Daytona International Speedway

| |

| |

| Location | 1801 West International Speedway Blvd, Daytona Beach, Florida 32114 |

|---|---|

| Time zone | UTC−5 (UTC−4 DST) |

| Coordinates | 29°11′8″N 81°4′10″W / 29.18556°N 81.06944°W |

| Capacity | 101,500–167,785 (w/ infield, depending on configuration) 123,500 (grandstand capacity) |

| Owner | NASCAR (2019–present) International Speedway Corporation (1959–2019)[1] |

| Operator | NASCAR (1959–present) |

| Broke ground | November 25, 1957 |

| Opened | February 22, 1959 |

| Construction cost | US$3 million |

| Architect | Charles Moneypenny William France, Sr. |

| Major events | Current:

Former:

|

| Website | http://www.daytonainternationalspeedway.com/ |

| NASCAR Tri-Oval (1959–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.500 miles (4.023 km) |

| Turns | 4 |

| Banking | Turns: 31° Tri-oval: 18° Back straightaway: 3° |

| Race lap record | 0:43.682 ( |

| Sports Car Course (1985–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.560 miles (5.729 km) |

| Turns | 12 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 31° Tri-Oval: 18° Back straightaway: 2° Infield: 0° (flat) |

| Race lap record | 1:33.724 ( |

| NASCAR Road Course (2020–2021) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.570 miles (5.745 km) |

| Turns | 14 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 31° Tri-Oval: 18° Back straightaway: 2° Infield: 0° (flat) |

| Race lap record | 1:55.677 ( |

| Motorcycle Course (2005–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.950 miles (4.748 km) |

| Turns | 12 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 31° Tri-Oval: 18° Back straightaway: 2° Infield: 0° (flat) |

| Sports Car Course (1984)[2] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.869 miles (6.228 km) |

| Race lap record | 1:45.209 ( |

| Sports Car Course (1975–1983)[2] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.840 miles (6.180 km) |

| Race lap record | 1:45.360 ( |

| Sports Car Course (1959–1974)[2] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.810 miles (6.132 km) |

| Turns | 7 |

| Race lap record | 1:41.250 ( |

| Dirt Flat Track | |

| Surface | Dirt |

| Length | 0.25 miles (0.40 km) |

| Turns | 4 |

| Banking | Flat |

| Short Oval | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 0.40 miles (0.64 km) |

| Turns | 4 |

| Banking | Flat |

| Race lap record | 0:20.129 (Nate Monteith, Monteith Racing, 2013, Whelen All-American Series) |

Daytona International Speedway is a race track in Daytona Beach, Florida, United States, about 50 mi (80 km) north of Orlando. Since opening in 1959, it has been the home of the Daytona 500, the most prestigious race in NASCAR as well as its season opening event. The venue also hosts the 24 Hours of Daytona, one of three IMSA races that make up the Triple Crown of endurance racing. In addition to NASCAR and IMSA, the track also hosts races of ARCA, AMA Superbike, SCCA, and AMA Supercross. The track features multiple layouts including the primary 2.500 mi (4.023 km) high-speed tri-oval, a 3.560 mi (5.729 km) sports car course, a 2.950 mi (4.748 km) motorcycle course, and a 1,320 ft (400 m) karting and motorcycle flat-track. The track's 180-acre (73 ha) infield includes the 29-acre (12 ha) Lake Lloyd, which has hosted powerboat racing.

The track was built in 1959 by NASCAR founder William "Bill" France Sr. to host racing that was held at the former Daytona Beach Road Course. His banked design permitted higher speeds and gave fans a better view of the cars. The speedway is operated by NASCAR pursuant to a lease with the City of Daytona Beach on the property that runs until 2054.[1][3] The venue describes itself as the "World Center of Racing".[4]

Lights were installed around the track in 1998, and today it is the third-largest single-lit outdoor sports facility. The speedway has been renovated four times, with the infield renovated in 2004 and the track repaved in 1978 and 2010. On January 22, 2013, the fourth speedway renovation was unveiled. On July 5, 2013, ground was broken on "Daytona Rising" to remove backstretch seating and completely redevelop the frontstretch seating. The renovation was by design-builder Barton Malow Company in partnership with Rossetti Architects. The project was completed in January 2016, and cost US $400 million. It emphasized improved fan experience with five expanded and redesigned fan entrances (called "injectors"), as well as wider and more comfortable seats, and more restrooms and concession stands. After the renovations were complete, the track's grandstands had 101,500[5] permanent seats with the ability to increase permanent seating to 125,000.[6][7] The project was finished before the start of Speedweeks in 2016.

