprudence would gradually become a "body of equitable law, as complex, doctrinal, and rule-haunted as the common law ever was".[36]

One indicator of equity's evolution into a coherent body of law was Lord Eldon's response to Selden in an 1818 chancery case: "I cannot agree that the doctrines of this court are to be changed with every succeeding judge. Nothing would inflict on me greater pain, in quitting this place, than the recollection that I had done anything to justify the reproach that the equity of this court varies like the Chancellor's foot."[35][37]

Equity's primacy over common law in England was later enshrined in the Judicature Acts of the 1870s, which also served to fuse the courts of equity and the common law (although emphatically not the systems themselves) into one unified court system.

Statute of Uses 1535

[edit]One area in which the Court of Chancery assumed a vital role was the enforcement of uses, a role that the rigid framework of land law could not accommodate. This role gave rise to the basic distinction between legal and equitable interests.

In order to avoid paying land taxes and other feudal dues, lawyers developed a primitive form of trust called the "use" that enabled one person (who was not required to pay tax) to hold the legal title of the land for the use of another person. The effect of this trust was that the first person owned the land under the common law, but the second person had a right to use the land under the law of equity.

Henry VIII enacted the Statute of Uses in 1535 (which became effective in 1536) in an attempt to outlaw this practice and recover lost revenue. The Act effectively made the beneficial owner of the land the legal owner and therefore liable for feudal dues.

The response of the lawyers to this Statute was to create the "use upon a use". The Statute recognized only the first use, and so land owners were again able to separate the legal and beneficial interests in their land.

Comparison of equity traditions in common law countries

[edit]This article possibly contains original research. (November 2007) |

Australia

[edit]Equity remains a cornerstone of Australian private law. A string of cases in the 1980s saw the High Court of Australia re-affirm the continuing vitality of traditional equitable doctrines.[38] In 2009 the High Court affirmed the importance of equity and dismissed the suggestion that unjust enrichment has explanatory power in relation to traditional equitable doctrines such as subrogation.[39]

The state of New South Wales is particularly well known for the strength of its Equity jurisprudence. However, it was only in 1972 with the introduction of reform to the Supreme Court Act 1970 (NSW) that empowered both the Equity and Common Law Division of the Supreme Court of NSW to grant relief in either equity or common law.[40] In 1972 NSW also adopted one of the essential sections of the Judicature reforms, which emphasised that where there was a conflict between the common law and equity, equity would always prevail.[41] Nevertheless, in 1975 three alumni of Sydney Law School and judges of the NSW Supreme Court, Roddy Meagher, William Gummow and John Lehane produced Equity: Doctrines & Remedies. It remains one of the most highly regarded practitioner texts in Australia and England.[42][43] The work is now in its 5th edition and edited by Dyson Heydon, former Justice of the High Court, Justice Mark Leeming of the New South Wales Court of Appeal, and Dr Peter Turner of Cambridge University.[6]

United Kingdom

[edit]England and Wales

[edit]Equity remains a distinct part of the law of England and Wales. The main challenge to it has come from academic writers working within the law of unjust enrichment. Scholars such as Peter Birks and Andrew Burrows argue that in many cases the inclusion of the label "legal" or "equitable" before a substantive rule is often unnecessary.[15] Many English universities, such as Oxford and Cambridge, continue to teach Equity as a standalone subject. Leading practitioner texts include Snell's Equity, Lewin on Trusts, and Hayton & Underhill's Law of Trusts and Trustees.

Limits on the power of equity in English law were clarified by the House of Lords in The Scaptrade case (Scandinavian Trading Tanker Co. A.B. v Flota Petrolera Ecuatoriana [1983] 2 AC 694, 700), where the notion that the court's jurisdiction to grant relief was "unlimited and unfettered" (per Lord Simon of Glaisdale in Shiloh Spinners Ltd v. Harding [1973] A.C. 691, 726) was rejected as a "beguiling heresy".[44]

