Kosovo Force

| Kosovo Force | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 11 June 1999 |

| Type | Command |

| Role | NATO peacekeeping |

| Size | 4,302 military personnel[1] |

| Part of | |

| Nickname(s) | "KFOR" |

| Engagements | Yugoslav Wars[2] |

| Website | jfcnaples.nato.int/kfor |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Major general Enrico Barduani, Italian Army |

| Deputy Commander | Brigade-general Cahit İrican,[3] Turkish Armed Forces |

| Chief of Staff | BG John Bozicevic, US Army |

| Command Sergeant Major | Primo luogotenente q.s. Marcello Carlo Pagliara, Italian Army |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

The Kosovo Force (KFOR) is a NATO-led international peacekeeping force and military of Kosovo.[2] KFOR is the third security responder, after the Kosovo Police and the EU Rule of Law (EULEX) mission, respectively, with whom we [who?] work in close coordination.[4] Its operations are gradually reducing until Kosovo's Security Force, established in 2009, becomes self-sufficient.[5]

KFOR entered Kosovo on 12 June 1999,[6] one day after the United Nations Security Council adopted the UNSC Resolution 1244. At the time, Kosovo was facing a grave humanitarian crisis, with military forces from Yugoslavia in action against the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in daily engagements. Nearly one million people had fled Kosovo as refugees by that time, and many permanently did not return.[5]

Currently, 28 states contribute to the KFOR, with a combined strength of approximately 3,800 military personnel.[7]

The mission was initially called Operation Joint Guardian. In 2004, the codename for the mission was changed to Operation Joint Enterprise.

Objectives

[edit]

KFOR focuses on building a secure environment and guaranteeing the freedom of movement through all Kosovo territory for all citizens, irrespective of their ethnic origins, in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1244.[5]

The Contact Group countries have said publicly that KFOR will remain in Kosovo to provide the security necessary to support the final settlement of Kosovo authorities.[8]

Structure

[edit]

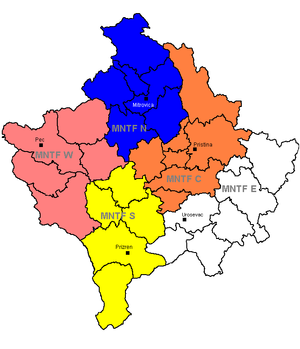

KFOR contingents were grouped into five multinational brigades and a lead nation designated for each multinational brigade.[9] All national contingents pursued the same objective to maintain a secure environment in Kosovo.

In August 2005, the North Atlantic Council decided to restructure KFOR, replacing the five existing multinational brigades with five task forces, to allow for greater flexibility with, removing restrictions on the cross-boundary movement of units based in different sectors of Kosovo.[8] Then in February 2010, the Multinational Task Forces became Multinational Battle Groups, and in March 2011, KFOR was restructured again, into just two multinational battlegroups; one based at Camp Bondsteel, and one based at Peja.[10]

In August 2019, the KFOR structure was streamlined. Under the new structure, the former Multinational Battlegroups are reflagged as Regional Commands, with Regional Command-East (RC-E) based at Camp Bondsteel, and Regional Command-West (RC-W) based at Camp Villaggio Italia.

Structure 2023

[edit]- Kosovo Force, at Camp Film City, Pristina[11]

- Headquarters Support Group (HSG), at Camp Film City;

- Joint Logistics Support Group (JLSG), in Pristina (Logistics and engineering support)

- Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance Battalion (ISRBN), at Camp Film City

- Regional Command-East (RC-E), at Camp Bondsteel near Ferizaj (U.S. Army force supported by Greece, Italy, Finland, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, Switzerland and Turkey)

- Regional Command-West (RC-W), at Camp Villaggio Italia near Peja (Italian Army force supported by Austria, Croatia, Moldova, North Macedonia, Poland, Slovenia, Switzerland and Turkey)

- Multinational Specialized Unit (MSU), in Pristina (Military Police, crowd and riot control, peacekeeping operations regiment composed entirely of Italian Carabinieri)

- KFOR Tactical Reserve Battalion (KTRBN), at Camp Novo Selo (composed entirely of Hungarian Army troops)

