The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

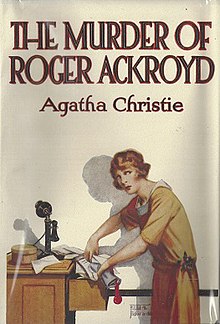

First edition | |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Ellen Edwards |

| Language | English |

| Series | Hercule Poirot |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Publisher | William Collins, Sons[1] |

Publication date | 1926[1] |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 312[1] |

| Preceded by | The Murder on the Links |

| Followed by | The Big Four |

| Text | The Murder of Roger Ackroyd online |

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is a detective novel by the British writer Agatha Christie, her third to feature Hercule Poirot as the lead detective. The novel was published in the UK in June 1926 by William Collins, Sons,[2] having previously been serialised as Who Killed Ackroyd? between July and September 1925 in the London Evening News. An American edition by Dodd, Mead and Company followed in 1926.[3]

The novel was well received from its first publication,[4][5] and has been called Christie's masterpiece.[6] In 2013, the British Crime Writers' Association voted it the best crime novel ever.[7] It is one of Christie's best-known[8][9] and most controversial novels,[10][11][12] its innovative twist ending having a significant impact on the genre. Howard Haycraft included it in his list of the most influential crime novels ever written.[13]

Plot

[edit]Dr James Sheppard, the story's narrator, lives with his unmarried sister, Caroline, in the English country village of King’s Abbot. Telling the story in his own words, Dr Sheppard recounts being called to certify the death of a wealthy widow, Mrs Ferrars, who has committed suicide a year after her abusive husband's demise. Caroline speculates that Mrs Ferrars had poisoned her husband and has committed suicide out of remorse.

Roger Ackroyd, wealthy widower and owner of Fernly Park, tells Dr Sheppard that he needs to talk to him urgently and invites him to dinner that evening. In addition to Dr Sheppard, the dinner guests include Major Blunt, Ackroyd's sister-in-law Mrs Cecil Ackroyd, her daughter Flora, and Ackroyd's personal secretary, Geoffrey Raymond. Flora tells the doctor that she is engaged to Ralph Paton, Ackroyd's stepson, though the engagement is being kept confidential.

In his study after dinner, Ackroyd tells Dr Sheppard that he had been engaged to Mrs Ferrars for several months, and that she had admitted the day before that she had indeed poisoned her husband. She was being blackmailed, and promised to reveal the blackmailer's name within 24 hours. At this point Ackroyd's butler, Parker, enters with a letter that Mrs Ferrars had posted just before she killed herself. Ackroyd apologetically asks Dr Sheppard to leave so that he can read it alone.

Shortly after arriving back home, the doctor receives a phone call. Dr Sheppard tells Caroline that Ackroyd has been found dead and then returns to Fenly Park. Parker professes to know nothing about the phone call. Unable to get a response at the study door, Sheppard and Parker break it down and find Ackroyd dead in his chair, killed with his own dagger. The letter is missing and footprints are found leading in and out of the study through an open window.

Ralph disappears and becomes the primary suspect when the footprints are found to match shoes that he owns. Flora, convinced that Ralph is innocent, asks the recently retired detective Hercule Poirot to investigate. He agrees and visits the scene of the crime, asking Dr Sheppard to accompany him.

Parker notes to Poirot that a chair in Ackroyd's study has been moved. Poirot questions the guests and staff, including Ursula Bourne, the parlourmaid, who has no alibi. The window of opportunity for the murderer after Dr Sheppard's departure appears to have been quite short since Raymond and Blunt later heard Ackroyd talking in his study, and Flora says she saw him just before going up to bed.

Poirot unravels a complex web of intrigue, and presents the missing Ralph Paton – who was, it transpires, already secretly married to Ursula when Ackroyd had decided that he should marry Flora. The pair had arranged a clandestine meeting in the garden. Flora is forced to admit she never in fact saw her uncle after dinner, leaving Raymond and Blunt as the last people to hear Ackroyd alive. Blunt confesses his love for Flora.

