Koonibba

| Koonibba South Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°54′14″S 133°25′31″E / 31.904006°S 133.425353°E[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 140 (SAL 2021)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1901 (Mission) 28 January 1999 (locality)[3][4] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5690[5] | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | ACST (UTC+9:30) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | ACST (UTC+10:30) | ||||||||||||||

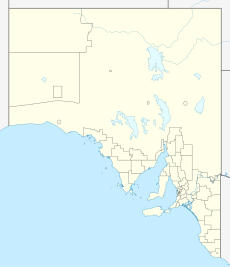

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | District Council of Ceduna[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Eyre Western[1] | ||||||||||||||

| County | Way[1] | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Flinders[6] | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Grey[7] | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Footnotes | Location[5] Adjoining localities[1] | ||||||||||||||

Koonibba is a locality and an associated Aboriginal community in South Australia located about 586 kilometres (364 mi) northwest of the state capital of Adelaide and about 38 km (24 mi) northwest of the municipal seat in Ceduna and 5 km (3.1 mi) north of the Eyre Highway.

The settlement grew around the Koonibba Mission (1901–1975). The Koonibba Football Club, founded in 1906, is the oldest Aboriginal football club still in existence. Koonibba Test Range is a rocket testing facility established in 2019.

History

[edit]Koonibba Mission

[edit]Koonibba was formerly an Aboriginal mission, founded in 1901 by the Lutheran Church on land comprising 16,000 acres (6,500 ha) which they bought in 1899.[3] The mission was established near the traditional lands of the Wirangu, Mirning, and Kokatha peoples.[10]

A school was built within a year,[3] with the church following in 1903. The church was built by two Aboriginal men named Thomas Richards and Mickey Free (Michael Free Lawrie). Aboriginal people came to the mission seeking employment, for which they were paid, but conversion to Christianity was a pre-condition for wages, food and housing.[10]

The South Australian Royal Commission on the Aborigines gathered evidence from the mission in 1914, and recommended that the mission be taken over by the government.[11][12][13]

In 1914, the Koonibba Children's Home was opened.[11]

After World War I ended in 1918, the mission stopped growing wheat, and started grazing sheep instead, which needed less labour, so people moved away for work.[10]

August Bernhard Carl Hoff was Superintendent of the mission from 1920 to 1930, and between 1920 and 1952 compiled a wordlist which was published by his son Lothar in 2004. The list included words from the Wirangu, Kokatha and Pitjantjatjara languages.[14][15]

In 1931 the Lutherans decided to sell the station, without any prior consultation with the residents. The residents petitioned the Church to work the land autonomously, but their request fell on deaf ears. No buyers were forthcoming, and farming ceased in 1993, but the church continued to control the lives of the residents until 1958, when the residents staged a walk-off as a protest.[10]

In 1963, the mission was taken over by the South Australian Government as an Aboriginal reserve, which in 1975 was transferred to the Aboriginal Land Trust. As of 2020[update] the site is leased to the local Aboriginal corporation, the Koonibba Aboriginal Community Council, which manages the community.[16]

"Koonibba Lutheran Children's Home" was listed in the 1997 Bringing Them Home report, as an institution housing Indigenous children forcibly removed from their families, leading to the Stolen Generations.[3]

The locality of Koonibba

[edit]Boundaries for a locality were created on 28 January 1999 for the long-established local name of Koonibba. The Eyre Highway forms part of the locality's southern boundary. In 2013, a portion of the locality which was located in the Yumbarra Conservation Park was removed and added to the new locality of Yumbarra to ensure that all of the conservation park was located within the new locality.[4][1]

Population and facilities

[edit]As of 2016[update], Koonibba and an adjoining part of the locality of Yumbarra has a population of 149, 87% of whom are Indigenous Australians.[9][1]

The settlement has a public school, the Koonibba Aboriginal School.[17]

An Australian rules football club, the Koonibba Football Club, was formed in 1906. It is the oldest Aboriginal football club still in existence, and plays in the Far West Football League today.[18]

A general store, giving locals access to fresh groceries for the first time in 40 years, was opened in February 2019.[19]

It is planned to develop tourist attractions, with a focus on the history of the settlement. Cultural artefacts as of September 2019[update] stored at the South Australian Museum would be put on display, to engender pride in the community and provide a learning experience for tourists.[19]

Heritage buildings

[edit]The Our Redeemer Lutheran Church from the former Koonibba Lutheran Mission survives and is listed on the South Australian Heritage Register.[20]

Koonibba Test Range

[edit]In 2019–2020, a private space company, Southern Launch, established the Koonibba Test Range after consultation with the Koonibba Community Aboriginal Corporation. It was reported that Southern Launch worked with companies, universities, space agencies and other organisations to have their rockets and payloads launched and recovered from the site, and that the Koonibba site was the world's largest privately owned rocket test range and the world's first approved by an indigenous community to be launched from their land.[21] The first launches were small rockets carrying small replica payloads on 19 September 2020.[22] In 2024, it was reported that the biggest satellite launched on Australian soil would be fired from this location.[23]

