Mesolithic

Reconstruction of a "temporary" Mesolithic house in Ireland; waterside sites offered good food resources. | |

| Alternative names | Epipaleolithic (for the Near East) |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Europe |

| Period | Middle of Stone Age |

| Dates | 20,000 to 10,000 BP (Middle East) 15,000–5,000 BP (Europe) |

| Preceded by | Upper Paleolithic |

| Followed by | Neolithic |

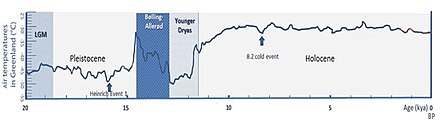

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, mesos 'middle' + λίθος, lithos 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus. The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia. It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in Europe and the Middle East, between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. In Europe it spans roughly 15,000 to 5,000 BP; in the Middle East (the Epipalaeolithic Near East) roughly 20,000 to 10,000 BP. The term is less used of areas farther east, and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa.

The type of culture associated with the Mesolithic varies between areas, but it is associated with a decline in the group hunting of large animals in favour of a broader hunter-gatherer way of life, and the development of more sophisticated and typically smaller lithic tools and weapons than the heavy-chipped equivalents typical of the Paleolithic. Depending on the region, some use of pottery and textiles may be found in sites allocated to the Mesolithic, but generally indications of agriculture are taken as marking transition into the Neolithic. The more permanent settlements tend to be close to the sea or inland waters offering a good supply of food. Mesolithic societies are not seen as very complex, and burials are fairly simple; in contrast, grandiose burial mounds are a mark of the Neolithic.

Terminology

The terms "Paleolithic" and "Neolithic" were introduced by John Lubbock in his work Pre-historic Times in 1865. The additional "Mesolithic" category was added as an intermediate category by Hodder Westropp in 1866. Westropp's suggestion was immediately controversial. A British school led by John Evans denied any need for an intermediate: the ages blended together like the colors of a rainbow, he said. A European school led by Gabriel de Mortillet asserted that there was a gap between the earlier and later.

Edouard Piette claimed to have filled the gap with his naming of the Azilian Culture. Knut Stjerna offered an alternative in the "Epipaleolithic", suggesting a final phase of the Paleolithic rather than an intermediate age in its own right inserted between the Paleolithic and Neolithic.

By the time of Vere Gordon Childe's work, The Dawn of Europe (1947), which affirms the Mesolithic, sufficient data had been collected to determine that a transitional period between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic was indeed a useful concept.[2] However, the terms "Mesolithic" and "Epipalaeolithic" remain in competition, with varying conventions of usage. In the archaeology of Northern Europe, for example for archaeological sites in Great Britain, Germany, Scandinavia, Ukraine, and Russia, the term "Mesolithic" is almost always used. In the archaeology of other areas, the term "Epipaleolithic" may be preferred by most authors, or there may be divergences between authors over which term to use or what meaning to assign to each. In the New World, neither term is used (except provisionally in the Arctic).

"Epipaleolithic" is sometimes also used alongside "Mesolithic" for the final end of the Upper Paleolithic immediately followed by the Mesolithic.[3] As "Mesolithic" suggests an intermediate period, followed by the Neolithic, some authors prefer the term "Epipaleolithic" for hunter-gatherer cultures who are not succeeded by agricultural traditions, reserving "Mesolithic" for cultures who are clearly succeeded by the Neolithic Revolution, such as the Natufian culture. Other authors use "Mesolithic" as a generic term for hunter-gatherer cultures after the Last Glacial Maximum, whether they are transitional towards agriculture or not. In addition, terminology appears to differ between archaeological sub-disciplines, with "Mesolithic" being widely used in European archaeology, while "Epipalaeolithic" is more common in Near Eastern archaeology.

