Paul Whiteman

Paul Whiteman | |

|---|---|

Whiteman in a 1939 publicity photo | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Paul Samuel Whiteman |

| Born | March 28, 1890 Denver, Colorado |

| Died | December 29, 1967 (aged 77) Doylestown, Pennsylvania |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1907–1960s |

Paul Samuel Whiteman[1] (March 28, 1890 – December 29, 1967)[2] was an American bandleader, composer, orchestral director, and violinist.[3]

As the leader of one of the most popular dance bands in the United States during the 1920s and early 1930s, Whiteman produced recordings that were immensely successful, and press notices often referred to him as the "King of Jazz". His most popular recordings include "Whispering", "Valencia", "Three O'Clock in the Morning", "In a Little Spanish Town", and "Parade of the Wooden Soldiers". Whiteman led a usually large ensemble and explored many styles of music, such as blending symphonic music and jazz, as in his debut of Rhapsody in Blue by George Gershwin.[4]

Whiteman recorded many jazz and pop standards during his career, including "Wang Wang Blues", "Mississippi Mud", "Rhapsody in Blue", "Wonderful One", "Hot Lips (He's Got Hot Lips When He Plays Jazz)", "Mississippi Suite", "Grand Canyon Suite", and "Trav'lin' Light". He co-wrote the 1925 jazz classic "Flamin' Mamie". His popularity faded in the swing music era of the mid-1930s, and by the 1940s he was semi-retired from music. He experienced a revival and had a comeback in the 1950s with his own network television series, Paul Whiteman's Goodyear Revue, which ran for three seasons on ABC. He also hosted the 1954 ABC talent contest show On the Boardwalk with Paul Whiteman.

Whiteman's place in the history of early jazz is somewhat controversial. Detractors suggest that his ornately orchestrated music was jazz in name only, lacking the genre's improvisational and emotional depth, and co-opted the innovations of black musicians. Defenders note that Whiteman's fondness for jazz was genuine. He worked with black musicians as much as was feasible during an era of racial segregation. His bands included many of the era's most esteemed white musicians, and his groups handled jazz admirably as part of a larger repertoire.[5]

Critic Scott Yanow declares that Whiteman's orchestra "did play very good jazz...His superior dance band used some of the most technically skilled musicians of the era in a versatile show that included everything from pop tunes and waltzes to semi-classical works and jazz. [...] Many of his recordings (particularly those with Bix Beiderbecke) have been reissued numerous times and are more rewarding than his detractors would lead one to believe."[6]

In his autobiography, Duke Ellington declared, "Paul Whiteman was known as the King of Jazz, and no one as yet has come near carrying that title with more certainty and dignity."[7]

Early life

[edit]

Whiteman was born in Denver, Colorado.[2] He came from a musical family: his father, Wilburforce James Whiteman[8] was the supervisor of music for the Denver Public Schools, a position he held for fifty years,[9] and his mother Elfrida (née Dallison) was a former opera singer. His father insisted that Paul learn an instrument, preferably the violin, but the young man chose the viola.[10] Whiteman was Protestant and of Scottish, Irish, English, and Dutch ancestry.[11]

Career

[edit]Whiteman's skill at the viola resulted in a place in the Denver Symphony Orchestra by 1907, joining the San Francisco Symphony in 1914. In 1918, Whiteman conducted a 12-piece U.S. Navy band, the Mare Island Naval Training Camp Symphony Orchestra (NTCSO).[12] After World War I, he formed the Paul Whiteman Orchestra.[13]

That year he led a popular dance band in the city. In 1920, he moved with his band to New York City where they began recording for the Victor Talking Machine Company.[2] The popularity of these records led to national fame. In his first five recordings sessions for Victor, August 9 – October 28, 1920, he used the name "Paul Whiteman and His Ambassador Orchestra", presumably because he had been playing at the Ambassador Hotel in Atlantic City. From November 3, 1920, he started using "Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra."[14]

Whiteman became the most popular band director of that decade. In a time when most dance bands consisted of six to ten men, Whiteman directed a more imposing group that numbered as many as 35 musicians. By 1922, Whiteman already controlled some 28 ensembles on the East Coast and was earning over $1,000,000 a year.[15]

In 1926, Paul Whiteman was on tour in Vienna, Austria when he met and was interviewed by a young ambitious newspaper reporter named Billy Wilder who was also a fan of Whiteman's band.[16] Whiteman liked young Wilder enough, that he took him with the band to Berlin where Wilder was able to make more connections in the entertainment field, leading him to become a screenwriter and director, eventually ending up in Hollywood.

In 1927, the Whiteman orchestra backed Hoagy Carmichael singing and playing on a recording of "Washboard Blues".[17] Whiteman signed with Columbia Records in May 1928, leaving the label in September 1930 when he refused a pay cut. He returned to RCA Victor between September 1931 and March 1937.

