Kenneth Walker (general)

Kenneth Walker | |

|---|---|

Brigadier General Kenneth N. Walker | |

| Birth name | Kenneth Newton Walker |

| Nickname(s) | Ken |

| Born | 17 July 1898 Los Cerillos, New Mexico Territory |

| Died | 5 January 1943 (aged 44) Rabaul, New Britain |

| Places of Burial (markers only) |

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Aviation Section, Signal Corps United States Army Air Service United States Army Air Corps United States Army Air Forces |

| Years of service | 1917–1943 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | 0-12510 |

| Commands | |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

Brigadier General Kenneth Newton Walker (17 July 1898 – 5 January 1943) was a United States Army aviator and a United States Army Air Forces general who exerted a significant influence on the development of airpower doctrine. He posthumously received the Medal of Honor in World War II.

Walker joined the United States Army in 1917, after the American entry into World War I. He trained as an aviator and became a flying instructor. In 1920, after the end of the war, he received a commission in the Regular Army. After service in various capacities, Walker graduated from the Air Corps Tactical School in 1929, and then served as an instructor there. He supported the creation of a separate air organization that is not subordinate to other military branches. He was a forceful advocate of the efficacy of strategic bombardment, publishing articles on the subject and becoming part of a clique known as the "Bomber Mafia" that argued for the primacy of bombardment over other forms of military aviation. He advanced the notion that fighters could not prevent a bombing attack. He participated in the Air Corps Tactical School's development of the doctrine of industrial web theory, which called for precision attacks against carefully selected critical industrial targets. Shortly before the United States entered World War II, Walker became one of four officers assigned to the Air War Plans Division, which was tasked with developing a production requirements plan for the war in the air. Together, these officers devised the AWPD-1 plan, a blueprint for the imminent air war against Germany that called for the creation of an enormous air force to win the war through strategic bombardment.

In 1942, Walker was promoted to brigadier general and transferred to the Southwest Pacific, where he became Commanding General, V Bomber Command, Fifth Air Force. The Southwest Pacific contained few strategic targets, relegating the bombers to the role of interdicting supply lines and supporting the ground forces. This resulted in a doctrinal clash between Walker and Lieutenant General George C. Kenney, an attack aviator, over the proper method of employing bombers. Walker frequently flew combat missions over New Guinea, for which he received the Silver Star. On 5 January 1943, he was shot down and killed leading a daylight bombing raid over Rabaul, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Early life and World War I

[edit]Walker was born in Los Cerrillos, New Mexico, on 17 July 1898 to Wallace Walker and his wife Emma née Overturf. The family subsequently moved to Denver, Colorado. Kenneth's father left when he was young, and Emma became a single mother. Kenneth began his education at the Maria Mitchell School in Denver, Colorado, from 1905 to 1908, and then attended the Columbian School there from 1908 to 1912. He went to Central High School for a time until 1913 when he started at the Omaha High School of Commerce, from which he graduated in 1915. From January to June 1917 he took a course at the YMCA Night School in Denver. He then studied business administration at La Salle Extension University.[1]

Walker enlisted in the United States Army in Denver, on 15 December 1917. He received flight training at the University of California's School of Military Aeronautics and at the pilot training base at Mather Field, near Sacramento, California. He was awarded his Aircrew Badge and commissioned as a temporary second lieutenant in the United States Army Air Service on 2 November 1918.[2] He then attended the Flying Instructor's School at Brooks Field in San Antonio, Texas, and became an instructor at the flight training center at Barron Field. In March 1919, he was posted to Fort Sill as an instructor at the Air Service Flying School. During 1918, the School for Aerial Observers and the Air Service Flying School were built at nearby Post Field, where Walker spent the next four years as a pilot, instructor, supply officer, and post adjutant.[3]

Between the wars

[edit]Walker became one of many officers holding wartime commissions to receive a commission in the Regular Army, into which he was commissioned as a first lieutenant on 1 July 1920, but was subsequently reduced in rank to second lieutenant on 15 December 1922, another common occurrence in the aftermath of World War I when the wartime army was demobilized.[4] Already a command pilot, he also qualified as a combat observer in 1922.[3] He was promoted to first lieutenant again on 24 July 1924.[4]

