Jonathan King

Jonathan King | |

|---|---|

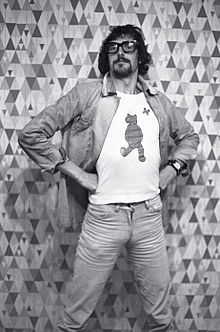

King in 2007 | |

| Born | Kenneth George King 6 December 1944[1] Marylebone, London, England |

| Education | Charterhouse School |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1965–2001 |

| Known for | Pop music, discovery of Genesis, early 10cc and Bay City Rollers hits, sex offences |

| Notable work | "Everyone's Gone to the Moon" (1965) and other singles |

| Television | Entertainment USA (BBC) |

| Awards | Music Industry Trusts Award, 1997[2] |

| Website | Kingofhits.com |

Jonathan King (born Kenneth George King; 6 December 1944) is an English singer, songwriter and record producer. He first came to prominence in 1965 when "Everyone's Gone to the Moon", a song that he wrote and sang while still an undergraduate, achieved chart success.[3] King's career in the music industry was effectively ended in 2001, when he was convicted of sexually abusing five teenage boys.

King discovered and named the rock band Genesis in 1967, producing their first album From Genesis to Revelation. He founded his own label UK Records in 1972. He released and produced songs for 10cc and the Bay City Rollers. In the 1970s King became known for hits that he performed and/or produced under different names, including "Johnny Reggae", "Loop di Love", "Sugar, Sugar", "Hooked on a Feeling", "Una Paloma Blanca" and "It Only Takes a Minute"; between September 1971 and 1972 he produced 6 top 30 singles in the UK.[4][failed verification]

In the 1980s King appeared on radio and television in the UK, including on the BBC's Top of the Pops and Entertainment USA. In 1990-91 he produced the Brit Awards and in 1997 he selected and produced the winning British entry for the Eurovision Song Contest, "Love Shine a Light" by Katrina and the Waves.[5]

In September 2001, King was convicted of child sexual abuse and sentenced to seven years in prison for having sexually assaulted five boys, aged 14 and 15, in the 1980s.[6] In November 2001, he was acquitted of 22 similar charges.[7] He was released on parole in March 2005.[8] A further trial for sexual offences against teenage boys resulted in several not guilty verdicts and the trial being abandoned in June 2018.[9][10]

Early life

[edit]Family background

[edit]

King was born in a nursing home in Bentinck Street, Marylebone, London, the first child of George Frederick John "Jimmy" King, managing director at Tootal, a tie manufacturer,[11] and his wife, Ailsa Linley Leon (1916–2007), a former actress.[12] Originally from New Jersey, Jimmy King had moved to England when he was 14. He attended Oundle School and Trinity College, Cambridge, before joining the American Field Service during World War II and later Tootal Ties and Shirts as managing director.[13]

King's birth was a forceps delivery and a muscle on his upper lip was affected during it, giving him his slightly crooked smile.[14][11] After he was born, the family lived in Gloucester Place, Marylebone, then moved to Surrey, where King and his younger brothers, James and Anthony, were raised in Brookhurst Grange, near Ewhurst.[14][15]

Stoke House and Charterhouse

[edit]King was sent to boarding school, first as a weekly boarder to pre-prep school in Hindhead, Surrey, then, when he was eight, to Stoke House Preparatory School in Seaford, East Sussex.[13] A year later, in 1954, after his father died from a heart attack, Brookhurst Grange was sold and the family moved to Cobbetts, a cottage in nearby Forest Green.[16]

Music became his passion around this time. King would save his pocket money for train trips to London to watch My Fair Lady, The King and I, Irma la Douce, Salad Days, Damn Yankees and Kismet from the cheap seats in the balcony. He also discovered pop music and bought his first single, Guy Mitchell's "Singing the Blues" (1956).[16][17]

In 1958, King became a boarder at Charterhouse in Godalming, Surrey. He wrote that he "loved Charterhouse immediately", with its history and "every possible area of encouragement from sport to intellectual pursuits." Unlike at Stoke House, there were other boys there who appreciated pop music. He bought a transistor radio and earphones and joined the "under the bedclothes" club, listening to Tony Hall, Jimmy Savile, Don Moss and Pete Murray on Radio Luxembourg, and keeping track of the New Musical Express charts.[17] The music, particularly Buddy Holly, Adam Faith, Roy Orbison and Gene Pitney, made him "ache with desire":

Since "It Doesn't Matter Anymore" swept me off my feet, I had become a raving pop addict, desperate for a fix every few seconds. I kept thick notebooks packed with copies of the weekly charts, adverts for new products, pages of predictions of future hits, reviews and comments about current artistes. Looking at them now, there was no way I could ever have avoided a future in the music industry.[17]

Gap year

[edit]King left Charterhouse in 1962 to attend Davies's, a London crammer, for his A levels. With his wages from a job stacking shelves in a supermarket, he made a demo of himself the following year singing "It Doesn't Matter Anymore" and "Fool's Paradise" Eden Kane song with the Ted Taylor Trio, a professional group in Rickmansworth.[18] Wearing a pinstripe suit and trainers, he approached John Schroeder of Oriole Records and told him he could make a hit record. "I have been studying the music industry for the last three years and it is one big joke," Schroeder reported him as saying. "Anyone can make it if they're clever and can fool a few people." After hearing King's demo, Schroeder booked a studio session with an orchestra but suspected that King could not sing in tune.[19]

King also joined a local band in Cranleigh, the Bumblies, as manager/producer and occasional singer, sometimes wearing thigh-length boots and long black gloves, during the band's appearances at birthday parties and similar.[18]

