Kid Miracleman

| Kid Miracleman | |

|---|---|

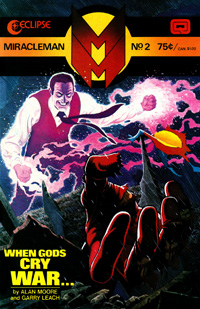

Kid Miracleman on the cover of Miracleman #2, by Garry Leach. | |

| Character information | |

| First appearance | Marvelman #102 (1955) |

| Created by | Mick Anglo |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Jonathan James "Johnny" Bates |

| Species | Human |

| Place of origin | Earth |

| Team affiliations | Miracleman Family (1955-1963)[Note 1] |

| Partnerships | Miracleman[Note 1] Young Miracleman[Note 1] |

| Notable aliases | The Adversary |

| Abilities | Initially flight, strength, & durability via forcefield; later mind control, electrical abilities & optic blasts |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher |

|

| Genre | |

| Publication date | July 30 1955 |

Kid Miracleman (originally Kid Marvelman),[Note 1] whose civilian name is Jonathan James "Johnny" Bates, is a fictional British Golden Age comic book character, originally created by Mick Anglo for publisher L. Miller & Son in 1955, and debuting in Marvelman #102, dated July 10 of that year.

The character was subsequently revived in 1982 by Alan Moore as an antagonist in Marvelman, published in the pages of the anthology Warrior. The series was continued from 1985 as Miracleman, with the character renamed Kid Miracleman as a result.

Creation

[edit]By 1955 Mick Anglo had been producing the successful Marvelman and Young Marvelman comics for London publisher L. Miller & Son for around 18 months, inspired by the Fawcett Publications Captain Marvel and Captain Marvel Jr characters. While the third member of Fawcett's Marvel Family was Mary Marvel, Anglo instead opted to make the a new male addition. Alan Moore[1] and Denis Gifford [2] would later speculate that the comic's audience was primarily prepubescent boys who would not react well to a female character.

Kid Marvelman debuted in the secondary strip of Marvelman #101, as the superhero identity of young boy Johnny Bates.[3] The appearance was written by Anglo and drawn by Don Lawrence, who would illustrate the majority of the character's 1950s appearances. After a stint as a supporting feature in Marvelman, the character was span off into the new monthly title Marvelman Family, where the lead strip saw Kid Marvelman team up with Marvelman and Young Marvelman against various threats. Like his stablemates, Kid Marvelman's adventures began with the character already having his powers; unlike them, his origin was never related to readers. Instead a text box in his first appearance noting that Bates had been "appointed by Marvelman himself" was the only explanation given for how the character has been empowered.[4]

A competitive market saw sales of the Marvelman comics decline, and in November 1959 Marvelman Family was cancelled,[3] shortly after Lawrence's departure following a disagreement with Anglo.[5] While his co-stars would appear in their own weekly comics until 1963, Kid Marvelman was rarely glimpsed within. The Marvelman Family name was briefly revived in 1963 for an annual – with Kid Marvelman on the cover along with his allies – but the contents featured only a single reprint appearance for the character.

Revival

[edit]When Marvelman was revived as a revisionist superhero strip in Quality Communications anthology Warrior, Kid Marvelman was part of the story's main cast. Writer Alan Moore reinvented the character as a villain, both of Marvelman and – in the early stages – the mooted shared 'Warrior universe'. The latter posited that another of Moore's strips for the magazine – V for Vendetta – took place in an alternate universe where Marvelman was never reborn;[6] Warrior publisher Dez Skinn joked that Kid Marvelman killed V during his rise to power in the 'mainstream' universe.[7] At the suggestion of artist Garry Leach, the character retained a business suit for his present day appearances, with the original yellow version largely being restricted to flashbacks. The artist based the character's updated design on musician David Bowie and actor Jon Finch.[8] Later, a predominantly black version was created.

