Culhwch and Olwen

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (February 2023) |

| Culhwch ac Olwen | |

|---|---|

| "Culhwch and Olwen" | |

The opening lines of Culhwch and Olwen, from the Red Book of Hergest Kilydd mab Kelydon Wledig a fynnei wraig kyn mwyt ac ef. Sef gwraig a vynna oedd Goleudyd merch Anlawd Wledig. | |

| Author(s) | Anonymous |

| Language | Middle Welsh |

| Date | c. 11th–12th century |

| Series | The Mabinogion |

| Manuscript(s) | White Book of Rhydderch Red Book of Hergest |

| Verse form | Prose |

| Text | Culhwch ac Olwen at Wikisource |

Culhwch and Olwen (Welsh: Culhwch ac Olwen) is a Welsh tale that survives in only two manuscripts about a hero connected with Arthur and his warriors: a complete version in the Red Book of Hergest, c. 1400, and a fragmented version in the White Book of Rhydderch, c. 1325. It is the longest of the surviving Welsh prose tales. Lady Charlotte Guest included this tale among those she collected under the title The Mabinogion.

Synopsis

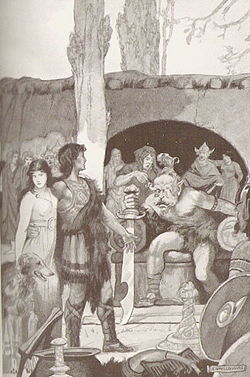

[edit]Culhwch's father, King Cilydd son of Celyddon, loses his wife Goleuddydd after a difficult childbirth.[1] When he remarries, the young Culhwch rejects his stepmother's attempt to pair him with his new stepsister. Offended, the new queen puts a curse on him so that he can marry no one besides the beautiful Olwen, daughter of the giant Ysbaddaden Pencawr. Though he has never seen her, Culhwch becomes infatuated with her, but his father warns him that he will never find her without the aid of his famous cousin Arthur. The young man immediately sets off to seek his kinsman. He finds him at his court in Celliwig in Cornwall.[2][3][4]

Arthur agrees to lend help in whatever capacity Culhwch asks, save the lending of his sword Caledfwlch and other named armaments, or his wife.[a][5] He sends not only six of his finest warriors (Cai, Bedwyr, Gwalchmei, Gwrhyr Gwalstawd Ieithoedd, Menw son of Tairgwaedd, Cynddylig Gyfarwydd), but a huge list of personages of various skills (including Gwynn ap Nudd) recruited to join Culhwch in his search for Olwen.[6] The group meets some relatives of Culhwch's that know Olwen and agree to arrange a meeting. Olwen is receptive to Culhwch's attraction, but she cannot marry him unless her father Ysbaddaden "Chief Giant" agrees, and he, unable to survive past his daughter's wedding, will not consent until Culhwch completes a series of about forty impossible-sounding tasks, including the obtaining of the basket/hamper of Gwyddneu Garanhir,[b] the hunt of Ysgithyrwyn chief boar.[8] The completion of only a few of these tasks is recorded and the giant is killed, leaving Olwen free to marry her lover.

Scholarship

[edit]The prevailing view among scholars was that the present version of the text was composed by the 11th century, making it perhaps the earliest Arthurian tale and one of Wales' earliest extant prose texts,[9] but a 2005 reassessment by linguist Simon Rodway dates it to the latter half of the 12th century.[10] The title is a later invention and does not occur in early manuscripts.[11]

The story is on one level a folktale, belonging to the bridal quest "the giant's daughter" tale type[12] (more formally categorized as Six Go through the Whole World type, AT 513A).[13][14][15] The accompanying motifs (the strange birth, the jealous stepmother, the hero falling in love with a stranger after hearing only her name, helpful animals, impossible tasks) reinforce this typing.[16][12]

However, the bridal quest serves merely as a frame story for the rest of the events that form the in-story,[17] where the title characters go largely unmentioned. The in-story is taken up by two long lists and the adventures of King Arthur and his men. One list is a roster of names, some two hundred of the greatest men, women, dogs, horses and swords in Arthur's kingdom recruited to aid Arthur's kinsman Culhwch in his bridal quest.[c] The other is a list of "difficult tasks" or "marvels" (pl. Welsh: anoethau, anoetheu),[20][14] set upon Culhwch as requirements for his marriage to be approved by the bride's father Ysbaddaden. Included in this list are names taken from Irish legend, hagiography, and sometimes actual history.

