History of the Kalenjin people

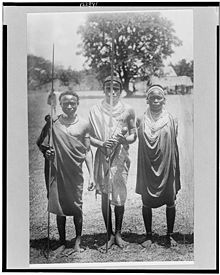

The Kalenjin people are an ethnolinguistic group indigenous to East Africa, with a presence, as dated by archaeology and linguistics, that goes back many centuries. Their history is therefore deeply interwoven with those of their neighboring communities as well as with the histories of Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, and Ethiopia.

Origins

[edit]Genetic studies of Nilo-Saharan-speaking populations are in general agreement with archaeological evidence and linguistic studies that argue for a Nilo-Saharan homeland in eastern Sudan before 6000 BCE, with subsequent migration events northward to the eastern Sahara, westward to the Chad Basin, and southeastward into Kenya and Tanzania.[1]

Linguist Roger Blench has suggested that the Nilo-Saharan languages and the Niger–Congo languages may be branches of the same macro–language family.[2][3] Earlier proposals along this line were made by linguist Edgar Gregersen in 1972.[4] These proposals have not reached a linguistic consensus, however, and this connection presupposes that all of the Nilo-Saharan languages are actually related in a single family, which has not been definitively established.

Linguist Christopher Ehret has made a case that a proto-Nilotic language was spoken by the third millennium B.C.[5] He cites the eastern Middle Nile Basin south of the Abbai River as the supposed urheimat of the speakers of this language, that is to say south-east of present-day Khartoum.[6]

Beginning in the second millennium B.C., particular Nilotic communities began to move southward into far South Sudan, where most settled. However, the societies today referred to as the Southern Nilotes pushed further on, reaching what is present-day north-eastern Uganda by 1000 B.C.[6]

The earliest area in the Great Lakes region that is recognized as inhabited by the Southern Nilotic speakers lies in the present day Jie and Dodoth country in Uganda.[7]

Early presence in East Africa

[edit]

Ehret postulates that between 1000 and 700 BC, the Southern Nilotic speaking communities, who kept domestic stock and possibly cultivated sorghum and finger millet, lived next to an Eastern Cushitic speaking community with whom they had significant cultural interaction. The general location of this point of cultural exchange was somewhere near the common border between Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia.

This corresponds with a number of historical narratives from the various Kalenjin sub-tribes, which point to Tulwetab/Tuluop Kony (Mount Elgon) as their original point of settlement in Kenya.

There are also accounts from Kalenjin speaking communities, in particular, the Sebeii, living near Mt. Elgon, who point to Kong'asis (the East), and more specifically the Cherangani Hills, as their original homelands in Kenya.[8]

The impact of the cultural exchange that occurred around the Mt. Elgon region was most notable in borrowed loan words, adoption of the practice of circumcision, and the cyclical system of age-set organisation.[9]

Neolithic

[edit]

The arrival of the Southern Nilotes on the East African archaeological scene is correlated with the appearance of the prehistoric lithic industry and pottery tradition referred to as the Elmenteitan culture.[10] The bearers of the Elmenteitan culture developed a distinct pattern of land use, hunting, and pastoralism on the western plains of Kenya during the East African Pastoral Neolithic. Its earliest recorded appearance dates to the ninth century BC (i.e. 900 to 801 BC).[11]

It is thought that around the fifth and sixth centuries BC, the speakers of the Southern Nilotic languages split into two major divisions: the proto-Kalenjin and the proto-Datooga. The former took shape among those residing to the north of the Mau range, while the latter took shape among sections that moved into the Mara and Loita plains south of the western highlands.[12]

While few large-scale excavations have been done on sites outside the Central Rift, regional surveys indicate that the population was far denser in the southern highlands during this time.[13]

The Datooga were specialized pastoralists on considerable scale, spreading their settlements westward after 400BC across the Mara plains and as far as southeastern Lake Nyanza. Their presence on the Mara and Loita plains would continue through to the seventeenth century AD when they were driven south by the Maasai during the Il-Tatua wars.[14]

Archaeological and linguistic evidence point to significant differences in ways of life between the Elmenteitan culture and the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic cultures that had preceded them in Kenya.