Moore's original proposal for the series gave Bates' year of birth as 1949 and his mother as an RAF worker. It also noted that he was born out of wedlock – a considerable social stigma in post-war Britain – and was orphaned at the age of five. Further detail was also added on his activities in founding Sunburst Cybernetics, suggesting he used his abilities to conduct industrial espionage.[9] While these aspects are consistent with the published material they have yet to be referenced directly in the stories. After the Warrior strip entered hiatus following a disagreement between Moore and Leach's successor Alan Davis, Grant Morrison pitched a Kid Marvelman story featuring the character debating with a Catholic priest; however, Moore vetoed anyone else using the character.[7] The story would eventually see print in 2014 as part of Marvel Comics' All-New Miracleman Annual #1, with new art from Joe Quesada.[10] The series was continued from 1985 as Miracleman by Eclipse Comics in order to avoid legal action by Marvel Comics, with the character renamed Kid Miracleman as a result.[11]

Fictional character biography

[edit]Original

[edit]After being selected by Marvelman, tenement-dwelling schoolboy Johnny Bates gained the ability to change into Kid Marvelman by calling his hero's name. He fought crooks,[4] spy rings,[12] thieves'[13] and squabbling yokels.[14] He also frequently joined Marvelman and Young Marvelman as the super team known as the Marvelman Family; among the threats they faced were Garrer and his army of time-travelling renegades,[15] a combined alliance of Marvelman's arch-enemy Doctor Gargunza and his nephew, Young Marvelman rogue Young Gargunza,[16] the King of Vegetableland[17] invaders from the planet Vardica,[18] would-be dictator Professor Batts and his speech-scramber,[19] a crime boss intent on sinking Pacific City below the ocean,[20] the cruel, slave-driving King Snop of Atlantis (which the story revealed would eventually become Australia),[21] an attempt by Gargunza to declare himself King of the Universe,[22] cruel 14th century knight Simon de Carton (and clearing the name of Amadis of Gaul in the process),[23] a monster accidentally collected from the planet Droon[24] and Professor Wosmine's shrinking ray.[25]

Revival

[edit]Being orphaned and related to RAF staff, Jonathan "Johnny" Bates' name found its way onto a list of potential candidates for Spookshow's Project Zarathustra. He was selected at random and abducted in 1956 (aged between 6 and 7) to be the third member of the Miracleman Family, a superhuman British Cold War weapons project. As with the previous recruits – Michael Moran and Richard Dauntless – he was kept unconscious while captured Qys technology was used to grow a superpowered clone version that was placed in infraspace.[26] The project's inventor, Doctor Emil Gargunza, used a complex series of induced dreams that kept the superhumans docile and suggestible, making all three believe they were superheroes fighting evil.[27][28] Using his change-word 'Miracleman' allowed him to switch forms, and his superhuman body could fly, had super-strength and invulnerability via a forcefield.[29][30]

Unknown to the project head Sir Dennis Archer, Gargunza planned to use the superhumans to produce a new body for himself, and was diverting funds from Zarathustra to a secondary lab. When Archer came close to discovering this, Gargunza fled to Paraguay.[31][32] Worried that the Miracleman Family would be impossible to control, Archer planned Operation Dragonslayer. This consisted of luring the trio out of Earth's atmosphere to what they believed was a new space station made by a fictional analogue of Gargunza the scientist had inserted into the dreams, however this was actually a nuclear bomb cloaked by holograms. Archer believed the resulting explosion destroyed the Miracleman Family.[33]

However, Kid Miracleman had survived. Bates would later tell Moran he had felt unsettled and instinctively dived away from Dragonslayer, suffering burns and broken bones – though he also claimed he had lost his powers at the same time. However, he had not – and at age 13 decided to remain in the superhuman form of Kid Miracleman, but using Bates' name. As the most powerful person in the world he grew corrupted, developing disdain for human life. To build power and wealth he set up Sunburst Cybernetics in 1970 and rapidly turned it into a huge success.[34] His plans were jeopardised by Moran unexpectedly remembering his own change-word and reappearing at Larksmere in 1982.[35] To judge how much of a threat he represented, Kid Miracleman invited Mike and his wife Liz to visit Sunburst. Initially he was able to convince the Morans he had lost his powers but Mike detected his former friend was attempting to control his mind and correctly guessed he was lying, and still a superhuman. Mike forced Kid Miracleman to reveal this by pushing him off the balcony,[34] and after witnessing him murder his secretary without compunction called up Miracleman to fight him.[36] The pair battled in the Docklands and Brixton. Thanks to his far greater experience as a superhuman, Kid Miracleman was able to twice trounce his former mentor, having gained the ability to fire incinerating beams from his eyes and electrically charge clouds. However, when gloating he accidentally said his own name, transforming him back into a dazed 13-year old Johnny Bates.[37]