"The King of Jazz"

[edit]Beginning in 1923 after the Buescher Band Instrument Company placed a crown on his head, the media referred to Whiteman as "The King of Jazz".[18] Whiteman emphasized the way he approached the well-established style of jazz music, while also organizing its composition and style in his own fashion.[2]

While most jazz musicians and fans consider improvisation to be essential to the musical style, Whiteman thought the genre could be improved by orchestrating the best of it, with formal written arrangements.[2] Eddie Condon criticized him for trying to "make a lady" out of jazz.[4] Whiteman's recordings were popular critically and commercially, and his style of jazz was often the first jazz of any form that many Americans heard during the era. Whiteman wrote more than 3000 arrangements.[19]

For more than 30 years Whiteman, referred to as "Pops", sought and encouraged promising musicians, vocalists, composers, arrangers, and entertainers. In 1924 he commissioned George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, which was premiered by his orchestra with the composer at the piano.[2] Another familiar piece in Whiteman's repertoire was Grand Canyon Suite by Ferde Grofé.

Paul Whiteman And His Orchestra

[edit]Whiteman hired many of the best jazz musicians for his band, including Bix Beiderbecke, Frankie Trumbauer, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang, Steve Brown, Mike Pingitore, Gussie Mueller, Wilbur Hall (billed by Whiteman as "Willie Hall"), Jack Teagarden, and Bunny Berigan.[2] He encouraged upcoming African American musical talents and planned to hire black musicians, but his management persuaded him that doing so would destroy his career, due to racial tension and America's segregation of that time.[5]

In 1925, seeking to break up his musical selections, Whiteman's attention was directed by a member of his organisation to Bing Crosby and Al Rinker, who would perform as members of his orchestra, and later, as two of the three frontmen of The Rhythm Boys.[20]

He provided music for six Broadway shows and produced more than 600 phonograph recordings.[19] His recording of José Padilla's "Valencia" was a big hit in 1926.[21]

Red McKenzie, leader of the Mound City Blue Blowers, and cabaret singer Ramona Davies (billed as "Ramona and her Grand Piano") joined the Whiteman group in 1932. The King's Jesters were with Paul Whiteman in 1931. In 1933, Whiteman had a hit on the Billboard charts with Ann Ronell's "Willow Weep for Me".[22]

In 1942, Whiteman began recording for Capitol Records, co-founded by songwriters Buddy DeSylva and Johnny Mercer and music store owner Glenn Wallichs. Whiteman and His Orchestra's recordings of "I Found a New Baby" and "The General Jumped at Dawn" was the label's first single release.[23] Another notable Capitol record he made is the 1942 "Trav'lin Light" featuring Billie Holiday (billed as "Lady Day", due to her being under contract with another label).[23]

Film appearances

[edit]

Whiteman appeared as himself in the 1945 movie Rhapsody in Blue on the life and career of George Gershwin,[2] and also appeared in The Fabulous Dorseys in 1947, a bio-pic starring Jimmy Dorsey and Tommy Dorsey. Whiteman also appeared as the baby in Nertz (1929), the bandleader in Thanks a Million (1935),[2] as himself in Strike Up the Band (1940),[2] in the Paramount Pictures short The Lambertville Story (1949), and the revue musical King of Jazz (1930).[2]

Radio and TV

[edit]Although giving priority to stage appearances during his peak years in the 1920s, Whiteman participated in some early prestigious radio programs. On January 4, 1928, Whiteman and his troupe starred in a nationwide NBC radio broadcast sponsored by Dodge Brothers Automobile Co. and known as The Victory Hour (The program introduced the new Dodge "Victory Six" automobile). It was the most widespread hookup ever attempted at that time. Will Rogers acted as MC and joined the program from the West Coast, with Al Jolson coming in from New Orleans.[24] Variety was not impressed, saying: "As with practically all of the important and high-priced commercial broadcasting programs under N.B.C. auspices in the past, the Dodge Brothers' Victory Hour at a reputed cost of $67,000 was disappointing and not commensurate in impression with the financial outlay." However, the magazine noted. "...The reaction to Paul Whiteman's grand radio plug for "Among My Souvenirs"…was a flock of orders by wire from dealers the day following the Dodge Brothers Victory Hour broadcast."[25]

On March 29, 1928, Whiteman took part in a second Dodge Brothers radio show over the NBC network, which was entitled Film Star Radio Hour.[26] Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, John Barrymore, and several other Hollywood stars were featured. United Artists Pictures arranged for additional loudspeakers to be installed in their theatres so that audiences could hear the stars they had only seen in silent pictures previously. The New York Herald Tribune commented: "...Of Mr. Paul Whiteman's share in the pretentious program, only the best can be said. Mr. Whiteman's orchestra is seldom heard on the radio, and its infrequent broadcasts are the subject of major jubilations, despite the presence of tenors and vocal harmonists in most of the Whiteman renditions."[27]

