Doc Holliday

Doc Holliday | |

|---|---|

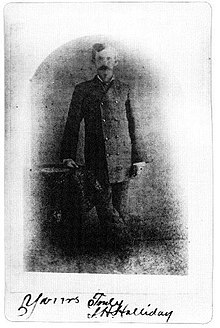

Autographed portrait, Prescott, Arizona, c. 1879 | |

| Born | John Henry Holliday August 14, 1851 Griffin, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | November 8, 1887 (aged 36) |

| Resting place | Pioneer Cemetery (a.k.a. Linwood Cemetery), Glenwood Springs, Colorado, U.S. 39°32′22″N 107°19′9″W / 39.53944°N 107.31917°W |

| Education | Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery |

| Occupation(s) | dentist, professional gambler, gunfighter |

| Known for | Gunfight at the O.K. Corral Earp Vendetta Ride |

| Spouse | |

| O.K. Corral gunfight |

|---|

| Principal events |

| Lawmen |

| Outlaw Cowboys |

John Henry Holliday (August 14, 1851[citation needed] – November 8, 1887), better known as Doc Holliday, was an American dentist, gambler, and gunfighter who was a close friend and associate of lawman Wyatt Earp. Holliday is best known for his role in the events surrounding and his participation in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona. He developed a reputation as having killed more than a dozen men in various altercations, but modern researchers have concluded that, contrary to popular myth-making, Holliday killed only one to three men. Holliday's colorful life and character have been depicted in many books and portrayed by well-known actors in numerous movies and television series.[1]: 415

At age 20, Holliday earned a degree in dentistry from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery. He set up practice in Griffin, Georgia, but he was soon diagnosed with tuberculosis, the same disease that had claimed his mother when he was 15 and his sister before his birth, having acquired it while tending to his mother's needs. Hoping the climate in the American Southwest would ease his symptoms, he moved to that region and became a gambler, a reputable profession in Arizona in that day.[2] Over the next few years, he reportedly had several confrontations. He saved Wyatt Earp's life during a saloon confrontation in Texas, and they became friends. In 1879, he joined Earp in Las Vegas, New Mexico, and then rode with him to Prescott, Arizona,[3] and then Tombstone. While in Tombstone, local members of the outlaw Cochise County Cowboys repeatedly threatened him and spread rumors that he had robbed a stagecoach. On October 26, 1881, Holliday was deputized by Tombstone city marshal Virgil Earp. The lawmen attempted to disarm five members of the Cowboys near the O.K. Corral on the west side of town, which resulted in the famous shootout.

Following the Tombstone shootout, Virgil Earp was maimed by hidden assailants while Morgan Earp was killed. Unable to obtain justice in the courts, Wyatt Earp took matters into his own hands. As the recently appointed deputy U.S. marshal, Earp formally deputized Holliday, among others. As a federal posse, they pursued the outlaw Cowboys they believed were responsible. They found Frank Stilwell lying in wait as Virgil boarded a train for California and Wyatt Earp killed him. The local sheriff issued a warrant for the arrest of five members of the federal posse, including Holliday. The federal posse killed three other Cowboys during late March and early April 1882, before they rode to the New Mexico Territory. Wyatt Earp learned of an extradition request for Holliday and arranged for Colorado Governor Frederick Walker Pitkin to deny Holliday's extradition. Holliday spent the few remaining years of his life in Colorado. He died of tuberculosis in his bed at the Hotel Glenwood at age 36.[4]

Early life and education

[edit]

Holliday was born in Griffin, Georgia, to Henry Burroughs Holliday and Alice Jane (McKey) Holliday.[5] He was of English and Scottish ancestry.[6]: 236 His father served in the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War (as a major in the 27th Georgia Infantry).[7] When the Mexican–American War ended, Henry brought home an adopted son named Francisco. Holliday was baptized at the First Presbyterian Church of Griffin in 1852.[8] In 1864, his family moved to Valdosta, Georgia,[8] where his father would be elected mayor and his mother would die of tuberculosis on September 16, 1866.[5] The same disease killed his adopted brother. Three months after his wife's death, his father married Rachel Martin.

Holliday attended the Valdosta Institute,[8] where he received a classical education in rhetoric, grammar, mathematics, history, and languages—principally Latin, but some French and Ancient Greek.[8]

In 1870, 19-year-old Holliday left home for Philadelphia. On March 1, 1872, at age 20, he received his Doctor of Dental Surgery degree from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery (now part of the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine).[5] Holliday graduated five months before his 21st birthday, so the school held his degree until he turned 21, the minimum age required to practice dentistry.[9]: 50

Adulthood

[edit]Career

[edit]

Holliday moved to St. Louis, Missouri, so he could work as an assistant for his classmate, A. Jameson Fuches, Jr.[1]: 51 Less than four months later, at the end of July, he relocated to Atlanta, where he joined a dental practice. He lived with his uncle and his family so he could begin to build up his dental practice.[10] A few weeks before Holliday's birthday, dentist Arthur C. Ford advertised in the Atlanta papers that Holliday would substitute for him while Ford was attending dental meetings.

Fight in Georgia

[edit]There are disputed rumors that Holliday was involved in a shooting on the Withlacoochee River, Georgia, in 1873. The earliest mention is by Bat Masterson in a profile of Doc he wrote in 1907. According to that story, when Holliday was 22, he went with some friends to a swimming hole on his uncles' land, where they discovered it was occupied by a group of black U.S. Army soldiers who were in the area as part of the federal government's occupying forces in the South.[1]: 64–67

Susan McKey Thomas, the daughter of Doc's uncle Thomas S. McKey, said her father told her: "They rode in on the Negroes in swimming in a part of the Withlacoochee River that "Doc" and his friends had cleared to be used as their swimming hole. The presence of the Negroes in their swimming hole enraged "Doc," and he drew his pistol, shooting over their heads to scare them off." Papa said, "He shot over their heads!"[11]

According to Masterson's story, Holliday leveled a double-barreled shotgun at them, and when they exited the swimming hole, killed two of the youths. Some family members thought it best that Holliday leave the state, but other members of Holliday's family dispute those accounts.[1]: 64–67 Researcher and historian Gary Roberts searched for contemporary evidence of the event for many months without success. Allen Barra, an author who focuses on Wyatt Earp, also searched for evidence corroborating the incident and found no credibility in Masterson's story.[12]

Diagnosis of tuberculosis

[edit]Shortly after beginning his dental practice, Holliday was diagnosed with tuberculosis.[13] He was given only a few months to live, but was told that a drier and warmer climate might slow the deterioration of his health.[5][14] After Dr. Ford's return in September, Holliday left for Dallas, Texas, the "last big city before the uncivilized Western Frontier".[1]: 53, 55

Move to Dallas

[edit]When he arrived in Dallas, Holliday partnered with a friend of his father's, Dr. John A. Seegar.[15] They won awards for their dental work at the Annual Fair of the North Texas Agricultural, Mechanical and Blood Stock Association at the Dallas County Fair. They received all three awards: "Best set of teeth in gold", "Best in vulcanized rubber", and "Best set of artificial teeth and dental ware."[16] Their office was located along Elm Street, between Market and Austin Streets.[17] They dissolved the practice on March 2, 1874. Afterward, Holliday opened his own practice over the Dallas County Bank at the corner of Main and Lamar Streets.

With coughing spells at inopportune times from his tuberculosis, his dental practice slowly declined. Meanwhile, Holliday found he had some skill at gambling and he soon relied on it as his principal income source.[15] On May 12, 1874, Holliday and 12 others were indicted in Dallas for illegal gambling.[17] He was arrested in Dallas in January 1875 after trading gunfire with a saloon keeper, Charles Austin, but no one was injured and he was found not guilty.[5] He moved his offices to Denison, Texas, but after being fined for gambling in Dallas, he left the state.

