Kariba Dam

| Kariba Dam | |

|---|---|

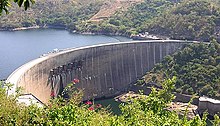

The dam as seen from Zimbabwe | |

| Location | Zambia Zimbabwe |

| Coordinates | 16°31′20″S 28°45′42″E / 16.52222°S 28.76167°E |

| Construction began | 1955 |

| Opening date | 1959 |

| Construction cost | US$480 million |

| Owner(s) | Zambezi River Authority |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Arch dam |

| Impounds | Zambezi River |

| Height | 128 m (420 ft) |

| Length | 579 m (1,900 ft) |

| Width (crest) | 13 metres (43 ft) |

| Width (base) | 24 metres (79 ft) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lake Kariba |

| Total capacity | 180 km3 (150,000,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Catchment area | 663,000 km2 (256,000 sq mi) |

| Surface area | 5,400 km2 (2,100 sq mi) |

| Maximum length | 280 km (170 mi) |

| Maximum water depth | 97 m (318 ft) |

| Power Station | |

| Turbines | North: 4 x 150 MW (200,000 hp), 2 x 180 MW (240,000 hp) Francis-type South: 6 x 125 MW (168,000 hp), 2 x 150 MW (200,000 hp) Francis-type |

| Installed capacity | North: 960 MW South: 1,050 MW Total: 2,010 MW |

| Annual generation | 6,400 GWh (23,000 TJ) |

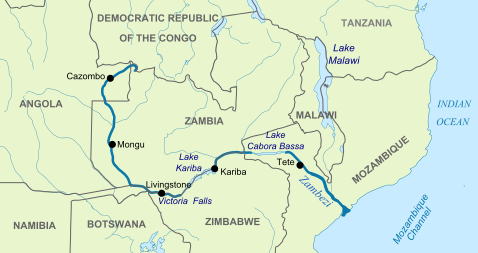

The Kariba Dam is a double curvature concrete arch dam in the Kariba Gorge of the Zambezi river basin between Zambia and Zimbabwe. The dam stands 128 metres (420 ft) tall and 579 metres (1,900 ft) long.[1] The dam forms Lake Kariba, which extends for 280 kilometres (170 mi) and holds 185 cubic kilometres (150,000,000 acre⋅ft) of water.

Construction

[edit]The dam was constructed on the orders of the Government of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, a 'federal colony' within the British Empire. The double curvature concrete arch dam was designed by Coyne et Bellier and constructed between 1955 and 1959 by Impresit of Italy[2] at a cost of $135,000,000 for the first stage with only the Kariba South power cavern. Final construction and the addition of the Kariba North Power cavern by Mitchell Construction[3] was not completed until 1977, due to largely political problems, for a total cost of $480,000,000. During construction, 86 construction workers lost their lives.[2][4]

The dam was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother on 17 May 1960.[5][6]

Power generation

[edit]The Kariba Dam supplies 2,010 megawatts (2,700,000 hp) of electricity to parts of both Zambia (the Copperbelt) and Zimbabwe and generates 6,400 gigawatt-hours (23,000 TJ) per annum. Each country has its own power station on the north and south bank of the dam, respectively. The south station belonging to Zimbabwe has been in operation since 1960 and had six generators of 125 megawatts (168,000 hp) capacity each for a total of 750 megawatts (1,010,000 hp).[7][8]

On November 11, 2013 it was announced by Zimbabwe's Finance Minister, Patrick Chinamasa that capacity at the Zimbabwean (South) Kariba hydropower station would be increased by 300 megawatts. The cost of upgrading the facility has been supported by a $319m loan from China. The deal is a clear example of Zimbabwe's "Look East" policy, which was adopted after falling out with Western powers.[9] Construction on the Kariba South expansion began in mid-2014 and was initially expected to be complete in 2019.[10]

In March 2018, president Emmerson Mnangagwa commissioned the completed expansion of Kariba South Hydroelectric Power Station. The addition of two new 150 megawatts (200,000 hp) turbines raised capacity at this station to 1,050 megawatts (1,410,000 hp). The expansion work was done by Sinohydro, at a cost of US$533 million. Work started in 2014, and was completed in March 2018.[11]