Bates is taken into care at St. Crispin's Hospital, where he was initially catatonic by his own volition in an attempt to keep Kid Miracleman at bay.[38][39] Kid Miracleman however is powerful enough to evade detection by Qys agents by hiding in Bates' mind[40] and was able to goad Bates into waking and joining other children in the facility.[41] Small, awkward and with little experience of the present day, Bates was targeted by bullies.[42][43] He attempted to tell a kind nurse named Trish of the existence of Kid Miracleman but was unable to do so; Bates refused to give in and unleash the increasingly unhinged Kid Miracleman in the face of their insults and beatings[32] until 17 August 1985. When one of his tormentors rapes him Johnny finally releases Kid Miracleman.[44] After killing the attackers and – after a brief hesitation – Trish – he devastates London, butchering thousands largely to pass the time until he is noticed by Miracleman and his allies. When they arrive Kid Miracleman shows little interest in who Miraclewoman, Huey Moon or the Warpsmiths are and simply attacks. Aza Chorn warps the Bank of England and then Marble Arch onto him but he easily breaks out and viciously defeats Miraclewoman. Moon attempts to keep him busy while Chorn arranges extra power for Miracleman, but even with this done Kid Miracleman's sheer ferocity makes him almost impossible to match. However, Chorn hits on the idea of warping debris inside Kid Miracleman's forcefield, grievously injuring the adversary before being killed himself. The unbearable pain causes Kid Miracleman to splutter his change-word, switching places back to the traumatised, tearful Johnny Bates. He begs Miracleman to find a way of stopping Kid Miracleman from returning and Miracleman regretfully obliges by destroying the boy's head.[45]

While still alive, Kid Miracleman is left trapped dormant in infra-space.[46] His actions lead to a huge upheaval after his death; their presence no longer a secret, Miracleman and his allies forge Earth into a utopia. Kid Miracleman himself is remembered by a nihilistic subculture known as the Bates, many of whom imitate him in manner and look[47] – something that unsettles even Miracleman.[48] In addition to the Bates movement, his actions also see the word "kid" and derivatives such as "kidding" become used as an expletive. Johnny Bates' headless corpse features prominently in the Stanley Kubrick documentary Veneer, an assemblage of footage taken during the aftermath of Kid Miracleman's massacre,[49] though it is not immediately clear to viewers who he is.[50] A carnival of remembrance is held in cities across the world every 17 August, known as London Day, while the remains of many of his victims are preserved as a memorial.[51]

Following Young Miracleman's resurrection in 2001 he learns of his former friend's crimes.[52] As he becomes more disillusioned with Miracleman's utopia and his actions, Young Miracleman begins to experience taunting visions of Kid Miracleman, similar to those experienced by Johnny Bates.[53][54]

Powers and abilities

[edit]As Kid Miracleman, Bates initially has the ability to fly, combined with superhuman strength an invulnerability roughly equal to those of Miracleman and Young Miracleman.[29] During Project Zarathustra field tests, Kid Miracleman was capable of easily out-pacing the fastest military jets of the period, and flying through a solid titanium bunker without effort.[27] He is fast enough to reach a distance from the explosion of the Project Dragonslayer nuclear device where it causes him no lasting harm; a witness to his survival recalls him being on fire but still mobile. After deciding to take over the identity of Johnny Bates he rapidly begins to gain extra abilities. By October 1966 he is able to project incinerating beams from his eyes capable of reducing a human to a skeleton in seconds. He uses his advanced brain to rapidly build up a business and is even able to control the minds of humans in order to allay suspicions, though the latter ability is not flawless and is detected by Mike Moran. Kid Miracleman is also capable of agitating the ions in storm clouds so they can discharge lightning. Kid Miracleman's abilities are amplified by his total lack of restraint and contempt for all other forms of life.

