Tetris

| Tetris | |

|---|---|

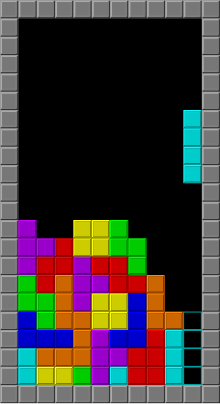

A typical Tetris game screen | |

| Designer(s) | Alexey Pajitnov |

| Platform(s) | List of Tetris variants |

| Release | IBM PC DOS |

| Genre(s) | |

| Mode(s) | |

Tetris (Russian: Тетрис[a]) is a puzzle video game created in 1985 by Alexey Pajitnov, a Soviet software engineer.[1] It has been published by several companies on more than 65 platforms, setting a Guinness world record for the most ported game. After a significant period of publication by Nintendo, in 1996 the rights reverted to Pajitnov, who co-founded the Tetris Company with Henk Rogers to manage licensing.

In Tetris, players complete lines by moving differently shaped pieces (tetrominoes), which descend onto the playing field. The completed lines disappear and grant the player points, and the player can proceed to fill the vacated spaces. The game ends when the uncleared lines reach the top of the playing field. The longer the player can delay this outcome, the higher their score will be. In multiplayer games, players must last longer than their opponents; in certain versions, players can inflict penalties on opponents by completing a significant number of lines. Some versions add variations such as 3D displays or systems for reserving pieces.

Tetris is often named one of the greatest video games. By December 2011, it had sold 202 million copies—approximately 70 million physical units and 132 million paid mobile game downloads—making it one of the best-selling video game franchises. The Game Boy version is one of the best-selling games of all time, with more than 35 million copies sold. Imagery from the game has influenced architecture, music, and cosplay. Tetris has also been the subject of various studies that have analyzed its theoretical complexity and have shown its effect on the human brain following a session, in particular the Tetris effect.

Gameplay

[edit]Tetris is primarily composed of a field of play in which pieces of different geometric forms, called "tetrominoes", descend from the top of the field.[2] During this descent, the player can move the pieces laterally and rotate them until they touch the bottom of the field or land on a piece that had been placed before it.[3] The player can neither slow down the falling pieces nor stop them, but can accelerate them, in most versions.[4]: 4 [5] The objective of the game is to use the pieces to create as many complete horizontal lines of blocks as possible. When a line is completed, it disappears, and the blocks placed above fall one rank.[3] Completing lines grants points, and accumulating a certain number of points or cleared lines moves the player up a level, which increases the number of points granted per completed line.[4]: 16

In most versions, the speed of the falling pieces increases with each level, leaving the player with less time to think about the placement.[3] The player can clear multiple lines at once, which can earn bonus points in some versions.[2] It is possible to complete up to four lines simultaneously with the use of the I-shaped tetromino; this move is called a "Tetris", and along with the fact that its seven different pieces (tetrominoes) are made up of 4 squares, is the basis of the game's title.[4]: 16

If the player cannot make the blocks disappear quickly enough, the field will start to fill; when the pieces reach the top of the field and prevent the arrival of additional pieces, the game ends.[3] At the end of each game, the player receives a score based on the number of lines that have been completed.[4]: 16 The game never ends with the player's victory, as the player can complete only as many lines as possible before an inevitable loss.[2]

Game pieces

[edit]

The pieces on which the game of Tetris is based around are called "tetrominoes". Pajitnov's original version for the Electronika 60 computer used green brackets to represent the blocks that make up tetrominoes.[6] Versions of Tetris on the original Game Boy/Game Boy Color and on most dedicated handheld games use black-and-white or grayscale graphics, but most popular versions use a separate color for each distinct shape. Prior to the Tetris Company's standardization in the early 2000s, those colors varied widely from implementation to implementation.

Scoring

[edit]The scoring formula for the majority of Tetris products is built on the idea that more difficult line clears should be awarded more points. For example, a single line clear in Tetris Zone is worth 100 points, clearing four lines at once (known as a Tetris) is worth 800, while each subsequent back-to-back Tetris is worth 1,200.[7] In conjunction, players can be awarded combos that exist in certain games which reward multiple line clears in quick succession. The exact combo system varies from game to game.[8]

Nearly all Tetris games allow the player to press a button to increase the speed of the current piece's descent or cause the piece to drop and lock into place immediately, known as a "soft drop" and a "hard drop", respectively. While performing a soft drop, the player can also stop the piece's increased speed by releasing the button before the piece settles into place. Some games allow only one of either soft drop or hard drop; others have separate buttons for each. Many games award a number of points based on the height that the piece fell before locking, so using the hard drop generally awards more points.

Easy spin dispute

[edit]"Easy spin", or "infinite spin",[9] is a feature in some Tetris games where a tetromino stops falling for a moment after left or right movement or rotation, effectively allowing the player to suspend the piece while deciding where to place it. The mechanic was introduced in 1999's The Next Tetris[citation needed] and drew criticism in reviews of 2001's Tetris Worlds.[9]

This feature has been implemented into the Tetris Company's official guideline.[10] This type of play differs from traditional Tetris because it takes away the pressure of higher-level speed. Some reviewers[11] went so far as to say that this mechanism broke the game. The goal in Tetris Worlds is to complete a certain number of lines as fast as possible, so the ability to hold off a piece's placement will not make achieving that goal any faster. Later, GameSpot received "easy spin" more openly, saying that "the infinite spin issue honestly really affects only a few of the single-player gameplay modes in Tetris DS, because any competitive mode requires you to lay down pieces as quickly as humanly possible".[12]

Henk Rogers told Nintendo World Report that infinite spin was an intentional part of the game design, allowing novice players to expend some of their available scoring time to decide on the best placement of a piece. He observed that "gratuitous spinning" does not occur in competitive play, as expert players do not require much time to think about where a piece should be placed. A limitation has been placed on infinite lock delay in later games of the franchise, where after a certain amount of rotations and movements, the piece will instantly lock itself. This is defaulted to 15 such actions.[10]

History

[edit]Conception and initial creation (1984–1985)

[edit]

In 1979, Alexey Pajitnov joined the Computer Center of the Soviet Academy of Sciences as a speech recognition researcher. While he was tasked with testing the capabilities of new hardware, his ambition was to use computers to make people happy.[13]: 85 Pajitnov developed several puzzle games on the institute's computer, an Electronika 60, a scarce resource at the time due in part to CoCom.[14]: 298 [15]1:50 For Pajitnov, "games allow people to get to know each other better and act as revealers of things you might not normally notice, such as their way of thinking".[13]: 85

In 1984,[16] while trying to recreate a favorite puzzle game from his childhood featuring pentominoes,[17] Pajitnov imagined a game consisting of a descent of random pieces that the player would turn to fill rows.[13]: 85 Pajitnov felt that the game would be needlessly complicated with twelve different shape variations, so he scaled the concept down to tetrominoes, of which there are seven variants.[18] Pajitnov titled the game Tetris, a word created from a combination of "tetra" (meaning "four") and his favorite sport, "tennis".[19][15]1:20