In the arts

[edit]Mazin Grace, by Dylan Coleman, is a fictionalised account of the author's mother's life as a Kokatha child growing up on Koonibba in the 1940s and 1950s, and includes a glossary of Aboriginal English and Kokatha words, which are used throughout the book.[24] It won the 2011 David Unaipon Award for Unpublished Indigenous Writer,[25] and was longlisted for the Stella Prize[24][26] and shortlisted for the Commonwealth Book Prize in 2013.[27]

Also based on her mother's experiences growing up at Koonibba, Coleman wrote and co-directed a short film (with brother Staurme Glastonbury), Secret Pretty Things (Jija Mooga Gu),[28][29] which was given its world premiere at the Adelaide Film Festival in October 2020 (preceding the feature documentary The Earth Is Blue as an Orange).[30]

Museum collection

[edit]Pastor Hoff's son Lothar (see above) was born at Koonibba Mission, and had inherited his father's collection of photographs and rare Kokatha and Wirangu artefacts after his death in 1971. In 2008 Lothar handed over the collection to the South Australian Museum.[31]

Notable people

[edit]Notable people associated with Koonibba include:

- Bart Willoughby OAM (born 1960), musician, founder of No Fixed Address[32]

See also

[edit]Other 19th century Aboriginal missions in SA

[edit]- Killalpaninna

- Point McLeay (Raukkan)

- Point Pearce

- Poonindie

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Search results for 'Koonibba, LOCB' with the following datasets selected - 'Suburbs and localities', 'Counties', 'Government Towns', 'Local Government Areas', 'SA Government Regions' and 'Gazetteer'". Location SA Map Viewer. South Australian Government. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Koonibba (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Koonibba Mission(1901 - 1975)". Find & Connect. 5 September 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b Kentish, P.M. (28 January 1999). "GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES ACT 1991 Notice to Assign Boundaries and Names to Places (in the District Council of Ceduna)" (PDF). The South Australian Government Gazette. Government of South Australia. p. 610. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Find a post - search result for Koonibba, South Australia". postcodes-australia.com. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ "District of Flinders Background Profile". Electoral Commission SA. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Federal electoral division of Grey" (PDF). Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ a b c "Monthly climate statistics: Summary statistics CEDUNA AMO (nearest station)". Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Koonibba". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Aboriginal missions in South Australia: Koonibba". State Library of South Australia. LibGuides. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Royal Commission on the Aborigines (1913 - 1916)". Find & Connect. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Royal Commission on the Aborigines" (PDF). South Australia. Government Printer. 1913. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Chapter 8 South Australia". Bringing Them Home. 1995. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Velichova-Rebelos, Margareta; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Hoff, Lothar C.; University of Adelaide. Discipline of Linguistics; Maintenance of Indigenous Languages and Records Program (Australia) (2005), Draft word list of the indigenous languages spoken at Koonibba Mission: featuring words from the Wirangu, Kokatha and Pitjantjatjara languages from the far West Coast of South Australia, Discipline of Linguistics, School of Humanities, University of Adelaide], retrieved 30 October 2020,

Extracted from The Hoff Vocabularies of Indigenous Languages collected by Reverend A.B.C. Hoff in 1920-1952.

- ^ Hoff, A. B. C. (August Bernhard Carl); Hoff, Lothar C (2004), The Hoff vocabularies of indigenous languages from the far west coast of South Australia, Lothar Hoff, ISBN 978-0-646-43758-3

- ^ "Koonibba Community". www.alt.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Department for Education". Koonibba Aboriginal School. 17 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Koonibba Football Club: Established 1906". Aboriginal Football: The Indigenous Game. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b "After 40 years, Koonibba community finally has general store". InDaily. 1 September 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Our Redeemer Lutheran Church of the former Koonibba Lutheran Mission". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 13 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Koonibba world's first indigenous community to host rocket takeoff; Southern Launch gets OK for more at the site". AdelaideAZ. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Barila, Greg (19 September 2020). "Southern Launch successfully launches rockets to edge of space from Koonibba in outback South Australia". Sunday Mail. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

subscription: the source is only accessible via a paid subscription ("paywall"). - ^ "SA to launch largest commercial rocket … fuelled by candle wax". Adelaide Now. 1 May 2025.

- ^ a b Fuss, Eloise (15 March 2013). "Acclaimed Aboriginal novel stems from family's pain". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. ABC North and West SA. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Mazin Grace". UQP. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Longlist 2013". The Stella Prize. 9 December 2013. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Austlit. "Mazin Grace". AustLit. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Secret Pretty Things - Jija Mooga Gu". SAFC. 26 October 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Dr Dylan Coleman". The University of Adelaide. Staff Directory. 6 July 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "The Earth Is Blue As An Orange". Adelaide Film Festival. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Lloyd, Tim (19 February 2008). "Aboriginal artefacts saved". Adelaide Now. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Martin, Kaya (9 May 2024). "Indigenous music pioneer Bart Willoughby honoured at the Australian Music Vault". Beat Magazine. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- "Aboriginal missions in South Australia: Koonibba". State Library of South Australia. LibGuides. 12 February 2020.

External links

[edit]- Koonibba Aboriginal Community

- "About Us". Southern Launch.