Shadoof

A shadoof or shaduf[1] is an irrigation tool that is used to lift water from a water source onto land or into another waterway or basin. It is highly efficient, and has been known since 3000 BCE.[citation needed]

The mechanism of a shadoof comprises a long counterbalanced pole on a pivot, with a bucket attached to the end of it. It is generally used in a crop irrigation system using basins, dikes, ditches, walls, canals, and similar waterways.[2]

History

[edit]

One theory states that the shadoof was invented in prehistoric times in Mesopotamia as early as the time of Sargon of Akkad (around 24th and 23rd centuries BCE). The earliest evidence of this technology is a cylindrical seal with a depiction of a shadoof dating back to about 2200 BCE. Then, it is believed that the Minoans adopted this technology; evidence suggests the use of shadoofs as early as around 2100-1600 BCE. The shadoof appeared in Upper Egypt sometime after 2000 BC, most likely during the 18th Dynasty.[3] Around the same time, the shadoof reached China.

Some historians believe the Egyptians were the original inventors of the shadoof. The theory states that the shadoof originated along the Nile, using tomb drawings illustrating shadoofs at Thebes dating from 1250 BCE as evidence.[4]

An alternative origin theory states that shadoof originated from India around the same time as in Mesopotamia. This theory owes to the fact that the shadoof was well spread in India; however, there is little to no other evidence that makes this theory any stronger.[3]

It is still used in many areas of Africa and Asia and is very common in rural areas of India and Pakistan, such as the Bhojpuri belt of the Ganges plain, In Europe, they remain common in Germany and Hungary's Great Plain, where they are considered a symbol of the region. They are also well widespread throughout Eastern Europe in countries like Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic states.

Design, construction, and efficiency

[edit]The shadoof is easy to construct and is highly efficient in use.[5] It consists of an upright frame on which is suspended a long pole or branch, at a distance of about one-fifth of its length from one end.[5] At the long end of this pole hangs a bucket, skin bag, or bitumen-coated reed basket. The bucket can be made in many different styles, sometimes having an uneven base or a part at the top of the skin that can be untied. This allows the water to be immediately distributed rather than manually emptied. The short end carries a weight made of clay, stone, or a similar material, which serves as the counterpoise of a lever. The bucket can be lowered by the operator using their own weight to push it down; the counterweight then raises the full bucket without effort.[5][6]

The implementations vary from region to region. The frame can consist of a single pole or a pair, and the buckets can be attached in multiple different ways, from being tied to a rope to being attached to a thinner stick.[3]

With an almost effortless swinging and lifting motion, the waterproof vessel can be used to scoop up and carry water from a body of water (typically, a river or pond) onto land or to another body of water. At the end of each movement, the water is emptied out into runnels that convey the water along irrigation ditches in the required direction.[6] The device is capable of lowering the force levels required of operators to the extent that the performance tends to be limited by the energy processing capacity of the operator and not necessarily muscle fatigue.

The shadoof has a lifting range of 1 to 6 meters. A study of efficiency in various sites in Chad has shown that one man can lift 39 to 130 liters per minute over heights of 1.8 to 6.2 m, resulting in water-lifting power levels of 26.7 to 60.1 W. Its efficiency has been calculated at 60%.[4][7]

A study done in Nigeria also indirectly assessed energy usage through heart rate, serving as the physiological metric. Through this approach, it was discovered that making suitable adjustments to the shadoof decreased energy consumption from approximately 109 to 71 watts (equivalent to 6.56 to 4.27 kilojoules per minute). This reduction enables a farmer to engage in prolonged work without necessitating frequent rest breaks.[7]

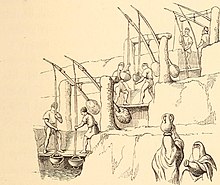

Social effects

[edit]Across numerous cultures, shadoofs have symbolized collective effort.[7] In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, for instance, the multi-tiered shadoof systems allowed the movement of water to higher levels through teamwork.[8] Together with other irrigation technologies, shadoofs not only helped establish reliable methods of agriculture for growing civilizations but also influenced cultural elements.[9]

The accessibility and utilization of shadoofs have been linked to class. During the Egyptian Middle Empire and the New Kingdom, pleasure gardens featuring shadoof irrigation became a hallmark of luxury residences and consequently a status symbol.[10] Although not directly, shadoofs contributed to creating a class system, a barrier for some. At the same time, shadoofs have remained essential for those with limited resources to support their livelihoods on large-scale farms around the Nile. Even in the present day, many communities worldwide lack access to more sophisticated water technologies, making shadoofs an indicator of socio-economic standing and a certain measure of societal development. The technology's reliability, despite its antiquity, often gets overlooked.[7]

