The Thing (1982 film)

| The Thing | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Drew Struzan | |

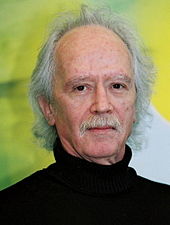

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Screenplay by | Bill Lancaster |

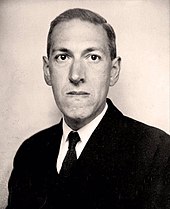

| Based on | Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | Kurt Russell |

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey |

| Edited by | Todd Ramsay |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

Production company | The Turman-Foster Company |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $19.9 million (North America)[a] |

The Thing is a 1982 American science fiction horror film directed by John Carpenter from a screenplay by Bill Lancaster. Based on the 1938 John W. Campbell Jr. novella Who Goes There?, it tells the story of a group of American researchers in Antarctica who encounter the eponymous "Thing", an extraterrestrial life-form that assimilates, then imitates, other organisms. The group is overcome by paranoia and conflict as they learn that they can no longer trust each other and that any of them could be the Thing. The film stars Kurt Russell as the team's helicopter pilot R.J. MacReady, with A. Wilford Brimley, T. K. Carter, David Clennon, Keith David, Richard Dysart, Charles Hallahan, Peter Maloney, Richard Masur, Donald Moffat, Joel Polis, and Thomas G. Waites in supporting roles.

Production began in the mid-1970s as a faithful adaptation of the novella, following 1951's The Thing from Another World. The Thing went through several directors and writers, each with different ideas on how to approach the story. Filming lasted roughly twelve weeks, beginning in August 1981, and took place on refrigerated sets in Los Angeles as well as in Juneau, Alaska, and Stewart, British Columbia. Of the film's $15 million budget, $1.5 million was spent on Rob Bottin's creature effects, a mixture of chemicals, food products, rubber, and mechanical parts turned by his large team into an alien capable of taking on any form.

The Thing was released in 1982 to negative reviews that described it as "instant junk" and "a wretched excess". Critics both praised the special effects achievements and criticized their visual repulsiveness, while others found the characterization poorly realized. The film grossed $19.6 million during its theatrical run. Many reasons have been cited for its failure to impress audiences: competition from films such as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, which offered an optimistic take on alien visitation; a summer that had been filled with successful science fiction and fantasy films; and an audience living through a recession, diametrically opposed to The Thing's nihilistic and bleak tone.

The film found an audience when released on home video and television. In the subsequent years, it has been reappraised as one of the best science fiction and horror films ever made and has gained a cult following. Filmmakers have noted its influence on their work, and it has been referred to in other media such as television and video games. The Thing has spawned a variety of merchandise – including a 1982 novelization, "haunted house" attractions, board games – and sequels in comic books, a video game of the same title, and a 2011 prequel film of the same title.

Plot

[edit]In Antarctica, a Norwegian helicopter pursues a sled dog to an American research station. The Americans witness the passenger accidentally blow up the helicopter and himself. The pilot fires a rifle and shouts at the Americans, but they cannot understand him and he is shot dead in self-defense by station commander Garry. The American helicopter pilot, R.J. MacReady, and Dr. Copper leave to investigate the Norwegian base. Among the charred ruins and frozen corpses, they find the burnt corpse of a malformed humanoid, which they transfer to the American station. Their biologist, Blair, autopsies the remains and finds a normal set of human organs.

Clark kennels the sled dog, and it soon metamorphoses and absorbs several of the station dogs. This disturbance alerts the team, and Childs uses a flamethrower to incinerate the creature. Blair autopsies the Dog-Thing and surmises it is an organism that can perfectly imitate other life forms. Data recovered from the Norwegian base leads the Americans to a large excavation site containing a partially buried alien spacecraft, which Norris estimates has been buried for over a hundred thousand years, and a smaller, human-sized dig site. Blair grows paranoid after running a computer simulation that indicates the creature could assimilate all life on Earth in a matter of years. The group implements controls to reduce the risk of assimilation.

The remains of the malformed humanoid assimilate an isolated Bennings, but Windows interrupts the process and MacReady burns the Bennings-Thing. The team also imprisons Blair in a tool shed after he sabotages all the vehicles, kills the remaining sled dogs, and destroys the radio to prevent escape. Copper suggests testing for infection by comparing the crew's blood against uncontaminated blood held in storage, but after learning the blood stores have been destroyed, the men lose faith in Garry's leadership, and MacReady takes command. He, Windows, and Nauls find Fuchs' burnt corpse and surmise he committed suicide to avoid assimilation. Windows returns to base while MacReady and Nauls investigate MacReady's shack. During their return, Nauls abandons MacReady in a snowstorm, believing he has been assimilated after finding his torn clothes in the shack.

The team debates whether to allow MacReady inside, but he breaks in and holds the group at bay with dynamite. During the encounter, Norris appears to suffer a heart attack. As Copper attempts to defibrillate Norris, his chest transforms into a large mouth and bites off Copper's arms, killing him. MacReady incinerates the Norris-Thing, but its head detaches and attempts to escape before also being burnt. MacReady hypothesizes that the Norris-Thing demonstrated that every part of the Thing is an individual life-form with its own survival instinct. He proposes testing blood samples from each survivor with a heated piece of wire and has each man restrained, but is forced to kill Clark after he lunges at MacReady with a scalpel. Everyone passes the test except Palmer, whose blood recoils from the heat. Exposed, the Palmer-Thing transforms, breaks free of its bonds, and infects Windows, forcing MacReady to incinerate them both.

Childs is left on guard while the others go to test Blair, but they find that he has escaped, and has been using vehicle components to assemble a small flying saucer, which they destroy. Upon their return, Childs is missing, and the power generator is destroyed, leaving the men without heat. MacReady speculates that, with no escape left, the Thing intends to return to hibernation until a rescue team arrives. MacReady, Garry, and Nauls agree that the Thing cannot be allowed to escape and set explosives to destroy the station, but the Blair-Thing kills Garry, and Nauls disappears. The Blair-Thing transforms into an enormous creature and breaks the detonator, but MacReady triggers the explosives with a stick of dynamite, destroying the station.

While MacReady sits by the burning remnants, Childs returns, claiming he got lost in the storm while pursuing Blair. Exhausted and slowly freezing to death, they acknowledge the futility of their distrust and share a bottle of Scotch whisky.

