Kennecott, Alaska

Kennecott Mines | |

Alaska Heritage Resources Survey

| |

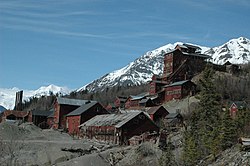

The 14-story Kennicott Concentration Mill (to the right). The mines are 5 miles up in the mountains to the east/northeast. Also pictured: foreground (left to right): power plant, machine shop, flotation plant, ammonia leaching plant (world's first); in the trees to the right - general manager's office (the log cabin portion was the first building built in Kennicott) | |

| Location | East of Kennicott Glacier, about 6.5 miles (10.5 km) north of McCarthy |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | McCarthy, Alaska |

| Coordinates | 61°31′09″N 142°50′29″W / 61.51909°N 142.84149°W |

| Area | 7,700 acres (3,100 ha) |

| Built | 1908-1911 |

| Architect | Kennecott Mines Company |

| NRHP reference No. | 78003420 |

| AHRS No. | XMC-001 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 12, 1978[1] |

| Designated NHLD | June 23, 1986[2] |

| Designated AHRS | February 2, 1972 |

Kennecott, also known as Kennicott and Kennecott Mines, is an abandoned mining camp in the Copper River Census Area in the U.S. state of Alaska that was the center of activity for several copper mines.[3] It is located beside the Kennicott Glacier, northeast of Valdez, inside Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. The camp and mines are now a National Historic Landmark District administered by the National Park Service.

It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1986.[2][4]

History

[edit]In the summer of 1900, two prospectors, "Tarantula" Jack Smith and Clarence L. Warner,[5] a group of prospectors associated with the McClellan party, spotted "a green patch far above them in an improbable location for a grass-green meadow." The green turned out to be malachite, located with chalcocite (aka "copper glance"), and the location of the Bonanza claim. A few days later, Arthur Coe Spencer, U.S. Geological Survey geologist independently found chalcocite at the same location, but was too late to stake any valuable claims.[6]: 53–55 [7]

Stephen Birch, a mining engineer just out of school, was in Alaska looking for investment opportunities in minerals. He had the financial backing of the Havemeyer Family, and another investor named James Ralph, from his days in New York. Birch spent the winter of 1901-1902 acquiring the "McClellan group's interests" for the Alaska Copper Company of Birch, Havemeyer, Ralph and Schultz, later to become the Alaska Copper and Coal Company. In the summer of 1901, he visited the property and "spent months mapping and sampling." He confirmed the Bonanza mine and surrounding by deposits were, at the time, the richest known concentration of copper in the world.[6]: 35, 55–56, 59, 73

By 1905, Birch had successfully defended the legal challenges to his property and he began the search for capital to develop the area. On June 28, 1906, he entered into "an amalgamation" with the Daniel Guggenheim and J.P. Morgan & Co., known as the Alaska Syndicate, eventually securing over $30 million. The capital was to be used for constructing a railway, a steamship line, and development of the mines. In Nov. 1906, the Alaska Syndicate bought a 40 percent interest in the Bonanza Mine from the Alaska Copper and Coal Company and a 46.2 percent interest in the railroad plans of John Rosene's Northwestern Commercial Company.[6]: 57, 71–73

Political battles over the mining and subsequent railroad were fought in the office of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt between conservationists and those having a financial interest in the copper.[6]: 88 [7]: 42

The Alaska Syndicate traded its Wrangell Mountains Mines assets for shares in the Kennecott Copper Corporation, a "new public company" formed on April 29, 1915. A similar transaction followed with the CR&NW railway and the Alaska Steamship Company. Birch was the managing partner for the Alaska operation.[6]: 75, 212–213

Kennecott Mines was named after the Kennicott Glacier in the valley below. The geologist Oscar Rohn named the glacier after Robert Kennicott during the 1899 US Army Abercrombie Survey. A "clerical error" resulted in the substitution of an "e" for the "i", supposedly by Stephen Birch himself.[6]

Kennecott had five mines: Bonanza, Jumbo, Mother Lode, Erie and Glacier. Glacier, which is really an ore extension of the Bonanza, was an open-pit mine and was only mined during the summer. Bonanza and Jumbo were on Bonanza Ridge about 3 mi (4.8 km) from Kennecott. The Mother Lode mine was located on the east side of the ridge from Kennecott. The Bonanza, Jumbo, Mother Lode and Erie mines were connected by tunnels. The Erie mine was perched on the northwest end of Bonanza Ridge overlooking Root Glacier about 3.7 mi (6.0 km) up a glacial trail from Kennecott. Ore was hoisted to Kennecott via the trams which head-ended at Bonanza and Jumbo. From Kennecott the ore was hauled mostly in 140-pound sacks on steel flat cars to Cordova, 196 rail miles away, via the Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CRNW).