Heads farther west

[edit]Holliday headed to Denver, Colorado, following the stage routes and gambling at towns and army outposts along the way. During the summer of 1875, he settled in Denver under the alias "Tom Mackey" and found work as a faro dealer for John A. Babb's Theatre Comique at 357 Blake Street. He got into an argument with Bud Ryan, a well-known and tough gambler. They drew knives and fought and Holliday left Ryan seriously wounded.[18]

Holliday left when he learned about gold being discovered in Wyoming. On February 5, 1876, he arrived in Cheyenne, Wyoming. He found work as a dealer for Babb's partner, Thomas Miller, who owned the Bella Union Saloon. In the autumn of 1876, Miller moved the Bella Union to Deadwood, South Dakota (site of the gold rush in the Dakota Territory), and Holliday went with him.[10]: 101–103

In 1877, Holliday returned to Cheyenne, then Denver, and eventually to Kansas, where he visited an aunt. When he left Kansas, he went to Breckenridge, Texas, where he gambled. On July 4, 1877, after a disagreement with gambler Henry Kahn, Holliday beat him repeatedly with his walking stick. Both men were arrested and fined, but Kahn was not finished. Later that same day, he shot and seriously wounded the unarmed Holliday.[10]: 106–109 On July 7, the Dallas Weekly Herald incorrectly reported that Holliday had been killed. His cousin, George Henry Holliday, moved west to help him recover.

Once healed, Holliday relocated to Fort Griffin, Texas. While dealing cards at John Shanssey's saloon, he met Mary Katharine "Big Nose Kate" Horony, a dance hall woman and occasional prostitute. "Tough, stubborn, and fearless", she was educated, but chose to work as a prostitute because she liked her independence.[19] She is the only woman with whom Holliday is known to have had a relationship.[10]: 109 [15]

Befriends Wyatt Earp

[edit]

In October 1877, outlaws led by "Dirty" Dave Rudabaugh robbed a Santa Fe Railroad construction camp in Kansas. Rudabaugh fled south into Texas. Wyatt Earp was given a temporary commission as deputy U.S. marshal. Earp left Dodge City, following Rudabaugh over 400 mi (640 km) to Fort Griffin, a frontier town on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River. Earp went to the Bee Hive Saloon, the largest in town and owned by John Shanssey, whom Earp had met in Wyoming when he was 21.[10]: 113 Shanssey told Earp that Rudabaugh had passed through town earlier in the week, but he did not know where he was headed. Shanssey suggested Earp ask gambler Doc Holliday, who had played cards with Rudabaugh.[20] Holliday told Earp that he thought Rudabaugh was headed back to Kansas. Earp sent a telegram to Ford County Sheriff Bat Masterson that Rudabaugh might be headed back in his direction.[21]

After about a month in Fort Griffin, Earp returned to Fort Clark[22] and in early 1878, he went to Dodge City, where he became the assistant city marshal, serving under Charlie Bassett. During the summer of 1878, Holliday and Horony also arrived in Dodge City, where they stayed at Deacon Cox's boarding house as Dr. and Mrs. John H. Holliday. Holliday sought to practice dentistry again, and ran an advertisement in the local paper:

DENTISTRY

J. H. Holliday, Dentist, very respectfully offers his professional services to the citizens of Dodge City and surrounding country during the summer. Office at Room No. 24 Dodge House. Where satisfaction is not given, money will be refunded.[23]

According to accounts of the following event, reported by Glenn Boyer in I Married Wyatt Earp, Earp had run two cowboys, Tobe Driscall and Ed Morrison, out of Wichita earlier in 1878. During the summer, the two cowboys—accompanied by another two dozen men—rode into Dodge and shot up the town while galloping down Front Street. They entered the Long Branch Saloon, vandalized the room, and harassed the customers. Hearing the commotion, Earp burst through the front door and before he could react, a large number of cowboys were pointing their guns at him. In another version, there were only three to five cowboys. In both stories, Holliday was playing cards in the back of the room and upon seeing the commotion, drew his weapon and put his pistol at Morrison's head, forcing him and his men to disarm, rescuing Earp from a bad situation.[24][25] No account of any such confrontation was reported by any of the Dodge City newspapers at the time.[25] Whatever actually happened, Earp credited Holliday with saving his life that day, and the two men became friends.[24][26]

Other known confrontations

[edit]Holliday was still practicing dentistry from his room in Fort Griffin, Texas, and in Dodge City, Kansas. In an 1878 Dodge newspaper advertisement, he promised money back for less than complete customer satisfaction. However, this was the last known time that he worked as a dentist.[10]: 113 He gained the nickname "Doc" during this period.[1]: 74

Holliday reportedly engaged in a gunfight with a bartender named Charles White. Miguel Otero, who would later become governor of New Mexico Territory, said he was present when Holliday walked into the saloon with a cocked revolver in his hand and challenged White to settle an outstanding argument. White was serving customers at the time and took cover behind a bar, then started shooting at Holliday with his revolver. During the fight, Holliday shot White in the scalp. However, there are no contemporaneous newspaper reports of the incident.[27][1]: 120

Bat Masterson reportedly said that Holliday was in Jacksboro, Texas, and got into a gunfight with an unnamed soldier whom Holliday shot and killed. Historian Gary L. Roberts found a record for a Private Robert Smith who had been shot and killed by an "unknown assailant" on March 3, 1876, but Holliday was never linked to the death.[1]: 78–79

Move to New Mexico

[edit]Holliday developed a reputation for his skill with a gun, as well as with the cards.[28]: 186 A few days before Christmas in 1878, Holliday and Horony arrived in Las Vegas, New Mexico.[29]: 18 [30][31]: 30–31 The 22 hot springs near the town were favored by individuals with tuberculosis for their alleged healing properties. Doc opened a dental practice and continued gambling as well, but the winter was unseasonably cold and business was slow. The New Mexico Territorial Legislature passed a bill banning gambling within the territory with surprising ease. On March 8, 1879, Holliday was indicted for "keeping [a] gaming table" and was fined $25. The ban on gambling combined with extremely low temperatures persuaded him to return to Dodge City for a few months.[31]

In September 1879, Wyatt Earp resigned as assistant marshal in Dodge City. Accompanied by his common-law wife Mattie Blaylock, his brother Jim, and Jim's wife Bessie, they left for Arizona Territory.[29]: 18 [30][31]: 30–31 Holliday and Horony returned to Las Vegas where they met again with the Earps.[30] The group arrived in Prescott in November.

Royal Gorge War

[edit]In Dodge City, Holliday joined a team being formed by Deputy U.S. Marshal Bat Masterson. Masterson had been asked to prevent an outbreak of guerrilla warfare between the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway and the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad (D&RGW), which were vying to be the first to claim a right-of-way across the Royal Gorge, one of the few natural routes through the Rockies that crossed the Continental Divide. Both were striving to be the first to provide rail access to the boom town of Leadville, Colorado.[32] Royal Gorge was a bottleneck along the Arkansas, too narrow for both railroads to pass through, and with no other reasonable access to the South Park area. Doc remained there for about two and a half months. The federal intervention prompted the so-called "Treaty of Boston" to end the fighting. The D&RGW completed its line and leased it for use by the Santa Fe.[33] Holliday took home a share of a $10,000 bribe paid by the D&RGW to Masterson to give up their possession of the Santa Fe roundhouse and returned to Las Vegas where Horony had remained.

Builds saloon in Las Vegas

[edit]The Santa Fe Railroad built tracks to Las Vegas, New Mexico, but bypassed the city by about a mile. A new town was built up near the tracks and prostitution and gambling flourished there. On July 19, 1879, Holliday and John Joshua Webb, former lawman and gunman, were seated in a saloon. Former U.S. Army scout Mike Gordon tried to persuade one of the saloon girls, a former girlfriend, to leave town with him. She refused and Gordon left the building "shouting obscenities", followed by Holliday. Gordon fired a shot at Holliday and subsequently "Gordon died" the day after.[34] The next day, Holliday paid $372.50 to a carpenter to build a clapboard building to house the Doc Holliday's Saloon with John Webb as his partner. While in town, he was fined twice for keeping a gambling device, and again for carrying a deadly weapon.[6]: 134

Move to Arizona Territory

[edit]It appeared Holliday and Horony were settling into life in Las Vegas when Wyatt Earp arrived on October 18, 1879. He told Holliday he was headed for the silver boom going on in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Holliday and Horony joined Wyatt and his wife Mattie, as well as Jim Earp and his wife and stepdaughter, and they left the next day for Prescott, Arizona Territory. They arrived within a few weeks and went straight to the home of Constable Virgil Earp and his wife Allie. Holliday and Horony checked into a hotel and when Wyatt, Virgil, and James Earp with their wives left for Tombstone, Holliday remained in Prescott, where he thought the gambling opportunities were better.[29][6]: 134 Sometime in spring of 1880, Holliday and Kate Horony separate, with Horony leaving for Globe. Holliday left Prescott in the spring of 1880 to return to Las Vegas and resolve old legal and business matters. He was back by June of that year. Upon his return, Holliday lived in a boarding house, located at 100 N. Montezuma St., which was owned by temperance leader Richard Elliott. Arizona Secretary of State, and acting governor, John Gosper, also lived there. Although there is no indication Holliday practiced, in the June 1880 census he listed his profession as 'dentist'. One of two known photographs of Holliday was taken in Prescott, by photographer D.F. Mitchell (the other photo is Holliday's dental school graduation photo).

