Koper

Koper

Capodistria | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Koper from above | |

| Coordinates: 45°33′N 13°44′E / 45.550°N 13.733°E | |

| Country | |

| Traditional region | Slovene Littoral |

| Statistical region | Coastal-Karst |

| Region | Slovene Istria |

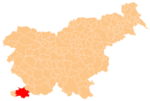

| Municipality | City Municipality of Koper |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Aleš Bržan (LAB) |

| Area | |

• Total | 13.0 km2 (5.0 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

• Total | 25,753 |

| • Rank | 5th |

| • Density | 2,000/km2 (5,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 6000 |

| Area code | +386 (0)5 |

| Vehicle registration | KP |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Website | www |

| [1] | |

Koper (Slovene: [ˈkòːpəɾ] ; Italian: Capodistria) is the fifth-largest city in Slovenia. Located in the Istrian region in the southwestern part of the country, Koper is the main urban center of the Slovene coast. Port of Koper is the country's only container port and a major contributor to the economy of the Municipality of Koper. The city is a destination for a number of Mediterranean cruising lines.

Koper is also one of the main road entry points into Slovenia from Italy, which lies to the north of the municipality. The main motorway crossing is at Spodnje Škofije to the north of the city of Koper. The motorway continues into Rabuiese and Trieste. Koper also has a rail connection with the capital city, Ljubljana. On the coast, there is a crossing at Lazaret into Lazzaretto in Muggia municipality in Trieste province. The Italian border crossing is known as San Bartolomeo.

Sights

[edit]Major sights in Koper include the 15th-century Praetorian Palace and Loggia in Venetian Gothic style, the 12th-century Carmine Rotunda church, and St. Nazarius' Cathedral, with its 14th-century tower.

Names

[edit]The Italian name of the city was anciently written as Capo d'Istria,[2] and is reported on maps and sources in other European languages as such. Ancient names of the city include Ægidia and Justinopolis.[3] Modern names of the city include Croatian: Kopar, Serbian: Копар, romanized: Kopar, and German: Gafers. The Slovene-speaking population calls the city Koper. The Slavic-speaking population, present in the area since at least the late 7th century,[4] largely relied on oral tradition up to the invention of printing. The Slovenian name Koper was first attested in writing in 1557, but with the spelling Copper.[5]

History

[edit]

Koper began as a settlement built on an island in the southeastern part of the Gulf of Koper in the northern Adriatic. Called Insula Caprea (Goat Island) or Capro by Roman settlers, it developed into the city of Aegida,[2] which was mentioned by the Roman author Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia (Natural History) (iii. 19. s. 23).[6]

In 568, Roman citizens of nearby Tergeste (modern Trieste) fled to Aegida due to an invasion of the Lombards. In honour of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian II, the town was renamed Justinopolis.[2] Later, Justinopolis was under both Lombard and Frankish rule and was briefly occupied by Avars in the 8th century.

Since at least the 8th century (and possibly as early as the 6th century) Koper was the seat of a diocese. One of Koper's bishops was the Lutheran reformer Pier Paolo Vergerio. In 1828, it was merged into the Diocese of Trieste.

Trade between Koper and Venice has been recorded since 932. In the war between Venice and the Holy Roman Empire, Koper was on the latter side, and as a result was awarded with town rights, granted in 1035 by Emperor Conrad II. After 1232, Koper was under the Patriarch of Aquileia, and in 1278 it joined the Republic of Venice. It was at this time that the city walls and towers were partly demolished.[7]

In 1420, the Patriarch of Aquileia ceded his remaining possessions in Istria to the Republic, consolidating Venetian power in Koper.[8]

Koper grew to become the capital of Venetian Istria and was renamed Caput Histriae 'head of Istria' (from which stems its modern Italian name, Capodistria).

The 16th century saw the population of Koper fall drastically, from its high of between 10,000 and 12,000 inhabitants, due to repeated plague epidemics.[9] When Trieste became a free port in 1719, Koper lost its monopoly on trade, and its importance diminished further.[10]

According to the 1900 census, 7,205 Italian, 391 Slovenian, 167 Croatian, and 67 German inhabitants lived in Koper.

