José María Valiente Soriano

José María Valiente Soriano | |

|---|---|

| Born | José María Valiente Soriano 1900[1] Chelva, Spain |

| Died | 1982 Valdecilla, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation(s) | Lawyer, politician |

| Known for | Politician |

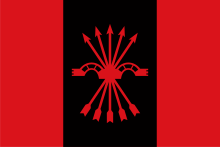

| Political party | AP, CEDA, CT, UNE, DDE |

José María Valiente Soriano (1900-1982) was a Spanish politician. He commenced his career in Acción Nacional and gained recognition as leader of Juventudes de Acción Popular, the youth branch of CEDA. In 1935 he joined Carlism; his political climax fell on the period of 1955-1967, when he was leading the mainstream Traditionalist organisation. After 1971 he unsuccessfully engaged in buildup of conservative monarchist groupings. He served in the Republican parliament during two terms between 1933 and 1936; between 1967 and 1977 during two terms he held a mandate in the Francoist Cortes. In 1937-1942 he was member of Consejo Nacional of Falange Española Tradicionalista.

Family and youth

[edit]

None of the sources consulted provides information on Valiente's distant ancestors; it is known that his paternal grandfather José Valiente was related to a Murcian town of Yecla, but it is not known what he was doing for a living.[2] His son and Valiente's father, also José Valiente (died 1938),[3] in the late 1870s frequented the local Yeclan Colegio de los Padres Escolapios, and obtained “bachillerato de arte” in 1881.[4] He then studied law at an unspecified university and at least since the mid-1890s served as a notary in Yecla.[5] He married Micaela Soriano e Ibáñez; nothing is known either about her or her family except that her parents were also the natives of Yecla.[6] The couple had 3 children; José Maria was only son.[7] They initially settled in the Valencian town of Chelva, where Valiente served as a notary.[8] In 1900 the family moved to Valencia, where Valiente was admitted to the local notary corps.[9] He served in the Levantine capital for some 20 years; in 1920[10] or 1921 he moved to Madrid and kept practicing as a notary.[11]

The young José María was brought up in Valencia; in the mid-1910s he was frequenting the local Colegio de San José, run by the Jesuits,[12] and was doing well;[13] in 1917 he obtained bachillerato at Instituto de Valencia.[14] Following preparatory courses in Murcia[15] he then enrolled at law in Universidad Central in Madrid and followed the licenciatura curriculum between 1917 and 1921.[16] Sometime in the early 1920s Valiente Soriano moved to Italy to pursue his academic career in Università di Bologna, where in 1923 he passed the Esame di Laurea in Giurisprudenza.[17] It is not clear whether back in Spain Valiente was further related to Universidad Central, as he got his title of licenciado en derecho confirmed by the Madrid alma mater in 1927.[18] In the late 1920s he commenced work as auxiliary professor at Central; at the same time he practiced as abogado.[19]

In 1933[20] Valiente married a girl from Santander, Consuelo Setién Rodríguez (died 1986);[21] she was descendant to a family of noble Cantabrian landowners[22] and would later claim the title of Marqués de Pelayo.[23] The couple settled in Madrid at calle General Castaños 4[24] and had at least 3 children, born in the 1930s; Lucía,[25] Rosa Blanca[26] and José Ignacio Valiente Setién.[27] None of them became a public figure, which is also the case of Valiente's grandchildren. Among other relatives the best known is his nephew[28] Alfredo Prieto Valiente, who was an important Asturian politician and in the years of 1977-1979 served as the Unión de Centro Democrático deputy to the Constituent Cortes.[29] One more Valiente's sister married into the aristocratic Toll-Messia family[30] and his another nephew, Fernando Toll-Messia y Valiente, was the XIII. Conde de Cazalla del Río.[31]

In Christian organizations (1924-1935)

[edit]