Scotland

[edit]The courts of Scotland have never recognised a division between the normal common law and equity, and as such the Court of Session (the supreme civil court of Scotland) has exercised an equitable and inherent jurisdiction and called the nobile officium.[45] The nobile officium enables the Court to provide a legal remedy where statute or the common law are silent, and prevent mistakes in procedure or practice that would lead to injustice. The exercise of this power is limited by adherence to precedent, and when legislation or the common law already specify the relevant remedy. Thus, the Court cannot set aside a statutory power, but can deal with situations where the law is silent, or where there is an omission in statute. Such an omission is sometimes termed a casus improvisus.[46][47]

India

[edit]In India the common law doctrine of equity had traditionally been followed even after it became independent in 1947. However, in 1963 the Specific Relief Act was passed by the Parliament of India following the recommendation of the Law Commission of India and repealing the earlier "Specific Relief Act" of 1877. Under the 1963 Act, most equitable concepts were codified and made statutory rights, thereby ending the discretionary role of the courts to grant equitable reliefs. The rights codified under the 1963 Act were as under:

- Recovery of possession of immovable property (ss. 5–8)

- Specific performance of contracts (ss. 9–25)

- Rectification of instruments (s. 26)

- Recession of contracts (ss. 27–30)

- Cancellation of instruments (ss. 31–33)

- Declaratory decrees (ss. 34–35)

- Injunctions (ss. 36–42)

With this codification, the nature and tenure of the equitable reliefs available earlier have been modified to make them statutory rights and are also required to be pleaded specifically to be enforced. Further to the extent that these equitable reliefs have been codified into rights, they are no longer discretionary upon the courts or as the English law has it, "Chancellor's foot" but instead are enforceable rights subject to the conditions under the 1963 Act being satisfied. Nonetheless, in the event of situations not covered under the 1963 Act, the courts in India continue to exercise their inherent powers in terms of Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, which applies to all civil courts in India.

There is no such inherent powers with the criminal courts in India except with the High Courts in terms of Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Further, such inherent powers are vested in the Supreme Court of India in terms of Article 142 of the Constitution of India which confers wide powers on the Supreme Court to pass orders "as is necessary for doing complete justice in any cause of matter pending before it".

United States

[edit]In modern practice, perhaps the most important distinction between law and equity is the set of remedies each offers. The most common civil remedy a court of law can award is monetary damages. Equity, however, enters injunctions or decrees directing someone either to act or to forbear from acting. Often, this form of relief is in practical terms more valuable to a litigant; for example, a plaintiff whose neighbor will not return his only milk cow, which had wandered onto the neighbor's property, may want that particular cow back, not just its monetary value. However, in general, a litigant cannot obtain equitable relief unless there is "no adequate remedy at law"; that is, a court will not grant an injunction unless monetary damages are an insufficient remedy for the injury in question. Law courts can also enter certain types of immediately enforceable orders, called "writs" (such as a writ of habeas corpus), but they are less flexible and less easily obtained than an injunction.

Another distinction is the unavailability of a jury in equity: the judge is the trier of fact. In the American legal system, the right of jury trial in civil cases tried in federal court is guaranteed by the Seventh Amendment in Suits at common law, cases that traditionally would have been handled by the law courts. The question of whether a case should be determined by a jury depends largely on the type of relief the plaintiff requests. If a plaintiff requests damages in the form of money or certain other forms of relief, such as the return of a specific item of property, the remedy is considered legal, and a jury is available as the fact-finder. On the other hand, if the plaintiff requests an injunction, declaratory judgment, specific performance, modification of contract, or some other non-monetary relief, the claim would usually be one in equity.

Thomas Jefferson explained in 1785 that there are three main limitations on the power of a court of equity: "If the legislature means to enact an injustice, however palpable, the court of Chancery is not the body with whom a correcting power is lodged. That it shall not interpose in any case which does not come within a general description and admit of redress by a general and practicable rule."[48] The US Supreme Court, however, has concluded that courts have wide discretion to fashion relief in cases of equity. The first major statement of this power came in Willard v. Tayloe, 75 U.S. 557 (1869). The Court concluded that "relief is not a matter of absolute right to either party; it is a matter resting in the discretion of the court, to be exercised upon a consideration of all the circumstances of each particular case."[49] Willard v. Tayloe was for many years the leading case in contract law regarding intent and enforcement.[50][51] as well as equity.[50][52]