The north station belonging to Zambia has been in operation since 1976, and has four generators of 150 megawatts (200,000 hp) each for a total of 600 megawatts (800,000 hp); work to expand this capacity by an additional 360 megawatts (480,000 hp) to 960 megawatts (1,290,000 hp) was completed in December 2013. Two additional 180 MW generators were added.[12][13][14]

Location

[edit]

The Kariba Dam project was planned and carried out by the Government of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The Federation was often referred to as the Central African Federation (CAF). The CAF was a 'federal colony' within the British Empire in southern Africa that existed from 1953 to the end of 1963, comprising the former self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia and the former British protectorates of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Northern Rhodesia had decided earlier in 1953 (before the Federation was founded) to build a dam within its territory, on the Kafue River, a major tributary of the Zambezi. It would have been closer to Northern Rhodesia's Copperbelt, which was in need of more power. This would have been a cheaper and less grandiose project, with a smaller environmental impact. Southern Rhodesia, the richest of the three, objected to a Kafue dam and insisted that the dam be sited instead at Kariba. Also, the capacity of the Kafue dam was much lower than that at Kariba.[15] Initially, the dam was managed and maintained by the Central African Power Corporation.[16] The Kariba Dam is now owned and operated by the Zambezi River Authority,[17] which is jointly and equally owned by Zimbabwe and Zambia.[18]

Since Zambia's independence, three dams have been built on the Kafue River: the Kafue Gorge Upper Dam, Kafue Gorge Lower Dam and the Itezhi-Tezhi Dam.[19]

Environmental impacts

[edit]Population displacement and resettlement

[edit]The creation of the reservoir forced resettlement of about 57,000 Tonga people living along the Zambezi on both sides.[20]

There are many different perspectives on how much resettlement aid was given to the displaced Tonga. British author David Howarth described the efforts in Northern Rhodesia:

"Everything that a government can do on a meagre budget is being done. Demonstration gardens have been planted, to try to teach the Tonga more sensible methods of agriculture, and to try to find cash crops that they can grow. The hilly land has been plowed in ridge contours to guard against erosion. In Sinazongwe, an irrigated garden has grown a prodigious crop of pawpaws, bananas, oranges, lemons, and vegetables, and shown that the remains of the valley could be made prolific if only money could be found for irrigation. Cooperative markets have been organized, and Tonga are being taught to run them. Enterprising Tonga have been given loans to set themselves up as farmers. More schools have been built than the Tonga ever had before, and most of the Tonga are now within reach of dispensaries and hospitals."[21]

Anthropologist Thayer Scudder, who has studied these communities since the late 1950s, wrote:

"Today, most are still 'development refugees'. Many live in less-productive, problem-prone areas, some of which have been so seriously degraded within the last generation that they resemble lands on the edge of the Sahara Desert."[22]

American writer Jacques Leslie, in Deep Water (2005), focused on the plight of the people displaced by Kariba Dam, and found the situation little changed since the 1970s. In his view, Kariba remains the worst dam-resettlement disaster in African history.[23]

Basilwizi Trust

[edit]

In an effort to regain control of their lives, the local people who were displaced by the Kariba dam's reservoir formed the Basilwizi Trust in 2002. The Trust seeks mainly to improve the lives of people in the area through organizing development projects and serving as a conduit between the people of the Zambezi Valley and their country's decision-making process. [24]

River ecology

[edit]The Kariba Dam controls 90% of the total runoff of the Zambezi River, thus changing the downstream ecology dramatically.[25]

Wildlife rescue

[edit]From 1958 to 1961, Operation Noah captured and removed around 6,000 large animals and numerous small ones threatened by the lake's rising waters.[26]

Recent activity

[edit]On 6 February 2008, the BBC reported that heavy rain could lead to a release of water from the dam, which would force 50,000 people downstream to evacuate.[27] Rising levels led to the opening of the floodgates in March 2010, requiring the evacuation of 130,000 people who lived in the floodplain, and causing concerns that flooding would spread to nearby areas.[28]

In March 2014, at a conference organized by the Zambezi River Authority, engineers warned that the foundations of the dam had weakened and there was a possibility of dam failure unless repairs were made.[29]