In his youth Valiente's father was a liberal,[32] though in the 1920s he moved to more conservative positions and supported the Primo de Rivera dictatorship.[33] The first information on Valiente Soriano's political engagements comes from 1922: he entered the Madrid branch of Confederación Nacional de Estudiantes Católicos.[34] In 1924 and jointly with Gil Robles he co-founded Vanguardia Social Popular, designed as a youth branch of Partido Social Popular.[35] In 1927, Valiente set up Juventud Católica de España, the ostensibly apolitical grouping concerned with defence and dissemination of Catholic values among the youth;[36] in 1931 it was federated with Acción Católica, a broad organization of lay Catholics led by Ángel Herrera Oria. Later the same year, once the militantly secular course of the Republic began to take shape, he moved to politics by co-founding Acción Nacional (which in 1932 changed its name to Acción Popular), a broad though heterogeneous conservative alliance, and became the vicepresident of its first National Committee.[37] Since Acción Catolica banned its members from holding political party leadership roles, Valiente had to resign from the JCE leadership.[38]

In 1933, Valiente proceeded to build the Acción Popular youth organisation, Juventudes de Acción Popular, and became its president.[39] Soon afterwards AP transformed itself into Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas. JAP, now forming a juvenile branch of CEDA, retained its name and structure; Valiente continued to lead the organisation and became one of the national CEDA chieftains.[40] Under his guidance, Juventudes became an aggressively anti-Lefist and pro-authoritarian group,[41] though falling short of a typical "shirt organization" and denying similarity to Fascism.[42] During the 1933 elections to the Cortes, Valiente, thanks to his Cantabrian family links, negotiated a place on the local Unión de Derechas Agrarias list of candidates[43] and was comfortably elected from the Santander-Cantabria district.[44]

In early 1934, Valiente at least twice secretly travelled to France to speak with Alfonso XIII.[45] His aim was to negotiate the terms of modus vivendi between the monarchists and CEDA, and specifically to ask that for the deposed king refrains from any statements that might impair CEDA's political fortunes.[46] It is not exactly clear to what extent this mission was agreed with the party leader José Gil-Robles, since the two gave conflicting accounts of the incident, but it is usually accepted that the latter was at least approvingly aware.[47] When the news of the Fontainebleau talks leaked to the press CEDA, the party which despite repeated declarations of loyalty towards the Republic was customarily accused of anti-Republican designs by the Left, found itself cornered and embarrassed. Eventually, the official version adopted by CEDA presented the incident as a monarchist plot within the organization. Valiente, apparently with his consent, was made a scapegoat and was expelled from the party.[48] It is not unlikely that the militancy of JAP, perceived by the more acquiescent cedistas as compromising, might have contributed to the harsh line taken against Valiente. He had to leave JAP as well, replaced as its leader by José María Perez de Laborda.[49]

Carlist: Republic and War (1935-1939)

[edit]

In late 1935, amid a blaze of publicity, Valiente decided to join Comunión Tradicionalista.[50] For the Carlists, he was a valuable acquisition. The JAP militancy and the monarchist episode, embarrassing to the loyalist CEDA, were welcome credentials for the Traditionalists, who made little secret of their intention to do away with the godless regime as soon as possible.[51] From this moment he became a vehement critic of CEDA, indulging in invectives against his former party mates.[52] During the 1936 elections to the Cortes, he ran on the Carlist ticket from the rather conservative Burgos constituency[53] and was elected.[54] He was not noted as a particularly active deputy; his focus was rather on propaganda.[55] His already notable standing on the national political scene was demonstrated when Valiente carried the coffin at the funeral of José Calvo Sotelo.[56]