Cast

[edit]- Kurt Russell as R.J. MacReady, the helicopter pilot[1]

- A. Wilford Brimley as Blair, the senior biologist[2][3][4]

- T. K. Carter as Nauls, the cook[5][4]

- David Clennon as Palmer, the assistant mechanic[6]

- Keith David as Childs, the chief mechanic[3][4][6]

- Richard Dysart as Dr. Copper, the physician[3][6]

- Charles Hallahan as Norris, the geologist[6]

- Peter Maloney as George Bennings, the meteorologist[7][8]

- Richard Masur as Clark, the dog handler[4]

- Joel Polis as Fuchs, the assistant biologist[6]

- Donald Moffat as Garry, the station commander[6]

- Thomas Waites as Windows, the radio operator[6]

The Thing also features Norbert Weisser as one of the Norwegians,[9] and an uncredited dog, Jed, as the Dog-Thing.[10] The only female presence in the film is the voice of MacReady's chess computer, voiced by Carpenter's then-wife, Adrienne Barbeau.[11][12] Producer David Foster, associate producer Larry Franco, and writer Bill Lancaster, along with other members of the crew, make a cameo appearance in a recovered photograph of the Norwegian team.[13] Camera operator Ray Stella stood in for the shots where needles were used to take blood, telling Carpenter that he could do it all day. Franco also played the Norwegian wielding a rifle and hanging out of the helicopter during the opening sequence.[14][9] Stunt coordinator Dick Warlock also made a number of cameos in the film, most notably in an off-screen appearance as the shadow on the wall during the scene where the Dog-Thing enters one of the researcher's living quarters.[15] Clennon was originally intended to be in the scene, but due to his shadow being easily identifiable Carpenter decided to use Warlock instead.[16] Warlock also played Palmer-Thing and stood in for Brimley in a few scenes that involved Blair.[17]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Development of the film began in the mid-1970s when David Foster and fellow producer Lawrence Turman suggested to Universal Pictures an adaptation of the 1938 John W. Campbell novella Who Goes There?. It had been loosely adapted once before in Howard Hawks' and Christian Nyby's 1951 film The Thing from Another World, but Foster and Turman wanted to develop a project that stuck more closely to the source material. Screenwriters Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins held the rights to make an adaptation, but passed on the opportunity to make a new film, so Universal obtained the rights from them.[11][18] In 1976, Wilbur Stark had purchased the remake rights to 23 RKO Pictures films, including The Thing from Another World, from three Wall Street financiers who did not know what to do with them, in exchange for a return when the films were produced.[19] Universal in turn acquired the rights to remake the film from Stark, resulting in him being given an executive producer credit on all print advertisements, posters, television commercials, and studio press material.[20]

John Carpenter was first approached about the project in 1976 by co-producer and friend Stuart Cohen,[21] but Carpenter was mainly an independent film director, so Universal chose The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) director Tobe Hooper as they already had him under contract. The producers were ultimately unhappy with Hooper and his writing partner Kim Henkel's concept. After several more failed pitches by different writers, and attempts to bring on other directors, such as John Landis, the project was put on hold. Even so, the success of Ridley Scott's 1979 science fiction horror film Alien helped revitalize the project, at which point Carpenter became loosely attached following his success with his influential slasher film Halloween (1978).[11][22]

Carpenter was reluctant to join the project, for he thought Hawks' adaptation would be difficult to surpass, although he considered the film's monster to be unnotable. Cohen suggested that he read the original novella. Carpenter found the "creepiness" of the imitations conducted by the creature, and the questions it raised, interesting. He drew parallels between the novella and Agatha Christie's mystery novel And Then There Were None (1939), and noted that the story of Who Goes There? was "timely" for him, meaning he could make it "true to [his] day" as Hawks had in his time.[23] Carpenter, a fan of Hawks' adaptation, paid homage to it in Halloween, and he watched The Thing from Another World several times for inspiration before filming began.[24][25] Carpenter and cinematographer Dean Cundey first worked together on Halloween, and The Thing was their first big-budget project for a major film studio.[25]

After securing the writer and crew, the film was stalled again when Carpenter nearly quit, believing that a passion project of his, El Diablo (1990), was on the verge of being made by EMI Films. The producers discussed various replacements including Walter Hill, Sam Peckinpah and Michael Ritchie, but the development of El Diablo was not as imminent as Carpenter believed, and he remained with The Thing.[11]

Universal initially set a budget of $10 million, with $200,000 for "creature effects", which at the time was more than the studio had ever allocated to a monster film. Filming was scheduled to be completed within 98 days. Universal's production studios estimated that it would require at least $17 million before marketing and other costs, as the plan involved more set construction, including external sets and a large set piece for the original scripted death of Bennings, which was estimated to cost $1.5 million alone. As storyboarding and designs were finalized, the crew estimated they would need at least $750,000 for creature effects, a figure Universal executives agreed to after seeing the number of workers employed under Rob Bottin, the special make-up effects designer. Larry Franco was responsible for making the budget work for the film; he cut the filming schedule by a third, eliminated the exterior sets for on-site shooting, and removed Bennings' more extravagant death scene. Cohen suggested reusing the destroyed American camp as the ruined Norwegian camp, saving a further $250,000. When filming began in August, The Thing had a budget of $11.4 million, and indirect costs brought it to $14 million.[26] The effects budget ran over, eventually totaling $1.5 million, forcing the elimination of some scenes, including Nauls' confrontation of a creature dubbed the "box Thing".[12][26] By the end of production, Carpenter had to make a personal appeal to executive Ned Tanen for $100,000 to complete a simplified version of the Blair-Thing.[26] The final cost was $12.4 million, and overhead costs brought it to $15 million.[12][26][b]

Writing

[edit]

Several writers developed drafts for The Thing before Carpenter became involved, including Logan's Run (1967) writer William F. Nolan, novelist David Wiltse, and Hooper and Henkel, whose draft was set at least partially underwater, and which Cohen described as a Moby-Dick-like story in which "The Captain" did battle with a large, non-shapeshifting creature.[11] As Carpenter said in a 2014 interview, "they were just trying to make it work".[27] The writers left before Carpenter joined the project.[27][28][29] He said the scripts were "awful", as they changed the story into something it was not, and ignored the chameleon-like aspect of the Thing.[21] Carpenter did not want to write the project himself, after recently completing work on Escape from New York (1981), and having struggled to complete a screenplay for The Philadelphia Experiment (1984). He was wary of taking on writing duties, preferring to let someone else do it.[23] Once Carpenter was confirmed as the director, several writers were asked to script The Thing, including Richard Matheson, Nigel Kneale, and Deric Washburn.[11]

Bill Lancaster initially met with Turman, Foster and Cohen in 1977, but he was given the impression that they wanted to closely replicate The Thing from Another World, and he did not want to remake the film.[30] In August 1979, Lancaster was contacted again. By this time he had read the original Who Goes There? novella, and Carpenter had become involved in the project.[30] Lancaster was hired to write the script after describing his vision for the film, and his intention to stick closely to the original story, to Carpenter, who was a fan of Lancaster's work on The Bad News Bears (1976).[23][30][29] Lancaster conceived several key scenes in the film, including the Norris-Thing biting Dr. Copper, and the use of blood tests to identify the Thing, which Carpenter cited as the reason he wanted to work on the film.[23] Lancaster said he found some difficulty in translating Who Goes There? to film, as it features very little action. He also made some significant changes to the story, such as reducing the number of characters from 37 to 12. Lancaster said that 37 was excessive and would be difficult for audiences to follow, leaving little screen time for characterization. He also opted to alter the story's structure, choosing to open his in the middle of the action, instead of using a flashback as in the novella.[30] Several characters were modernized for contemporary audiences; MacReady, originally a meteorologist, became a tough loner described in the script as "35. Helicopter pilot. Likes chess. Hates the cold. The pay is good." Lancaster aimed to create an ensemble piece where one person emerged as the hero, instead of having a Doc Savage-type hero from the start.[31]