Track history

[edit]Construction

[edit]NASCAR founder William France Sr. began planning for the track in 1953 as a way to promote the series, which at the time was racing on the Daytona Beach Road Course.[8] France met with Daytona Beach engineer Charles Moneypenny to discuss his plans for the speedway. He wanted the track to have the highest banking possible to allow the cars to reach high speeds and to give fans a better view of the cars on track. Moneypenny traveled to Detroit, Michigan to visit the Ford Proving Grounds which had a high-speed test track with banked corners. Ford shared their engineering design of the track with Moneypenny, providing the needed details of how to transition the pavement from a flat straightaway to a banked corner. France took the plans to the Daytona Beach city commission, who supported his idea and formed the Daytona Beach Speedway Authority.[9]

The city commission agreed to lease the 447-acre (180.9 ha) parcel of land adjacent to Daytona Beach Municipal Airport to France's corporation for $10,000 a year over a 50-year period. France then began working on building funding for the project and found support from a Texas oil millionaire, Clint Murchison, Sr. Murchison lent France $600,000 along with the construction equipment necessary to build the track. France also secured funding from Pepsi-Cola, General Motors designer Harley Earl, a second mortgage on his home and selling 300,000 stock shares to local residents. Ground broke on construction of the 2.500 mi (4.023 km) speedway on November 25, 1957.[9]

To build the high banking, crews had to excavate over a million square yards of soil from the track's infield.[10] Because of the high water table in the area, the excavated hole filled with water to form what is now known as Lake Lloyd, named after Joseph "Sax" Lloyd, one of the original six members of the Daytona Beach Speedway Authority. (The lake was stocked with 65,000 fish, and France arranged speedboat races on it.)[11] 22 tons of lime mortar had to be brought in to form the track's binding base, over which asphalt was laid. Because of the extreme degree of banking, Moneypenny had to come up with a way to pave the incline. He connected the paving equipment to bulldozers anchored at the top of the banking. This allowed the paving equipment to pave the banking without slipping or rolling down the incline. Moneypenny subsequently patented his construction method[citation needed] and later designed Talladega Superspeedway and Michigan International Speedway. By December 1958, France had begun to run out of money and relied on race ticket sales to complete construction.[9] He also received a substantial sum of money from the Pepsi company after attempting to obtain the money to finish construction from the Coca-Cola Company and being turned down. For years from when the track opened to France's death, France never allowed Coca-Cola to be sold as a concession at any of the tracks he owned as a result.

The first practice run on the new track was on February 6, 1959. On February 22, 1959, 42,000 people attended the inaugural Daytona 500.[9] Its finish was as startling as the track itself: Lee Petty beat Johnny Beauchamp in a photo finish that took three days to adjudicate.[12] When the track opened it was the fastest race track to host a stock car race, until Talladega Superspeedway opened 10 years later.[citation needed] On April 4, it hosted a 100 mi (160.9 km) Champ Car event which saw Jim Rathmann beat Dick Rathmann and Rodger Ward, at an average speed of 170.26 mph (274.01 km/h), at the time the fastest motor race ever.[12] It was the occasion of Daytona's first fatality: George Amick, attempting to overtake for third late in the race, hit a wall and was killed.[12] April 5, a scheduled 1,000 km (620 mi) sports car event (shortened to 560 mi (900 km) by darkness) was won by Roberto Mieres and Fritz d'Orey, who shared a Porsche RSK, which proved more durable than more potent competition.[12]

Lights were installed around the track in 1998 to run NASCAR's July race, the Coke Zero 400 at night. The track was the world's largest single lighted outdoor sports facility until being surpassed by Losail International Circuit in 2008.[citation needed] Musco Lighting installed the lighting system, which took into account glare and visibility for aircraft arriving and departing nearby Daytona Beach International Airport, and costs about $240 per hour when in operation.[13]

Layouts

[edit]Tri-oval

[edit]

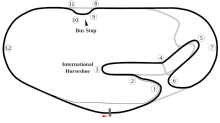

Daytona's tri-oval is 2.500 mi (4.023 km) long with 31° banking in the turns and 18° banking at the start/finish line. The front straight is 3,800 ft (1,200 m) long and the back straight (or "superstretch") is 3,000 ft (910 m) long. The tri-oval shape was revolutionary at the time as it greatly improved sight lines for fans. It is one of the three tracks on the NASCAR Cup Series circuit that are considered "drafting tracks", the others being Talladega Superspeedway and Atlanta Motor Speedway.[14]

On July 15, 2010, repaving of the track began. This came almost a year earlier than planned due to the track coming apart during the 2010 Daytona 500. The project used an estimated 50,000 tons[vague] of asphalt to repave 1.4 million square feet (130,000 m2) including the racing surface, apron, skid pads and pit road. Because of good weather, the project was completed ahead of schedule.[15]

On October 9, 2013, Colin Braun drove a Daytona Prototype car prepared by Michael Shank Racing to set a single-lap record on the tri-oval configuration of 222.971 mph (358.837 km/h).[16] During NASCAR events, it takes less than a minute for the cars to complete a lap around the 2.500 mi (4.023 km) tri-oval course.