During the anti-Republican conspiracy, Valiente's role was reduced to negotiations with the would-be Alfonsist allies in the Burgos province, where he resided during the coup of July 18. He became member of the Carlist wartime executive Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra, where as member of Seccion Administrativa[57] he took care of religious affairs.[58] When Franco expulsed the Carlist leader Manuel Fal Conde from Spain, Valiente acted as his informal substitute.[59] In 1937, facing Franco's pressure to unite the Carlists and Falange, he took part in two crucial meetings of the Carlist executive, in February in Insua[60] and in March in Burgos.[61] Initially he seemed to have been among hardline falcondistas, but later tended to cautious endorsement of compliance[62] and engaged in talks on details of the merger, apparently in hope that some genuine understanding might be achieved.[63]

When Unification Decree was made public Valiente resigned his post as secretary of the Junta; he admitted that the merger conflicted with his feelings and that "there is no moral unity" between the merged parties,[64] but argued that given the circumstances, it had to be accepted.[65] In May 1937 he was among 9 Carlists nominated to provincial FET jefaturas[66] when made the party leader in Burgos;[67] in October as one of 11 Carlists he entered the 50-member Consejo Nacional of the new organization (though not the Junta Politica).[68] More than amalgamation within a motley grouping artificially created by the military, he feared the breakup of Carlism.[69] Having personal authorisation of the regent-claimant Don Javier, Valiente remained in the Falangist Consejo Nacional,[70] but he refused the offer of Rodezno, who assumed the Ministry of Justice in the first Francoist cabinet of 1938 and asked Valiente to be his sub-secretary (the post went to Luis Arellano instead).[71] As member of Consejo Valiente was bombarded with letters of protest and requests for assistance on part of the Carlists who complained about Falangist domination, marginalisation of Traditionalism and personal persecutions; however, there was almost nothing he could have done about it.[72]

Early Francoism (1939-1955)

[edit]

In 1939 Franco re-appointed Valiente to the new, 2nd Falangist Consejo Nacional.[73] However, in the early 1940s his official Francoist engagements were getting terminated; at unspecified time he ceased as the FET provincial jefe in Burgos, and in 1942 he was not appointed to the 3rd Falangist Consejo Nacional.[74] Save for some religious engagements,[75] the press ceased to mention his name. In the early 1940s Valiente decided to re-launch his academic career and served as auxiliar temporal at the Law Faculty in Madrid.[76] In 1942 he entered the selection process for the post of chair of Civil Law and in 1943 was nominated catedrático numerario in the Universidad de La Laguna in the Canary Islands.[77] In early 1946 he applied for transfer to the parallel position in Universidad de Sevilla; however, when admitted he agreed a swop with Miguel Royo Martínez from Zaragoza. He moved to Aragón, but did not complete the full annual academic cycle. In 1947 Valiente requested unpaid leave. The same year he vacated the post, though formally he remained related to the Zaragoza University;[78] he went on practicing as a lawyer.[79]

Until 1942, when Franco ignored Don Javier's proposal of forming a Carlist-Francoist government, Valiente seemed to hope for a compromise. In 1939 he co-signed Manifestación de los Ideales, a documented addressed to Franco which urged implementation of Traditionalist features;[80] in 1943 he co-signed another one, Reclamación de Poder, this time explicitly referring to instauration of the traditionalist monarchy.[81] In 1945 he attended a grand Carlist anti-Francoist demonstration in Pamplona and delivered an address from the balcony;[82] afterwards he was detained by security and expected facing the firing squad;[83] eventually the sanctions adopted were relatively mild, especially compared to the terror employed against the Left.[84] As one of the key mid-age Carlist followers of Don Javier and his Jefe Delegado Fal Conde, Valiente was courted by Conde Rodezno. The latter invited him to join the juanistas, the group notionally loyal to the regency, but pressing the candidacy of Don Juan, the Alfonsist claimant, as the prospective Carlist king. Valiente refused to adhere.[85]

