Kakheti

Kakheti

კახეთი | |

|---|---|

From the top to bottom-right: Lagodekhi Managed Reserve, Tusheti National Park, Vashlovani Strict Nature Reserve, Kakheti Vineyard, Tsinandali Palace | |

| |

| Coordinates: 41°45′N 45°43′E / 41.750°N 45.717°E | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Telavi |

| Municipalities | 8 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Giorgi Aladashvili |

| Area | |

• Total | 11,310 km2 (4,370 sq mi) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 310,051 |

• Estimate (2023)[1] | 306,216 |

| • Density | 27/km2 (71/sq mi) |

| Gross Regional Product | |

| • Total | ₾ 3.13 billion (2022) |

| • Per Capita | ₾ 10,235 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (Georgian Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | GE-KA |

| HDI (2021) | 0.757[3] high · 5th |

| Website | www |

Kakheti (Georgian: კახეთი K’akheti; [kʼaχetʰi]) is a region (mkhare) formed in the 1990s in eastern Georgia from the historical province of Kakheti and the small, mountainous province of Tusheti. Telavi is its administrative center. The region comprises eight administrative districts: Telavi, Gurjaani, Qvareli, Sagarejo, Dedoplistsqaro, Signagi, Lagodekhi and Akhmeta.

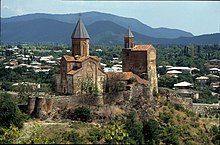

Kakhetians speak the Kakhetian dialect of Georgian. Kakheti is one of the most significant wine producing regions of Georgia, home to a number of Georgian wines. The region is bordered to the west by the Georgian regions of Mtskheta-Mtianeti and Kvemo Kartli, to the north and east by the Russian Federation, and to the southeast by Azerbaijan. Popular tourist attractions in Kakheti include Tusheti, Gremi, Signagi, Kvetera, Bodbe, Lagodekhi Protected Areas and Alaverdi Monastery.

The Georgian David Gareja monastery complex is partially located in this province and is subject to a border dispute between Georgian and Azerbaijani authorities.[4]

Geography

[edit]

Beyond the modern-day administrative subdivision into the districts, Kakheti has traditionally been subdivided into four parts: Inner Kakheti (შიდა კახეთი, Shida Kakheti) to the east of Tsiv-Gombori mountain range, along the right bank of the Alazani River; Outer Kakheti (გარე კახეთი, Gare Kakheti) along the middle Iori River basin; Kiziq'i (ქიზიყი) between the Alazani and the Iori; Thither Area (გაღმა მხარი, Gaghma Mkhari) on the left bank of the Alazani. It also includes the medieval region of Hereti whose name has fallen into gradual oblivion since the 15th century.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

The Kakheti region is divided into eight municipalities:[5]

| Name | Area | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Telavi Municipality | 1,094 km2 | 58,350 |

| Akhmeta Municipality | 2,248 km2 | 31,461 |

| Gurjaani Municipality | 849 km2 | 54,337 |

| Kvareli Municipality | 1,000 km2 | 29,827 |

| Dedoplistskaro Municipality | 2,531 km2 | 21,221 |

| Lagodekhi Municipality | 890 km2 | 41,678 |

| Sagarejo Municipality | 1,515 km2 | 51,761 |

| Sighnaghi Municipality | 1,251 km2 | 29,948 |

History

[edit]Kakheti was an independent principality from the end of the eighth century. It was incorporated into the united Georgian Kingdom at the beginning of the eleventh century, but for less than a decade. Only in the beginning of the twelfth century did Georgian King David the Builder (1089–1125) incorporate Kakheti into his Kingdom successfully.[citation needed]

Fifteenth–Sixteenth centuries: peace and prosperity, geopolitical situation

[edit]After the disintegration of the Georgian Kingdom, Kakheti became an independent Kingdom in the 1460s. In contrast with other Georgian political entities, long reign of Kakhetian Kings – Alexander I (1476-1511), Levan (1518-1574) and Alexander II (1574-1605), was marked by peace and prosperity, population grew steadily and at the turn of the seventeenth century reached 250,000–300,000. Gremi, capital city of the Kingdom and Zagemi became one of the most important urban centers of the Caucasus, attracting merchants and artisans from the neighbouring countries. New churches, castles and palaces were built and agriculture developed.