The geographic spread of shadoofs is impressive. In regions where irrigation is imperative, such as Egypt, India, and parts of sub-Saharan Africa, shadoofs have played a crucial role in enabling agriculture to thrive in water-scarce areas. Shadoofs have empowered marginalized communities by providing them with the means to secure their sustenance, breaking the barrier of food insecurity even in the modern age.[4][7]

Gender roles have also undergone a transformation, with women frequently assuming shadoof operation.[11] The ease of use of the shadoof empowered women to play a more active role in farming. It is fair to acknowledge that shadoofs contributed to normalizing women's increased independence and participation in less physically demanding, and therefore more “socially acceptable”, aspects of food production.[11]

The ease of use of the shadoof is perhaps its most important feature. Studies have shown that it is impressively efficient, given the simplicity of its design. Still, it is essential to recognize that shadoofs, while easing the physical demands of water retrieval, require manual labor, posing a barrier for individuals with certain physical disabilities.[4] This underscores the need for more inclusive adaptations of this ancient technology.

Names

[edit]- Shadoof or shaduf comes from the Arabic word شادوف, šādūf.

- It is also called a lift,[5] well pole, well sweep, or simply a sweep in the US.[12] A less common English translation is swape.[13]

- Picotah (or picota) is a Portuguese loan word.

- It is also called a jiégāo (桔槹) in Chinese.

- The Tamil name is thulla (துலா), while the Telugu name is ethaamu (ఏతాము) or ethamu (ఏతము).

- It was also known by the Ancient Greek name kēlōn (κήλων) or kēlōneion (κηλώνειον); this term (קילון) is also borrowed in Mishnaic Hebrew.

- In Ukrainian, it is called krynychnyi zhuravel (криничний журавель, "well crane") for its shape; it is also known as zvid (звід).

- In Hungarian, it is known as gémeskút (literally, "heron wells").

- In Croatian, it is known as đeram (from Turkish, germe).

Gallery

[edit]-

Shadoof in Egypt

-

Shadoof in Pyrohiv Museum, Ukraine

-

Shadoof in Belarus

-

Shadoof in Turkey

-

Shadoof in Germany

In art

[edit]-

Ancient wall painting in Egypt

-

Painting by Károly Sterio, 1855

-

Painting by Ivan Sokolov, 1864

In heraldry

[edit]The use of shadoofs in certain areas influenced heraldry.[9] Below are some examples of heraldic elements of various subdivisions.

References

[edit]- ^ "Performance Characteristics of the Shaduf: A Manual Water-Lifting Device". Asae.frymulti.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ^ Roberts, John (2013). Allen Lane (ed.). The Penguin History of the World. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1846144431.

- ^ a b c Yannopoulos, Stavros I.; Lyberatos, Gerasimos; Theodossiou, Nicolaos; Li, Wang; Valipour, Mohammad; Tamburrino, Aldo; Angelakis, Andreas N. (September 2015). "Evolution of Water Lifting Devices (Pumps) over the Centuries Worldwide". Water. 7 (9): 5031–5060. doi:10.3390/w7095031. ISSN 2073-4441.

- ^ a b c d t. h. Mirti; w. w. Wallender; w. j. Chancellor; m. e. Grismer (1999). "PERFORMANCE Characteristics of the Shaduf: A Manual Water-Lifting Device". Applied Engineering in Agriculture. 15 (3): 225–231. doi:10.13031/2013.5769. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ a b c d D. T. Potts (2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. John Wiley & Sons. p. 264.

- ^ a b Faiella, Graham (2006). The Technology of Mesopotamia. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 27. ISBN 9781404205604.

- ^ a b c d e Nwuba, E. I. U. (1989-05-01). "Ergonomic study of shadoof irrigation in northern Nigeria". Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research. 43: 137–147. doi:10.1016/S0021-8634(89)80013-7. ISSN 0021-8634.

- ^ "Human Nature, Technology & the Environment". fubini.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ a b Crabben, Jan van der. "Agriculture in the Fertile Crescent & Mesopotamia". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ "Gardens in Ancient Egypt". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ a b Fredriksson, Per G, and Satyendra Kumar Gupta. “Irrigation and Culture: Gender Roles and Women’s Rights.” Econstor.eu, 7 Oct. 2020, www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/225005/1/GLO-DP-0681.pdf

- ^ Knight, Edward Henry. Knight's American mechanical dictionary. Vol. 3. New York, Hurd and Houghton: Riverside Press, 1877. 2,468. Print.

- ^ "Definition of "Swape"". Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary. MICRA Inc. Retrieved 2007-04-25.