Lithic industry

[edit]

For both the Elmenteitan and SPN producing societies, obsidian was the dominant source of lithic raw material for tool production, though lower quality alternatives were used occasionally. The obsidian was sourced at two discrete points with the Elmenteitan culture sourcing their obsidian from an outcrop of green obsidian on the northeast slope of Mt. Eburu.[15]

Social organisation

[edit]The Southern Nilotes of this time, like some of their neighbors, practiced circumcision of both sexes though significant differences in practice are discerned through linguistics. Unlike the Southern Cushities and somewhat like the early Bantu, they initiated circumcised men into age-sets. The age-sets, however, were quite different from those of the Bantu of the time in that they formed a cycling system which in its early form comprised both age-sets as well as a generational component. It is thought that the eight age-sets in the system were grouped into two generations, each comprising four of the sets. Within the system, a man and his son would belong to age-sets that were of alternate generations.

Alongside the age-sets there was an age grade system which had been simplified to a two-tier system by the early stages of the Sirikwa era. By that time, a young man when initiated would join an age-set while simultaneously joining the first age-grade known as muren. At the same time, his father would join the senior age-grade known as payyan. It is speculated, though yet unproven, that the age-grade system of the Southern Nilotic period comprised four pairs of age-grades to match the four stages of each generation in the age-set system. The full complexity of this system would breakdown differently in the descendant communities with the Kalenjin retaining the age-sets and losing the age-grades while the Datooga dropped the age-sets and retained the age-grades as central to social cohesion.[14]

Burials

[edit]The Southern Nilotic speakers cremated their deceased in caves as at Njoro River cave, Keringet caves and possibly Egerton caves, much unlike the Southern Cushitic speakers who buried their dead in cairns. Both however had similar grave goods, which typically included stone bowls, pestle rubbers and palettes.[16][17]

Pastoral iron age

[edit]Early iron age

[edit]Linguistic studies indicate separate and significant interaction between the Southern Nilotic speakers and Bantu speaking communities. Word evidence shows that in this interaction, there was highly gendered migration from the Bantu speaking communities into Southern Nilotic-speaking areas during the period, ca. 500-800 A.D., with Luhya women being the migrants.

The evidence for this lies in the words that passed from the Bantu language into the Southern Nilotic language during this period. In contrast to the wide variety of Kalenjin loanwords in Luhya today, all but one of the words that were adopted from Luhya relate to cultivation and cooking, which were traditionally women's duties in ancient Luhya society.

It has been suggested that the social institution of marriage led to the select migration. In that, whereas the Southern Nilotic speaking pastoralists contracted marriage through payment of cattle and other livestock by the groom's family to the prospective bride's family, the Bantu of 1500 to 2000 years ago likely contracted marriage through bride service, whereby the prospective groom would work in the potential bride's household for a period of time. This arrangement, therefore, served to make men the migrants in contrast to payment of bride price which made women the migrants.

The marrying of Luhya women to Kalenjin men would have conferred benefits to men of both societies at the time since for the Kalenjin, Luhya women would have contributed expanded agricultural variety and productivity to the homestead. On the other hand, a Luhya father, by marrying his daughter to a Kalenjin man could increase his own wealth and position within Luhya society. Over the long term such relations, by increasing men's wealth in cattle, undoubtedly helped bring into being new customary balance's between men and women's authority and status in Luhya society. These societies are today patrilineal unlike the ancient Luhya societies which appear to have been matrilineal.[18]

Late iron age

[edit]From the archaeological record, it is postulated that the emergence and early development of the Sirikwa culture occurred in the central Rift Valley i.e. Rongai/Hyrax Hill, not later than the 12th century A.D.[19] Between this period and about the 17th century i.e prior to the Loikop expansion -the Sirikwa pioneered an advanced form of pastoral management. They were not the first culture to herd cattle, goats and sheep in the high grasslands; this having happened at least two thousand years previously. The achievement of the Sirikwa culture, sometime after 1000AD, was the introduction of a more efficient exploitation of the lush pastures through less emphasis on beef and more on dairy production. For this purpose they perfected a small breed of Zebu cattle - what is essentially now known as the Maasai breed - whose milk yield though modest in volume is rich in quality. With herds of sufficient size and mobility, combined with sheep and goat for a regular meat supply, the bearers of the Sirikwa culture pioneered an efficient way of exploiting unenclosed tracts of high grassland.[20] This innovation likely allowed for the expansion, as attested archaeologically, from the central Rift Valley into the western highlands, the Mt. Elgon region and possibly into Uganda.[19]