King failed the scholarship exam for Trinity College, Cambridge, but he was offered a place in 1963 after an interview.[18] He accepted, but first took a gap year and spent six months travelling with a round-the-world ticket from his mother. Staying mostly in youth hostels, he visited Greece, the Middle East, Asia, Australia and the United States, including Hawaii, where, in June 1964, he met the manager of the Beatles, Brian Epstein.[20][21][a] In October that year King began to study for his degree in English literature at Cambridge, lodging in Jesus Lane.[23]

Career

[edit]Early success

[edit]

Around the time King began at Cambridge, the Bumblies (featuring Terry Ward) recorded a song he had written and produced, "Gotta Tell", which King persuaded Fontana Records to release. It appeared in April 1965 and "rightly sank without trace", King writes, but the experience of taking it from label to label, and then trying to find people to play it, taught him how to promote a record. He called DJs and television producers to ask them to listen to it and, because it was Easter, delivered hundreds of vinyl singles to music critics complete with Easter eggs he had painted himself.[18] King and the Bumblies recorded another of his songs, "All You've Gotta Do", with producer Joe Meek, but nothing came of it.[20][24]

Keen to break into the music business, King contacted Tony Hall of Decca Records, who put him in touch with The Zombies' producers Ken Jones and Joe Roncoroni. King played them one of his songs, "Green is the Grass", and they asked him to write a B side. He offered them six songs, including "Everyone's Gone to the Moon", which became the A side. They also suggested he change his name.[23]

Decca released "Everyone's Gone to the Moon" in August 1965.[25] Relying on the contacts he had made while promoting "Gotta Tell", King plugged it relentlessly to radio stations to get it on their playlists. DJ Tony Windsor of Radio London, a pirate station broadcast from the MV Galaxy, was the first to play it, not only once, but three times in a row. (Windsor later said he did this only because of a problem with his other turntable.) It sold 26,000 copies the next day.[26]

When the song made number 18 in the charts, King was invited onto the BBC's Top of the Pops. The following day it sold 35,000 copies.[27] It peaked at number four in the UK (the Beatles were at number one with "Help!") and 17 in the US, and was awarded a gold disc.[25][28][29][30][31] Nina Simone, Bette Midler, and Marlene Dietrich all covered it. Dietrich sang "Everyone's Gone to the Moon" and its B side, "Summer's Coming", at the Golders Green Hippodrome in October 1966, with an arrangement by Burt Bacharach.[32][1] The single reached No. 17 in the US Billboard Hot 100[33][34] and was one of the songs carried on the Apollo 11 Moon mission.[35][36] In 2019, the track was included in the soundtrack of the Hollywood film In The Shadow of the Moon over the closing credits.[37]

His next release, "Green is the Grass", flopped, but the third (which he wrote and produced, but did not perform), "It's Good News Week" by Hedgehoppers Anonymous, was more successful. It was released in September 1965 through Decca and credited to King and his new publishing company, JonJo Music Co. Ltd, which was named after King, Ken Jones and Joe Roncoroni and based in Jones' and Roncoroni's office at 37 Soho Square.[38][39][40] Briefly banned by the BBC because of its lyrics about birth control, the song made the top five in the UK and top 50 in America.[3][41]

Also in 1965, King began contributing a column to Disc and Music Echo, a weekly magazine edited by Ray Coleman. King adopted a deliberately provocative style, promoting new acts but also publishing criticism of the music industry and particular artists.[42] Michael Wale described him as "the butterfly who stamped its foot".[43]

Discovery of Genesis

[edit]In early 1967, King attended an old boys' reunion at Charterhouse School. He said he went there to show off, "oust[ing] Baden-Powell as their most famous Old Boy."[44] When they heard he was going to be there, a school band recorded a demo tape for him, and a friend, John Alexander, left the cassette in King's car with a note, "These are Charterhouse boys. Have a listen".[45][46] Calling themselves Anon, the band consisted at that point of Peter Gabriel, Tony Banks, Anthony Phillips, Chris Stewart and Mike Rutherford, then all aged 15 to 17.[47][48]

King liked several songs such as "She is Beautiful" (which became "The Serpent" on the band's first album) and, according to Philips, they got the deal with King on the basis of that song. King signed the band to JonJo Music and licensed the short-term rights to Decca Records. He paid them £40 for four songs, and came up with their name, Genesis, to mark the start of his own career as a serious record producer.[46][47] According to Phillips, King was "hugely patient and indulgent" with the band.[46] John Silver, drummer on the first album, wrote in 2007:

We would be pretending to rehearse or simply waiting around and somehow somebody would bring a message to the flat, "Quick, get over to Jonathan King's flat, because Paul McCartney's turning up." We would scurry over as quickly as possible because the art was to be there, looking casual, before the next famous person arrived, so that Jonathan King could say, "Hey, these are my new protégés." I trusted him as a god, because he knew these people. It wasn't celebrity like it is now. There were only a few famous people and he knew them. If Jonathan said jump or stand backwards or stand on your head, basically you did it. This was the nature of the relationship; he was completely omnipotent, in a decent way.[49]

King produced their first three singles, including "The Silent Sun" (1968) and an album, From Genesis to Revelation (1969). Banks and Gabriel wrote "The Silent Sun" as a late-1960s Bee Gees "pastiche" to please King; Robin Gibb's voice was apparently King's favourite at the time.[50] The records made little impact; the album sold just 649 copies "and we knew all of those people personally," wrote Banks. King slowly lost interest in the band. Their next demo was even less "poppy"; the more complicated the songs, the less King liked them.[51] Genesis left King in 1970 for Tony Stratton Smith's Charisma Records, were joined by Phil Collins and Steve Hackett—and, after another two unsuccessful albums, released Foxtrot (1972) to critical acclaim.[52][53] King retained the rights to the first album and re-released it several times under different titles.[54] Rutherford said in 1985 that, "for all his faults", King had given the band an opportunity to record, which at that time was hard to come by.[b]

