James Kim

James Kim | |

|---|---|

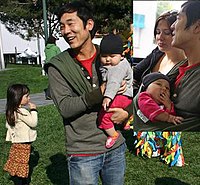

Kim with his two daughters | |

| Born | August 9, 1971 |

| Died | December 4, 2006 (aged 35) Josephine County, Oregon, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Technology analyst |

| Spouse | Kati Kim |

| Children | Penelope, Sabine |

| Parent | Spencer H. Kim |

James Kim (August 9, 1971 – December 4, 2006) was an American television personality and technology analyst for the former TechTV international cable television network, reviewing products for shows including The Screen Savers, Call for Help, and Fresh Gear. At the time of his death he was working as a senior editor of MP3 and digital audio for CNET, where he wrote more than 400 product reviews. He also cohosted a weekly video podcast for CNET's gadget blog, Crave, and a weekly audio podcast, The MP3 Insider (both podcasts were cohosted with Veronica Belmont).

Kim's disappearance, death, and his family's ordeal made them the subject of a brief, but intense period of news coverage in December 2006.

Early life

[edit]Kim graduated from Ballard High School in Louisville, Kentucky,[1] in 1989 and from Oberlin College in Ohio in 1993 where he double-majored in Government and English and played for the varsity lacrosse team.[2] The son of Spencer H. Kim,[3] an aerospace company executive and internationalist,[4] he and his wife, Kati, owned two retail stores in San Francisco, California.

Career

[edit]Kim was most widely known as a television personality on the international cable network TechTV, where he was a senior technology analyst for TechTV Labs. He made frequent appearances testing new products for shows including The Screen Savers, Call for Help, Fresh Gear, and AudioFile. He was best known for his "Lab Rats" segments, in which he reviewed the latest electronic gadgets. After leaving TechTV, he became a senior editor for CNET, a technology trade journal, which he had joined in 2004. He wrote product reviews and co-hosted a weekly podcast for CNET's gadget blog, Crave.[5] Prior to working for TechTV, he had been a legal assistant at law firms in New York and France; a media relations assistant for baseball's American League; and a script reader for Miramax Films.

Snowbound

[edit]After spending the 2006 Thanksgiving holiday in Seattle, Washington, the Kim family (James, Kati, and their two daughters, 4-year old Penelope and 7-month old Sabine) set out for their home in San Francisco. On Saturday, November 25, 2006, having left Portland, Oregon, on their way to Tu Tu' Tun Lodge, a resort located near Gold Beach, Oregon, they apparently missed a turnoff from Interstate 5 to Oregon Route 42, a main route to the Oregon Coast. Instead of returning to the exit, they consulted a highway map and picked a secondary route along Bear Camp Road that skirted the Wild Rogue Wilderness, a remote area of southwestern Oregon.[6]

After encountering heavy snow at high elevation on Bear Camp Road, the Kims backtracked and ventured onto BLM Road 34-8-36 (North Fork Galice Creek Road) (42°34′28″N 123°45′01″W / 42.5744°N 123.7504°W), a paved logging road supervised by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) thinking that could be an option. A road gate intended to prevent such mistakes was open despite BLM rules requiring that it be closed. Media outlets reported that vandals had cut a lock on it, but a subsequent investigation showed that BLM employees had left it open to avoid trapping local hunters and others who might have ventured past it.

[7]

After 23 miles of slow travel along BLM Road 34-8-36, the Kims stopped at about 1:00 am on November 26 because of fatigue and bad weather (42°41′19″N 123°46′38″W / 42.6885°N 123.7773°W). As more snow fell around their immobilized Saab 9-2X station wagon, they kept warm by running the engine. When it ran out of fuel, they made a campfire of dried wood and magazines. Later, they burned the car's tires to signal rescuers. Search efforts began shortly after November 30, when Kim's coworkers filed a missing persons report with the San Francisco Police Department.[8] After investigators learned that the Kims used their credit card at a local restaurant, search and rescue teams, including local and state police, more than 80 civilian volunteers, the Oregon Army National Guard and several helicopters hired by Spencer spent several days looking for them along area highways and roads, to no avail.

On December 2, Kim left his family to look for help, wearing tennis shoes, a jacket, and light clothing. He believed the nearest town (Galice) was located four miles away after studying a map with Kati.[9] He promised her he would turn back the same day if he failed to find anyone, but he did not return.[10] He backtracked about 11 miles down BLM Road 34-8-36 before leaving the roadway and electing to follow a ravine northeast down the mountain.