For several centuries, the bearers of the Sirikwa culture would be the dominant population of the western highlands of Kenya. At their greatest extent, their territories covered the highlands from the Chepalungu and Mau forests northwards as far as the Cherangany Hills and Mount Elgon. There was also a south-eastern projection, at least in the early period, into the elevated Rift grasslands of Nakuru which was taken over permanently by the Maasai, probably no later than the seventeenth century. Here Kalenjin place names seem to have been superseded in the main by Maasai names[21] notably Mount Suswa (Kalenjin - place of grass) which was in the process of acquiring its Maasai name, Ol-doinyo Nanyokie, the red mountain during the period of European exploration.[22]

Archaeological evidence indicates a highly sedentary way of life and a cultural commitment to a closed defensive system for both the community and their livestock during the Sirikwa period. Family homesteads featured small individual family stock pens, elaborate gate-works and sentry points and houses facing into the homestead; defensive methods primarily designed to proof against individual thieves or small groups of rustlers hoping to succeed by stealth.[23] Links with external trade networks are indicated by caravan routes from the Swahili coast that led to, or cut through the territories of the bearers of the Sirikwa culture.[24]

Pre-19th century

[edit]A body of oral traditions from various East African communities points to the presence of at least four significant Kalenjin-speaking population groups present prior to the 19th century. Meru oral history describes the arrival of their ancestors at Mount Kenya where they interacted with a community referred to as Lumbwa. The Lumbwa occupied the lower reaches of Mount Kenya though the extent of their territory is presently unclear.[25] North-east of this community, across the Rift Valley, a community known as the Chok (later Suk) occupied the Elgeyo escarpment. Pokot oral history describes their way of life, as that of the Siger (or Sengwer), a community that appears to have lived in association with the Chok. The name Siger was used by the Karamojong and arose from a distinctive cowrie shell adornment favored by this community. The area occupied by the Sekker stretched between Mount Elgon and present-day Uasin Gishu as well as into a number of surrounding counties.[26] Far west, a community known as the Maliri occupied present day Jie and Dodoth country in Uganda. The Karamojong would eject them from this region over the course of the century and their traditions describe these encounters with the Maliri. The arrival in the district of the latter community is thought by some to be in the region of six to eight centuries ago.[27]

Bordering these communities were two distinct communities whose interactions and those with the Kalenjin-speaking communities would lead to notable cultural change. The Maliri in Uganda were neighbored by the Karamojong, an Iron Age community that practiced a pastoral way of life.[28] To the north of the Sekker and Chok were the Oropom (Orupoi), a late neolithic society whose expansive territory is said to have stretched across Turkana and the surrounding region as well as into Uganda and Sudan. Wilson (1970) who collected traditions relating to the Oropom observed that the corpus of oral literature suggested that, at its tail end, the society "had become effete, after enjoying for a long period the fruits of a highly developed culture".[29]

Towards the end of 18th century and through the 19th century, a series of droughts, plagues of locusts, epidemics, and in the final decades of the 19th century, a rapid succession of sub-continental epizootics affected these communities. There is an early record of the great Laparanat drought c.1785 that affected the Karamajong.[30] However, for communities then resident in what is present-day Kenya many disaster narratives relate the start with the Aoyate, an acute meteorological drought that affected much of East and Southern Africa in the early nineteenth century.