Alone with Dr Sheppard, Poirot reveals he knows that Dr Sheppard himself is both Ferrars' blackmailer and Ackroyd's killer. Realising that Mrs Ferrars's letter would implicate him, Sheppard had stabbed Ackroyd before leaving the study. He left publicly through the front door, then put Ralph's shoes on, ran round to the study window and climbed back in. Locking the door from the inside, he set a desk dictaphone going, playing a recording of Ackroyd's voice, and pulled out a chair to hide it from the sightline of anyone standing in the doorway. To provide the excuse for returning to Fernly Park, he had asked a patient to call him at home. While Sheppard had the study to himself for a few minutes after the crime was discovered, he slipped the dictaphone into his medical bag, and put the chair back in place.

Poirot tells Sheppard that this will be reported to the police in the morning, and he suggests that to spare his sister Caroline the doctor might take his own life. Dr Sheppard finishes writing his report on Poirot's investigation (the novel itself), with his last chapter – Apologia – serving as his suicide note.

Principal characters

[edit]- Hercule Poirot – retired private detective, living in the village

- Dr James Sheppard – the local doctor, Poirot's assistant in his investigations, and the novel's narrator

- Caroline Sheppard – Dr Sheppard's unmarried sister

- Roger Ackroyd – the victim of the case. A wealthy businessman and widower

- Mrs Ferrars – widow who commits suicide at the start of the novel

- Mrs Cecil Ackroyd – widow of Roger's brother Cecil

- Flora Ackroyd – Ackroyd's niece, Cecil's daughter

- Captain Ralph Paton – Ackroyd's stepson from his late wife's previous marriage

- Major Hector Blunt – Ackroyd's friend, a guest of the household

- Geoffrey Raymond – Ackroyd's personal secretary

- John Parker – Ackroyd's butler

- Elizabeth Russell – Ackroyd's housekeeper

- Charles Kent – Russell's illegitimate son

- Ursula Bourne – Ackroyd's parlourmaid

- Inspector Davis – local police inspector for King's Abbot

- Inspector Raglan – police Inspector

- Colonel Melrose – Chief constable for the county

Narrative voice and structure

[edit]The novel is narrated by Dr James Sheppard, who becomes Poirot's assistant, in place of Captain Hastings who has married and settled in the Argentine. It includes an unexpected plot twist towards the end, when Dr Sheppard reveals he has throughout been an unreliable narrator, using literary techniques to conceal his guilt without writing anything untrue (e.g., "I did what little had to be done" at the point where he slipped the dictaphone into his bag and moved the chair).

Literary significance and reception

[edit]The review in the Times Literary Supplement began, "This is a well-written detective story of which the only criticism might perhaps be that there are too many curious incidents not really connected with the crime which have to be elucidated before the true criminal can be discovered". The review concluded, "It is all very puzzling, but the great Hercule Poirot, a retired Belgian detective, solves the mystery. It may safely be asserted that very few readers will do so."[10]

A long review in The New York Times Book Review, read in part:

There are doubtless many detective stories more exciting and blood-curdling than The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, but this reviewer has recently read very few which provide greater analytical stimulation. This story, though it is inferior to them at their best, is in the tradition of Poe's analytical tales and the Sherlock Holmes stories. The author does not devote her talents to the creation of thrills and shocks, but to the orderly solution of a single murder, conventional at that, instead.... Miss Christie is not only an expert technician and a remarkably good story-teller, but she knows, as well, just the right number of hints to offer as to the real murderer. In the present case his identity is made all the more baffling through the author's technical cleverness in selecting the part he is to play in the story; and yet her non-committal characterization of him makes it a perfectly fair procedure. The experienced reader will probably spot him, but it is safe to say that he will often have his doubts as the story unfolds itself.[11]

The Observer had high praise for the novel, especially the character Caroline:

No one is more adroit than Miss Christie in the manipulation of false clues and irrelevances and red herrings; and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd makes breathless reading from first to the unexpected last. It is unfortunate that in two important points – the nature of the solution and the use of the telephone – Miss Christie has been anticipated by another recent novel: the truth is that this particular field is getting so well ploughed that it is hard to find a virgin patch anywhere. But Miss Christie's story is distinguished from most of its class by its coherence, its reasonableness, and the fact that the characters live and move and have their being: the gossip-loving Caroline would be an acquisition to any novel.[4]

The Scotsman found the plot to be clever and original:

When in the last dozen pages of Miss Christie's detective novel, the answer comes to the question, "Who killed Roger Ackroyd?" the reader will feel that he has been fairly, or unfairly, sold up. Up till then he has been kept balancing in his mind from chapter to chapter the probabilities for or against the eight or nine persons at whom suspicion points.... Everybody in the story appears to have a secret of his or her own hidden up the sleeve, the production of which is imperative in fitting into place the pieces in the jigsaw puzzle; and in the end it turns out that the Doctor himself is responsible for the largest bit of reticence. The tale may be recommended as one of the cleverest and most original of its kind.[5]

Howard Haycraft,[14] in his 1941 work, Murder for Pleasure, included the novel in his "cornerstones" list of the most influential crime novels ever written.[13]

The English crime writer and critic Robert Barnard, in A Talent to Deceive: An appreciation of Agatha Christie, wrote that this novel is "Apart—and it is an enormous 'apart'—from the sensational solution, this is a fairly conventional Christie." He concluded that this is "A classic, but there are some better [novels by] Christie."[6]

John Goddard wrote an analysis of whether Christie 'cheats' with her sensational solution and concluded that the charge of cheating fails.[12]

In a biography of Christie, Laura Thompson wrote that this is the ultimate detective novel:

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is the supreme, the ultimate detective novel. It rests upon the most elegant of all twists, the narrator who is revealed to be the murderer. This twist is not merely a function of plot: it puts the whole concept of detective fiction on an armature and sculpts it into a dazzling new shape. It was not an entirely new idea ... nor was it entirely her own idea ... but here, she realised, was an idea worth having. And only she could have pulled it off so completely. Only she had the requisite control, the willingness to absent herself from the authorial scene and let her plot shine clear.[15]: 155–156

In 1944–1946, the American literary critic Edmund Wilson attacked the entire mystery genre in a set of three columns in The New Yorker. The second, in the 20 January 1945 issue, was titled "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?", though he does no analysis of the novel. He dislikes mystery stories altogether, and chose the famous novel as the title of his piece.[16][17]

In 1990, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd came in at fifth place in The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time, a ranking by the members (all crime writers) of the Crime Writers' Association in Britain.[8] A similar ranking was made in 1995 by the Mystery Writers of America, putting this novel in twelfth place.[9]

Literature professor and author Pierre Bayard, in the 1998 work Qui a tué Roger Ackroyd? (Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?), re-investigates Agatha Christie's Ackroyd, proposing an alternative solution in another crime novel. He argues in favour of a different murderer – Sheppard's sister, Caroline – and says Christie subconsciously knew who the real culprit is.[18][19]

In 1999 the novel was included in Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century published in the French newspaper Le Monde, chosen by readers from a list of 200.[20]

In 2013, the Crime Writers' Association voted this novel as CWA Best Ever Novel.[7] The 600 members of CWA said it was "the finest example of the genre ever penned." It is a cornerstone of crime fiction, which "contains one of the most celebrated plot twists in crime writing history."[7][21] The poll taken on the 60th anniversary of CWA also honoured Agatha Christie as the best crime novel author ever.[7][21]

In the "Binge!" article of Entertainment Weekly Issue #1343–44 (26 December 2014 – 3 January 2015), the writers picked The Murder of Roger Ackroyd as an "EW and Christie favorite" on the list of the "Nine Great Christie Novels".[22]

The character of Caroline Sheppard was later acknowledged by Christie as a possible precursor to her famous detective Miss Marple.[23]: 433

