The Double Life of Veronique

| The Double Life of Veronique | |

|---|---|

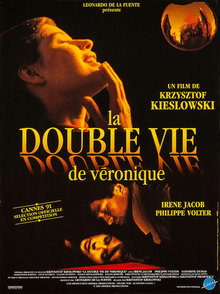

Theatrical release poster | |

| French | La double vie de Véronique |

| Directed by | Krzysztof Kieślowski |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Leonardo De La Fuente |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Sławomir Idziak |

| Edited by | Jacques Witta |

| Music by | Zbigniew Preisner |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Sidéral Films (France) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Box office | $2 million |

The Double Life of Veronique (French: La double vie de Véronique, Polish: Podwójne życie Weroniki) is a 1991 internationally co-produced drama film directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski, and starring Irène Jacob and Philippe Volter. Written by Kieślowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz, the film explores the themes of identity, love, and human intuition through the characters of Weronika, a Polish choir soprano, and her double, Véronique, a French music teacher. Despite not knowing each other, the two women share a mysterious and emotional bond that transcends language and geography.

The Double Life of Veronique was Kieślowski's first film produced partly outside his native Poland.[1] It won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury and the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, as well as the Best Actress award for Jacob.[2] Although selected as the Polish entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 64th Academy Awards, it was not accepted as a nominee.[3]

Plot

[edit]In 1968, a Polish girl glimpses the winter stars, while in France, another girl witnesses the first spring leaf. In 1990, a young Polish woman named Weronika is singing at an outdoor concert with her choir when a rainstorm interrupts their performance. Later that night, she has sex with her boyfriend, Antek, before leaving for Kraków the next day to be with her sick aunt. She tells her father that she has a strange feeling that she is not alone in the world. Once in Kraków, Weronika joins a local choir and successfully auditions. One day, while walking through the Main Square, she spots a French tourist who looks identical to her and watches as her doppelgänger boards a bus and takes photographs. During the choir's next concert, while singing a solo part, Weronika suffers a cardiac arrest and dies.

On the same day in Clermont-Ferrand, France, Véronique, who looks exactly like Weronika, is overcome with grief after having sex with her boyfriend and later tells her music teacher that she is quitting the choir. At school, Véronique attends a marionette performance with her class and then leads them in a musical piece by 18th-century composer Van den Budenmayer, who also wrote the music Weronika performed before her death. That night, Véronique sees the puppeteer at a traffic light motioning to her not to light the wrong end of her cigarette. Later, she hears a choir singing Van den Budenmayer's music on a mysterious phone call. Véronique visits her father and confesses to being in love with someone she does not know and feeling like she has lost someone from her life.

Back home, Véronique receives a package containing a shoelace. She discovers that the puppeteer's identity is Alexandre Fabbri, a children's book author. Véronique reads his books and then receives a new package from her father with a cassette tape containing sounds such as a typewriter, a train station and a fragment of music by Van den Budenmayer. The postage stamp on the envelope leads her to the Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris, where Alexandre is waiting for her in a café. He confesses to sending the packages to see if she would come to him. Enraged, Véronique leaves and checks into a nearby hotel. Alexandre follows her and apologises to her. They confess their feelings for each other and fall asleep together.

The next morning, Véronique tells Alexandre that throughout her life, she has felt like she is "in two places at the same time", and believes that someone has been guiding her life. She shows him the contents of her handbag, including a proof sheet of photos from her recent trip to Poland. Alexandre notices what he thinks is a photo of Véronique, but she assures him that it is not her. Overwhelmed, Véronique breaks down in tears, and Alexandre comforts her. It becomes clear that Weronika's fate has influenced Véronique's decision to stop singing and avoid a similar fate.

Later, Véronique visits Alexandre at his apartment and sees him working on a pair of marionettes that resemble her. Alexandre explains that he needs a backup in case the original puppet gets damaged. He demonstrates how to operate the puppet while the duplicate lies on the table. Alexandre reads her his new book about two women born on the same day in different cities who have a mysterious connection. Later that day, Véronique visits her father's house and touches an old tree trunk. Her father, who is inside the house, seems to sense her presence.

Cast

[edit]- Irène Jacob as Weronika and Véronique[Note 1]

- Halina Gryglaszewska as the aunt

- Kalina Jędrusik as the gaudy woman

- Aleksander Bardini as the orchestra conductor

- Władysław Kowalski as Weronika's father

- Jerzy Gudejko as Antek

- Jan Sterniński as the lawyer

- Philippe Volter as Alexandre Fabbri

- Sandrine Dumas as Catherine

- Louis Ducreux as the professor

- Claude Duneton as Véronique's father

- Lorraine Evanoff as Claude

- Guillaume de Tonquédec as Serge

- Gilles Gaston-Dreyfus as Jean-Pierre

- Alain Frérot as the postman

- Youssef Hamid as the railroader

- Thierry de Carbonnières as the teacher

- Chantal Neuwirth as the receptionist

- Nausicaa Rampony as Nicole

- Boguslawa Schubert as the woman in the hat

- Jacques Potin as the man in the gray coat

Production

[edit]Filming style

[edit]The film incorporates a strong metaphysical element, yet the supernatural aspect of the story remains unexplained. Similar to Three Colours: Blue, Preisner's musical score plays a significant role in the plot and is credited to the fictional Van den Budenmayer. The cinematography is highly stylized, utilizing color and camera filters to create an ethereal atmosphere. Sławomir Idziak, the cinematographer, had previously experimented with these techniques in an episode of Dekalog, while Kieślowski expanded on the use of color for a wider range of effects in his Three Colours trilogy. Kieślowski had previously explored the concept of different life paths for the same individual in his Polish film, Przypadek (Blind Chance). The central choice faced by Weronika/Véronique is based on a brief subplot in the ninth episode of Dekalog.