19th century

[edit]Nile records indicate that the three decades starting about 1800 were marked by low rainfall levels in regions south of the Sahara. East African oral narratives and the few written records indicate peak aridity during the 1830s resulting in recorded instances of famine in 1829 and 1835 in Ethiopia and 1836 in Kenya. Among Kenyan Rift Valley communities this arid period, and the consequent series of events, have been referred to as Mutai.[31]

A feature of the Mutai was increased conflict between neighboring communities, most noted of these has been the Iloikop wars. Earlier conflicts preceding the Iloikop wars appear to have brought about the pressures that resulted in this period of conflict. Von Höhnel (1894) and Lamphear (1988) recorded narratives concerning conflict between the Turkana and Burkineji or at least the section recalled as Sampur that appear to have been caused by even earlier demographic pressures.

Turkana - Burkineji conflict

[edit]

Turkana narratives recorded by Lamphear (1988) provide a broad perspective of the prelude to the conflict between the Turkana and a community he refers to as Kor, a name by which the Turkana still call the Samburu in the present day.

By the end of the Palajam initiations, the developing Turkana community was experiencing strong ecological pressures. Behind them, up the escarpment in Karamoja, other evolvig Ateker societies such as the Karimojong and Dodos were occupying all available grazing lands. Therefore Turkana cattle camps began to push further down the Tarash, which ran northwards below the foothills of the Moru Assiger massif on their right and the escarpment on their left. As they advanced, the Turkana came to realize they were not alone in this new land. At night fires could be seen flickering on the slopes of nearby mountains, including Mt. Pelekee which loomed up in the distance directly before them...

— John Lamphear, 1988[32]

Lamphear notes that Tukana traditions aver that a dreamer among them saw strange animals living with the people up in the hills. Turkana warriors were thus sent forward to capture one of these strange beasts, which the dreamer said looked 'like giraffes, but with humps on their backs'. The young men therefore went and captured one of these beasts - the first camels the Turkana had seen. The owners of the strange beasts appear to have struck the Turkana as strange as well. The Turkana saw them as 'red' people, partly because of their lighter skin and partly because they daubed their hair and bodies with reddish clay. They thus gave them the name 'Kor'. Lamphear states that Turkana traditions agree that the Kor were very numerous and lived in close pastoral association with two other communities known as 'Rantalle' and 'Poran', the names given to the Cushitic speaking Rendille and Boran communities.[32]

According to Von Höhnel (1894) "a few decades" prior, the Burkineji occupied districts on the west of the lake and that they were later driven eastwards into present day Samburu. He later states that "some fifty years ago the Turkana owned part of the land on the west now occupied by the Karamoyo, whilst the southern portion of their land belonged to the Burkineji. The Karamoyo drove the Turkana further east, and the Turkana, in their turn, pushed the Burkineji towards Samburuland".[33]

Collapse of Siger community

[edit]Lamphear states that Turkana narratives indicate that at the time of interaction with the 'Kor', the Turkana were in even closer proximity to a community referred to as Siger. This was the Karamoja name for the community and derived from an adornment that this community favored. The Siger like the Kor, were seen as a 'red' people, they are also remembered as a 'heterogeneous, multi-lingual confederation, including Southern and Eastern Nilotic-speakers, and those who spoke Cushitic dilects'. According to Turkana traditions the Siger once held most of the surrounding country 'until the Kor and their allies came up from the south and took it from them. In the process, the Kor and Siger had blended to some extent'.[32]

According to Lamphears account, Turkana traditions directly relate the collapse of the 'Siger' to the Aoyate. He notes that;

...as Turkana cattle camps began making contact with these alien populations and their strange livestock, the area was beset by a terrible drought, the Aoyate, 'the long dry time'...The Siger community was decimated and began to collapse. Some abandoned their mountain and fled eastwards, but ran into even drier conditions: '[It] became dry and there was great hunger. The Siger went away to the east to Moru Eris, where most of them died of heat and starvation. So many died that there is still a place called Kabosan ["the rotten place"]'. Bands of Turkana fighting men forced the Siger northwards to the head of Lake Turkana...Still others were pushed back onto the Suk Hills to the south to be incorporated by the Southern-Nilotic speaking Pokot...Many were assimilated by the Turkana...and the victors took possession of the grazing and water resources of Moru Assiger

— As narrated to J. Lamphear, 1988[34]

The collapse of the Siger/Sengwer community is generally believed to have seen the rise of a prophet-diviner class among many pastoral communities and a period marked by reformation.