In the United States, the federal courts and most state courts have merged law and equity into courts of general jurisdiction, such as county courts. However, the substantive distinction between law and equity has retained its old vitality.[53] This difference is not a mere technicality, because the successful handling of certain law cases is difficult or impossible unless a temporary restraining order (TRO) or preliminary injunction is issued at the outset, to restrain someone from fleeing the jurisdiction taking the only property available to satisfy a judgment, for instance. Furthermore, certain statutes like the Employee Retirement Income Security Act specifically authorize only equitable relief, which forces American courts to analyze in lengthy detail whether the relief demanded in particular cases brought under those statutes would have been available in equity.[54]

Equity courts were widely distrusted in the northeastern United States following the American Revolution. A serious movement for merger of law and equity began in the states in the mid-19th century, when David Dudley Field II convinced New York State to adopt what became known as the Field Code of 1848.[55][56] The federal courts did not abandon the old law/equity separation until the promulgation of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in 1938.

Three states still have separate courts for law and equity: Delaware, whose Court of Chancery is where most cases involving Delaware corporations (which includes a disproportionate number of multi-state corporations) are decided; Mississippi; and Tennessee.[57] However, merger in some states is less than complete; some other states (such as Illinois and New Jersey) have separate divisions for legal and equitable matters in a single court. Virginia had separate law and equity dockets (in the same court) until 2006.[58] Besides corporate law, which developed out of the law of trusts, areas traditionally handled by chancery courts included wills and probate, adoptions and guardianships, and marriage and divorce. Bankruptcy was also historically considered an equitable matter; although bankruptcy in the United States is today a purely federal matter, reserved entirely to the United States Bankruptcy Courts by the enactment of the United States Bankruptcy Code in 1978, bankruptcy courts are still officially considered "courts of equity" and exercise equitable powers under Section 105 of the Bankruptcy Code.[59]

After US courts merged law and equity, American law courts adopted many of the procedures of equity courts. The procedures in a court of equity were much more flexible than the courts at common law. In American practice, certain devices such as joinder, counterclaim, cross-claim and interpleader originated in the courts of equity.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Titi, Catharine (2021). The Function of Equity in International Law. Oxford University Press 2021. pp. 11ff. ISBN 9780198868002.

- ^ a b c Black, Henry Campbell (1891). A Law Dictionary, containing definitions of the terms and phrases of American and English jurisprudence, ancient and modern (second ed.). West Publishing Co. pp. 432–3. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ María José Falcón y Tella, Equity and Law (Peter Muckley tr, Martinus Nijhoff 2008)

- ^ 'Common law' here is used in its narrow sense, referring to that body of law principally developed in the superior courts of common law: King's Bench and Common Pleas.

- ^ Farnsworth, E. Allan (2010). Sheppard, Steve (ed.). An Introduction to the Legal System of the United States (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780199733101. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Heydon, J. D.; Leeming, M. J.; Turner, P. G. (2014). Meagher, Gummow & Lehane's Equity: Doctrine and Remedies. Trusts, Wills and Probate Library (5th ed.). LexisNexis. ISBN 9780409332254.

- ^ McGhee, John, ed. (13 December 2017). Snell's Equity (33rd ed.). Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 9780414051607.

- ^ There is currently a divergence of opinion between the High Court of Australia and the Supreme Court of England on this point. In Australia, the continuing existence of the equitable jurisdiction to relieve against penalties has been confirmed: Andrews v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2012] HCA 30, 247 CLR 205. In England, this view was not adopted: Cavendish Square Holding BV v Talal El Makdessi [2015] UKSC 67.

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary – Common law (10th ed.). 2014. p. 334.

4. The body of law derived from law courts as opposed to those sitting in equity.

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (2001). A Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage (2nd, revised ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780195077698.

Second, with the development of equity and equitable rights and remedies, common law and equitable courts, procedure, rights, and remedies, etc., are frequently contrasted, and in this sense common law is distinguished from equity.