Because the Electronika 60 had no graphical interface, Pajitnov modelled the field and pieces using spaces and brackets[14]: 299 (45 lines of 80 ASCII characters).[15]1:50 Realizing that completed lines filled the screen quickly, Pajitnov decided to delete them, creating a key part of Tetris gameplay.[18] This early version of Tetris had no scoring system and no levels, but its addictive quality distinguished it from the other puzzle games Pajitnov had created.[20] Pajitnov wrote the game using Pascal for the RT-11 operating system on the Electronika 60.[15]1:50

Pajitnov had completed the first playable version of Tetris c. 1985.[16] Pajitnov presented Tetris to his colleagues, who quickly became addicted to it.[13]: 87 It permeated the offices within the Academy of Sciences, and within a few weeks it reached every Moscow institute with a computer.[13]: 87 [21]: 9 min A friend of Pajitnov, Vladimir Pokhilko, who requested the game for the Moscow Medical Institute, saw people stop working to play Tetris. Pokhilko eventually banned the game from the Medical Institute to restore productivity.[13]: 87

Pajitnov sought to adapt Tetris to the IBM Personal Computer, which had a higher quality display than the Electronika 60. Pajitnov recruited Vadim Gerasimov, a 16-year-old high school student who was known for his computer skills.[13]: 87 [14]: 300 Pajitnov had met Gerasimov before through a mutual acquaintance, and they had worked together on previous games.[6] Gerasimov adapted Tetris to the IBM PC over the course of a few weeks, incorporating color and a scoreboard.[14]: 300 The PC port was written with Turbo Pascal.[15]1:50

Alexey Pajitnov has given differing years on when his original version of Tetris was complete. In an interview published in 1993, he stated the game was not in a playable state until 1985 [16] Henk Rogers stated that the only information about the release is from Pajitnov's recollections, that he first developed it on the Electronica 60 in 1984 during a time when copyright notices were not a thing in the Soviet Union and that in 1985, Pajitnov says the IBM PC version was distributed in the Soviet Union.[16]

Spread beyond the Soviet Union (1985–1988)

[edit]Pajitnov wanted to export Tetris, but had no knowledge of the business world. His superiors in the Academy were not necessarily happy with the success of the game, since they had not intended such a creation from the research team.[13]: 87 Furthermore, copyright law of the Soviet Union created a state monopoly on import and export of copyrighted works, and the Soviet researchers were not allowed to sell their creations.[14]: 301 [21]: 10 min Pajitnov asked his supervisor Victor Brjabrin, who had knowledge of the world outside the Soviet Union, to help him publish Tetris. Pajitnov offered to transfer the rights of the game to the Academy, and was delighted to receive a non-compulsory remuneration from Brjabrin through this deal.[13]: 88

In 1986, Brjabrin sent a copy of Tetris to Hungarian game publisher Novotrade.[13]: 88 From there, copies of the game began circulating via floppy disks throughout Hungary and as far as Poland.[13]: 89 Robert Stein, an international software salesman for the London-based firm Andromeda Software, saw the game's commercial potential during a visit to Hungary in June 1986.[14]: 302 [21]: 11 min After an indifferent response from the Academy,[21]: 12 min Stein contacted Pajitnov and Brjabrin by fax to obtain the license rights.[21]: 11 min The researchers expressed interest in forming an agreement with Stein via fax, but they were unaware that this fax communication could be considered a legal contract in the Western world;[22] Stein began to approach other companies to produce the game.[13]: 89–90

Stein approached publishers at the 1987 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Gary Carlston, co-founder of Broderbund, retrieved a copy and brought it to California. Despite enthusiasm amongst its employees, Broderbund remained skeptical because of the game's Soviet origins. Likewise, Mastertronic co-founder Martin Alper declared that "no Soviet product will ever work in the Western world".[13]: 90 Carlston regretted turning down what he described as "the worldwide rights to Tetris for $50,000 ... People have tried to make me feel better about my decision by telling me about everything Henk Rogers went through to get the rights, but yeah, I should have accepted the game".[23]

Stein ultimately signed two agreements: he sold the European rights to the publisher Mirrorsoft[13]: 90 [24] and the American rights to sister company Spectrum HoloByte.[25] The latter obtained the rights after a visit to Mirrorsoft by Spectrum HoloByte president Phil Adam in which he played Tetris for two hours.[13]: 90 [21]: 15 min At that time, Stein had not yet signed a contract with the Soviet Union.[24] Nevertheless, he sold the rights to the two companies for £3,000 and a royalty of 7.5 to 15% on sales.[14]: 304

Before releasing Tetris in the United States, Spectrum HoloByte CEO Gilman Louie asked for an overhaul of the game's graphics and music.[13]: 90 The Soviet spirit was preserved, with fields illustrating Russian parks and buildings as well as melodies anchored in Russian folklore of the time. The company's goal was to make people want to buy a Russian product. The game came complete with a red package and Cyrillic text, an unusual approach on the other side of the Berlin Wall.[21]: 16 min The Mirrorsoft version was released in Europe on January 27, 1988,[26] and the Spectrum HoloByte version was released on January 29, 1988.[27] The game was first released for IBM PC DOS, with other platforms following over the next year.[28][13]: 91

Mirrorsoft ported Tetris to platforms including the Amiga, Atari ST, ZX Spectrum, Commodore 64 and Amstrad CPC. Tetris was a commercial success in Europe and the United States: Mirrorsoft sold tens of thousands of copies in two months,[13]: 91 and Spectrum HoloByte sold over 100,000 units in the space of a year.[21]: 18 min According to Spectrum HoloByte, the average Tetris player was between 25 and 45 years old and was a manager or engineer. At the Software Publishers Association's Excellence in Software Awards ceremony in March 1988, Tetris won Best Entertainment Software, Best Original Game, Best Strategy Program, and Best Consumer Software.[13]: 91

Stein was faced with a problem: the only document certifying a license fee was the fax from Pajitnov and Brjabrin, meaning that Stein sold the license for a game he did not yet own. Stein contacted Pajitnov and asked him for a contract for the rights. Stein began negotiations via fax, offering 75% of the revenue generated by Stein from the license.[14]: 304 Elektronorgtechnica ("Elorg"), the Soviet Union's central organization for the import and export of computer software, was unconvinced and requested 80% of the revenue. Stein made several trips to Moscow and held long discussions with Elorg representatives.[14]: 305

Stein came to an agreement with Elorg on February 24, 1988.[14]: 308 On May 10[21]: 22 min he signed a contract for a ten-year worldwide Tetris license for all current and future computer systems.[13]: 92 Pajitnov and Brjabrin were unaware that the game was already on sale and that Stein had claimed to own the rights prior to the agreement.[24] Although Pajitnov did not receive any percentage from these sales,[13]: 92 he said that "the fact that so many people enjoy my game is enough for me".[13]: 96