Europe

The Balkan Mesolithic begins around 15,000 years ago. In Western Europe, the Early Mesolithic, or Azilian, begins about 14,000 years ago, in the Franco-Cantabrian region of northern Spain and Southern France. In other parts of Europe, the Mesolithic begins by 11,500 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), and it ends with the introduction of farming, depending on the region between c. 8,500 and 5,500 years ago. Regions that experienced greater environmental effects as the last glacial period ended have a much more apparent Mesolithic era, lasting millennia.[4] In northern Europe, for example, societies were able to live well on rich food supplies from the marshlands created by the warmer climate. Such conditions produced distinctive human behaviors that are preserved in the material record, such as the Maglemosian and Azilian cultures. Such conditions also delayed the coming of the Neolithic until some 5,500 BP in northern Europe.

The type of stone toolkit remains one of the most diagnostic features: the Mesolithic used a microlithic technology – composite devices manufactured with Mode V chipped stone tools (microliths), while the Paleolithic had utilized Modes I–IV. In some areas, however, such as Ireland, parts of Portugal, the Isle of Man and the Tyrrhenian Islands, a macrolithic technology was used in the Mesolithic.[5] In the Neolithic, the microlithic technology was replaced by a macrolithic technology, with an increased use of polished stone tools such as stone axes.

There is some evidence for the beginning of construction at sites with a ritual or astronomical significance, including Stonehenge, with a short row of large post holes aligned east–west, and a possible "lunar calendar" at Warren Field in Scotland, with pits of post holes of varying sizes, thought to reflect the lunar phases. Both are dated to before c. 9,000 BP (the 8th millennium BC).[6]

An ancient chewed gum made from the pitch of birch bark revealed that a woman enjoyed a meal of hazelnuts and duck about 5,700 years ago in southern Denmark.[7][8] Mesolithic people influenced Europe's forests by bringing favored plants like hazel with them.[9]

As the "Neolithic package" (including farming, herding, polished stone axes, timber longhouses and pottery) spread into Europe, the Mesolithic way of life was marginalized and eventually disappeared. Mesolithic adaptations such as sedentism, population size and use of plant foods are cited as evidence of the transition to agriculture.[10] Other Mesolithic communities rejected the Neolithic package likely as a result of ideological reluctance, different worldviews and an active rejection of the sedentary-farming lifestyle.[11] In one sample from the Blätterhöhle in Hagen, it seems that the descendants of Mesolithic people maintained a foraging lifestyle for more than 2000 years after the arrival of farming societies in the area;[12] such societies may be called "Subneolithic". For hunter-gatherer communities, long-term close contact and integration in existing farming communities facilitated the adoption of a farming lifestyle. The integration of these hunter-gatherer in farming communities was made possible by their socially open character towards new members.[11] In north-Eastern Europe, the hunting and fishing lifestyle continued into the Medieval period in regions less suited to agriculture, and in Scandinavia no Mesolithic period may be accepted, with the locally preferred "Older Stone Age" moving into the "Younger Stone Age".[13]

Art

Compared to the preceding Upper Paleolithic and the following Neolithic, there is rather less surviving art from the Mesolithic. The Rock art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin, which probably spreads across from the Upper Paleolithic, is a widespread phenomenon, much less well known than the cave-paintings of the Upper Paleolithic, with which it makes an interesting contrast. The sites are now mostly cliff faces in the open air, and the subjects are now mostly human rather than animal, with large groups of small figures; there are 45 figures at Roca dels Moros. Clothing is shown, and scenes of dancing, fighting, hunting and food-gathering. The figures are much smaller than the animals of Paleolithic art, and depicted much more schematically, though often in energetic poses.[14] A few small engraved pendants with suspension holes and simple engraved designs are known, some from northern Europe in amber, and one from Star Carr in Britain in shale.[15] The Elk's Head of Huittinen is a rare Mesolithic animal carving in soapstone from Finland.

The rock art in the Urals appears to show similar changes after the Paleolithic, and the wooden Shigir Idol is a rare survival of what may well have been a very common material for sculpture. It is a plank of larch carved with geometric motifs, but topped with a human head. Now in fragments, it would apparently have been over 5 metres tall when made.[16] The Ain Sakhri figurine from Palestine is a Natufian carving in calcite.