Walker courted Marguerite Potter, a sorority member and sociology graduate at the Norman campus of the University of Oklahoma.[5] The two were married in September 1922. In lieu of a honeymoon, they boarded a troop transport to the Philippines on 12 December 1922. Walker initially became Commander of the Air Intelligence Section at Camp Nichols. He was then posted to the Philippine Air Depot, where he served at various times as property officer, supply officer, adjutant, and depot inspector, before ultimately being assigned to the 28th Bombardment Squadron in 1924.[6] In August 1923 he crashed an Airco DH.4 on takeoff but walked away unhurt.[7] The Walkers had two sons, Kenneth Jr., born in February 1927,[8] and Douglas, born in January 1933.[9]

Walker returned to the United States in February 1925 and was posted to Langley Field, where he became a member of the Air Service Board. He served successively as adjutant of the 59th Service Squadron, commander of the 11th Bombardment Squadron, and operations officer of the 2nd Bomb Group there. In June 1929 he graduated from the Air Corps Tactical School, where he studied under Captain Robert Olds, a former aide to air power pioneer Billy Mitchell and a passionate advocate of strategic bombing.[10] He then served at the Air Corps Tactical School as an instructor under Captain Olds in the Bombardment Section until July 1933, both at Langley and at Maxwell Field, where the school was relocated in 1931.[2] Walker became part of a small clique of Air Corps Tactical School instructors that became known as the "Bomber Mafia", that argued that bombardment was the most important form of airpower. Its members also included Haywood Hansell, Donald Wilson, Harold L. George, and Robert M. Webster,[11] Their influence was such that, during their tenure, bombardment achieved primacy over pursuit in the development of Air Corps doctrine.[12]

One of Walker's tasks was to rewrite the bombardment text. He felt it was flawed because it failed to drive home what he saw as the most important fact, that "bombardment aviation is the basic arm of the air force".[13] Following the views of air power theorists Billy Mitchell, Hugh Trenchard, and Giulio Douhet, Walker enunciated two fundamental principles: that bombardment would take the form of daylight precision bombing; and that it should be directed against critical industrial targets.[13][14] In his article "Driving Home the Bombardment Attack", published in the Coast Artillery Journal in October 1930, he argued that fighters could not prevent a bombing attack and that "the most efficacious method of stopping a bombardment attack would appear to be an offensive against the bombardment airdrome."[15] The Bomber Mafia argued that bombers flew too high and too fast to be intercepted by fighters, that even if they were intercepted, the bombers had enough firepower to drive off their attackers, and enough armor and resilience to absorb any damage their attackers might attempt to inflict.[16] The Air Corps Tactical School developed a doctrine that became known as industrial web theory, which called for precision attacks against carefully selected critical industrial targets.[17] Walker drove home his belief in bombardment with a famous dictum from his lectures: "A well-organized, well-planned, and well-flown air force attack will constitute an offensive that can not be stopped."[18]

Walker published another professional article in 1933, entitled "Bombardment Aviation: Bulwark of National Defense". "Whenever we speak in terms of 'air force' we are thinking of bombardment aviation," he wrote, dismissing other forms of aviation.[19] This was orthodox at the Air Corps Tactical School, which taught that "every dollar which goes into the building of auxiliary aviation and special types, which types are not essential for the efficient functioning of the striking force can only occur at the expense of that air force's offensive power."[20] Walker's major thesis was that "a determined air attack, once launched, is most difficult, if not impossible to stop when directed against land objectives." At the conclusion of his article, he renewed his call for the creation of an independent air force "as a force with a distinct mission, of importance co-equal to that of the Army and the Navy."[19] Walker's persistent advocacy of strategic bombing led to frequent clashes with Captain Claire Chennault, who led instruction in pursuit aviation at the Air Corps Tactical School from 1931 to 1936. Chennault believed that the right mix of fighters and ground defenses could successfully defeat a bomber assault and ridiculed Walker for suggesting that bombers could not be stopped, leading to "legendary" debates between the two.[21]

In November 1934, Walker, now a student at the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, testified with Robert Olds, Claire Chennault, Donald Wilson, Harold George and Robert Webster on the military aspects of aviation before the Howell Commission on Federal Aviation. All were current or former instructors at the Air Corps Tactical School, and all except Chennault were part of the Bomber Mafia.[11] They argued for an independent air force, in contradiction to Army doctrine. Walker told the commission: "unless we create an adequate and separate Air Force, this next war 'will begin in the air and end in the mud'-in the mud and debris of the demolished industries that have brought us to our knees."[22] They were unable to persuade the commission to recommend an independent air force, although it did agree that the Air Corps should be granted greater autonomy within the Army.[23] The commission concluded that "there is ample reason to believe that aircraft have now passed far beyond their former position as useful auxiliaries ... An adequate striking force for use against objectives both near and remote is a necessity for a modern army".[24]