Holliday finally joined the Earps in Tombstone in September 1880. Some accounts report that the Earps sent for Holliday for assistance with dealing with the outlaw Cowboys. Holliday quickly became embroiled in the local politics and violence that led up to the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in October 1881.

Accused in stagecoach robbery

[edit]Holliday and Horony had many fights. After a particularly nasty, drunken argument, Holliday kicked her out. County Sheriff Johnny Behan and Milt Joyce, both members of the Ten Percent Ring, saw an opportunity and exploited the situation. They plied Horony with more liquor and suggested to her a way to get even with Holliday. She signed an affidavit implicating Holliday in an attempted robbery and murder of passengers aboard a Kinnear and Company stage coach on March 15, 1881, carrying US$26,000 in silver bullion (equivalent to $821,000 in 2023).

Bob Paul, who had run for Pima County sheriff and was contesting the election he lost due to ballot stuffing, was working as the Wells Fargo shotgun messenger. He had taken the reins and driver's seat in Contention City because the usual driver, a well-known and popular man named Eli "Budd" Philpot, was ill. Paul was riding in Philpot's place as shotgun when three cowboys stopped the stage between Tombstone and Benson, Arizona, and tried to rob it.[35]: 180

Paul fired his shotgun and emptied his revolver at the robbers, wounding a cowboy, later identified as Bill Leonard, in the groin. Philpot and passenger Peter Roerig, riding in the rear dickey seat, were both shot and killed.[36] Holliday was a good friend of Leonard, a former watchmaker from New York.[37]: 181 Based on the affidavit sworn by Horony, Judge Wells Spicer issued an arrest warrant for Holliday.[38] Rumors flew that Holliday had taken part in the shooting and murders.

Later that day Holliday returned, drunk, to Joyce's saloon. He insulted Joyce and demanded his firearm back. Joyce refused and threw him out, but Holliday came back carrying a revolver and started firing. Joyce pulled out a pistol and Holliday shot the revolver out of Joyce's hand, putting a bullet through his palm. When Joyce's bartender, Parker, tried to grab his gun, Holliday wounded him in the toe. Joyce picked up his pistol and pistol-whipped Holliday, knocking him out. He shot and wounded both men and was convicted of assault.[39][40][38]

The Earps found witnesses who could attest to Holliday's location elsewhere at the time of the stagecoach murders, and a sober Horony confessed that Behan and Joyce had influenced her to sign a document she did not understand. With the cowboy plot revealed, Spicer freed Holliday. The district attorney dismissed the charges, labeling them "ridiculous". Holliday gave Horony some money and put her on a stage out of town.[38]

Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

[edit]On October 26, 1881, Virgil Earp was both a deputy U.S. marshal and Tombstone's city police chief. He received reports that cowboys with whom they had had repeated confrontations were armed in violation of the city ordinance that required them to deposit their weapons at a saloon or stable soon after arriving in town. The cowboys had repeatedly threatened the Earps and Holliday. Fearing trouble, Virgil temporarily deputized Holliday and sought backup from his brothers Wyatt and Morgan. Virgil retrieved a short coach gun from the Wells Fargo office and the four men went to find the cowboys.[41]

On Fremont Street, they ran into Cochise County Sheriff Behan, who told them or implied that he had disarmed the cowboys. To avoid alarming citizens and lessen tension when disarming the cowboys, Virgil gave the coach gun to Holliday so he could conceal it under his long coat. Virgil Earp took Holliday's walking stick.[42] The lawmen found the cowboys in a narrow 15- to 20-ft-wide lot on Fremont Street, between Fly's boarding house and the Harwood house. Holliday was boarding at Fly's house and he possibly thought they were waiting there to kill him.[43]

Different witnesses offered varying stories about Holliday's actions. Cowboys' witnesses testified that Holliday first pulled out a nickel-plated pistol he was known to carry, while others reported he first fired a longer, bronze-colored gun, possibly the coach gun. Holliday killed Tom McLaury with a shotgun blast in the side of his chest. Holliday was grazed by a bullet possibly fired by Frank McLaury who was on Fremont Street at the time. He supposedly challenged Holliday, yelling, "I've got you now!" Holliday is reported to have replied, "Blaze away! You're a daisy if you have." McLaury died of shots to his stomach and behind his ear. Holliday may have also wounded Billy Clanton.[44]

One analysis of the fight gives credit to either Holliday or Morgan Earp for firing the fatal shot at McLaury on Fremont Street. Holliday may have been on McLaury's right and Morgan Earp on his left. McLaury was shot in the right side of the head, so Holliday is often given credit for shooting him. However, Wyatt Earp had shot McLaury in his torso earlier, a shot that alone could have killed him. McLaury would have turned away after having been hit and Wyatt could have placed a second shot in his head.[45][46] A 30-day-long preliminary hearing found that the Earps and Holliday had acted within their duties as lawmen, although this did not pacify Ike Clanton.

Earp Vendetta Ride

[edit]The situation in Tombstone soon grew worse when Virgil Earp was ambushed and permanently injured in December 1881. Following that, Morgan Earp was ambushed and killed in March 1882. Several Cowboys were identified by witnesses as suspects in the shooting of Virgil Earp on December 27, 1881, and the assassination of Morgan Earp on March 19, 1882. Additional circumstantial evidence also pointed to their involvement. Wyatt Earp had been appointed deputy U.S. marshal after Virgil was maimed. He deputized Holliday, Warren Earp, Sherman McMaster, and "Turkey Creek" Jack Johnson.

After Morgan's murder, Wyatt Earp and his deputies guarded Virgil Earp and Allie on their way to the train for Colton, California where his father lived, to recuperate from his serious shotgun wound. In Tucson, on March 20, 1882, the group spotted an armed Frank Stilwell and reportedly Ike Clanton hiding among the railroad cars, apparently lying in wait with the intent to kill Virgil. Frank Stilwell's body was found at dawn alongside the railroad tracks, riddled with buckshot and gunshot wounds.[47] Wyatt said later in life that he killed Stilwell with a shotgun.[48]

Tucson Justice of the Peace Charles Meyer issued arrest warrants for five of the Earp party, including Holliday. On March 21, they returned briefly to Tombstone, where they were joined by Texas Jack Vermillion and possibly others. On the morning of March 22, a portion of the Earp posse including Wyatt, Warren, Holliday, Sherman McMaster, and "Turkey Creek" Johnson rode about 10 mi (16 km) east to Pete Spence's ranch to a wood cutting camp located off the Chiricahua Road, below the South Pass of the Dragoon Mountains.[34][49][9]: 250 According to Theodore Judah—who witnessed events at the wood camp—the Earp posse arrived around 11:00 a.m. and asked for Spence and Florentino "Indian Charlie" Cruz. They learned Spence was in jail[47] and that Cruz was cutting wood nearby. They followed the direction Judah indicated and he soon heard a dozen or so shots. When Cruz did not return the next morning, Judah went looking for him and found his body full of bullet holes.[50]