Lancaster wrote thirty to forty pages but struggled with the film's second act, and it took him several months to complete the script.[23][30] After it was finished, Lancaster and Carpenter spent a weekend in northern California refining the script, each having different takes on how a character should sound, and comparing their ideas for scenes. Lancaster's script opted to keep the creature largely concealed throughout the film, and it was Bottin who convinced Carpenter to make it more visible to have a greater impact on the audience.[23][32] Lancaster's original ending had both MacReady and Childs turn into the Thing. In the spring, the characters are rescued by helicopter, greeting their saviors with "Hey, which way to a hot meal?". Carpenter thought this ending was too shallow. In total, Lancaster completed four drafts of the screenplay. The novella concludes with the humans clearly victorious, but concerned that birds they see flying toward the mainland may have been infected by the Thing. Carpenter opted to end the film with the survivors slowly freezing to death to save humanity from infection, believing this to be the ultimate heroic act.[23][33] Lancaster wrote this ending, which eschews a The Twilight Zone-style twist or the destruction of the monster, as he wanted to instead have an ambiguous moment between the pair, of trust and mistrust, fear and relief.[34]

Casting

[edit]

Anita Dann served as casting director.[36] Kurt Russell had worked with Carpenter twice before and was involved in the production before being cast, helping Carpenter develop his ideas.[37] Russell was the last actor to be cast, in June 1981, by which point second unit filming was starting in Juneau, Alaska.[37][38] Carpenter wanted to keep his options open for the lead R.J. MacReady, and discussions with the studio considered Christopher Walken, Jeff Bridges, and Nick Nolte, who were either unavailable or declined, and Sam Shepard, who showed interest but was never pursued. Tom Atkins and Jack Thompson were strong early and late contenders for the role of MacReady, but the decision was ultimately made to go with Russell.[38] In part, Carpenter cited the practicality of choosing someone he had found reliable before, and who would not balk at the difficult filming conditions.[39] It took Russell about a year to grow his hair and beard out for the role.[14] At various points, the producers also met with Brian Dennehy, Kris Kristofferson, John Heard, Ed Harris, Tom Berenger, Jack Thompson, Scott Glenn, Fred Ward, Peter Coyote, Tom Atkins, and Tim McIntire. Some passed on the idea of starring in a monster film, while Dennehy became the choice to play Copper.[38] Each actor was to be paid $50,000, but after the more-established Russell was cast, his salary increased to $400,000.[26]

Geoffrey Holder, Carl Weathers, and Bernie Casey were considered for the role of mechanic Childs, and Carpenter also looked at Isaac Hayes, having worked with him on Escape from New York. Ernie Hudson was the front-runner and was almost cast until they met with Keith David.[40] The Thing was David's first significant film role, and coming from a theater background, he had to learn on set how to hold himself back and not show every emotion his character was feeling, with guidance from Richard Masur and Donald Moffat in particular. Masur (dog handler Clark) and David discussed their characters in rehearsals and decided that they would not like each other.[36] For senior biologist Blair, the team chose the then-unknown Wilford Brimley, as they wanted an everyman whose absence would not be questioned by the audience until the appropriate time. The intent with the character was to have him become infected early in the film but offscreen, so that his status would be unknown to the audience, concealing his intentions. Carpenter wanted to cast Donald Pleasence, but it was decided that he was too recognizable to accommodate the role.[35] T. K. Carter was cast as the station's cook Nauls, but comedian Franklyn Ajaye also came in to read for the role. Instead, he delivered a lengthy speech about the character being a stereotype, after which the meeting ended.[41]

Bottin lobbied hard to play assistant mechanic Palmer, but it was deemed impossible for him to do so alongside his existing duties. As the character has some comedic moments, Universal brought in comedians Jay Leno, Garry Shandling, and Charles Fleischer, among others, but opted to go with actor David Clennon, who was better suited to play the dramatic elements.[42] Clennon had read for the Bennings character, but he preferred Palmer's "blue-collar stoner" role to a "white collar science man".[36] Powers Boothe,[11] Lee Van Cleef, Jerry Orbach, and Kevin Conway were considered for the role of station commander Garry, and Richard Mulligan was also considered when the production experimented with the idea of making the character closer to MacReady in age.[43] Masur also read for Garry, but he asked to play the dog handler Clark instead, as he liked the character's dialogue and was also a fan of dogs. Masur worked daily with the wolfdog Jed and his handler, Clint Rowe, during rehearsals, as Rowe was familiarizing Jed with the sounds and smells of people. This helped Masur's and Jed's performance onscreen, as the dog would stand next to him without looking for his handler. Masur described his character as one uninterested in people, but who loves working with dogs. He went to a survivalist store and bought a flip knife for his character, and used it in a confrontation with David's character.[36] Masur turned down a role in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial to play Clark.[44] William Daniels and Dennehy were both interested in playing Dr. Copper, and it was a last-second decision by Carpenter to go with Richard Dysart.[43]

In early drafts, Windows was called Sanchez, and later Sanders. The name Windows came when the actor for the role, Thomas Waites, was in a costume fitting and tried on a large pair of dark glasses, which the character wears in the film.[45] Russell described the all-male story as interesting since the men had no one to posture for without women.[37]

Filming

[edit]The Thing was storyboarded extensively by Mike Ploog and Mentor Huebner before filming began. Their work was so detailed that many of the film's shots replicate the image layout completely.[46] Cundey pushed for the use of anamorphic format aspect ratio, believing that it allowed for placing several actors in an environment, and making use of the scenic vistas available, while still creating a sense of confinement within the image. It also enabled the use of negative space around the actors to imply something may be lurking just offscreen.[14]

Principal photography began on August 24, 1981, in Juneau, Alaska.[12][47] Filming lasted about twelve weeks.[48] Carpenter insisted on two weeks of rehearsals before filming as he wanted to see how scenes would play out. This was unusual at the time because of the expense involved.[34] Filming then moved to the Universal lot, where the outside heat was over 100 °F (38 °C). The internal sets were climate-controlled to 28 °F (−2 °C) to facilitate their work.[37][47] The team considered building the sets inside an existing refrigerated structure but were unable to find one large enough. Instead, they collected as many portable air conditioners as they could, closed off the stage, and used humidifiers and misters to add moisture to the air.[49] After watching a roughly assembled cut of filming to date, Carpenter was unhappy that the film seemed to feature too many scenes of men standing around talking. He rewrote some already completed scenes to take place outdoors to be shot on location when principal photography moved to Stewart, British Columbia.[25][36]