The appearance in 1935 of the Boeing B-17 bomber gave the bombardment advocates the weapon they had long dreamt of. Not only could it carry an impressive bomb load of 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg) of bombs for 2,260 miles (3,640 km) or 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) for 1,700 miles (2,700 km),[25] but its top speed of 250 miles per hour (400 km/h) was faster than that of the contemporary P-26 fighter. Its high speed also led the bombardment advocates to downplay the danger posed by antiaircraft fire.[26]

Walker's marriage ended in divorce in 1934, after he had an affair. He remarried and had a son named John, but his second marriage also ended in divorce.[27] Walker graduated from the Command and General Staff School in June 1935 and was posted to Hamilton Field, first as Intelligence and Operations Officer of the 7th Bombardment Group,[2] and then as commander of the 9th Bombardment Squadron.[28] While landing a Martin B-12 bomber, he overshot the runway. The station commander, Brigadier General Henry Arnold reported that Walker, "supposed to be one of our best pilots, apparently cuts out completely, uses up 4,000 feet (1,200 m) and finally hits a concrete block and spoils a perfectly good airplane when he normally would have given her the gun and gone around again."[29] After fifteen years in the rank, jokes circulated about his being the most senior first lieutenant in the Air Corps,[4] but he was finally promoted to captain on 1 August 1935. He was temporary major from 20 October 1935 to 16 June 1936, and again on 4 October 1938, before the rank finally became substantive on 1 July 1940.[30] He had another accident in 1937, when he crashed a B-17 on takeoff from Denver Municipal Airport but this time his flying skills were credited with saving the entire crew of nine from injury.[29]

In 1938 Walker began a three-year tour in Hawaii, where he was operations officer of the 5th Bombardment Group at Luke Field, executive officer at Hickam Field, and then commander of the 18th Pursuit Group at Wheeler Field.[2] Commanding a pursuit group involved a considerable change of pace for a man whose career thus far had been spent in bombers. His adjutant, First Lieutenant Bruce K. Holloway felt that Walker never demonstrated the "emotional exhilaration toward flying a high performance machine that is so typical of fighter pilots."[31] Nor did he warm to the Curtiss P-36 Hawk fighter, especially after a near-fatal accident.[32]

World War II

[edit]Air War Plans Division

[edit]Walker returned to the United States in January 1941 and joined the Air War Plans Division in the Office of the Chief of the United States Army Air Corps in Washington, D.C., as an assistant chief of staff. Brigadier General Carl Andrew Spaatz was head of the division. Lieutenant Colonels Olds and Muir S. Fairchild, old colleagues of Walker's from the Air Corps Tactical School, were two of Spaatz' assistants.[33] Walker was promoted to temporary lieutenant colonel on 15 July 1941.[30] In the June 1941 reorganization of the Air Corps, Spaatz became chief of staff to the Commanding General, United States Army Air Forces, Major General Henry H. Arnold, who appointed Colonel Harold L. George, a former student of Walker at the Air Corps Tactical School from 1931 to 1932, to replace Spaatz as head of the Air War Plans Division. Walker joined George's planning team, along with Majors Haywood S. Hansell and Laurence S. Kuter.[34][35] All were former instructors at the Air Corps Tactical School and members of the "Bomber Mafia".[12][36]

The Air War Plans Division was tasked with developing a production requirements plan for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who wanted it by 10 September 1941.[34] In just nine days in August 1941, George, Olds, Fairchild, Walker, Kuter and Hansell drafted the AWPD-1 plan for a war against Germany.[2] Reflecting their belief in bombardment as the principal form of aviation, the plan was based upon the number of bombers that they estimated would be required to knock out Germany's key industries – electric power, transportation and petroleum. In order to neutralize anticipated opposition from the German Air Force, they planned for bombing aircraft factories and the sources of the light metals needed for aircraft production. These targets were collated along with the estimated tonnage of bombs required to destroy them.[37]

