Gender neutrality in Spanish

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Feminist language reform has proposed gender neutrality in languages with grammatical gender, such as Spanish. Grammatical gender in Spanish refers to how Spanish nouns are categorized as either masculine (often ending in -o) or feminine (often ending in -a). As in other Romance languages—such as Portuguese, to which Spanish is very similar—a group of both men and women, or someone of unknown gender, is usually referred to by the masculine form of a noun and/or pronoun. Advocates of gender-neutral language modification consider this to be sexist, and exclusive of gender non-conforming people.[1] They also stress the underlying sexism of words whose feminine form has a different, often less prestigious meaning.[2] Some argue that a gender neutral Spanish can reduce gender stereotyping, deconstructing sexist gender roles and discrimination in the workplace.[3]

Grammatical background

[edit]In Spanish, the masculine is often marked with the suffix -o, and it is generally easy to make a feminine noun from a masculine one by changing the ending from o to a: cirujano, cirujana (surgeon; m./f.); médico, médica (physician, m./f.) If the masculine version ends with a consonant, the feminine is typically formed by adding an -a to it as well: el doctor, la doctora. However, not all nouns ending in -o are masculine, and not all nouns ending in -a are feminine:

- Singular nouns ending in -o or -a are epicene (invariable) in some cases: testigo (witness, any gender).

- Nouns with the epicene ending -ista, such as dentista, ciclista, turista, especialista (dentist, cyclist, tourist, specialist; either male or female) are almost always invariable. One exception is modisto (male fashion designer), which was created as a counterpart to modista (fashion designer, or clothes maker).

- Some nouns ending in -a refer only to men: cura ("priest") ends in -a but is grammatically masculine, for a profession held in Roman Catholic tradition only by men.

Invariable words in Spanish are often derived from the Latin participles ending in -ans and -ens (-antem and -entem in the accusative case): estudiante. Some words that are normatively epicene can have an informal feminine ending with '-a'. Example: la jefe; jefa. The same happens with la cliente (client); "la clienta".

The syntactic case of what is commonly referred to as masculine has been shown to primarily fulfill the role of gender neutrality within the language; the name masculine is inherited from Latin, but does not reflect the broader utility of the grammatical structure relevant to social gender. "Any lexical item subcategorized for gender will be specified, for example, as being feminine or it will carry no gender specification at all."[4]

Social aspects

[edit]Activists against sexism in language are also concerned about words whose feminine form has a different (usually less prestigious) meaning:

- An ambiguous case is "secretary": a secretaria is an attendant for her boss or a typist, usually female, while a secretario is a high-rank position—as in secretario general del partido comunista, "secretary general of the communist party"—usually held by males. With the access of women to positions labelled as "secretary general" or similar, some have chosen to use the masculine gendered la secretario and others have to clarify that secretaria is an executive position, not a subordinate one.[citation needed]

- Another example is hombre público, which translates literally to "public man", but means politician in Spanish, while mujer pública or "public woman" means prostitute.[2]

One study, conducted in 2014, looked at Spanish students' perception of gender roles in the information and communication technology field. As predicted, the study revealed that male and female Spanish students alike view ICT as a male-dominated field. This could correlate to the use of gender in Spanish language, including the use of masculine nouns in many historically male-dominated fields (see examples above).[5]

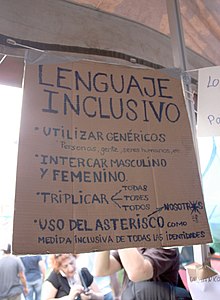

Reform proposals

[edit]In Spanish, as in other Romance languages, it is traditional to use the masculine form of nouns and pronouns when referring to both men and women. Advocates of gender-neutral language modification consider this to be sexist and favor new ways of writing and speaking. One such way is to replace gender-specific word endings -o and -a by an -x (such as in Latinx, as opposed to Latino and Latina[6]). It is more inclusive in genderqueer-friendly environments than the at-sign, given the existence of gender identities like agender and demigender and/or the existence of gender-abolitionist people. One argument is that the at-sign and related symbols are based on the idea that there is a gender binary, instead of trying to break away with this construct, among others.[7]

