Kenny Dalglish

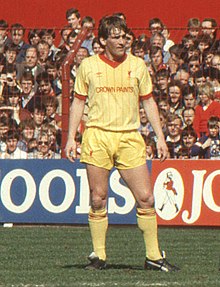

Dalglish in 2009 | |||

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Kenneth Mathieson Dalglish[1] | ||

| Date of birth | 4 March 1951[1] | ||

| Place of birth | Glasgow, Scotland | ||

| Height | 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m)[2] | ||

| Position(s) | Forward | ||

| Youth career | |||

| 1967–1968 | Cumbernauld United | ||

| 1968–1969 | Celtic | ||

| Senior career* | |||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) |

| 1969–1977 | Celtic | 204 | (111) |

| 1977–1990 | Liverpool | 355 | (118) |

| Total | 559 | (229) | |

| International career | |||

| 1972–1976 | Scotland U23[3] | 4 | (2) |

| 1971–1986 | Scotland | 102 | (30) |

| Managerial career | |||

| 1985–1991 | Liverpool | ||

| 1991–1995 | Blackburn Rovers | ||

| 1997–1998 | Newcastle United | ||

| 2000 | Celtic (interim) | ||

| 2011–2012 | Liverpool | ||

| *Club domestic league appearances and goals | |||

Sir Kenneth Mathieson Dalglish MBE (born 4 March 1951) is a Scottish former football player and manager. He is regarded as one of the greatest players of all time as well as one of Celtic's, Liverpool's and Britain's greatest ever players.[4] During his career, he made 338 appearances for Celtic and 515 for Liverpool, playing as a forward, and earned a record 102 caps for the Scotland national team, scoring 30 goals, also a joint record. Dalglish won the Ballon d'Or Silver Award in 1983, the PFA Players' Player of the Year in 1983, and the FWA Footballer of the Year in 1979 and 1983. In 2009, FourFourTwo magazine named Dalglish the greatest striker in post-war British football, and he has been inducted into both the Scottish and English Football Halls of Fame. He is very highly regarded by Liverpool fans, who still affectionately refer to him as King Kenny, and in 2006 voted him top of the fans' poll "100 Players Who Shook the Kop".

Sir Kenneth began his career with Celtic in 1971, going on to win four Scottish league championships, four Scottish Cups and one Scottish League Cup with the club. In 1977, Liverpool manager Bob Paisley paid a British transfer record of £440,000 to take Dalglish to Liverpool. His years at Liverpool were among the club's most successful periods, as he won six English league championships, the FA Cup, four League Cups, five FA Charity Shields, three European Cups and one European Super Cup. In international football, Dalglish made 102 appearances and scored 30 goals for Scotland between 1971 and 1986, becoming their most capped player and joint-leading goal scorer (with Denis Law). He was chosen for Scotland's FIFA World Cup squads in 1974, 1978, 1982 and 1986, playing in all of those tournaments except the latter, due to injury.

Dalglish became player-manager of Liverpool in 1985 after the resignation of Joe Fagan, winning a further three First Divisions, two FA Cups and four FA Charity Shields, before resigning in 1991. Eight months later, Dalglish made a return to football management with Blackburn Rovers, whom he led from the Second Division to win the Premier League in 1995. Soon afterwards, he stepped down as manager to become Director of Football at the club, before leaving altogether in 1996. In January 1997, Dalglish took over as manager at Newcastle United. Newcastle finished as runners-up in the Premier League during his first season, but they only finished 13th in 1997–98, which led to his dismissal the following season. Dalglish went on to be appointed Director of Football at Celtic in 1999, and later briefly manager. He won the Scottish League Cup in 2000 before an acrimonious departure that year.

Between 2000 and 2010, Dalglish focused on charitable concerns, founding The Marina Dalglish Appeal with his wife to raise money for cancer care. In January 2011, Dalglish returned to Liverpool for a spell as caretaker manager after the dismissal of Roy Hodgson, becoming the permanent manager in May 2011. Despite winning the League Cup, which was the club's first trophy since 2006, earning them a place in the UEFA Europa League, and reaching the FA Cup Final, Liverpool only finished 8th in the Premier League, and Dalglish was dismissed in May 2012. In October 2013, Dalglish returned to Anfield as a non-executive director, and Anfield's Centenary Stand was renamed after him in October 2017.

Early life

[edit]The son of an engineer, Dalglish was born in Dalmarnock in the east end of Glasgow and was brought up in Milton in the north of the city. When he was 14 the family moved to a newly built tower block in Ibrox overlooking the home ground of Rangers, the club he had grown up supporting.[5][6][7]

Dalglish attended Miltonbank Primary School in Milton and started out as a goalkeeper.[8] He then attended High Possil Senior Secondary School,[7] where he won the inter-schools five-a-side and the inter-year five-a-side competitions. He won the Scottish Cup playing for Glasgow Schoolboys and Glasgow Schools, and was then selected for the Scottish schoolboys team that went undefeated in a Home Nations Victory Shield tournament.[8] In 1966, Dalglish had unsuccessful trials at West Ham United and Liverpool.[9]

Club career

[edit]Celtic

[edit]Dalglish signed a professional contract with Celtic in May 1967. The club's assistant manager Sean Fallon went to see Dalglish and his parents at their home, which had Rangers-related pictures on the walls.[7] In his first season, Dalglish was loaned out to Cumbernauld United, for whom he scored 37 goals.[10] During this time he also worked as an apprentice joiner.[7][8] Celtic manager Jock Stein wanted Dalglish to spend a second season at Cumbernauld, but the youngster wanted to turn professional.[11] Dalglish got his wish and became a regular in the reserve team known as the Quality Street Gang, due to it containing a large number of highly rated players, including future Scottish internationals Danny McGrain, George Connelly, Lou Macari and David Hay.[12] Dalglish made his first-team competitive debut for Celtic in a Scottish League Cup quarter-final tie against Hamilton Academical on 25 September 1968, coming on as a second-half substitute in a 4–2 win.[11][13]

He spent the 1968–69 season playing for the reserves, though scored just four goals in 17 games. The following season he changed his position, moving into midfield, and enjoyed a good season as he helped the reserve team to the league and cup double, scoring 19 goals in 31 games.[11] Stein put Dalglish in the starting XI for the first team in a league match against Raith Rovers on 4 October 1969. Celtic won 7–1 but Dalglish didn't score, nor did he score in the next three first-team games he played in during the 1969–70 season.[11][14]