On 3 October 2014 the BBC reported that "The Kariba Dam is in a dangerous state. Opened in 1959, it was built on a seemingly solid bed of basalt. But, in the past 50 years, the torrents from the spillway have eroded that bedrock, carving a vast crater that has undercut the dam's foundations. … engineers are now warning that without urgent repairs, the whole dam will collapse. If that happened, a tsunami-like wall of water would rip through the Zambezi valley, reaching the Mozambique border within eight hours. The torrent would overwhelm Mozambique's Cahora Bassa Dam and knock out 40% of southern Africa's hydroelectric capacity. Along with the devastation of wildlife in the valley, the Zambezi River Authority estimates that the lives of 3.5 million people are at risk."[30]

In June 2015 The Institute of Risk Management South Africa completed a Risk Research Report entitled Impact of the failure of the Kariba Dam. It concluded: "Whilst we can debate whether the Kariba Dam will fail, why it might occur and when, there is no doubt that the impact across the region would be devastating."[31]

In January 2016 it was reported that water levels at the dam had dropped to 12% of capacity. Levels fell by 5.58 metres (18.3 ft), which is just 1.75 metres (5 ft 9 in) above the minimum operating level for hydropower. Low rainfalls and overuse of the water by the power plants have left the reservoir near empty, raising the prospect that both Zimbabwe and Zambia will face water shortages.[32]

In July and September 2018, The Lusaka Times reported that work had started relating to the plunge pool and cracks in the dam wall.[33][34]

On 22 February 2019 Bloomberg reported "Zambia has reduced hydropower production at the Kariba Dam because of rapidly declining water levels" but "Zambia doesn't anticipate power cuts as a result of shortages".[35] On 5 August that year, the same publication reported that the reservoir was near empty, and that it may have to stop hydropower production.[36]

As of November 2020 the water level in the Kariba reservoir has remained steady around the 25% capacity, up from nearly half that in November 2019.[37] The Zambezi River Authority has stated that it is optimistic about rainfall estimates for the 2020/2021 rainfall season, allocating an increased amount of water for power production. At that time, the reservoir held 15.77 billion cubic meters of water, with the water line sitting at around 478.30 metres (1,569.23 ft), just above the minimum capacity for power generation of 475.50 metres (1,560.04 ft).[38]

It was reported in February 2022 that rehabilitation work has been underway since 2017 on the Kariba dam. The Zambezi River Authority (ZRA) said that work on the Kariba Dam Rehabilitation Project (KDRP), which includes efforts to reconfigure the plunge pool and rebuild the spillway gates, is scheduled to be finished in 2025. The rehabilitation of the dam is being financed by the European Union (EU), the World Bank, the Swedish government and the African Development Bank (AfDB), with the Zambian and Zimbabwe governments contributing counterpart funding. The project’s goal is to guarantee the structural integrity of the Kariba Dam, assuring the sustained generation of power primarily for the benefit of the inhabitants of Zimbabwe and Zambia and the broader Southern African Development Community area. The work on redesigning the plunge pool involves bulk excavating the rock in the current pool to assist plunge pool stabilization and avoid additional scouring or erosion along the weak fault zone towards the dam foundation. This reshaping work will be accomplished by constructing a temporary water-tight cofferdam to complete the reshaping work under dry conditions.[39]

An energy crisis due to drought and low water levels continued into January 2023, with water level falling to just 1% of capacity and output limited to 800 MW for a fraction of the day.[40][41]

Industrial power users have proposed a 250 MW floating solar plant on Lake Kariba to improve electricity reliability.[42]

See also

[edit]- Cahora Bassa Dam

- Nyami Nyami

- List of largest power stations in the world

- List of crossings of the Zambezi River

References

[edit]- ^ "Kariba Dam". Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Ed. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b Spurwing facts Archived November 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Indictment: Power & Politics in the Construction Industry, David Morrell, Faber & Faber, 1987, ISBN 978-0-571-14985-8