- Kosovo Force Office, at Skopje International Airport

Contributing states

[edit]

At its height, KFOR troops consisted of 50,000 men and women coming from 39 different NATO and non-NATO nations. The official KFOR website indicated that in 2008 a total 14,000 soldiers from 34 countries were participating in KFOR.[12] The following list shows the number of troops which have participated in the KFOR mission. Most of the force has been downsized since 2008; current numbers are reflected here as well:[13][14]

| Active[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Membership | Strength | ||

| NATO | EU | |||

| Yes | No | 90 | ||

| No | No | 57 | ||

| No | Yes | 107 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 300[16] | ||

| Yes | No | 5 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 150 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 35 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 35 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 70 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 3 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 300 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 121 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 365 | ||

| No | Yes | 13 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 855 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 140 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 1 | ||

| No | No | 44 | ||

| Yes | No | 2 | ||

| Yes | No | 68 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 247 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 184 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 105 | ||

| Yes | Yes | 3 | ||

| No | No | 211 | ||

| Yes | No | 325 | ||

| Yes | No | 41 | ||

| Yes | No | 598 | ||

| 28 | 23 | 18 | 4,302 | |

| Withdrawn | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Membership | Year of withdrawal | ||

| NATO | EU | |||

| No | No | 2006[17] | ||

| No | No | 2008[18][19] | ||

| Yes | Yes | 2010[20] | ||

| Yes | Yes | 2018[21] | ||

| No | No | 2008[22] | ||

| No | No | 2014[23] | ||

| Yes | Yes | 2017[24] | ||

| Yes | No | 2020[25] | ||

| Yes | Yes | 2016[26] | ||

| Yes | Yes | 2021[27][28] | ||

| No | No | 2003[29] | ||

| Yes | Yes | 2009[30] | ||

| Yes | Yes | 2010[31] | ||

| No | No | 2022[32] | ||

| No | No | 2001[33] | ||

KFOR commanders

[edit]- Sir Michael Jackson (United Kingdom, 10 June 1999 – 8 October 1999)

- Klaus Reinhardt (Germany, 8 October 1999 – 18 April 2000)

- Juan Ortuño Such (Spain, 18 April 2000 – 16 October 2000)

- Thorstein Skiaker (Norway, 6 April 2001 – 3 October 2001)

- Marcel Valentin (France, 3 October 2001 – 4 October 2002)

- Fabio Mini (Italy, 4 October 2002 – 3 October 2003)

- Holger Kammerhoff (Germany, 3 October 2003 – 1 September 2004)

- Yves de Kermabon (France, 1 September 2004 – 1 September 2005)

- Giuseppe Valotto (Italy, 1 September 2005 – 1 September 2006)

- Roland Kather (Germany, 1 September 2006 – 31 August 2007)

- Xavier de Marnhac (France, 31 August 2007 – 29 August 2008)

- Giuseppe Emilio Gay (Italy, 29 August 2008 – 8 September 2009)

- Markus J. Bentler (Germany, 8 September 2009 – 1 September 2010)

- Erhard Bühler (Germany, 1 September 2010 – 9 September 2011)

- Erhard Drews (Germany, 9 September 2011 – 7 September 2012)

- Volker Halbauer (Germany, 7 September 2012 – 6 September 2013)

- Salvatore Farina (Italy, 6 September 2013 – 3 September 2014)

- Francesco Paolo Figliuolo (Italy, 3 September 2014 – 7 August 2015)

- Guglielmo Luigi Miglietta (Italy, 7 August 2015 – 1 September 2016)

- Giovanni Fungo (Italy, 1 September 2016 – 15 November 2017)

- Salvatore Cuoci (Italy, 15 November 2017 – 28 November 2018)

- Lorenzo D'Addario (Italy, 28 November 2018 – 19 November 2019)

- Michele Risi (Italy, 19 November 2019 – 13 November 2020 )

- Franco Federici (Italy, 13 November 2020 – 15 October 2021)

- Ferenc Kajári (Hungary, 15 October 2021 – 14 October 2022 )

- Angelo Michele Ristuccia (Italy, 14 October 2022 – 10 October 2023 )