Assigned to Italy from Austria-Hungary after World War I, at the end of World War II it was part of the Zone B of the Free Territory of Trieste, controlled by Yugoslavia. Most of the Italian inhabitants left the city by 1954, when the Free Territory of Trieste formally ceased to exist and Zone B became part of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1977, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Koper was separated from the Diocese of Trieste.

With Slovenian independence in 1991, Koper became the only commercial port in Slovenia. The University of Primorska is based in the city.

The influence of the Port of Koper on tourism was one of the factors in Ankaran deciding to leave the municipality in a referendum in 2011 to establish its own municipality.

Architecture

[edit]

Koper's 15th-century Praetorian Palace is located on the city square. It was built from two older 13th-century houses that were connected by a loggia, rebuilt many times, and then finished as a Venetian Gothic palace. Today, it is home to the city of Koper's tourist office.[11]

The city's Cathedral of the Assumption was built in the second half of the 12th century and has one of the oldest bells in Slovenia (from 1333), cast by Nicolò and Martino, the sons of Master Giacomo of Venice.[12][13] The upper terrace is periodically open and offers a great view of the Bay of Trieste. In the middle of it hangs the Sacra Conversatione painting from 1516, one of the best Renaissance paintings in Slovenia, made by Vittore Carpaccio.[14]

Climate

[edit]Koper has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa). There is a substantial amount of rainfall in Koper, even in the driest month, with each month averaging well over 60 mm (2.4 in). This climate is considered to be Cfa according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. The average temperature in Koper is 14.4 °C (57.9 °F). The average annual rainfall is 988 millimetres (39 in).

| Climate data for Koper (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1950–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.0 (64.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.3 (84.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.8 (101.8) |

33.5 (92.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

24.9 (76.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

38.8 (101.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

27.3 (81.1) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.8 (14.4) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

0.4 (32.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51 (2.0) |

58 (2.3) |

54 (2.1) |

63 (2.5) |

82 (3.2) |

91 (3.6) |

72 (2.8) |

71 (2.8) |

124 (4.9) |

121 (4.8) |

118 (4.6) |

84 (3.3) |

988 (38.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 121 |

| Source: Slovenian Environment Agency[15] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

In the past, Italian was the most common language spoken in the town, but its presence decreased sharply after Slovenian Istria was incorporated into Yugoslavia in 1954, with most of the ethnic Italians leaving the town.

Today, Koper is officially bilingual, with both Slovene and Italian as its official languages, with Italian being mainly used as a secondary language by the Slovene-speaking majority. Slovene dominates with virtually all citizens speaking it, followed by pockets of speakers of Italian and Croatian.

Sports

[edit]The main association football club is FC Koper, who currently play in the Slovenian PrvaLiga, the top flight of Slovenian football, having won it once.

Port

[edit]

First established during the Roman Empire, the Port of Koper has played an important role in the development of the area. It is among the largest in the region and is one of the most important transit routes for goods heading from Asia to central Europe. In contrast with other European ports, which are managed by port authorities, the activities of the Port of Koper comprise the management of the free zone area, the management of the port area, and the role of terminal operator.

Prominent citizens

[edit]- Gian Rinaldo Carli (1720–1795), man of letters

- Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1460 – c. 1525), painter. Born in Venice, lived in Koper (then Capodistria)

- Vittorio Italico Zupelli (1859–1945), Italian general and minister

- Vlatko Čančar (born 1997), professional basketball player

- Lucija Čok (born 1941), linguist, politician

- Zlatko Dedić (born 1984), football player

- Domenico da Capodistria (born late 14th century), architect

- Lorella Flego (born 1974), TV entertainer

- Enej Jelenič (born 1992), footballer

- Ioannis Kapodistrias (1776–1831), Greek patriot and first governor of the Greek state (1828–1831) his family hailed originally from Koper/Capodistria