Dalglish continued his goal-scoring form in the reserves into the next season, scoring 23 goals.[11] A highlight of his season came in the Reserve Cup Final against Rangers; Dalglish scored one goal in a 4–1 win in the first leg, then in the second leg scored a hat-trick in a 6–1 win to clinch the cup.[11] Still not a first-team regular, Dalglish was in the stands when the Ibrox disaster occurred at an Old Firm match in January 1971, when 66 Rangers fans died.[15] On 17 May 1971, he played for Celtic against Kilmarnock in a testimonial match for the Rugby Park club's long serving midfielder Frank Beattie, and scored six goals in a 7–2 win for Celtic.[16]

The 1971–72 season saw Dalglish finally establish himself in the Celtic first team,.[11] He scored his first competitive goal for the first team on 14 August 1971, Celtic's second goal with a penalty kick in a 2–0 win over Rangers at Ibrox Stadium.[17] He went on to score 29 goals in 53 games that season, including a hat-trick against Dundee and braces against Kilmarnock and Motherwell[18] and helped Celtic win their seventh consecutive league title.[11] Dalglish also played in Celtic's 6–1 win over Hibernian in the 1972 Scottish Cup Final.[11] In 1972–73 Dalglish was Celtic's leading scorer, with 39 goals in all competitions,[18] and the club won the league championship once again.[11] Celtic won a league and cup double in 1973–74[11] and reached the semi-finals of the European Cup. The ties against Atlético Madrid were acrimonious, and Dalglish described the first leg in Glasgow where the Spanish side had three players sent off as "without doubt the worst game I have ever played in as far as violence is concerned."[11] Dalglish won a further Scottish Cup winner's medal in 1975, providing the cross for Paul Wilson's opening goal in a 3–1 win over Airdrieonians in what transpired to be captain Billy McNeill's last match before retiring from playing football.[19]

Dalglish was made Celtic captain in the 1975–76 season, during which the club failed to win a trophy for the first time in 12 years.[20] Jock Stein had been badly injured in a car crash and missed most of that season while recovering from his injuries.[21] Celtic won another league and cup double in 1976–77, with Dalglish scoring 27 goals in all competitions.[11] On 10 August 1977, after making 320 appearances and scoring 167 goals for Celtic, Dalglish was signed by Liverpool manager Bob Paisley for a British transfer fee record of £440,000 (£3,453,000 today).[22] The deal was unpopular with the Celtic fans, and Dalglish was booed by the crowd when he returned to Celtic Park in August 1978 to play in a testimonial match for Stein.[23]

Liverpool

[edit]

Dalglish was signed to replace Kevin Keegan and quickly settled into his new club. He made his debut on 13 August 1977 in the season opener at Wembley, in the 1977 FA Charity Shield against Manchester United.[24] He scored his first goal for Liverpool in his league debut a week later on 20 August, against Middlesbrough.[24] Dalglish also scored three days later on his Anfield debut in a 2–0 victory over Newcastle United, and he scored Liverpool's sixth goal when they beat Keegan's Hamburg 6–0 in the second leg of the 1977 European Super Cup.[25][26] By the end of his first season with Liverpool, Dalglish had played 62 times and scored 31 goals, including the winning goal in the 1978 European Cup Final at Wembley against Bruges.[27]

In his second season, Dalglish recorded a personal best of 21 league goals for the club and was also named Football Writers' Association Footballer of the Year.[28][29] He did not miss a league game for Liverpool until the 1980–81 season, when he appeared in 34 out of 42 league games and scored only eight goals as Liverpool finished fifth in the league, but still won the European Cup and Football League Cup.[30] He recovered his goal-scoring form the following season, and was an ever-present player in the league once again, scoring 13 goals as Liverpool became league champions for the 13th time, and the third time since Dalglish's arrival. It was also around this time that he began to form a potent strike partnership with Ian Rush;[31] Dalglish began to play just off Rush, "running riot in the extra space afforded to him in the hole".[32] Dalglish was voted PFA Players' Player of the Year for the 1982–83 season,[33] during which he scored 18 league goals as Liverpool retained their title. From 1983 Dalglish became less prolific as a goal-scorer, though he remained a regular player.[34]

After becoming player-manager on the retirement of Joe Fagan in the 1985 close season and in the aftermath of the Heysel Stadium disaster, Dalglish selected himself for just 21 First Division games in 1985–86 as Liverpool won the double, but he started the FA Cup final win over Everton.[35][36][37] On the last day of the league season, his goal in a 1–0 away win over Chelsea gave Liverpool their 16th league title.[38] Dalglish had a personally better campaign in the 1986–87 season, scoring six goals in 18 league appearances, but by then he was committed to giving younger players priority for a first-team place.

With the sale of Ian Rush to Juventus in 1987, Dalglish formed a new striker partnership of new signings John Aldridge and Peter Beardsley for the 1987–88 season, and he played only twice in a league campaign which saw Liverpool gain their 17th title. Dalglish did not play in Liverpool's 1988–89 campaign, and he made his final league appearance on 5 May 1990 as a substitute against Derby. At 39, he was one of the oldest players ever to play for Liverpool.[39] His final goal had come three years earlier, in a 3–0 home league win over Nottingham Forest on 18 April 1987.[40]

International career

[edit]Tommy Docherty gave Dalglish his debut for the Scottish national side as a substitute in the 1–0 Euro 1972 qualifier victory over Belgium on 10 November 1971 at Pittodrie.[41] Dalglish scored his first goal for Scotland a year later on 15 November 1972 in the 2–0 World Cup qualifier win over Denmark at Hampden Park.[41] Scotland would go on to qualify for the final tournament and he was part of Scotland's 1974 World Cup squad in West Germany. He started in all three games as Scotland were eliminated during the group stages despite not losing any of their three games.[42]

In 1976, Dalglish scored the winning goal for Scotland at Hampden Park against England, by nutmegging Ray Clemence.[43] A year later Dalglish scored against the same opponents and goalkeeper at Wembley, in another 2–1 win.[44] Dalglish went on to play in both the 1978 World Cup in Argentina where he started in all of Scotland's games – scoring against eventual runners-up the Netherlands in a famous 3–2 win[45] – and the 1982 World Cup in Spain, scoring against New Zealand.[46] On both occasions Scotland failed to get past the group stage. Dalglish was selected for the 22-man squad travelling to Mexico for the 1986 World Cup, but had to withdraw due to injury.[47]