In 1929, Whiteman agreed to take part in a weekly radio show for Old Gold Cigarettes for which he was paid $5,000 per broadcast. Old Gold Presents Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra was an hour-long show on Tuesday nights over CBS from station WABC in New York. The Whiteman Hour had its first broadcast on February 5, 1929, and continued until May 6, 1930. On May 7, 1930, he was paid $325,000 for 65 radio episodes.[28]

Whiteman then became far busier in radio. His shows were:

- January 27, 1931 – July 1, 1932, Blue Network. 30m, Tuesdays at 8, then Fridays at 10. Allied Paints (1931), Pontiac (1932).

- July 8, 1932 – March 27, 1933, NBC. 30m, Fridays at 10, then Mondays at 9:30. Pontiac (to September), then Buick.

- June 26, 1933 – December 26, 1935. NBC. 60m, Thursdays at 10. The Kraft Music Hall, often with Al Jolson.

- January 5 – December 27, 1936, Blue Network. 45m. Sundays variously at 9, 9:15, and 9:45. Paul Whiteman's Musical Varieties. Woodbury Soap. With Bob Lawrence, Johnny Hauser, Morton Downey, Durelle Alexander, songs by the King's Men, and announcer Roy Bargy. The show featured a children's amateur contest. Near the end of the run Whiteman introduced comedian Judy Canova, who inherited timeslot and sponsor in the Woodbury Rippling Rhythm Revue.

- December 31, 1937 – December 20, 1939, CBS. 30m. Fridays at 8:30 until mid–July 1938, then Wednesdays at 8:30. Chesterfield Time, with Joan Edwards, Deems Taylor (musical commentary) and announcer Paul Douglas. Whiteman took over the slot vacated by Hal Kemp and two years later vacated it for the sensational new Glenn Miller orchestra.

- November 9 – December 28, 1939, Mutual. 30m, Thursdays at 9:30.

- June 6 – August 29, 1943, NBC. 30m, Sundays at 8. Paul Whiteman Presents. Summer substitute for Edgar Bergen. Chase and Sanborn.

- December 5, 1943 – April 28, 1946, Blue/ABC. 60m. Sundays at 6. Paul Whiteman's Radio Hall of Fame. Philco.

- September 5 – November 14, 1944, Blue Network, 30m, Tuesdays at 11:30. Music of current American composers.

- January 21 – September 23, 1946, ABC. 30m, Mondays at 9:30. Forever Tops. "a weekly program featuring the top tunes of the day."[29]

- September 29 – October 27, 1946, ABC. 60m, Sundays at 8. The Paul Whiteman Hour. Extended until November 17, 1947, as a 30m show, The Paul Whiteman Program, various days and times.

- June 30, 1947 – June 25, 1948, ABC. 60m, five a week at 3:30. The Paul Whiteman Record Program. Glorified disc–jockeyism.

- September 29, 1947 – May 23, 1948, ABC. 30m, Mondays at 8, then at 9 after October On Stage America, for the National Guard. Whiteman's orchestra with John Slagle, George Fenneman, etc. Producer: Roland Martini. Director: Joe Graham. Writer: Ira Marion.

- June 27 – November 7, 1950, ABC. 30m, Tuesdays at 8. Paul Whiteman Presents.

- October 29, 1951 – April 28, 1953, ABC. Various times. Paul Whiteman's Teen Club. An amateur hour with the accent on youth.[30]

- February 4 – October 20, 1954. ABC. 30m. Thursdays at 9 until July, then Wednesdays at 9:30. Paul Whiteman Varieties.[31]

In the 1940s and 1950s, after he had disbanded his orchestra, Whiteman worked as a music director for the ABC Radio Network.[2] He also hosted Paul Whiteman's TV Teen Club from Philadelphia on ABC-TV from 1949 to 1954. The show was seen for an hour the first two years, then as a half-hour segment on Saturday evenings. In 1952 a young Dick Clark read the commercials for sponsor Tootsie Roll.[32] Whiteman's TV-Teen Club, along with Grady and Hurst's 950 Club, proved to be an inspiration for WFIL-TV's afternoon dance show called American Bandstand.[33]

He also continued to appear as guest conductor for many concerts. His manner on stage was disarming; he signed off each program with something casual like, "Well, that just about slaps the cap on the old milk bottle for tonight." In the early 1960s, Whiteman played in Las Vegas before retiring.[4]

Personal life and death

[edit]On August 18, 1931, Whiteman married for the fourth and final time to actress Margaret Livingston in a ceremony in Denver, Colorado. Livingston was unable to have children, and the couple adopted four.[34][35]