A total of 33 antler frontlets have been discovered at Star Carr.[17] These are red deer skulls modified to be worn by humans. Modified frontlets have also been discovered at Bedburg-Königshoven, Hohen Viecheln, Plau, and Berlin-Biesdorf.[18]

-

The Ain Sakhri lovers; c. 9000 BCE (late Epipalaeolithic Near East); calcite; height: 10.2 cm, width: 6.3 cm; from Ain Sakhri (near Bethlehem, Palestine); British Museum (London)

-

Roca dels Moros, Spain, The Dance of Cogul, tracing by Henri Breuil

Weaving

Weaving techniques were deployed to create shoes and baskets, the latter being of fine construction and decorated with dyes. Examples have been found in Cueva de los Murciélagos in Southern Spain that in 2023 were dated to 9,500 years ago.[20][21]

Ceramic Mesolithic

In North-Eastern Europe, Siberia, and certain southern European and North African sites, a "ceramic Mesolithic" can be distinguished between c. 9,000 to 5,850 BP. Russian archaeologists prefer to describe such pottery-making cultures as Neolithic, even though farming is absent. This pottery-making Mesolithic culture can be found peripheral to the sedentary Neolithic cultures. It created a distinctive type of pottery, with point or knob base and flared rims, manufactured by methods not used by the Neolithic farmers. Though each area of Mesolithic ceramic developed an individual style, common features suggest a single point of origin.[22][citation needed] The earliest manifestation of this type of pottery may be in the region around Lake Baikal in Siberia. It appears in the Yelshanka culture on the Volga in Russia 9,000 years ago,[23][24] and from there spread via the Dnieper-Donets culture to the Narva culture of the Eastern Baltic. Spreading westward along the coastline it is found in the Ertebølle culture of Denmark and Ellerbek of Northern Germany, and the related Swifterbant culture of the Low Countries.[25][26]

A 2012 publication in the Science journal, announced that the earliest pottery yet known anywhere in the world was found in Xianrendong cave in China, dating by radiocarbon to between 20,000 and 19,000 years before present, at the end of the Last Glacial Period.[28][29] The carbon 14 datation was established by carefully dating surrounding sediments.[29][30] Many of the pottery fragments had scorch marks, suggesting that the pottery was used for cooking.[30] These early pottery containers were made well before the invention of agriculture (dated to 10,000 to 8,000 BC), by mobile foragers who hunted and gathered their food during the Late Glacial Maximum.[30]

Cultures

| Part of a series on |

| Human history and prehistory |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future (Holocene epoch) |

| The Mesolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Upper Paleolithic |

| ↓ Neolithic |

| Geographical range | Periodization | Culture | Temporal range | Notable sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southeastern Europe (Greece, Aegean) | Balkan Mesolithic | 15,000–7,000 BP | Franchthi, Theopetra[31] | |

| Southeastern Europe (Romania/Serbia) | Balkan Mesolithic | Iron Gates culture | 13,000–5,000 BP | Lepenski Vir[32] |

| Western Europe | Early Mesolithic | Azilian | 14,000–10,000 BP | |

| Northern Europe (Norway) | Fosna-Hensbacka culture | 12,000–10,500 BP | ||

| Northern Europe (Norway) | Early Mesolithic | Komsa culture | 12,000–10,000 BP | |

| Central Asia (Middle Urals) | 12,000–5,000 BP | Shigir Idol, Vtoraya Beregovaya[33] | ||

| Northeastern Europe (Estonia, Latvia and northwestern Russia) | Middle Mesolithic | Kunda culture | 10,500–7,000 BP | Lammasmägi, Pulli settlement |

| Northern Europe | Maglemosian culture | 11,000–8,000 BP | ||

| Western and Central Europe | Sauveterrian culture | 10,500–8,500 BP | ||

| Western Europe (Great Britain) | British Mesolithic | 11,000–6000 BP | Star Carr, Howick house, Gough's Cave, Cramond, Aveline's Hole | |

| Western Europe (Ireland) | Irish Mesolithic | 11,000–5,500 BP | Mount Sandel | |

| Western Europe (Belgium and France) | Tardenoisian culture | 10,000–5,000 BP | ||

| Central and Eastern Europe (Belarus, Lithuania and Poland) | Late Mesolithic | Neman culture | 9,000–5,000 BP | |