In total, Dalglish played 102 times for Scotland (a national record) and he scored 30 goals (also a national record, which matched that set by Denis Law).[48][49] He became the first, and as of 2024 only, player to win 100 caps for Scotland in a friendly match against Romania on 26 March 1986 at Hampden Park. He was presented with the milestone cap by Franz Beckenbauer prior to kick off.[50] His final appearance for Scotland, after 15 years as a full international, was on 12 November 1986 at Hampden in a Euro 1988 qualifying game against Luxembourg, which Scotland won 3–0.[51] His 30th and final international goal had been two years earlier, on 14 November 1984, in a 3–1 win over Spain in a World Cup qualifier, also at Hampden Park.[52]

Managerial career

[edit]Liverpool

[edit]After the Heysel Stadium disaster in 1985 and Joe Fagan's subsequent resignation as manager, Dalglish became player-manager of Liverpool. In his first season in charge in 1985–86, he guided the club to its first "double". Liverpool achieved this by winning the League Championship by two points over Everton (Dalglish himself scored the winner in a 1–0 victory over Chelsea at Stamford Bridge to secure the title on the final day of the season),[38] and the FA Cup by beating Everton in the final.[53]

The 1986–87 season was trophyless for Liverpool. They lost 2–1 to Arsenal in the League Cup final at Wembley. Before the 1987–88 season, Dalglish signed two new players: striker Peter Beardsley from Newcastle and winger John Barnes from Watford. He had already purchased goalscorer John Aldridge from Oxford United (a replacement for Ian Rush, who was moving to Italy) in the spring of 1987 and early into the new campaign, bought Oxford United midfielder Ray Houghton. The new-look Liverpool side shaped by Dalglish topped the league for almost the entire season, and had a run of 37 matches unbeaten in all competitions (including 29 in the league; 22 wins and 7 draws) from the beginning of the season to 21 February 1988, when they lost to Everton in the league. Liverpool were crowned champions with four games left to play, having suffered just two defeats from 40 games. However, Dalglish's side lost the 1988 FA Cup Final to underdogs Wimbledon.[54]

In the summer of 1988, Dalglish re-signed Ian Rush. Liverpool beat Everton 3–2 after extra time in the second all-Merseyside FA Cup final in 1989, but was deprived of a second Double in the final game of the season, when Arsenal secured a last-minute goal to take the title from Liverpool. In the 1989–90 season Liverpool won their third league title under Dalglish. They missed out on the Double and a third successive FA Cup final appearance when they lost 4–3 in extra-time to Crystal Palace in an FA Cup semi-final at Villa Park.[55] At the end of the season Dalglish received his third Manager of the Year award. Dalglish resigned as manager of Liverpool on 22 February 1991, two days after a 4–4 draw with rivals Everton in an FA Cup fifth round tie at Goodison Park,[56] in which Liverpool surrendered the lead four times. At the time of his resignation, the club were three points ahead in the league and still in contention for the FA Cup.[57][58]

Hillsborough disaster

[edit]Dalglish was the manager of Liverpool at the time of the Hillsborough disaster on 15 April 1989. The disaster claimed 94 lives on the day, with the final death toll reaching 97. Dalglish attended all the funerals of the victims, including four in one day.[59][60][61] His presence in the aftermath of the disaster has been described as "colossal and heroic".[62] Dalglish broke a twenty-year silence about the disaster in March 2009, expressing regret that the police and the FA did not consider delaying the kick-off of the match.[63] During the Hillsborough Memorial Service on 15 April 2011, Liverpool MP Steve Rotheram announced he would submit an early day motion to have Dalglish knighted, "not only for his outstanding playing and managerial career, but also the charity work he has done with his wife, Marina, for breast cancer support and what he did after Hillsborough. It is common knowledge it affected him deeply".[64]

Blackburn Rovers

[edit]Dalglish returned to management in October 1991 at Second Division Blackburn Rovers who had recently been purchased by multi-millionaire Jack Walker.[65][66] By the turn of 1992 they were top of the Second Division, and then suffered a dip in form before recovering to qualify for the playoffs,[67] during which Dalglish led Blackburn into the new Premier League by beating Leicester City 1–0 in the Second Division play-off final at Wembley.[68] The resulting promotion meant that Blackburn were back in the top flight of English football for the first time since 1966.[69] In the 1992 pre-season, Dalglish signed Southampton's Alan Shearer for a British record fee of £3.5 million.[70] Despite a serious injury which ruled Shearer out for half the season, Dalglish achieved fourth position with the team in the first year of the new Premier League. The following year, Dalglish failed in an attempt to sign Roy Keane.[71] Blackburn finished two positions higher the following season, as runners-up to Manchester United. By this time, Dalglish had added England internationals Tim Flowers and David Batty to his squad.[72][73]

At the start of the 1994–95 season Dalglish paid a record £5 million for Chris Sutton, with whom Shearer formed an effective strike partnership.[74] By the last game of the season, both Blackburn and Manchester United were in contention for the title. Blackburn had to travel to Liverpool, and Manchester United faced West Ham United in London. Blackburn lost 2–1, but still won the title since United failed to win in London.[75] The title meant that Dalglish was only the fourth football manager in history to lead two different clubs to top-flight league championships in England, after Tom Watson, Herbert Chapman and Brian Clough. Dalglish became Director of Football at Blackburn in June 1995.[76] He left the club at the start of the 1996–97 season after a disappointing campaign under his replacement and former assistant manager, Ray Harford.[77]

Following his departure from Blackburn Dalglish was appointed for a brief spell as an "international talent scout" at his boyhood club Rangers.[78][79] He was reported as having played a central role in the signing of Chile international Sebastián Rozental.[80]

Newcastle United

[edit]In January 1997, Dalglish was appointed manager of Premier League side Newcastle United on a three-and-a-half-year contract, taking over from Kevin Keegan.[81] Dalglish guided the club from fourth position to a runner-up spot in May and a place in the new format of the following season's UEFA Champions League.[82] He then broke up the team which had finished second two years running, selling popular players like Peter Beardsley, Lee Clark, Les Ferdinand and David Ginola and replacing them with ageing stars like John Barnes (34), Ian Rush (36) and Stuart Pearce (35), as well as virtual unknowns like Des Hamilton and Garry Brady.[83] He also made some good long-term signings like Gary Speed and Shay Given. The 1997–98 campaign saw Newcastle finish in only 13th place and, despite Dalglish achieving some notable successes during the season (including a 3–2 UEFA Champions League win over Barcelona and an FA Cup final appearance against Arsenal), he was dismissed by Freddie Shepherd after two draws in the opening two games of the subsequent 1998–99 season, and replaced by former Chelsea manager Ruud Gullit.[84][85] One commentator from The Independent has since written, "His 20 months at Newcastle United are the only part of Kenny Dalglish's career that came anywhere near failure".[86]