Whiteman lived at Walking Horse Farm near the village of Rosemont in Delaware Township, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, from 1938 to 1959. After selling the farm to agriculturalist Lloyd Wescott, Whiteman moved to New Hope, Pennsylvania, for his remaining years.[36][37][38]

Paul Whiteman died of a heart attack on December 29, 1967, in Doylestown Hospital, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, aged 77.[39] He is buried at First Presbyterian Church of Ewing Cemetery in Trenton, New Jersey.[40] [41]

Motorsports

[edit]Whiteman was a close friend of NASCAR and Daytona International Speedway founder Bill France.[42]

On June 13, 1954, the #4 Jaguar XK120, driven by Al Keller, won the International 100 race of the Grand National series, held on a one mile road course on the airport at Vineland, New Jersey. This was the first, and so far only, victory by a European car in NASCAR's top series. The car was owned by Ed Otto, race promoter and co-founder of NASCAR, but was entered under the ownership of Whiteman to avoid issues arising from conflicts of interest - Keller won a $1,000 first prize, and Whiteman's registration as owner survives in archives.[43][44]

The #7 Cadillac owned by Whiteman ran in five Nascar Grand National races during the 1954 season, with future Hall of Famer Junior Johnson driving in three and Gwyn Staley driving in two. In the 1955 season, it ran in one race with Junior Johnson driving.[45][46]

"Paul Whiteman Trophy" races, arranged by the Central Florida Region SCCA, were held from 1958 until 1972.[47] The 1958 event was held at the New Smyrna Beach Airport,[48] and from 1961, it was held annually at the Daytona Speedway.[49]

Songs

[edit]

The Paul Whiteman Orchestra introduced many jazz standards in the 1920s, including "Hot Lips", which was in the Steven Spielberg movie The Color Purple (1985), "Mississippi Mud", "From Monday On", written by Harry Barris and sung by the Rhythm Boys featuring Bing Crosby and Irene Taylor with Bix Beiderbecke on cornet, "Nuthin' But", "Grand Canyon Suite" and "Mississippi Suite" composed by Ferde Grofé, "Rhapsody in Blue", composed by George Gershwin who played piano on the Paul Whiteman recording in 1924, "Wonderful One" (1923), and "Wang Wang Blues" (1920), covered by Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Joe "King" Oliver's Dixie Syncopators in 1926 and many of the Big Bands. "Hot Lips" was recorded by Ted Lewis and His Jazz Band, Horace Heidt and His Brigadiers Orchestra (1937), Specht's Jazz Outfit, the Cotton Pickers (1922), and Django Reinhardt et Le Quintette Du Hot Club De France.

Paul Whiteman was the first to release the jazz and pop standard "Deep Purple" as an instrumental in 1934.[50]

Compositions

[edit]Whiteman composed the standard "Wonderful One" in 1922 with Ferde Grofé and Dorothy Terris (also known as Theodora Morse), based on a theme by film director Marshall Neilan. The songwriting credit is assigned as music composed by Paul Whiteman, Ferde Grofé, and Marshall Neilan, with lyrics by Dorothy Terriss. The single reached No. 3 on Billboard in May 1923, staying on the charts for 5 weeks. "(My) Wonderful One" was recorded by Gertrude Moody, Edward Miller, Martha Pryor, Mel Torme, Doris Day, Woody Herman, Helen Moretti, John McCormack; it was released as Victor 961. Jan Garber and His Orchestra, and Ira Sullivan with Tony Castellano also recorded the song. Henry Burr recorded it in 1924 and Glenn Miller and his Orchestra in 1940. On the sheet music published in 1922 by Leo Feist it is described as a "Waltz Song" and "Paul Whiteman's Sensational Waltz Hit" and is dedicated "To Julie". "Wonderful One" appeared in the following movies: The Chump Champ (1950), Little 'Tinker (1948), Red Hot Riding Hood (1943), Sufferin' Cats (1943), Design for Scandal (1941), Strike Up the Band (1940), and Westward Passage (1932).

"I've Waited So Long" was composed with Irving Bibo and Howard Johnson and copyrighted in 1920.[51][52] Whiteman also arranged the song. "How I Miss You Mammy, No One Knows" was composed with Billy Munro and Marcel Klauber in 1920 and arranged by Marcel Klauber.[53]

The 1924 song "You're the One" was composed by Paul Whiteman, Ferde Grofé, and Ben Russell in 1924 and copyrighted on February 1, 1924.[54]

He co-wrote the music for the song "Madeline, Be Mine" in 1924 with Abel Baer with lyrics by Cliff Friend.[55]

Whiteman composed the piano work "Dreaming The Waltz Away" with Fred Rose in 1926.[56][57] Organist Jesse Crawford recorded the song on October 4–5, 1926, in Chicago, Illinois, and released it as a 78 on Victor Records, 20363. Crawford played the instrumental on a Wurlitzer organ. The recording was also released in the UK on His Master's Voice (HMV) as B2430.