Carpenter was determined to use authentic locations instead of studio sets, and his successes on Halloween and The Fog (1980) gave him the credibility to take on the much bigger-budget production of The Thing. A film scout located an area just outside Stewart, along the Canadian coast, which offered the project both ease of access and scenic value during the day.[25] On December 2, 1981, roughly 100 American and Canadian crew members moved to the area to begin filming.[48] During the journey there, the crew bus slid in the snow toward the unprotected edge of the road, nearly sending it down a 500-foot (150 m) embankment.[44] Some of the crew stayed in the small mining town during filming, while others lived on residential barges on the Portland Canal.[36] They would make the 27-mile (43 km) drive up a small, winding road to the filming location in Alaska where the exterior outpost sets were built.[37][36][50]

The sets had been built in Alaska during the summer, atop a rocky area overlooking a glacier, in preparation for snow to fall and cover them.[25] They were used for both interior and exterior filming, meaning they could not be heated above freezing inside to ensure there was always snow on the roof. Outside, the temperature was so low that the camera lenses would freeze and break.[37] The crew had to leave the cameras in the freezing temperatures, as keeping them inside in the warmth resulted in foggy lenses that took hours to clear.[47] Filming, greatly dependent on the weather, took three weeks to complete,[49] with heavy snow making it impossible to film on some days.[36] Rigging the explosives necessary to destroy the set in the film's finale required 8 hours.[51]

Keith David broke his hand in a car accident the day before he was to begin shooting. David attended filming the next day, but when Carpenter and Franco saw his swollen hand, they sent him to the hospital where it was punctured with two pins. He returned wearing a surgical glove beneath a black glove that was painted to resemble his complexion. His left hand is not seen for the first half of the film.[36] Carpenter filmed the Norwegian camp scenes after the end scenes, using the damaged American base as a stand-in for the charred Norwegian camp.[52] The explosive destruction of the base required the camera assistants to stand inside the set with the explosives, which were activated remotely. The assistants then had to run to a safe distance while seven cameras captured the base's destruction.[51] Filmed when the heavy use of special effects was rare, the actors had to adapt to having Carpenter describe to them what their characters were looking at, as the effects would not be added until post-production. There were some puppets used to create the impression of what was happening in the scene, but in other cases, the cast would be looking at a wall or an object marked with an X.[37]

Art director John J. Lloyd oversaw the design and construction of all the sets, as there were no existing locations used in the film.[49] Cundey suggested that the sets should have ceilings and pipes seen on camera to make the spaces seem more claustrophobic.[49]

Post-production

[edit]Several scenes in the script were omitted from the film, sometimes because there was too much dialogue that slowed the pace and undermined the suspense. Carpenter blamed some of the issues on his directorial method, noting that several scenes appeared to be repeating events or information. Another scene featuring a snowmobile chase pursuing dogs was removed from the shooting script as it would have been too expensive to film. One scene present in the film, but not the script, features a monologue by MacReady. Carpenter added this partly to establish what was happening in the story and because he wanted to highlight Russell's heroic character after taking over the camp. Carpenter said that Lancaster's experience writing ensemble pieces did not emphasize single characters. Since Halloween, several horror films had replicated many of the scare elements of that film, something Carpenter wanted to move away from for The Thing. He removed scenes from Lancaster's script that had been filmed, such as a body suddenly falling into view at the Norwegian camp, which he felt were too clichéd.[23] Approximately three minutes of scenes were filmed from Lancaster's script that elaborated on the characters' backgrounds.[36]

A scene with MacReady absentmindedly inflating a blow-up doll while watching the Norwegian tapes was filmed but was not used in the finished film. The doll would later appear as a jump scare with Nauls. Other scenes featured expanded or alternate deaths for various characters. In the finished film, Fuchs' charred bones are discovered, revealing he has died offscreen, but an alternate take sees his corpse impaled on a wall with a shovel. Nauls was scripted to appear in the finale as a partly assimilated mass of tentacles, but in the film, he simply disappears.[53] Carpenter struggled with a method of conveying to the audience what assimilation by the creature actually meant. Lancaster's original set piece of Bennings' death had him pulled beneath a sheet of ice by the Thing, before resurfacing in different areas in various stages of assimilation. The scene called for a set to be built on one of Universal's largest stages, with sophisticated hydraulics, dogs, and flamethrowers, but it was deemed too costly to produce.[54] A scene was filmed with Bennings being murdered by an unknown assailant, but it was felt that assimilation, leading to his death, was not explained enough. Short on time, and with no interior sets remaining, a small set was built, Maloney was covered with K-Y Jelly, orange dye, and rubber tentacles. Monster gloves for a different creature were repurposed to demonstrate partial assimilation.[53][54]

Carpenter filmed multiple endings for The Thing, including a "happier" ending because editor Todd Ramsay thought that the bleak, nihilistic conclusion would not test well with audiences. In the alternate take, MacReady is rescued and given a blood test that proves he is not infected.[52][55] Carpenter said that stylistically this ending would have been "cheesy".[23] Editor Verna Fields was tasked with reworking the ending to add clarity and resolution. It was finally decided to create an entirely new scene, which omitted the suspicion of Childs being infected by removing him completely, leaving MacReady alone.[23] This new ending tested only slightly better with audiences than the original, and the production team agreed to the studio's request to use it.[56][57] It was set to go to print for theaters when the producers, Carpenter, and executive Helena Hacker decided that the film was better left with ambiguity instead of nothing at all. Carpenter gave his approval to restore the ambiguous ending, but a scream was inserted over the outpost explosion to posit the monster's death.[23][56] Universal executive Sidney Sheinberg disliked the ending's nihilism and, according to Carpenter, said, "Think about how the audience will react if we see the [Thing] die with a giant orchestra playing".[23][57] Carpenter later noted that both the original ending and the ending without Childs tested poorly with audiences, which he interpreted as the film simply not being heroic enough.[23]

Music

[edit]Ennio Morricone composed the film's score, as Carpenter wanted The Thing to have a European musical approach.[58][59] Carpenter flew to Rome to speak with Morricone to convince him to take the job. By the time Morricone flew to Los Angeles to record the score, he had already developed a tape filled with an array of synthesizer music because he was unsure what type of score Carpenter wanted.[60] Morricone wrote complete separate orchestral and synthesizer scores and a combined score, which he knew was Carpenter's preference.[61] Carpenter picked a piece, closely resembling his own scores, that became the main theme used throughout the film.[60] He also played the score from Escape from New York for Morricone as an example. Morricone made several more attempts, bringing the score closer to Carpenter's own style of music.[58] In total, Morricone produced a score of approximately one hour that remained largely unused but was later released as part of the film's soundtrack.[62] Carpenter and his longtime collaborator Alan Howarth separately developed some synth-styled pieces used in the film.[63] In 2012, Morricone recalled:

I've asked [Carpenter], as he was preparing some electronic music with an assistant to edit on the film, "Why did you call me, if you want to do it on your own?" He surprised me, he said – "I got married to your music. This is why I've called you." ... Then when he showed me the film, later when I wrote the music, we didn't exchange ideas. He ran away, nearly ashamed of showing it to me. I wrote the music on my own without his advice. Naturally, as I had become quite clever since 1982, I've written several scores relating to my life. And I had written one, which was electronic music. And [Carpenter] took the electronic score.[58]