| Northern Europe (Scandinavia) | Nøstvet and Lihult cultures | 8,200–5,200 BP | ||

| Northern Europe (Scandinavia) | Kongemose culture | 8,000–7,200 BP | ||

| Northern Europe (Scandinavia) | Late Mesolithic | Ertebølle | 7,300–5,900 BP | |

| Western Europe (Netherlands) | Late Mesolithic | Swifterbant | 7,300–5,400 BP | |

| Western Europe (Portugal) | Late Mesolithic | 7,600–5,500 BP |

"Mesolithic" outside of The old world

While Paleolithic and Neolithic have been found useful terms and concepts in the archaeology of China, and can be mostly regarded as happily naturalized, Mesolithic was introduced later, mostly after 1945, and does not appear to be a necessary or useful term in the context of China. Chinese sites that have been regarded as Mesolithic are better considered as "Early Neolithic".[34]

In the archaeology of India, the Mesolithic, dated roughly between 12,000 and 8,000 BP, remains a concept in use.[35]

In the archaeology of the Americas, an Archaic or Meso-Indian period, following the Lithic stage, somewhat equates to the Mesolithic.

The Saharan rock paintings found at Tassili n'Ajjer in central Sahara, and at other locations depict vivid scenes of everyday life in central North Africa. Some of these paintings were executed by a hunting people who lived in a savanna region teeming with a water-dependent species like the hippopotamus, animals that no longer exist in the now-desert area.[36]

| Geographical range | Periodization | Culture | Temporal range | Notable sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Africa (Morocco) | Late Upper Paleolithic to Early Mesolithic | Iberomaurusian culture | 24,000–10,000 BP | |

| North Africa | Capsian culture | 12,000–8,000 BP | ||

| East Africa | Kenya Mesolithic | 8,200–7,400 BP | Gamble's cave[37] | |

| Central Asia (Middle Urals) | 12,000–5,000 BP | Shigir Idol, Vtoraya Beregovaya[38] | ||

| East Asia (Japan) | Jōmon cultures | 16,000–2,350 BP | ||

| East Asia (Korea) | Jeulmun pottery period | 10,000–3,500 BP | ||

| South Asia (India) | South Asian Stone Age | 12,000–4,000 BP[39] | Bhimbetka rock shelters, Lekhahia |

See also

- Caucasus hunter-gatherer

- History of archery#Prehistory

- List of Stone Age art

- List of Mesolithic settlements

- Mammoth extinction

- Eastern Hunter-Gatherer

- Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer

- Western Hunter-Gatherer

- Anatolian hunter-gatherers

- Younger Dryas

References

- ^ Zalloua, Pierre A.; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (6 January 2017). "Mapping Post-Glacial expansions: The Peopling of the middle east". Scientific Reports. 7: 40338. Bibcode:2017NatSR...740338P. doi:10.1038/srep40338. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5216412. PMID 28059138.

- ^ Linder, F. (1997). Social differentiering i mesolitiska jägar-samlarsamhällen. Uppsala.: Institutionen för arkeologi och antik historia, Uppsala universitet.

- ^ "final Upper Paleolithic industries occurring at the end of the final glaciation which appear to merge technologically into the Mesolithic" Bahn, Paul, ed. (2002). The Penguin archaeology guide. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-051448-3.

- ^ Conneller, Chantal; Bayliss, Alex; Milner, Nicky; Taylor, Barry (2016). "The Resettlement of the British Landscape: Towards a chronology of Early Mesolithic lithic assemblage types". Internet Archaeology. 42 (42). doi:10.11141/ia.42.12. hdl:10034/621138.

- ^ Driscoll, Killian (2006). The early prehistory in the west of Ireland: Investigations into the social archaeology of the Mesolithic, west of the Shannon, Ireland (Thesis). National University of Ireland, Galway.

- ^ V. Gaffney; et al. "Time and a Place: A luni-solar 'time-reckoner' from 8th millennium BC Scotland". Internet Archaeology. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Jensen, Theis Z. T.; Niemann, Jonas; Iversen, Katrine Højholt; Fotakis, Anna K.; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Vågene, Åshild J.; Pedersen, Mikkel Winther; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Ellegaard, Martin R.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Lanigan, Liam T. (17 December 2019). "A 5700 year-old human genome and oral microbiome from chewed birch pitch". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 5520. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.5520J. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13549-9. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6917805. PMID 31848342.