During the last years of the sixteenth century Kakhetian feudal army consisted of 10,000 cavalrymen, 3,000 infantry and 500 musketeers. Horsemen and foot soldiers were armed with bows, arrows, sabres, shields and spears, while musketeers had hand-guns.[6] Furthermore, Alexander II made some futile efforts to introduce artillery from Muscovy.

During the sixteenth century international situation of the Georgian Kingdoms worsened dramatically, Transcaucasus became battleground of the powerful Muslim – Ottoman and Safavid – Empires, while Georgia was completely isolated from the Christian world. Additionally, greatly accelerated process of the Islamization of the North Caucasian peoples, including Dagestani mountaineers – direct neighbours of Kakheti. From 1555 the Kingdom was a vassal of the successive dynasties of Persia[7] and to a much shorter period Ottoman Empire[8] but enjoyed intermittent periods of greater independence, especially after 1747.

Formally under the vassalage of the Safavid dynasty, Levan of Kakheti was desirous to diminish foreign influence over Georgia, stealthily sending Kakhetian detachments to his son-in-law Simon I of Kartli against the Qizilbashes in the 1560s. Alexander II, the astute son of the previous King, continued Levan's policy, switching sides during the Ottoman–Safavid war several times, simultaneously strengthening his realm. In addition, Alexander's army had to confront north-eastern neighbour of the Kingdom – Shamkhalate, whose rulers tried to wreak havoc to the borderlands of Kakheti, kidnapping peasants and looting countryside.[9] During the last quarter of the sixteenth century Kakhetian feudal army defeated Shamkhals’ undisciplined bands several times, killing hundreds of marauders.[10]

Throughout the fifteenth–eighteenth centuries Georgian Kings and Princes, including those of Kakheti, constantly tried to establish diplomatic relations with the Popes and Christian Monarchs of the West – Holy Roman Empire, Spain, France, Prussia, Naples etc. calling them for aid against the Ottoman and Safavid incursions. However, nothing came from these attempts, geographic distance and ongoing wars made it impossible for the Europeans to support fellow Christian nation. As a result Georgian political entities had to fight against Muslim invaders virtually alone, while geographical isolation greatly limited opportunity for the Georgian elites to come into contact with the epochal changes taking place in Europe during the early modern period.[citation needed]

If the political and military assistance from the Western Europe proved to be unrealistic, in the north Grand Duchy of Muscovy, freed from the Mongol-Tatar yoke in 1480, seemed as a steadfastly growing Orthodox superpower. Alexander I of Kakheti became the first Georgian King to establish formal diplomatic contact with the Russians, dispatching two embassies to Grand Duke Ivan III of Muscovy in 1483 and 1491.[11] In 1556, Astrakhan was conquered by Ivan the Terrible. After eleven years Terek-Town fort was built,[12] Russians became nearly direct neighbours of Kakheti. In 1563, King Levan, grandson of Alexander I, appealed to the Muscovites to take his realm under their protection against the Ottomans, and Safavids. Tsar Ivan IV responded by sending a Russian detachment to Georgia, but Levan, pressured by Iran, had to turn these troops back after several years. King Alexander II also appealed for Russian support against foreign encroachments. In 1587, he negotiated The Book of Pledge, forming an alliance between Kakheti and the Russian Tsardom. David I of Kakheti (1601–1602), the rebellious son of Alexander II, during his short reign reaffirmed loyalty to the foreign policy of his predecessors. However, as the Times of Troubles began in Russia, Georgian political entities could not count on Muscovite assistance in their struggle for independence.[11]

Seventeenth century: Abbas I's invasions, Teimuraz I, struggle for survival

[edit]

In 1605, Constantine, younger son of Alexander II, who was raised at the Safavid court and converted to Islam, according to Shah's secret instruction assassinated his father and brother. The assassination of the royal family and usurpation of the crown by Constantine I infuriated the Georgians, who rose in a rebellion under the direction of Queen Ketevan later that year. On October 22, 1605, the Kakhetian army routed the Qizilbash forces of Constantine, who was killed on the battlefield.[13] Caught by surprise, Abbas I grudgingly accepted the result of the 1605 Uprising and was forced to confirm sixteen years old Teimuraz I (1605–1648) – nemesis of the Safavids in the future – as a new King of Kakheti.