A list of proposals for reducing the generic masculine follows, adapted from the Asociación de Estudios Históricos sobre la Mujer's 2002 book, Manual de Lenguaje Administrativo no Sexista:[8]

| Method | Standard Spanish | Reformed Spanish | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collective noun | los trabajadores | la plantilla de la empresa | "the staff of the company" instead of "the workers" |

| Periphrasis | los políticos | la clase política | "the political class" instead of "the politicians" |

| Metonymy | los gerentes | la gerencia | "the management" instead of "the directors" |

| Splitting | los trabajadores | los trabajadores y las trabajadoras | literally "the (male) workers and the (female) workers" |

| Slash | impreso para el cliente | impreso para el/la cliente/a | literally "printed for the (male) client/the (female) client" |

| Apposition | El objetivo es proporcionar a los jóvenes una formación plena. | El objetivo es proporcionar a los jóvenes, de uno y otro sexo, una formación plena. | literally "The objective is to provide the youth, of one and the other sex, a full training." |

| Drop articles | Podrán optar al concurso los profesionales con experiencia. | Podrán optar al concurso profesionales con experiencia. | literally "Professionals with experience can apply for the competition." |

| Switch determiner | todos los miembros recibirán | cada miembro recibirá | "each member will receive" instead of "all of the members will receive". |

| Impersonal passive voice | Los jueces decidirán | Se decidirá judicialmente | "It will be decided judicially" instead of "The judges will decide" |

| Drop subject | Si el usuario decide abandonar la zona antes de lo estipulado, debe advertirlo. | Si decide abandonar la zona antes de lo estipulado, debe advertirlo | literally "If it is decided to leave the zone before the stipulated time, notice should be given" |

| Impersonal verb | Es necesario que el usuario preste más atención | Es necesario prestar más atención | literally "it is necessary to pay more attention" |

In recent decades, the most popular of gender neutral reform proposals have been splitting and the use of collective nouns, because neither deviate from Spanish grammar rules. They don't sound awkward in speech, so they are more widely accepted and used than the other examples listed above.[9]

Work by Ártemis López distinguishes between Indirect Non-binary Language (INL) and Direct Non-binary Language (DNL) in Spanish.[10] Indirect Non-binary Language utilizes many of the tactics listed above, such as using collective nouns, dropping the subject, or using metonymy in ways that avoid use of gender in the sentences.[11] Direct Non-binary Language, however, uses neologisms and neomorphemes to "accurately reflect the non-binary reality of the world"[12][13]

Pronouns

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

Some Spanish-speaking people advocate for the use of the pronouns elle (singular) and elles (plural).[14] Spanish often uses -a and -o for gender agreement in adjectives corresponding with feminine and masculine nouns, respectively; in order to agree with a gender neutral or non-binary noun, it is suggested to use the suffix -e.[15][16] This proposal is both to include people who identify as nonbinary and to remove the perceived default in the language as masculine.

Replacing -a and -o

[edit]There are several proposed word endings that combine the masculine -o and the feminine -a.

Writing

[edit]| Sign | Sign comment | Ref | Example | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ | at-sign, U+0040 | [17] | l@s niñ@s | ||

| Ⓐ | anarchist circled A U+24B6 | [18] | lⒶs niñⒶs | especially in radical political writing: ¡Acción DirectⒶ! [19] | |

| x | [6][20] | lxs niñxs | The ending -x is often used to be inclusive of non-binary genders when talking about mixed gender groups, particularly in the context of activist efforts: Latinx, Chicanx, etc. | ||

| e | [14] | les niñes |

The use of -e instead of the gender-informing suffix (when masculinity is not implied by the use of the -e suffix itself)[14] |

Pronunciation

[edit]An argument used against both the use of the at-sign as a letter and the use of -x for gender-neutral endings is that the resulting words are rendered unpronounceable. It is also argued that these endings, while attempting to be inclusive in regard to gender identity, would exclude people who, due to being visually impaired, illiterate, or having a disability such as ADHD or dyslexia, rely on screen readers. However, it has been proposed that using -e instead would solve the issue, as the resulting words would be easily pronounced.[21][22]

The Diccionario panhispánico de dudas, published by the Real Academia Española, says that the at-sign is not a linguistic sign, and should not be used from a normative point of view.[17]

Political use

[edit]Some politicians have begun to avoid perceived sexism in their speeches; the Mexican president Vicente Fox Quesada, for example, commonly repeated gendered nouns in their masculine and feminine versions (ciudadanos y ciudadanas). This way of speaking is subject to parodies where new words with the opposite ending are created for the sole purpose of contrasting with the gendered word traditionally used for the common case (like felizas and especialistos in felices y felizas or las y los especialistas y especialistos).

There remain a few cases where the appropriate gender is uncertain:

- Presidenta used to be "the president's wife", but there have been several female presidents in Latin American republics, and in modern usage the word generally means a female president. Some feel that presidente can be treated as invariable, as it ends in -ente, but others prefer to use a different feminine form.[23] The usage is inconsistent: clienta is often used for female customers, but *cantanta is never used for female singers.

- El policía (the policeman). Since la policía means "the police force", the only productive feminine counterpart is la mujer policía (the police woman).[24] A similar case is música (meaning both "music" and "female musician").