Carpenter said:

[Morricone] did all the orchestrations and recorded for me 20 minutes of music I could use wherever I wished but without seeing any footage. I cut his music into the film and realized that there were places, mostly scenes of tension, in which his music would not work ... I secretly ran off and recorded in a couple of days a few pieces to use. My pieces were very simple electronic pieces – it was almost tones. It was not really music at all but just background sounds, something today you might even consider as sound effects.[58]

Design

[edit]Creature effects

[edit]The Thing's special effects were largely designed by Bottin,[32] who had previously worked with Carpenter on The Fog (1980).[64] When Bottin joined the project in mid-1981, pre-production was in progress, but no design had been settled on for the alien.[64] Artist Dale Kuipers had created some preliminary paintings of the creature's look, but he left the project after being hospitalized following a traffic accident before he could develop them further with Bottin.[12][64] Carpenter conceived the Thing as a single creature, but Bottin suggested that it should be constantly changing and able to look like anything.[28] Carpenter initially considered Bottin's description of his ideas as "too weird", and had him work with Ploog to sketch them instead.[64] As part of the Thing's design, it was agreed anyone assimilated by it would be a perfect imitation and would not know they were the Thing.[14] The actors spent hours during rehearsals discussing whether they would know they were the Thing when taken over. Clennon said that it did not matter, because everyone acted, looked and smelled exactly the same before (or after) being taken over.[36] At its peak, Bottin had a 35-person crew of artists and technicians, and he found it difficult to work with so many people. To help manage the team, he hired Erik Jensen, a special effects line producer who he had worked with on The Howling (1981), to be in charge of the special make-up effects unit.[65] Bottin's crew also included mechanical aspect supervisor Dave Kelsey, make-up aspect coordinator Ken Diaz, moldmaker Gunnar Ferdinansen, and Bottin's longtime friend Margaret Beserra, who managed painting and hair work.[65]

In designing the Thing's different forms, Bottin explained that the creature had been all over the galaxy. This allowed it to call on different attributes as necessary, such as stomachs that transform into giant mouths and spider legs sprouting from heads.[32] Bottin said the pressure he experienced caused him to dream about working on designs, some of which he would take note of after waking.[64] One abandoned idea included a series of dead baby monsters, which was deemed "too gross".[12] Bottin admitted he had no idea how his designs would be implemented practically, but Carpenter did not reject them. Carpenter said, "What I didn't want to end up with in this movie was a guy in a suit ... I grew up as a kid watching science-fiction monster movies, and it was always a guy in a suit."[55] According to Cundey, Bottin was very sensitive about his designs, and worried about the film showing too many of them.[52] At one point, as a preemptive move against any censorship, Bottin suggested making the creature's violent transformations and the appearance of the internal organs more fantastical using colors. The decision was made to tone down the color of the blood and viscera, although much of the filming had been completed by that point.[28] The creature effects used a variety of materials including mayonnaise, creamed corn, microwaved bubble gum, and K-Y Jelly.[24]

During filming, then-21-year-old Bottin was hospitalized for exhaustion, double pneumonia, and a bleeding ulcer, caused by his extensive workload. Bottin himself explained he would "hoard the work", opting to be directly involved in many of the complicated tasks.[66] His dedication to the project saw him spend over a year living on the Universal lot. Bottin said he did not take a day off during that time and slept on the sets or in locker rooms.[12] To take some pressure off his crew, Bottin enlisted the aid of special effects creator Stan Winston to complete some of the designs, primarily the Dog-Thing.[52][65] With insufficient time to create a sophisticated mechanical creature, Winston opted to create a hand puppet. A cast was made of makeup artist Lance Anderson's arm and head, around which the Dog-Thing was sculpted in oil-based clay. The final foam-latex puppet, worn by Anderson, featured radio-controlled eyes and cable-controlled legs,[67] and was operated from below a raised set on which the kennel was built.[67][25] Slime from the puppet would leak onto Anderson during the two days it took to film the scene, and he had to wear a helmet to protect himself from the explosive squibs simulating gunfire. Anderson pulled the tentacles into the Dog-Thing and reverse motion was used to create the effect of them slithering from its body.[67] Winston refused to be credited for his work, insisting that Bottin deserved sole credit; Winston was given a "thank you" in the credits instead.[52][65]

In the "chest chomp" scene, Dr. Copper attempts to revive Norris with a defibrillator. Revealing himself as the Thing, Norris-Thing's chest transforms into a large mouth that severs Copper's arms. Bottin accomplished this scene by recruiting a double amputee and fitting him with prosthetic arms filled with wax bones, rubber veins and Jell-O. The arms were then placed into the practical "stomach mouth" where the mechanical jaws clamped down on them, at which point the actor pulled away, severing the false arms.[52] The effect of the Norris-Thing's head detaching from the body to save itself took many months of testing before Bottin was satisfied enough to film it. The scene involved a fire effect, but the crew were unaware that fumes from the rubber foam chemicals inside the puppet were flammable. The fire ignited the fumes, creating a large fireball that engulfed the puppet. It suffered only minimal damage after the fire had been put out, and the crew successfully filmed the scene.[44][68] Stop-motion expert Randall William Cook developed a sequence for the end of the film where MacReady is confronted by the gigantic Blair-Thing. Cook created a miniature model of the set and filmed wide-angle shots of the monster in stop motion, but Carpenter was not convinced by the effect and used only a few seconds of it.[52] It took fifty people to operate the actual Blair-Thing puppet.[14]

The production intended to use a camera centrifuge – a rotating drum with a fixed camera platform – for the Palmer-Thing scene, allowing him to seem to run straight up the wall and across the ceiling. Again, the cost was too high and the idea abandoned for a stuntman falling into frame onto a floor made to look like the outpost's ceiling.[69] Stuntman Anthony Cecere stood in for the Palmer-Thing after MacReady sets it on fire and it crashes through the outpost wall.[70]

Visuals and lighting

[edit]Cundey worked with Bottin to determine the appropriate lighting for each creature. He wanted to show off Bottin's work because of its details, but he was conscious that showing too much would reveal its artificial nature, breaking the illusion. Each encounter with the creature was planned for areas where they could justify using a series of small lights to highlight the particular creature-model's surface and textures. Cundey would illuminate the area behind the creature to detail its overall shape. He worked with Panavision and a few other companies to develop a camera capable of automatically adjusting light exposure at different film speeds. He wanted to try filming the creature at fast and slow speeds thinking this would create a more interesting visual effect, but they were unable to accomplish this at the time. For the rest of the set, Cundey created a contrast by lighting the interiors with warmer lights hung overhead in conical shades so that they could still control the lighting and have darkened areas on set. The outside was constantly bathed in a cold, blue light that Cundey had discovered being used on airport runways. The reflective surface of the snow and the blue light helped create the impression of coldness.[25] The team also made use of the flamethrowers and magenta-hued flares used by the actors to create dynamic lighting.[25]