- Özkan Ulutaş (Turkey, 10 October 2023 – 10 October 2024)

- Enrico Barduani (Italy, 11 October 2024 – present)

Note: The terms of service are based on the official list of the KFOR commanders[34] and another article.[35]

Kosovo peacekeeping

[edit]

Events

[edit]On 9 June 1999 the Military Technical Agreement or Kumanovo Agreement between KFOR and the Governments of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Serbia was signed by NATO General Sir Mike Jackson and Yugoslavia Colonel General Svetozar Marjanovic concluding the Kosovo War. This agreement outlined a rapid withdrawal of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Forces from Kosovo, assigning to the KFOR Commander the airspace control over Kosovo and pending the later United Nations Security Council Resolution's approval, the deployment of KFOR to Kosovo.[36] On 10 June 1999 the United Nations Security Council adopted the UNSC Resolution 1244 authorizing the deployment in Kosovo of an international civil and security presence for an initial period of 12 months, and to continue thereafter unless the UNSC decides otherwise. The civil presence was represented by the United Nations Mission In Kosovo (UNMIK), while the security presence was led by KFOR.[37]

Following the adoption of UNSCR 1244, General Jackson, acting on the instructions of the North Atlantic Council, made immediate preparations for the rapid deployment of the security force (Operation Joint Guardian), mandated by the United Nations Security Council. The first NATO-led elements entered Kosovo at 5 a.m. on 12 June. On 21 June, the UCK undertaking of demilitarization and transformation was signed by COMKFOR and the Commander in Chief of the UCK (Mr. Hashim Thaci), moving KFOR into a new phase of enforcing the peace and supporting the implementation of a civil administration under the auspices of the United Nations.[9]

Within three weeks of KFOR entry, more than half a million out of those who had left during the bombing were back in Kosovo. However, in the months following KFOR deployment, approximately 150,000 Serbs, Romani and other non-Albanians fled Kosovo while many of the remaining civilians were subjected to violence and intimidation from ethnic Albanians.[38]

October 28, 2000 the first Municipal Assembly Elections were held. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe(OSCE) announced that approximately 80% of the population participated in this vote for local representatives. The final results were certified by the Special Representative for Kosovo of the UN Secretary-General, Bernard Kouchner, on 7 November.[39]

KFOR was initially composed of 40,000 troops from NATO countries. Troop levels were reduced to 26,000 by June 2003, then to 17,500 by the end that year. Combat troops were reduced more than support troops. KFOR tried to deal with this by transferring tasks to UNMIK and the Kosovo Police Service (KPS), but UNMIK was also reducing its number of international police, and KPS were not numerous enough or competent enough to take over from KFOR.

The 2004 unrest in Kosovo was the worst ethnic violence since 1999, leaving hundreds wounded and at least 14 people dead. On 17 and 18 March 2004, a wave of violent riots swept through Kosovo, triggered by two incidents perceived as ethnically motivated acts. The first incident, on 15 March 2004, an 18-year-old Serb was shot near the all Serb village of Čaglavica, near Pristina.[40][41] On 16 March, three Albanian children drowned in the Ibar River in the village of Čabar, near the Serb community of Zubin Potok. A fourth boy survived. It was speculated that he and his friends had been chased into the river by Serbs in revenge for the shooting of Ivić the previous day, but this claim has not been proven.[42] According to Human Rights Watch, the violence in March 2004 left 19 dead, 954 wounded, 550 homes destroyed, twenty-seven Orthodox churches and monasteries burned, and leaving approximately 4,100 Serbs, Roma, Ashkali (Albanian-speaking Roma), and other non-Albanian minorities displaced. Nineteen people, eight Kosovo Serbs and eleven Kosovo Albanians, were killed and over a thousand wounded-including more than 120 KFOR soldiers and UNMIK police officers, and fifty-eight Kosovo Police Service (KPS) officers.[43]

The 10 February 2007 protest in Kosovo resulted in 2 deaths and many injuries. A crowd of ethnic Albanians in Pristina protested against a UN plan, also known as the Ahtisaari Plan, they felt fell short of granting full independence for Kosovo. The proposals, unveiled 2 February, recommended a form of self-rule and was strongly opposed by Serbia. The UN Security Council did not endorse the plan.[44][45]