Road courses

[edit]

While the more famous 24 Hours of Le Mans is held near the summer solstice, Daytona's endurance race is held in winter (meaning more of the race is run at night). The track's lighting system is limited to 20% of its maximum output for the race to keep cars dependent on their headlights.[17]

The 3.810 mi (6.132 km) road course was built in 1959 and first hosted a three-hour sports car race called the Daytona Continental in 1962.[18] The race length became 2,000 km (1,200 mi) in 1964,[12] and in 1966 was extended to a 24-hour endurance race known as the Rolex 24 at Daytona. It was shortened again to six hours in 1972 and the 1974 rendition of the race was cancelled entirely.[12]

In 1973, a very sharp chicane was added at the end of the backstretch, approaching oval turn three.

In 1984[19] and 1985,[20] the layout was modified, re-profiling road course turns 1 and 2, and moving what is now turn 3 (nicknamed the "International Horseshoe") closer to its preceding turns. Also, the chicane on the backstretch was modified. A new entry leg was constructed approximately 400 ft (120 m) earlier, resulting in a longer, three-legged, "bus stop" shape. Cars would now enter in the first leg, bypass the second leg, and exit out of the existing third leg. Passing would now be possible inside the longer chicane. The construction resulted in a final length of 3.560 mi (5.729 km) for the complete road course.

In 2003, the backstretch chicane was modified once again. The middle leg was repaved and widened, and now cars would enter through the first leg, and exit out of the second leg. The existing third leg was abandoned. This allowed cars a cleaner entry into oval turn three. After favorable results, in 2010 the third leg was demolished and removed permanently.

In 2005, a second infield road course configuration was constructed, primarily for motorcycles. Due to fears of tire wear on the banked oval sections, oval turns 1 and 2 were bypassed giving the new course a length of 2.950 mi (4.748 km). The Daytona SportBike that runs the Daytona 200 however, uses the main road course except for the motorcycle Pedro Rodríguez Hairpin (tighter than the one used for cars; the car version is used as an acceleration lane for motorcycles).[21]

On September 26 and 27, 2006, the IndyCar Series held a compatibility test on the 10-turn, 2.73 mi (4.39 km) modified road course, and the 12-turn 2.950 mi (4.748 km) motorcycle road course with 5 drivers. The drivers who tested at the track were Vítor Meira, Sam Hornish Jr., Tony Kanaan, Scott Dixon and Dan Wheldon. This marked the first time since 1984 that open wheel cars have taken to the track at Daytona.[22] On January 31 – February 1, 2007, IndyCar returned for a full test involving 17 cars.[23]

On July 8, 2020, NASCAR announced that it would race the Daytona road course in all of its national series for the first time in mid-August (with the Cup Series racing the Go Bowling 235), due to current COVID-19 pandemic health restrictions in New York state (requiring 14 days self-isolation on arrival from other states) preventing the use of Watkins Glen International.[24] On July 30, a modification of the course to add a chicane near the exit of Turn 12 (Oval Turn Four) was announced, lengthening the course to 3.570 mi (5.745 km).[25]

On January 21, 2024, Pipo Derani set the fastest ever recorded lap of the modern Daytona road course, with a 1:32.656 driving a Cadillac V-Series.R during qualifying for the 2024 24 Hours of Daytona. During the same session, every entrant in the IMSA GTP class broke the course lap record previously set by Oliver Jarvis in a Mazda RT24-P in 2019. [26]

Supercross

[edit]During Daytona Beach Bike Week, a supercross track is built between the pit road and the tri-oval section of the track. Historically the track has used more sand than dirt, providing unique challenges to riders.[citation needed] The 2008–2013 track configurations were designed by former champion, Ricky Carmichael.[27]

Daytona has hosted an AMA Supercross Championship round uninterruptedly since 1971.[28]

Flat track and infield kart track

[edit]Popular dirt-track races in karting and flat-track motorcycle racing had been held at Daytona Beach Municipal Stadium but in 2009, the city announced the stadium was replacing its entire surface with FieldTurf, and thereby eliminating the flat-track racing at the stadium. To continue racing, speedway officials built the Daytona Flat Track, a new quarter-mile dirt track outside of turns 1 & 2 of the main superspeedway. It seats 5,000 in temporary grandstands and opened in December 2009 for WKA KartWeek. From 2010 to 2016, it also hosted the AMA Grand National Championship, before it was moved in 2017 to the tri-oval section and became a TT course.[29]

There is also a short paved kart/autocross track in the infield just inside of turn 3. The SCCA holds autocross on this track in addition to hosting sprint karting races during KartWeek.