Legal battles (1988–1989)

[edit]

In 1988, Spectrum HoloByte sold the Japanese rights to its computer games to Bullet-Proof Software's Henk Rogers, who was searching for games for the Japanese market.[21]: 22 min Mirrorsoft sold arcade rights to Atari Games subsidiary Tengen, which then sold the Japanese arcade rights to Sega and the console rights to BPS, which published versions for Japanese computers, including the MSX2, PC-88 and X68000, along with a console port for the Nintendo Family Computer (Famicom), known outside Japan as the Nintendo Entertainment System.[29]: 480 The Japanese port was written in C[15]2:55 and in 6502 assembly language for Nintendo.[15]3:05

At this point, almost a dozen companies believed they held the Tetris rights, with Stein retaining rights for home computer versions.[29]: 480 The Soviet Union's Elorg was still unaware of the deals Stein had negotiated, which did not bring money to them. Tetris was a commercial success in North America, Europe and Asia.[21]: 22 min

The same year, Nintendo was preparing to launch its first portable console, the Game Boy. Nintendo was attracted to Tetris by its simplicity and established success on the Famicom.[13]: 92 [29]: 480 Rogers, who was close to then Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi, sought to obtain the handheld rights.[13]: 92 After a failed negotiation with Atari,[13]: 93 Rogers contacted Stein in November 1988. Stein agreed to sign a contract, but explained that he had to consult Elorg before returning to negotiations with Rogers.[21]: 24 min [14]: 313 After contacting Stein several times, Rogers began to suspect a breach of contract on Stein's part, and he decided in February 1989 to go to the Soviet Union and negotiate the rights with Elorg.[13]: 93 [14]: 313

Rogers arrived at the Elorg offices uninvited, while Stein and Mirrorsoft manager Kevin Maxwell made an appointment the same day without consulting each other.[21]: 29 min During the discussions, Rogers explained that he wanted to obtain the rights to Tetris for the Game Boy.[13]: 95 After quickly obtaining an agreement with Elorg president Nikolai Belikov,[14]: 316 Rogers showed Belikov a Famicom Tetris cartridge.[13]: 94 Belikov was surprised, as he believed at the time that the rights to Tetris were only signed for computer systems.[21]: 31 min

The present parties accused Rogers of illegal publication, but Rogers defended himself by explaining that he had obtained the rights via Atari Games, which had itself signed an agreement with Stein.[13]: 94 Belikov then realized the complex path that the license had followed within four years because of Stein's contracts, and he constructed a strategy to regain possession of the rights and obtain better commercial agreements. At that point, Elorg was faced with three different companies seeking to buy the rights.[21]: 35 min

During this time, Rogers befriended Pajitnov over a game of Go. Pajitnov supported Rogers throughout the discussions, to the detriment of Maxwell, who had come to secure the console rights for Mirrorsoft.[13]: 93 Belikov proposed to Rogers that Stein's rights would be cancelled and Nintendo would be granted the game rights for both home and handheld consoles.[13]: 94 Rogers flew to the United States to convince Nintendo's American branch to sign up for the rights. The contract with Elorg was signed by executive and president Minoru Arakawa for $500,000, plus 50 cents per cartridge sold.[13]: 95 [21]: 42 min

Elorg then sent an updated contract to Stein. One of the clauses defined a computer as a machine with a screen and keyboard, and thus Stein's rights to console versions were withdrawn.[21]: 37 min Stein signed the contract without paying attention to this clause[13]: 95 and later realized that all the contract's other clauses, notably on payments, were only a "smokescreen" to deceive him.[21]: 37 min [14]: 319

In March 1989, Nintendo sent a cease and desist to Atari Games concerning production of the NES version of Tetris.[21]: 47 min Atari Games contacted Mirrorsoft and were assured that they still retained the rights. Nintendo maintained its position. In response, Mirrorsoft owner Robert Maxwell pressured Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev to cancel the contract between Elorg and Nintendo.[13]: 95 Despite the threats to Belikov, Elorg refused to give in and highlighted the financial advantages of their contract compared to those signed with Stein and Mirrorsoft.[13]: 95 [21]: 45 min

On June 15, 1989, Nintendo and Atari Games began a legal battle in the courts of San Francisco. Atari Games sought to prove that the NES was a computer, as indicated by its Japanese name "Famicom", an abbreviation of "Family Computer". In this case, the initial license would authorize Atari Games to release the game. The central argument of Atari Games was that the Famicom could be converted into a computer via the Family BASIC peripheral. This argument was not accepted, and Pajitnov stressed that the initial contract only concerned computers and no other machine.[13]: 96

Nintendo brought Belikov to testify on its behalf.[21]: 48 min Judge Fern M. Smith declared that Mirrorsoft and Spectrum HoloByte never received explicit authorization for marketing on consoles, and, on June 21, 1989, ruled in Nintendo's favor, granting them a preliminary injunction against Atari Games in the process.[13]: 96 The next day, Atari Games withdrew its NES version from sale, and thousands of cartridges remained unsold in the company's warehouses.[30][31]

Sega had planned to release a Genesis version of Tetris on April 15, 1989, but cancelled its release during Nintendo and Atari's legal battle;[32] fewer than ten copies were manufactured.[33] The Game Boy version of Tetris was released in Japan in June 1989[34] and as a pack-in title in the United States in July 1989.[35] The NES version was released the same year. Both versions achieved much commercial success, with the Game Boy version selling more than 40 million sales and the NES version selling more than 7 million.[36]

Post-legal battles and The Tetris Company (1989–present)

[edit]

Through the legal history of the license, Pajitnov gained a reputation in the West. He was regularly invited by journalists and publishers, through which he discovered that Tetris had sold millions of copies, from which he had not made any money. He took pride in the game, which he considered "an electronic ambassador of benevolence".[13]: 96 In January 1990, Pajitnov was invited by Spectrum HoloByte to the Consumer Electronics Show, and he was immersed in American life for the first time.[13]: 97 After a period of adaptation, he explored American culture in several cities, including Las Vegas, San Francisco, New York City and Boston. He engaged in interviews with several hosts, including the directors of Nintendo of America.[14]: 347 He marveled at the freedom and the advantages of Western society, and, upon returning to the Soviet Union, he spoke often of his travels to his colleagues. He realized that there was no market in Russia for their programs.[13]: 97 In 1991, Pajitnov and Pokhilko emigrated to the United States.[13]: 97 Pajitnov moved to Seattle, where he produced games for Spectrum HoloByte.[37] Several versions were produced during this time, including Spectrum Holobyte's Welltris (1990) and Super Tetris (1991), Bullet-Proof Software's Tetris 2 + BomBliss (1991) and Tetris Battle Gaiden (1993), and Nintendo's Tetris 2 (1993).[38]