On February 17, 2008 unrest followed Kosovo's declaration of independence . Some Kosovo Serbs opposed to secession boycotted the move by refusing to follow orders from the central government in Pristina and attempted to seize infrastructure and border posts in Serb-populated regions. There were also sporadic instances of violence against international institutions and governmental institutions, predominantly in North Kosovo. After declaring independence, the Kosovo government introduced new customs stamps, a symbol of their newly declared sovereignty. Serbia refused to recognize the customs stamps which led to the de facto prohibition of both direct import of goods from Kosovo to Serbia, as well as transit to third countries. Goods from Serbia, however, could still be freely imported into Kosovo.[46][47] Pursuant to the Statement by the President of the Security Council on 26 November 2008 (S/PRST/2008/44), UNMIK was restructured and its rule of law executive tasks were transferred to EULEX. EULEX maintains a limited residual capability as a second security responder and provides continued support to Kosovo Police's crowd and riot control capability.[48][47]

The 25 August 2009 Pristina protests resulted in vehicle damages and multiple injuries.

On 22 July 2010, the International Court of Justice delivered its advisory opinion on Kosovo's declaration of independence declaring that "the adoption of the declaration of independence of the 17 February 2008 did not violate general international law because international law contains no 'prohibition on declarations of independence'," nor did the adoption of the declaration of independence violate UN Security Council Resolution 1244, since this did not describe Kosovo's final status, nor had the Security Council reserved for itself the decision on final status.

20 July 2011 Kosovo banned all imports from Serbia and introduced 10 percent tax for imports from Bosnia as both countries blocked exports from Kosovo.[49] On 26 July 2011, a series of confrontations in North Kosovo began with a Kosovo Police operation to seize two border outposts along the Kosovo Serbia border and consequent clashes continued until 23 November. The clashes, resulting in multiple deaths and injuries, were over differences between who would administer the border crossings between Kosovo and Serbia along with what would happen with the revenue collected from the customs and removal of roadblocks to secure freedom of movement. On 3 September 2011, a deal to unblock the impasse between Serbia and Kosovo over exports was struck at EU-led negotiations in Brussels. Serbia agreed to accept goods marked “Kosovo Customs”, while Pristina gave up including state emblems, coats of arms, flags, or use of the word “republic” allowing Kosovo to interpret the label as referring to the customs of independent Kosovo, whereas Serbia could see it as a provincial customs label.[50]

On 14 and 15 February 2012, an advisory referendum on accepting the institutions of the Republic of Kosovo was held in North Kosovo. 1 June 2012 Kosovo Serbs and a KFOR soldier were wounded when peacekeepers tried to dismantle Serb barricades, among the last on major roads yet to be dismantled, blocking traffic.[51]

On 8 February 2013, a series of protests began against increases in electricity bills which later turned into protests against corruption. On 19 April 2013, the Belgrade Pristina Normalization Agreement was signed between the governments of Kosovo and Serbia. Prior, North Kosovo functioned independently from the institutions in Kosovo by refusing to recognize Kosovo's 2008 declaration of independence and the Government of Kosovo opposed any parallel government for Serbs.[52][53][54] The Brussels Agreement abolished the parallel structures and both governments agreed upon creating a Community of Serb Municipalities. The association was expected to be officially formed in 2016 but continued discussions has resulted in not forming the Community. By signing the Agreement, the European Union's Commission considered Serbia had met key steps in its relations with Kosovo and recommended that negotiations for accession of Serbia to the European Union be opened.[55] Several days after the agreement was reached, the European Commission recommended authorizing the launch of negotiations between the EU and Kosovo on the Stabilisation and Association Process.[56]

The 2014 student protest in Kosovo demanded the resignation or dismissal of the University of Pristina Rector. Students threw red paint and rocks at the Kosovo Police who responded with tear gas. 30 Kosovo Police officers were injured and more than 30 students were arrested.[57] The upper airspace over Kosovo, skies over 10,000 feet, was re-opened for civilian traffic overflights on 3 April 2014. This followed a decision by the North Atlantic Council to accept the offer by the Government of Hungary to act as a technical enabler through its national air navigation service provider, Hungarocontrol.[58]