The fight against the terrible boar Twrch Trwyth certainly has antecedents in Celtic tradition, namely Arthur's boar-hunt with his hound Cafall, whose footprint is discussed in the Mirabilia appended to the Historia Brittonum.[21] The description of Culhwch riding on his horse is frequently mentioned for its vividness, and features of the Welsh landscape are narrated in ways that are reminiscent of Irish onomastic narratives.[22] As for the passage where Culhwch is received by his uncle, King Arthur, at Celliwig, this is one of the earliest instances in literature or oral tradition of Arthur's court being assigned a specific location and a valuable source of comparison with the court of Camelot or Caerleon as depicted in later Welsh, English, and continental Arthurian legends.[citation needed]

Cultural influence

[edit]Culhwch's horse-ride passage is reused in the 16th-century prose "parody" Araith Wgon, as well as in 17th-century poetic adaptations of that work.[citation needed] The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey has pointed out the similarities between The Tale of Beren and Lúthien, one of the main cycles of J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, and Culhwch and Olwen.[23]

Adaptations

[edit]

- British painter/poet David Jones (1895–1974) wrote a poem called "The Hunt" based on the tale of Culwhch ac Olwen. A fragment of a larger work, "The Hunt" takes place during the pursuit of the boar Twrch Trwyth by Arthur and the various war-bands of Celtic Britain and France.

- In 1988, Gwyn Thomas released a retelling of the story, Culhwch ac Olwen, which was illustrated by Margaret Jones. Culhwch ac Olwen won the annual Tir na n-Og Award for Welsh language nonfiction in 1989.[24]

- A shadow play adaptation of Culhwch and Olwen toured schools in Ceredigion during 2003. The show was created by Jim Williams and was supported by Theatr Felinfach.

- The tale of Culhwch and Olwen was adapted by Derek Webb in Welsh and English as a dramatic recreation for the reopening of Narberth Castle in Pembrokeshire in 2005.[citation needed]

- The Ballad of Sir Dinadan (2003), the fifth book of Gerald Morris's The Squire's Tales series, features an adaptation of Culhwch's quest.

- The Quest (2016) is an artist's book by Shirley Jones focusing on the quest, which is to find the whereabouts of the prisoner, Mabon, son of Modron, in Culhwch and Olwen.[25]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Arthur's other arms being his spear Rhongomyniad, his shield Wynebgwrthucher, and his dagger Carnwennan.

- ^ Which is one of the Thirteen Hallows of Britain.[7]

- ^ More than two hundred fifty names,[18] including two hundred thirty warriors.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Freeman, Philip (2017). Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes. Oxford University Press. pp. 205–6. ISBN 9780190460471. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Guest (1849), pp. 249–257 "Kilhwch and Olwen".

- ^ Ford (1977), pp. 119–121, Ford (2019), pp. 115–117 tr. "Culhwch and Olwen".

- ^ Jones & Jones (1993), pp. 80–83; Jones (2011), unpaginated tr. "Culhwch and Olwen".

- ^ Guest (1849), pp. 257–258; Jones & Jones (1993), p. 84; Ford (2019), p. 119

- ^ Guest (1849), pp. 258–269; Jones & Jones (1993), pp. 84–93; Ford (2019), pp. 119–125

- ^ Guest (1849), pp. 353–355.

- ^ Guest (1849), pp. 280–292; Ford (2019), pp. 130ff

- ^ The Romance of Arthur: An Anthology of Medieval Texts in Translation, ed. James J. Wilhelm. 1994. 25.