The plan called for a bomber force of 98 medium, heavy and very heavy bomber groups, totaling 6,834 aircraft. Sixteen fighter groups would defend the bombers' bases. Should this bomber force prove insufficient to defeat Germany without a major land offensive, provision was made for a tactical air force of 13 light bomber groups, two photo reconnaissance groups, five fighter groups, 108 observation squadrons and 19 transport groups. In retrospect, this part of the plan represented a considerable underestimate. The plan required 2,164,916 personnel, including 103,482 pilots. At the moment though, the United States had, as General Arnold put it, "plans but not planes". Due to poor security, verbatim extracts of AWPD-1 were published in the Chicago Tribune and other newspapers on 4 December.[37]

The war in Europe had cast grave doubt on the Air Corps' doctrine that fighters could not shoot down bombers and the bomber will always get through. In the Battle of Britain the British Royal Air Force had demonstrated that it could shoot down bombers, while its own bomber force had suffered such heavy losses over Germany that it had abandoned daylight bombing in favor of night raids. Nonetheless, the planners held firm in their belief that, since American bombers were better armed and armored than their British or German counterparts, the bombers would get through, even in daylight, and that enemy fighter strength could be destroyed on the ground by bombing airbases and factories. "Each of us," Kuter wrote years later, "scoffed at the idea that fighters would be needed to protect bombers, to enable bombers to reach their objective. In preparing AWPD-l, we stayed in that rut."[38] Walker was promoted to colonel on 1 February 1942.[2]

In April 1942 Walker joined the Operations Division (OPD) of the War Department General Staff as executive officer of Brigadier General St. Clair Streett's Theater Group. He co-authored a memorandum with Brigadier General Dwight Eisenhower in which they advanced the position that the determinations of the Joint Chiefs of Staff "must be taken as authoritative unless and until modified by the same or higher authority."[2][39] After his death, Walker was awarded the Legion of Merit in recognition of his contributions as a staff officer at OPD.[38]

Papuan Campaign

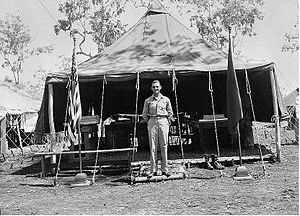

[edit]Walker was promoted to brigadier general on 17 June 1942 and was transferred to the Southwest Pacific Area,[2] flying to Australia in the company of Brigadier General Ennis Whitehead, another newly promoted brigadier general. The commander of Allied Air Forces there, Lieutenant General George Brett, aware that he would soon be replaced, sent the two newcomers on an inspection trip. Walker learned a great deal. He joined three combat missions over New Guinea, experiencing for himself the difficulties that his aircrews faced. He also experienced an air raid in Port Moresby.[40] For this, Walker was awarded the Silver Star. His citation read:

For gallantry in action over Port Moresby, New Guinea, during July 1942. This Officer took part in four different missions over enemy territory, each time being subjected to heavy enemy fire from anti-aircraft and fighter planes. The large amount of firsthand information gained by General Walker has proved of inestimable value in the performance of his duties. His complete disregard for personal safety, above and beyond the call of duty, has proved highly stimulating to the morale of all Air Force personnel with whom he has come in contact. Such courage and gallantry are in keeping with the finest American traditions and are worthy of the highest commendation.[41][42]

Brett's replacement, Major General George Kenney, arrived in the theater in August, and Walker was appointed Commanding General, V Bomber Command, Fifth Air Force on 3 September, with his headquarters in Townsville. At this time, Port Moresby was subject to frequent Japanese air raids, so the bombers were generally based in the Townsville area and staged through Port Moresby to minimize their chance of loss or damage on the ground.[43] In mid-September 1942, at the height of the Kokoda Track campaign, Kenney sent Walker to Port Moresby for a few weeks to direct the advanced echelon, to give Whitehead a rest and Walker more experience.[44] Walker attempted to lift morale by improving the men's living conditions. He made a point of small gestures of fellowship, such as standing in line with the men at meal times. But what endeared him most to his men was his willingness to share the dangers as well as their hardships, by flying a mission a week on average.[45] In October, General Douglas MacArthur gave Kenney a dressing down for flying over the Owen Stanley Range. In turn, Kenney ordered Walker, Wilson and Whitehead not to fly any more missions. For a variety of reasons, all four of them eventually disobeyed their orders.[46]