Celtic

[edit]In June 1999 he was appointed director of football operations at Celtic, with his former Liverpool player John Barnes appointed as head coach.[87] Barnes was dismissed in February 2000 and Dalglish took charge of the first team on a temporary basis.[88] He guided them to the Scottish League Cup final, where they beat Aberdeen 2–0 at Hampden Park. Dalglish was dismissed in June 2000, after the appointment of Martin O'Neill as manager.[89] After a brief legal battle, Dalglish accepted a settlement of £600,000 from Celtic.[90]

Return to Liverpool

[edit]

In April 2009 Liverpool manager Rafael Benítez invited Dalglish to take up a role at the club's youth academy. The appointment was confirmed in July 2009,[91] and Dalglish was also made the club's ambassador.[22] Following Benítez's departure from Liverpool in June 2010, Dalglish was asked to help find a replacement, and in July Fulham's Roy Hodgson was appointed manager.[92]

A poor run of results at the start of the 2010–11 season led to Liverpool fans calling for Dalglish's return as manager as early as October 2010,[93] and with no subsequent improvement in Liverpool's results up to the end of the year (during which time the club was bought by New England Sports Ventures),[94] Hodgson left Liverpool and Dalglish was appointed caretaker manager on 8 January 2011.[95][96] Dalglish's first game in charge was on 9 January 2011 at Old Trafford against Manchester United in the 3rd round of the FA Cup, which Liverpool lost 1–0.[97] Dalglish's first league game in charge was against Blackpool on 12 January 2011; Liverpool lost 2–1.[98] After the game, Dalglish admitted that Liverpool faced "a big challenge".[99]

Shortly after his appointment, Dalglish indicated he would like the job on a permanent basis if it was offered to him,[100] and on 19 January the Liverpool chairman Tom Werner stated that the club's owners would favour this option.[101] On 22 January 2011, Dalglish led Liverpool to their first win since his return, against Wolves at Molineux.[102] After signing Andy Carroll from Newcastle for a British record transfer fee of £35 million and Luis Suárez from Ajax for £22.8 million at the end of January (in the wake of Fernando Torres's sale to Chelsea for £50 million), some journalists noted that Dalglish had begun to assert his authority at the club.[103][104] Following a 1–0 victory against Chelsea at Stamford Bridge in February 2011, described by Alan Smith as "a quite brilliant display in terms of discipline and spirit"[105] and a "defensive masterplan" by David Pleat,[106] Henry Winter wrote, "it can only be a matter of time before he [Dalglish] is confirmed as long-term manager".[107]

On 12 May 2011, Liverpool announced that Dalglish had been given a three-year contract.[108] His first official match in charge was 2–0 defeat to Harry Redknapp's Spurs at Anfield. Dalglish's second stint in charge at Anfield proved controversial at times. The Scot defended Luis Suárez in the wake of the striker's eight-match ban for racially abusing Manchester United defender Patrice Evra when the teams met in October 2011.[109] After the Uruguayan's apparent refusal to shake Evra's hand in the return fixture in February 2012, an apology from both player and manager came only after the intervention of the owners.[110][111]

In February 2012, Dalglish led Liverpool to their first trophy in six years, with victory in the 2011–12 Football League Cup.[112] In the same season he also led Liverpool to the 2012 FA Cup Final where they lost 2–1 to Chelsea. Despite the success in domestic cups, Liverpool finished eighth in the league, their worst showing in the league since 1994, failing to qualify for the Champions League for a third straight season.[113] Following the end of the season, Liverpool dismissed Dalglish on 16 May 2012.[111][114]

In October 2013, Dalglish returned to Liverpool as a non-executive director.[115]

On 13 October 2017, Anfield's Centenary Stand was officially renamed the Sir Kenny Dalglish Stand in recognition of his unique contribution to the club.[116]

Personal life

[edit]

Dalglish has been married to Marina since 26 November 1974.[117] The couple have four children, Kelly, Paul, Lynsey and Lauren. Kelly has worked as a football presenter for BBC Radio 5 Live and Sky Sports.[118] Paul followed in his father's footsteps as a footballer, playing in the Premier League and Scottish Premiership before travelling to the United States to play for the Houston Dynamo in Major League Soccer. He retired in 2008 and became a coach, spending time as head coach of Ottawa Fury FC and Miami FC in the second-division leagues of North America.[119] Dalglish's wife Marina was diagnosed with breast cancer in March 2003,[120] but was treated at Aintree University Hospital in Liverpool and recovered. She later launched a charity to fund new cancer treatment equipment for UK hospitals.[121]

Dalglish was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 1985 New Year Honours for services to football.[122] He was appointed a Knight Bachelor in the 2018 Birthday Honours for services to football, charity and the City of Liverpool.[123] He dedicated the award to former Celtic and Liverpool coaches Jock Stein, Bill Shankly and Bob Paisley stating that he was "Humbled" and "A wee bit embarrassed".[124]

In 2002, Celtic supporters voted for what they considered to be the greatest Celtic XI of all time. Dalglish was voted into the team, which was; Simpson, McGrain, Gemmell, Murdoch, McNeill, Auld, Johnstone, P. McStay, Dalglish, Larsson and Lennox.[125] He was an inaugural inductee to the English Football Hall of Fame the same year,[126] and later also an inaugural inductee to the Scottish Football Hall of Fame in 2004.[127] He is very highly regarded by Liverpool fans, who still affectionately refer to him as King Kenny,[128][129] as do supporters of the Scotland National team from the 70s and 80s when he was a world-class player. In 2006 Liverpool fans voted him top of the fans' poll "100 Players Who Shook the Kop".[130] In 2009, FourFourTwo magazine named Dalglish the greatest striker in post-war British football.[131]

In early April 2020, while in hospital for treatment for an unrelated condition, Dalglish was found to be positive for COVID-19, though asymptomatic.[132]

On 19 December 2023, Dalglish won the BBC Lifetime Achievement Award, BBC Sports Personality of the Year.[133]

Charitable work

[edit]In 2005, Dalglish and his wife founded the charity The Marina Dalglish Appeal to raise money to help treat cancer. Dalglish has participated in a number of events to raise money for the charity, including a replay of the 1986 FA Cup Final.[134] In June 2007 a Centre for Oncology at Aintree University Hospital was opened, after the charity had raised £1.5 million.[135] In 2012, the foundation made a £2 million donation to The Walton Centre which allowed the purchase of a new MRI scanner.[136] Dalglish often competes in the annual Gary Player Invitational Tournament, a charity golfing event which raises money for children's causes around the world.[137] On 1 July 2011, Dalglish was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Ulster, for services to football and charity.[138]