Paved short track

[edit]In February 2012, it was announced that a 0.400 mi (0.644 km) paved short track would be constructed along the backstretch of the Speedway's main course, for NASCAR's lower-tier series to compete at during Speedweeks called the UNOH Battle at the Beach, which is similar to the Toyota All-Star Showdown, formerly held at Irwindale Speedway.[30] The first races were held on that track in February 2013. The track was shortened to a 0.375 mi (0.604 km) oval in 2014 by shorter straightaways. The future of racing at the short track became uncertain after 2015 with the grandstands on the back straightaway being demolished as a part of the Daytona Rising project.[31]

Football

[edit]In the fall of 1959, the track hosted several high school football games for the Father Lopez Green Wave in the first year of the school's football program.

The track hosted four college football games featuring the Daytona-based Bethune–Cookman Wildcats in 1974 and 1975. In early 2014 track president Joie Chitwood expressed a desire to bring football back to the track.[32]

Soccer

[edit]On July 2 and 3, 2022, the track hosted Daytona Soccer Fest, a 2 day event highlighted by a friendly match between heated Colombian rivals América de Cali and Deportivo Cali and a NWSL regular season match between the Orlando Pride and Racing Louisville FC.

Video games

[edit]In 1994, Sega released an arcade game called Daytona USA, using their Model 2 Arcade hardware. It was developed by their famed "AM2" development team. It featured a fully detailed 3D model of the circuit for the very first time. The soundtrack for the game included vocals by Takenobu Mitsuyoshi. It is widely considered to be one of the most successful and influential racing games of all time. Daytona USA spawned many sequels, both in the arcades and on various home video game consoles. The latest version, Daytona Championship USA, was released to arcades in 2017.[33]

iRacing.com have laser-scanned the facility twice. The first in 2008, and 2011 once the repave was completed. Both are available in official racing series. There has been no word to when and if it will be re-scanned now that the Daytona Rising project has now been completed.[34]

Both the oval layout and Rolex 24 Hour layout are available in both PlayStation 3 video games Gran Turismo 5 and Gran Turismo 6, and in the PlayStation 4 and PlayStation 5 game Gran Turismo 7. Daytona International Speedway is also featured in Forza Motorsport 6 and Forza Motorsport 7 for the Xbox One and Windows 10. The circuit returned to the Forza series in Forza Motorsport (2023) for Xbox Series X/S and Windows.

Real Racing 3's second NASCAR update featured the Daytona International Speedway as a new circuit coming in three layouts. In addition to the oval and Rolex 24 Hour layouts in Gran Turismo, there also exists a Daytona 200 layout in the game.

Fatalities

[edit]Forty-one people have been fatally injured in on-track incidents: 24 car drivers, twelve motorcyclists, three go-kart drivers, one powerboat racer, and one track worker. The most notorious death was that of Dale Earnhardt, who was killed on the final lap of the 2001 Daytona 500 on February 18, 2001.[35] Earnhardt is still Daytona International Speedway's most successful driver, with a total of 34 career victories (12 Daytona 500 qualifying races, 7 NASCAR Xfinity Series races, 6 Busch Clash races, 6 IROC races, 2 Pepsi 400 July Races and the 1998 Daytona 500).

Fan amenities

[edit]

Hard Rock Bet Fanzone

[edit]The Hard Rock Bet Fanzone is an access package similar to pit passes for fans to get closer to drivers and race teams. The fanzone was built in 2004 as part of a renovation of the track's infield.[36] Fans are able to walk on top of the garages, known as the "fandeck", and view track and garage activity. Fans can also view race teams working in the garage, including NASCAR technical inspection, through windows. The garage windows also include slots for fans to hand merchandise to drivers for autographs. The fanzone also includes a live entertainment stage, additional food and drink areas and various other activities and displays.[37]

The 2004 renovation of the infield, headed by design firm HNTB,[38] was the first major renovation of the infield in the history of the track.[39] In addition to the fanzone, a new vehicle and pedestrian tunnel was built under turn 1. The tunnel posed a challenge to engineers because it was to be built under the water table. Another challenge came during construction when three named hurricanes passed by the track, flooding much of the excavation work. The infield renovation involved landscaping and hardscaping, such as a new walkway along the shore of Lake Lloyd, and the construction of 34 new buildings, including garages and fueling stations, offices and inspection facilities, and a club. The renovation project received a 2005 Award for Excellence from Design-Build Institute of America.[39] Following the success of the UNOH Fanzone at Daytona, Las Vegas Motor Speedway and Kansas Speedway each built a similar infield fanzone.[citation needed] On December 9, 2016, the speedway announced that the University of Northwestern Ohio purchased entitlement rights to the fanzone, and that the area will be named 'UNOH Fanzone'.[40] On January 25, 2024, it announced the naming rights had been purchased by Hard Rock Cafe and named 'Hard Rock Bet Fanzone' after their sports betting service.[41]

Budweiser Party Porch

[edit]The Budweiser Party Porch was a 46-foot-high (14.0 m) porch located along the backstretch of the track. It was built on top of a portion of the backstretch grandstands and includes a 277-foot-wide (84.4 m), 33-foot-tall (10.1 m) sign, the largest sign in motorsports.[42] The porch featured tables, food and drinks, offering fans a "fun-filled" atmosphere that breaks fans away from the confines of grandstand seating without sacrificing the view. Below the porch was an interactive fan zone featuring amusement rides, a go-kart track, show cars and merchandise trailers.[43] After the 2015 racing season, the Party Porch was torn down with the backstretch grandstands as part of the DAYTONA Rising project.