- ^ Harris v Digital Pulse Pty Ltd [2003] NSWCA 10 at [21]–[27] (Spigelman CJ), [132]–[178] (Mason P, dissenting), [353] (Heydon JA), (2003) 56 NSWLR 298, 306 (Spigelman CJ), 325–9 (Mason P, dissenting), 391–2 (Heydon JA)

- ^ Tilbury, Michael (2003). "Fallacy or Furphy?: Fusion in a Judicature World" (PDF). UNSW Law Journal. 26 (2).

- ^ Friedman, Lawrence Meir (2005). A History of American Law (3rd ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-8258-1.

- ^ Degeling, Simone; Edelman, James, eds. (October 2005). Equity in Commercial Law. Sydney: Lawbook Co. ISBN 0-455-22208-8..

- ^ a b For an example of the pro-fusionist view, see Andrew Burrows, Burrows, Andrew (1 March 2002), "We Do This At Common Law But That in Equity", Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 22 (1): 1–16, doi:10.1093/ojls/22.1.1, JSTOR 3600632.

- ^ Birks, Peter (13 January 2005). Unjust Enrichment. Clarendon Law Series (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199276981.

- ^ Burrows, Andrew (2 December 2010). The Law of Restitution (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199296521.

- ^ Virgo, Graham (13 August 2015). The Principles of the Law of Restitution (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198726388.

- ^ a b c d e f Kerly, Duncan Mackenzie (1890). An Historical Sketch of the Equitable Jurisdiction of the Court of Chancery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9.

- ^ a b Goodnow, Frank J. (1891). "The Writ of Certiorari". Political Science Quarterly. 6 (3): 493–536. doi:10.2307/2139490. JSTOR 2139490.

- ^ a b Plucknett, Theodore Frank Thomas (1956). A Concise History of the Common Law (2001 reprint of 5th ed.). Boston: Little, Brown & Company. p. 180. ISBN 9781584771371. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Burdick, William Livesey (1938). The Principles of Roman Law and Their Relation to Modern Law (2002 reprint ed.). The Lawbook Exchange. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-58477-253-8.

- ^ a b c d Watt, Gary (2020). Trusts and Equity (9th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780198854142.

- ^ Worthington, Sarah (12 October 2006). Equity. Clarendon Law Series (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0199290504.

- ^ a b Klinck, Dennis R. (2010). Conscience, Equity and the Court of Chancery in Early Modern England. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 9781317161950. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ Klinck, Dennis R. (2010). Conscience, Equity and the Court of Chancery in Early Modern England. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 9781317161950. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ Klinck, Dennis R. (2010). Conscience, Equity and the Court of Chancery in Early Modern England. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 9781317161950. Retrieved November 11, 2023. As the title implies, this source is a 314-page treatment of the history of the concept of conscience in the Court of Chancery, to the extent that such history can be inferred from surviving sources.

- ^ Klinck, Dennis R. (2010). Conscience, Equity and the Court of Chancery in Early Modern England. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 9781317161950. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Baker, John (2019). An Introduction to English Legal History (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 9780198812609. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c Baker, John (2019). An Introduction to English Legal History (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780198812609. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Baker, John (2019). An Introduction to English Legal History (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780198812609. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Earl of Oxford's Case, I Ch Rep I, 21 ER 485 (Court of Chancery 1615).

- ^ Watt, Gary (2020). Trusts and Equity (9th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780198854142.

- ^ J. Selden, Table Talk; quoted in Evans, Michael; Jack, R Ian, eds. (1984), Sources of English Legal and Constitutional History, Sydney: Butterworths, pp. 223–224, ISBN 0409493821

- ^ a b Baker, John (2019). An Introduction to English Legal History (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780198812609. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Powell, H. Jefferson (Summer 1993). "'Cardozo's Foot': The Chancellor's Conscience and Constructive Trusts". Law and Contemporary Problems. 56 (3): 7–27. doi:10.2307/1192175. JSTOR 1192175. At pp. 7-8.

- ^ Gee v Pritchard (1818) 2 Swan 402, 414.

- ^ See, e.g., Muschinski v Dodds [1985] HCA 78, 160 CLR 583.

- ^ Bofinger v Kingsway [2009] HCA 44.