In April 1996, as agreed with the Academy ten years earlier and following an agreement with Rogers, the rights to Tetris reverted to Pajitnov.[37] Pajitnov and Rogers founded the Tetris Company in June 1996 to manage the rights on all platforms, the previous agreements having expired. Pajitnov now receives a royalty for each Tetris game and derivative sold worldwide.[13]: 100 Since 1996, the Tetris Company has internally defined specifications and guidelines to which publishers must adhere to be granted a license to Tetris, known as the Tetris guidelines. The contents of these guidelines establish elements such as the correspondence of buttons and actions, the size of the field of play, and the system of rotation.[39][10][20]

In 2002, Pajitnov and Rogers founded Tetris Holding after the purchase of the game's remaining rights from Elorg, now a private entity following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The Tetris Company now owns all rights to the Tetris brand, and it is mainly responsible for removing unlicensed clones from the market.[37][13]: 100 Since the 2000s, internet versions of the game have been developed. Commercial versions not approved by the Tetris Company tend to be purged due to company policy, and the company regularly calls on Apple Inc. and Google to remove illegal versions from their mobile app stores.[40][41] In one notable 2012 case, Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc., Tetris Holding and the Tetris Company defended its copyright against an iOS clone, which established a new stance on evaluating video game clone infringements based on look and feel.[42]

In December 2005, Electronic Arts acquired Jamdat, a company specializing in mobile games.[43] Jamdat had previously bought a company founded by Rogers in 2001 which managed the Tetris license on mobile platforms. As a result, Electronic Arts held a 15-year license on all mobile phone releases of Tetris,[37] which expired on April 21, 2020.[44]

Versions

[edit]

Tetris has been released on a multitude of platforms since the creation of the original version on the Electronika 60. The game is available on most game consoles and is playable on personal computers, smartphones and iPods. Guinness World Records recognized Tetris as the most ported video game in history, with over 200 variants having appeared on over 65 different platforms as of October 2010.[45] By 2017 this number had increased to 220 official variants.[46]

Within official franchise installments, each version has made improvements to accommodate advancing technology and the goal to provide a more complete game. Developers are given freedom to add new modes of play and revisit the concept from different angles. Some concepts developed on official versions have been integrated into the Tetris guidelines in order to standardize future versions and allow players to migrate between different versions with little effort.[10] The IBM PC version was the most evolved from the original version, featuring a graphical interface, colored tetrominoes, running statistics for the number of tetrominoes placed, and a guide for the controls.[6]

Music

[edit]The earliest versions of Tetris had no music.[15]3:10 Spectrum Holobyte's version of Tetris in the United States exoticized the game's Soviet origins through elements such as Russian music, including Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's "Trepak" from The Nutcracker and Reinhold Glière's "Russian Sailor Dance" from The Red Poppy. This approached differed from other versions of Tetris from other countries at the time: Mirrosoft's Commodore 64 version in Europe used an atmospheric soundtrack, and Sega's arcade version in Japan used a synthesized pop-influenced soundtrack.[47]

Nintendo's versions for NES and Game Boy continued the pattern of using Russian music. The NES version uses Tchaikovsky's "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" from The Nutcracker as Music A, with the Russian-influenced Music B and the mellow Music C having unclear origins.[48] The Game Boy version consists of the 1860s Russian folk tune "Korobeiniki" for Music A, an original composition by Hirokazu Tanaka for Music B, and the Menuet of Johann Sebastian Bach's French Suite no. 3 for Music C.[49] "Korobeiniki" has become primarily associated with Tetris as its main theme and would be used in most significant versions of the game,[50][47] as mandated by the Tetris Guidelines. Doctor Spin's 1992 Eurodance cover (under the name "Tetris") reached #6 on the UK singles chart.[20]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Initial reviews

[edit]| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | Arcade: C64: Macintosh: NES (Tengen): NES (Nintendo): |

| Crash | 77%[57] |

| Computer and Video Games | 94%[56] |

| Sinclair User | |

| Your Sinclair | 9/10[59] |

| Zzap!64 | 98%[60] |

| ACE | 95%[61] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Zzap!64 | Gold Medal |

| Sinclair User | SU Classic |

The IBM version received positive reviews. Compute! called it "one of the most addictive computer games this side of the Berlin Wall ... [it] is not the game to start if you have work to do or an appointment to keep. Consider yourself warned".[62] Orson Scott Card joked that the game "proves that Russia still wants to bury us. I shudder to think of the blow to our economy as computer productivity drops to 0". Noting that Tetris was not copy-protected, he wrote: "Obviously, the game is meant to find its way onto every American machine".[63] Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser in "The Role of Computers" column of Dragon No. 135 gave the version 4.5 out of 5 stars.[64] Roy Wagner reviewed the game for Computer Gaming World the same year, and said that "Tetris is simple in concept, simple to play, and a unique design".[65]

The Macintosh version also received positive reviews. Macworld praised its strategic gameplay, stating that "Tetris offers the rare combination of being simple to learn but extremely challenging to play", and also praising the inclusion of the Desk Accessory version, which uses less RAM. Macworld summarized their review by listing Tetris' pros and cons, stating that Tetris is "elegant; easy to play; challenging and addicting; requires quick thinking, long-term strategy, and lightning reflexes" and listed Tetris' cons as "None".[66] The Lessers gave the version 5 out of 5 stars in Dragon No. 141.[67]

In their June 1989 issue, Zzap!64 awarded the Commodore 64 version a score of 98%, the joint highest score in the history of the magazine.[60]

Sales

[edit]Spectrum HoloByte's versions for personal computers sold 150,000 copies for $6 million ($15 million adjusted for inflation) in two years, between 1988 and 1990.[68] By 1995, the versions sold more than 1 million copies, with women accounting for nearly half of Tetris players, in contrast to most other PC games.[69]

Tetris gained greater success with the release of Nintendo's NES version and Game Boy version in 1989. In six months of release by 1990, the NES version sold 1.5 million copies for $52 million ($128 million adjusted for inflation), while Game Boy bundles with Tetris sold 2 million units.[68] It topped the Japanese sales charts during August–September 1989[70][71] and from December 1989 to January 1990.[72] Tetris became Nintendo's top seller for the first few months of 1990.[73] Nintendo's versions of Tetris sold 7.5 million copies in the United States by 1992,[74] and more than 20 million worldwide by 1996.[75] Nintendo eventually sold a total of 35 million copies for the Game Boy,[76] and 8 million for the NES.[21]: 51 min

By January 2010, the Tetris franchise had sold more than 170 million copies, including approximately 70 million physical copies and over 100 million copies for cell phones.[20][77] In April 2014, Rogers announced in an interview with VentureBeat that Tetris totaled 425 million paid mobile downloads and 70 million physical copies.[78][79] To date, the Tetris franchise is the third-best-selling video game franchise of all time, totaling 520 million sales according to the Tetris Company.[80][81] A majority originate from paid mobile downloads, based on Rogers' figure from the 2014 interview.[79][82] As a result, some publications consider Tetris to be the best-selling game of all time, despite variations among the different versions.[80][81]