Gunfight at Iron Springs

[edit]Two days later, Earp's posse traveled to Iron Springs, located in the Whetstone Mountains, where they expected to meet Charlie Smith, who was supposed to be bringing $1,000 cash from their supporters in Tombstone. With Wyatt and Holliday in the lead, the six lawmen surmounted a small rise overlooking the springs. They surprised eight cowboys camping near the springs. Wyatt Earp and Holliday left the only record of the fight. Curly Bill recognized Wyatt Earp in the lead and immediately grabbed his shotgun and fired at Earp. The other Cowboys also drew their weapons and began firing. Earp dismounted, shotgun in hand. "Texas Jack" Vermillion's horse was shot and fell on him, pinning his leg and wedging his rifle underneath. Lacking cover, Holliday, Johnson, and McMaster retreated.[51]

Earp returned Curly Bill's gunfire with his own shotgun and shot him in the chest, nearly cutting him in half according to Earp's later account.[51] Curly Bill fell into the water by the edge of the spring and lay dead.[52]

The Cowboys fired a number of shots at the Earp party, but the only casualty was Vermillion's horse, which was killed. Firing his pistol, Wyatt shot Johnny Barnes in the chest and Milt Hicks in the arm. Vermillion tried to retrieve his rifle wedged in the scabbard under his fallen horse, exposing himself to the Cowboys' gunfire. Doc Holliday helped him gain cover. Wyatt had trouble re-mounting his horse because his cartridge belt had slipped down around his legs.[51]

Wyatt's long coat was shot through by bullets on both sides. Another bullet struck his boot heel and his saddle horn was hit as well, burning the saddle hide and narrowly missing Wyatt. He was finally able to get on his horse and retreat. McMaster was grazed by a bullet that cut through the straps of his field glasses.[47]

Earp and Holliday part company

[edit]Holliday and four other members of the posse were still faced with warrants for Stilwell's death. The group elected to leave the Arizona Territory for New Mexico Territory and then on to Colorado. Wyatt and Holliday, who had been fast friends, had a serious disagreement and parted ways in Albuquerque.[53] According to a letter written by former New Mexico Territory Governor Miguel Otero, Wyatt and Holliday were eating at Fat Charlie's The Retreat Restaurant in Albuquerque "when Holliday said something about Earp becoming 'a damn Jew-boy.' Earp became angry and left ..."

Earp was staying with a prominent businessman, Henry N. Jaffa, who was also president of New Albuquerque's Board of Trade. Jaffa was Jewish, and based on Otero's letter, Earp had, while staying in Jaffa's home, honored Jewish tradition by touching the mezuzah upon entering his home. According to Otero's letter, Jaffa told him, "Earp's woman was a Jewess." Earp's anger at Holliday's ethnic slur may indicate that the relationship between Josephine Marcus and Wyatt Earp was more serious at the time than is commonly known.[54][55] Holliday and Dan Tipton arrived in Pueblo, Colorado in late April 1882.[1]

Arrives in Colorado

[edit]On May 15, 1882, Holliday was arrested in Denver on the Tucson warrant for murdering Frank Stilwell. When Wyatt Earp learned of the charges, he feared his friend Holliday would not receive a fair trial in Arizona. Earp asked his friend Bat Masterson, then chief of police of Trinidad, Colorado, to help get Holliday released. Masterson drew up bunco charges against Holliday.[56]

Holliday's extradition hearing was set for May 30. Late in the evening of May 29, Masterson sought help getting an appointment with Colorado Governor Frederick Walker Pitkin. He contacted E.D. Cowen, capital reporter for the Denver Tribune, who held political sway in town. Cowen later wrote, "He submitted proof of the criminal design upon Holliday's life. Late as the hour was, I called on Pitkin." His legal reasoning was that the extradition papers for Holliday contained faulty legal language and that there was already a Colorado warrant out for Holliday—including the bunco charge that Masterson had fabricated. Pitkin was persuaded by the evidence presented by Masterson and refused to honor Arizona's extradition request.[56]: 230

Masterson took Holliday to Pueblo, where he was released on bond two weeks after his arrest.[57] Holliday and Wyatt met again in June 1882 in Gunnison after Wyatt helped to keep his friend from being convicted on murder charges regarding Frank Stillwell.[57] Holliday was able to see his old friend Wyatt one last time in the late winter of 1886, where they met in the lobby of the Windsor Hotel. Sadie Marcus described the skeletal Holliday as having a continuous cough and standing on "unsteady legs."[58]

Death of Johnny Ringo

[edit]On July 14, 1882, Holliday's long-time enemy Johnny Ringo was found dead in a low fork of a large tree in West Turkey Creek Valley near Chiricahua Peak, Arizona Territory. He had a bullet hole in his right temple and a revolver was found hanging from a finger of his hand. A coroner's inquest officially ruled his death a suicide;[59] but according to the book I Married Wyatt Earp, which author and collector Glenn Boyer claimed to have assembled from manuscripts written by Earp's third wife, Josephine Marcus Earp, Earp and Holliday traveled to Arizona with some friends in early July, found Ringo in the valley, and killed him.[60] Boyer refused to produce his source manuscripts, and reporters wrote that his explanations were conflicting and not credible. New York Times contributor Allen Barra wrote that the book "is now recognized by Earp researchers as a hoax".[61]: 154 [62] A variant of the story, popularized in the movie Tombstone, holds that Holliday stepped in for Earp in response to a gunfight challenge from Ringo, and shot him.[60]

Evidence is unclear as to Holliday's exact whereabouts on the day of Ringo's death. Records of the District Court of Pueblo County, Colorado indicate that Holliday and his attorney appeared in court in Pueblo on July 11, and again on July 14 to answer charges of "larceny"; but a writ of capias was issued for him on the 11th, suggesting that he may not have been in court that day.[63] The Pueblo Daily Chieftain reported that Holliday was seen in Salida, Colorado on July 7, more than 550 miles (890 km) from where Ringo's body was found, and then in Leadville on July 18.[64] Holliday biographer Karen Holliday Tanner noted that there was still an outstanding murder warrant in Arizona for Holliday's arrest, making it unlikely that he would choose to re-enter Arizona at that time.[65]

Hired by James Kyner

[edit]Toward the end of the 1880s, railroad contractor James H. Kyner hired Doc Holliday to motivate the proprietors of dozens of gambling and saloon tents to leave the forty-one-mile stretch of railroad line that he and another contractor were constructing between Glenwood Springs and Aspen. Drunkenness of the workers boozing it up at the saloon tents was causing trouble and there were too many for Kyner to want to deal with the problem himself.[66]

Kyner had heard that a gunman named Doc Holliday had been hired before by a group of men who wanted to drive off others who had staked claims to the same nearby coal deposit that they were claiming, which gave him the idea of hiring Holliday to make his troublemakers leave. Kyner was staying at the Glenwood Hotel and when Holliday was pointed out to him one day, he initiated a discussion about it. Without hesitation, Holliday told Kyner he could do it for $250.[66]

Kyner was later told by several men that every saloon and gambling tent along that line had disappeared, except one that was in a draw a half mile from the line. He met Holliday the next evening and asked "What luck?". Holliday replied "Oh, they moved," and without another word Kyner paid him the $250.[66]

Shooting of William J. "Billy" Allen

[edit]Holliday's last known confrontation took place in Hyman's saloon in Leadville, Colorado in 1884. Down to his last dollar, he had pawned his jewelry, and then borrowed $5 (equivalent to $170 in 2023) from William J. "Billy" Allen. Allen was a bartender and special officer at the Monarch Saloon (and a former policeman), which enabled Allen to carry a gun and make arrests within the Monarch saloon. When Allen repeatedly demanded he be re-paid by August 19 "or else", Holliday could not comply and was afraid. Doc knew that Allen usually stopped by Hyman's saloon when he was finished at the Monarch, so Doc planned to confront Allen at Hyman's on August 19. On his way to Hyman's, Doc bumped into Marshall Harvey Faucett and explained his situation. Faucett informed Doc that Allen couldn't carry a weapon outside the Monarch. Faucett testified later that Doc replied, "I'll get a shotgun and shoot him on sight," showing his intent. Faucett then went to the Monarch to warn Allen, but Allen had already left for Hyman's. Doc went on to Hyman's where he stashed a gun near the door under the bar and waited for Allen to appear. As Allen left the Monarch, Cy Allen (one of the Monarch's proprietors) "warned him against hunting up Holliday just then. Billy Allen answered there would be no trouble and, with a careless air, walked out" towards Hyman's.[67]