Layout configurations

[edit]Events

[edit]Current

[edit]2.5-mile superspeedway

[edit]

- NASCAR Cup Series[44][45]

- Points-paying races: Daytona 500, Coke Zero Sugar 400

- Qualifying races: Bluegreen Vacations Duel

- NASCAR Xfinity Series[44][45]

- NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series[44]

- ARCA Menards Series

Road course

[edit]- IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship (formerly Grand-American Rolex Sports Car Series)[46]

- Michelin Pilot Challenge

- BMW M Endurance Challenge

- WKA Vega Road Racing Series driven by Mazda

- Daytona Kart Week

- ChampCar Endurance Series

- The 14-Hours of Daytona Beach

- WRL

- Concorso Daytona 14 Hours

- MotoAmerica

Other

[edit]- Monster Energy AMA Supercross

- Daytona Supercross by Honda[47]

- Ricky Carmichael Amateur Supercross

- AMA Pro Flat Track Racing

- Daytona Flat Track

- WKA Mazda/Bridgestone Manufacturers Cup Series

- Daytona Kart Week

- WKA Speedway Dirt

- Daytona Dirt World Championships

- Daytona Beach Half Marathon

- Welcome to Rockville

Former

[edit]- AMA Pro Daytona Sportbike Championship

- Daytona 200 (2009–2014)[45]

- ARCA Menards Series

- General Tire 100 (2020)

- Grand American (1968–1972)

- Grand Prix motorcycle racing

- United States motorcycle Grand Prix (1961–1965)

- IMSA GT Championship

- Daytona Finale (1972–1986, 1996)

- Paul Revere 250 (1973–1983)

- Rolex 24 at Daytona (1975–1997)

- IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship

- WeatherTech 240 (2020)

- International Race of Champions (1974–1978, 1985–1989, 1991–2006)

- ISCARS Dash Touring Series

- IPOWER Dash 150 (1979–2004)

- DaytonaUSA.com 150 (2001)[48]

- LATAM Challenge Series (2014)

- NASCAR Camping World Truck Series

- BrakeBest Select 159 (2020–2021)

- NASCAR Convertible Division

- 100 Mile Qualifying Races (1959)

- NASCAR Cup Series

- Busch Clash (1979–2021)

- O'Reilly Auto Parts 253 (2020–2021)

- NASCAR K&N Pro Series East (1988–1992, 1995–1997, 2014)

- NASCAR Xfinity Series

- Super Start Batteries 188 (2020–2021)

- Rolex Sports Car Series

- Brumos Porsche 250 (2000, 2002–2010)

- Daytona Finale (2001–2003)

- Rolex 24 at Daytona (2000–2013)

- SCCA National Championship Runoffs (1965, 1967, 1969, 2015)

- Trans-Am Series

- Trans-Am Finale (1967–1968, 1984, 2013–2019)

- United States Road Racing Championship

- Rolex 24 at Daytona (1998–1999)

- USAC Championship Car

- USAC Daytona 100 (1959)

- World Sportscar Championship

- 24 Hours of Daytona (1962–1973, 1975, 1977–1981)

Track records

[edit]As of August 2024, track records on the 2.500 mi (4.023 km) tri-oval are followed as:[49]

| Record | Year | Date | Driver | Car Make | Time | Speed/Avg Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NASCAR Cup Series | ||||||

| Qualifying (Old Gen) | 1987 | February 9 | Bill Elliott | Ford | 42.783 | 210.364 mph (338.548 km/h) |

| Qualifying (Next Gen) | 2024 | August 23 | Micheal McDowell | Ford | 49.136 |

183.165 mph (294.775 km/h) |

| Race (500 miles - 1 Lap) | 2020 | February 17 | Erik Jones | Toyota | 43.682[50] | 206.034 mph (331.580 km/h) |

| Race (400 miles) | 1980 | July 4 | Bobby Allison | Mercury | 2:18:21 | 173.473 mph (279.178 km/h) |

| Race (250 miles) | 1961 | July 4 | David Pearson | Pontiac | 1:37:13 | 154.294 mph (248.312 km/h) |

| NASCAR Xfinity Series | ||||||

| Qualifying | 1987 | Tommy Houston | Buick | 46.298 | 194.389 mph (312.839 km/h) | |

| Race (300 miles - 1 Lap) | 2019 | February 16 | Jeffrey Earnhardt | Toyota | 45.554[51] | 197.568 mph (317.955 km/h) |