In Louis Armstrong & Paul Whiteman: Two Kings of Jazz (2004), Joshua Berrett wrote that "Whiteman Stomp" was credited to Fats Waller, Alphonso Trent, and Paul Whiteman. Lyricist Jo Trent is the co-author. The Fletcher Henderson Orchestra first recorded "Whiteman Stomp" on May 11, 1927, and released it as Columbia 1059-D. The Fletcher Henderson recording lists the songwriters as "Fats Waller/Jo Trent/Paul Whiteman".[58] Whiteman recorded the song on August 11, 1927, and released it as Victor 21119.

On May 31, 1924, the song "String Beans" was copyrighted, with words and music by Vincent Rose, Harry Owens, and Paul Whiteman.[59]

In 1927, Paul Whiteman co-wrote the song "Wide Open Spaces" with Byron Gay and Richard A. Whiting.[60] The Colonial Club Orchestra released a recording of the song on Brunswick Records in 1927 as 3549-A with Irving Kaufman on vocals.

In 1920, he co-wrote the music to the song "Bonnie Lassie" with Joseph H. Santly with lyrics by John W. Bratton.[61] The song was recorded by Charles Hart who released it as an Okeh 78 single, 4244.[62]

Whiteman also co-wrote the popular song "My Fantasy" with Leo Edwards and Jack Meskill, which is a musical adaptation of the Polovtsian Dances theme from the opera Prince Igor by Alexander Borodin. The Paul Whiteman Orchestra recorded "My Fantasy" with Joan Edwards on vocals in 1939 and released it as a 78 single on Decca Records. Artie Shaw also recorded the song and released it as a single on Victor Records in March 1940 with Pauline Byrns on vocals.[63]

Awards and honors

[edit]In 2006 the Paul Whiteman Orchestra's 1928 recording of Ol' Man River with Paul Robeson on vocals was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. The song was recorded on March 1, 1928, in New York and released as Victor 35912-A.[64]

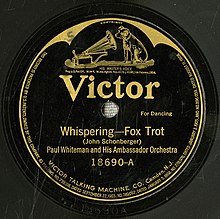

In 1998, the 1920 Paul Whiteman recording of "Whispering" was inducted in the Grammy Hall of Fame.[65]

Paul Whiteman's 1927 recording of "Rhapsody in Blue", of which was an electrically recorded version, was inducted in the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1974.[66]

He was inducted in the Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame in 1993.

He was awarded two Stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for Recording at 6157 Hollywood Boulevard and for Radio at 1601 Vine Street in Hollywood.[67]

He had two songs listed in the National Recording Registry, the first was the June 1924 performance of Rhapsody In Blue, with George Gershwin on piano, which was listed in 2003.[68] The second one was the song "Whispering", which was listed in 2020.[69]

On April 16, 2016, Paul Whiteman was inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame.[70][71]

Major recordings

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

- "Whispering", 1920, 1998 Grammy Hall of Fame inductee. Sold nearly two million copies by 1921, awarded gold disc.[72]

- "The Japanese Sandman", 1920

- "Wang Wang Blues", 1921, 1,000,000 sales,[73] on the soundtrack to the 1996 Academy Award-winning movie The English Patient

- "My Mammy", 1921, 1,000,000 sales[73]

- "Cherie", 1921, 405,647 sales[74]

- "Say It With Music", 1921

- "Song of India", 1921, 1,000,000 sales,[73] music adapted by Paul Whiteman from the Chanson Indoue theme by Nikolai Rimski-Korsakov from the opera Sadko (1898)

- "Hot Lips (He's Got Hot Lips When He Plays Jazz)", 1922, 1,000,000 sold,[73] featured in the motion picture The Color Purple (1985)

- "Do It Again", 1922, 523,106 sold[74]

- "Three O'Clock in the Morning", 1922, 3,000,000 sold[72]

- "Stumbling", 1922

- "Wonderful One", 1922, music composed by Paul Whiteman and Ferde Grofé, with lyrics by Theodora Morse

- "I'll Build a Stairway to Paradise", 1923

- "Parade of the Wooden Soldiers", 1923, 722,895 sales[74]

- "Bambalina", 1923

- "Nuthin' But", 1923, co-written by Ferde Grofé and Henry Busse

- "Linger Awhile", 1924, 1,000,000 sales[75][74]

- "What'll I Do", 1924, 538,434 sales[74]

- "Somebody Loves Me", 1924, 678,403 sales[74]

- "Rhapsody in Blue", 1924, acoustical version, arranged by Ferde Grofé, with George Gershwin on piano

- "When the One You Love Loves You", 1924, composed by Paul Whiteman

- "Last Night on the Back Porch", 1924, 427,784 sales[74]