Accolades

[edit]Tetris garnered awards from early on. The game won three Software Publishers Association Excellence in Software Awards in 1989, including Best Entertainment Program and the Critic's Choice Award for consumers.[83] Macworld inducted Tetris into the 1988 Macworld Game Hall of Fame in the Best Strategy Game category. Macworld praised "the addictive quality of the game" and said its "simplicity is bewitching."[84] and Computer Gaming World gave Tetris the 1989 Compute! Choice Award for Arcade Game, describing it as "by far, the most addictive game ever".[85] Entertainment Weekly picked the game as the #8 greatest game available in 1991, saying: "Thanks to Nintendo's endless promotion, Tetris has become one of the most popular video games".[86]

Tetris has been widely ranked as among the greatest video games of all time by Flux (1995),[87] Next Generation (1996 and 1999),[88][89] Electronic Gaming Monthly (1997),[90] GameSpot (2000),[91] Game Informer (2001 and 2009),[92][93] IGN (2007 and 2021),[94][95] Time (2012 and 2016),[96][97] GamesRadar+ (2015 and 2021),[98][99] Polygon (2017),[100] USA Today (2022 and 2024),[101][102] The Times (2023),[103] and GQ (2023).[104] Tetris has also been ranked as among the best computer games by PC Format (1991)[105] and Computer Gaming World (1996).[106] In 1993, the ZX Spectrum version of the game was voted number 49 in the Your Sinclair Official Top 100 Games of All Time.[107] In 1996, Tetris Pro was ranked the 38th best game of all time by Amiga Power.[108]

Tetris has been inducted into the "Hall of Fame" of the following publications: Computer Gaming World (1999),[109] GameSpy (2000),[110] GameSpot (2003),[111] and IGN (2007).[112] On March 12, 2007, The New York Times reported that Tetris was named to a list of the ten most important video games of all time, the so-called game canon.[113] After announced at the 2007 Game Developers Conference, the Library of Congress took up the video game preservation proposal and began with these 10 games, including Tetris.[114][115] In 2015, The Strong National Museum of Play inducted Tetris to its World Video Game Hall of Fame.[116]

Cultural impact

[edit]Tetris's cultural impact and recognition is widespread, as demonstrated by its continuing commercial success and representation in a vast array of media such as architecture and art.[117][20] Tetris has over 200 official variants across 70 platforms to date, a record acknowledged by the Guinness World Record.[118] Tetris is widely seen as a " simple but addictive" game,[119] and has been the subject of academic research in psychology and mathematics.[120][121][122] Writers such as Dan Ackerman have attributed the enduring success of Tetris to its appeal to casual gamers.[123]

Tetris has a competitive scene, primarily centering around the Classic Tetris World Championship (CTWC). Competitor Jonas Neubauer and his victory in the inaugural CTWC in 2010 were the subject of the 2011 documentary Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters.[124] Competitors of the CTWC, typically adolescents, have used the CTWC to demonstrate advancements in the gameplay of the NES version. For example, gameplay techniques such as "hypertapping" and "rolling" have been used to help competitors to maximize their scores beyond level 29, which was previously deemed impossible to complete due to its speed.[125][126] The "beating" of Tetris, accomplished by competitor Willis Gibson by playing NES Tetris until it crashed in a 40-minute livestream, received significant media coverage in January 2024.[118][127]

In 2014 it was announced that Threshold Entertainment had teamed up with the Tetris Company to develop a film adaptation of the game. CEO Larry Kasanoff called it an epic sci-fi adventure and the first part of a trilogy.[128][129] In 2016, a press release falsely claimed the film would be shot in China in 2017 with an $80 million budget.[130] A movie titled Tetris, about the legal battle surrounding the game in the late 1980s and starring Taron Egerton as Henk Rogers,[131] premiered on Apple TV+ on March 31, 2023.[132][133]

Research

[edit]Tetris has been the subject of academic research. Vladimir Pokhilko was the first clinical psychologist to conduct experiments using Tetris.[119] Subsequently, it has been used for research in several fields including the theory of computation, algorithmic theory, and cognitive psychology.

Psychological research

[edit]The psychological and addictive effects of Tetris were first scientifically recognized by Pokhilko.[134][119] Pokhilko was reportedly recipient of Tetris. Interested in its potential psychological effects based on his experiences playing the game, Pokhilko distributed copies of Tetris to his colleagues at the Moscow Medical Center. Pokhilko regretted his decision after constant gameplay impaired medical research and proceeded to destroy the distributed copies. After new copies were reintroduced to his facility, Pokhilko used Tetris in his testing of patients.[135]

Starting with the research of American psychologist Richard J. Haier in 1992,[136][137][138] Tetris has been frequently used as a form of cognitive assessment and neuroimaging.[139][140] Furthermore, Tetris has been studied as a potential form of psychological intervention such as for PTSD and cravings with promising results.[139][141] The "Tetris effect" refers to the phenomena of perceiving certain patterns in dreams and mental images following engagement in a repetitive activity such as playing Tetris,[134][142] and was first coined by Jeffrey Goldsmith in a 1994 article for Wired, in which he compared Tetris to an "electronic drug".[143][144]

Research in computer science

[edit]In 1992, John Brzustowski at the University of British Columbia wrote a thesis reflecting on the question of whether or not one could theoretically play Tetris forever.[145] He reached the conclusion that the game is statistically doomed to end. If a player receives a sufficiently large sequence of alternating S and Z tetrominoes, the naïve gravity used by the standard game eventually forces the player to leave holes on the board. The holes will necessarily stack to the top and, ultimately, end the game. If the pieces are distributed randomly, this sequence will eventually occur. Thus, if a game with, for example, an ideal, uniform, uncorrelated random number generator is played long enough, any player will almost surely top out.[146][147]

In computer science, it is common to analyze the computational complexity of problems, including real-life problems and games. In 2001, a group of MIT researchers proved that for the "offline" version of Tetris (the player knows the complete sequence of pieces that will be dropped, i.e. there is no hidden information) the following objectives are NP-complete:

- Maximizing the number of rows cleared while playing the given piece sequence.

- Maximizing the number of pieces placed before a loss occurs.

- Maximizing the number of simultaneous clearing of four rows.

- Minimizing the height of the highest filled grid square over the course of the sequence.