When Allen came through Hyman's door, Doc reached under the bar, grabbed his gun, and shot at Allen; the first shot missed Allen and slammed into the door frame. "Startled, Allen spun on his heel, intending to flee, but tripped over the threshold and pitched forward, landing on his hands and knees. The ex-policeman scrambled to get to his feet. Holliday leaned over the cigar case and, almost on top of the man who’d been the hunter only seconds earlier, fired again. This shot hit its mark. The bullet tore into Allen’s right arm from the rear about halfway between the shoulder and the elbow and passed clear through, severing an artery in its flight. Jolted upright, Allen stumbled outside. He staggered against the wall of Dave May’s clothing store next door. By now he was in shock and bleeding freely, and he fainted into the arms of an onlooker." Allen’s main artery was sewn up by Dr. F. F. D'Avignon and he survived, although his arm was always “funny” afterward.[67]

Doc Holliday was arrested and put on trial. During the trial, "the preponderance of testimony at Holliday’s hearing went to show that Allen was not armed (no gun was ever found), but by then the overriding Western credo of 'no duty to retreat' had won the day with public sentiment. 'No duty to retreat' was a belief, enacted in the laws of several states, that a man who was without blame for provoking a confrontation was not obliged to flee from his assailant but was free to stand his ground regardless of the consequences." He claimed self-defense, noting that Allen outweighed him by 50 pounds (23 kg) and he feared for his life. On March 28, 1885, the jury acquitted Holliday. [67]

Holliday spent his remaining days in Colorado. After a stay in Leadville, he suffered from the high altitude. He increasingly depended on alcohol and laudanum to ease the symptoms of tuberculosis, and his health and his skills as a gambler began to deteriorate.[10]: 218

Final days and death

[edit]

In 1887, prematurely gray and badly ailing, Holliday made his way to the Hotel Glenwood, near the hot springs of Glenwood Springs, Colorado.[68] He hoped to take advantage of the reputed curative power of the waters, but the sulfurous fumes from the spring might have done his lungs more harm than good.[10]: 217 As he lay dying, Holliday is reported to have asked the nurse attending him for a shot of whiskey. When she told him no, he looked at his bootless feet, amused. The nurses said that his last words were, "This is funny."[8] He always figured he would be killed someday with his boots on.[1]: 372 Holliday died at 10 a.m. on November 8, 1887. He was 36.[16] Wyatt Earp did not learn of Holliday's death until two months afterward. Kate Horony later said that she attended to him in his final days, and one contemporary source appears to corroborate her claim.[69] He died from tuberculosis.[70]

Memorial service

[edit]The Glenwood Springs Ute Chief of November 12, 1887, wrote in its obituary that Holliday had been baptized in the Catholic Church. This was based on correspondence written between Holliday and his cousin, Sister Mary Melanie, a Catholic nun. No baptismal record has been found in either St. Stephen's Catholic Church in Glenwood Springs or at the Annunciation Catholic Church in nearby Leadville.[10]: 300

Holliday's mother had been raised a Methodist and later joined a Presbyterian church (her husband's faith), but objected to the Presbyterian doctrine of predestination and re-converted to Methodism publicly before she died, saying that she wanted her son John to know what she believed.[1]: 14, 41 Holliday himself was later to say that he had joined a Methodist church in Dallas.[1]: 70 At the end of his life, Holliday had struck up friendships with both a Catholic priest, Father E.T. Downey, and a Presbyterian minister, Rev. W.S. Randolph, in Glenwood Springs. When he died, Father Downey was out of town, and so Rev. Randolph presided over the burial at 4 p.m. on the same day that Holliday died. The services were reportedly attended by "many friends".[1]: 370, 372

Burial

[edit]Holliday is buried in Linwood Cemetery overlooking Glenwood Springs. Since Holliday died in November, the ground might have been frozen. Some modern authors such as Bob Boze Bell[71] speculate that it would have been impossible to transport him to the cemetery, which was only accessible by a difficult mountain road, or to dig a grave because the ground was frozen. Author Gary Roberts located evidence that other bodies were transported to the Linwood Cemetery at the same time of the month that year. Contemporary newspaper reports explicitly state that Holliday was buried in the Linwood Cemetery, but the exact location of his grave is uncertain.[1]: 403–404 Though there is no official evidence of this, some claim that Holliday's father, Major Henry Holliday, a man of means and influence, had his son exhumed and re-buried in Griffin's Oak Hill Cemetery.[72]

Public reputation

[edit]Holliday maintained a fierce persona as was sometimes needed for a gambler to earn respect. He had a contemporary reputation as a skilled gunfighter which modern historians generally regard as accurate.[1]: 410 Tombstone resident George W. Parsons wrote that Holliday confronted Johnny Ringo in January 1882, telling him, "All I want of you is ten paces out in the street." Ringo and he were prevented from a gunfight by the Tombstone police, who arrested both. During the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Holliday initially carried a shotgun and shot at and may have killed Tom McLaury. Holliday was grazed by a bullet fired by Frank McLaury and shot back. After Virgil was maimed in a January ambush, Holliday was part of a federal posse led by Deputy U.S. Marshal Wyatt Earp who guarded him on his way to the railroad in Tucson. There they found Frank Stilwell apparently waiting for the Earps in the rail yard. A warrant for Holliday's arrest was issued after Stilwell was found dead with multiple gunshot wounds. Holliday was part of Earp's federal posse when they killed three other outlaw Cowboys during the Earp Vendetta Ride. Holliday reported that he had been arrested 17 times, four attempts had been made to hang him, and that he survived ambush five times.[73]

Character

[edit]Throughout his lifetime, Holliday was known by many of his peers as a tempered, calm, Southern gentleman. In an 1896 article, Wyatt Earp said: "I found him a loyal friend and good company. He was a dentist whom necessity had made a gambler; a gentleman whom disease had made a vagabond; a philosopher whom life had made a caustic wit; a long, lean blonde fellow nearly dead with consumption and at the same time the most skillful gambler and nerviest, speediest, deadliest man with a six-gun I ever knew."[74]

In a newspaper interview, Holliday was once asked if his conscience ever troubled him. He is reported to have said, "I coughed that up with my lungs, years ago."[75]: 189

Bat Masterson had several contacts with Holliday over his lifetime and the two men developed a dislike for each other. They tolerated each other only as friends of Wyatt Earp. Masterson wrote in an article about Holliday,

While he never did anything to entitle him to a Statue in the Hall of Fame, Doc Holliday was nevertheless a most picturesque character on the western border in those days when the pistol instead of law determined issues.... Holliday had a mean disposition and an ungovernable temper, and under the influence of liquor was a most dangerous man…. Physically, Doc Holliday was a weakling who could not have whipped a healthy fifteen-year-old boy in a go-as-you-please fistfight.[21]

Masterson wrote that Holliday was quick to go for his gun when threatened.[21]

Stabbings and shootings

[edit]Much of Holliday's violent reputation was nothing but rumors and self-promotion. However, he showed great skill in gambling and gunfights. His tuberculosis did not hamper his ability as a gambler and as a marksman. Holliday was ambidextrous.[43]: 96

No contemporaneous newspaper accounts or legal records offer proof of the many unnamed men whom Holliday is credited with killing in popular folklore. The only men he is known to have killed are Mike Gordon in 1879; probably Frank McLaury and Tom McLaury in Tombstone; possibly Frank Stilwell in Tucson; and William Allen in Colorado. Some scholars argue that Holliday may have encouraged the stories about his reputation, although there is no evidence he did.[1]: 410

In a March 1882 interview with the Arizona Daily Star, Virgil Earp told the reporter:

There was something very peculiar about Doc. He was gentlemanly, a good dentist, a friendly man, and yet outside of us boys I don't think he had a friend in the Territory. Tales were told that he had murdered men in different parts of the country; that he had robbed and committed all manner of crimes, and yet when persons were asked how they knew it, they could only admit that it was hearsay and that nothing of the kind could really be traced up to Doc's account.[76]