Cultural changes, particularly the innovation of heavier and deadlier spears amongst the Loikop led to significant changes in methods and scale of raiding. The change in methods introduced by the Loikop also consisted of fundamental differences of strategy, in fighting and defense, and also in organization of settlements and of political life.[23]

The cultural changes played a part in significant southward expansion of Loikop territory from a base east of Lake Turkana. This expansion led to the development of three groupings within Loikop society. The Sambur who occupied the 'original' country east of Lake Turkana as well as the Laikipia plateau. The Uasin Gishu occupied the grass plateaus now known as the Uasin Gishu and Mau while the Maasai territory extended from Naivasha to Kilimanjaro.[35] This expansion was subsequently followed by the Iloikop wars.[36]

The expansion of Turkana and Loikop societies led to significant change within the Sirikwa society. Some communities were annihilated by the combined effects of the Mutai of the 19th century while others adapted to the new era.

Iloikop wars

[edit]Members of collapsing communities were usually assimilated into ascending identities.

Significant cultural change also occurred. Guarding cattle on the plateaus depended less on elaborate defenses and more on mobility and cooperation. Both of these requiring new grazing and herd-management strategies. The practice of the later Kalenjin – that is, after they had abandoned the Sirikwa pattern and had ceased in effect to be Sirikwa – illustrates this change vividly. On their reduced pastures, notably on the borders of the Uasin Gishu plateau, when bodies of raiders approached they would relay the alarm from ridge to ridge, so that the herds could be combined and rushed to the cover of the forests. There, the approaches to the glades would be defended by concealed archers, and the advantage would be turned against the spears of the plains warriors.[37]

More than any of the other sections, the Nandi and Kipsigis, in response to Maasai expansion, borrowed from the Maasai some of the traits that would distinguish them from other Kalenjin: large-scale economic dependence on herding, military organization and aggressive cattle raiding, as well as centralized religious-political leadership. The family that established the office of Orkoiyot (warlord/diviner) among both the Nandi and Kipsigis were migrants from northern Chemwal regions. By the mid-nineteenth century, both the Nandi and Kipsigis were expanding at the expense of the Maasai.[38]

The Iloikop wars ended in the 1870s with the defeat and dispersal of the Laikipiak. However, the new territory acquired by the Maasai was vast and left them overextended thus unable to occupy it effectively.[39] This left them open to encroachment by other communities. By the early 1880s, Kamba, Kikuyu and acculturating Sirikwa/Kalenjin raiders were making inroads into Maasai territory, and the Maasai were struggling to control their resources of cattle and grazing land.[40]

The latter decades of the nineteenth century, saw the early European explorers start advancing into the interior of Kenya. Many present-day identities were by then recognized and begin to appear in the written record. In the introduction to Beech's account on the Suk, Eliot notes that they seemed "unanimous in tracing their origin to two tribes called Chôk(or Chũk) and Sekker (and that) at present they call themselves Pôkwut...', he also recognizes five dialects, "Nandi, Kamasia, Endo (and) Suk, the difference being the greatest between the first and the last. The Maragwet language, which is presumably akin, appears not to have been studied, and there are probably others in the same case".

About the time contacts were being made this time, two instances of epizootics broke out in the Rift Valley region. In 1883, bovine Pleuro-Pneumonia spread from the north and lingered for several years. The effect of this was to cause the Loikop to regroup and to go out raiding more aggressively to replenish their herds. This was followed by a far more serious outbreak of Rinderpest which occurred in 1891.[41]

This period - characterized by disasters, including a rinderpest epidemic, other stock diseases, drought, mass starvation, and smallpox was referred to as a Mutai.

20th century

[edit]Resistance to British rule

[edit]By the latter decades of the nineteenth century, the Kalenjin - more so the Nandi, had acquired a fearsome reputation. Thompson was warned in 1883 to avoid the country of the Nandi, who were known for attacks on strangers and caravans that would attempt to scale the great massif of the Mau.[42]

Nonetheless, trade relations were established between the Kalenjin and incoming British. This was tempered on the Kalenjin side by the prophesies of various seers. Among the Nandi, Kimnyole had warned that contact with the Europeans would have a significant impact on the Nandi while Mongo was said to have warned against fighting the Europeans.