Also, it is difficult to even approximately solve the first, second, and fourth problem. It is NP-hard, given an initial gameboard and a sequence of p pieces, to approximate the first two problems to within a factor of p1 − ε for any constant ε > 0. It is NP-hard to approximate the last problem within a factor of 2 − ε for any constant ε > 0. To prove NP-completeness, it was shown that there is a polynomial reduction between the 3-partition problem, which is also NP-complete, and the Tetris problem.[148][149]

Thermodynamics simulation

[edit]During the game of Tetris, blocks appear to adsorb onto the lower surface of the window. This has led scientists to use tetrominoes "as a proxy for molecules with a complex shape" to model their "adsorption on a flat surface" to study the thermodynamics of nanoparticles.[150][151]

See also

[edit]- Brain Wall and Blokken, game shows based on Tetris

- Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters, a 2011 documentary about the 2010 Classic Tetris World Championship, featuring interviews with Pajitnov and Richard Haier as well as Tetris players Thor Aackerlund and future seven-time Classic Tetris World Championship champion Jonas Neubauer

- Game Over (Sheff book), a 1993 book covering Nintendo history, including interviews with Pajitnov and others regarding Tetris licensing

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pronounced [ˈtʲetrʲɪs] or [ˈtetrʲɪs]

References

[edit]- ^ "Tetris | video game | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c Kent 2001, p. 377.

- ^ a b c d "About Tetris". The Tetris Company. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Tetris (Game Boy instruction booklet).

- ^ Tetris DS (Instruction booklet). p. 6.

- ^ a b c Gerasimov, Vadim. "Original Tetris: Story and Download". Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ "Tetris Zone Manual". Tetris Zone. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009.

- ^ Ramos, Jeff (March 6, 2019). "Tetris advanced guide: T-spins, perfect clears, and combos". Polygon. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Davis, Ryan (September 5, 2001). "Tetris Worlds for Game Boy Advance Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 28, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Metts, Jonathan (April 6, 2006). "Tetris from the Top: An Interview with Henk Rogers". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ Jeff Gerstmann; Ryan Davis (April 19, 2002). "Tetris Worlds for PlayStation 2 Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ^ Davis, Ryan (March 20, 2006). "Tetris DS Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Ichbiah, Daniel (1997). La Saga des Jeux Vidéo (in French) (1st ed.). Pix'N Love Editions. ISBN 2266087630.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Sheff, David; Eddy, Andy (1999). Game Over: Press Start to Continue (1st ed.). Cyberactive Media Group. ISBN 0966961706.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Unsolved Tetris Mysteries With Creator Alexy Pajitnov & Designer Henk Rogers" (Video). Ars Technica. April 26, 2023. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d McFerran, Damien; Yarwood, Jack (June 24, 2024). "Anniversary: Is Tetris Really 40 This Year?". Time Extension. Archived from the original on July 17, 2024. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ Fries, Matt Beer and Jacob (September 24, 1998). "Pushed past the brink". SFGATE. Archived from the original on July 15, 2024. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Hoad, Phil (June 2, 2014). "Tetris: how we made the addictive computer game | Culture". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ^ "About Tetris". Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Bobbie (June 1, 2009). "How Tetris conquered the world, block by block". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Temple, Magnus (2004). Tetris: From Russia with Love (Documentary).

- ^ Temple 2004, 12 min..

- ^ "A chat with Gary Carlston of Brøderbund". Spillhistorie.no. June 19, 2024. Archived from the original on September 3, 2024. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c Kent 2001, p. 479.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 294,479.

- ^ "Soviets Play Capitalist Game With New Computer Puzzle". The Los Angeles Times. January 28, 1988. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

- ^ Lewis, Peter H. (January 29, 1988). "New Software Game: It Comes From Soviet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2009). Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of the Most Influential Games of All Time (1st ed.). Focal Press. ISBN 978-0240811468.

- ^ "From Russia with Litigation". Next Generation. No. 26. Imagine Media. February 1997. p. 42.

- ^ "The Wish List". Edge Presents Retro. 2002.

- ^ "Game Machine: "Nintendo Offers Home Video Game Tetris"" (PDF). Amusement Press. May 1, 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (July 18, 2011). "You Could Own This Copy of Tetris for Only $1,000,000". Kotaku. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ ゲームボーイ (in Japanese). Nintendo. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (July 27, 2009). "IGN Presents the History of Game Boy". IGN. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 379–380.

- ^ a b c d "The Story of Tetris: Henk Rogers (Part 5)". Sramana Mitra. September 20, 2009. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Crookes, David (September 2018). "The History of Tetris". Retro Gamer. No. 183. pp. 20–29.

- ^ "History of Tetris". The Tetris Company. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Chartier, David (October 8, 2008). "Tetris Co. strikes again: another iPhone app clone is pulled". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Ryan, Paul (June 2, 2010). "Google blocks Tetris clones from Android market". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on December 2, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ Brown, Mark (June 21, 2012). "Judge Declares iOS Tetris Clone 'Infringing'". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "EA to Acquire JAMDAT Mobile Inc. -- the Leader in North American Mobile Interactive Entertainment; Accelerates EA's Objective of Global Expansion in Mobile". Business Wire. December 8, 2005. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Christine (January 22, 2020). "EA is shutting down its mobile Tetris games". Engadget. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Most ported computer game". Guinness World Records. October 1, 2010. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "Most variants of a videogame". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ a b Plank-Blasko, Dana (October 2015). "'From Russia with Fun!': Tetris, Korobeiniki and the ludic Soviet". The Soundtrack. 8 (1–2): 7–24. doi:10.1386/st.8.1-2.7_1. Archived from the original on July 10, 2024. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ Gibbons, William (Spring 2009). "Blip, Bloop, Bach? Some Uses of Classical Music on the Nintendo Entertainment System". Music and the Moving Image. 2 (1): 40–52. doi:10.5406/musimoviimag.2.1.0040. Archived from the original on January 7, 2024. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ Plank 2022, p. 269.

- ^ Ackerman 2016, p. 97.

- ^ Cook, Brad. "Tetris". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ Sutyak, Jonathan. "Tetris". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ Savignano, Lisa Karen. "Tetris". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Skyler. "Tetris". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ Weiss, Brett Alan. "Tetris". AllGame. Archived from the original on February 16, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ "Tetris Mastertronic". Computer and Video Games. No. 92. June 1989. p. 74. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ "Reviews: Tetris". Crash. No. 50. March 1988. p. 10. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ "TETЯIS: Arcade Review". Sinclair User. February 1988. p. 13. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Worrall, Tony. "Tetris". The Your Sinclair Rock'n'Roll Years. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ a b "Gold Standard". The Def Gui to Zzap!64. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "Tetris: Can MIRRORSOFT pack them in?". ACE. February 1988. p. 49. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Weatherman, Lynne (July 1988). "Tetris". Compute!. p. 72. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Card, Orson Scott (April 1989). "Gameplay". Compute!. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (July 1988). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (135): 82–89.

- ^ Wagner, Roy (May 1988). "Puzzling Encounters: Two Titles from Spectrum HoloByte's International Series". Computer Gaming World. Vol. 1, no. 47. pp. 42–43.