The team originally wanted to shoot the film in black-and-white, but Universal was reluctant as it could affect their ability to sell the television rights for the film. Instead, Cundey suggested muting the colors as much as possible. The inside of the sets were painted in neutral colors such as gray, and many of the props were also painted gray, while the costumes were a mix of somber browns, blues, and grays. They relied on the lighting to add color.[49] Albert Whitlock provided matte-painted backdrops, including the scene in which the Americans discover the giant alien spaceship buried in the ice.[25] A scene where MacReady walks up to a hole in the ice where the alien had been buried was filmed at Universal, while the surrounding area, including the alien spaceship, helicopter, and snow, were all painted.[14]

Carpenter's friend John Wash, who developed the opening computer simulation for Escape from New York, used a Cromemco Z-2 to design the computer program showing how the Thing assimilates other organisms. Colors were added by placing filters in front of an animation camera used to shoot the computer frames.[14][71] Model maker Susan Turner built the alien ship approaching Earth in the pre-credits sequence, which featured 144 strobing lights.[72] Drew Struzan designed the film's poster. He completed it in 24 hours, based only on a briefing, knowing little about the film.[73]

Release

[edit]Marketing

[edit]

The lack of information about the film's special effects drew the attention of film exhibitors in early 1982. They wanted reassurance that The Thing was a first-rate production capable of attracting audiences. Cohen and Foster, with a specially employed editor and Universal's archive of music, put together a 20-minute showreel emphasizing action and suspense. They used available footage, including alternate and extended scenes not in the finished film, but avoided revealing the special effects as much as possible. The reaction from the exclusively male exhibitors was generally positive, and Universal executive Robert Rehme told Cohen that the studio was counting on The Thing's success, as they expected E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial to appeal only to children.[74] While finalizing the film, Universal sent Carpenter a demographic study showing that the audience appeal of horror films had declined by seventy percent over the previous six months. Carpenter considered this a suggestion that he lower his expectations of the film's performance.[28] After one market research screening, Carpenter queried the audience on their thoughts, and one audience member asked, "Well what happened in the very end? Which one was the Thing ...?" When Carpenter responded that it was up to their imagination, the audience member responded, "Oh, God. I hate that."[23]

After returning from a screening of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, the audience's silence at a trailer of The Thing caused Foster to remark, "We're dead".[75] The response to public pre-screenings of The Thing resulted in the studio changing the somber, black-and-white advertising approved by the producers to a color image of a person with a glowing face. The tagline was also changed from "Man is the warmest place to hide" – written by Stephen Frankfort, who wrote the Alien tagline, "In space, no one can hear you scream" – to "The ultimate in alien terror", trying to capitalize on Alien's audience. Carpenter attempted to make a last-minute change of the film's title to Who Goes There?, to no avail.[75] The week before its release, Carpenter promoted the film with clips on Late Night with David Letterman.[76] In 1981, horror magazine Fangoria held a contest encouraging readers to submit drawings of what the Thing would look like. Winners were rewarded with a trip to Universal Studios.[44] On its opening day, a special screening was held at the Hollywood Pacific Theatre, presided over by Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, with free admission for those in costume as monsters.[75]

Box office

[edit]The Thing was released in the United States on June 25, 1982.[12] During its opening weekend, the film earned $3.1 million from 840 theaters – an average of $3,699 per theater – finishing as the number eight film of the weekend behind supernatural horror Poltergeist ($4.1 million), which was in its fourth weekend of release, and ahead of action film Megaforce ($2.3 million).[77][78] It dropped out of the top 10 grossing films after three weeks,[79] and ended its run earning a total of $19.6 million against its $15 million budget, making it only the 42nd highest-grossing film of 1982.[c][55][77][80] It was not a box office failure, nor was it a hit.[81] Subsequent theatrical releases have raised the box office gross to $19.9 million as of 2023[update].[82]

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]I take every failure hard. The one I took the hardest was The Thing. My career would have been different if that had been a big hit ... The movie was hated. Even by science-fiction fans. They thought that I had betrayed some kind of trust, and the piling on was insane. Even the original movie's director, Christian Nyby, was dissing me.

— John Carpenter in 2008 on the contemporary reception of The Thing[83]

The film received negative reviews on its release, and hostility for its cynical, anti-authoritarian tone and graphic special effects.[84][85] Some reviewers were dismissive of the film, calling it the "quintessential moron movie of the 80's", "instant junk",[9] and a "wretched excess".[86] Starlog's Alan Spencer called it a "cold and sterile" horror movie attempting to cash in on the genre audience, against the "optimism of E.T., the reassuring return of Star Trek II, the technical perfection of Tron, and the sheer integrity of Blade Runner".[87]

The plot was criticized as "boring",[88] and undermined by the special effects.[89] The Los Angeles Times' Linda Gross said that The Thing was "bereft, despairing, and nihilistic", and lacking in feeling, meaning the characters' deaths did not matter.[90] Spencer said it featured sloppy continuity, lacked pacing, and was devoid of warmth or humanity.[87] David Ansen of Newsweek felt the film confused the use of effects with creating suspense, and that it lacked drama by "sacrificing everything at the altar of gore".[89] The Chicago Reader's Dave Kehr considered the dialogue to be banal and interchangeable, making the characters seem and sound alike.[91] The Washington Post's Gary Arnold said it was a witty touch to open with the Thing having already overcome the Norwegian base, defeating the type of traps seen in the 1951 version,[86] while New York's David Denby lamented that the Thing's threat is shown only externally, without focusing on what it is like for someone who thinks they have been taken over.[88] Roger Ebert considered the film to be scary, but offering nothing original beyond the special effects,[92] while The New York Times' Vincent Canby said it was entertaining only if the viewer needed to see spider-legged heads and dog autopsies.[9]

Reviews of the actors' performances were generally positive,[93][87] while criticizing the depictions of the characters they portrayed.[92][94][89] Ebert said they lacked characterization, offering basic stereotypes that existed just to be killed, and Spencer called the characters bland even though the actors do the best they can with the material.[92][87] Time's Richard Schickel singled Russell out as the "stalwart" hero, where other characters were not as strongly or wittily characterized,[93] and Variety said that Russell's heroic status was undercut by the "suicidal" attitude adopted toward the film's finale.[94] Other reviews criticized implausibilities such as characters wandering off alone.[92] Kehr did not like that the men did not band together against the Thing, and several reviews noted a lack of camaraderie and romance, which Arnold said reduced any interest beyond the special effects.[89][86][91]

The film's special effects were simultaneously lauded and lambasted for being technically brilliant but visually repulsive and excessive.[88][93][86] Cinefantastique wrote that the Thing "may be the most unloved monster in movie history ... but it's also the most incredible display of special effects makeup in at least a decade."[95] Reviews called Bottin's work "genius",[88][87] noting the designs were novel, unforgettable, "colorfully horrific", and called him a "master of the macabre".[93][86] Arnold said that the "chest chomp" scene demonstrated "appalling creativity" and the subsequent severed head scene was "madly macabre", comparing them to Alien's chest burster and severed head scenes.[86] Variety called it "the most vividly gruesome horror film to ever stalk the screens".[94] Conversely, Denby called them more disgusting than frightening and lamented that the trend of horror films to open the human body more and more bordered on obscenity.[88] Spencer said that Bottin's care and pride in his craft were shown in the effects, but both they and Schickel found them to be overwhelming and "squandered" without strong characters and story.[93][87] Even so, Canby said that the effects were too "phony looking to be disgusting".[9] Canby and Arnold said the creature's lack of a single, discernible shape was to its detriment, and hiding it inside humans made it hard to follow. Arnold said that the 1951 version was less versatile but easier to keep in focus.[86][9]