The Southwest Pacific was not a promising theater of war for the strategic bomber. The bombers of the day did not have the range to reach Japan from Australia,[47] and there were no typical strategic targets in the theater other than a few oil refineries. Thus, "The air mission was to interdict Japan's sea supply lanes and enable the ground forces to conduct an island-hopping strategy."[48] This set up a doctrinal clash between Kenney, an attack aviator, and Walker, the bomber advocate. The long-standing Air Corps tactic for attacking shipping called for large formations of high-altitude bombers. With sufficient mass, so the theory went, bombers could bracket any ship with walls of bombs, and do so from above the effective range of the ship's anti-aircraft fire. However the theoretical mass required was two orders of magnitude greater than what was available in the Southwest Pacific.[49] A dozen or so bombers was the most that could be put together, owing to the small number of aircraft in the theater and the difficulties of keeping them serviceable. The results were therefore generally ineffective, and operations incurred heavy casualties.[50]

Walker objected to Kenney's suggestion that the bombers conduct attacks from low level with bombs armed with instantaneous fuses.[44] Kenney ordered Walker to try the instantaneous fuses for a couple of months, so that data could be gained about their effectiveness;[51] a few weeks later Kenney discovered that Walker had discontinued the use of the instantaneous fuses. In November, Kenney arranged for a demonstration attack on the SS Pruth, a ship that had sunk off Port Moresby in 1924 and was often used for target practice.[52] After the attack Walker and Kenney took a boat out to the wreck to inspect the damage. As expected, none of the four bombs dropped had hit the stationary wreck; but the instantaneous fuses had detonated the bombs when they struck the water, and bomb fragments had torn holes in the sides of the ship. Walker reluctantly conceded the point.[53] "Ken was okay," Kenney later recalled. "He was stubborn, over-sensitive, and a prima donna, but he worked like a dog all the time. His gang liked him a lot but he tended to get a staff of 'yes-men'. He did not like to delegate authority. I was afraid that Ken was not durable enough to last very long under the high tension of this show."[54]

In December, Kenney learned that Whitehead had been on board a B-25 in which a Japanese antiaircraft gun had blown a hole in the wing "big enough for him to jump through without touching the sides",[55] and that Walker had flown on a B-17 that had clipped a tree and lost part of a wing.[56] Kenney then repeated his earlier order, explaining the reasons behind it:

I told him that from then on I wanted him to run his command from his headquarters. In the airplane he was just extra baggage. He was probably not as good in any job on the plane as the man already assigned to it. In fact, in case of trouble, he was in the way. On the other hand, he was the best bombardment commander I had and I wanted to keep him so that the planning and direction would be good and his outfit take minimum losses in the performance of their missions. One of the big reasons for keeping him home was that I would hate to have him taken prisoner by the Japs. They would have known that a general was bound to have access to a lot of information and there was no limit to the lengths they would go to extract that knowledge from him. We had plenty of evidence that the Nips had tortured their prisoners until they either died or talked. After the prisoners talked they were beheaded, anyhow, but most of them had broken under the strain. I told Walker that frankly I didn't believe he could take it without telling everything he knew, so I was not going to let him go on any more combat missions.[55]

On 9 January 1943, MacArthur issued a communiqué praising the forces under his command for the victory that had been achieved at Buna and announcing the award of the Distinguished Service Cross to twelve officers, including Walker.[57]

Rabaul 5 January 1943

[edit]On 3 January 1943, Kenney received intelligence from Allied Ultra codebreakers that the Japanese were about to attempt a reinforcement run from their main base at Rabaul to Lae, on the mainland of New Guinea.[58] He ordered Walker to carry out a full-scale dawn attack on the harbor's shipping before it could depart. Walker demurred. His bombers would have difficulty making their rendezvous if they had to leave Port Moresby in the dark. He recommended a noon attack instead. Kenney acknowledged Walker's concerns but was insistent; he preferred bombers out of formation to bombers shot down by the enemy fighters that were certain to intercept a daylight attack.[59] In spite of this, Walker ordered that the attack be made at noon on 5 January.[60]

Bad weather over northern Australia prevented participation by the bombers there, which left Walker with only those based at Port Moresby: six B-17s and six B-24s. This force was far too small for the tactics that he wanted to use.[61] He flew in the lead plane, B-17 #41-24458, nicknamed "San Antonio Rose I", from the 64th Bombardment Squadron, 43rd Bombardment Group, which was piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Jack W. Bleasdale, the group's executive officer. The 64th Bombardment Squadron's commanding officer, Major Allen Lindberg was also on board. The briefing officer for the mission, Major David Hassemer, did not think that it was a good idea for so many senior officers to fly in the same plane, but his objection was overruled.[62]