- ^ Buderi, Robert (December 1988). "Tetris 1.0 Review". Macworld. Mac Publishing. p. 178.

- ^ Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (January 1989). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (141): 72–78.

- ^ a b Dvorchak, Robert (June 17, 1990). "Soviet Game Conquers the Free Market : Technology: Tetris, an electronic Rubik's Cube, proves to be addictive. Sales are sizzling. Sequel is coming from East Bloc". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ McGowan, Chris; McCullaugh, Jim (1995). Entertainment in the Cyber Zone. Random House Electronic Pub. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-679-75804-4.

Spectrum HoloByte claims that nearly half of Tetris players are women, a striking contrast to the profiles of most other computer games. Since 1988, the company claims to have sold more than a million copies of Tetris-family PC products.

- ^ "ファミコン通信 TOP 30" [Famicom Tsūshin Top 30]. Famicom Tsūshin. Vol. 1989, no. 19. September 15, 1989.

- ^ "ファミコン通信 TOP 30" [Famicom Tsūshin Top 30]. Famicom Tsūshin. Vol. 1989, no. 22. October 27, 1989.

- ^ "Weekly Famimaga Hit Chart! (12/25~1/28)". Family Computer Magazine (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. February 23, 1990. pp. 134–6.

- ^ "Surviving Together". Surviving Together. 20–22. Committee and the Institute: 68. 1990.

2.5 million copies later, Tetris is Nintendo's top-selling title for the first few months of 1990.

- ^ Weaver, Kitty D. (1992). Bushels of Rubles: Soviet Youth in Transition. Praeger Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-275-93844-4.

"If I had known it would make big money, I wouldn't have given all the rights," he says, contemplating sales of 7.5 million copies in the United States, where Tetris is standard equipment for the Nintendo Game Boy hand-held unit.

- ^ "Sputnik: Digest". Sputnik: Digest (10–12). Novosti Printing House: 37. 1996.

Tetris became a bestseller. More than twenty million copies, not to count pirate ones, have already been sold.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (June 6, 2014). "Tetris at 30: a history of the world's most successful game". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "» Tetris atteint les 100 millions de téléchargements payants (et une petite histoire du jeu) – Maximejohnson.com/techno : actualités technologiques, tests et opinions par le j". Maximejohnson.com. January 19, 2011. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Rogers, Henk (April 7, 2014). "'Mr. Tetris' explains why the puzzle game is still popular after three decades". VentureBeat (Interview). Interviewed by Dean Takahashi. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Corriea, Alexa Ray (April 8, 2014). "Tetris has passed 425 million downloads on mobile, not including free-to-play". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Gerken, Tom (October 16, 2023). "Minecraft becomes first video game to hit 300m sales". BBC. Archived from the original on August 23, 2024. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Nguyen, Britney (October 16, 2023). "Minecraft Just Surpassed 300 Million Sales—Here's The Only Video Game Still Beating It". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 26, 2024. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Barr, Kyle (October 16, 2023). "Minecraft Is the Highest-Selling Game of All Time, Behind Tetris". Gizmondo. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Scisco, Peter (August 1989). "the Envelope, Please". Compute!. p. 6. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ Levy, Steven (December 1988). "The Game Hall of Fame". Macworld. Vol. 5, no. 12. San Francisco, CA: PCW Communications, Inc. p. 124.

- ^ "The 189 Compute! Choice Awards". Compute!. January 1989. p. 24. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Video Games Guide". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Video Games". Flux. No. 4. Harris Publications. April 1995. p. 28.

- ^ "Top 100 Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 21. Imagine Media. September 1996. p. 71.

- ^ "Top 50 Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 50. Imagine Media. February 1999. p. 81.

- ^ "100 Best Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 100. Ziff Davis. November 1997. p. 160. Note: Contrary to the title, the intro to the article (on page 100) explicitly states that the list covers console video games only, meaning PC games and arcade games were not eligible.

- ^ "The 100 Games of the Millennium - 39. Tetris". GameSpot. January 2, 2000. Archived from the original on June 12, 2000. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Cork, Jeff (November 16, 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ The Game Informer staff (December 2009). "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79. ISSN 1067-6392. OCLC 27315596.

- ^ "IGN Top 100 Games of All Time – 2007". Top100.ign.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Sullivan, Meghan (December 31, 2021). "The Top 100 Video Games of All Time - 28. Tetris". IGN. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "All-TIME 100 Video Games - Tetris". Time. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "The 50 Best Video Games of All Time". Time. August 23, 2016. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "The 100 best games ever". GamesRadar+. February 25, 2015. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "The 50 best games of all time". GamesRadar+. November 23, 2021. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "The 500 best games of all time: 100-1". Polygon. December 1, 2017. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "The 100 best video games of all time, ranked". USA Today. September 10, 2022. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "A definitive ranking of the top 30 video games of all time". USA Today. January 26, 2024. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Pebble, Lucy (February 26, 2023). "20 best video games of all time — 4. Tetris". The Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "The 100 greatest video games of all time, ranked by experts". British GQ. May 10, 2023. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Staff (October 1991). "The 50 best games EVER!". PC Format (1): 109–111.

- ^ "The 15 Most Innovative Computer Games". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. p. 102. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "Top 100 Games of All Time". Your Sinclair. September 1993.

- ^ Amiga Power magazine issue 64, Future Publishing, August 1996

- ^ "Hall of Fame — New Inductees - Tetris (Spectrum Holobyte 1988)". Computer Gaming World. No. 177. April 1999. p. 237.

- ^ "The Gamespy Hall of Fame - Tetris". Gamespy. July 2000. Archived from the original on July 6, 2004. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "They'll Keep Playing It Long After All of Us Are Dead". GameSpot. July 2, 2003. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "IGN Hall of Fame - Tetris". 2007. Archived from the original on May 6, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ CHAPLIN, HEATHER (March 12, 2007). "Is That Just Some Game? No, It's a Cultural Artifact". nytimes.com. Archived from the original on December 4, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Ransom-Wiley, James. "10 most important video games of all time, as judged by 2 designers, 2 academics, and 1 lowly blogger". Joystiq. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014.

- ^ Owens, Trevor (September 26, 2012). "Yes, The Library of Congress Has Video Games: An Interview with David Gibson". blogs.loc.gov. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ "Tetris". The Strong National Museum of Play. The Strong. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Ackerman 2016, p. 242–243.