Gross and Spencer praised the film's technical achievements, particularly Cundey's "frostbitten" cinematography, the sound, editing, and Morricone's score.[90][87] Spencer was critical of Carpenter's direction, saying it was his "futile" attempt to give the audience what he thinks they want and that Carpenter was not meant to direct science fiction, but was instead suited to direct "traffic accidents, train wrecks, and public floggings".[87] Ansen said that "atrocity for atrocity's sake" was ill-becoming of Carpenter.[89]

The Thing was often compared to similar films, particularly Alien, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), and The Thing from Another World.[92][88][9] Ebert and Denby said that The Thing seemed derivative compared to those films, which had portrayed the story in a better way.[92][88] Variety called it inferior to the 1951 version.[94] Arnold considered The Thing as the result of Alien raising the requirement for horrific spectacle.[86]

The Thing from Another World actor Kenneth Tobey and director Christian Nyby also criticized the film. Nyby said, "If you want blood, go to the slaughterhouse ... All in all, it's a terrific commercial for J&B Scotch".[44] Tobey singled out the visual effects, saying they "were so explicit that they actually destroyed how you were supposed to feel about the characters ... They became almost a movie in themselves, and were a little too horrifying."[81] In Phil Hardy's 1984 book Science Fiction, a reviewer described the film as a "surprising failure" and called it "Carpenter's most unsatisfying film to date".[96] The review noted that the narrative "seems little more than an excuse for the various set-pieces of special effects and Russell's hero is no more than a cypher compared to Tobey's rounded character in Howard Hawks' The Thing".[96] Clennon said that introductory scenes for the characters, omitted from the film, made it hard for audiences to connect with them, robbing it of some of the broader appeal of Alien.[36]

Accolades

[edit]The Thing received nominations from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films for Best Horror Film and Best Special Effects,[97] but lost to Poltergeist and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, respectively.[98] The film was nominated at the Razzie Awards for Worst Musical Score.[99]

Post-release

[edit]Performance analysis and aftermath

[edit]In a 1999 interview, Carpenter said audiences rejected The Thing for its nihilistic, depressing viewpoint at a time when the United States was in the midst of a recession.[23] When it opened, it was competing against the critically and commercially successful E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial ($619 million), a family-friendly film released two weeks earlier that offered a more optimistic take on alien visitation.[14][100][101] Carpenter described it as the complete opposite of his film.[44] The Thing opened on the same day as the science fiction film Blade Runner, which debuted as the number two film that weekend with a take of $6.1 million and went on to earn $33.8 million.[78][102] It was also regarded as a critical and commercial failure at the time.[81] Others blamed an oversaturation of science fiction and fantasy films released that year, including Conan the Barbarian ($130 million), Poltergeist ($121.7 million), Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan ($97 million), Mad Max 2 ($34.5 million), and Tron ($33 million). Some analysts blamed Universal's poor marketing, which did not compete with the deluge of promotion for prominent films released that summer.[81][101][103] Another factor was the R rating it was given, restricting the audience to those over the age of 17 unless accompanied by an adult. In contrast, Poltergeist, another horror film, received a PG rating, allowing families and younger children to view it.[81]

The impact on Carpenter was immediate – he lost the job of directing the 1984 science fiction horror film Firestarter because of The Thing's poor performance.[104] His previous success had gained him a multiple-film contract at Universal, but the studio opted to buy him out of it instead.[105] He continued making films afterward but lost confidence, and did not openly talk about The Thing's failure until a 1985 interview with Starlog, where he said, "I was called 'a pornographer of violence' ... I had no idea it would be received that way ... The Thing was just too strong for that time. I knew it was going to be strong, but I didn't think it would be too strong ... I didn't take the public's taste into consideration."[81] Shortly after its release, Wilbur Stark sued Universal for $43 million for "slander, breach of contract, fraud and deceit", alleging he incurred a financial loss by Universal failing to credit him properly in its marketing and by showing his name during the end credits, a less prestigious position.[19] Stark also said that he "contributed greatly to the [screenplay]".[106] David Foster responded that Stark was not involved with the film's production in any way, and received proper credit in all materials.[107] Stark later sued for a further $15 million over Foster's comments. The outcome of the lawsuits is unknown.[108]

Home media

[edit]While The Thing was not initially successful, it was able to find new audiences and appreciation on home video, and later on television.[109] Sidney Sheinberg edited a version of the film for network television broadcast, which added narration and a different ending, where the Thing imitates a dog and escapes the ruined camp. Carpenter disowned this version, and theorized that Sheinberg had been mad at him for not taking his creative ideas on board for the theatrical cut.[110][111][112]

The Thing was released on DVD in 1998 and featured additional content, such as The Thing: Terror Takes Shape – a detailed documentary on the production, deleted and alternate scenes, and commentary by Carpenter and Russell.[113][114] An HD DVD version followed in 2006 containing the same features,[115][116] and a Blu-ray version in 2008 featuring just the Carpenter and Russell commentary, and some behind-the-scenes videos available via picture-in-picture during the film.[117][118] A 2016 Blu-ray release featured a 2K resolution restoration of the film, overseen by Dean Cundey. As well as including previous features such as the commentary and Terror Takes Shape, it added interviews with the cast and crew, and segments that focus on the music, writing, editing, Ploog's artwork, an interview with Alan Dean Foster, who wrote the film's novelization, and the television broadcast version of The Thing that runs fifteen minutes shorter than the theatrical cut.[119] A 4K resolution restoration was released in 2017 on Blu-ray, initially as a United Kingdom exclusive with a limited run of eight thousand units. The restoration was created using the original film negative, and was overseen by Carpenter and Cundey.[120] A 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray was released in September 2021.[121]

MCA released the soundtrack for The Thing in 1982.[122] Varèse Sarabande re-released it in 1991 on compact disc and Compact Cassette.[123] These versions eventually ceased being manufactured. In 2011, Howarth and Larry Hopkins restored Morricone's score using updated digital techniques and arranged each track in the order it appears in the film. The album also includes tracks composed by Carpenter and Howarth for the film.[124] A remastered version of the score was released on vinyl on February 23, 2017; a deluxe edition included an exclusive interview with Carpenter.[125] In May 2020, an extended play (EP), Lost Cues: The Thing, was released. The EP contains Carpenter's contributions to The Thing's score; he re-recorded the music because the original masterings were lost.[126]