Career statistics

[edit]Club

[edit]| Club | Season | League | National cup[a] | League cup[b] | Europe | Other | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| Celtic | 1968–69 | Scottish Division One |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | 1 | 0 | |

| 1969–70 | Scottish Division One |

2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | 4 | 0 | ||

| 1970–71 | Scottish Division One |

3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1[c] | 0 | 2[d] | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| 1971–72 | Scottish Division One |

31 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 7[c] | 0 | 3[e] | 6 | 53 | 29 | |

| 1972–73 | Scottish Division One |

32 | 21 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 4[c] | 3 | 3[e] | 0 | 56 | 39 | |

| 1973–74 | Scottish Division One |

33 | 18 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 7[c] | 2 | 3[e] | 1 | 59 | 25 | |

| 1974–75 | Scottish Division One |

33 | 16 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 2[c] | 0 | 3[f] | 0 | 51 | 21 | |

| 1975–76 | Scottish Premier Division |

35 | 24 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 5[g] | 3 | 2[d] | 0 | 53 | 32 | |

| 1976–77 | Scottish Premier Division |

35 | 15 | 7 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 2[h] | 1 | – | 54 | 27 | ||

| Total | 204 | 111 | 30 | 11 | 60 | 35 | 28 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 338 | 173 | ||

| Liverpool | 1977–78 | First Division | 42 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 9[c] | 4 | 1[i] | 0 | 62 | 31 |

| 1978–79 | First Division | 42 | 21 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 4[c] | 0 | – | 54 | 25 | ||

| 1979–80 | First Division | 42 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 2[c] | 0 | 1[i] | 1 | 60 | 23 | |

| 1980–81 | First Division | 34 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 9[c] | 1 | 1[i] | 0 | 54 | 18 | |

| 1981–82 | First Division | 42 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 6[c] | 2 | 1[j] | 0 | 62 | 22 | |

| 1982–83 | First Division | 42 | 18 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 5[c] | 1 | 1[i] | 0 | 58 | 20 | |

| 1983–84 | First Division | 33 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 9[c] | 3 | 1[i] | 0 | 51 | 12 | |

| 1984–85 | First Division | 36 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7[c] | 0 | 2[k] | 0 | 53 | 6 | |

| 1985–86 | First Division | 21 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | – | 2[l] | 2 | 31 | 7 | ||

| 1986–87 | First Division | 18 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | – | 2[m] | 0 | 25 | 8 | ||

| 1987–88 | First Division | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 2 | 0 | |||

| 1988–89 | First Division | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | – | 1[n] | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 1989–90 | First Division | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 1 | 0 | |||

| Total | 355 | 118 | 37 | 13 | 59 | 27 | 51 | 11 | 13 | 3 | 515 | 172 | ||

| Career total | 559 | 229 | 67 | 24 | 119 | 62 | 79 | 20 | 29 | 10 | 853 | 345 | ||

- ^ Includes Scottish Cup, FA Cup

- ^ Includes Scottish League Cup, Football League Cup

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Appearance(s) in European Cup

- ^ a b Appearances in Glasgow Cup

- ^ a b c Appearances in Drybrough Cup

- ^ One appearance in Drybrough Cup, two appearances in Glasgow Cup

- ^ Appearances in European Cup Winners' Cup

- ^ Appearances in UEFA Cup

- ^ a b c d e Appearance in FA Charity Shield

- ^ Appearance in Intercontinental Cup

- ^ One appearance in FA Charity Shield, one appearance in Intercontinental Cup

- ^ Appearances in Football League Super Cup

- ^ One appearance in FA Charity Shield, one appearance in Football League Super Cup

- ^ Appearance in Football League Centenary Trophy

International

[edit]| National team | Year | Apps | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland | 1971 | 2 | 0 |

| 1972 | 2 | 1 | |

| 1973 | 9 | 1 | |

| 1974 | 11 | 4 | |

| 1975 | 10 | 2 | |

| 1976 | 6 | 3 | |

| 1977 | 10 | 7 | |

| 1978 | 10 | 3 | |

| 1979 | 9 | 1 | |

| 1980 | 8 | 1 | |

| 1981 | 4 | 1 | |

| 1982 | 8 | 4 | |

| 1983 | 4 | 0 | |

| 1984 | 3 | 2 | |

| 1985 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1986 | 3 | 0 | |

| Total | 102 | 30 | |

Managerial record

[edit]| Team | From | To | Record | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | W | D | L | Win % | ||||

| Liverpool | 30 May 1985 | 21 February 1991 | 307 | 187 | 78 | 42 | 60.9 | [141] |

| Blackburn Rovers | 12 October 1991 | 25 June 1995 | 196 | 103 | 46 | 47 | 52.6 | [142] |

| Newcastle United | 14 January 1997 | 27 August 1998 | 78 | 30 | 22 | 26 | 38.5 | [142] |

| Celtic | 10 February 2000 | 1 June 2000 | 18 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 55.6 | [142] |

| Liverpool | 8 January 2011 | 16 May 2012 | 74 | 35 | 17 | 22 | 47.3 | [142] |

| Total | 673 | 365 | 167 | 141 | 54.2 | — | ||

Honours

[edit]Player

[edit]Celtic[143]

- Scottish Division One/Premier Division: 1971–72, 1972–73, 1973–74, 1976–77

- Scottish Cup: 1971–72, 1973–74, 1974–75,[144] 1976–77; runner-up: 1972–73[citation needed]

- Scottish League Cup: 1974–75;[144] runner-up: 1971–72, 1972–73, 1973–74. 1975–76, 1976–77

- Drybrough Cup: 1974–75;[144][145] runner-up: 1971–72, 1972–73, 1973–74[citation needed]

- Glasgow Cup: 1974–75;[144][146] runner-up: 1975–76[citation needed]

- Football League First Division: 1978–79, 1979–80, 1981–82, 1982–83, 1983–84, 1985–86

- FA Cup: 1985–86

- Football League Cup: 1980–81, 1981–82, 1982–83, 1983–84; runner-up: 1977–78[citation needed]

- Football League Super Cup: 1986[148]

- FA Charity Shield: 1977 (shared),[149] 1979,[150] 1980,[151] 1982,[152] 1986 (shared);[153] runner-up: 1983

- European Cup: 1977–78, 1980–81, 1983–84; runner-up: 1984–85[citation needed]

- European Super Cup: 1977; runner-up: 1978

- Intercontinental Cup runner-up: 1981, 1984

Scotland

Individual

- Scottish Premier Division Top-scorer: 1975–76 (24 goals)