Reception

[edit]Writing for Amazing Heroes in 1986, N.A. Collins listed Kid Miracleman as one of "The Ten Best Super-Hero Sidekicks", noting the "concept of a litte boy who enjoys pulling the wings off of flies coupled with the ability to shift continents is pretty damn scary."[55] In the same publication, following the events of Miracleman #15 Mike Maddox described the character as "perhaps the nastiest ever super-human".[56] In 2006, Wizard Magazine ranked Kid Marvelman 52nd in their "Top 100 Greatest Villains Ever" list.[57] Three years later IGN placed the character 26th in their "Top 100 Comic Book Villains of All Time" list.[58] Mark Ginocchio of ComicBook.com rated Kid Miracleman turning against Miracleman as #6 on a list of 10 Great Comic Book Heel Turns in 2014, saying "Kid Miracleman's heel turn is notable for just how extreme of a character shift it ended up being".[59] In a 2016 essay on the so-called 'Dark Age of Comic Books' for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Jackson Ayres noted the "extreme and appalling" destruction of London by Kid Miracleman.[60] The character has been cited as an influence on wider superhero media - Christian Holub of Entertainment Weekly noted the influence of Miracleman in general and Kid Miracleman's arc in particular on the 2019 superhero film Brightburn.[61] while Timothy Donohoo of Comic Book Resources drew a number of comparisons between the comics and Superman film Man of Steel.[62]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Since licensing the characters from Mick Anglo in 2009, Marvel Comics have used the Kid Marvelman name for original 1956-1959 appearances and Kid Miracleman for revival material.

References

[edit]- ^ Moore, Alan (w). "M*****man: Full Story and Pics" Miracleman, no. 2 (October 1985). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Gifford, Denis (w). "Founding a Family" Miracleman Family, no. 2 (September 1988). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ a b Wilson, Derek (w). "The Marvelman Story" Marvelman Classic, no. Volume 1 (19 January 2017). Marvel Comics.

- ^ a b "Introducing Kid Marvelman" Marvelman, no. 102 (30 July 1955). L. Miller & Son.

- ^ Khoury, George (8 May 2024). True Brit: A Celebration of the Great Comic Book Artists of the UK. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781893905337.

- ^ Khoury, George (2001). "A Chronology of Everything (almost)". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ a b Khoury, George (2001). "Reign of the Warrior King". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ Khoury, George (2001). "The Architect of Miracleman". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ Khoury, George (2001). "Alan Moore's Original Proposal". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ "Marvel Announces New "Miracleman" from Morrison, Quesada, Milligan & Allred". Comic Book Resources. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Khoury, George (2001). "Miracleman Index". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ "Kid Marvelman and the Wild Man of Borneo" Marvelman, no. 105 (20 August 1955). L. Miller & Son.

- ^ "Kid Marvelman and the Park Thefts" Marvelman, no. 107 (3 September 1955). L. Miller & Son.

- ^ "Kid Marvelman and the Bad-Tempered Farmer" Marvelman, no. 108 (10 September 1955). L. Miller & Son.

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the Invaders from the Future" Marvelman Family, no. 1 (October 1956). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the Shadow Stealers" Marvelman Family, no. 2 (November 1956). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the Giant Marrow" Marvelman Family, no. 4 (February 1957). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the Hollow Planet" Marvelman Family, no. 4 (March 1957). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the Speech Scrambler" Marvelman Family, no. 8 (July 1957). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the City Under the Sea" Marvelman Family, no. 9 (August 1957). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the Atlantis Fable" Marvelman Family, no. 10 (September 1957). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and King Gargunza" Marvelman Family, no. 14 (March 1958). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Marvelman Family and the City Under the Sea" Marvelman Family, no. 18 (July 1958). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Light, Norman (a). "The Mighty Marvelman Family and the Dragons of Great Droon" Marvelman Family, no. 29 (August 1959). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Anglo, Mick (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "The Mighty Marvelman Family and 'Jungle Fury'" Marvelman Family, no. 30 (August 1957). L. Miller & Son, Ltd..