- Juez ("male judge"). Many judges in Spanish-speaking countries are women. Since the ending of juez is uncommon in Spanish, some prefer being called la juez while others have created the neologism jueza.[25]

In popular culture

[edit]The Spanish-language version of the video game Spider-Man 2, released in 2023, used gender-neutral language to refer to a nonbinary character (example: Primero quiero que conozcas a le doctore Young, une importante entomólogue). This usage was controversial among players and streamers against inclusive language.[26][27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schmidt, Samantha (December 5, 2019). "A Language for All". Washington Post.

- ^ a b Miño, Rodrigo (June 6, 2018). ""Hombre Público" vs "Mujer pública": Polémica Genera Diferencia de Significado en la RAE". Meganoticias.

- ^ Sczesny, Sabine; Formanowicz, Magda; Moser, Franziska (February 2, 2016). "Can Gender-Fair Language Reduce Gender Stereotyping and Discrimination?". Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 25. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00025. PMC 4735429. PMID 26869947 – via Gale.

- ^ Prado, Marcial. & Linguistic Research, Inc., Edmonton (Alberta). (1978). Markedness and the Gender Feature in Spanish. [Washington, D.C.] : Distributed by ERIC Clearinghouse

- ^ Sáinz, Milagros; Meneses, Julio; López, Beatriz-Soledad; Fàbregues, Sergi (2016-02-01). "Gender Stereotypes and Attitudes Towards Information and Communication Technology Professionals in a Sample of Spanish Secondary Students". Sex Roles. 74 (3): 154–168. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0424-2. ISSN 1573-2762. S2CID 145486816.

- ^ a b "Definition of Latinx in English". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Miniguide for the linguistic guerrillerx – Revista Geni (in Portuguese)

- ^ Lomotey, Benedicta Adokarley (2011). "On Sexism in Language and Language Change – The Case of Peninsular Spanish". Linguistik Online. 70 (1). doi:10.13092/lo.70.1748. ISSN 1615-3014.

- ^ Nissen, Uwe Kjaer (January 1, 2013). "Is Spanish becoming more gender fair? A historical perspective on the interpretation of gender-specific and gender-neutral expressions". Linguistik Online. 58. doi:10.13092/lo.58.241 – via Gale.

- ^ "The Vocal Fries – Use People's Pronouns – 57:53". radiopublic.com. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ "Guest post: Non-binary and inclusive language in translation". Training for Translators. 2019-03-11. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ "My Research". Ártemis López. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ "Lenguaje no binario. Ártemís López". RTVE.es (in Spanish). 2021-03-19. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ a b c Building a neuter gender in Spanish – for a more feminist, egalitarian and inclusive language Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)[1]

- ^ "Youngstown State University, Africana Studies". African Studies Companion Online. doi:10.1163/_afco_asc_1828. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ Bonnin, Juan Eduardo; Coronel, Alejandro Anibal (2021-03-15). "Attitudes Toward Gender-Neutral Spanish: Acceptability and Adoptability". Frontiers in Sociology. 6: 629616. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2021.629616. ISSN 2297-7775. PMC 8022528. PMID 33869578.

- ^ a b "género". Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. Real Academia Española. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Agitando lo cotidiano. Una conversación sobre el desafío Ⓐnarquista frente al sexismo en el lenguaje – LL Journal". Archived from the original on 2021-04-28. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ^ "Agitando lo cotidiano. Una conversación sobre el desafío Ⓐnarquista frente al sexismo en el lenguaje – LL Journal". Archived from the original on 2022-04-16. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ "Declaración por la libertad de los presos de Atenco. Campaña Primero Nuestrxs Presxs". Enlace Zapatista (in Spanish). 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ^ Dana, Agustín (8 August 2020). "Lenguaje Inclusivo, Accesibilidad y la Equis". medium.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ ""Chicxs" y "maestr@s" ¿el lenguaje inclusivo de los jóvenes en las redes sociales se trasladará a las aulas?". Infobae (in Spanish). 15 January 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Cristina Kirchner corrigió al senador Mayans que la llamó "presidente" durante el debate por la emergencia económica". Todo Noticias (in Spanish). Artear. 20 December 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "La mujer Policía, madre, esposa y garante de la seguridad ciudadana". Ministerio de Gobierno de la República del Ecuador.

- ^ "El juez/ la jueza". SpanishDict.

- ^ Olmos, Fernando Guarneros (2023-11-14). "Spider-Man 2, un juego inclusivo a pesar de las críticas e intolerancia". Expansión (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-11-20.

- ^ H., Liliana Carmona (23 October 2023). "Videojuego de Spider-Man se hace viral por usar lenguaje inclusivo; streamers se quejan".