- Ballon d'Or runner-up: 1983[154]

- PFA Team of the Year: 1978-1979, 1979-1980, 1980-1981, 1982-1983, 1983-1984[155]

- PFA Players' Player of the Year: 1982–83[156]

- FWA Footballer of the Year: 1978–79, 1982–83[157]

- Football League 100 Legends

- English Football Hall of Fame (Player): 2002[158]

- Scottish Football Hall of Fame: 2004[159]

- FIFA 100: 2004[160]

- BBC Goal of the Season: 1982–83[161]

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year Lifetime Achievement Award: 2023[133]

- Bleacher Report's 21st Best Footballer Of All Time: 2011[162]

- Scotland's Greatest International Footballer: 2020[163]

- World Soccer Greatest Players of 20th Century: 22nd

Manager

[edit]Liverpool[143]

- Football League First Division: 1985–86, 1987–88, 1989–90

- FA Cup: 1985–86, 1988–89; runner-up: 1987-88, 2011–12[164]

- Football League Cup: 2011–12; runner-up: 1986–87

- Football League Super Cup: 1985–86

- FA Charity Shield: 1986 (shared),[153] 1988,[165] 1989,[166] 1990 (shared)[167]

Blackburn Rovers

Newcastle United

Celtic

Individual

- FWA Tribute Award: 1987[169]

- Premier League Manager of the Season: 1994–95[168]

- Premier League Manager of the Month: January 1994, November 1994[168]

Orders

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of men's footballers with 100 or more international caps

- List of English football championship winning managers

- List of Scotland national football team captains

- List of Scottish football families

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Kenny Dalglish". Barry Hugman's Footballers. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Rollin, Jack (1980). Rothmans football yearbook. London: Queen Anne Press. p. 222. ISBN 0362020175.

- ^ "Scotland U23 player Kenny Dalglish". FitbaStats. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ *"The 100 Best Footballers of All Time". Bleacher Report. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "Ranked! The 100 best football players of all time". FourFourTwo. 5 September 2023. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "Best Liverpool players ever, the top 50". The Telegraph. 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "TBest Scottish Footballers Ever: Here are Scotland's 10 best footballers of all time - according to our readers". The Scotsman. 15 March 2023. Archived from the original on 17 February 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "Ranked! The 25 best British players of all time". FourFourTwo. 14 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 February 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Dalglish & Winter 2010, p. 3

- ^ "Liverpool manager Kenny Dalglish through the years: in pictures". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "In pictures: Kenny Dalglish returns to the Glasgow streets where he grew up to mark the publication of a new book celebrating his life". Daily Record. 22 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ a b c My School Sport: Kenny Dalglish Archived 12 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Daily Telegraph (12 April 2006) Retrieved on 18 June 2009

- ^ "Hall of Fame Kenny Dalglish". International Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Lomax, Andrew (14 February 2008) Kenny Dalglish backs Scottish youngsters The Daily Telegraph (London) Retrieved on 18 June 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Player profile". lfchistory.net. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Macpherson 2007, p. 224

- ^ "Now You Know: Kenny Dalglish debuted for Celtic against Hamilton". Evening Times. 18 March 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "Games Involving Dalglish, Kenny in season 1969/1970". FitbaStats. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish: Hillsborough families are magnificent". Liverpool Echo. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Dalglish hits six in testimonial". The Glasgow Herald. 15 May 1971. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Smith, Andrew (3 March 2021). "Kenny Dalglish at 70: Why Celtic greatness should be more than a footnote to Liverpool glories". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Dalglish, Kenny". FitbaStats. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Archer, Ian (5 May 1975). "To Celtic cup no. 24, to Airdrie our thanks". The Glasgow Herald. p. 18. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "Remembering Jock Stein". BBC Sport. 6 September 2005. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "The Immortal Jock Stein and the A74 Highway Crash". 28 April 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Benitez opens talks with Dalglish". BBC Sport. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ Macpherson 2007, p. 279

- ^ a b "Kenny DALGLISH - Biography (Part 1) of Career at Liverpool. - Liverpool FC". Sporting Heroes. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Games for the 1977-1978 season - LFChistory - Stats galore for Liverpool FC!". www.lfchistory.net. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Squad of Liverpool 1977-78 First Division | BDFutbol". www.bdfutbol.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Dalglish keeps Reds on top". UEFA.com. 10 May 1978. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Previous Winners – Footballer of the year – Football Writers' Association". Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Liverpool career stats for Kenny Dalglish - LFChistory - Stats galore for Liverpool FC!". www.lfchistory.net. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Games for the 1980-1981 season - LFChistory - Stats galore for Liverpool FC!". www.lfchistory.net. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Rush, Dalglish voted best British strike duo". The Independent. London. 6 March 1999. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Murray, Scott; Smyth, Rob (24 April 2009). "The Joy of Six: great strike partnerships". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Benammar, Emily (27 April 2008). "PFA Player of the Year winners 1974–2007". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "player profile-KENNY DALGLISH". lfchistory.net. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Remembering Joe Fagan". Liverpool FC. 12 March 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Times, The Brussels. "Remembering the 1985 Heysel Stadium disaster in Brussels". www.brusselstimes.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Appearances for the 1985-1986 season - LFChistory - Stats galore for Liverpool FC!". www.lfchistory.net. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Chelsea 0–1 Liverpool, First Division, May 3, 1986". Daily Mirror. London. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Liverpool 1–0 Derby County". LFCHistory.net. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ "Liverweb all-time playing records". Liverweb. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Kenny Dalglish | Scotland | Scottish FA". www.scottishfa.co.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "World Cup 1974 finals". RSSSF.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "eu-football.info". eu-football.info. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "eu-football.info". eu-football.info. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Scotland 3–2 Holland, World Cup finals group stage, June 11, 1978". Daily Mirror. London. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Scotland: Stein, Narey, Brazil & being a cartoon character". BBC Sport. 12 June 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish | Scotland's record goalscorer | icons.com". Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Grahame, Ewing (8 October 2008). "George Burley backs Darren Fletcher to beat Kenny Dalglish's Scotland cap record". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "The Kenny Dalglish file". BBC Sport. 27 August 1998. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Tait, Jim (2023). Scotland at 150. A century and a half of international football. Lerwick: Jicks Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-3999-4506-6.