- ^ Rodway, Simon, “The date and authorship of Culhwch ac Olwen: a reassessment”, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 49 (Summer, 2005), pp. 21–44

- ^ Davies, Sioned (2004). "Performing Culhwch ac Olwen". Arthurian Literature. 21: 31. ISBN 9781843840282. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ a b Ford (2019) :"At the level of folktale, it belongs to a widely known type, “the giant's daughter.” A number of motifs known to students of the international folktale are clustered here: the jealous stepmother, love for an unknown and unseen maiden, the oldest animals, the helper animals, and the impossible tasks are perhaps the most obvious".

- ^ Owen (1968), p. 29.

- ^ a b Loomis (2015), p. 28.

- ^ Rodway (2019), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Rodway (2019), p. 72: "jealous stepmother"; Loomis (2015), p. 28: ""impossible obstacles, and the hero needs prodigiously endowed helpers".

- ^ Koch (2014), p. 257.

- ^ Dillon, Myles; Chadwick, Nora K. (1967). The Celtic Realms. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 283–285.

- ^ Knight, Stephen Thomas (2015). The Politics of Myth. Berkeley: Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-86844-9.

- ^ Knight & Wiesner-Hanks (1983), p. 13.

- ^ Bromwich & Evans (1992), p. lxvii.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora (1959). "Scéla Muicce Meicc Da Thó". In Dillon, Myles (ed.). Irish Sagas. Radio Éireann Thomas Davis Lectures. Irish Stationery Office. p. 89.: "details of Ailbe's route.. recalls the course taken by the boar Twrch Trwyth in.. Kuhlwch (sic.) and Olwen

- ^ Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle Earth, pp. 193–194: "The hunting of the great wolf recalls the chase of the boar Twrch Trwyth in the Welsh Mabinogion, while the motif of 'the hand in the wolf's mouth' is one of the most famous parts of the Prose Edda, told of Fenris Wolf and the god Tyr; Huan recalls several faithful hounds of legend, Garm, Gelert, Cafall."

- ^ "Tir na n-Og awards Past Winners". Welsh Book Council. cllc.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Jones, Shirley (2016). The Quest. Red Hen Press.

Sources

[edit]This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (March 2020) |

- Bromwich, Rachel; Evans, D. Simon (1992). Culhwch and Olwen: An Edition and Study of the Oldest Arthurian Tale. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1127-X.

- Ford, Patrick K. (1977). Culhwch and Olwen (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03414-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)- —— (2019) [1977]. Culhwch and Olwen (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 113–150. ISBN 978-0-520-30958-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- —— (2019) [1977]. Culhwch and Olwen (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 113–150. ISBN 978-0-520-30958-6.

- Guest, Charlotte (1849). Killhwch and Olwen, or the Twrch Trwyth. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 249–.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- Foster, Idris Llewelyn (1959). Loomis, Roger S. (ed.). Culhwch and Olwen and Rhonabwy's Dream. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-811588-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- Gantz, Jeffrey (1976). Culhwch and Olwen. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044322-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- Jones, Gwyn; Jones, Thomas (1993) [1949], "Culhwch and Olwen", The Mabinogion, Everyman Library, London: J. M. Dent, p. 80-113, ISBN 0-460-87297-4

- Jones, Gwyn (2011) [1949], "Culhwch and Olwen", The Mabinogion, Read Books, ISBN 978-1446546253

- Knight, Stephen; Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (1983). Arthurian Literature and Society. Springer Verlag. pp. 12–19. ISBN 1-349-17302-9.

- Koch, John T. (2014), Lacy, Norris J. (ed.), "The Celtic Lands", Medieval Arthurian Literature: A Guide to Recent Research (revised ed.), Routledge, pp. 256–262, ISBN 978-1-317-65695-1

- Loomis, Richard M. (2015), Lacy, Norris J.; Wilhelm, James J. (eds.), "Culhwch and Olwen", The Romance of Arthur: An Anthology of Medieval Texts in Translation (3 ed.), Routledge, pp. 28–, ISBN 978-1-317-34184-0

- Owen, Douglas David Roy (1968), The Evolution of the Grail Legend, Oxford: University Court of the University of St. Andrews, ISBN 9780050018361

- Rodway, Simon (2019). Lloyd-Morgan, Ceridwen; Poppe, Erich (eds.). Culhwch ac Olwen. University of Wales Press. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-1-786-83344-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)