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Davis, Alan (a). "I Heard Woodrow Wilson's Guns..." Warrior, no. 18 (April 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b Moore, Alan (w), Davis, Alan (a). "Zarathustra" Warrior, no. 11 (July 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Ridgway, John (a). "The Red King Syndrome" Warrior, no. 17 (January 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b Anglo, Mick; Moore, Alan (w), Lawrence, Don (a). "Prologue - 1956" Miracleman, no. 1 (August 1985). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Davis, Alan (a). "Saturday Morning Pictures" Marvelman Special, no. 1 (Summer 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Davis, Alan (a). "A Little Piece of Heaven" Warrior, no. 20 (July 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b Moore, Alan (w), Totleben, John (a). "Aphrodite" Miracleman, no. 12 (September 1987). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Leach, Garry (a). "...a Dream of Flying" Warrior, no. 1 (March 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b Moore, Alan (w), Leach, Garry (a). "When Johnny Comes Marching Home..." Warrior, no. 3 (July 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Leach, Garry (a). "(Untitled)" Warrior, no. 2 (April 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Leach, Garry (a). "Dragons" Warrior, no. 5 (September 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Davis, Alan; Leach, Garry (a). "Fallen Angels, Forgotten Thunder" Warrior, no. 6 (October 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Davis, Alan (a). "Catgames" Warrior, no. 13 (September 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Davis, Alan (a). "Nightmares" Warrior, no. 15 (November 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Veitch, Rick (a). "Scenes from the Nativity" Miracleman, no. 9 (July 1986). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Veitch, Rick (a). "Mindgames" Miracleman, no. 10 (December 1986). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Totleben, John (a). "Chronos" Miracleman, no. 11 (May 1987). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Totleben, John (a). "Hermes" Miracleman, no. 13 (November 1987). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Totleben, John (a). "Pantheon" Miracleman, no. 14 (April 1988). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Totleben, John (a). "Nemesis" Miracleman, no. 15 (November 1988). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "Retrieval" Miracleman, no. 17-22 (June 1990-August 1991). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "Trends" Miracleman, no. 18 (August 1990). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Totleben, John (a). "Olympus" Miracleman, no. 16 (December 1989). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "Screaming" Total Eclipse, no. 4 (January 1989). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "When Titans Clash!" Miracleman by Gaiman & Buckingham: The Silver Age, no. 2 (January 2023). Marvel Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "Carnival" Miracleman, no. 22 (August 1991). Eclipse Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "The Secret Origin of Young Miracleman" Miracleman by Gaiman & Buckingham: The Silver Age, no. 1 (December 2022). Marvel Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "Trapped... in a World He Never Made!" Miracleman by Gaiman & Buckingham: The Silver Age, no. 3 (February 2023). Marvel Comics.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (w), Buckingham, Mark (a). "An Alien Walks Among Us" Miracleman by Gaiman & Buckingham: The Silver Age, no. 4 (March 2023). Marvel Comics.

- ^ Collins, N.A. (1 September 1986). "X of a Kind - The Ten Best Super-Hero Sidekicks". Amazing Heroes. No. 102. Fantagraphics.

- ^ Maddox, Mike (15 March 1989). "Perspective". Amazing Heroes. No. 161. Fantagraphics.

- ^ Wizard, #177, July 2006

- ^ The Top 100 Comic Book Villains - IGN.com

- ^ "Breaking Bad: 10 Great Comic Book Heel Turns". ComicBook.com.

- ^ "When Were Superheroes Grim and Gritty?". Los Angeles Review of Books. 20 February 2016.

- ^ "How Brightburn connects to one of the best superhero comics ever". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "Marvel's 'Newest' Superhero May Have Inspired… the DCEU?". Comic Book Resources. January 2022.

- Comics characters

- Comics characters introduced in 1955

- 1955 comics debuts

- Superhero comics

- Eclipse Comics superheroes

- Marvel Comics characters who can move at superhuman speeds

- Marvel Comics characters with superhuman strength

- Marvel Comics male superheroes

- Marvel Comics male supervillains

- Miracleman

- Fictional mass murderers