In 1947 Valiente took part in the informal meeting of the Carlist executive, the first one since 1937;[86] he was nominated vice-president of re-established Carlist Consejo Nacional, effectively the second-in-command within the organization.[87] Highly skeptical about any would-be dynastical agreement Valiente remained loyal to Don Javier; in 1951 he welcomed the claimant in his Madrid home.[88] However, he became somewhat less enthusiastic in 1952, when Don Javier made declarations generally understood as termination of the regency and assumption of his own claim to the throne. Since the early 1950s at meetings of the Carlist command layer Valiente started to make references about "new political situation", thought to be hints about the need to seek rapprochement with the regime.[89] Together with Jose Maria Arauz de Robles and Jose Luis Zamanillo, within Carlism he was soon getting perceived as an advocate of "tendencia colaboracionista".[90]

Leader: ascent (1955-1963)

[edit]

Around the mid-1950s, the growing feeling among the javieristas was that the intransigent opposition, pursued by Manuel Fal Conde, produced few if any results. Don Javier seemed to agree.[91] Following the resignation of Fal Conde, in 1955 he created Secretariado General, a new collegial governing body of the movement, naming Valiente its provisional president.[92] Consistently opposing the plans of monarchical union, pursued by José María Arauz de Robles, Valiente engineered a more collaborative approach towards Francoism.[93] The time seemed particularly opportune in 1957, when totalitarian plans of the Falangist leader José Arrese were rejected by Franco; the dictator started to make references to Traditionalism and to movimiento-comunión. The law on Principios Fundamentales del Movimiento, adopted in 1958, declared Spain to be a Monarquía Tradicional.[94]

The new strategy of posibilismo was welcomed with mixed feelings among the Carlists; older regional junteros grumbled and a young Navarrese, disguised as a priest, assaulted Valiente in a Pamplona street.[95] His key ally against the internal opposition turned out to be the son of Don Javier, Carlos Hugo, who made a fulminant Príncipe de Asturias entry at the 1957 annual Carlist Montejurra amassment. The prince, greeted with exploding enthusiasm of the youth, delivered his La Proclama de Montejurra which, apart from social novelties, presaged modernization of the party and a more activist policy; it might have been interpreted as an offer to Franco.[96] However, this in turn triggered two secessions, which Valiente was not able to prevent; in 1957 so-called Estorilos declared Don Juan the legitimate Carlist heir,[97] and in 1958 the anti-Francoist intransigents created a splinter faction named RENACE.[98]

Valiente enjoyed full confidence of the claimant and in late 1960 his position within the organisation was enhanced; he was nominated Jefe Delegado, the position vacant since Fal's resignation in 1955.[99] However, his single-handed leadership was relatively brief. In early 1962 Carlos Hugo moved permanently from France to Madrid[100] and set up Secretaría Política, a team of his young collaborators, led by Ramón Massó.[101] Their cooperation with Valiente went well, even though the prince enforced restructuring of the party command layer and introduced new internal regulations; they shifted some power from jefe delegado to personal entourage of the prince.[102]

Initially the rapprochement with the regime, masterminded by Valiente and the Massó,[103] looked promising. The socially radical Falangist leaders, José Solís Ruiz and Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta, started to frequent Carlist rallies. During formation of the new Cortes in 1961 Franco followed Valiente's advice and nominated all the individuals suggested.[104] The regime permitted opening of Círculos Culturales Vázquez de Mella, a network of semi-official Carlist offices,[105] and authorized a few new Carlist periodicals;[106] some of them, like Montejurra,[107] gained popularity and became vehicles of mobilization especially among the youth.[108] Valiente had long audiences with Franco in 1961 and 1962; the dictator declared that he had not decided on his successor and the future monarch yet, and explicitly invited the Carlists to lobby for their cause. Carlos Hugo was personally admitted by Caudillo later in 1962.[109]

Leader: descent (1963-1968)

[edit]