- ^ "Hydroelectric Power Plants in Southern Africa". Power Plants Around the World Photo Gallery. Industry Cards. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "Opening of Kariba Dam by HM The Queen Mother, May 1960". National Archives. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "PHmuseum: The Double Spiritual Nature of Lake Kariba". 19 July 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "Kariba Dam, Zambia and Zimbabwe; Final Report: November 2000" (PDF). World Commission on Dams. 2000. p. VI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ "Hydroelectric Power Plants in Southern Africa". IndustCards. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ 'No talks with the West' - Zimbabwe Archived 2013-12-15 at the Wayback Machine Zimbabwe Mail,10 May 2013

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Kariba South Power Expansion On Course". The Herald. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (30 March 2018). "Zimbabwe Commissions Chinese-Built Power Plant". Beijing: Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "DBSA provides $105m for Zambia hydropower expansion". Cramer Media's Engineering News. 5 November 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ "President Michael Sata commissions the Kariba North Bank extension hydro power station". Lusaka Times. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Zambia, Kariba Hydropower Plant, North bank extension". SinoHydro. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Kariba Dam, Zambia and Zimbabwe; Final Report: November 2000" (PDF). World Commission on Dams. 2000. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ "Agreement relating to the Central African power corporation signed at Salisbury". 25 November 1963. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Kariba Dam water levels will soon improve, says Zambezi River Authority". Lusaka Times. 17 February 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Legal Status". Zambezi River Authority. Archived from the original on 2010-04-06. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ^ Zesco: "History of Itezhi-Tezhi" Archived 2005-09-07 at the Wayback Machine website accessed 1 March 2007.

- ^ Terminski, Bogumil (2013). "Development-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: Theoretical Frameworks and Current Challenges". Indiana University.

- ^ Howarth, David, The Shadow of the Dam. Collins, 1961

- ^ "Pipe Dreams: Can the Zambezi River supply the region's water needs?". Cultural Survival Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "When Elephants Fight". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Basilwizi Trust: About Us". www.basilwizi.org. Basilwizi. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- ^ "The Zambezi Valley: damned by dams" (PDF). Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Operation Noah". Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Flood gates to open in Mozambique". February 6, 2008 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Zambia opens dam to alleviate flooding". March 15, 2010 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ IRIN (9 April 2014). "Kariba Dam and Zim disaster preparedness". New Zimbabwe. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "The marooned baboon: Africa's loneliest monkey". BBC. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Impact of the failure of the Kariba Dam" (PDF). International Rivers. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ "Kariba dam drops to record low 12%, and Zimbabwe, Zambia stare at a nightmare". Mail & Guardian Africa. 2016-01-20. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ^ "Kariba dam rehabilitation works are progressing well". Lusakatimes.com. 19 July 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ "Initial rehabilitation works on the Dam Wall at Lake Kariba has started". Lusakatimes.com. 5 September 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ "Zambia Cuts Power From World's Biggest Man-Made Reservoir". Bloomberg.com. 22 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Hill, Matthew; Ndlovu, Ray (5 August 2019). "Power-Starved Zimbabwe, Zambia Face Further Drought-Induced Blackouts". Bloomberg. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "Kariba Reservoir Data | Zambezi River Authority". www.zambezira.org. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ^ "ZRA allots more water for Kariba generation". Zimbabwe Situation. 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ Otieno, Patrick (May 13, 2014). "Kariba Dam Rehabilitation Project (KDRP) Updates". Construction Review Online.

- ^ Ajasa, Amudalat (January 4, 2023). "Low water levels have created an energy crisis at the world's largest dam". Washington Post.

- ^ "Power crisis looms in Zambia as world's largest man-made dam dries up". LifeGate. 2023-01-25. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ^ "Zimbabwe Industrial Power Users Aim to Raise $250 Million for Floating Solar Panels - BNN Bloomberg". BNN. 2023-07-05. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

External links

[edit]- Dams in Zambia

- Dams in Zimbabwe

- Lake Kariba

- Zambezi River

- Arch dams

- Buildings and structures in Mashonaland West Province

- Dams completed in 1959

- 1959 establishments in Northern Rhodesia

- 1959 establishments in Southern Rhodesia

- 1959 establishments in Africa

- Tourist attractions in Zambia

- Tourist attractions in Zimbabwe

- Rhodesia–Zambia relations

- Zambia–Zimbabwe border