After graduating and broadcasting

[edit]King with Jimi Hendrix

1 January 1967

King at his graduation ceremony

23 June 1967

King on Top of the Pops

23 February 1972

King graduated from Cambridge in June 1967.[56] Shortly afterwards King started presenting Good Evening, a weekly television show that ran nationally on ATV at 6:30 pm on Saturdays from October 1967 to 1968.[57][58] The following year he began broadcasting for BBC Radio 1, including a "blast off" slot on the Stuart Henry show.[59]

Early 1970s

[edit]"It's Good News Week" (1965) was the last big hit King had for four years. Then his cover of "Let It All Hang Out" (1969) made the top 30 in January 1970, and he went on to become the top singles producer of 1971 and 1972,[60] beginning with "It's the Same Old Song". Released by B&C Records in December 1970 under a pseudonym, the Weathermen, it moved into the charts a month later. Using pseudonyms meant more airtime: radio producers might play several songs by the same artist during a programme without realizing they had devoted so much airtime to one person.[59]

King's 1971 releases included a version of Bob Dylan's "Baby, You've Been On My Mind", released as Nemo, which failed to chart; The Sun Has Got His Hat On, also as Nemo; "Sugar, Sugar" as Sakkarin; "Leap Up and Down (Wave Your Knickers in the Air)" by St Cecelia (this one a real band, rather than a pseudonym), which went to number 12; and "Lazybones", "Flirt" and "Hooked on a Feeling" – all released under his own name.[59]

Bell Records asked King to produce four songs for the Bay City Rollers, including their first hit, "Keep on Dancing", on which King sang the 13 backing vocals himself. Released in May 1971, the single reached number nine.[61]

"Hooked on a Feeling", a country song that King had turned into a pop hit, adding "ooga chaka ooga ooga" to the intro, was a Top Thirty hit. King's arrangement later gave Swedish group Blue Swede a US number one in April 1974.[62] The arrangement featured in Reservoir Dogs (1992), at least one episode of Ally McBeal, where it provided the music for the Dancing Baby (1998), and Guardians of the Galaxy (2014), although King writes that he made no money from the Blue Swede version.[63][64] Years later the track still garners coverage.[65]

Another top three 1971 hit was "Johnny Reggae", a ska pop song about a skinhead, written by King after he was introduced to a Johnny Reggae at the Walton Hop disco in Surrey.[59] It was sung by King and middle-aged session singers pretending to be teenagers, credited to The Piglets and released by Bell.[59][66] John Stratton writes that "Johnny Reggae" was the "first British hit with a ska beat to have been written by a white Englishman ... and performed by white English singers and musicians."[67][68] While, according to Lloyd Bradley, the BBC was reluctant to play reggae by black Jamaican artists, "Johnny Reggae", which Bradley described as "lamentable [and] audibly jarring", reached number three in the UK in November 1971 (when Slade's "Coz I Luv You" was number one) and stayed in the top 50 for 12 weeks.[69][c]

It has been reported that, under various different names and in assorted formats, he sold around 40 million records.[71]

UK records

[edit]

In 1972, King founded the UK Records label which was distributed by Decca and later PolyGram in the UK and London Records in the US. Chris Denning left Bell to run the UK office and Fred Ruppert, formerly of Elektra Records, the US office.[3][4][60] Don Wardell[72] then took over the US office, Denning left and Wardell moved back to run the UK company. King's brother Andy was hired in 1974 as the promotion manager.[73] Clive Selwood,[74] who had helmed John Peel's label Dandelion, then took over as manager.[75]

The label's first hit was "Seaside Shuffle" by Terry Dactyl and the Dinosaurs, followed by King's "Loop di Love", which reached number four, released under the pseudonym Shag.[76] Other signings included Ricky Wilde, then 11 years old and promoted to fill the gap later taken by Donny Osmond, a potential David Cassidy, Simon Turner,[77] Roy C, the First Class and Lobo. The label also released King's cover of "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" (1974) under the name Bubblerock, described as a "Grateful Dead"-style country version", which met with the approval of Mick Jagger.[3][78][79]

In June 1973, after seeing The Rocky Horror Show on its second night, King invested a 20% stake in it, making him one of its two original backers, along with Michael White, and produced and released The Rocky Horror Show Original London Cast.[80][11][81]

The label's most significant signing was 10cc. Eric Stewart, one of the band members, had known King since 1965, when Stewart was with The Mindbenders and King had wanted to manage them. The band had planned to release "Donna" as a B side, but decided it could be a hit: "We only knew of one person who was mad enough to release it," Stewart said, "and that was Jonathan King."[82][83] King gave the band its name and released two of the group's albums (10cc and Sheet Music) and eight singles. "Donna" (1972) and "Rubber Bullets" (1973), reached number two and one respectively, followed by "The Dean and I" (1973) and "The Wall Street Shuffle" (1974).[84] The band only dented the American market, with "Rubber Bullets" making 73 on the Billboard Hot 100.[85] 10cc left UK Records in 1975 for Mercury Records, after which they achieved success in America, particularly with "I'm Not in Love" (1975).[86]

Move to New York

[edit]