Development

[edit]Christie revealed in her 1977 autobiography that the basic idea of the novel was given to her by her brother-in-law, James Watts of Abney Hall, who suggested a novel in which the criminal would be a Dr Watson character, which Christie considered to be a "remarkably original thought".[23]: 342

In March 1924 Christie also received an unsolicited letter from Lord Louis Mountbatten. He had been impressed with her previous works and wrote, courtesy of The Sketch magazine (publishers of many of her short stories at that time) with an idea and notes for a story whose basic premise mirrored the Watts suggestion.[15]: 500 Christie acknowledged the letter and after some thought, began to write the book but to a plot line of her invention. She also acknowledged taking inspiration from the infamous case of the unsolved death of Charles Bravo, who she thought had been murdered by Dr James Manby Gully.[24]

In December 1969 Mountbatten wrote to Christie again after having seen a performance of The Mousetrap. He mentioned his letter of the 1920s, and Christie replied, acknowledging the part he played in the conception of the book.[25]: 120–121

Publication history

[edit]The story first appeared as a fifty-four part serialisation in the London Evening News from Thursday, 16 July, to Wednesday, 16 September 1925 under the title Who Killed Ackroyd? In the United States, the story was serialised in four parts in Flynn's Detective Weekly from 19 June (Volume 16, Number 2) to 10 July 1926 (Volume 16, Number 5). The text was heavily abridged and each instalment carried an uncredited illustration.

The Collins first edition of June 1926 (retailing for seven shillings and sixpence)[2] was Christie's first work placed with that publisher. "The first book that Agatha wrote for Collins was the one that changed her reputation forever; no doubt she knew, as through 1925 she turned the idea over in her mind, that here she had a winner."[15]: 155 The first United States publisher was The Dodd Mead and Company (New York), 19 June 1926 (retailing at $2.00).[3]

By 1928, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was available in braille through the UK's Royal National Institute for the Blind[26] and was among the first works to be chosen for transfer to Gramophone record for their Books for the Blind[broken anchor] library in the autumn of 1935.[27][28] By 1936 it was listed as one of only eight books available in this form.[29]

Book dedication

[edit]Christie's dedication in the book reads "To Punkie, who likes an orthodox detective story, murder, inquest, and suspicion falling on every one in turn!"

"Punkie" was the family nickname of Christie's sister and eldest sibling, Margaret ("Madge") Frary Watts (1879–1950). Despite their eleven-year age gap, the sisters remained close throughout their lives. Christie's mother first suggested to her that she should alleviate the boredom of an illness by writing a story. But soon after, when the sisters had been discussing the recently published classic detective story by Gaston Leroux, The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1908), Christie said she would like to try writing such a story. Margaret challenged her, saying that she would not be able to do it.[15]: 102 In 1916, eight years later, Christie remembered this conversation and was inspired to write her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles.[25]: 77

Margaret Watts wrote a play, The Claimant, based on the Tichborne Case, which enjoyed a short run in the West End at the Queen's Theatre from 11 September to 18 October 1924, two years before the book publication of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.[25]: 113–115

Dustjacket blurb

[edit]The dustjacket blurb read as follows:

M. Poirot, the hero of The Mysterious Affair at Stiles [sic] and other brilliant pieces of detective deduction, comes out of his temporary retirement like a giant refreshed, to undertake the investigation of a peculiarly brutal and mysterious murder. Geniuses like Sherlock Holmes often find a use for faithful mediocrities like Dr Watson, and by a coincidence it is the local doctor who follows Poirot round, and himself tells the story. Furthermore, as seldom happens in these cases, he is instrumental in giving Poirot one of the most valuable clues to the mystery.[30]

In popular culture

[edit]- Gilbert Adair's 2006 locked-room mystery The Act of Roger Murgatroyd was written as "a celebration-cum-critique-cum-parody" of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.[31]

Adaptations

[edit]Stage play

[edit]Alibi (play)