In 1612, the treaty of Nasuh Pasha was concluded, war with the Ottomans was temporarily over. From now on Shah Abbas I could attack eastern Georgia without hindrance – dethrone Christian Kings, establish Qizilbash khanates and deport or exterminate insubmissive Georgians from their homeland.[14] In October 1613, Abbas I moved his army to Ganja. Next spring, he turned on Kakheti, demanding Teimuraz's sons as hostages. After taking counsel, Teimuraz I sent his mother Ketevan and his younger son, Alexander, to Iran. The Shah insisted; reluctantly, the Kakhetians sent the heir, Levan. Shah Abbas I then demanded Teimuraz's attendance. At this point war broke out.[15] In 1614–1617, Abbas I led several campaigns against Kakheti and Kartli, massacred and deported hundreds of thousands ethnic Georgians to Iran, also despite stiff resistance and heavy defeat at Tsitsamuri[16] forced Teimuraz I to Imereti. Shah Abbas I castrated both sons of the obdurate King and savagely tortured and burned to death his mother Queen Ketevan on September 13, 1624.[17] Ketevan was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church and remains a symbolic figure in Georgian history. The story of her martyrdom was publicized in Europe, and several literary works were produced, including Andreas Gryphius’ Katharina von Georgien (1657).[18] Moreover, Shah sought to populate Kakheti with the Turkoman tribes.[19]

In 1624, Shah Abbas I turned his attention to Georgia again. Fearing a potential revolt, he dispatched some 35,000 men under Qarachaqay Khan and George Saakadze to subdue eastern Georgia. Although Saakadze had already served the Shah for twelve years, Abbas I didn't trust Georgian general completely and kept George's son, Paata, as a hostage. The Shah's anxiety was justified, since the Grand Mouravi had maintained covert communications with the Georgian forces and devise a plan to destroy the enemy army.[20] Saakadze surreptitiously united Kartli and Kakheti behind him.[21] He deviously ‘advised’ Qarachaqay Khan to split his forces into small groups and send them into Kakheti, while the major army camped near Martqopi.[22]

On March 25, 1625, Saakadze summoned the war council where he personally slew Qarachaqay Khan and Yusuf Khan of Shirvan, while his son, Avtandil, and his Georgian escorts killed other Qizilbash commanders, including Imam Verdi Khan, Qarachaqay's son.[23] Receiving a signal, Zurab Eristavi – another Georgian noble in Abbas's service – charged with his main forces, virtually annihilating leaderless Iranian troops.[24][25] Annunciation Day (25 March) brought an extraordinary victory – Saakadze's and Duke Zurab's army massacred 27,000 out of 30,000 strong Turkoman-Persian army, took their arsenal and besieged Tbilisi's citadel before the puppet-king Simon II (1619–1630) could arrive. Within days, all Kartli and Kakheti was in Georgian hands.

After that, Saakadze's army invaded neighbouring provinces of the Safavid Empire – plundering Ganja and razing to the ground countryside to the Araxes river, thus avenging Shah Abbas’ invasions.[26][27] Since the Georgian Uprising was sudden, Qizilbash tribes living in Karabakh were caught by surprise and had to flee further south hastily. Even though Georgians managed to capture thousands of Qizilbashes. As Saint Luarsab II of Kartli had already been martyred on the orders of the Shah in 1622,[28] Teimuraz I was invited from Gonio to take the crowns of Kartli and Kakheti, thereby uniting both Kingdoms.[25][29]