Search

[edit]Although the Kims had a cellular phone with them, their remote location in the mountains was out of range of the cellular network, rendering the phone unusable for voice calls. Despite it being so, it would play a key role in their rescue. Cell phone text messages may go through even when there appears to be no signal, in part because text messaging is a store-and-forward service. Two Edge Wireless engineers, Eric Fuqua and Noah Pugsley, contacted search and rescue authorities offering their help in the search. On Saturday, December 2, they began searching through the data logs of cell sites, trying to find records of repeaters to which the Kims' cell phone may have connected. They discovered that on November 26, 2006, at around 1:30am, it made a brief automatic connection to a cell site near Glendale, Oregon, and retrieved two text messages. Temporary atmospheric conditions, such as tropospheric ducting, can briefly allow radio communications over larger distances than normal. Through the data logs, the engineers determined that the cell phone was in a specific area west of the cellular tower. They then used a computer program to determine which areas in the mountains were within a line-of-sight to the cellular tower. This narrowed the search area tremendously, and finally focused rescue efforts on Bear Camp Road.[11]

On the afternoon of December 4, John Rachor, a local helicopter pilot unaffiliated with any formal search effort, spotted Kati, Penelope, and Sabine walking on a remote road. After he radioed their position to authorities, they were airlifted out of the area and transferred to a nearby hospital.[12]

Law enforcement officials said that the discovery of the cellphone connection, and the subsequent analysis of the log data, was the critical breakthrough that ultimately resulted in Kati, Penelope, and Sabine's rescue by helicopter.[11]

Death

[edit]Officials continued to search for Kim, at one point finding clothing that he had discarded along the way in the likely belief that he was too hot; paradoxical undressing is a symptom of hypothermia. Optimistic Oregon officials stated, "These were placed with our belief that little signs are being left by James for anyone that may be trying to find him so that they can continue into the area that he's continuing to move in."[13]

On Wednesday, December 6 at 12:03 p.m., Kim's body was found in Big Windy Creek.[14][15] (42°38′44″N 123°43′25″W / 42.645575°N 123.723575°W) Lying on his back in one to two feet of icy water, he was fully clothed and had been carrying a backpack which contained his identification documents, among other miscellaneous items.[16] He had walked about 16.2 miles (26 km) from the car to that point, and was only a mile from Black Bar Lodge, which, although closed for the winter, was fully stocked at the time. An autopsy revealed that he had died of hypothermia and that his body had suffered no incapacitating physical injuries. The medical examiner who performed the autopsy guessed that he had died roughly two days after leaving the car.[16][17]

Route

[edit]Because of Kim's background as a technology analyst, observers speculated that his family had used online mapping to find their route.[18] However, Kati told state police that they had used a paper road map,[19] an account supported by the Oregon State Police, which reported that they had used an official State of Oregon highway one.[20] Kati later recounted that, after they had been stuck for four days and were studying it for help, both she and Kim noticed that a box in the corner bore the message: "Not all Roads Advisable, Check Weather Conditions".[21]

Bear Camp Road is lightly used between October and April, even by local residents, because of its difficult terrain, spotty maintenance, steep drop offs, and often inclement weather.[22] As they drove along the road, the Kims passed three prominent warning signs that state: "Bear Camp Road May Be Blocked By Snowdrifts".[23] Kati later told police that they had noticed only one.

Media

[edit]The Kims' ordeal became a lead story on most major U.S. news networks. In the hours after Kim's body was found, it became the highest rated article on MSNBC.com with a reported one million page views. CNN.com reported 755,000 views of its coverage of the story.[24] Within a week, the Kims appeared on the cover of People magazine.

Newspapers in the region, led by The Oregonian and the San Francisco Chronicle, devoted heavy coverage to the events and their aftermath. The Oregonian was awarded the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for a distinguished example of local reporting of breaking news, presented in print or online or both, for their coverage of the Kims' story.[25][26] The staff of The Oregonian was lauded for "its skillful and tenacious coverage of a family missing in the Oregon mountains, telling the tragic story both in print and online".

On January 6, 2007, The Washington Post published an op-ed article written by Kim's father, Spencer H. Kim, criticizing various government entities that had in his estimation played roles in his son's death. He blamed the BLM for not locking the gate to the logging road, privacy laws that he claimed had delayed the start of search and rescue efforts, local authorities for "confusion, communication breakdowns and failures of leadership" during the search, and the Federal Aviation Administration for not keeping media aircraft out of the search area.[27]

On February 18, 2007, a memorial service was held for Kim at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.[28]

On September 12, 2007, Kati gave an exclusive interview of the ordeal to UK blogging site DollyMix.[29]

In December 2009, Kati, Penelope, and Sabine made a surprise appearance at a Christmas party being held by the membership of Josephine County Search and Rescue.[30]