- "Oh, Lady Be Good!", 1924

- "All Alone", 1925, 835,586 sales[74]

- "Indian Love Call", 1925, 526,884 sales[74]

- "Charlestonette", 1925, composed by Paul Whiteman with Fred Rose

- "Birth of the Blues", 1926

- "Valencia", 1926, 1,012,687 sales[74]

- "My Blue Heaven", 1927

- "Three Shades of Blue: Indigo/Alice Blue/Heliotrope", 1927, composed and arranged by Ferde Grofé

- "In a Little Spanish Town", 1927, 1,000,000 sales

- "I'm Coming Virginia"

- "Washboard Blues", 1927, with Hoagy Carmichael on vocals and piano

- "Rhapsody in Blue", 1927, electrical version, Grammy Hall of Fame inductee

- "From Monday On", 1928, with Bing Crosby, the Rhythm Boys, and Jack Fulton on vocals and Bix Beiderbecke on cornet

- "Mississippi Mud", 1928, with Bing Crosby and Bix Beiderbecke

- "Metropolis: A Blue Fantasy", 1928, composed by Ferde Grofé, with Bix Beiderbecke on cornet

- "Ol' Man River", 1928, first, fast version, with Bing Crosby on vocals

- "Ol' Man River", 1928, second, slow version, with Paul Robeson on vocals, Grammy Hall of Fame inductee

- "Concerto in F"

- "Among My Souvenirs", 1928

- "Ramona", 1928, with Bix Beiderbecke

- "Together", 1928, with Jack Fulton on vocals.

- "My Angel", 1928, with Bix Beiderbecke

- "Great Day", 1929

- "Body and Soul", 1930

- "New Tiger Rag", 1930

- "When It's Sleepy Time Down South", 1931, vocal by Mildred Bailey and the King's Jesters

- "Grand Canyon Suite", 1932

- "All of Me" (vocal Mildred Bailey), 1932, 12,161 sales[76]

- "Let's Put Out the Lights (and Go to Sleep)" (Vocal Ramona Davies), 1932, 11,942 sales[77]

- "Willow Weep for Me", vocal refrain by Irene Taylor, 1933, 8,292 sales (second highest total 1933).[78]

- "It's Only a Paper Moon", 1933, with Peggy Healy on vocals. The Whiteman recording, Victor 24400, was used in the 1973 movie Paper Moon

- "Deep Purple, he was the first to release the jazz and pop standard, 1934[79]

- "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" (vocal Bob Lawrence), 1934, Jazz Standards

- "You're the Top", 1934

- "Fare-Thee-Well to Harlem", 1934, with vocals by Johnny Mercer and Jack Teagarden

- "Wagon Wheels" (vocal Bob Lawrence), 1934

- "My Fantasy", 1939, Paul Whiteman co-wrote the song, an adaptation by Paul Whiteman of the Polovtsian Dances theme from the opera Prince Igor by Alexander Borodin, credited to "Paul Whiteman/Leo Edwards/Jack Meskill". Artie Shaw recorded "My Fantasy" in 1940.

- "Trav'lin' Light", 1942, with Billie Holiday on vocals; no. 1 for 3 weeks on the Billboard Harlem Hit Parade chart; no. 23 on the pop singles chart in 1942; V-Disc No. 286A, released in October 1944 by the U.S. War Department.

Grammy Hall of Fame

[edit]Paul Whiteman was posthumously inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, which is a special Grammy award established in 1973 to honor recordings that are at least 25 years old and that have "qualitative or historical significance."

| Year recorded | Title | Genre | Label | Year inducted | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | "Whispering" | Jazz (single) | Victor | 1998 | |

| 1927 | "Rhapsody in Blue" | Jazz (single) | Victor | 1974 | |

| 1928 | "Ol' Man River" (Paul Robeson, vocal) | Jazz (single) | Victor | 2006 |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Delong, Thomas (1983). Pops: Paul Whiteman, King of Jazz. El Monte: New Win Pub. ISBN 978-0-832-902642.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Colin Larkin, ed. (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise ed.). Virgin Books. p. 1248. ISBN 1-85227-745-9.

- ^ "Paul Whiteman - American bandleader". Britannica.com. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Paul Whiteman 'The King of Jazz' (1890–1967)". Red Hot Jazz. April 13, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ a b DeVeaux, Scott; Giddins, Gary (2009). Jazz (1 ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06861-0.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "Paul Whiteman". AllMusic. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ Ellington, Edward Kennedy (1973). Music is My Mistress (Repr. d. Ausg. Garden City, N.Y. ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. p. 103. ISBN 0-306-80033-0.

- ^ "Answers to Questions," Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 2, 1935, p. M-10.