Abbas I, like Iran's and Turkey's chroniclers, was aghast at this debacle.[30] His counterattack came in June 1625, when another Qizilbash army numbering 40,000, led by Isa Khan and Kaikhosro-Mirza, entered in Kartli and bivouacked on the Marabda Field, while the Georgians were higher up in the Kojori gorge.[31] At the council of war, George Saakadze urged King Teimuraz I and other lords to remain in position, since descending into the valley would allow the Iranians to take advantage of their numerical superiority as well as firepower.[32] However, powerful lords were concerned about the enemy ravaging their estates and threatened to defect unless the battle was given at once, thus the Grand Mouravi was overruled.[33]

On July 1, 1625, Teimuraz I ordered the attack. The Iranians, armed with the latest weaponry, were well prepared for the assault, having dug trenches and deployed their troops in four lines, with the first kneeling, the second standing, the third on horseback, and the fourth on camels.[34][30][33] Georgians, lacking firearms, suffered heavy casualties, but the impetus of their attack pierced the Qizilbash lines and spread confusion among the enemy. As the Iranians began to flee, a small group of Georgian troops pursued them while others began to plunder the Qizilbash camp. At this moment, the Iranian reinforcement numbering 20,000, led by Shahbandeh Khan of Azerbaijan, arrived charging the befuddled Georgians;[35] in the resultant confusion, Prince Teimuraz Mukhranbatoni was killed but the rumor spread that King Teimuraz I had been killed, further demoralizing the Georgian host. The Georgians were defeated, losing about 10,000 killed and wounded,[30] including 900 mountaineers from the Duchy of Aragvi.[36] Among the dead were the nine brothers Kherkheulidze who defended the royal banner to the last, as well as the prominent nobles – Baadur Tsitsishvili and David Jandieri, nine Machabelis, seven Cholokashvilis, bishops of Rustavi and Kharchisho.[37] Furthermore, Zurab Eristavi, the mighty Duke of Aragvi, was severely wounded. The Iranians suffered heavy losses as well, losing some 14,000 men,[33] including Amir Guneh Khan of Erivan – deadly wounded by Manuchar III Jaqeli.[36]

Following the battle, Saakadze again led the Georgian resistance and turned to guerrilla war, eliminating some 12,000 Qizilbashes in the Ksani Valley alone.[33] Among the dead was Shahbandeh Khan of Azerbaijan, while Qazaq Khan Cherkes was captured. The Georgian Uprising of 1625 debunked Shah Abbas’ plans of destroying the Georgian states and setting up Qizilbash khanates in Kartli and Kakheti.[38] Losing half of his army forced Shah Abbas I to let vassals rule eastern Georgia. He abandoned plans to cleanse it of Christians.[30] George Saakadze (1942) is a Soviet Georgian historical drama film directed by Mikheil Chiaureli, depicting the heroic struggle of the Georgian nation against the Ottoman and Safavid hordes during the first quarter of the seventeenth century. The film is based on the six-volume novel, The Grand Mouravi (1937–1958), of Anna Antonovskaya.[citation needed]

Demographic, material, economic and cultural losses inflicted to the Kingdom of Kakheti by the hordes of the Qizilbashes, during the first quarter of the seventeenth century, were irreparable. Population of the Kingdom dwindled to 50,000–60,000, while Gremi and Zagemi were almost completely devastated and never fully recovered from the blow dealt by the invaders. Hundreds of villages, castles and churches were razed to the ground or badly damaged. Yet still, fierce resistance resulted in Georgians preserving statehood, most of their ethnic territories, as well as religion of the ancestors.[citation needed]

Dagestani peoples, encouraged by the Safavid officials, constantly attacked poorly defended countryside of Kakheti,[39] and massively migrated to the easternmost region of the Kingdom – Eliseni, on the left bank of the Alazani river.[40] Such a development led to a prolonged conflict between the Georgians and marauding Dagestani bands, greatly hampering revival of the Kakhetian Kingdom. Teimuraz I took an energetic measures against the Dagestanis’, suddenly attacked and decapitated the Sultan of Elisu, avenging for his participation in the Abbas I's Georgian campaigns.[41] Besides that Teimuraz I tried to reestablish Christianity in the westernmost part of Dagestan, between the mountainous Dido people, traditionally closely related with Kakheti. Despite some initial successes, efforts made by the King proved to be futile.[42]