Filming locations

[edit]The film was shot at locations including Clermont-Ferrand, Kraków and Paris.[4]

Alternative ending

[edit]In November 2006, a Criterion Collection region 1 DVD was released in the United States and Canada, which includes an alternative ending that Kieślowski changed in the edit at the request of Harvey Weinstein of Miramax for the American release. Kieślowski added four brief shots to the end of the film, which show Véronique's father emerging from the house and Véronique running across the yard to embrace him. The final image of the father and daughter embracing is shot from inside the house through a window.

Music

[edit]Zbigniew Preisner composed the score; however, in the film, the music is attributed to a fictitious 18th-century Dutch composer named Van den Budenmayer, who was created by Preisner and Kieślowski for use in screenplays.

Music credited to this imaginary composer also appears in Kieślowski's Dekalog (1988) and Three Colours: Blue (1993). In the latter, a theme from Van den Budenmayer's musique funebres is quoted in the Song for the Unification of Europe, and the E minor soprano solo is foreshadowed in Weronika's final performance.[5]

Puppetry

[edit]The puppet acts were performed by American puppeteer and sculptor Bruce Schwartz. Unlike most puppeteers who usually hide their hands in gloves or use strings or sticks, Schwartz shows his hands while performing.

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The Double Life of Veronique received mostly positive reviews. In her review in Not Coming to a Theater Near You, Jenny Jediny wrote, "In many ways, The Double Life of Veronique is a small miracle of cinema; ... Kieslowski’s strong, if largely post-mortem reputation among the art house audience has elevated a film that makes little to no sense on paper, while its emotional tone strikes a singular—perhaps perfect—key."[6]

In his review in The Washington Post, Hal Hinson called the film "a mesmerizing poetic work composed in an eerie minor key." Noting that the effect on the viewer is subtle but very real, Hinson concluded, "The film takes us completely into its world, and in doing so, it leaves us with the impression that our own world, once we return to it, is far richer and portentous than we had imagined." Hinson was particularly impressed with Jacob's performance:

This is an actress with an uncanny openness and vulnerability to the camera. She's beautiful, but in a completely unconventional way, and she has such changeable features that our interest is never exhausted. What's remarkable about her performance is how quiet it is; as an actress, she seems to work almost off the decibel scale. And yet she is remarkably alive on screen, remarkably present. She's a rare combination—a sexy yet soulful actress.[7]

In her review in The New York Times, Caryn James wrote, "Veronique is poetic in the truest sense, relying on images that can't be turned into prosaic statements without losing something of their essence. The film suggests mysterious connections of personality and emotion, but it was never meant to yield any neat, summary idea about the two women's lives."[8]

In his review in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert wrote, "The movie has a hypnotic effect. We are drawn into the character, not kept at arm's length with a plot." Ebert singled out Sławomir Idziak's innovative use of color and cinematography:

This is one of the most beautiful films I've seen. The cinematographer, Slawomir Idziak, finds a glow in Irene Jacob's pre-Raphaelite beauty. He uses a rich palette, including insistent reds and greens that don't "stand" for anything but have the effect of underlining the other colors. The other color, blending with both, is golden yellow, and then there are the skin tones. Jacob, who was 24 when the film was made, has a flawless complexion that the camera lingers near to. Her face is a template waiting for experience to be added.[9]

In 2009, Ebert added The Double Life of Veronique to his Great Movies list. Krzysztof Kieślowski's Dekalog and The Three Colours Trilogy are also on the list.[10]

In his review for Empire Online, David Parkinson called it "a film of great fragility and beauty, with the delicacy of the puppet theatre." He thought the film was "divinely photographed" by Slawomir Idziak, and praised Irène Jacob's performance as "simply sublime and thoroughly merited the Best Actress prize at Cannes." Parkinson saw the film as "compelling, challenging and irresistibly beautiful" and a "metaphysical masterpiece."[11]

At the All Movie web site, the film received a 4-star rating (out of 5) plus "High Artistic Quality" citation.[12] At About.com, which specializes in DVD reviews, the film received 5 stars (out of 5) in their critical review.[13] At BBC, the film received 3 stars (out of 5).[14] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian gave the film five stars out of five.[15] On the aggregate reviewer website Rotten Tomatoes, the film received an 84% positive rating from critics based on 31 reviews.[16]

Box office performance

[edit]The film was the 50th highest-grossing film of the year with a total of 592,241 admissions in France.[17] In North America the film opened on one screen grossing $8,572 its opening weekend. In total the film grossed $1,999,955 at the North American box office playing at a total of 22 theaters in its widest release which is a respectable result for a foreign art film.[18]