In April 1978, King stood for parliament as an independent in the Epsom and Ewell by-election, calling himself the Royalist party. He gained 2,350 votes.[87][88] A year later he decided to leave the music industry and closed UK Records.[78] He wrote to the charts committee of the British Phonographic Industry in August 1979 alleging that the lower levels of the charts reflected "clever promotion and marketing rather than good records", and suggesting that only information about the top 30 should be made available. The idea was that this would force programmers to base their airplay decisions on something other than the lower charts.[89]

The UK Records New York office on 57th Street was turned into an apartment, and King set about building a new career in writing and broadcasting. He was given a weekly five-minute slot on BBC Radio 1 called "A King in New York", a "Postcard from America" slot in Radio 4, and he reported for Radio 1 on the 1980 presidential election.[90] In December 1980, watching television in bed, he heard there had been a shooting outside the Dakota Apartments. He called and woke up BBC producer Tom Brook, who was living in New York; Brook became the first to announce to the UK that John Lennon had died.[91]

Throughout 1980 and 1981 King presented a radio talk show on New York's WMCA from 10–12 weekday mornings, and regularly reported from the United States on Top of the Pops. He devised and hosted a spinoff series, Entertainment USA, broadcast on BBC 2, which was nominated for a BAFTA in 1987.[92] He also created and produced No Limits, a youth programme.[93]

His first self-published novel, Bible Two, was published in 1982. It tells the story of a window dresser in "Selfishes" who inherits his family's millions. He was also hired by Kelvin MacKenzie, editor of The Sun, to write a weekly column, "Bizarre USA", which began in February 1985 and continued for eight years.[94] He continued with several music projects, including with the hard-rock supergroup Gogmagog, which released an EP, I Will Be There (1985).[95][96]

Brit Awards, Eurovision Song Contest

[edit]In 1987, King wrote and hosted the Brit Awards for the BBC,[97] and from 1990 to 1992 was the event's writer and producer. He resigned just after the 1992 show because he and the British Phonographic Industry, which runs the awards, disagreed about the show's format.[5][98][99] The following year he founded The Tip Sheet (1993–2002), a weekly trade magazine promoting new acts.[100]

Also in 1987, King accused the Pet Shop Boys of plagiarising the melody of Cat Stevens' song "Wild World" for their UK No. 1 single "It's a Sin". He made the claims in The Sun, for which he wrote a regular column during the 1980s. King also released his own cover version of "Wild World" as a single, using a similar musical arrangement to "It's a Sin", in an effort to demonstrate his claims. This single flopped, while the Pet Shop Boys sued King, eventually winning out-of-court damages, which they donated to charity.[101]

King's media work included finding and producing the Eurovision Song Contest entrant for the BBC in 1995. He selected several songs for them.[5] Love City Groove's song, "Love City Groove", came tenth in 1995. Gina G's "Ooh Aah... Just a Little Bit" came eighth the following year, and was number one on the UK chart.[102] "Love Shine a Light" by Katrina and the Waves came first in 1997.[103] His entry for 1998, when the UK hosted the event in Birmingham, was by Imaani and came second.[104] His writing continued. His second novel, The Booker Prize Winner, was published that year. He was involved in promoting the Baha Men's number one hit, "Who Let the Dogs Out?" (2000) which he first released under the name Fat Jakk and his Pack of Pets in 1998.[105][106]

In October 1997, King received a Music Industry Trusts Award.[2][107][108][109] The following year he devised The Record of the Year, produced by his Tip Sheet and London Weekend Television, a show in which the public voted for the year's best single.[110][111] In 2000 Nigel Lythgoe, executive producer of the new Popstars talent show, considered hiring King as anchor of its judging panel, but he turned it down. Lythgoe took the position himself.[112][113][114]

King reportedly turned down the chance to manage the KLF.[115]

Sexual offences

[edit]2001 trials

[edit]In September 2001, King was convicted, after a two-week trial at the Old Bailey, on four counts of indecent assault, one of buggery and one of attempted buggery, committed between 1983 and 1987 against five boys aged 14 and 15. In a second trial, he was found not guilty after an alleged victim (someone King denied having ever met) acknowledged that he could have been 16 or older at the time. Three further trials that had been scheduled were ordered abandoned.[d][117][71][118] King claimed, among other things, that the lack of a statute of limitations in the UK for sex offences meant he had been unable to defend himself adequately because of the many years that had passed.[119]

The National Criminal Intelligence Service had begun investigating King for child sexual abuse in 2000, when a man told them he had been assaulted by King and others 30 years earlier.[120] The man had originally approached publicist Max Clifford, himself later jailed in 2014 for sexual assault; Clifford told him that he should go to the police.[121] King was arrested in November 2000 and bailed on £150,000, £50,000 of which was put up by Simon Cowell.[122] He was arrested again in January 2001 on further allegations.[123][124] 27 men told police that King had sexually assaulted them during the period 1969–1989.[125] Police found pictures of teenagers in a search of King's home.[125] King admitted having approached thousands of people with questionnaires about youth interests, doing market research. The questionnaires asked recipients to list topics according to importance including music, sport, friends and family; the prosecution claimed that boys who listed sex high in their list of priorities were then targeted by King.[126]

After the second trial at the Old Bailey on 21 November 2001, Judge David Paget QC sentenced King to seven years in prison using the first trial verdict as a sample for "all previous sexual behaviour". In addition, King was placed on the Sex Offenders Register, prohibited from working with children, and ordered to pay £14,000 costs.[119][e] In 2003, the Court of Appeal rejected his application to appeal both the conviction and the sentence; he had argued that the conviction was unsafe and the sentence, with guidelines of two years, had been "manifestly too severe".[128] He appealed twice unsuccessfully to the Criminal Cases Review Commission,[129][130] and was released on parole in March 2005.[131]