| Race (250 miles) | 2003 | July 4 | Dale Earnhardt Jr. | Chevrolet | 1:37:35 | 153.715 mph (247.380 km/h) |

| NASCAR Truck Series | ||||||

| Qualifying | 2015 | February 20 | Spencer Gallagher | Chevrolet | 47.332 | 190.146 mph (306.010 km/h) |

| Race (250 miles - 1 Lap) | 2019 | February 15 | David Gilliland | Toyota | 46.008[52] | 195.618 mph (314.817 km/h) |

| IROC | ||||||

| Race (100 miles) | 1996 | February 16 | Dale Earnhardt | Pontiac | 47.926 | 187.793 mph (302.224 km/h) |

| ARCA Menards Series | ||||||

| Qualifying | 1987 | February 8 | Bill Venturini | Chevrolet | 44.954 | 200.209 mph (322.205 km/h) |

| Race (200 miles) | 1998 | February 8 | Kenny Irwin Jr. | Ford | 1:18:20 | 153.191 mph (246.537 km/h) |

| ARCA Menards Series East | ||||||

| Qualifying | 1989 | February 18 | Kenny Wallace | Pontiac | 46.810 | 192.271 mph (309.430 km/h) |

| Race (300 miles) | 1995 | February 18 | Chad Little | Ford | 1:59:25 | 150.732 mph (242.580 km/h) |

| USAC IndyCar | ||||||

| Qualifying | 1959 | April 4 | Dick Rathman | Kurtis | 51.970 | 173.21 mph (278.75 km/h) |

| Race (100 miles) | 1959 | April 4 | Jim Rathmann | Watson | 52.861 | 170.261 mph (274.009 km/h) |

Race lap records

[edit]As of March 2024, the fastest official race lap records at the Daytona International Speedway are listed as:

Weather and climate

[edit]Daytona has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), which enables year-round use of the facility. Light frosts are in theory possible, but unlikely, during the 24-hour event's nighttime under clear conditions, but general racing conditions are mild also during winter. With a dry season taking place during the winter months, the 500 generally has good odds of being run without rain delays. The summer event under the floodlights is more likely to undergo disturbances, due to the rainy tendencies of the hot, muggy, and humid summers. Due to the complete difference of seasons, the two NASCAR Cup races at Daytona see vastly different track conditions.

| Climate data for Daytona Beach Int'l, Florida (1981–2010 normals,[98] extremes 1923–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 92 (33) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

90 (32) |

88 (31) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 81.7 (27.6) |

83.4 (28.6) |

86.8 (30.4) |

89.5 (31.9) |

93.6 (34.2) |

95.1 (35.1) |

96.1 (35.6) |

95.4 (35.2) |

92.4 (33.6) |

89.5 (31.9) |

85.1 (29.5) |

82.5 (28.1) |

97.5 (36.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 68.4 (20.2) |

70.7 (21.5) |

74.5 (23.6) |

79.2 (26.2) |

84.7 (29.3) |

88.4 (31.3) |

90.2 (32.3) |

89.6 (32.0) |

86.9 (30.5) |

82.0 (27.8) |

76.0 (24.4) |

70.4 (21.3) |

80.1 (26.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 47.3 (8.5) |

50.1 (10.1) |

54.2 (12.3) |

58.6 (14.8) |

65.4 (18.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

73.0 (22.8) |

73.4 (23.0) |

72.2 (22.3) |

65.9 (18.8) |

57.3 (14.1) |

50.5 (10.3) |

61.7 (16.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 29.6 (−1.3) |

33.3 (0.7) |

38.4 (3.6) |

44.6 (7.0) |

54.8 (12.7) |

65.2 (18.4) |

68.4 (20.2) |

69.5 (20.8) |

65.2 (18.4) |

51.1 (10.6) |

41.7 (5.4) |

32.8 (0.4) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 15 (−9) |

24 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

40 (4) |

52 (11) |

60 (16) |

63 (17) |

52 (11) |

39 (4) |

25 (−4) |

19 (−7) |

15 (−9) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 2.74 (70) |

2.78 (71) |

4.24 (108) |

2.18 (55) |

3.13 (80) |

5.83 (148) |

5.83 (148) |

6.40 (163) |

6.96 (177) |

4.21 (107) |

2.69 (68) |

2.63 (67) |

49.62 (1,260) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.5 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 14.0 | 13.5 | 10.6 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 115.0 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 64 | 73 | 75 | 69 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 69 | 67 | 64 | 64 | 70 | 67 |

| Source 1: NOAA[99][100] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (sunshine data)[101] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

[edit]-

Main Entrance at night (prior to renovation)

-

Cars practicing in 2004

-

Old Flagstand

-

Grandstand (prior to renovation)