They encountered heavy flak and continuous fighter attacks. Owing to the delay, the ten-ship convoy that they were sent to attack had departed two hours earlier, but there were still plenty of targets.[61] Forty 500-pound (230 kg) and twenty four 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs were dropped from 8,500 feet (2,600 m). The mission claimed hits on nine ships, totaling 50,000 tons.[63] After the war, JANAC confirmed the sinking of only one Japanese merchant ship, the 5,833-ton Keifuku Maru.[64] Two other ships were damaged, as was the destroyer Tachikaze.[65] Two B-17s were shot down, including Walker's.[63]

Fred Wesche flew the 5 January mission over Rabaul. He later recalled:

On January 5th of 1943, I was on one of what most of us thought was a suicide mission ... The Japanese were getting ready to mount a large expeditionary force to relieve their garrisons on New Guinea, and Brigadier General Walker, who was the commanding general of the V Bomber Command there, was flying in the lead ship, and I was flying on his wing. When it was announced that it was going to be done in broad daylight at noontime, as a matter-of-fact, at low altitude, something like 5000 feet over the most heavily defended target in the Pacific almost ... most of us went away shaking our heads. Many of us believed we wouldn't come back from it. Anyway, we went over the target and all of us got attacked. I was shot up. Nobody was injured, fortunately, but the airplane was kind of banged up a little bit. We had to break formation over the target to bomb individually and then we were supposed to form up immediately after crossing the target, but no sooner had we dropped our bombs that my tail gunner says, "Hey, there's somebody in trouble behind us" So we made a turn and looked back and here was an airplane, one of our airplanes, going down, smoking and on fire, not necessarily fire, but smoke anyway, and headed down obviously for a cloud bank with a whole cloud of fighters on top of him. There must have been 15 or 20 fighters. Of course they gang up on a cripple, you know, polish that one off with no trouble, but he disappeared into a cloud bank and we never saw him again. It turns out it was the general ... He actually had a pilot, but he was the overall air commander for the operation. He was conducting it from the astrodome, just behind the pilot's seat, where he could look out with a microphone and directing what should be done and so on ... The results of the raid, I'm not sure what it was, whether it was successful or not, but it certainly was a most hair-raising experience you want to go through. I mean, suddenly, you look ahead of you and see about fifteen or twenty airplanes all shooting at you at the same time, you see ... he won the Congressional Medal for that. The rest of us got the Air Medal, and, of course, he did all the planning and whatnot, too, even though many of us thought it was foolhardy, to tell you the truth.[66]

Kenney was furious when he discovered that Walker had not only changed the takeoff time without notice, but had also defied his orders by accompanying the mission. He told MacArthur that when Walker showed up he was going to give him a reprimand and send him back to Australia on leave for two weeks. "Alright George," MacArthur replied, "but if he doesn't come back, I'm going to send his name in to Washington recommending him for a Congressional Medal of Honor."[67] All available aircraft were sent to search for Walker, preventing attacks on the Japanese convoy as it headed for Lae. They managed to locate and rescue the crew of the other B-17 that had been shot down in the raid, but not Walker's.[68]

MacArthur's recommendation therefore went ahead. His previous award of the Distinguished Service Cross was cancelled and upgraded to the Medal of Honor on 11 March.[69][70] The Adjutant General, Major General James A. Ulio, queried whether it was "considered above and beyond the call of duty for the commanding officer of a bomber command to accompany it on bombing missions against enemy held territory." Major General George Stratemeyer, the chief of the air staff, replied that it was.[71] In March 1943, Roosevelt presented Kenneth Walker Jr. with the medal in a ceremony at the White House. It was one of 38 Medals of Honor awarded to flying personnel of the US Army Air Forces in World War II.[72] The citation read:

For conspicuous leadership above and beyond the call of duty involving personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to life. As commander of the V Bomber Command during the period from 5 September 1942, to 5 January 1943, Brigadier General Walker repeatedly accompanied his units on bombing missions deep into enemy-held territory. From the lessons personally gained under combat conditions, he developed a highly efficient technique for bombing when opposed by enemy fighter airplanes and by antiaircraft fire. On 5 January 1943, in the face of extremely heavy antiaircraft fire and determined opposition by enemy fighters, he led an effective daylight bombing attack against the shipping in the harbor at Rabaul, New Britain, which resulted in direct hits on 9 enemy vessels. During this action his airplane was disabled and forced down by the attack of an overwhelming number of enemy fighters.[73]