During the next five years Teimuraz I got rid of his major rivals one by one – defeating Saakadze in the decisive battle of Bazaleti (1626) and assassinating Simon II and Zurab Eristavi, both in 1630. In 1632, he sheltered Daud Khan Undiladze, the Safavid governor of Ganja and Karabakh. After Abbas's death in 1629, once mighty clan of the Undiladze fell into disfavor and was destroyed on the order of the Shah Safi. In response, Daud Khan colluded with Teimuraz I, deceitfully leading detachment of the Qajars to the Iori river to be massacred by Kakhetians.[43] Additionally, Teimuraz's army immediately invaded Arran and Karabakh several times, pillaging Ganja twice.[44]

In 1633, Safavid counterattack came, the Qizilbash army led by Rostom Khan, uncle of the late Simon II, forced Teimuraz I to Imereti. Rostom (1633–1658) became the new King of Kartli. However, in the following year, to the disappointment of the Shah, Teimuraz I managed to reestablish himself in the Duchies of Aragvi and Ksani. Moreover, by 1638, Kakheti was under full control of the unruly King. During the 1630s Teimuraz I renewed his attempts to establish close ties with Russia. In 1639, he petitioned the Tsar of Russia for help and signed an oath of loyalty.[45] However, no military aid had arrived.

In 1642, Teimuraz I conspired with Catholicos-Patriarch of eastern Georgia – Eudemus I and Kartlian nobles, to assassinate Rostom of Kartli, when the Muslim King was relaxing unguarded in the country. After that, Teimuraz I had to capture Tbilisi, expel Qizilbashes and unite eastern Georgian Kingdoms. However, a conspirator betrayed the plot. Rostom had the Catholicos-Patriarch arrested and imprisoned at the citadel of Tbilisi, where he was strangled.[46] Eudemus I was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church as a holy hieromartyr. Six years later stubborn King of Kakheti was finally ousted from the power, losing the heir – Prince David, in the fateful battle of Magharo.[47] Rostom, loyal vassal of the Shah, became the new ruler of Kakheti.

Taking shelter in Imereti, deposed Kakhetian King had his grandson Heraclius sent to the Russian court. In 1658, Teimuraz I travelled to Moscow, thus becoming the first Georgian King to visit Russia. In 1661, seventy-two years old King was captured during the Imeretian campaign of the King of Kartli, Vakhtang V (1658–1675). Teimuraz I was escorted as an honoured prisoner through Kartli to Shah Abbas II's court – the Shah urged him to accept Islam, offered him meat on a fast day and, when Teimuraz I declined, threw wine in his face and imprisoned him in Astrabad by the Caspian.[48] Here, the most valiant Georgian King of the seventeenth century died in 1663. Teimuraz I was buried in the Alaverdi Monastery.

In 1656, Shah Abbas II made another attempt to settle Turkoman tribes in Kakheti. As a result, in 1659, Georgians revolted again, tens of thousands Turkomans were massacred, or forced to leave Kakheti. The location, Gatsqvetila (‘Exterminated’), where the most Qizilbashes were slaughtered, became infamous.[48] By 1660, Shah acknowledged his failure in Kakheti. However, Safavids also threatened retaliation if rebel leaders did not surrender. Bidzina Cholokashvili, Shalva and Elizbar Eristavis of Ksani chose to sacrifice their lives to avoid further bloodshed and traveled to Isfahan, where they were executed. The events of the 1659 Uprising produced numerous oral traditions, especially in mountainous regions of eastern Georgia – Tusheti, Pshavi and Khevsureti, where poems dedicated to local heroes became popular. In the nineteenth century, Vazha-Pshavela used these traditions to create one of his finest poems, Bakhtrioni (1892), while his fellow writer Akaki Tsereteli produced another classic of Georgian literature, Bashi-Achuki (1896).[49] Bashi-Achuki (1956) is also a Soviet Georgian historical drama film directed by Leo Esakia.