King has complained about his media coverage since his 2001 conviction. In 2005, he went to the Press Complaints Commission about an article in the News of the World that said he had gone to a park to "ogle" boys. In fact he had gone there at the request of a documentary maker. The complaint was not upheld, but Roy Greenslade argued that King had a good case.[132] In October 2011, then-BBC Director-General Mark Thompson apologised to King for the removal of King's performance of "It Only Takes a Minute" from a repeat, on BBC Four, of a 1976 episode of Top of the Pops. King described the cut as a "Stalinist revision approach to history".[133] When asked by a newspaper in 2012 if he believed he had anything to apologise for, to anybody from his past, King replied, "The only apology I have is to say that I was good at seduction. I was good at making myself seem attractive when I wasn't very attractive at all".[7] He appeared in front of the Leveson Inquiry.[134]

After prison

[edit]Journalist Robert Chalmers wrote that King's creative output after he left prison "resembled a primal scream of rage".[11][1] Two self-published novels appeared: Beware the Monkey Man (2010), under the pen name Rex Kenny, and Death Flies, Missing Girls and Brigitte Bardot (2013), under his real name, Kenneth George King. He also published a diary, Three Months (2012), and two volumes of his autobiography, Jonathan King 65: My Life So Far (2009) and 70 FFFY (2014). King maintained an interest in prison issues and writes a column for Inside Time, the national newspaper for prisoners.[135]

He released Earth to King in 2008. One of the new songs on the album, "The True Story of Harold Shipman" was about the serial killer Dr. Harold Shipman, in which King suggested that Shipman may have been a victim of the media.[136] He also self-produced three films. Vile Pervert: The Musical (2008), available for free download, is a 96-minute film in which King plays all 21 parts and presents his version of events surrounding his prosecution. He portrays his viewpoint of the events responsible for his troubles.[137] In one scene King, dressed as Oscar Wilde, sings that there is "nothing wrong with buggering boys".[137] Rod Liddle in The Spectator called it "a fantastically berserk, bravado performance".[138] Me Me Me (2011) was described by King as "a re-telling of Romeo and Juliet".[139] The Pink Marble Egg (2013) is a spy story; for publicity King drove down the Promenade de la Croisette in Cannes with a pink papier-mâché egg on top of his Rolls-Royce during the Cannes Film Festival.[140]

2018 trial

[edit]In August 2015, King wrote an article for The Spectator magazine concerning Sir Edward Heath, the subject of the now-discredited Operation Midland.[141] In September that year, King was arrested as part of Operation Ravine, a further investigation into claims of sexual abuse at the Walton Hop disco in the 1970s.[142] He was later released on bail.[143][144] On 25 May 2017, he was charged by Surrey Police with 18 sexual offences, relating to nine boys aged between 14 and 16, allegedly carried out between 1970 and 1986. He was released on bail and appeared at Westminster Magistrates' Court on 26 June,[145] where he was released on conditional bail to appear at Southwark Crown Court on 31 July.[146][147] His trial began on 11 June 2018; on 27 June, he was declared not guilty on several charges, and the jury was discharged.[148][149]

On 6 August 2018, Judge Deborah Taylor, saying that Surrey Police had made "numerous, repeated and compounded" errors during the investigation, described the situation as a "debacle". In her ruling she said "I have concluded that this is a case where even if it were possible to have a fair trial, it is in the rare category where the balance, taking account of the history, the failures and misleading of the Court, is in favour of a stay on the basis that following what has occurred, continuation would undermine public confidence in the administration of justice". Taylor said that the case against King had been motivated by "concerns about reputational damage to Surrey Police" following the allegations of sexual abuse against Jimmy Savile.[150] Surrey Police "wholeheartedly apologised" to King, saying: "We deeply regret that despite these efforts we did not meet the required standards to ensure a fair trial."[9] King refused to accept the apology, and criticised Surrey Police for "deep, institutional faults".[151][10] He urged both the Chief Constable and the Police and Crime Commissioner to go.[152][153][154]

In August 2019, Chief Constable Stephens, who had replaced Ephgrave, announced that, in the year since King's acquittal, the Surrey Police success rate for convictions in sex abuse cases had dropped from 20% to "under 4%".[155] On 22 November 2019, an independent review into the police investigation leading to the trial was published. It was critical of the handling of disclosure of documents to King's defence prior to the trial, and questioned whether some of the staff involved had been qualified or experienced enough to handle the case.[156][157]

Selected works

[edit]Discography

[edit]Books

[edit]- (1982) Bible Two: A Novel According to Jonathan King, London: W. H. Allen/Virgin Books.

- (1997) The Booker Prize Winner, London: Blake Publishing.

- (2009) 65: My Life So Far, London: Revvolution Publishing Ltd.

- (2010) Beware the Monkey Man (as Rex Kenny), London: Revvolution Publishing Ltd.

- (2012) Three Months: 100 Glorious Sunny Days in the Summer of 2012. A Diary, London: Kingofhits.com.

- (2013) Death Flies, Missing Girls and Brigitte Bardot (as Kenneth George King), Amazon Media.

- (2014) 70 FFFY, London: Revvolution Publishing Ltd, Amazon Media.

- (2016) The Spirit Phone (as Kate Genifer), London: Revvolution Publishing Ltd, Amazon Media.

- (2018) Don't Go In (as KG Jonathan King), London: Revvolution Publishing Ltd, Amazon Media.