In February 2011, the television show 20/20 aired a special 2-hour episode, "The Wrong Turn", which included interviews with Kati.[31]

In September 2011, the television show 20/20 aired a second special 2-hour episode, "The Sixth Sense", which depicted the same story as in "The Wrong Turn".[31]

On August 27, 2017, the television show SOS: How to Survive aired a 1-hour episode, "Trapped in a Blizzard", which depicted the Kims' story with survival tips on how to survive in a similar situation [32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Missing father graduated from high school in Louisville". Associated Press. December 6, 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-11-02. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Janie Har; Larry Bingham (December 7, 2006). "James Kim's love for family, friends left lasting impression with many". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Julia Prodis Sulek (December 7, 2006). "Deputy says Kim may have been dead only hours when found". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on December 12, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "Mr. Spencer H. Kim, Chairman, CBOL Corporation". Pacific Council on International Policy. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ CNET Welcome to Crave, 15 February 2007, retrieved 2021-05-26

- ^ Barnard, Jeff (December 8, 2006). "Kim died near remote fishing lodge". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ Sleeth, Peter (2006-12-14). "BLM left gate open on road to Kims' fate". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on 2007-02-13. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ "SFPD:Missing Persons:Kim Family". San Francisco Police Department. 2006-11-30. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ Peter Fimrite; Marisa Lagos (December 7, 2006). "Kims thought they were only 4 miles from help". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ David R. Anderson (December 4, 2006). "Update: Mom, daughters found; dad still missing". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ^ a b Lloyd Vries (December 6, 2006). "Tragic End To Search For Missing Dad". CBS News. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ "Video: Rescuers find Kim family members; search continues for editor". CNet Networks. Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ "Video: Searchers: We will find James Kim". CNET Networks. Archived from the original on 2013-01-19. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ^ Alex Johnson; Alan Boyle; Peter Alexander; Kevin Tibbles; Susan Siravo; Traci Grant (2006-12-06). "Distraught rescue crews come up just short". NBC News.

- ^ "Body of Missing San Francisco Dad Found in Oregon". Fox News. 2006-12-06.

- ^ a b "James Kim died of hypothermia, autopsy reveals". CNET Networks. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ Jeff Barnard (2006-12-07). "Autopsy: Missing man died of hypothermia". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2006-12-16. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ Leslie Fulbright (December 8, 2006). "Maps: Internet travel directions need to be checked carefully". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ Jeff Barnard (December 6, 2006). "Missing San Francisco man found dead". Corvallis Gazette-Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "Update: Information Discussed During December 6 10 a.m. Media Briefing on Search for James Kim". Oregon State Police. December 6, 2006. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "In Kati Kim's own words". Medford Mail Tribune. January 19, 2007. Archived from the original on February 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- ^ Jaxon van Derbeken; Marisa Lagos (December 6, 2006). "Missing dad leaving clothing and map markers / Kim family initiates dropping of care packages". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ Drew Griffin (December 12, 2006). "Warning signs marked Kim family's journey". CNN. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Garofoli, Joe (December 7, 2006). "A Family's Tragedy / Gripping Story: It was tracked by millions". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ 2007 Pulitzer Prize award announcement from pulitzer.org Archived 19 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael Walden (April 16, 2007). "Oregonian wins Pulitzer Prize for breaking news coverage". blog.oregonlive.com.

- ^ Kim, Spencer H. (January 6, 2007). "Lessons In My Son's Death". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "Man honored for fatal bid to save family". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ "Kati Kim breaks her silence to tell a story of survival". dollymix. September 23, 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007.

- ^ "Searching with compassion, surviving with grace". The Oregonian. December 18, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ a b George Rede (February 4, 2011). "Kati Kim's story of surviving southern Oregon ordeal airs Feb. 11". The Oregonian.

- ^ "Trapped in a Blizzard". The Weather Channel. August 27, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Google Earth Community Archived 2008-01-27 at the Wayback Machine View the area with Google Earth, with waypoints marked includes timeline of events.

- Press Conference Video, December 4, 2006 at archive.today (archived 2012-07-20)

- Satellite re-routed at archive.today (archived 2013-01-20)

- Obituary in the Herald and News

- 1971 births

- 2000s missing person cases

- 2006 deaths

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- Accidental deaths in Oregon

- American bloggers

- American people of Korean descent

- American technology writers

- Television personalities from San Francisco

- Ballard High School (Louisville, Kentucky) alumni

- CNET

- Deaths from hypothermia

- Formerly missing people

- Missing person cases in Oregon

- Oberlin College alumni

- TechTV people

- Television personalities from Louisville, Kentucky

- Writers from Louisville, Kentucky

- Writers from San Francisco

- Villanova University alumni