In 1911 the first shipment of ore by train transpired. Before completion, the steamship Chittyna carried ore to the Abercrombie landing by Miles Glacier. Initial ore shipments contained "72 percent copper and 18 oz. of silver per ton."[6]: 135 [7]: 44, 66–67

In 1916, the peak year for production, the mines produced copper ore valued at $32.4 million.

In 1925 a Kennecott geologist predicted that the end of the high-grade ore bodies was in sight. The highest grades of ore were largely depleted by the early 1930s. The Glacier Mine closed in 1929. The Mother Lode was next, closing at the end of July 1938. The final three, Erie, Jumbo and Bonanza, closed that September. The last train left Kennecott on November 10, 1938, leaving it a ghost town.

From 1909 until 1938, except when it closed temporarily in 1932, Kennecott mines "produced over 4.6 million tons of ore that contained 1.183 billion pounds of copper mainly from three ore bodies: Bonanza, Jumbo and Mother Lode."[6]: 260 [7]: 74 The Kennecott operations reported gross revenues above $200 million and a net profit greater than $100 million.[8]

In 1938, Ernest Gruening proposed Kennecott be preserved as a National Park. A recommendation to President Franklin D. Roosevelt on January 18, 1940, for the establishment of the Kennecott National Monument went nowhere. However, December 2, 1980, saw the establishment of the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve.[6]: 261–262, 321

From 1939 until the mid-1950s, Kennecott was deserted except for a family of three who served as the watchmen until about 1952. In the late 1960s, an attempt was made to reprocess the tailings and to transport the ore in aircraft. The cost of doing so made the idea unprofitable. Around the same time, the company with land rights ordered the destruction of the town to rid them of liability for potential accidents. A few structures were destroyed, but the job was never finished and most of the town was left standing. Visitors and nearby residents have stripped many of the small items and artifacts. Some have since been returned and are held in various archives.

KCC sent a field party under the geologist Les Moon in 1955. They agreed with the 1938 conclusion, "no copper resource of a size and grade sufficient to interest KCC remained." The mill and other structures remain, however, and many are in the process of being restored.[6]: 7 [9]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 494 | — | |

| 1930 | 217 | −56.1% | |

| 1940 | 5 | −97.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] | |||

Kennecott first reported on the 1920 U.S. Census as an unincorporated village. It appeared again in 1930 and 1940, and after its abandonment, it has not reported separately since. It is now within the McCarthy CDP.

Geology

[edit]Copper ore was discovered in a lode on Chief Nikolai's house at the mouth of Dan Creek in July 1899. The geological formations in the area were described and identified by a USGS geologist by the name of Oscar Rohn in 1899. This original copper find became the basis of the Nikolai Mine in 1900. Simultaneously, placer gold was discovered on the Dan and Young Creeks. The Bonanza ore body was discovered in Aug. 1900 by Warner and Smith. Almost simultaneously, another USGS geologist named Arthur Spencer, came across the ore when mapping the area with Frank Schrader. In 1901, the Dan Creek was staked by C.L. Warner and "Dan" L. Kain. Gold was found on Chititu Creek in April 1902 by Frank Kernan and Charles Koppus.[5]: 12, 75–77 [6]: 53–55

Besides placer deposits, copper is found as polymetallic replacement deposits in the fault planes, fractures and joints of the Triassic Nikolai greenstone, which consists of basaltic lava flows, and in the base of the Upper Triassic Chitistone limestone. Minerals include chalcocite, bornite and chalcopyrite, with associated malachite, azurite and cuprite. Native copper can also be found in the greenstone.[5]: 77

-

Map of the Chitina River valley. "x" depicts a copper prospect while "+" depicts a gold placer.

-

Geologic map of the Kennecott and Bonanza Mine area. "ng" is the Nikolai greenstone formation, "Trc" is the Chitistone limestone formation, while "Qrg" are rock glaciers.

-

Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark marker for the geologic outcrop

-

Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark marker for the ore body

-

Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark marker for the mine shafts

-

Topographic map showing the location of the Erie, Jumbo, Mother Lode, Bonanza and Glacier Mines in relation to Kennecott. Note the aerial tramways and haulage tunnels.