The 2015 Kosovo protests were a series of violent protests calling for the resignation of a Minister and the passage of a bill on Trepca Mines ownership. On 6 January protestors claiming that among the pilgrims visiting a local church for Orthodox Christmas included displaced Serbs from Gjakova involved in war crimes against Albanians in 1998-1999 threw blocks of ice at the bus breaking one of its windows. Kosovo Police arrested two protestors. The Minister For Community and Return, who accompanied the pilgrims, made a statement that was perceived by Kosovo Albanians as an ethnic slur leading to riots. The rioters, which included students and opposition parties, demanded his resignation and he was dismissed by the Kosovo Prime Minister.[59] The Kosovo government's announcement it was postponing a decision on the privatization process of the Trepca mining complex after Serb Kosovo Parliamentary Representatives protested claiming that the Serbian government had the right to retain ownership was met with student-led protests in Pristina, Lipljan and Ferizaj/Urosevac, Kosovo Albanian Miners in South Trepca and Kosovo Serbian Miners in North Trepca. Trepca's lead, zinc, and silver mines once accounted for 75 percent of the mineral wealth of socialist Yugoslavia, employing 20,000 people. Trepca now operates at a minimum level to keep the mines alive employing several thousand miners. The Trepca mines are under the oversight of the Kosovo Privatization Agency.[60]

9 January 2016, thousands of protestors wanted the government to withdraw from a border demarcation agreement with Montenegro and an agreement to set up a Community of Serb Municipalities. Police fired tear gas responding to protesters who threw Molotov cocktails and set fire to a government building. The Kosovo Assembly later withdrew the agreements.[61]

On 14 January 2017, the Belgrade-Kosovska Mitrovica train incident happened when rhetoric was exchanged between Kosovo and Serbian Officials after Serbia announced restarting train service between Kosovo and Serbia and Kosovo responded stating that the train would be stopped at the border. The initial train was painted in the colors of the Serbian flag with the words “Kosovo is Serbia” printed down the side which was considered provocative by Kosovo Officials and Kosovo Officials stated that Police would stop it at the border. The train traveled from Belgrade to the border town of Raska and returned never crossing into Kosovo.[62] Train service between Kosovo and Serbia remains non-existent.

On 21 March 2018, Kosovo's Assembly ratified the border agreement with Montenegro. The European Union set ratification as a condition before it would grant Kosovo nationals visa-free access to the pass-port free Schengen area.[63] 8 September, Serbia's president visited North Kosovo's Gazivode Lake, an important source of Kosovo's water. The following day, his planned visit to the majority-Serb village Banje was cancelled by the Kosovo government after Kosovo Albanian protestors put up barricades at the village's entrance.[64] 29 Sept, Kosovo's president visited Gazivode Lake. Serbia accused Kosovo police of seizing control of the lake and briefly detaining workers and Kosovo said police were there to provide security for the visit and nobody was detained. A Kosovo Serbian representative said Serbia was putting its military as well as police under high alert as a result.[65] 20 November The international police agency (INTERPOL), rejected Kosovo's membership.[66] On 21 November, Kosovo imposed an import tax on Serbian and Bosnia Herzogovina goods. Kosovo said the tariff would be lifted when Serbia recognizes its sovereignty and stops blocking it from joining international organizations and Serbia said it will not participate in further dialogue until the measure is lifted.[67]

On 29 September 2023, the NATO Secretary-General announced the authorisation of additional forces to address the build up of Serbian troops on the border of Kosovo and Serbia in order to keep peace within the region.[68]

KFOR fatalities

[edit]

Since the KFOR entered Kosovo in June 1999, soldiers from Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Morocco, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States were killed in the line of duty.[69][failed verification]

The biggest fatal event is that of the 42 Slovak soldiers dead in a 2006 military plane crash in Hungary.[70][71] In 20 years, more than 200 NATO soldiers have died as part of KFOR.[72] On 1 July 2021, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg confirmed that the KFOR mission will continue.[73] On 29 May 2023, more than 30 NATO peacekeeping soldiers defending three town halls in northern Kosovo have been injured in clashes with Serb protesters, while Serbia's president put the army on the highest level of combat alert.[74] The tense situation developed after ethnic Albanian mayors took office in northern Kosovo's Serb-majority area after elections that the Serbs boycotted.