Valiente, dubbed "the strong man of Carlism", in the early 1960s had to share more and more power with Don Carlos Hugo and his team.[110] Following setup of Secretaría Política in 1962, other new bodies mushroomed and diluted the powers of jefe delegado, with Masso and José Maria Zavala emerging as dynamic new leaders. The closest Valiente's collaborators, Jose Luis Zamanillo and Juan Sáenz-Díez, were getting increasingly marginalized. What started to amount to an open friction was not merely a personalist squabble; Zamanillo and Traditionalist theorists like Francisco Elias de Tejada were alarmed by ambiguous, socially-driven rhetoric of the carlohuguistas.[111] The conflict climaxed in 1963, when Zamanillo was expulsed,[112] Sáenz-Díez was demoted from treasury, while intellectuals related to the Siempre magazine, like Elias de Tejada and Rafael Gambra, distanced themselves from the organization.[113] Valiente, also somewhat uneasy about new ideas advanced by the prince, eventually consented to the measures adopted; he was guided by loyalty to the king.[114] However, the showdown left him increasingly isolated in the Carlist executive, now dominated by the progressist youth.[115]

In the mid-1960s it became clear that the strategy of posibilismo, which initially produced some results, was not leading any further. Censorship imposed almost total media blackout on the 1964 wedding of Don Carlos Hugo,[116] who was also denied the Spanish citizenship; no ministerial nominations materialized.[117] In 1965 Valiente was again admitted by Franco; during the conversation he realized that collaboration has reached its limits, that no more concessions could be expected and that the crowning of Don Carlos Hugo was not even a distant perspective.[118] Presence of prince Juan Carlos at the honorary tribune during the 1965 Victory Day parade made it clear that Franco was leaning towards the Alfonsist dynastical solution.[119]

The carlohuguistas also realized that the Valiente-sponsored posibilismo has crashed.[120] Their social radicalism was losing its pro-Falangist tone and was taking an increasingly Marxist turn instead. Valiente, isolated in the executive, was not in position to prevent it, especially that the new wave or reorganisation[121] left the party management in hands of Zavala and his team.[122] At the time, the carlohuguistas already controlled the Carlist student organization Agrupación Escolar Tradicionalista (AET) and the trade-unionist Movimiento Obrero Tradicionalista (MOT).[123] In 1966-1967 the Traditionalist old guard were effectively sidelined into decorative bodies.[124] Valiente was bombarded with alarm messages which denounced subversive revolutionary infiltration of Carlism; however, guided by loyalty to the king, which seemed to have endorsed the course advanced by his son, and judging the charges as exaggerated, he did not mount firm opposition.[125] Increasingly bewildered, isolated, in disagreement with the course promoted by the prince and consumed by tension, he tried to hand his resignation as jefe delegado; it was eventually accepted by Don Javier in late 1967[126] and made public in early 1968.[127]

Last years (1968-1982)

[edit]

Few weeks before getting his resignation accepted, in late 1967 Valiente was nominated to the Cortes, hand-picked by Franco from the pool of his personal appointees.[128] The exact mechanism of the nomination is not clear, though as master of his trademark balancing game the dictator might have intended to play Valiente against Don Carlos Hugo.[129] It is neither clear whether his resignation from jefatura delegada and his appointment to the Cortes were interrelated. Valiente accepted the nomination and in a letter to Don Javier he pledged to continue working for the Carlist cause.[130] In 1968-1969 his relations with the claimant remained cordial,[131] though impaired by health problems of both politicians.[132] It changed when in 1970 Valiente was re-appointed to the Cortes, again as Franco's personal appointee;[133] in an effusive acceptance letter Valiente thanked the dictator and declared that "estoy y quiero estar siempre con Vuestra Excelencia".[134] Don Javier demanded that the nominee declines the assignment. However, Valiente was already determined not to give in. In a personal letter to the claimant, dated November 1970, he underlined his loyalty to the Traditionalist principles, implicitly suggesting that it was Don Javier who might have abandoned them.[135] The two broke definitely in late 1970,[136] and in the spring of 1971 the so-called I Congreso del Pueblo Carlista, a grand carlohuguista assembly intended to turn Comunion Tradicionalista into a new Partido Carlista, formally expelled Valiente.[137] Later the related terrorist organisation Grupos de Acción Carlista planned an assault against him.[138]