Home media

[edit]A digitally restored version of the film was released on DVD and Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection. The release includes audio commentary by Annette Insdorf, author of Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieślowski; three short documentary films by Kieślowski: Factory (1970), Hospital (1976), and Railway Station (1980); The Musicians (1958), a short film by Kieślowski's teacher Kazimierz Karabasz; Kieślowski’s Dialogue (1991), a documentary featuring a candid interview with Kieślowski and rare behind-the-scenes footage from the set of The Double Life of Véronique; 1966-1988: Kieślowski, Polish Filmmaker, a 2005 documentary tracing the filmmaker's work in Poland, from his days as a student through The Double Life of Veronique; a 2005 interview with actress Irène Jacob; and new video interviews with cinematographer Slawomir Idziak and composer Zbigniew Preisner. It also includes a booklet featuring essays by Jonathan Romney, Slavoj Zizek, and Peter Cowie, and a selection from Kieślowski on Kieślowski.[19]

Awards and nominations

[edit]- 1991 Cannes Film Festival Prize of the Ecumenical Jury (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1991 Cannes Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1991 Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actress (Irène Jacob) Won

- 1991 Cannes Film Festival nomination for the Golden Palm (Krzysztof Kieślowski)

- 1991 Los Angeles Film Critics Award for Best Music (Zbigniew Preisner) Won

- 1991 Warsaw International Film Festival Audience Award (Krzysztof Kieślowski) Won

- 1991 French Syndicate of Cinema Critics Award for Best Foreign Film Won[20]

- 1992 César Awards Nomination for Best Actress (Irène Jacob)

- 1992 César Awards nomination for Best Music Written for a Film (Zbigniew Preisner)

- 1992 Golden Globe Awards nomination for Best Foreign Language Film

- 1992 Guldbagge Awards nomination for Best Foreign Film[21]

- 1992 Independent Spirit Awards nomination for Best Foreign Film

- 1992 National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film Won[22]

In July 2021, the film was shown in the Cannes Classics section at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival.[23]

See also

[edit]- List of submissions to the 64th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Polish submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- Doppelgänger

Notes

[edit]- ^ Irène Jacob's voice was overdubbed by Anna Gornostaj for the Polish dialogue.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Double Life of Véronique". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ "La Double vie de Veronique". Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- ^ "Filming locations for The Double Life of Veronique". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Zbigniew Preisner". Musicolog. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Jediny, Jenny. "The Double Life of Véronique". Not Coming to a Theater Near You. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (13 December 1991). "The Double Life of Véronique". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ James, Caryn (2007). "The Double Life of Veronique (1991)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (25 February 2009). "The Double Life of Veronique (1991)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Great Movies". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Parkinson, David. "The Double Life of Veronique". Empire Online. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Reed, Anthony. "The Double Life of Veronique". Allmovie. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ "DVD Pick: The Double Life of Veronique". About.com. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Leyland, Matthew (12 March 2006). "The Double Life Of Veronique (La Double Vie De Véronique) (1991)". BBC. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (16 March 2006). "The Double Life of Véronique". The Guardian.

- ^ "La Double Vie de Véronique (The Double Life of Veronique) (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "La Double vie de Véronique". J.P.'s Box Office. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ "The Double Life of Veronique". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ "The Double Life of Véronique". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ "SFCC Critics' Award 1991". Syndicate de la Critique.

- ^ "La double vie de Véronique (1991)". The Swedish Film Database. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Awards for The Double Life of Veronique". Internet Movie Database. 12 February 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "2021 Cannes Classics Lineup Includes Orson Welles, Powell and Pressburger, Tilda Swinton & More". The Film Stage. 23 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Insdorf, Annette (1999). Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieślowski. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-6562-8.

- Kieślowski, Krzysztof (1998). Stok, Danusia (ed.). Kieślowski on Kieślowski. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-17328-4.

External links

[edit]- The Double Life of Veronique at IMDb

- The Double Life of Veronique at AllMovie

- The Double Life of Veronique at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Double Life of Veronique: The Forced Choice of Freedom – an essay by Slavoj ŽiŽek at The Criterion Collection

- The Double Life of Veronique: Through the Looking Glass – an essay by Jonathan Romney at The Criterion Collection

- 1991 films

- 1991 drama films

- 1991 fantasy films

- 1991 independent films

- 1990s fantasy drama films

- 1990s French films

- 1990s French-language films

- 1990s Polish-language films

- Canal+ films

- Films about classical music and musicians

- Films about singers

- Films directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski

- Films scored by Zbigniew Preisner

- Films set in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes

- Films set in Kraków

- Films set in Paris

- Films shot in Clermont-Ferrand

- Films shot in Kraków

- Films shot in Paris

- Films with screenplays by Krzysztof Kieślowski

- Films with screenplays by Krzysztof Piesiewicz

- French fantasy drama films

- French independent films

- Norwegian drama films

- Norwegian fantasy films

- Norwegian independent films

- Polish fantasy drama films

- Polish independent films

- StudioCanal films