The book formed the basis of the earliest adaptation of any work of Christie's when the play, Alibi, adapted by Michael Morton, opened at the Prince of Wales Theatre in London on 15 May 1928. It ran for 250 performances with Charles Laughton as Poirot. Laughton also starred in the Broadway run of the play, retitled The Fatal Alibi, which opened at the Booth Theatre on 8 February 1932. The American production was not as successful and closed after just 24 performances. Alibi inspired Christie to write her first stage play, Black Coffee. Christie, with her dog Peter, attended the rehearsals of Alibi and found its "novelty" enjoyable.[15]: 277 However, "she was sufficiently irritated by the changes to the original to want to write a play of her own."[15]: 277

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (play)

In 2023, the novel was adapted for the stage by Edgar award nominated playwright Mark Shanahan[32] in partnership with Agatha Christie, Ltd.[33] The play received its first public reading at the Westport Country Playhouse in June 2023 with Santino Fontana as Dr. Sheppard and Arnie Burton as Poirot.[34] Shortly thereafter, the world premiere production directed by Mark Shanahan opened at the TONY Award winning Alley Theatre in Houston, TX[35] and featured the Alley's resident company of actors with David Sinaiko as Poirot. The Houston Chronicle reviewed the play, calling it "a whodunnit done right. This world premiere adaptation elegantly transfers Christie’s rich mystery from the page to the stage..."[36] The play opened on 21 July and ran through 27 August in a limited run as part of the Alley Theatre's Summer Chills series[37] and was subsequently published by Concord Theatricals[38] before receiving numerous productions. The adaptation remains mostly faithful to the book, with Shanahan stating that crafting the adaptation was a "labour of love."[39]

Film

[edit]The play was turned into the first sound film based on a Christie work. Running 75 minutes, it was released on 28 April 1931, by Twickenham Film Studios and produced by Julius S. Hagan. Austin Trevor played Poirot, a role he reprised later that year in the film adaptation of Christie's 1930 play, Black Coffee. Alibi is considered to be a lost film.

Radio

[edit]Orson Welles adapted the novel as a one-hour radio play for the 12 November 1939 episode of The Campbell Playhouse. Welles played both Dr Sheppard and Hercule Poirot. The play was adapted by Herman J. Mankiewicz,[40]: 355 [41] produced by Welles and John Houseman, and directed by Welles.

Cast:

Orson Welles as Hercule Poirot and Dr Sheppard

Edna May Oliver as Caroline Sheppard

Alan Napier as Roger Ackroyd

Brenda Forbes as Mrs Ackroyd

Mary Taylor as Flora

George Coulouris as Inspector Hamstead

Ray Collins as Mr Raymond

Everett Sloane as Parker

The novel was also adapted as a 1½-hour radio play for BBC Radio 4 first broadcast on 24 December 1987. John Moffatt made the first of his many performances as Poirot. The adaptation was broadcast at 7.45pm and was recorded on 2 November of the same year; it was adapted by Michael Bakewell and produced by Enyd Williams.

Cast:

John Moffatt as Hercule Poirot

John Woodvine as Doctor Sheppard

Laurence Payne as Roger Ackroyd

Diana Olsson as Caroline Sheppard

Eva Stuart as Miss Russell

Peter Gilmore as Raymond

Zelah Clarke as Flora

Simon Cuff as Inspector Davis

Deryck Guyler as Parker

With Richard Tate, Alan Dudley, Joan Matheson, David Goodland, Peter Craze, Karen Archer and Paul Sirr

Television

[edit]The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was adapted as a 103-minute drama transmitted in the UK on ITV Sunday 2 January 2000, as a special episode in their series, Agatha Christie's Poirot.[42]

Adaptor: Clive Exton

Director: Andrew Grieve

Cast:

David Suchet as Hercule Poirot

Philip Jackson as Chief Inspector Japp

Oliver Ford Davies as Dr Sheppard

Selina Cadell as Caroline Sheppard

Roger Frost as Parker

Malcolm Terris as Roger Ackroyd

Nigel Cooke as Geoffrey Raymond

Daisy Beaumont as Ursula Bourne

Flora Montgomery as Flora Ackroyd

Vivien Heilbron as Mrs Ackroyd

Gregor Truter as Inspector Davis

Jamie Bamber as Ralph Paton

Charles Early as Constable Jones

Rosalind Bailey as Mrs Ferrars

Charles Simon as Hammond

Graham Chinn as Landlord

Clive Brunt as Naval petty officer

Alice Hart as Mary

Philip Wrigley as Postman

Phil Atkinson as Ted

Elizabeth Kettle as Mrs Folliott

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was adapted as a 190-minute drama transmitted in Japan on Fuji Television on 14 April 2018, as a special drama, under the title "The Murder of Kuroido" (Japanese: 黒井戸殺し, Kuroido Goroshi).[43]

Adaptor: Koki Mitani

Director: Hidenori Joho

Cast:

Mansai Nomura as Takeru Suguro, based on Hercule Poirot

Yo Oizumi as Heisuke Shiba, based on James Sheppard

Yuki Saito as Kana Shiba, based on Caroline Sheppard

Takashi Fujii as Jiro Hakamada, based on John Parker

Kenichi Endō as Rokusuke Kuroido, based on Roger Ackroyd

Mayu Matsuoka as Hanako Kuroido, based on Flora Ackroyd

Tamiyo Kusakari as Mitsuru Kuroido, based on Cecil Ackroyd

Osamu Mukai as Haruo Hyodo, based on Ralph Paton

Yasufumi Terawaki as Moichi Reizei, based on Geoffrey Raymond

Tomohiko Imai as Goro Rando, based on Hector Blunt

Kimiko Yo as Tsuneko Raisen, based on Elizabeth Russell

Sayaka Akimoto as Asuka Honda, based on Ursula Bourne

Jiro Sato as Koshiro Sodetake, based on Inspector Raglan

Yo Yoshida as Sanako Karatsu, based on Mrs Ferrars

Kazuyuki Asano as Hamose, based on Mr Hammond

Masato Wada as Kenzo Chagawa, based on Charles Kent

Graphic novel

[edit]The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was released by HarperCollins as a graphic novel adaptation on 20 August 2007, adapted and illustrated by Bruno Lachard (ISBN 0-00-725061-4). This was translated from the edition first published in France by Emmanuel Proust éditions in 2004 under the title, Le Meurtre de Roger Ackroyd.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "British Library Item details". primocat.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ a b The English Catalogue of Books. Vol. XII, A–L. Kraus Reprint Corporation. 1979. p. 317.

- ^ a b Marcum, J S (May 2007). "The Classic Years 1920s". An American Tribute to Agatha Christie. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ a b "Review". The Observer. 30 May 1926. p. 10.

- ^ a b "Review". The Scotsman. 22 July 1926. p. 2.

- ^ a b Barnard, Robert (1990). A Talent to Deceive: An appreciation of Agatha Christie (Revised ed.). Fontana Books. p. 199. ISBN 0-00-637474-3.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Jonathan (5 November 2013). "Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd voted best crime novel ever". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ a b Moody, Susan, ed. (1990). The Hatchards Crime Companion. 100 Top Crime Novels Selected by the Crime Writers' Association. London. ISBN 0-904030-02-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Penzler, Otto (1995). Mickey Friedman (ed.). The Crown Crime Companion. The Top 100 Mystery Novels of All Time Selected by the Mystery Writers of America. New York. ISBN 0-517-88115-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Review". The Times Literary Supplement. 10 June 1926. p. 397.

- ^ a b "Review". The New York Times Book Review. 18 July 1926.

- ^ a b Goddard, John (2018). Agatha Christie's Golden Age: An Analysis of Poirot's Golden Age Puzzles. Stylish Eye Press. pp. 34–35, 95–101. ISBN 978-1-999612016.

- ^ a b Collins, R D, ed. (2004). "Haycraft Queen Cornerstones: Complete Checklist". Classic Crime Fiction. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ Grimes, William (13 November 1991). "Howard Haycraft Is Dead at 86; A Publisher and Mystery Scholar". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Thompson, Laura (2007). Agatha Christie, An English Mystery. Headline. ISBN 978-0-7553-1487-4.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (14 October 1944). "Why Do People Read Detective Stories?". Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (20 January 1945). "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?". Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ Bayard, Pierre (2002) [1998]. Qui a tué Roger Ackroyd?. Les Editions de Minuit. ISBN 978-2707318091.