In early 1971 Valiente was already engaged in buildup of Hermandad de Maestrazgo,[139] formally a combatant grouping but intended as a new, genuine Carlist organization.[140] He took part in a grand 1972 assembly, attended by some 700 participants,[141] though he did not assume any formal position; in 1973 he clashed with Zamanillo over would-be alliance with Blas Piñar.[142] Following relaxation of the law on political organizations, para-political groupings were no longer needed; Valiente started working around a new broadly based monarchist party, possibly with titular presidency of Juan Carlos.[143] The organization eventually materialized in 1975 as Unión Nacional Española, but following internal disagreements Valiente left it already in early 1976;[144] some doubted his credibility quoting the secret 1934 talks with Alfonso XIII.[145] Later this year he advocated sort of a Traditionalist umbrella organization in form of a confederation, but failed.[146] He voted in favor of Ley para la Reforma Política, dubbed "suicide of the Francoist Cortes";[147] as the chamber was dissolved Valiente lost his mandate in 1977. Also in 1977 he engaged in Alianza Popular, but abandoned it the following year in protest against endorsement of the 1978 constitution.[148] In 1979 he joined Derecha Democrática Española, a renewed and failed attempt to build a popular conservative party.[149]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ usually his year of birth is given as 1900, see e.g Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M service, available here. However, the official Cortes service claims he was born on November 18, 1903, compare his 1933 ticket discussed here

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M service, available here Archived 2021-04-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Movimiento Nobiliario 1938/2

- ^ Expediente académico de José Valiente Soriano, [in:] Archivo General Region de Murcía service, available here

- ^ Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Murcia 27.08.96, available here

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte service, available here

- ^ Movimiento Nobiliario 1938/2

- ^ Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, José María Valiente Soriano: Una semblanza política, [in:] Memoria y Civilización 2012 (15), p. 250

- ^ El Diario de Murcia 16.11.00, available here

- ^ in 1919 José Valiente still served as a notary in Valencia, El Debate 25.10.19, available here

- ^ La Libertad 23.08.21, available here

- ^ Enrique Lull Martí, Jesuitas y pedagogía: el Colegio San José en la Valencia de los años veinte, Madrid 1997, ISBN 9788489708167, p. 634

- ^ Las Provincias 05.06.16, available here

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ El Tiempo 20.01.28, available here

- ^ El Sol 25.05.33, available here

- ^ ABC 15.02.87, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Santander 11.12.74, available here, also Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Santander 26.05.75, available here

- ^ BOE 48 (1975), available here

- ^ BOE 37 (1993), available here

- ^ Revista Hidalguia 234 (1992), p. 613

- ^ BOE 37 (1993), available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 24.12.36, available here

- ^ in 1934 Valiente's sister got married in Onis José Ramón Prieto Noriega, La Epoca 14.09.34, available here

- ^ Alfredo Prieto Valiente entry, [in:] Oviedo Encyclopedia service, available here, also Prieto Valiente, Alfredo entry, [in:] Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte service, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia de Valencia 09.03.27, available here

- ^ BOE 35 (1953), available here

- ^ in the 1890s he was member of Comité republicano-progresista, El Pais 13.09.92, available here

- ^ La Voz 07.12.26, available here

- ^ and as the entry lecture delivered analysis of Italian fascism, El Debate 02.11.22, available here

- ^ José Ramón Montero, Entre la radicalización antidemocrática y el fascismo: las Juventudes de Acción Popular, [in:] Studia Historica 5 (1987), p. 49

- ^ Antonio Fontán, Los católicos en la universidad española actual, Madrid 1961, p. 42

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 251

- ^ José R. Montero, La CEDA: el catolicismo social y político en la II República, vol. 2, Madrid 1977, ISBN 9788474340297, p. 520

