John Salathé

John Salathé | |

|---|---|

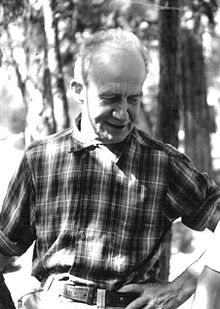

John Salathé at Camp 4 in Yosemite Valley in 1964. | |

| Born | June 14, 1899 |

| Died | August 31, 1992 |

| Occupation(s) | Blacksmith, rock climber |

John Salathé (June 14, 1899 – 31 August 1992)[1] was a Swiss-born American pioneering rock climber (and particularly in big wall climbing and in aid climbing), blacksmith, and the inventor of the modern steel piton.[2] In his later years he promoted Christian spiritualism and vegetarianism.[2]

Biography

[edit]John Salathé, also known as Jean Salathé, was born on June 14, 1899, in Switzerland in the village of Niederschöntal, near Basel.[1] He was one of six children. In his hometown, he was an apprentice blacksmith before moving to Paris first, and then Le Havre where he enrolled as a merchant seaman for 4 years, traveling as far as Africa and Brazil.[1] In 1925, Salathé left Bordeaux, in France and travelled to Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada before travelling to Montreal where he met his wife, Ida Schenk. In March 1930, at the age of 30, Salathé, together with his wife and child, emigrated from Montreal, Canada to finally settle in San Mateo, United States. In 1932, he founded Peninsula Wrought Iron Works, a one-man blacksmith company.[2]

In 1945, Salathé had a mystical experience and became a strict vegetarian.[2][3][4] He became a member of the American Alpine Club in 1950 and was elected to Honorary Membership in 1976.[1]

Lost Arrow pitons

[edit]When he began climbing in 1945, he found that traditional pitons used for climbing in the Alps were too soft to be driven into narrow cracks without buckling. In his San Mateo business, Peninsula Wrought Iron Works,[1] Salathé used high-carbon chrome-vanadium steel, similar to that used to make Ford axles, to forge extremely strong pitons which could be hammered into the hard Yosemite granite without buckling, as well as removed without getting mangled, thus rendering them reusable. These thin pitons became known as Lost Arrows, and are still manufactured under that name by Black Diamond Equipment.

Ascents

[edit]In 1946, Salathé and Anton (Ax) Nelson climbed the southwest face of Half Dome. The two climbers spent the night on a small ledge, making it Yosemite's first climbing route to require a bivouac.[5]

In September, 1947, Salathé and Nelson managed the first "ground-up" ascent of the Lost Arrow Spire in Yosemite, by the Lost Arrow Chimney route. The Lost Arrow piton was named after the spire. The ascent took five days and included four bivouacs. The first ascent of the spire summit was achieved in 1946 by Anton Nelson and friends, who threw a rope over the summit beforehand to aid in their climb.[5][6]

In July, 1950, Allen Steck and Salathé made the first ascent of the 1,500 foot (500 m) north face of Sentinel Rock. This five-day ascent was considered the last of the great Yosemite problems of the day.[5] Their route, the Steck-Salathé Route is now a classic rock climb.

Later life

[edit]In 1953, Salathé suffered a mental breakdown, abandoned his family, and returned to Switzerland to live in a hut above Lake Maggiore.[2] He became a devoted member of a Christian spiritualist religious group called the Spiritual Lodge Zurich, led by the medium Beatrice Brunner.[2] He climbed the Matterhorn in August, 1958, his last significant mountaineering achievement. In 1963, he returned to the United States and spent 20 years car camping and wandering through the deserts and mountains of California.[2] He maintained his vegetarian diet based largely on wild grasses and herbs, that he sought out, with barley, pinto beans and rice and preached his spiritualist beliefs.[2]

Death and legacy

[edit]Salathé died on August 31, 1992, in Southern California.[2]

The Salathé Wall on El Capitan was named to honor Salathé (although he did not climb it) around 1960 by Royal Robbins.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Allen Steck, Robin Hansen (1994). "In Memoriam: John Salathé" (PDF). American Alpine Journal. 36 (68): 321–322.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roper, Steve (1994). Camp 4: Recollections of a Yosemite Rockclimber. Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers. pp. 31–49. ISBN 0-89886-587-5.

- ^ Arce, Gary. (1996). Defying Gravity: High Adventure on Yosemite's Walls. Wilderness Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0899971858

- ^ "The fascinating history behind America’s most famous climbing spot". telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Jones, Chris (1976). Climbing in North America. Berkeley, California, USA: American Alpine Club / University of California Press. pp. 185–194. ISBN 0-520-02976-3.

- ^ Challacombe, J. R. (June 1954). "The Fabulous Sierra Nevada". The National Geographic Magazine. Vol. CV, no. Six. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. pp. 826–830.