- ^ "5,700-Year-Old Lola, Her Genome Sequenced from Gum, Joins Other Named Forebears". DNA Science. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Paschall, Max (22 July 2020). "The Lost Forest Gardens of Europe". Shelterwood Forest Farm. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Price, Douglas, ed. (2000). Europe's first farmers. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521665728.

- ^ a b Furholt, Martin (2021). "Mobility and Social Change: Understanding the European Neolithic Period after the Archaeogenetic Revolution". Journal of Archaeological Research. 10.1007/s10814-020-09153-x (4): 481–535. doi:10.1007/s10814-020-09153-x. hdl:10852/85345.

- ^ Bollongino, R.; Nehlich, O.; Richards, M. P.; Orschiedt, J.; Thomas, M. G.; Sell, C.; Fajkosova, Z.; Powell, A.; Burger, J. (2013). "2000 Years of Parallel Societies in Stone Age Central Europe" (PDF). Science. 342 (6157): 479–81. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..479B. doi:10.1126/science.1245049. PMID 24114781. S2CID 206552000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2020.

- ^ Bailey, Geoff and Spikins, Penny, Mesolithic Europe, p. 4, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521855039, 978-0521855037

- ^ Sandars, Nancy K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), pp. 87–96, 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

- ^ "11,000 year old pendant is earliest known Mesolithic art in Britain", University of York

- ^ Geggel, Laura (25 April 2018). "This Eerie, Human-Like Figure Is Twice As Old As Egypt's Pyramids". Live Science. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Nicky Milner; Chantal Conneller; Barry Taylor (2018). STAR CARR Volume 1: a persistent place. White Rose University Press.

- ^ Martin Street; Markus Wil (2015). "Technological aspects of two Mesolithic red deer 'antler frontlets' from the German Rhineland". In N. Ashton; C. Harris (eds.). No Stone Unturned. Papers in Honour of Roger Jacobi. pp. 209–219.

- ^ Morgan, C.; Scholma-Mason, N. (2017). "Animated GIFs as Expressive Visual Narratives and Expository Devices in Archaeology". Internet Archaeology (44). doi:10.11141/ia.44.11.

- ^ Hunter-Gatherers Were Making Baskets 9,500 Years Ago, Researchers Say by Rachel Chaundler, The New York Times 30 September 2023 Science, updated 3 October 2023

- ^ Martínez-Sevilla, Francisco; Herrero-Otal, Maria; Martín-Seijo, María; Santana, Jonathan; Lozano Rodríguez, José A.; Maicas Ramos, Ruth; Cubas, Miriam; Homs, Anna; Martínez Sánchez, Rafael M.; Bertin, Ingrid; Barroso Bermejo, Rosa; Bueno Ramírez, Primitiva; de Balbín Behrmann, Rodrigo; Palomo Pérez, Antoni; Álvarez-Valero, Antonio M. (27 September 2023). "The earliest basketry in southern Europe: Hunter-gatherer and farmer plant-based technology in Cueva de los Murciélagos (Albuñol)". Science Advances. 9 (39): eadi3055. Bibcode:2023SciA....9I3055M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adi3055. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 10530072. PMID 37756397.

- ^ De Roevers, pp. 162–63

- ^ Anthony, D.W. (2007). "Pontic-Caspian Mesolithic and Early Neolithic societies at the time of the Black Sea Flood: a small audience and small effects". In Yanko-Hombach, V.; Gilbert, A.A.; Panin, N.; Dolukhanov, P.M. (eds.). The Black Sea Flood Question: changes in coastline, climate and human settlement. Springer. pp. 245–370. ISBN 978-9402404654.

- ^ Anthony, David W. (2010). The horse, the wheel, and language : how Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691148182.

- ^ Gronenborn, Detlef (2007). "Beyond the models: Neolithisation in Central Europe". Proceedings of the British Academy. 144: 73–98.