- ^ Bayard, Pierre (2000). Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?. Fourth Estate New Press. ISBN 978-1565845794.

- ^ Savigneau, Joysane (15 October 1999). "Ecrivains et choix sentimentaux" [Authors and sentimental choices]. Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Agatha Christie whodunit tops crime novel poll". BBC News: Entertainment & Arts. 6 November 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ "Binge! Agatha Christie: Nine Great Christie Novels". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1343–44. 26 December 2014. pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Christie, Agatha (1977). An Autobiography. Collins. ISBN 0-00-216012-9.

- ^ Kinnell, Herbert G (14 December 2010). "Agatha Christies' Doctors". British Medical Journal. 341: c6438. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6438. PMID 21156735. S2CID 31367979. Archived from the original on 26 April 2024. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Morgan, Janet (1984). Agatha Christie, A Biography. Collins. ISBN 0-00-216330-6.

- ^ "A Book Printed For the Asking!". Evening Telegraph. 24 September 1928. Retrieved 24 July 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Talking Books". The Times. London. 20 August 1935. p. 15.

- ^ "Recorded books for the blind". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 23 August 1935. Retrieved 24 July 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Talking Books". The Times. London. 27 January 1936. p. 6.

- ^ Christie, Agatha (June 1926). The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. London: William Collins and Sons.

- ^ Adair, Gilbert (11 November 2006). "Unusual suspect: Gilbert Adair discovers the real secret of Agatha Christie's success". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Mystery Writers of America EdgarAwards.com". EdgarAwards.com. Mystery Writers of America.

- ^ "Cast & Creative Team Set for Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at Alley Theatre". broadway world.

- ^ "See Who's Joining Santino Fontana in Reading of Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd". Playbill.

- ^ "Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd". Playbill.

- ^ "Review: Agatha Christie mystery at Alley Theatre is a Whodunnit done right". Chron. Houston Chronicle.

- ^ "Adapted for the Stage and Directed by Mark Shanahan World Premiere Hubbard Theatre". alleytheatre.org. The Alley Theatre. 24 May 2023.

- ^ "The Murder of Roger Ackroyd | Concord Theatricals". concordtheatricals.com. Concord Theatricals.

- ^ "The Murder of Roger Ackroyd: Interview with Mark Shanahan". Agatha Christie Ltd. 3 August 2023.

- ^ Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter (1992). Rosenbaum, Jonathan (ed.). This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-016616-9.

- ^ "The Campbell Playhouse: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd". Orson Welles on the Air, 1938–1946. Indiana University Bloomington. 12 November 1939. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ "The murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie". The Booktrail. 18 December 2018. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "野村萬斎×大泉洋がバディに!アガサ・クリスティー「アクロイド殺し」を三谷幸喜脚本で映像化『黒井戸殺し』4月放送" [Mansai Nomura x Yo Oizumi becomes a buddy! Agatha Christie's "The Murder of Rogers" is visualized in the script by Koki Mitani "Kuroido Goroshi" broadcast in April]. TV LIFE (in Japanese). Gakken Plus. 15 February 2017. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Rowland, Susan (2001). From Agatha Christie to Ruth Rendell: British women writers in detective and crime fiction. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-67450-2.

External links

[edit] The full text of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at Wikisource

The full text of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at Wikisource- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at Project Gutenberg

- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at Standard Ebooks

- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at the HathiTrust Digital Library

- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at the official Agatha Christie website

- 1926 British novels

- Hercule Poirot novels

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- Novels first published in serial form

- Works originally published in The Evening News (London newspaper)

- William Collins, Sons books

- British novels adapted into films

- British novels adapted into television shows

- Fiction about mariticide

- First-person narrative novels

- Lord Mountbatten