- ^ Supreme Court Act 1970 (NSW) s 44

- ^ Law Reform (Law and Equity) Act 1972 (NSW) s 5

- ^ Cukurova Finance International Ltd v Alfa Telecom Turkey Ltd [2013] UKPC 20 at para. 20

- ^ Harris v Digital Pulse Pty Ltd [2003] NSWCA 10, 56 NSWLR 298

- ^ Lord Hoffman, in Union Eagle Limited v. Golden Achievement Limited (Hong Kong) [1997] UKPC 5, delivered 3 February 1997, accessed 13 July 2023

- ^ Thomson, Stephen (2015). The Nobile Officium: The Extraordinary Equitable Jurisdiction of the Supreme Courts of Scotland. Edinburgh: Avizandum. ISBN 978-1904968337.

- ^ "Nobile officium used to recognise English High Court orders due to statutory casus improvisus". The Nobile Officium. Retrieved 11 May 2017.[dead link]

- ^ White, J. R. C. (1981). "A Brief Excursion into the Scottish Legal System". Holdsworth Law Review. 6 (2). University of Birmingham: 155–161.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (November 1785). "To Philip Mazzei". Letter to Phillip Mazzei.

- ^ Willard v. Tayloe, 75 U.S. 557 (1869).

- ^ a b Dawson, John P. (January 1984). "Judicial Revision of Frustrated Contracts: The United States". Boston University Law Review. 64 (1): 32.

- ^ "Events Subsequent to the Contract As a Defence to Specific Performance". Columbia Law Review. 16 (5): 411. May 1916. doi:10.2307/1110409. JSTOR 1110409.

- ^ Renner, Shirley (1999). Inflation and the Enforcement of Contracts. New Horizons in Law and Economics. Cheltenham, England: Elgar. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84064-062-5.

- ^ See, e.g., Sereboff v. Mid Atlantic Medical Services, Inc., 547 US 356 (2006). (Roberts CJ for a unanimous court) (reviewing the scope of equitable relief as authorized by the ERISA statute).

- ^ Great-West Life & Annuity Ins. Co. v. Knudson, 534 US 204 (2002).

- ^ Laycock, Douglas (2002). Modern American Remedies: Cases and materials (3rd ed.). Aspen Press. p. 370. ISBN 0735524696.

- ^ Funk, Kellen (2015). "Equity without Chancery: The Fusion of Law and Equity in the Field Code of Civil Procedure, New York 1846–76". Journal of Legal History. 36 (2): 152–191. doi:10.1080/01440365.2015.1047560. S2CID 142977209. SSRN 2600201.

- ^ Sources that mention four states (e.g., Laycock 2002) generally include Arkansas, which abolished its separate chancery courts as of January 1, 2002. "Circuit Court". Arkansas Judiciary. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ Rules of the Supreme Court of Virginia, Rule 3:1. See also Bryson, W. H. (2006). "The Merger of Common-Law and Equity Pleading in Virginia". University of Richmond Law Review. 41: 77–82.

- ^ Hawes, Lesley Anne (January–February 2013). "Another Conflict in the Circuits Brewing Over Bankruptcy Court's Equitable Powers Under §105(a)". ABF Journal. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

References

[edit]For a history of equity in England, including the Statute of Uses 1535:

- Cockburn, Tina; Shirley, Melinda (14 November 2011). Equity in a Nutshell. Sydney: Lawbook Co. ISBN 978-0455228808.

- Cockburn, Tina; Harris, Wendy; Shirley, Melinda (2005). Equity & Trusts. Sydney: LexisNexis Butterworths. ISBN 0409321346.

For a general treatise on Equity, including a historical analysis:

- Worthington, Sarah (12 October 2006). Equity. Clarendon Law Series (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199290504.

For a brief outline of the maxims, doctrines and remedies developed under equity:

- Watt, Gary (29 March 2007). Todd & Watt's Cases and Materials on Equity and Trusts (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199203161.

External links

[edit]- Christopher St. Germain's Doctor and Student (1518) Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, the classic common law text on equity.

- Delaware Court of Chancery: Official site

- Equity and Trusts[permanent dead link] Hudson, Alastair, 5th edition, Routledge-Cavendish, London, 2007 ISBN 978-0-415-41847-8