In 1664, Archil II (1664–1675), the eldest son of the Kartlian King Vakhtang V, was confirmed as a new King of Kakheti, nominally converting to Islam. Eleven years of the Archil's reign proved to be the most successful period of the calamitous seventeenth century. Archil II managed to start a long process of the revival of Kakheti.[50] During his reign tens of deserted villages were repopulated, churches and monasteries repaired, castles rebuilt. In addition, Telavi – insignificant town during the fifteenth–seventeenth centuries – emerged as a new political and urban center of the Kingdom. Effectively exploiting military resources of his father's realm, Archil II organized several victorious expeditions in Dagestan, forcing mountaineers to submission.[51] As a result, during the reign of Archil II inroads of the Dagestani bands decreased significantly. However, in 1675, he had to leave Kakheti, while Heraclius I was forced to stay in Isfahan for years, before his nominal conversion to Islam.

From 1676 to 1703 Kakheti was put under direct control of the Safavid appointed khans, whose authority being merely nominal. Iranian khans, unable to deal with the Georgian nobility backed by restive vassal of the Safavids George XI of Kartli (1676–1688; 1703–1709), tried to weaken aristocratic resistance by encouraging further incursions and migration of the Dagestanis’ into Kakhetian lands.[52]

Eighteenth century: Heraclius II, political and cultural revival, twilight of the Kartli-Kakhetian Kingdom

[edit]

In 1703, Kakhetian branch of the house of Bagrationi was restored, ruling as the vassals of the degenerating Safavid dynasty. During the next twenty years Heraclius I (1675–1676; 1703–1709) and David II (1709–1722) had to deal with the incessant Dagestani inroads. Despite some initial successes, Eliseni, the easternmost region of the Kingdom, was irrevocably lost in the 1710s,[53] and free communities of the mountaineers, known as Djaro-Belokani, were established, while Georgian peasants living there had to leave or to Islamize gradually. They who chose the latter, became known as Ingiloys.

In 1722, Constantine II (1722–1732), the illegitimate son of Heraclius I, became the new King of Kakheti. In the next year, Shah Tahmasp II ordered him to remove from power Vakhtang VI of Kartli, who adopted an anti-Safavid policy and made an alliance with Russia, which proved to be unsuccessful. Constantine II of Kakheti, reinforced by the Transcaucasian Tatars and Dagestanis, invaded Kartli and captured Tbilisi on May 4, 1723. Defeated King of Kartli and his supporters fled to Shida Kartli. The same year, the Ottoman army marched against the Constantine II, who was unable to stop it and offered to negotiate. The Ottomans entered Tbilisi on June 12, 1723, deceiving and imprisoning King of Kakheti during the negotiations. Fortunately for him, Constantine II managed to escape to his realm. After Vakhtang VI of Kartli immigrated to Russia in 1724, King of Kakheti became the sole leader of the anti-Ottoman resistance in eastern Georgia. Since Safavid Iran was on the verge of collapse, nominally Muslim Constantine II decided to return to the centuries-old pro-Russian foreign policy of his forefathers and offered to place Kartli and Kakheti under the Russian protection. However, Peter the Great, as well as his successors had no intention to start a new war against the Ottomans.[54]

Meanwhile, Ottoman Empire skillfully used coreligionist Sunni Dagestanis against recalcitrant Georgian King, encouraging them to put constant pressure on Kakheti. On September 26, 1724, the Ottomans defeated Constantine's army in the fierce battle of Zedavela, while Dagestani bands devastated countryside. As a result, Constantine II had to find shelter in Pshavi. Yet still, in 1725, Georgians managed to drive marauding bands of the mountaineers out of Kakheti. By 1730, Kakhetian King was forced to recognize Ottoman supremacy and agreed to pay tribute. Additionally, Constantine II, indifferent to religion, converted from Shia to Sunni Islam. Seven years long resistance of Georgians resulted in invaders abandoning initial plan of annexation of Kakheti, as the Ottoman Porte had done in Samtskhe-Saatabago at the turn of the seventeenth century. On December 28, 1732, the Ottomans, never fully confident in Constantine's loyalty, murdered Kakhetian King in a treacherous way, inviting him to negotiate.[54]