Matson, in his account of the resistance, shows 'how the irresponsible actions of two British traders, Dick and West, quickly upset the precarious modus vivendi between the Nandi and incoming British'.[43] Conflict, led on the Nandi side by Koitalel Arap Samoei - Nandi Orkoiyot at the time, was triggered by West's killing in 1895.

The East Africa Protectorate, Foreign Office, and missionary societies administrations reacted to West's death by organizing invasions of Nandi in 1895 and 1897.[44] Invading forces were able to inflict sporadic losses upon Nandi warriors, steal hundreds of livestock, and burn villages, but were not able to end Nandi resistance.[44]

1897 also saw the colonial government set up base in Eldama Ravine under the leadership of certain Messrs. Ternan and Grant, an intrusion that was not taken to kindly by the Lembus community. This triggered conflict between the Lembus and the British, the latter of whom fielded Maasai and Nubian soldiers and porters.

The British eventually overcame the Lembus following which Grant and Lembus elder's negotiated a peace agreement. During the negotiations, the Lembus were prevailed upon by Grant to state what they would not harm nor kill, to which the response was women. As such, they exchanged a girl from the Kimeito clan while Grant offered a white bull as a gesture of peace and friendship. This agreement was known as the Kerkwony Agreement. The negotiations were held where Kerkwony Stadium stands today.[45]

On October 19, 1905, on the grounds of what is now Nandi Bears Club, Arap Samoei was asked to meet Col Richard Meinertzhagen for a truce. A grand-nephew of one of Arap Samoei's bodyguards later noted that “There were about 22 of them who went for a meeting with the (European) that day. Koitalel Arap Samoei had been advised not to shake hands because if he did, that would give him away as the leader. But he extended his hand and was shot immediately".[46] Koitalel's death led to the end of the Nandi resistance.

Kalenjin identity

[edit]Until the mid-20th century, the Kalenjin did not have a common name and were usually referred to as the 'Nandi-speaking tribes' by scholars and colonial administration officials.

Starting in the 1940s, individuals from the various 'Nandi-speaking tribes' who had been drafted to fight in World War II (1939–1945) began using the term Kale or Kore (a term that denoted scarification of a warrior who had killed an enemy in battle) to refer to themselves. At about the same time, a popular local radio broadcaster by the name of John Chemallan would introduce his wartime broadcasts show with the phrase Kalenjok meaning "I tell You" (when said to many people). This would influence a group of fourteen young 'Nandi-speaking' men attending Alliance School and who were trying to find a name for their peer group. They would call it Kalenjin meaning "I tell you" (when said to one person). The word Kalenjin was gaining currency as a term to denote all the 'Nandi-speaking' tribes. This identity would be consolidated with the founding of the Kalenjin Union in Eldoret in 1948 and the publication of a monthly magazine called Kalenjin in the 1950s.

In 1955 when Mzee Tameno, a Maasai and member of the Legislative Assembly (LEGCO) for Rift Valley, tendered his resignation, the Kalenjin presented one candidate to replace him; Daniel Toroitich arap Moi.

By 1960, concerned with the dominance of the Luo and Kikuyu, Arap Moi and Ronald Ngala formed KADU to defend the interests of the countries smaller tribes. They campaigned on a platform of majimboism (devolution) during the 1963 elections but lost to KANU. Shortly after independence in December 1963, Kenyatta convinced Moi to dissolve KADU. This was done in 1964 when KADU dissolved and joined KANU.

21st century

[edit]

The Kalenjin have been called by some "the running tribe." Since the mid-1960s, Kenyan men have earned the largest share of major honours in international athletics at distances from 800 meters to the marathon; the vast majority of these Kenyan running stars have been Kalenjin.[47] From 1980 on, about 40% of the top honours available to men in international athletics at these distances (Olympic medals, World Championships medals, and World Cross Country Championships honours) have been earned by Kalenjin.