Arrests and convictions

[edit]Biographer Karen Holliday Tanner found that Holliday had been arrested 17 times before his 1881 shootout in Tombstone. Only one arrest was for murder, which occurred in an 1879 shootout with Mike Gordon in New Mexico, for which he was acquitted. In the preliminary hearing following the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Judge Wells Spicer exonerated Holliday's actions as those of a duly appointed lawman. In Denver, the Arizona warrant against Holliday for Frank Stilwell's murder went unserved when the governor was persuaded by Trinidad Chief of Police Bat Masterson to release Holliday to his custody for bunco charges.[10]

Among his other arrests, Holliday pleaded guilty to two gambling charges, one charge of carrying a deadly weapon in the city (in connection with the argument with Ringo), and one misdemeanor assault and battery charge (for his shooting of Joyce and Parker). The others were all dismissed or returned as "not guilty."[10]

Alleged murder of Ed Bailey

[edit]Wyatt Earp recounted one event during which Holliday killed a fellow gambler named Ed Bailey. Earp and his common-law wife Mattie Blaylock were in Fort Griffin, Texas, during the winter of 1878, looking for gambling opportunities. Earp visited the saloon of his old friend from Cheyenne, John Shannsey, and met Holliday at the Cattle Exchange.[77] The story of Holliday killing Bailey first appeared nine years after Holliday's death in an 1896 interview with Wyatt Earp that was published in the San Francisco Enquirer.[78]

According to Earp, Holliday was playing poker with a well-liked local man named Ed Bailey. Holliday caught Bailey "monkeying with the dead wood" or the discard pile, which was against the rules. According to Earp, Holliday reminded Bailey to "play poker", which was a polite way to caution him to stop cheating. When Bailey made the same move again, Holliday took the pot without showing his hand, which was his right under the rules. Bailey immediately went for his pistol, but Holliday whipped out a knife from his breast pocket and "caught Bailey just below the brisket" or upper chest. Bailey died and Holliday, new to town, was detained in his room at the Planter's Hotel.[10]: 115

In Stuart Lake's best-selling biography, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal (1931), Earp added to the story. He is quoted as saying that Holliday's girlfriend, "Big Nose Kate" Horony, devised a diversion. She procured a second pistol from a friend in town, removed a horse from its shed behind the hotel, and then set fire to the shed. Everyone but Holliday and the lawmen guarding him ran to put out the fire, while she calmly walked in and tossed Holliday the second pistol.[77]

However, no contemporary records have been found of either Bailey's death or of the shed fire. In addition, Horony denied that Holliday killed "a man named Bailey over a poker game, nor was he arrested and locked up in another hotel room." She laughed at the idea of "a 116-pound woman, standing off a deputy, ordering him to throw up his hands, disarming him, rescuing her lover, and hustling him to the waiting ponies."[1]: 87

Author and Earp expert Ben Traywick doubts that Holliday killed Bailey. He found no contemporary newspaper articles or court records to support the story. He found evidence to support that Holliday was being held in his hotel room under guard, but for "illegal gambling", and that the story of Horony starting a fire as a diversion to free him was true. The story about Bailey as told in San Francisco Enquirer interview of Earp was likely fabricated by the writer. Years later, Earp wrote:

Of all the nonsensical guff which has been written around my life, there has been none more inaccurate or farfetched than that which has dealt with Doc Holliday. After Holliday died, I gave a San Francisco newspaper reporter a short sketch of his life. Apparently, the reporter was not satisfied. The sketch appeared in print with a lot of things added that never existed outside the reporter's imagination ...[78]

Photos of Holliday

[edit]Three photos of unknown provenance are often reported to be of Holliday, some of them supposedly taken by C.S. Fly in Tombstone, but sometimes reported to have been taken in Dallas. Holliday lived in a rooming house in front of Fly's photography studio. Many persons share similar facial features, and the faces of people who look radically different can look similar when viewed from certain angles. Because of this, most museum staff, knowledgeable researchers, and collectors require provenance or a documented history for an image to support physical similarities that might exist. Experts rarely offer even a tentative identification of new or unique images of famous people based solely on similarities shared with other known images.[79]

-

Cropped from a larger version, Holliday's graduation photo from the Pennsylvania School of Dental Surgery in March 1872, age 20, known provenance and authenticated as Holliday

-

Cropped from a larger version, Holliday in Prescott, Arizona in 1879, age 27, known provenance and authenticated as Holliday

-

Uncreased print of supposed 1882 Tombstone photo of Holliday, left side is upturned, detachable shirt collar toward camera, no cowlick, unknown provenance

-

Creased and darker version of photo at left, unknown provenance

-

Person most often reported to be Holliday with a cowlick and folded-down collar, heavily retouched, oval, inscribed portrait, unknown provenance

-

Person with a bowler hat and open vest and coat, unknown provenance

Legacy

[edit]

Doc Holliday is one of the most recognizable figures in the American Old West, but he is most remembered for his friendship with Wyatt Earp and his role in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Holliday's friendship with the lawman has been a staple of popular sidekicks in American Western culture,[80] and Holliday himself became a stereotypical image of a deputy and a loyal companion in modern times. He is typically portrayed in films as being loyal to his friend Wyatt, whom he sticks with during the duo's greatest conflicts, such as the Gunfight at the OK Corral and Earp's vendetta, even with the ensuing violence and hardships that they both endured.[1] Together with Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday has become a modern symbol of loyalty, brotherhood and friendship.[81]

The home of Doc Holliday’s uncle is marked with a historical marker located in Fayetteville, Georgia.[82]

A life-sized statue of Holliday and Earp by sculptor Dan Bates was dedicated by the Southern Arizona Transportation Museum at the restored Historic Railroad Depot in Tucson, Arizona, on March 20, 2005, the 122nd anniversary of the killing of Frank Stilwell by Wyatt Earp. The statue stands at the approximate site of the shooting on the train platform.[83][84]

"Doc Holliday Days" are held yearly in Holliday's birthplace of Griffin, Georgia. Valdosta, Georgia held a Doc Holliday look-alike contest in January 2010, to coincide with its sesquicentennial celebration.[85]

Tombstone, Arizona also holds an annual Doc Holli-Days, which started in 2017 and celebrates the gunfighter-dentist on the 2nd weekend of August each year. Events include gunfights, a parade, and a Doc Holliday look-alike contest. Val Kilmer, who played Doc in 1993's Tombstone, was the grand marshal in 2017 and Dennis Quaid, who played Doc in 1994's Wyatt Earp, was the grand marshal in 2018.[86]

In popular culture

[edit]Holliday was nationally known during his life as a gambler and gunman. The shootout at the O.K. Corral is one of the most famous frontier stories in the American West and numerous Western TV shows and movies have been made about it. Holliday is usually a prominent part of the story.[6][87]

Documentary

[edit]- In Search of Doc Holliday (2016)

In film and television

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

Actors who have portrayed Holliday include:

- Harvey Clark in Law for Tombstone (1937)

- Cesar Romero in Frontier Marshal (1939)

- Kent Taylor in Tombstone, the Town Too Tough to Die (1942)

- Walter Huston in The Outlaw (1943)

- Victor Mature in My Darling Clementine directed by John Ford, with Henry Fonda as Wyatt Earp (1946)

- Harry Bartell in the 13th episode of the CBS radio program Gunsmoke (July 19, 1952)

- Kim Spalding in the syndicated television series Stories of the Century (1954)

- James Griffith in Masterson of Kansas (1954)

- Barry Atwater in "The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral", an episode of the CBS TV series You Are There, November 6, 1955

- Kirk Douglas in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957) with Burt Lancaster as Wyatt Earp

- Douglas Fowley in The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp with Hugh O'Brian as Wyatt Earp (1955–1961)

- Myron Healey in ten episodes of The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp.