Constantine II was succeeded by Teimuraz II (1732–1744), the only Christian son of Heraclius I. With the accession of Teimuraz II to the throne forty years of Muslim Kings ruling period (1664–1675; 1703–1732) was over. In 1733, Teimuraz II reluctantly recognized suzerainty of the Sultan, only to attack his forces in the next year. The Turks, caught by unawares, were defeated in the bloody battle of Magharo.[55]

A shrewd statesman, Teimuraz II tried to use Qizilbashes to his advantage and supported Tahmasp Qoli Khan in his campaigns to restore Iranian dominance in eastern Transcaucasus, in the 1730s. Initially, Tahmasp Qoli Khan already as Nader Shah, distrusted the stubborn King, who refused to convert to Islam even after detainment. However, the Shah, preoccupied by war on India, conceded that a Christian King would best keep Kartli and Kakheti peaceful and spare him from fighting on two fronts. First, he took with him to Iran Teimuraz II, his son Heraclius and his daughter Ketevan as hostages: Nader Shah married Ketevan to a relative, and enlisted Heraclius, who had military genius, for the Indian front. Meanwhile, in 1738, Teimuraz II, supported by the Qizilbashes, came back in his realm.[56] He managed to suppress the anti-Iranian rebellion led by the influential Kartlian noble, Givi Amilakhvari,[55] and consolidate his power in Kartli, thus de facto uniting eastern Georgian Kingdoms.

In 1744, Nader Shah confirmed Teimuraz II and his son Heraclius II (1744–1762) as the kings of Kartli and Kakheti and allowed them to perform Christian coronations.[57] Father and son were crowned at the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral on October 1, 1745 – the first Christian coronation of the eastern Georgian kings in over a century.[58]

In 1762, the Kakhetian Kingdom was united with the neighboring Georgian Kingdom of Kartli into the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti under King Heraclius II. Following the Treaty of Georgievsk and the sack of Tbilisi by Agha Mohammad Khan, in 1801 the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti was annexed to the Russian Empire. Russian suzerainty over Kakheti and the rest of Georgia was recognized by Qajar Iran in the 1813 Treaty of Gulistan.[59]

1801–1917: Kakheti within the Russian Empire, uprisings, modernization, Georgian national awakening

[edit]Loss of independence and establishment of the Imperial administration led to an imminent uprisings. In 1802, Kakhetian nobles revolted, insurgents planned to restore kartli-Kakhetian Kingdom. However, Russians quickly responded and crushed the rebellion.[60] In 1810–1811, Kakheti suffered from poor harvests and plague, which led to food shortages and high prices. Despite the hardship, Russian officials forced the peasantry to sell their remaining produce to the state at a low price. As the Russian troops began requisitioning supplies, a peasant uprising flared up in the village of Akhmeta on January 31, 1812. The insurgents defeated Russians in the hard-fought battle of Bodbiskhevi, killing 2 officers and 212 soldiers,[61] captured and slaughtered the entire Russian garrison of Signagi and later seized Telavi, Anaga, Dusheti, and Pasanauri. After some hesitations the rebels were supported by the local nobility and clergy. They proclaimed a prince Grigol Bagrationi, great-grandson of Heraclius II and grandson of George XII as the King of Kartli-Kakheti.[62] The revolt soon spread to Kartli, and the Russian forces lost more than 1,000 men in clashes with the insurgents. The rebellion continued throughout 1812 until the superior Imperial army, led by governors of Caucasus – Italian-born Marquis de Paulucci and Nikolay Rtishchev finally defeated it and pacified the region by early 1813.[63]

In 1918–1921 Kakheti was part of the independent Democratic Republic of Georgia, in 1922–1936 part of the Transcaucasian SFSR and in 1936–1991 part of the Georgian SSR. Since the Georgian independence in 1991, Kakheti has been a region of the republic of Georgia.[citation needed]

Winemaking in Kakheti

[edit]

The Kakheti Wine Region is located in the eastern part of Georgia and comprises two river basins, Iori and Alazani. These rivers have a significant influence on the character of Kakhetian wines. Kakheti is bordered on the west by another very important wine region of Georgia - Kartli. Together with the location, the climatic conditions of the region play an essential role in the formation of Kakheti wines. Kakheti vineyards are cultivated at an altitude of 250–800 meters above sea level. We can find both humid subtropicals as well as continental climates in the region. Kakheti terroir provides ideal conditions for both local varieties and international wine varieties as well. When talking about the Kakheti wine region, the first thing that comes to mind is Rkatsiteli and Saperavi grapes. These two wine varieties have become the face of the region and Georgia. With the increase in the awareness of Georgian wine, the interest in these varieties is growing, so do not be surprised if you encounter these Kakhetian wine varieties in different wine regions in the world.