- ^ "Paul Whiteman Dead at 77 of Heart Attack", Rockford IL Register-Republic, December 29, 1967, p. 1.

- ^ "Music Industry Giant, Paul Whiteman Dead at 77", Boston Herald, December 30, 1967, p. 10.

- ^ "Big Band Library: Paul Whiteman: "Something to Remember You By"". Bigbandlibrary.com.

- ^ Don Rayno, _Paul Whiteman: Pioneer in American Music_ Vol. 1

- ^ "Paul Whiteman: American Bandleader". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ Albert Haim, "Paul Whiteman and His Ambassador Orchestra", network54.com; accessed January 7, 2016.

- ^ "History of Jazz Time Line: 1922". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (March 29, 2002). "Billy Wilder, Master of Caustic Films, Dies at 95". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ Wilder, Alec (1990). American Popular Song: The Great Innovators 1900–1950. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-501445-6.

- ^ Berrett, Joshua (2004). Louis Armstrong & Paul Whiteman: Two Kings of Jazz. Yale University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-300-10384-7.

- ^ a b "Paul Whiteman Biography". PBS. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ Macfarlane, Malcolm (2001). Bing Crosby: Day by Day. Scarecrow Press.

- ^ CD liner notes: Chart-Toppers of the Twenties, 1998 ASV Ltd.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1996). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits (6. ed., rev. and enl. ed.). New York: Billboard Publications. ISBN 9780823076321.

- ^ a b Vera, Billy (2000). From the Vaults Vol. 1: The Birth of a Label - the First Years (CD). Hollywood: Capitol Records. p. 2.

- ^ Rayno, Don (2003). Paul Whiteman - Pioneer in American Music - Volume 1: 1890-1930. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 183. ISBN 0-8108-4579-2.

- ^ "Variety". Variety. January 11, 1928.

- ^ Rayno, Don (2003). Paul Whiteman - Pioneer in American Music - Volume 1: 1890-1930. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 192. ISBN 0-8108-4579-2.

- ^ "New York Herald Tribune". New York Herald Tribune. March 30, 1928.

- ^ Pairpoint, Lionel. "...And Here's Bing!". BING magazine. International Club Crosby. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (1999). Radio Programs, 1924–1984: A Catalog of More Than 1800 Shows. McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-4513-4. Pp. 510–511.

- ^ Woolery, George W. (1985). Children's Television: The First Thirty-Five Years, 1946-1981, Part II: Live, Film, and Tape Series. The Scarecrow Press. pp. 388–390. ISBN 0-8108-1651-2.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air - The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0-19-507678-8.

- ^ The complete directory to prime time network and cable TV shows, 1946–present. Tim Brooks, Earle Marsh. pp 918, 919

- ^ Jackson, John A., American Bandstand - Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock 'n' Roll Empire, Oxford University Press (1997)

- ^ "Margaret Livingston". The New York Times. January 16, 1985.

- ^ Slide, Anthony (March 12, 2012). The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781617032509.

- ^ "Entertainers". Time. March 6, 1944. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ^ "Stockton". Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park. Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ^ "Bucks County Artists". James A. Michener Art Museum. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ^ "Paul Whiteman, 'the Jazz King' of the Jazz Age, is Dead at 77; Made Jazz Respectable". The New York Times. December 30, 1967.

- ^ Spencer, Thomas E. (1998). Where They're Buried: A Directory Containing More Than Twenty Thousand Names of Notable Persons Buried in American Cemeteries, with Listings of Many Prominent People who Were Cremated. Genealogical Publishing Com. ISBN 978-0-8063-4823-0.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (August 19, 2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2599-7.

- ^ "Seen At Daytona 1957 | Hemmings". Hemmings.com. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "12 Wild and Wonderful NASCAR Oddities | NASCAR Hall of Fame | Curators' Corner". Nascar Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Race Results - Racing-Reference". Racing-reference.info. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Junior Johnson drove this Cadillac in the NASCAR Cup race at..." Getty Images. NASCAR/International Speedway Corporation Images & Archives via Getty Images. May 18, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Owner - Racing-Reference". Racing-reference.info. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ Times, Frank M. Blunkspecial To the New York (February 17, 1958). "Shepard Beats Casner by Lap In 96-Mile Florida Auto Race; Tampa Driver Leads Throughout Paul Whiteman Trophy Test, Averaging 79.02 M.P.H. in Maserati 200". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "New Smyrna Beach Airport 1958 - Race Results - Racing Sports Cars". Racingsportscars.com. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Daytona 1960-1973 - List of Races - Racing Sports Cars". Racingsportscars.com. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Deep Purple", first release on September 26, 1934 by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra. Second Hand Songs. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1920). Catalog of Copyright Entries: Musical compositions. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1842. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ Catalog of Copyright Entries, 1948. Copyright renewal by Paul Whiteman, I.M. Bibo, and Edna L. Johnson, google.com; accessed January 7, 2017.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1920). Catalog of Copyright Entries: Musical compositions. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1690. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1952). Catalog of Copyright Entries: Third series. pp. 1–95. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1952). Catalog of Copyright Entries: Third series. pp. 1–143. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "Victor Discography: Paul Whiteman (composer)". Victor.library.ucsb.edu. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1953). Catalog of Copyright Entries: Third series. pp. 1–125. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ Fletcher Henderson Orchestra profile, Discogs.com; accessed January 7, 2017.