-

Paul Revere 250 restart after a caution

-

View from the former backstretch grandstands at night

-

Endurance kart race

-

Racetrack skidmarks and view of old grandstand

-

View of Lake Lloyd

-

Infield garages

-

Infield view from President's Row

-

View of Victory Lane from a skybox

-

Statue of Dale Earnhardt Sr. holding his winner's trophy

-

Rolex Clock at the garage

-

Aerial view

See also

[edit]- 944 Cup

- List of Daytona International Speedway fatalities

- Daytona 500 Experience

- Motorsports Hall of Fame of America

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Long, Mark (May 22, 2019). "NASCAR buys International Speedway Corp. for $2B". Associated Press. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Daytona - RacingCircuits.info". RacingCircuits.info. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ Lane, Mark (August 5, 2018). "Little-known special district leases land under the Daytona International Speedway". Times Herald-Record. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Mike Hembree (February 5, 2018). "How Daytona Beach Became the 'World Center of Racing'". Autoweek.

- ^ "DAYTONA Rising". www.daytonainternationalspeedway.com. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Reed, Steve (January 22, 2013). "Daytona International unveils plans for upgrade". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ "Daytona Rising". Daytona International Speedway. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ Hawkins, Jim (2003). "Big Bill's Dream for America's Speed Capital". Tales from the Daytona 500 (illustrated ed.). Sports Publishing LLC. pp. 13–14 of 200. ISBN 978-1-58261-530-1. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Aumann, Mark. "How Daytona International Speedway was created". Nascar.com.

- ^ "World Marks Likely at New Daytona Track". The Indianapolis Star. January 4, 1959. p. 21. Retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kettlewell, Mike. "Daytona", in Northey, Tom, ed. World of Automobiles (London: Orbis, 1974), Volume 5, p.503.

- ^ a b c d e f Kettlewell, p.503.

- ^ "Daytona International Speedway". Musco Lighting. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "Track Facts". Daytonainternationalspeedway.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "Goodyear Tire Test on Daytona's New Racing Surface Set For Dec. 15–16". Daytona International Speedway. November 20, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "Braun Sets Daytona Speed Record". Motor Racing Network. Concord, North Carolina. October 9, 2013. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ "Race Profile – 24 Hours of Daytona". Sports Car Digest. January 23, 2009. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "Daytona International Speedway". na-motorsports.com. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ "World Sports Racing Prototypes - IMSA 1984". wsrp.ic.cz. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007.

- ^ "World Sports Racing Prototypes - IMSA 1985". wsrp.ic.cz. Archived from the original on April 8, 2009.

- ^ Adams, Dean (August 12, 2004). "Daytona Changes Course". Superbikeplanet.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "IRL Begins Testing at Daytona Road Course". Daytona International Speedway. September 26, 2006. Archived from the original on December 28, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "IndyCar Series Kicks Off Two-Day Test at Daytona". Daytona International Speedway. January 31, 2007. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "NASCAR reveals rest of 2020 regular-season schedule". NASCAR.com. July 8, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "Daytona Road Course to have chicane; plus race lengths". Official Site Of NASCAR. July 30, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Every IMSA GTP Car Beats Old Daytona Lap Record as Cadillac Nabs Rolex 24 Pole". The Drive. January 22, 2024. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Ricky Carmichael Designs Daytona Supercross By Honda Course For Second Straight Year". Daytona International Speedway. January 30, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "2015 AMA Supercross media guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ "AMA Flat Track: DIS to Construct Dirt Track". Speed. July 31, 2009. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ Haddock, Tim (February 15, 2012). "Source: Daytona building short track". ESPN. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ "$400 million Daytona International Speedway renovation nearing completion". July 3, 2015.

- ^ Newcomb, Tim (January 21, 2012). "Source: Daytona International Speedway hopes to host college football game after renovation". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Daytona Championship USA Officially Released to Arcades". June 16, 2017.

- ^ "IRacing Tracks Archive".

- ^ "Auto racing fatalities list". USA Today. February 18, 2001. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012.