In 2008, Pamela Jelimo became the first Kenyan woman to win a gold medal at the Olympics; she also became the first Kenyan to win the Golden League jackpot in the same year.[48] Since then, Kenyan women have become a major presence in international athletics at the distances; most of these women are Kalenjin.[47] Amby Burfoot of Runner's World stated that the odds of Kenya achieving the success they did at the 1988 Olympics were below 1:160 billion. Kenya had an even more successful Olympics in 2008.

A number of theories explaining the unusual athletic prowess among people from the tribe have been proposed. These include many explanations that apply equally well to other Kenyans or people living elsewhere who are not disproportionately successful athletes, such as that they run to school every day, that they live at relatively high altitude, and that the prize money from races is large compared to typical yearly earnings. One theory is that the Kalenjin has relatively thin legs and therefore does not have to lift so much leg weight when running long distances.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ Michael C. Campbell and Sarah A. Tishkoff, "The Evolution of Human Genetic and Phenotypic Variation in Africa," Current Biology, Volume 20, Issue 4, R166–R173, 23 February 2010

- ^ Blench, Roger. KORDOFANIAN and Niger–Congo: NEW AND REVISED LEXICAL EVIDENCE" (Draft) (PDF).

- ^ Blench, R.M. 1995, 'Is Niger–Congo simply a branch of Nilo-Saharan?' In: Proceedings of the Fifth Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium, Nice, 1992. ed. R. Nicolai and F. Rottland. 68–118. Köln: Rudiger Köppe.

- ^ Gregersen, Edgar A (1972). "Kongo-Saharan". Journal of African Linguistics. 4: 46–56.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (1974). "Some Thoughts on the Early History of the Nile-Congo Watershed" (PDF). Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies. 5/2: 90.

- ^ a b Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p. 7

- ^ De Vries, Kim. Identity Strategies of the Argo-pastoral Pokot: Analyzing ethnicity and clanship within a spatial framework. Universiteit Van Amsterdam, 2007 p. 39

- ^ Kipkorir, B.E. The Marakwet of Kenya: A preliminary study. East Africa Educational Publishers Ltd, 1973, p. 64

- ^ Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p.161-164

- ^ Ehret, C., History and the Testimony of Language, p.118 online

- ^ Lane, Paul J. (2013-07-04). Mitchell, Peter; Lane, Paul J. (eds.). "The Archaeology of Pastoralism and Stock-Keeping in East Africa". doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199569885.001.0001. ISBN 9780199569885.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ehret, C., History and the Testimony of Language, p.118

- ^ Goldstein, S., Quantifying endscraper reduction in the context of obsidian exchange among early pastoralists in southwestern Kenya, 2014, W.S.Mney & Son, p.5 online

- ^ a b Ehret, C., An African Classical Age, Eastern & Southern Africa in World History, 1000B.C to A.D400, p.162

- ^ Goldstein, S., Quantifying endscraper reduction in the context of obsidian exchange among early pastoralists in southwestern Kenya, 2014, W.S.Mney & Son, p.5

- ^ Robertshaw, P., The Elmenteitan; an early food producing culture in East Africa, Taylor & Francis, p.57 online

- ^ Ehret, C., and Posnansky M., The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History, University of California, 1982 online

- ^ Lacassen, J. Lacassen, L. and Manning, P, Migration History in World History: Multidisciplinary Approaches, 2010 pg. 139

- ^ a b Kyule, David M., 1989, Economy and subsistence of iron age Sirikwa Culture at Hyrax Hill, Nakuru: a zooarcheaological approach p. 211

- ^ Sutton, John (1994). "The Sirikwa and the Okiek in the history of the Kenya highlands". Kenya Past and Present (26): 35–36. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 42 (online)

- ^ Pavitt, N. Kenya: The First Explorers, Aurum Press, 1989, p. 107

- ^ a b Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 44-46 (online)

- ^ Hollis A.C, The Nandi - Their Language and Folklore. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1909, p. xvii

- ^ Fadiman, J. (1994). When We Began There Were Witchmen. California: University of California Press. pp. 83–89. ISBN 9780520086159.