Notes and references

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Contributing Nations". jfcnaples.nato.int. NATO (Official website). Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ a b Khakee, Anna; Florquin, Nicolas (1 June 2003). "Kosovo: Difficult Past, Unclear Future" (PDF). Kosovo and the Gun: A Baseline Assessment of Small Arms and Light Weapons in Kosovo. 10. Pristina, United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo and Geneva, Switzerland: Small Arms Survey: 4–6. JSTOR resrep10739.9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

Kosovo—while still formally part of the so-called State Union of Serbia and Montenegro dominated by Serbia—has, since the war, been a United Nations protectorate under the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). [...] However, members of the Kosovo Serb minority of the territory (circa 6–7 per cent in 2000) have, for the most part, not been able to return to their homes. For security reasons, the remaining Kosovo Serb enclaves are, in part, isolated from the rest of Kosovo and protected by the multinational NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR).

- ^ "NATO'nun Kosova'daki Barış Gücü'nün Komutan Yardımcısı Tuğgeneral Cahit İrican oldu". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "KFOR'S STRATEGIC RESERVE FORCE TO REDEPLOY FROM KOSOVO FOLLOWING SUCCESSFUL 45-DAY MISSION". jfcnaples.nato.int/. 28 October 2024. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c "NATO's role in Kosovo". nato.int. 29 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "NATO's role in Kosovo". nato.int. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "NATO Mission in Kosovo (KFOR)". shape.nato.int. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ a b "NATO Topics: Kosovo Force (KFOR) – How did it evolve?". Nato.int. 20 February 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ a b Wentz, Larry (July 2002). "Lessons from Kosovo: The KFOR Experience".

- ^ Muhamet Brajshori (29 December 2010). "US troops to guard Kosovo's border". setimes.com. Southeast European Times. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ "Units". Kosovo Force. NATO. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "KFOR Press Release". Nato.int. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Kosovo Force (KFOR)" (PDF). NATO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "20130422_130419-kfor-placemat" (PDF). Nato.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "Contributing Nations". NATO. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Bulgaria sends 100-strong contingent to KFOR in Kosovo". nova.bg (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20090324234723/http://www.jgm.gov.ar/Paginas/MemoriaDetallada05/04_Ministerio_Defensa/04_Ministerio_Defensa.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Azerbaijani troops part of the KFOR family". www.nato.int. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ NATO. "Relations with Azerbaijan". NATO. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Belgian mission in Kosovo winds down". vrt.be. 31 October 2023. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ "Estonian Defence Forces conclude participation in NATO-led Kosovo mission". ERR.ee. 2 November 2018. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Georgia Withdraws Troops from Kosovo". Civil.ge. Tbilisi. 15 April 2008. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "After 14 years Moroccan contingent leaves KFOR". JFC Naples. 18 January 2014. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "KFOR marks the end of Netherlands' contribution to the mission". Pristina: JFC Naples. 24 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Oppdraget som endret Forsvaret". Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Luxembourg to withdraw military presence in Kosovo". Luxembourg Times. 10 May 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Bósnia e Herzegovina 1996, ponto de viragem no Exército Português". Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Portuguese military contingent departs for Kosovo". Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Russian troops leave KFOR". NATO. 2 July 2003. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Spain to withdraw Kosovo troops". BBC News. 23 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Slovak troops will leave Kosovo". The Slovak Spectator. 4 October 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Ukraine is withdrawing peacekeepers from Kosovo". Ministry of Defense (Ukraine). 22 August 2022. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ The National (28 July 2019). "Special Report:The Day Emirati Troops came to help war torn Kosovo". Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "KFOR Commanders". SHAPE. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Nato's role in Kosovo". NATO. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ NATO (9 June 1999). "Military Technical Agreement between the International Security Force ("KFOR") and the Governments of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Serbia". Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ "RESOLUTION 1244 (1999)". undocs.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Abrahams, Fred (2001). Under Orders: War Crimes in Kosovo. Human Rights Watch. pp. 454–456. ISBN 9781564322647. Archived from the original on 26 August 2024. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Kosovo municipal election results". Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ King, Iain; Garon, Sheldon; Mason, Whit (2006). Peace at Any Price: How the World Failed Kosovo. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801445396. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "The Failure to Protect". undocs.org. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "No evidence over Kosovo drownings". BBC. 28 April 2004. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ "Anti-Minority Violence in Kosovo, March 2004". HumanRightsWatch. 25 July 2004. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ "Two dead following Kosovo clashes". Archived from the original on 26 August 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ "Kosovo's path to independence". Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ "Kosovo and Serbia battle over customs stamps".