Neither Walker's body nor the wreck of his aircraft was found.[74] Walker was therefore listed on the Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery and Memorial, Philippines, where servicemen missing in action or buried at sea in the Southwest Pacific are commemorated. On 7 December 2001, a headstone marker was erected in Section MC-36M of Arlington National Cemetery to give family members a place to gather in the United States.[75]

Awards and decorations

[edit]General Walker's military awards include:

| ||||

Source: Fogerty, USAF Historical Study 91, Biographical Data on Air Force General Officers 1917–1952 (1953) Air Force Historical Research Agency

Legacy

[edit]In January 1948, Roswell Army Air Field in Roswell, New Mexico, was renamed Walker Air Force Base in honor of Walker.[76] The base was inactivated on 2 July 1965 and closed on 30 June 1967.[77] Walker Hall, and its Walker Air Power Room, at Maxwell Air Force Base, home of the Air Force Doctrine Development and Education Center, are also named after him.[76] The Walker Papers is an Air Force Fellows program that annually honors the top three research papers produced by Air Force Fellows with the Walker Series award. The Walker Series recognizes the contributions each Fellow has made to research supporting air and space power and its use in the implementation of US strategic policy.[78]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Byrd 1997, pp. 1–3

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Biographies: Brigadier General Kenneth Newton Walker". United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 13 June 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ^ a b Byrd 1997, pp. 5–6

- ^ a b c Byrd 1997, p. 45

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 8

- ^ Byrd 1997, pp. 10–12

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 14

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 31

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 50

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 26

- ^ a b Boyne 2003, p. 81

- ^ a b c Boyne 2003, pp. 82–83

- ^ a b Johnson 1998, p. 156

- ^ Hansell 1972, p. 4

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 27

- ^ Severs 1997, p. 4

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 34

- ^ Meilinger 1998, p. 850; See also Biddle 2004, p. 142

- ^ a b Walker 1933, pp. 15–19

- ^ Tonnell 2002, p. 30

- ^ Biddle 2004, p. 169

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 149

- ^ Johnson 1998, pp. 159–161

- ^ Tate 1998, pp. 149–150

- ^ Tonnell 2002, pp. 28–29

- ^ Johnson 1998, p. 162

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 51

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 52

- ^ a b Byrd 1997, p. 54

- ^ a b Fogerty 1953

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 57

- ^ Byrd 1997, pp. 56–58

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 64

- ^ a b Byrd 1997, p. 66

- ^ Clodfelter 1994, p. 88

- ^ Tonnell 2002, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b Cate & Williams 1948, pp. 148–150

- ^ a b Byrd 1997, p. 75

- ^ Cline 1951, p. 170

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 90

- ^ "Wings of Valor II – Kenneth Walker, Court Martial or Medal". HomeOfHeroes.com. Archived from the original on 2009-03-13. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Kenneth Walker". Hall of Valor. Military Times. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ Watson 1950, pp. 98–99

- ^ a b Byrd 1997, p. 97

- ^ Gamble 2010, p. 242

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 115

- ^ Rodman 2005, p. 14

- ^ Rodman 2005, p. 24

- ^ Rodman 2005, pp. 28–29

- ^ Kenney 1949, pp. 42–45

- ^ Gamble 2010, p. 241

- ^ Gamble 2010, pp. 272–273

- ^ Kenney 1949, p. 142

- ^ Kenney 1949, p. 143

- ^ a b Kenney 1949, p. 167

- ^ Gamble 2010, p. 273

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 121

- ^ Kreis 1996, p. 265

- ^ Kenney 1949, pp. 175–176

- ^ Gamble 2010, p. 278

- ^ a b Gamble 2010, p. 280

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 118

- ^ a b Watson 1950, pp. 138–139

- ^ Watson 1950, p. 716

- ^ Gamble 2010, p. 283

- ^ "Oral History Archives of World War II: Interview with Frederick Wesche III, Rutgers College Class of 1939". Rutgers University. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Kenney 1949, pp. 176

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 120

- ^ "Air Force Award Cards: Distinguished Service Cross (Canceled)". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 11 March 1943. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "Air Force Award Cards: Medal of Honor". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 11 March 1943. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ Byrd 1997, p. 126

- ^ Kenney 1949, p. 216

- ^ "Medal of Honor recipients World War II (T–Z)". United States Army. Archived from the original on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ "B-17F-10-BO "San Antonio Rose" Serial Number 41-24458". Pacific Wrecks.org. 4 February 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ "Kenneth Newton Walker at Arlington National Cemetery". Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ a b Byrd 1997, p. 135

- ^ "History of Walker Air Force Base". Walker Aviation Museum. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ "Air Force Fellows". United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

References

[edit]- Biddle, Tami Davis (2004). Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Ideas About Strategic Bombing, 1914–1945. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12010-2.