- Andreja Klepač (born 1986), professional tennis player

- Tinkara Kovač (born 1978), singer

- Matjaž Markič (born 1983), swimmer

- Dragan Marušič (born 1953), former rector of the University of Primorska

- Davor Mizerit (born 1981), rower

- Igor Pribac (born 1958), philosopher

- Pier Antonio Quarantotti Gambini (1910–1965), journalist and writer. Born in Pazin (then Pisino), lived in Koper (then Capodistria)[16][17]

- Mladen Rudonja (born 1971), football player

- Tomaž Šalamun (1941–2014), poet

- Santorio Santorio (1561–1636), medical scientist

- Nazario Sauro (1880–1916), Italian irredentist and sailor

- Spartaco Schergat (1920–1996), military frogman, caused damage to the British battleship Queen Elizabeth in 1941. Italian gold medal in the Second World War[18]

- Damir Skomina (born 1976), football referee

- Francesco Trevisani (1656–1746), painter

- Pier Paolo Vergerio the Elder (1370–1444/1445), humanist, statesman and canonist[19]

- Pier Paolo Vergerio the Younger (1498–1565), man of the Church

- Gašper Vinčec (born 1981), professional Finn Class Sailor

- Bruno Zago, footballer (born 1919)

- Vittorio Italico Zupelli (1859–1945), general, minister

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] Buzet, Croatia

Buzet, Croatia Ferrara, Italy

Ferrara, Italy Jiujiang, China

Jiujiang, China Muggia, Italy

Muggia, Italy San Dorligo della Valle, Italy

San Dorligo della Valle, Italy Žilina, Slovakia

Žilina, Slovakia

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Koper". Prebivalstvo - izbrani kazalniki, naselja, Slovenija, letno. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b c John Everett-Heath (13 September 2018). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. OUP Oxford. p. 989. ISBN 978-0-19-256243-2.

- ^ Hopkins, Daniel J. (2001). Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary, vol. 10. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. p. 604.

- ^ "Storia di Capodistria". City of Koper. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Golec, Boris (2015). "Najzgodnejše omembe Istre, Trsta in Primorja v slovenskih besedilih" (PDF). Acta Histriae. 23 (4): 678. ISSN 1318-0185. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Jeffrey Henderson (ed.). Natural History. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "A Historical Outline of Istria". Zrs-kp.si. Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Schutte, Anne Jacobson: Pier Paolo Vergerio: the making of an Italian reformer; p23. Books.google.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ Schutte, Anne Jacobson; p24. Books.google.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "History of Koper – Lonely Planet Travel Information". Lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Praetorian Palace, Koper, The Official Travel Guide". Slovenian Tourist Board. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Semi, Francesco (1933). "Il duomo di Capodistria". Atti e memorie della Società istriana di archeologia e storia patria. 45. Pula: 169.

- ^ Ranieri, Mario Cossar (1929). "Lungo le coste Adriatiche: Giustinopoli, gemma de l'Istria". Le vie d'Italia e dell'America latina. 35 (1). Milan: 88. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Cathedral of the Assumption, Koper, The Official Travel Guide". Slovenian Tourist Board. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "Koper Podnebne statistike 1950-2020" (in Slovenian). Slovenian Environmental Agency. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Portale multimediale della Comunità italiana di Isola" (PDF). Retrieved 8 December 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.retecivica.trieste.it. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2004. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Article in Italian about the sinking of the battleship Queen Elizabeth Archived 7 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Press on "Vergerius, Petrus Paulus"[permanent dead link]. Istrianet.org. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "Odgovori na vprašanja članic in članov občinskega sveta" (PDF). koper.si (in Slovenian). Mestna občina Koper. 9 January 2021. p. 4. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

External links

[edit] Media related to Koper at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Koper at Wikimedia Commons- Koper on Geopedia

Koper travel guide from Wikivoyage

Koper travel guide from Wikivoyage- Koper–Capodistria. Slovenian Tourist Board.

- Koper: Virtual Tour. Panoramas of Koper and surrounding area. Burger.si.