- ^ a b Korn, Jennifer (January 3, 2024). "Oklahoma teenager finally defeats the unbeatable game: Tetris". CNN. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Mark J. P. Wolf (August 31, 2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming. ABC-CLIO. pp. 640–642. ISBN 978-0-313-37936-9. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Brown, Tracy (March 31, 2023). "What makes Tetris 'the perfect game'? Experts break down an addictive classic". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Scarle, Simon (April 12, 2023). "Tetris movie: why the story of the game's origins is legendary". The Conversation. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ McCoy, Leah (February 28, 2024). "Anyone can play Tetris, but architects, engineers and animators alike use the math concepts underlying the game". The Conversation. Archived from the original on November 13, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Hobbs, Thomas (March 29, 2023). "Why Tetris is the 'perfect' video game". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Schonbrun, Zach (December 28, 2021). "A New Generation Stacks Up Championships in an Old Game: Tetris". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Karnadi, Chris (June 21, 2022). "Teens are rewriting what is possible in the world of competitive Tetris". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Shaver, Morgan (March 31, 2023). "Why Tetris Consumed Your Brain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Water cutter, Angela (January 5, 2024). "Why Everyone Is Obsessed With the Kid Who Beat Tetris". Wired. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "'Tetris' Movie Planned as an Epic Sci-Fi Adventure". Movieweb. September 30, 2014. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Brzeski, Patrick (May 17, 2016). "'Tetris' Movie to Be $80M U.S.-China Co-Production". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 18, 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ Dickey, Josh (May 17, 2016). "Is this 'Tetris' movie for real? Too many key blocks are missing to be sure". Mashable. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "Taron Egerton to star in Tetris movie". List.co.uk. July 17, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "Apple Original Films unveils trailer for "Tetris," new thriller starring Taron Egerton". Apple TV+ Press. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Pingitore, Silvia (March 19, 2023). "Interview with Tetris creator Alexey Pajitnov". Archived from the original on June 26, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Ackerman 2016, p. 73.

- ^ Ackerman 2016, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Haier RJ, Siegel BV, MacLachlan A, Soderling E, Lottenberg S, Buchsbaum MS (January 1992). "Regional glucose metabolic changes after learning a complex visuospatial/motor task: a positron emission tomographic study". Brain Res. 570 (1–2): 134–43. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(92)90573-R. PMID 1617405. S2CID 21725897.

- ^ Ackerman 2016, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Latham, Andrew J.; Patson, Lucy L. M.; Tippette, Lynette J. (September 13, 2013). "The virtual brain: 30 years of video-game play and cognitive abilities". Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 629. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00629. PMC 3772618. PMID 24062712.

- ^ a b Agren, Thomas; Hoppe, Johanna M.; Singh, Laura; Holmes, Emily A.; Rosén, Jörgen (August 2, 2021). "The neural basis of Tetris gameplay: implicating the role of visuospatial processing". Current Psychology. 42 (10): 8156–8163. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02081-z. Archived from the original on November 13, 2024. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Lindstedt, John K.; Gray, Wayne D. (March 12, 2015). "Meta-T: TetrisⓇ as an experimental paradigm for cognitive skills research". Behavior Research Methods. 47 (4): 945–965. doi:10.3758/s13428-014-0547-y. PMID 25761389. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Plank 2022, p. 271.

- ^ McCluskey, Megan (March 31, 2023). "The Complicated True Story Behind Apple TV+'s Tetris Movie". Time. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ Ackerman 2016, p. 77–78.

- ^ Goldsmith, Jeffrey. "This Is Your Brain on Tetris". Wired. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ Brzustowski, John (March 1992). Can you win at Tetris? (PDF) (Master of Science thesis). University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2013. Alt URL

- ^ Burgiel, Heidi (January 7, 1996). "Discussion of the Tetris Applet". Tetris Research Page. Archived from the original on December 9, 2006. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^ Heidi Burgiel. How to Lose at Tetris Archived May 13, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, Mathematical Gazette, vol. 81, pp. 194–200 1997

- ^ Demaine, Erik D.; Hohenberger, Susan; Liben-Nowell, David (July 25–28, 2003). Tetris is Hard, Even to Approximate (PDF). Proceedings of the 9th International Computing and Combinatorics Conference (COCOON 2003). Big Sky, Montana. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Lane, Matthew (2017). Power-up: Unlocking the Hidden Mathematics in Video Games. Princeton University Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 9780691161518.

- ^ The Thermodynamics of Tetiris Archived September 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Ars Technica, 2009.

- ^ Barnes, Brian C.; Siderius, Daniel W.; Gelb, Lev D. (2009). "Structure, Thermodynamics, and Solubility in Tetromino Fluids". Langmuir. 25 (12): 6702–6716. doi:10.1021/la900196b. PMID 19397254.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Ackerman, Dan (2016). The Tetris effect: the game that hypnotized the world. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-611-0. OCLC 943694339.

- Brzustowski, John (1992). Can you win at TETRIS? (MSc thesis). University of British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0079748. hdl:2429/3263.

- Ichbiah, Daniel (2009). "IV: Tetris". La saga des jeux vidéo (in French) (Nouvelle ed.). Triel-sur-Seine: Pix'n love éd. pp. 71–85. ISBN 978-2-918272-02-1. OCLC 1194432922.

- Kent, Steven L. (2001). The ultimate history of video games: from Pong to Pokémon and beyond the story behind the craze that touched our lives and changed the world. New York: Three Rivers Press. pp. 377–381. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7. OCLC 47254175.

- Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2009). Vintage games: an insider look at the history of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the most influential games of all time. Amsterdam: Focal Press. pp. 291–301. ISBN 978-0-240-81146-8.

- Plank, Dana (July 25, 2022). "Tetris". In Perron, Bernard; Boudreau, Kelly; Wolf, Mark J.P.; Arsenault, Dominic (eds.). Fifty Key Video Games (First ed.). Routledge. pp. 268–274. doi:10.4324/9781003199205. ISBN 9781003199205.

- Sheff, David; Eddy, Andy (1999). Game Over: Press Start to Continue. Wilton, CT: GamePress. pp. 295–348. ISBN 978-0-966-96170-6. OCLC 1190934258.

- Trefry, Gregory (2010). Casual game design: designing play for the gamer in all of us. Burlington, MA: CRC Press. pp. 179–185. ISBN 978-0-12-374953-6. OCLC 440113525.

Video documentaries

[edit]- Tetris: From Russia with Love at IMDb. Magnus Temple. 2004.

- Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters at IMDb. Adam Cornelius. 2011.

- The Story of Tetris. Gaming Historian. February 2, 2018 – via YouTube.

Further reading

[edit]- Gerasimov, Vadim. "Tetris Story". OverSigma.

- Graham, Sarah (October 29, 2002). "Mathematicians Prove Tetris Is Tough". Scientific American.

- The creation of Tetris. BBC World Service. BBC. December 29, 2012.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- The MS-DOS version of Tetris can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- 1985 in the Soviet Union

- 1985 video games

- Alexey Pajitnov games

- DOS games

- Falling block puzzle games

- Mirrorsoft games

- NP-complete problems

- Puzzle video games

- Russian inventions

- Soviet brands

- Soviet games

- Soviet inventions

- Spectrum HoloByte games

- Tetris

- Tetris games

- Video game franchises introduced in 1985

- Video games developed in the Soviet Union

- World Video Game Hall of Fame