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 251

- ^ Joaquín Arrarás, Historia de la segunda República Española, Madrid 1964, p. 309

- ^ detailed discussion of JAP under Valiente's guidance and afterwards in Montero 1987, pp. 47-64

- ^ some scholars suggest that JAP was perhaps the most radical section of CEDA and it embraced certain vestiges of fascistoid culture, see Stanley G. Payne, Spain's First Democracy: The Second Republic, 1931-1936, Madison 1993, ISBN 9780299136741, p. 171. Other authors note that Valiente, though clearly anti-liberal, was hugely skeptical about fascism, and declared that “para nosotros ... el Estado ha de reconocer la familia, el municipio, la libertad de enseñanza, la libertad de prensa seriamente regulada, y, sobre todo, la libertad humana, entendida como la entiende nuestra teología y no al modo liberal”, quoted after Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 251

- ^ Julián Sanz Hoya, De la resistencia a la reacción: las derechas frente a la Segunda República (Cantabria, 1931-1936), Santander 2006, ISBN 9788481024203, p. 158

- ^ see his mandate at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 251

- ^ Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294, p. 131, Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 251

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, pp. 251-252

- ^ detailed discussion in Vázquez de Prada 2012, pp. 251-257

- ^ Historia contemporánea, Bilbao 1994, p. 87

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 199

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, pp. 199-200

- ^ Antonio M. Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República Española: Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054, p. 126

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 204

- ^ see his 1936 mandate at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ e.g. delivering lectures at local Ateneos, El Cantabrico 11.03.36, available here

- ^ Justo Gil Pecharroman, Sobre España inmortal, solo Dios. José María Albiñana y el partido nacionalista español (1930-1937), Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788436266627, p. 93

- ^ Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, p. 238

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 269

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 278

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 283, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 247

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 286

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, pp. 283-286

- ^ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 260

- ^ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 280

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, pp. 290-291

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, Fascism in Spain, Madison 2000, ISBN 9780299165642, p. 273

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 257

- ^ along Rodezno, Bilbao, Baleztena, Urraca, Fal, Oriol, Florida, Mazon, Arellano and Toledo, Blinkhorn 1975, p. 292

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, pp. 283-286

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 293

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 257

- ^ Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldía carlista. Memoria de una represión silenciada: Enfrentamientos, marginación y persecución durante la primera mitad del régimen franquista (1936-1955), Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711, pp. 95-97

- ^ El Adelanto 13.09.39, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 23.11.42, available here

- ^ see e.g. Diario de Burgos 04.12.45, available here

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ ”La resolución de la Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior e Investigación de 23 de noviembre de 1970, en la que se le declaró jubilado, lo identificaba como catedrático de Derecho Administrativo en situación de excedencia voluntaria. El 3 de diciembre de 1970 el Rector de la Universidad de Zaragoza devolvió las comunicaciones que había recibido sobre la jubilación porque de un catedrático de Derecho Administrativo con ese nombre “no se tienen antecedentes en este Rectorado”, Valiente Soriano, José María entry, [in:] Diccionario de Catedráticos Españoles de Derecho at UC3M

- ^ Miralles Climent 2018, p. 282

- ^ Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939-1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015, p. 61

- ^ Robert Vallverdú i Martí, La metamorfosi del carlisme català: del "Déu, Pàtria i Rei" a l'Assamblea de Catalunya (1936-1975), Barcelona 2014, ISBN 9788498837261, p. 96

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis UNED], Valencia 2009, p. 310

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 313

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 258. However, as late as in 1949 Valiente was denied a passport because of his 1945 Pamplona engagements, Miralles Climent 2018, p. 282

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 258

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 321

- ^ Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 106

- ^ Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 129

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 336

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 353

- ^ detailed discussion in Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El nuevo rumbo político del Carlismo hacia la colaboración con el regimen (1955-1956), [in:] Hispania LXIX/231, pp. 179–208