- ^ "Scotland 3 Luxembourg 0". The Glasgow Herald. 13 November 1986. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Kenny Dalglish at the Scottish Football Association

- ^ Bevan, Chris; Barder, Russell (23 January 2009). "When Dalglish did the Double". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ FA Cup Final 1988 Archived 9 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine FA-Cup Finals. Retrieved 18 June 2009

- ^ Smith, Rory (17 April 2009). "Top 10 classic FA Cup semi-finals". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Birchall, Jon (14 January 2011). "Remembering 4–4 draw between Everton FC and Liverpool FC". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ "The day from which Liverpool have never recovered". ESPN. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Louise (14 January 2011). "The game that forced Kenny Dalglish to resign as Liverpool manager". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Winter, Henry (17 October 2011). "Hillsborough disaster: release of papers is long overdue". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Roper, Matt (15 April 2019). "Kenny Dalglish carried Liverpool after Hillsborough - & it nearly destroyed him". The Mirror. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Association, Press (4 March 2021). "King Kenny admired as 'one of the greatest of all time'". This Is Anfield. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Herbert, Ian (17 May 2012). "King Kenny loses grip on poisoned chalice". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Dalglish breaks disaster silence". BBC Sport. 3 March 2009. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (27 April 2011). "Liverpool MP Steve Rotheram tables parliamentary motion to get Kenny Dalglish knighted". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ FC, Blackburn Rovers (14 May 2020). "Champions: Sir Kenny Dalglish". Blackburn Rovers FC. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Magee, Will (13 December 2016). "Game Changers: Blackburn Rovers and Jack Walker's Millions". VICE. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Singleton, Ian (9 April 2012). "How Kenny Dalglish turned a six-game losing run into glory". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "30 years of the Premier League: How 'left field' Rovers made their mark". Lancashire Telegraph. 15 August 2022. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Blackburn Rovers Archived 11 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine FA Premier League. Retrieved 18 June 2009

- ^ "Blackburn Rovers owner dies". BBC Sport. 18 August 2000. Archived from the original on 6 April 2003. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Kissane, Sinead (19 August 2002) Keane tells of Dalgish fury Archived 10 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine RTÉ. Retrieved 18 June 2009

- ^ Field, Pippa (10 October 2018). "Tim Flowers' journey from England duty to non-league management: 'It is grassroots but it doesn't matter to me, it's football'". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Guy Hodgson (25 March 1994). "Football: Batty effect takes over at Blackburn: Guy Hodgson on the best and worst buys of the season". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "PL30: Were Shearer and Sutton the best-ever partnership?". www.premierleague.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "1994/95". www.premierleague.com. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ FC, Blackburn Rovers (14 May 2020). "Champions: Sir Kenny Dalglish". Blackburn Rovers FC. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Shaw, Phil (21 August 1996). "Dalglish and Blackburn part company". The Independent. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "The Kenny Dalglish story". The Guardian. 11 February 2000.

- ^ "Dual role for Dalglish Golf is part of the job at Ibrox". The Herald. Glasgow. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ "KENNY'S BLUES MOVIE; Dalglish video sets up Seb deal". Sunday Mail. Glasgow. 17 November 1996. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via TheFreeLibrary.com.

- ^ "The big issues at Newcastle". 12 January 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Newcastle United - 1996/97 Season". nufc-history.co.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Ryder, Lee (10 November 2019). "Asprilla: How Dalglish destroyed The Entertainers". Chronicle Live. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Newcastle United - 1997/98 Season". nufc-history.co.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Sport: Football Gullit named Newcastle boss". BBC Sport. 27 August 1998. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ Rich, Tim (1 May 2011). "The chief problem for Dalglish on Tyneside was that he wasn't Keegan". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Dalglish back at Parkhead". BBC Sport. 10 June 1999. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ "Barnes sacked as Dalglish holds the fort". The Guardian. 10 February 2000. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ Forsyth, Roddy (30 June 2000). "Dalglish hits out over messy Celtic divorce". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Dalglish wins £600,000 claim against Celtic". The Daily Telegraph. London. 15 December 2000. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "Dalglish makes Liverpool return". BBC Sport. 4 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ "Roy Hodgson leaves Fulham to become Liverpool manager". BBC Sport. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Hunter, Andy (4 October 2010). "Spectre of Kenny Dalglish hovers over Roy Hodgson at Liverpool". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ "Liverpool takeover completed by US company NESV". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Ingle, Sean (8 January 2011). "Liverpool let Roy Hodgson go – and appoint Kenny Dalglish as caretaker". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Roy Hodgson exits Liverpool & Kenny Dalglish takes over". BBC Sport. 8 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ "Man Utd 1–0 Liverpool". BBC Sport. 9 January 2011. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ Winter, Henry (12 January 2011). "Blackpool 2 Liverpool 1: match report". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Hunter, Andy (13 January 2011). "Liverpool face 'big challenge' after Blackpool defeat, says Kenny Dalglish". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Winter, Henry (10 January 2011). "Kenny Dalglish admits he would be 'delighted' to become the permanent Liverpool manager". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Smith, Rory (20 January 2011). "Liverpool hope to compromise with Ajax over Luis Suárez". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ White, Duncan (22 January 2011). "Wolverhampton Wanderers 0 Liverpool 3: match report". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Hunter, Andy (2 February 2011). "Kenny Dalglish moves towards permanent manager's role at Liverpool". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Winter, Henry (1 February 2011). "Kenny Dalglish loses Fernando Torres but finds crown princes in Andy Carroll and Luis Suárez". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Smith, Alan (7 February 2011). "Fernando Torres's substitution the ultimate accolade to stubborn Liverpool at Stamford Bridge". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Pleat, David (6 February 2011). "Chelsea big hitters stifled by Kenny Dalglish's defensive masterplan". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ Winter, Henry (6 February 2011). "Chelsea 0 Liverpool 1: match report". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ "Kenny signs three-year deal". Liverpool F.C. 12 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Sport Stuff, PA (2022). "On this day in 2011 – Luis Suarez charged with racially abusing Patrice Evra".

- ^ Roan, Dan (13 February 2012). "Handshake: Suarez and Dalglish apologise after owners intervene". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Kenny Dalglish sacked over Luis Suarez row – Sir Alex Ferguson". BBC Sport. 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Cardiff City 2 Liverpool 2; Liverpool win on penalties". The Daily Telegraph. London. 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ Panja, Tariq (17 May 2012). "Liverpool Fires Dalglish After Worst League Finish in 18 Years". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish sacked as Liverpool manager". BBC Sport. 16 May 2012. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish returns to Liverpool on board of directors". BBC Sport. 4 October 2013. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Liverpool FC officially unveil the Kenny Dalglish Stand". Liverpool F.C. 13 October 2017. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ @laurendalglish (26 November 2014). "Lauren Dalglish congratulates parents on 40th wedding anniversary" (Tweet). Retrieved 26 November 2014 – via Twitter.