- Boyne, Walter (September 2003). "The Tactical School". Air Force Magazine. Vol. 86, no. 9. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- Byrd, Martha (1997). Kenneth N. Walker: Airpower's Untempered Crusader (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. OCLC 39709748. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- Cline, Ray S. (1951). Washington Command Post: The Operations Division. United States Army in World War II. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-001900-5. OCLC 53302987. CMH pub 1-2.

- Clodfelter, Mark (January 1994). "Pinpointing Devastation: American Air Campaign Planning Before Pearl Harbor". The Journal of Military History. 58 (1): 75–101. doi:10.2307/2944180. JSTOR 2944180. S2CID 163756756.

- Cate, James Lea; Williams, E. Kathleen (1948). "The Air Corps Prepares for War 1939–41". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea (eds.). Vol. I, Plans and Early Operations, January 1939 to August 1942. The Army Air Forces in World War II. University of Chicago Press. pp. 151–193. OCLC 222565036. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Fogerty, Dr Robert O. (1953). USAF Historical Study 91, Biographical Data on Air Force General Officers 1917–1952 (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- Gamble, Bruce (2010). Fortress Rabaul: The Battle for the Southwest Pacific, January 1941 – April 1943. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2350-2. OCLC 437298983.

- Hansell, Haywood (1972). The Air Plan That Defeated Hitler. Atlanta, Georgia: Arno Press. OCLC 579354.

- Johnson, David E. (1998). Fast Tanks and Heavy Bombers: Innovation in the U.S. Army, 1917–1945. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8847-4. OCLC 38602804.

- Kenney, George C. (1949). General Kenney Reports: A Personal History of the Pacific War (PDF). New York, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. ISBN 978-0-912799-44-5. OCLC 1227801. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- Kreis, John F., ed. (1996). Piercing the Fog: Intelligence and Army Air Forces Operations in World War II. Bolling Air Force Base, District of Columbia: Air Force History and Museums Program. ISBN 978-1-4102-1438-6. OCLC 32396801.

- Meilinger, Phillip (October 1998). "U.S. Air Force Leaders: A Biographical Tour". The Journal of Military History. 62 (4): 833–870. doi:10.2307/120180. JSTOR 120180.

- Rodman, Matthew K. (2005). A War of Their Own: Bombers over the Southwest Pacific (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. ISBN 978-1-58566-135-0. OCLC 475083118. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Severs, Hugh G. (1997). The Controversy Behind the Air Corps Tactical School's Strategic Bombardment Theory: An Analysis of the Bombardment Versus Pursuit Aviation Data between 1930–1939 (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. OCLC 227967331. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- Tate, James P. (1998). The Army and its Air Corps: Army Policy toward Aviation 1919–1941. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. ISBN 978-0-16-061379-1. OCLC 39380518. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- Tonnell, Brian W. (2002). Will the Bombers Always Get Through? The Air Force and its Reliance on Technology. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. OCLC 74261555. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- Walker, Kenneth N. (August 1933). "Bombardment Aviation: Bulwark of National Defense". U.S. Air Services. XVIII (8): 15–19.

- Watson, Richard L. (1950). "The Battle of the Bismarck Sea". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea (eds.). Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944. The Army Air Forces in World War II. University of Chicago Press. pp. 129–162. OCLC 30194835. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- 1898 births

- 1943 deaths

- Aerial disappearances of military personnel in action

- American aviators

- Aviators from New Mexico

- Aviators killed by being shot down

- Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents

- Military personnel from New Mexico

- Missing in action of World War II

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- Technical High School (Omaha, Nebraska) alumni

- United States Army Air Forces generals

- United States Army Air Forces generals of World War II

- United States Army Air Forces personnel killed in World War II

- United States Army Air Forces Medal of Honor recipients

- United States Army Air Service pilots of World War I

- Air Corps Tactical School alumni

- Air Corps Tactical School faculty

- United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- United States Army officers

- World War II recipients of the Medal of Honor

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1943

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in Papua New Guinea