- ^ Detlef Gronenborn, Beyond the models: Neolithisation in Central Europe, Proceedings of the British Academy, vol. 144 (2007), pp. 73–98 (87).

- ^ Huan, Anthony (13 April 2019). "Ancient China: Neolithic". National Museum of China.

- ^ Stanglin, Douglas (29 June 2012). "Pottery found in China cave confirmed as world's oldest". USA Today.

- ^ a b Wu, X; Zhang, C; Goldberg, P; Cohen, D; Pan, Y; Arpin, T; Bar-Yosef, O (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. PMID 22745428. S2CID 37666548.

- ^ a b c Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428. S2CID 37666548.

- ^ Sarah Gibbens, "Face of 9,000-Year-Old Teenager Reconstructed", National Geographic, 19 January 2018.

- ^ Srejovic, Dragoslav (1972). Europe's First Monumental Sculpture: New Discoveries at Lepenski Vir. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-39009-2.

- ^ Central Asia does not enter the Neolithic, but transitions from the Mesolithic to the Chalcolithic in the fourth millennium BC (metmuseum.org). The early onset of the Mesolithic in Central Asia and its importance for later European mesolithic cultures was understood only after 2015, with the radiocarbon dating of the Shigor idol to 11,500 years old. N.E. Zaretskaya et al., "Radiocarbon chronology of the Shigir and Gorbunovo archaeological bog sites, Middle Urals, Russia", Proceedings of the 6th International Radiocarbon and Archaeology Symposium, (E Boaretto and N R Rebollo Franco eds.), RADIOCARBON Vol 54, No. 3–4, 2012, 783–94.

- ^ Zhang, Chi, The Mesolithic and the Neolithic in China (PDF), 1999, Documenta Praehistorica. Poročilo o raziskovanju paleolitika, neolotika in eneolitika v Sloveniji. Neolitske študije = Neolithic studies, [Zv.] 26 (1999), pp. 1–13 dLib

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen, Ancient Indian History and Civilization, p. 23, 1999, New Age International, ISBN 8122411983, 978-8122411980

- ^ "Tassili n'Ajjer". UNESCO.

- ^ "Africa-Paleolithic". Britannica. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Central Asia does not enter the Neolithic, but transitions from the Mesolithic to the Chalcolithic in the fourth millennium BC (metmuseum.org). The early onset of the Mesolithic in Central Asia and its importance for later European mesolithic cultures was understood only after 2015, with the radiocarbon dating of the Shigor idol to 11,500 years old. N.E. Zaretskaya et al., "Radiocarbon chronology of the Shigir and Gorbunovo archaeological bog sites, Middle Urals, Russia", Proceedings of the 6th International Radiocarbon and Archaeology Symposium, (E Boaretto and N R Rebollo Franco eds.), RADIOCARBON Vol 54, No. 3–4, 2012, 783–794.

- ^ The term "Mesolithic" is not a useful term for the periodization of the South Asian Stone Age, as certain tribes in the interior of the Indian subcontinent retained a mesolithic culture into the modern period, and there is no consistent usage of the term. The range 12,000–4,000 BP is based on the combination of the ranges given by Agrawal et al. (1978) and by Sen (1999), and overlaps with the early Neolithic at Mehrgarh. D.P. Agrawal et al., "Chronology of Indian prehistory from the Mesolithic period to the Iron Age", Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 7, Issue 1, January 1978, 37–44: "A total time bracket of c. 6,000–2,000 B.C. will cover the dated Mesolithic sites, e.g. Langhnaj, Bagor, Bhimbetka, Adamgarh, Lekhahia, etc." (p. 38). S.N. Sen, Ancient Indian History and Civilization, 1999: "The Mesolithic period roughly ranges between 10,000 and 6,000 B.C." (p. 23).

External links

Media related to Mesolithic at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mesolithic at Wikimedia Commons

![Animated image showing the sequence of engravings on a pendant excavated from the Mesolithic archaeological site of Star Carr in 2015[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/Star_Carr_Engraved_Pendant.gif/142px-Star_Carr_Engraved_Pendant.gif)