Travel information

[edit]

The travel infrastructure in Kakheti is fast developing, since it is the most visited region of Georgia. One can choose to stay in a guest house, in a small and comfortable hotel, or a beautiful boutique-style hotel while traveling in this region. Telavi and Signagi are the most visited towns. Signagi was renovated three years ago. Until recently there were only some family hotels (simple rooms in a family-owned house with a shared bathroom), but now Signagi features several hotels.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Population by regions". National Statistics Office of Georgia. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ "Regional Gross Domestic Product" (PDF).

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ Michael Mainville (2007-05-03). "Ancient monastery starts modern-day feud in Caucasus". Middle East Times. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ^ Kakheti municipalities Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine. Regional Government of Kakheti. Retrieved on May 22, 2009

- ^ Allen 1970, p. 159.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, pp. 176, 179, 227.

- ^ Allen 1970, p. 216.

- ^ Allen 1970, pp. 137–138, 217–218.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2007, p. 550.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 173.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 238.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 189.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 190.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 191.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 192.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 397.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 26.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 448.

- ^ Archili 1989, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 193.

- ^ Archili 1989, p. 446.

- ^ Egnatashvili 1989, p. 780.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2007, p. 449.

- ^ Archili 1989, pp. 446–447.

- ^ Egnatashvili 1989, pp. 780–781.

- ^ Egnatashvili 1989, pp. 769–771.

- ^ Archili 1989, pp. 447–448.

- ^ a b c d Rayfield 2013, p. 194.

- ^ Archili 1989, pp. 448–449.

- ^ Archili 1989, p. 450.

- ^ a b c d Mikaberidze 2007, p. 446.

- ^ Archili 1989, p. 454.

- ^ Egnatashvili 1989, p. 782.

- ^ a b Archili 1989, p. 456.

- ^ Archili 1989, p. 455.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Lamberti 2020, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Witsen 2013, p. 206.

- ^ Egnatashvili 1989, p. 790.

- ^ Archili 1989, p. 477.

- ^ Archili 1989, pp. 471–472.

- ^ Lamberti 2020, pp. 214–220.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 199.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 200.

- ^ Egnatashvili 1989, p. 802.

- ^ a b Rayfield 2013, p. 210.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 136.

- ^ Vakhushti 1973, pp. 603–604.

- ^ Vakhushti 1973, p. 605.

- ^ Vakhushti 1973, p. 612.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2007, p. 239.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2007, p. 617.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 232.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 618.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 233.

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond p 728 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Potto 1887, p. 484.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 272.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2007, p. 386.

Sources

[edit]- Allen, William E. D. (1970). Russian Embassies to the Georgian Kings 1589 to 1605. Volume I. Cambridge University Press.

- Bagrationi, Archili (1989). The Dialogue between Teimuraz and Rustveli. Nakaduli.

- Bagrationi, Vakhushti (1973). Description of the Kingdom of Georgia. Sabchota Sakartvelo.

- Egnatashvili, Beri (1989). The New Georgian Chronicle. Nakaduli.

- Lamberti, Arcangelo (2020). Colchide Sacra. Artanuji.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2007). Historical Dictionary of Georgia. Scarecrow Press.

- Potto, Vasily (1887). The Caucasian War in Different Essays, Episodes, Legends, and Biographies. volume I. V. A. Berezovski.

- Rayfield, Donald (2013). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. Reaktion Books.

- Witsen, Nicolaes (2013). Noord en Oost Tartarye. Universali.

External links

[edit]- Kakheti regional administration website

- Travel guide to Kakheti wine region

- Armenians in Kakheti (Հայերը Կախեթում) PDF. In Armenian.