- (2019) Guilty, London: Revvolution Publishing Ltd, Amazon Media.

Films

[edit]- (2008) Vile Pervert: The Musical

- (2011) Me Me Me

- (2013) The Pink Marble Egg

- (2019) Guilty

- (2022) The Great ReSet - It's Good News Week

Notes

[edit]- ^ For June 1964: King flew to Hawaii a week after booking himself into the Southern Cross Hotel in Melbourne, where the Beatles were staying. The Beatles were there for four days from 14 June 1964.[22]

- ^ Mike Rutherford, 1985: "Jonathan King, for all his faults – he has a funny reputation in England – did give us a fantastic opportunity. Because in those days, in England, you couldn't get in the studio. I mean, now a new group can very easily get a chance to go and record a single, just something, you know, to show there's something going for them. In those days, to get any sort of record contract, was really magical. And he gave us a chance to do a whole record. You've got a bunch of musicians who were really amateur, could barely play well, were barely a group, and were able to go in one summer holiday and make a record."[55]

- ^ A Jamaican version of "Johnny Reggae", "Heavy Reggae (Johnny Reggae)", was released in 1974 by the Roosevelt Singers.[70]

- ^ At the time of the alleged offences, the applicable legislation was the Sexual Offences Act 1967. This decriminalized private consensual homosexual acts between parties aged 21 and over. If the sex was consensual and the alleged victim was 16 or over, the statute of limitations was 12 months.[116]

- ^ King served his sentence in Belmarsh, Elmley and Maidstone prisons.[127]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Walker, Tim (28 November 2011). "Jonathan King: 'My book's an online hit, millions click on my videos. How about lifting the media ban on me?'". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Previous award recipients", Music Industry Trusts Award, 16 March 2015

- ^ a b c d Eder, Bruce. "Jonathan King". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ a b "King Forms U.K. Records," Billboard, 9 September 1972, 32.

- ^ a b c "The music industry's outsider", BBC News, 24 November 2000. Note: the BBC says that King resigned from the Brit Awards in 1991, but this appears to be an error.

- ^ "Jonathan King jailed for child sex abuse". The Guardian. London. 21 November 2001.

- ^ a b "Jonathan King: 'The only apology I have is to say that I was good at seduction'". The Independent. 21 April 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "Jonathan King freed from prison", BBC News, 29 March 2005.

- ^ a b Ward, Victoria (6 August 2018). "Surrey Police apologise after judgment reveals disclosure failings in Jonathan King sex abuse case". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ a b Finkelstein, Daniel (15 August 2018). "Trials of Jonathan King should worry us all". The Times. London. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d Chalmers, Robert (22 April 2012). "Jonathan King: 'The only apology I have is to say that I was good at seduction'". The Independent on Sunday.

- ^ "Ailsa Linley", Kingofhits.co.uk; King, Jonathan (2009). 65 My Life So Far, London: Revvolution Publishing Ltd., chs. 1, 25.

- ^ a b King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 2.

- ^ a b King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 1.

- ^ King, Jonathan. "Brookhurst Grange Ewhurst Surrey". Kingofhits.co.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 3.

- ^ a b c King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 4.

- ^ a b c d King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 6.

- ^ Schroeder, John (2016). All for the Love of Music, Matador, 66–68.

- ^ a b King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 7.

- ^ "The rise and fall of a pop tsar". Press Association. 29 March 2005.

- ^ Cahill, Mikey (18 June 2014). "Photo essay: A look back at how the Beatles rocked Melbourne and their teenage fans went wild", Herald Sun.

- ^ a b King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 8.

- ^ "The Joe Meek Story", 8 February 1991, YouTube @ 00:08:02.

- ^ a b Lazell, Barry (1989). Rock movers & shakers, Billboard Publications, 279.

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 9.

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 9; "Everyone's Gone to the Moon", Top of the Pops, BBC, 1965.

- ^ For number three, Melody Maker, 21 August 1965, cited in King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 9.

- ^ Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins. 192. ISBN 978-0-214-20512-5.

- ^ Warwick, Neil; Kutner, Jon; Brown, Tony (2004). The Complete Book of the British charts: Singles & Albums. Omnibus Press, 602.

- ^ Nite, Norm N. (1978). Rock on. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock N' Roll: The Solid Gold Years. Ty Crowell Co, 262.

- ^ "Marlene Dietrich sings "Everyone's Gone to the Moon" (Live, 1966)", YouTube.

- ^ Brent Mann (2003), "99 Red Balloons...and 100 Other All-Time Great One-Hit Wonders", Books.google.co.uk, p. 43, ISBN 9780806525167, retrieved 28 November 2015

- ^ "The rise and fall of a pop tsar". The Guardian. London. Press Association. 29 March 2005.

- ^ Guerrieri, Matthew (3 July 2019). "A journey to the moon, by a master of the theremin". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Obituary: Michael Collins, astronaut who was part of Apollo 11 mission that saw Man walk on the moon". HeraldScotland. 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Music from In the Shadow of the Moon". Tunefind.

- ^ File:Its Good News Week.jpg, image courtesy of Wikipedia

- ^ "JonJo Music Ltd", Discogs. Retrieved 31 July 2016

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 11.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums. Guinness World Records. 249. ISBN 978-1-904994-10-7.

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 10.

- ^ Vale, Michael (1972). VoxPop, Larousse Harrap Publishers, 78.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2004). Turn It On Again, Hal Leonard Corporation, 11.

- ^ Rutherford, Mike (2014). The Living Years, Constable, 45.

- ^ a b c Banks, Tony, et al. (2007). "Charterhouse (1963–1968)," in Philip Dodd (ed.), Genesis: Chapter and Verse, St. Martin's Griffin, 27–28.