- ^ Beech, M.W.H (1911). The Suk - Their Language and Folklore. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 2.

- ^ Wilson, J.G. (1970). "Preliminary Observation On The Oropom People Of Karamoja, Their Ethnic Status, Culture And Postulated Relation To The Peoples Of The Late Stone Age". The Journal of the Uganda Society. 34 (2): 130. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, J.G. (1970). "Preliminary Observation On The Oropom People Of Karamoja, Their Ethnic Status, Culture And Postulated Relation To The Peoples Of The Late Stone Age". The Journal of the Uganda Society. 34 (2): 133.

- ^ Wilson, J.G. (1970). "Preliminary Observation On The Oropom People Of Karamoja, Their Ethnic Status, Culture And Postulated Relation To The Peoples Of The Late Stone Age". The Journal of the Uganda Society. 34 (2): 131.

- ^ Weatherby, John (2012). The Sor Or Tepes of Karamoja (Uganda): Aspects of Their History and Culture. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. p. 47. ISBN 9788490120675.

- ^ Fukui, Katsuyoshi; Markakis, John (1994). Ethnicity & Conflict in the Horn of Africa. Oxford: James Currey Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 9780852552254.

- ^ a b c Lamphear, John (1988). "The People of the Grey Bull: The Origin and Expansion of the Turkana". The Journal of African History. 29 (1): 30. doi:10.1017/S0021853700035970. JSTOR 182237. S2CID 162844531.

- ^ Höhnel, Ritter von (1894). Discovery of lakes Rudolf and Stefanie; a narrative of Count Samuel Teleki's exploring & hunting expedition in eastern equatorial Africa in 1887 & 1888. London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 234-237.

- ^ Lamphear, John (1988). "The People of the Grey Bull: The Origin and Expansion of the Turkana". The Journal of African History. 29 (1): 32–33. doi:10.1017/s0021853700035970. JSTOR 182237. S2CID 162844531.

- ^ MacDonald, J.R.L (1899). "Notes on the Ethnology of Tribes Met with During Progress of the Juba Expedition of 1897-99". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 29 (3/4): 240. doi:10.2307/2843005. JSTOR 2843005.

- ^ MacDonald, J.R.L (1899). "Notes on the Ethnology of Tribes Met with During Progress of the Juba Expedition of 1897-99". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 29 (3/4): 240. doi:10.2307/2843005. JSTOR 2843005.

- ^ Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 47 (online)

- ^ Nandi and Other Kalenjin Peoples – History and Cultural Relations, Countries and Their Cultures. Everyculture.com forum. Accessed 19 August 2014

- ^ Waller, Richard (1976). "The Maasai and the British 1895-1905. the Origins of an Alliance". The Journal of African History. 17 (4): 532. doi:10.1017/S002185370001505X. JSTOR 180738. S2CID 154867998.

- ^ Waller, Richard (1976). "The Maasai and the British 1895-1905. the Origins of an Alliance". The Journal of African History. 17 (4): 529–53. doi:10.1017/s002185370001505x. JSTOR 180738. S2CID 154867998.

- ^ Waller, Richard (1976). "The Maasai and the British 1895-1905. the Origins of an Alliance". The Journal of African History. 17 (4): 530. doi:10.1017/S002185370001505X. JSTOR 180738. S2CID 154867998.

- ^ Pavitt, N. Kenya: The First Explorers, Aurum Press, 1989, p. 121

- ^ Nandi Resistance to British Rule 1890–1906. By A. T. Matson. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972. Pp. vii+391

- ^ a b Bishop, D. Warriors in the Heart of Darkness: The Nandi Resistance 1850 to 1897, Prologue

- ^ Town Council of Eldama Ravine (August 26, 2006). Strategic Plan 2006-2012 (Report). Town Council of Eldama Ravine. p. 2. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ EastAfrican, December 5, 2008: Murder that shaped the future of Kenya

- ^ a b Why Kenyans Make Such Great Runners: A Story of Genes and Cultures, Atlantic online

- ^ Million Dollar Legs, The Guardian online

- ^ Running Circles around Us: East African Olympians’ Advantage May Be More Than Physical, Scientific American online