- ^ Winter, Henry (23 December 2017). "Kelly Cates interview: I've felt Hillsborough pain differently since becoming a mother". The Times. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Kaufman, Michelle (25 January 2018). "Miami FC has a new coach. It's a name soccer fans will recognize". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Dalglish's wife tells of her cancer fight". The Scotsman. 25 December 2003. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Joshua (28 May 2016). "Kenny and Marina Dalglish unveil new breast cancer scanner at Aintree Hospital". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ a b "No. 49969". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1984. p. 13.

- ^ a b "No. 62310". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 June 2018. p. B2.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish honoured with knighthood". www.liverpoolfc.com. Liverpool FC. 8 June 2018. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Jinky best-ever Celtic player". BBC Sport. 9 September 2002. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Stanley, Anton (4 March 2021). "KING Liverpool legend Sir Kenny Dalglish was a 'genius' moulded by Jock Stein at Celtic, loved by Manchester United icon George Best, and is Anfield's greatest ever player". talkSPORT. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Dinner 2004". Scottish Football Museum. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish & knighthood: Why do Liverpool fans insist on calling him 'King' and not 'Sir'?". Goal. 17 November 2018. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "100 PWSTK – THE DEFINITIVE LIST". Liverpool F.C. 8 October 2006. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ Carroll, James (24 January 2010). "Dalglish named the greatest". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish latest footballing great to test positive for coronavirus". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Sports Personality of the Year: Sir Kenny Dalglish wins Lifetime Achievement award". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Paul (1 May 2006). "Reds leave it late to win Replay 86". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "The Marina Dalglish Appeal – About Us". The Marina Dalglish Appeal.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "New scanner arrives at hospital thanks to £2m donation from the Marina Dalglish Appeal". The Walton Centre NHS Trust. Retrieved 14 November 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Gary Player Invitational Returns to Wentworth". Gary Player.com. 27 April 2006. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Sutton, John (2 July 2011). "Liverpool FC manager Kenny Dalglish awarded honorary degree". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Dalglish, Kenny". FitbaStats. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Strack-Zimmermann, Benjamin. "Kenny Dalglish". national-football-teams.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ "Manager profile: Kenny Dalglish". LFCHistory.net. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d "Managers: Kenny Dalglish". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Philip, Robert (2011). "12. Kenny Dalglish MBE". Scottish Sporting Legends. Mainstream Publishing Company (Edinburgh) Ltd. ISBN 9781780571669. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d Games involving Dalglish, Kenny in season 1974/1975 Archived 2 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Celtic FitbaStats

- ^ Drybrough tonic from 'Old Firm' Archived 20 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Evening Times, 5 August 1974, via The Celtic Wiki

- ^ Old Firm turn on a final classic Archived 20 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Glasgow Herald, 12 May 1975, via The Celtic Wiki

- ^ "About the site". lfchistory.net. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ "Match details from Everton - Liverpool played on 30 September 1986". LFChistory. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ "Match details from Liverpool – Manchester United played on 13 August 1977 – LFChistory". Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Match details from Liverpool – Arsenal played on 11 August 1979 – LFC history". Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Charity Shield returns to Anfield". Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "1982/83 Charity Shield Liverpool v Tottenham Hotspur". Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Match details from Liverpool – Everton played on 16 August 1986". Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Ballon d'Or Winners". About.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Lynch, Tony (1995). The Official P.F.A. Footballers Heroes. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-179135-3.

- ^ "England Player Honours – Professional Footballers' Association Players' Players of the Year". England Football Online. 19 June 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "FWA FOOTBALLER OF THE YEAR AWARD". footballwriters. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Kenny Dalglish". nationalfootballmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Inductees 2004". scottishfootballhalloffame.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Davies, Christopher (5 March 2004). "Pele open to ridicule over top hundred". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Pye, Steven (9 September 2014). "The 10 goals of the season in the 1980s". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "100bestfootballers". bleacherreport.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "scotlands-greatest-international". www.scottishfa.co.uk/. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Match Details: Liverpool 1 Chelsea 2". LFCHistory.net. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Match details from Liverpool – Wimbledon played on 20 August 1988 – LFC history". Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Match details from Liverpool – Arsenal played on 12 August 1989 – LFC history". Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Match details from Liverpool – Manchester United played on 18 August 1990 – LFC history". Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "Manager profile: Kenny Dalglish". Premier League. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ "FWA TRIBUTE AWARD". Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Kelly, Stephen (1993). Dalglish. Headline Book Publishing; New edition (19 August 1993). ISBN 0-7472-4124-4.

- Dalglish, Kenny; Winter, Henry (2010). My Liverpool Home. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-4447-0419-8.

- Macpherson, Archie (2007). Jock Stein: The Definitive Biography. Highdown; New Ed edition (18 May 2007). ISBN 978-1-905156-37-5.

External links

[edit]- Kenny Dalglish on Twitter

- Kenny Dalglish at the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame

- Kenny Dalglish at the Scottish Football Association

- Kenny Dalglish management career statistics at Soccerbase

- Official past players at Liverpool fc.tv Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- English Football Hall of Fame Profile at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 March 2015)

- LFCHistory.net Player profile. Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- LFCHistory.net Manager profile. Archived 2 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- Premier League manager profile. Archived 26 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ESPN Profile at the Wayback Machine (archived 15 May 2011)

- Kenny Dalglish – FIFA competition record (archived)

- Kenny Dalglish – UEFA competition record (archive)

- 1951 births

- Living people

- Footballers from Glasgow

- Scottish men's footballers

- Men's association football forwards

- Cumbernauld United F.C. players

- Celtic F.C. players

- Liverpool F.C. players

- Scottish Junior Football Association players

- Scottish Football League players

- English Football League players

- Scottish league football top scorers

- UEFA Champions League–winning players

- English Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Scottish Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Scotland men's under-23 international footballers

- Scotland men's international footballers

- 1974 FIFA World Cup players

- 1978 FIFA World Cup players

- 1982 FIFA World Cup players

- FIFA Men's Century Club

- FIFA 100

- Men's association football player-managers

- Scottish football managers

- Liverpool F.C. managers

- Blackburn Rovers F.C. managers

- Newcastle United F.C. managers

- Celtic F.C. managers

- English Football League managers

- Premier League managers

- Scottish Premier League managers

- Association football people awarded knighthoods

- Knights Bachelor

- Members of the Order of the British Empire

- BBC Sports Personality Lifetime Achievement Award recipients