- ^ a b Welch, Chris (1995). The Complete Guide to the Music of Genesis. Omnibus Press, 1–3.

- ^ "Jonathan King to appear in BBC Genesis documentary". BBC News. 26 September 2014.

- ^ Banks, et al. (2007), "Christmas Cottage (1968–1970)", 57.

- ^ Banks 2007, 29.

- ^ Banks 2007, 52.

- ^ White, Timothy (1986). "Gabriel," Spin magazine (50–63),54.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Genesis". AllMusic. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Hombach, Jean-Pierre (2012). Phil Collins. 17. ISBN 978-1470134440.

- ^ Mike Rutherford interviewed by Dan Neer (1985). Mike on Mike (Vinyl, 12" Promo interview recording). Atlantic Recording Corporation. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ "Jonathan King becomes M.A. (Cantab.)", Londoner's Diary, London Evening Standard, 23 June 1967.

- ^ Billboard, 14 October 1967, 64; for ATV, London Magazine, 7, 1967, 59.

- ^ For 1968, Wale, Michael (1972). Voxpop: Profiles of the Pop Process, Larousse Harrap Publishers, 85.

- ^ a b c d e King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 12.

- ^ a b "UK Producer King Launches Own Label", Billboard, 27 May 1972, 51.

- ^ Coy, Wayne (2005). Bay City Babylon: The Unbelievable But True Story of the Bay City Rollers. IGS Entertainment. 23–27. ISBN 978-1587364631.

- ^ Bronson, Fred (2003). The Billboard Book of Number One Hits, Billboard Books, 361.

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 12; King, FFFY, 13.

- ^ Torstar, Staff (22 August 2014). "Heard in Guardians of the Galaxy: What's with 'ooga chaka'?". Metronews.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Hooked on the Ooga Chagga: Sweden's First Hot 100 No. 1 Was Unleashed 45 Years Ago Today". Billboard.

- ^ "Record Details", www.45cat.com.

- ^ Stratton, John (2016). "The Travels of Johnny Reggae: From Jonathan King to Prince Far I

- ^ From Skinhead to Rasta," When Music Migrates: Crossing British and European Racial Faultlines, 1945–2010. Routledge (59–79), 59–60.

- ^ Stratton 2016, 59–60; Bradley, Lloyd (2001). Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King. Penguin, 256 (also published as This is Reggae Music).

- ^ Stratton 2016, 60.

- ^ a b Ronson, Jon (1 December 2001). "The fall of a pop impresario". The Guardian

- ^ "Don Wardell". 1073modfm.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "International Turntable," Billboard, 22 June 1974, 52.

- ^ "UK". 7tt77.co.uk.

- ^ All the Moves (but None of the Licks): Secrets of the Record Business: Amazon.co.uk: Clive Selwood: 9780720611533: Books. Amazon.co.uk. ASIN 0720611539.

- ^ "Shag", 45cat.com. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Partridge, Rob (23 December 1972). "New Pop Audience Emerging in U.K.", Billboard, 10.

- ^ a b Southall, Brian (2003). The A-Z of record labels. Sanctuary. 276. ISBN 978-1860744921.

- ^ "Jonathan King – Satisfaction", YouTube.

- ^ "The Rocky Horror Show Original London Cast". Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2016). The Rocky Horror Picture Show FAQ, Hal Leonard Corporation.

- ^ Tremlett, George (1976). The 10cc Story Futura.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2012). The Cost of Living in Dreams: The 10cc Story, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, p. 61–62.

- ^ Davis, Sharon (2012). Every Chart Topper Tells a Story: The Seventies, Random House.

- ^ "10cc – Chart history". Billboard. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "10cc". AllMusic. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ "1978 By Election Results", by-elections.co.uk

- ^ Arkell, Harriet (21 November 2001). "Relentless ego of self-styled man". London Evening Standard.

- ^ "King Advocates Chart Cuts," Billboard, 25 August 1979, 68.

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 15.

- ^ Brooks, Tom (8 December 2010). "Lennon's death: I was there", BBC News.

- ^ "Television. Light Entertainment Programme in 1987", BAFTA and peaked with 9.7 million viewers.

- ^ Yockel, Michael (30 July 2002). "Jonathan King, Queen of Pop", New York Press.

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 16.

- ^ Munro, Eden (25 March 2009). "Gogmagog", Vue.

- ^ "Who is Jonathan King?". The Guardian. 24 November 2000.

- ^ "Brit Awards 1987". Brits.co.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Lister, David (17 January 1997). "Jonathan King calls for boycott of Brit awards". The Independent. London.

- ^ King, 65 My Life So Far, ch. 17.

- ^ "King's Tip Sheet to carry on". BBC News. 21 November 2001.

- ^ Street-Porter, Janet (2 April 2005). "Editor-At-Large: He lured boys. He's a bully. Now he bleats". The Independent. London.

- ^ "About Gina G". eurovision.tv. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Why Eurovision needs to be saved from the BBC". The Spectator. 18 May 2013.

- ^ Saunders, Tristram Fane (2 May 2018). "Eurovision: every single UK entry ranked, from worst to best". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Richard Rushfield (18 January 2011). American Idol: The Untold Story. Hachette Books. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-4013-9652-7.

- ^ Amter, Charlie (10 March 2019). "'Who Let the Dogs Out?' Doc Offers Fascinating Look at the Origin of the Baha Men Hit". Variety.