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 39

- ^ details of the forging of the collaborative course in Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El nuevo rumbo político del Carlismo hacia la colaboración con el regimen (1955-1956), [in:] Hispania LXIX/231 (2009), pp. 179–208

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, The Franco Regime, Madison 1987, ISBN 9780299110741, p. 455

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 60

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 57

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 61

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 75

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 116

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 150

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 150-152

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 158-167

- ^ Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 154

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 135

- ^ in 1961 there were 59 of them operational, Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 127

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 138

- ^ Montejurra paid due attention to Valiente as the party leader, but nothing more. He was pictured 22 times (most frequently in 1967 - 8 times and 1966 - 5 times), while photos of Carlos Hugo were published 220 times, photos of his wife Irene 194 times, and even photos of his mother Dona Madeleine were printed 40 times

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Madrid 2009, pp. 443-462

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 167

- ^ for organigram see Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo 1962-1977, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 8431315644, pp. 79-83

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 172-176, see Josep Maria Solé i Sabaté, Literatura, cultura i carlisme, Barcelona 1995, ISBN 9788478097920, p. 284

- ^ Javier Lavardín, Historia del ultimo pretendiente a la corona de España, Paris 1976, pp. 143-149

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 185-192

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 186

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 194-201

- ^ Lavardín 1976, p. 226

- ^ except Traditionalists who wholeheartedly embraced Francoism and were beyond Carlist organisation, like Antonio María Oriol Urquijo, in 1965 nominated the minister of justice

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 247-248

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 249

- ^ Lavardín 1976, pp. 273-279

- ^ organigram in Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 96

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 250

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, pp. 101-117

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 300

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 305-321

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2016, pp. 333-337

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 127. The position of Jefe Delegado was removed and replaced with a collective executive, Junta Suprema. Its president became Juan José Palomino Jiménez, and among its members one of the most notable figures was Ignacio Romero Osborne, Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 209

- ^ see his 1967 mandate at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ the author of the sole monograph of Valiente refrains from advancing any suggestions, Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 261

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, pp. 260-261

- ^ back in 1965 Don Javier conferred upon Valiente Order of Prohibited Legitimacy, Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965-1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015, p. 53

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 261

- ^ see his 1971 mandate at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 262

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, pp. 262-263

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 186

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, pp. 186-187, Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 263

- ^ Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 193

- ^ detailed discussion in Ramón Rodón Guinjoan, Una aproximación al estudio de la Hermandad Nacional Monárquica del Maestrazgo y del Partido Social Regionalista, [in:] Aportes 88 (2015), pp. 169-201

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 236

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 237

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 239

- ^ back in June 1972 he addressed the prince with the letter, in which he pointed to "coyuntura extraordinariamente favorable para atraer a la monarquía una sólida asistencia de profundo eco popular", Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 264

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 269

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 264

- ^ Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 280

- ^ Cortes Espanolas. Diario de Sesiones 29 (1976), p. 205, available here

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 265

- ^ Vázquez de Prada 2012, p. 265

Further reading

[edit]- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294

- Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo 1962-1977, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 8431315644

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis UNED], Valencia 2009

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957-1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, José María Valiente Soriano: Una semblanza política, [in:] Memoria y Civilización 15 (2012), pp. 249–265, ISSN 1139-0107

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El nuevo rumbo político del Carlismo hacia la colaboración con el regimen (1955-1956), [in:] Hispania LXIX/231 (2009), pp. 179–208, ISSN 0018-2141

External links

[edit]- 1900 births

- 1982 deaths

- Carlists

- Academic staff of the Complutense University of Madrid

- Leaders of political parties in Spain

- Members of the Congress of Deputies of the Second Spanish Republic

- Members of the Cortes Españolas

- People of the Spanish Civil War

- Popular Action (Spain) politicians

- Spanish monarchists

- Politicians from Valencia

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction)

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- University of Bologna alumni

- Academic staff of the University of Seville

- Academic staff of the University of Zaragoza

- 20th-century Spanish lawyers