- Adam West in separate 1959 episodes of Lawman, Sugarfoot (episode: "Trial of the Canary Kid"), and Colt .45

- Gerald Mohr and Peter Breck each played Holliday in the ABC/WB series Maverick (1957–62) starring James Garner and Jack Kelly

- Christopher Dark in an episode of the NBC series Bonanza (1963)

- Martin Landau in the episode "Doc Holliday" of the TV series Tales of Wells Fargo (1959)

- Robert Lansing in The Tall Man episode "Rovin' Gambler" (1961)

- Anthony Jacobs in the Doctor Who episode "The Gunfighters" (1966)

- Warren Stevens in the episode "Doc Holliday's Gold Bars" of the syndicated Western series, Death Valley Days (1966)[88]

- Jason Robards in Hour of the Gun, James Garner played Wyatt Earp (1967)

- Jack Kelly in The High Chaparral (1967)

- Sam Gilman in the Star Trek episode "Spectre of the Gun" (1968)

- Stacy Keach in Doc (1971)

- Bill Fletcher in two episodes of the TV series Alias Smith and Jones: "Which Way to the OK Corral?" (1971) and "The Ten Days That Shook Kid Curry" (1972)

- John McLiam in Bret Maverick (1981)

- Jeffrey DeMunn in I Married Wyatt Earp (1983)

- Willie Nelson in Stagecoach (1986)[89]

- Val Kilmer in Tombstone (1993)

- Dennis Quaid in Wyatt Earp (1994)

- Randy Quaid in Purgatory (1999)

- Wilson Bethel in Wyatt Earp's Revenge (2012)

- Ryan Kennedy in Hannah's Law (2012)

- William McNamara in Doc Holliday's Revenge (2014)

- Shane O'Loughlin in Legends and Lies: The Real West on the Fox News Channel series that explores famous figures from the American West

- Tim Rozon in Wynonna Earp (2016–2021) [90]

- Edgar Fox in The American West (2016)

- Eric Schumacher in Tombstone Rashomon (2017)

- Jeremy Renner in Untitled Doc Holliday Biopic (TBA) based on Mary Doria Russell's books[91]

In fiction

[edit]- Epitaph: a Novel of the O.K. Corral by Mary Doria Russell, 2015 ISBN 978-0062198761

- A Wicked Little Town: Book One of The Doc Holliday Series by Elena Sandidge, 2013 ISBN 978-0992807009

- Southern Son: The Saga of Doc Holliday by Victoria Wilcox, 2013 ISBN 978-1908483553

- Holliday, Nate Bowden and Doug Dabbs, 2012 ISBN 978-1934964651

- Doc: A Novel by Mary Doria Russell, 2011 ISBN 978-1400068043

- Merkabah Rider: The Mensch With No Name by Edward M. Erdelac, a novel in the Weird West genre, 2010, ISBN 978-1615721900

- The Buntline Special by Mike Resnick, 2010, ISBN 978-1616142490

- Territory by Emma Bull, 2007 ISBN 978-0812548365

- O.K. Corral, a Lucky Luke comic by artist Morris & writers Eric Adam and Xavier Fauche 1997

- The Last Ride of German Freddie by Walter Jon Williams, a novella in Worlds that Weren't, 2005, ISBN 978-1101212639

- The Langoliers by Stephen King, a novella in Four Past Midnight, 1990, ISBN 978-0670835386

- Bucking the Tiger: A Novel by Bruce Olds, 2002 ISBN 978-0312420246

- The Fourth Horseman by Randy Lee Eickhoff, 1998 ISBN 0312853017

- Deadlands a tabletop role-playing game produced by Pinnacle Entertainment Group in Law Dogs, 1996, ISBN 978-1889546261

- Wild Times by Brian Garfield, 1978 ISBN 978-0671243746

- The Last Kind Words Saloon by Larry McMurtry, 2014 ISBN 978-0871407863

- At Grave's End by Jeaniene Frost, 2008 ISBN 978-0061583070

In song

[edit]- "Linwood", written and performed by Jon Chandler on The Grand Dame of the Rockies – Songs of the Hotel Colorado and the Roaring Fork Valley; winner of the 2009 Western Writers of America Spur Award for Best Song.[92]

- Danish metal band Volbeat performs the song "Doc Holliday" on their album Outlaw Gentlemen & Shady Ladies.[93]

- Swedish power metal band Civil War performs the song "Tombstone" about the gunfight at OK Corral on their album The Last Full Measure.[94]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Roberts, Gary L. (2006). Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0471262919.: 407–409

- ^ "Gambling in the Old West". History Net. Wild West Magazine. June 12, 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Gary L. (2011). Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend. John Wiley & Sons. p. 29. ISBN 978-1118130971.

- ^ "A New Tombstone Sets the Record Straight for Doc Holliday". The New York Times. Associated Press. October 17, 2004. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "John Henry Holliday Family History". Kansas Heritage Group. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Tanner, Karen Holliday (1998). Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806130369.

- ^ "Civil War Soldiers and Sailors". nps.gov. The National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 14, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Poling, Dean (January 1, 2010). "Valdosta's Most Infamous Resident – John Henry 'Doc' Holliday". Valdosta Scene. VI (1): 19–20.

- ^ a b Roberts, Gary L. (2006). Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0471262919.: 407–409

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Holliday, Karen Tanner (2001). Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806133201.

- ^ Folsom, Allen. "Doc Holliday and the Swimming Hole Incident". www.valdosta.edu – Valdosta State University. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Gary L. (March 24, 2012). "Trailing an American Mythmaker: History and Glenn G. Boyer's Tombstone Vendetta". Tombstone History Archives. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Doc Holliday". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "John Henry "Doc" Holliday, D.D.S." Dodge City, Kansas: Ford County Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c Traywick, Ben. "Doc Holliday". HistoryNet. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Ballard, Susan. "Facts Any Good Doc Holliday Aficionado Should Know". Tombstone Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Erik J. Wright (December 2001). "Looking For Doc in Dallas". True West Magazine, pp. 42–43; text: "... about three blocks east of the site of today's Dealey Plaza ..."

- ^ "Doc Holliday". legendsofamerica.com. Legends of America. Archived from the original on October 24, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "The Tombstone News". thetombstonenews.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017.

- ^ Cozzone, Chris; Boggio, Jim (2013). Boxing in New Mexico, 1868–1940. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-0786468287. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c Clavin, Tom (March 27, 2017). "When Doc Met Wyatt". True West Magazine. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ "Alexander Autographs Live Auction". Archived from the original on July 12, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ "Dentistry". Dodge City Times. June 8, 1878.

- ^ a b Geringer, Joseph. "Wyatt Earp: Knight With A Six-Shooter". CrimeLibrary.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2006. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ a b Erwin, Richard (2000). The Truth About Wyatt Earp (paperback ed.). iUniverse. p. 464. ISBN 978-0595001279. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ Linder, Douglas, ed. (2005). "Testimony of Wyatt S. Earp in the Preliminary Hearing in the Earp-Holliday Case". Famous Trials: The O. K. Corral Trial. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2011. From Turner, Alford (Ed.), The O. K. Corral Inquest (1992)

- ^ "The Tombstone News". Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Cooper, David K.C., ed. (2013). Doctors of Another Calling: Physicians Who are Known Best in Fields Other Than Medicine. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1611494679. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c Monahan, Sherry (2013). Mrs. Earp (First ed.). TwoDot. ASIN B00I1LVKYA.

- ^ a b c Guinn, Jeff (May 17, 2011). The Last Gunfight: the Real Story of the Shootout at the O.K. Corral and How it Changed the American West (1st Simon & Schuster hardcover ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1439154243. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c Paula Mitchell Marks (1989). And Die in the West: the Story of the O.K. Corral Gunfight. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0671706144.[permanent dead link]

- ^ United States Reports, Supreme Court: Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Supreme Court of the United States Archived May 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (October Term, 1878), by William T. Otto, published 1879, from Harvard University

- ^ A Builder of the West: The Life of General William Jackson Palmer Archived May 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, by John Stirling Fisher and Chase Mellen, 1981, by Ayer Publishing.

- ^ a b Weiser, Kathy (March 2010). "John Joshua Webb". Legends of America. Archived from the original on March 25, 2006.

- ^ O'Neal, Bill (1979). Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806123356. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Tombstone, AZ". Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ Weir, William (2009). History's Greatest Lies: the Startling Truths Behind World Events our History Books Got Wrong. Beverly, MA: Fair Winds Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-1592333363.