- ^ "Newsline," Billboard, 15 November 1997, 50

- ^ "MIT Award 1997 Jonathan King", JME Photo Library. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ McGee, Alan (23 January 2007). "Should the BPI dethrone Jonathan King?", The Guardian.

- ^ Young, Graham (19 December 1998). "I'm the Greatest!; (Says Jonathan King)", Birmingham Evening Mail.

- ^ Sexton, Paul (25 December 1999). "U.K. TV Awards Show Boosts Sales," Billboard, 5, 81.

- ^ Nolan, David (2010). Simon Cowell – The Man Who Changed the World, John Blake Publishing, 61.

- ^ Rushfield, Richard (2011). American Idol: The Untold Story, Hachette Books, 15–16; Rushfield, Richard (15 January 2011)

- ^ "The Battle for 'American Idol'", Newsweek

- ^ The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (2017). 2023. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-33808-5.

- ^ Sexual Offences Act 1967, legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "Jonathan King jailed for child sex abuse". The Guardian. London. 21 November 2001.

- ^ Ronson, Jon (2006). "The Fall of a Pop Impresario," Out of the Ordinary True Tales of Everyday Craziness, Picador, 192–240.

- ^ a b Clough, Sue; O'Neill, Sean (22 November 2001). "Pop veteran Jonathan King given seven years for abusing schoolboys". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Hall, Sarah (22 November 2001). "Victim's angry email led to downfall". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Norman, Matthew (4 May 2014). "Max Clifford played a crucial role in the conviction of Jonathan King. Now the roles have been reversed", The Independent. London.

- ^ Walker, Tim (27 November 2011). "Jonathan King: 'My book's an online hit, millions click on my videos. How about lifting the media ban on me?'", The Independent.

- ^ "Second arrest for Jonathan King", The Guardian, 24 January 2001.

- ^ "King faces fresh charges". BBC News. 25 January 2001.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Sean (22 November 2001). "The shameful private life hidden behind flamboyant self-publicity". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "King's path to shame". BBC News. 21 November 2001.

- ^ King, Jonathan (13 June 2004). "What's on your prison tray? – Jonathan King", The Guardian.

- ^ "King loses appeal bid". BBC News. 24 January 2003.

- ^ Tryhorn, Chris (15 April 2003). "King makes fresh appeal bid", The Guardian

- ^ "King abuse case 'to be reviewed". BBC News. 29 January 2006.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (29 March 2005). "Jonathan King: 'I have had a brilliant time'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

What remains is that I am absolutely 100 per cent innocent of the crimes and my lawyer tells me he will quash my conviction by appeal. But I am not that important

- ^ Greenslade, Roy (4 July 2005). "King had cause for complaint", The Guardian.

- ^ "BBC apology to Jonathan King after he is cut from repeat". The Daily Telegraph. 19 October 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (25 January 2012). "Leveson inquiry: Jonathan King claims his was miscarriage of justice victim". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Jonathan King", Inside Time.

- ^ "Families' anger over Shipman song", BBC News, 12 July 2007.

- ^ a b Moore, Matthew (15 May 2008). "Jonathan King makes Vile Pervert: The Musical". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Liddle, Rod (22 October 2011). "The King strikes back". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014.

- ^ Sharp, Rob (12 May 2011). "Cannes Diary: From disgraced D-listers to ex-drug dealing singers, festival embraces them all", The Independent.

- ^ Wells, Dominic (20 May 2013). "Cannes Film Festival 2013: Marilyn Monroe, Lesbian Weddings, Nuns of the Future and Occupy Movement". International Business Times UK.

- ^ "Why I don't believe that Ted Heath was gay". Blogs.spectator.co.uk. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Jonathan King arrested in child sex offences probe". BBC News. 10 September 2015.

- ^ "Jonathan King freed on bail over sex offence claims". BBC News. 10 September 2015.

- ^ "Ex-DJ Denning charged with child sex offences". BBC News. 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Music mogul Jonathan King charged with historical sex offences". BBC News. 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Music mogul Jonathan King in court over sex crimes". BBC News. 26 June 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Ex-DJ Jonathan King gives thumbs up after appearing in court on child sex charges". The Daily Telegraph. London. 26 June 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Wylie, Catherine (31 July 2017). "Ex music mogul Jonathan King appears in court over Walton Hop child sex abuse claims". GetSurrey. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Music mogul Jonathan King sex trial jurors discharged". BBC News. 27 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ McKeon, Christopher (30 August 2018). "Surrey Police failures in Jonathan King child sex abuse investigation 'undermined criminal justice system'". SurreyLive. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ "Music mogul Jonathan King slams police apology". BBC News. 10 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ "Former DJ King calls for Munro to step down". Farnham Herald. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ McKeon, Christopher (13 December 2018). "Chief Constable Nick Ephgrave to leave Surrey Police for Met". getsurrey.

- ^ "Munro loses crime commissioner vote". Farnham Herald.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Backlog of child sex offences 'significant'". BBC News. 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Jonathan King child abuse trial: Surrey Police criticised over collapse". BBC News. 22 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Operation Ravine Peer Review Report Surrey Police, 22 November 2019.

External links

[edit]- 1944 births

- Living people

- 20th-century English criminals

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- BBC television presenters

- English male criminals

- English people convicted of indecent assault

- Child sexual abuse in England

- Criminals from London

- Decca Records artists

- English people convicted of child sexual abuse

- English people of American descent

- English pop singers

- English record producers

- English television presenters

- Genesis (band)

- British impresarios

- English LGBTQ singers

- Parrot Records artists

- People educated at Charterhouse School

- Prisoners and detainees of England and Wales

- English male singer-songwriters

- The Sun (United Kingdom) people