- ^ a b "About EULEX". Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Rule of law in Kosovo and the Mandate of UNMIK". Archived from the original on 26 August 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Kosovo bans Serbian imports, taxes Bosnian goods". Reuters. 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Kosovo, Serbia Reach Customs Deal". 3 September 2011.

- ^ "Kosovo Serbs and NATO troops clash in tense north". Reuters. 1 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ BBC, Could Balkan break-up continue? Archived 29 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 22.02.08

- ^ ""Koha ditore": Kosovska vlada bez ingerencija na severu Kosova - Vesti dana - Vesti Krstarice". 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ Kosovo PM: End to Parallel Structures Archived 14 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BalkanInsight.com, March 7, 2008

- ^ "EU Commission recommends start of Serbia membership talks". Reuters. 22 April 2013. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "Recommendation for a COUNCIL DECISION authorising the opening of negotiations on a Stabilisation and Association Agreement between the European Union and Kosovo" (PDF). European Commission. 22 April 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Police clash with students in Kosovo, dozens reported injured". Reuters. 7 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ "NATO re-opens the upper airspace over Kosovo for civilian air traffic overflights". 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "In Kosovo, a Fear of 'The Other' is allowing 'our own' to get away with internal damage to the state". K2.0. 28 October 2016. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Delays Over Trepca Ignite Protests in Kosovo". 20 January 2015. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "Large anti-government protest in Kosovo turns violent". 2016 Zululand Observer. 9 January 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Kosovo accused of 'provoking war' after stopping Serbian train at border". The Independent. 15 January 2017. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Kosovo Parliament Approves Montenegro Border Deal". 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ "Kosovo-Serbia Deal 'Not Even Close', Vucic Says". 10 September 2018.

- ^ "Kosovo president visits disputed area after similar visit by Serbian leader". Reuters. 29 September 2018. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "Kosovo Fails For Third Time To Win Interpol Membership". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 November 2018. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "European Parliament Urges Kosovo To Drop 100 Percent Tariff On Serbian Goods". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "Secretary General statement on the situation in Kosovo". 29 September 2023. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ "Bundesheer - TRUPPENDIENST International - Edition 2/2010 - The Austrian Armed Forces in Kosovo". www.bundesheer.at. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "42 Dead In Military Plane Crash In Hungary". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 8 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Slovak military plane crashes in Hungary killing 42". The New York Times. 20 January 2006. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "KFOR in Kosovo - 20 years later". European Western Balkans. 12 June 2019. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Loxha, Amra Zejneli (July 2021). "NATO's Stoltenberg Tells Kosovo That KFOR Mission Is There To Stay". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "NATO Troops Injured in Clashes with Serb Protesters in Kosovo". The Guardian. 30 May 2023. Archived from the original on 26 August 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

External links

[edit]- KFOR Placemap

- KFOR official site (NATO)

- K-For: The task ahead (from BBC News, 13 June 1999)

- First deaths in K-For operation (from BBC News, 14 June 1999)

- Memorial honors soldiers' sacrifices June 2002: 68 soldiers have died since KFOR entered Kosovo.

- Radio KFOR

- Kosovo War

- NATO-led peacekeeping in the former Yugoslavia

- United States Marine Corps in the 20th century

- Military units and formations established in 1999

- 1999 establishments in Serbia

- 1999 establishments in Kosovo

- Military of Kosovo

- Military operations involving India

- Military operations involving Portugal