Concentration Mill

[edit]Copper extraction was a many step process in an attempt to be as efficient as possible. Chalcocite and covellite were sent directly to the smelting plant in Tacoma. Malachite, azurite, and other forms of copper within the limestone needed separation in the 14-story mill building before shipment. The mill was mainly built between 1909 and 1923. Ore arrived at the mill via aerial tramways, where the high-grade portion (approximately 60% copper) was crushed and placed in a chute to carry it directly to the bottom to be placed in burlap sacks. Lower-grade ore was further crushed, sized and sorted. The denser ore was separated from the less dense waste via Hancock jigs and shaker tables. The tailings left over after gravity separation were further treated via ammonia leaching, for the coarse material, or via froth flotation for the fine material. The ammonia leaching plant was built in 1915, where ammonia liquefied the copper but kept the limestone in solid form. The ammonia-copper solution was heated to drive off the ammonia, which left behind a copper oxide containing 75% copper. This was then sacked for shipment. The flotation plant was built in 1923 to process the "fines", which were less than 0.3 cm in size. These fines were mixed with water, oil, and buffering chemicals, before air was bubbled through the solution. Copper ore attached to the air bubbles, and floated to the top, where it was skimmed off, dried and sacked.

-

Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark marker for the mill town

-

Kennecott-based tour groups now lead visitors on guided tours of the fourteen story concentration mill

-

Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark mine tramway ore car

Tourism

[edit]In the 1980s, Kennecott became a popular tourist destination, as people came to see the old mines and buildings. However, the town of Kennecott was never repopulated. Residents involved in the tourism industry often lived in nearby McCarthy or on private land in the surrounding area. The area was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986 and the National Park Service acquired much of the land within the Kennecott Mill Town in 1998.

Popular tourist activities while visiting Kennecott include glacier hiking, ice climbing, and touring the abandoned mill. Visitors may also hike to the abandoned Bonanza, Jumbo and Erie mines, all of which are strenuous full-day hikes, with Erie Mine being a somewhat terrifying scramble along cliffs overlooking the Stairway Icefall. Local guide services offer all of these hikes if one would like some route-finding assistance.

Accessibility

[edit]Kennecott is now accessible by air (McCarthy has a 3,500 foot (1,100 m) meter gravel runway) or by driving on the Edgerton Highway to the McCarthy Road, an unimproved gravel road. The McCarthy Road ends at the Kennicott River and a footbridge is available for pedestrian traffic to McCarthy. From McCarthy, it is 4.5 miles (7.2 km) to Kennecott, and shuttles are available.

See also

[edit]- List of National Historic Landmarks in Alaska

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Copper River Census Area, Alaska

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "Kennecott Mines". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 21, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ^ "Kennicott, Alaska". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Robert Pierce and Robert Spude. "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Kennecott Mines" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Accompanying seven photos, exterior and interior, from ca. 1925, ca. 1930, 1983 (2.50 MB) - ^ a b c Fred H. Moffit; Stephen R. Capps (1911). Geology and Mineral Resources of the Nizina District, Alaska, USGS Bulletin 448. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Charles Caldwell Hawley (2014). A Kennecott Story. The University of Utah Press. p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Elizabeth A. Tower (1990). Ghosts of Kennecott, The Story of Stephen Birch. pp. 12–14.

- ^ Alfredo O. Quinn (1995). Iron Rails to Alaskan Copper. D'Aloguin Publishing Co. p. 175.

- ^ Park, Mailing Address: Wrangell-St Elias National; Center, Preserve PO Box 439 Mile 106 8 Richardson Highway Copper; Us, AK 99573 Phone: 907 822-5234 Contact. "Kennecott Concentration Mill Building Renovations Completed - Wrangell - St Elias National Park & Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

External links

[edit]- "Kennecott Copper Mine and Glacier". Abandoned But Not Forgotten. Retrieved November 16, 2007. - images of the town and mine

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. AK-1, "Kennecott Copper Corporation"

- HAER No. AK-1-B, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, West Bunkhouse"

- HAER No. AK-1-D, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, Concentration Mill"

- HAER No. AK-1-E, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, Leaching Plant"

- HAER No. AK-1-G, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, Machine Shop"

- HAER No. AK-1-H, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, Company Store & Warehouse"

- HAER No. AK-1-J, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, Recreation Hall"

- HAER No. AK-1-M, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, Old School Building"

- HAER No. AK-1-N, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, New School Building"

- HAER No. AK-1-O, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, Firehouse"

- HAER No. AK-1-P, "Kennecott Copper Corporation, NPS Interpretation Building"

- History of Kennecott

- Tour information and photos

- National Trust for Historic Preservation article and photo essay the old Kennecott mill town

- Geography of Copper River Census Area, Alaska

- Ghost towns in Alaska

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Alaska

- Mining communities in Alaska

- Populated places on the National Register of Historic Places in Alaska

- Protected areas of Copper River Census Area, Alaska

- Tourist attractions in Copper River Census Area, Alaska

- Unused buildings in Alaska

- Ruins on the National Register of Historic Places