- ^ a b c "Bad Hombres: Doc Holliday". Archived from the original on March 4, 2014.

- ^ Jay, Roger (October 2004). "The Gamblers' War in Tombstone". HistoryNet.com. Wild West. Archived from the original on April 6, 2011.

- ^ Traywick, Ben T. "Wyatt Earp's Thirteen Dead Men". thetombstonenews.com. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ "O.K. Corral". HistoryNet. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Urban, William L. (2003). "Tombstone". Wyatt Earp: The OK Corral and the Law of the American West. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 75. ISBN 978-0823957408.

- ^ a b Lubet, Steven (2004). Murder in Tombstone: the Forgotten Trial of Wyatt Earp. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0300115277. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ^ Linder, Douglas, ed. (2005). "Testimony of John Behan in the Preliminary Hearing in the Earp-Holliday Case". Famous Trials: The O. K. Corral Trial. Archived from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2011. From Turner, Alford (Ed.), The O. K. Corral Inquest (1992)

- ^ Tombstone Nugget; October 27, 1881

- ^ "Another Chapter in the Bloody Episode". Famous Trials. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Wyatt Earp's Vendetta Posse". HistoryNet.com. January 29, 2007. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ "Wyatt Earp's Vendetta Posse". History.net. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- ^ "Coroner's Inquest upon the body of Florentino Cruz, the murdered half-breed". Tombstone, Arizona: The Tombstone Epitaph. March 27, 1882. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Another Murder by the Earp Party". Sacramento Daily Union. March 24, 1882. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c Barra, Alan. "Who Was Wyatt Earp?". American Heritage. Archived from the original on May 7, 2006. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ Shillingberg, William B. (Summer 1976). "Wyatt Earp and the Buntline Special Myth". Kansas Historical Quarterly. 42 (2): 113–154. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Scott; Johnson, Craig. "The Earps, Doc Holliday, & The Blonger Bros". BlongerBros.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ Singer, Saul Jay (September 24, 2015). "Wyatt Earp's Mezuzah". JewishPress.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ Hornung, Chuck; Gary L., Roberts (November 1, 2001). "The Split". TrueWestMagazine.com. True West. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ a b DeArment, Robert K. (1989). Bat Masterson: The Man and the Legend. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 442. ISBN 978-0806122212.

- ^ a b "Biographical Notes Bat Masterson". Archived from the original on September 27, 2011.

- ^ "Doc Holliday – Deadly Doctor of the West". Legends of America. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016.

- ^ John Ringo Archived October 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine at thewildwest.org, retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Ortega, Tony (December 24, 1998). "How the West Was Spun". Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ Lubet, Steven (2006). Murder in Tombstone: The Forgotten Trial of Wyatt Earp. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300115277.

- ^ Ortega, Tony (March 4, 1999). "I Married Wyatt Earp". Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Tanner, KH. Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait. University of Oklahoma Press (2012), Kindle location 2213. ASIN B0099P9T8Q

- ^ Pueblo Daily Chieftain, July 19, 1882.

- ^ Tanner (2012), Kindle location 2244

- ^ a b c Kyner, James H.; As told to Hawthorne Daniel (1960). End of Track. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 240 to 243.

- ^ a b c Jay, Roger (August 14, 2006). "Spitting Lead in Leadville: Doc Holliday's Last Stand". HistoryNet. Wild West Magazine. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Glenwood Springs Timeline 1880–1889". Frontier Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ "Doc Holliday's Last Days". True West Magazine. November 1, 2001. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Neidert, Marlene (September 20, 2018). "Doc's Derringer Continues to Attract Doc Holliday History Buffs". Visit Glenwood Springs.

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze (1995). The Illustrated Life and Times of Doc Holliday (Second ed.). Phoenix: Tri Star-Boze Publications. ISBN 1887576002.

- ^ "Doc Holliday's Grave in Griffin". Atlas Obscura.

- ^ "The Natural American: Doc Holliday". Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

based on information found in The Chronicles of Tombstone by Ben Traywick

- ^ "Doc Holliday – Deadly Doctor of the West". Archived from the original on December 11, 2008.

- ^ Metzger, Jeff (2010). The Rogue's Handbook: A Concise Guide to Conduct for the Aspiring Gentleman Rogue. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks. ISBN 978-1402243653. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016.

- ^ "Interview with Virgil Earp Arizona Daily Star". Arizona Affairs. May 30, 1882. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2011. Originally published in the Arizona Daily Star on May 30, 1882

- ^ a b Paul, Lee. "John Henry Holliday". Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Wilcox, Victoria (August 11, 2015). "Doc Holliday and the Ghost of Ed Bailey |". victoriawilcoxbooks.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Rowe, Jeremy (2002). "Thoughts on Kaloma, the Purported Photograph of Josie Earp". Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ "The top ten greatest sidekicks". gulfnews.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2014.

- ^ Microsoft Encarta 2009; Doc Holliday

- ^ "Georgia Historical Markers Collection Items". dlg.usg.edu. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017 – via Digital Library of Georgia.

- ^ Miller, Susan L. (2006). Shop Tucson!. Lulu Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1430301417.

- ^ Roberts (2011, p. 247) Wyatt Earp later claimed that Doc and I were the only ones in Tucson at the time Frank Stilwell was killed

- ^ Harris, Kay (January 1, 2010). "Happy Birthday Valdosta! – City celebrates Sesquicentennial in 2010". Valdosta Scene. VI (1): 8–9.

- ^ Elizabeth Walton (March 22, 2018). "New "Doc" in town for 2nd annual Doc Holli-Days in Tombstone". KOLD News 13.

- ^ Skyways.org Archived January 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, John Henry Holliday arrives in Dodge City from Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait, by Karen Holliday Tanner, 1998

- ^ Doc Holliday's Gold Bars at IMDb

- ^ Stagecoach at IMDb

- ^ Wynonna Earp at IMDb

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (May 2017). "Jeremy Renner To Play Doc Holliday In New Biopic". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ "Winners – 2009 – Best Western Song". Western Writers of America. 2020. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Volbeat. "Volbeat | Music | Outlaw Gentlemen & Shady Ladies". Volbeat. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Civil War Premiere Music Video For Track 'Tombstone'". Metal Addicts. November 5, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Bell, Bob Boze. The Illustrated Life and Times of Doc Holliday, Phoenix: Tri-Star Boze Publications, 1994.

- DeMattos, Jack. "Gunfighters of the Real West: Doc Holliday," Real West, January 1982.

- Jahns, Pat. The Frontier World of Doc Holliday: Faro Dealer from Dallas to Deadwood, New York: Hastings House Publishers, Inc. 1957.

- Kirkpatrick, J.R. "Doc Holliday's Missing Grave." True West, October 1990.

- Lynch, Sylvia D. (1995). Aristocracy's Outlaw: The Doc Holliday Story. Tennessee Iris Press. ISBN 0964578107.

- Marks, Paula Mitchell. And Die in the West: The Story of the O.K. Corral Gunfight, New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1989 ISBN 0688072887

- Masterson, W.B. "Bat. "Famous Gun Fighters of the Western Frontier: 'Doc' Holliday," Human Life Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 2, May, 1907.

- Myers, John Myers. Doc Holliday, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1955.

- Palmquist, Robert F. "Good-Bye Old Friend," Real West, May 1979.

- Roberts, Gary L. "The Fremont Street Fiasco," True West, July 1988.

- Roberts, Gary L. (2006). Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0471262919.

- Tanner, Karen Holliday (1998). Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806133201.

- "The Life and Times of Doc Holliday". The Tombstone Epitaph. Special Historical Edition. Tombstone, AZ. 2012. ISSN 1940-221X.

External links

[edit]- John Henry Holliday family history at the Wayback Machine (archived November 12, 2017)

- Where's Doc? at the Wayback Machine (archived June 19, 2019)

- 1851 births

- 1887 deaths

- People from Griffin, Georgia

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- People from American folklore

- American gamblers

- American poker players

- Arizona folklore

- 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- People from Arizona Territory

- Gunslingers of the American Old West

- Tuberculosis deaths in Colorado

- People of the Cochise County conflict

- Film sidekicks

- People from Tombstone, Arizona

- 19th-century American dentists