- ^ Hembree, Mike (July 28, 2009). "NASCAR fans get in the 'zone' at Daytona International Speedway". Scene. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "Sprint FANZONE". Daytona international Speedway. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "Daytona Speedway". HNTB. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Engdahl, David. "Daytona International Speedway Renovation". American Institute of Architects. Retrieved November 22, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "UNOH to Serve as Entitlement Partner of Fanzone". daytonainternationalspeedway.com. Daytona International Speedway. December 9, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ Daytona International Speedway [@DAYTONA] (January 24, 2024). "The fanzone has a new look! We are thrilled to announce that the infield fanzone will be named the @HardRockBet Fanzone 🤩" (Tweet). Retrieved January 25, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Budweiser Signs Multi-Year Renewal with Daytona". May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Budweiser Party Porch Is The Place To Be on the Superstretch for the 52nd Annual Daytona 500". The Catchfence. February 9, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Daytona International Speedway – travel – ESPN". ESPN. January 14, 2011. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Events Calendar". Daytona International Speedway. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "2011 Rolex Series". Grand-am.com. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "Daytona Supercross by Honda". Daytona International Speedway. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "2001 DaytonaUSA.com 150 – 51's Third Turn". thethirdturn.com. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ "Race Results at Daytona International Speedway". racing-reference.info. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "2020 NASCAR Cup Series Daytona 500". February 17, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "NASCAR Xfinity 2019 - Daytona - Race Fastest Laps". February 16, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "2019 NASCAR Truck Series NextEra Energy 250". February 15, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "Daytona - Motor Sport Magazine". Motor Sport Magazine. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "2024 ARCA Hard Rock Bet 200". February 17, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c "2022 Rolex 24 At Daytona - Race Official Results (24 Hours)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). February 10, 2022. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "2024 Rolex 24 At Daytona - Race Official Results (24 Hours)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Daytona 24 Hours 1992". February 2, 1992. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1990". February 4, 1990. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ "2014 Daytona 24 Hours". January 26, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1998". February 1, 1998. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 2002". February 3, 2002. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ a b "2020 Rolex 24 At Daytona - Race Official Results (24 Hours)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). January 31, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "2017 Rolex 24 At Daytona - Race Official Results by Class" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). February 1, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "Trans Am Championship Presented by Pirelli - Round 12: November 13–16 2019 - Daytona International Speedway - TA SGT GT Round 11 (Official Race Results)" (PDF). November 16, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 2000". February 6, 2000. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 2013". January 27, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "2022 Ferrari Challenge North America - Trofeo Pirelli - Daytona - Race 2 Official Results (30 Minutes)" (PDF). April 11, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "2024 MotoAmerica Daytona 200 Supersport Race Result" (PDF). March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1993". January 31, 1993. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 250 Miles Paul Revere 2002". July 6, 2002. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ "Trans Am Championship Presented by Pirelli - Round 12: November 13–16 2019 - Daytona International Speedway - TA2 Round 13 Powered by AEM Infinity - Official Race Results Revised" (PDF). November 16, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1999". January 31, 1999. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "Daytona Finale 3 Hours 1985". December 1, 1985. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 2003". February 2, 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "2023 Rolex 24 at Daytona - IMSA Michelin Pilot Challenge - Race Official Results (4 Hours)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). January 31, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 2001". February 4, 2001. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ "2024 Daytona 200 Twins Cup Race 2" (PDF). March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ "2024 BMW M Endurance Challenge at Daytona - Race Official Results (4 Hours)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). February 14, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1995". February 5, 1995. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1994". February 6, 1994. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "2023 Rolex 24 at Daytona - Idemitsu Mazda MX-5 Cup Presented by BFGoodrich - Race 2 Official Results (45 Minutes)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). January 31, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "2021 NASCAR Cup Series O´Reilly Auto Parts 253". February 21, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ "2021 NASCAR Xfinity Series Super Start Batteries 188". February 20, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ "2021 NASCAR Truck Series Brakebest Brake Pads 159". February 19, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Daytona Finale 3 Hours 1984". November 25, 1984. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona Finale 3 Hours 1982". November 28, 1982. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ a b "Daytona Finale 250 Miles 1980". November 30, 1980. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "Summer Speed Week '83 Daytona". July 4, 1983. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ "Daytona Finale 250 Miles 1981". November 29, 1981. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ "Daytona '78". June 1, 1978. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ "Daytona 250 Miles Paul Revere 1978". July 4, 1978. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ "1971 Daytona 24 Hours". Motor Sport Magazine. January 30, 1971. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "A.M.A. Daytona Nationals". June 1, 1965. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1970". February 1, 1970. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1973". February 4, 1973. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 24 Hours 1969". February 2, 1969. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Daytona 2000 Kilometres 1964". February 16, 1964. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Station Name: FL DAYTONA BEACH INTL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Daytona Beach, Florida, USA – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

External links

[edit] Media related to Daytona International Speedway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Daytona International Speedway at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Daytona International Speedway race results at Racing-Reference

- Daytona Rising renovation site Archived December 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Speedway Page Archived May 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine on NASCAR.com

- Jayski's Daytona International Speedway Page

- Trackpedia guide to driving this track

- Satellite picture by Google Maps

- VisitingFan.com: Reviews of Daytona International Speedway

- Deaths at Daytona at Fox Sports' website

- Auto-racing Fatalities list at USA Today website

- Daytona Deaths Chart at Sports Illustrated's website

- World Sportscar Championship

- NASCAR races at Daytona International Speedway

- Sports venues completed in 1959

- Motorsport venues in Florida

- Motorsport in Daytona Beach, Florida

- Sports venues in Volusia County, Florida

- Tourist attractions in Daytona Beach, Florida

- NASCAR tracks

- ARCA Menards Series tracks

- International Race of Champions tracks

- Grand Prix motorcycle circuits

- IMSA GT Championship circuits

- Buildings and structures in Daytona Beach, Florida

- 1959 establishments in Florida