- ^ "Catalog of Copyright Entries Series, 1951". Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Catalog of Copyright Entries 1954 Renewal Registrations-Music Jan-Dec 3D Ser Vol 8 Pt 5C". Archive.org. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1920). Catalog of Copyright Entries. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1268. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "Paul Whiteman". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Rayno, Don (2003). Paul Whiteman: Pioneer in American Music. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 705. ISBN 978-0-8108-8204-1.

- ^ Abrams, Steven and Settlemier, Tyrone. "The Online Discographical Project: Victor 35500 – 36000 numerical listing". Retrieved December 26, 2010.

- ^ "Grammy Hall of Fame. "Whispering" by Paul Whiteman. Grammy.org". grammy.org. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "Grammy Hall of Fame. 1974 inductions. George Gershwin with Paul Whiteman. 1927 recording. Grammy.org". grammy.org. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: Paul Whiteman". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. December 30, 1967.

- ^ "Complete National Recording Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Ulaby, Neda (March 25, 2020). "National Recording Registry Announces 2020 Entries, From Dr. Dre To Mister Rogers". NPR. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Paul Whiteman | Colorado Music Hall of Fame". cmhof.org. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "20th Century Pioneers Exhibit | Colorado Music Hall of Fame". cmhof.org. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Murrells, Joseph (1978). The book of golden discs. Internet Archive. London : Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 978-0-214-20512-5.

- ^ a b c d "Jazz History: The Standards (1920s)". Jazzstandards.com. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Victor Talking Machine Company". davidsarnoff.org. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1986). Joel Whitburn's Pop Memories 1890–1954. Record Research.

- ^ "Victor 22879 (Black label (popular) 10-in. double-faced) - Discography of American Historical Recordings". adp.library.ucsb.edu. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ "Victor 24140 (Black label (popular) 10-in. double-faced) - Discography of American Historical Recordings". adp.library.ucsb.edu. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ "Victor 24187 (Black label (popular) 10-in. double-faced)". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "Deep Purple", first release on September 26, 1934 by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra. Second Hand Songs. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "GRAMMY Hall of Fame | GRAMMY.org". Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

References

[edit]- Whiteman, Paul (1926). Jazz. J. H. Sears.

- Whiteman, Margaret Livingston; Leighton, Isabel (1933). Whiteman's Burden. Viking Press. ASIN B000856DAI.

- Whiteman, Paul; Lieber, Leslie (1948). How To Be A Band Leader. Robert McBride & Company.

- DeLong, Thomas A. (1983). Pops: Paul Whiteman, King of Jazz. New Century Publishers. ISBN 978-0832902642.

- Rayno, Don (2003). Paul Whiteman: Pioneer in American Music, 1890-1930 (Studies in Jazz). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810845794.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Paul Whiteman at the Internet Archive

- Paul Whiteman at IMDb

- Paul Whiteman at the Internet Broadway Database

- Paul Whiteman discography at Discogs

- Paul Whiteman recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- Paul Whiteman and His Concert Orchestra with George Gershwin on piano "Rhapsody in Blue", 1924 at Library of Congress

- Paul Whiteman (1890-1967) at the Red Hot Jazz Archive

- Paul Whiteman: Profiles in Jazz at The Syncopated Times

- Paul Whiteman collection at Williams College Archives & Special Collections

- Paul Whiteman: His Music And Memories - WPBS Philadelphia 1967 at YouTube: Radio station retrospective broadcast shortly after Whiteman's death; includes clips from a 1966 interview, musical selections, and many photographs

- 1924 song "Doo Wacka Doo", vocals by Billy Murray

- Whiteman, Susan. "Paul Whiteman (1890-1967)". University at Albany, SUNY.

- Paul Whiteman

- 1890 births

- 1967 deaths

- 20th-century American conductors (music)

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American jazz composers

- American male conductors (music)

- American jazz bandleaders

- American radio personalities

- Big band bandleaders

- Columbia Records artists

- American male jazz composers

- Musicians from Denver

- Musicians from New Rochelle, New York

- Jazz musicians from Colorado

- Jazz musicians from New York City

- Musicians from Bucks County, Pennsylvania

- People from Hunterdon County, New Jersey

- American vaudeville performers

- Victor Records artists

- United States Navy personnel of World War I