Other media

[edit]A novelization of the film was published by Alan Dean Foster in 1982.[119] It is based on an earlier draft of the script and features some differences from the finished film.[127] A scene in which MacReady, Bennings, and Childs chase infected dogs out into the snow is included,[128] and Nauls' disappearance is explained: Cornered by the Blair-Thing, he chooses suicide over assimilation.[129]

In 2000, McFarlane Toys released two "Movie Maniacs" figures: the Blair-Thing[130] and the Norris-Thing, including its spider-legged, disembodied head.[131] SOTA Toys released a set featuring a MacReady figure and the Dog-Thing based on the film's kennel scene,[132] as well as a bust of the Norris-Thing's spider-head.[133] In 2017, Mondo and the Project Raygun division of USAopoly released The Thing: Infection at Outpost 31, a board game. Players take on the role of characters from the film or the Thing, each aiming to defeat the other through subterfuge and sabotage.[134][135] The Thing: The Boardgame was released by Pendragon Game Studio in 2024.[136]

A pinball table based on The Thing is featured in Pinball M (2023), including R.J. MacReady and various other elements from the film.[137] Characters from, and an area based on The Thing appear in the 2024 video game Funko Fusion.[138][139]

Thematic analysis

[edit]The central theme of The Thing concerns paranoia and mistrust.[140][141][142] Fundamentally, the film is about the erosion of trust in a small community,[143] instigated by different forms of paranoia caused by the possibility of someone not being who they say they are, or that your best friend may be your enemy.[144][142] It represents the distrust that humans always have for somebody else and the fear of betrayal by those we know and, ultimately, our bodies.[142] The theme remains timely because the subject of paranoia adapts to the age. The Thing focuses on being unable to trust one's peers, but this can be interpreted as distrust of entire institutions.[145]

Developed in an era of cold-war tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, the film refers to the threat of nuclear annihilation by mutually assured destruction. Diabolique's Daniel Clarkson Fisher notes that preferring annihilation to defeat is a recurring motif, both in MacReady's destruction of the chess computer after being checkmated and his vow to destroy the Thing even at the expense of the team.[146] Clarkson Fisher and Screen Rant's Michael Edward Taylor see the team's accusatory distrust and fear of assimilation as an expression of the American Red Scare of the 1950s and 1960s, while Taylor also sees a commentary on the isolationism of the me generation in the 1970s.[141][146] Slant Magazine's John Lingsan said the men display a level of post-Vietnam War (1955–1975) "fatigued counterculturalism" – the rejection of conventional social norms, each defined by their own eccentricities.[143]

The Atlantic's Noah Berlatsky said that unlike typical horror genre films, women are excluded, allowing the Thing to be identified as a fear of not being a man, or being homosexual.[140] Vice's Patrick Marlborough considered The Thing to be a "scathing examination" of manliness, noting that identifying the Thing requires intimacy, confession, and empathy to out the creature, but "male frailty" prevents this as an option. Trapped by pride and stunted emotional growth, the men are unable to confront the truth out of fear of embarrassment or exposure.[145] Berlatsky noted that MacReady avoids emotional attachments and is the most paranoid, allowing him to be the hero. This detachment works against him in the finale, which leaves MacReady locked in a futile mistrust with Childs, each not really knowing the other.[140]

Nerdist's Kyle Anderson and Strange Horizons's Orrin Grey analyzed The Thing as an example of author H. P. Lovecraft's cosmic horror.[148][147] Anderson's analysis includes the idea of cosmic horror in large part coming "from the fear of being overtaken", connecting it to Lovecraft's xenophobia and Blair's character arc of becoming what he most fears. In contrast, Anderson compares Blair to MacReady, who represents a more traditional Hollywood film protagonist.[148] Grey describes the creature as fear of the loss of self, using Blair's character as an example. Discussing The Thing in the context of the first of three films in Carpenter's "Apocalypse Trilogy", Grey states the threat the monster poses to the world "is less disconcerting than the threat posed to the individual concept of self."[147]

The Thing never speaks or gives a motive for its actions, and ruthlessly pursues its goal.[149] Den of Geek's Mark Harrison and Ryan Lambie said that the essence of humanity is free will, which is stripped away by the Thing, possibly without the individual being aware that they have been taken over.[150][151] In a 1982 interview, when given the option to describe The Thing as "pro-science" like Who Goes There? or "anti-science" like The Thing from Another World, Carpenter chose "pro-human", stating, "It's better to be a human being than an imitation, or let ourselves be taken over by this creature who's not necessarily evil, but whose nature it is to simply imitate, like a chameleon."[70] Further allusions have been drawn between the blood-test scene and the epidemic of HIV at the time, which could be identified only by a blood test.[14][152]

Since its release, many theories have been developed to attempt to answer the film's ambiguous ending shared by MacReady and Childs.[153] Several suggest that Childs was infected, citing Dean Cundey's statement that he deliberately provided a subtle illumination to the eyes of uninfected characters, something absent from Childs. Similarly, others have noted a lack of visible breath from the character in the frigid air. While both aspects are present in MacReady, their absence in Childs has been explained as a technical issue with the filming.[154][155] During production, Carpenter considered having MacReady be infected,[156] and an alternate ending showed MacReady having been rescued and definitively tested as uninfected.[52] Russell has said that analyzing the scene for clues is "missing the point". He continued, "[Carpenter] and I worked on the ending of that movie together a long time. We were both bringing the audience right back to square one. At the end of the day, that was the position these people were in. They just didn't know anything ... They didn't know if they knew who they were ... I love that, over the years, that movie has gotten its due because people were able to get past the horrificness of the monster ... to see what the movie was about, which was paranoia."[153] However, Carpenter has teased, "Now, I do know, in the end, who the Thing is, but I cannot tell you."[157]

Legacy

[edit]Retrospective reassessment

[edit]In the years following its release, critics and fans have reevaluated The Thing as a milestone of the horror genre.[36] A prescient review by Peter Nicholls in 1992 called The Thing "a bleak, memorable film [that] may yet be seen as a classic".[158] It has been called one of the best films directed by Carpenter.[37][159][160] John Kenneth Muir called it "Carpenter's most accomplished and underrated directorial effort",[161] and critic Matt Zoller Seitz said it "is one of the greatest and most elegantly constructed B-movies ever made".[162]

Trace Thurman described it as one of the best films ever,[163] and in 2008, Empire magazine selected it as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time,[164] at number 289, calling it "a peerless masterpiece of relentless suspense, retina-wrecking visual excess and outright, nihilistic terror".[55] It is now considered to be one of the greatest horror films ever made,[161][165] and a classic of the genre.[166] Several publications have called it one of the best films of 1982, including Filmsite.org,[167] Film.com,[168] and Entertainment Weekly.[157] Muir called it "the best science fiction-horror film of 1982, an incredibly competitive year, and perhaps even the best genre motion picture of the decade".[161] Complex named it the ninth-best of the decade, calling it the "greatest genre remake of all time".[169] Numerous publications have ranked it as one of the best science fiction films, including number four by IGN (2016);[170] number 11 by Rotten Tomatoes (2024);[171] number 12 by Thrillist (2018);[172] number 17 by GamesRadar+ (2018);[173] number 31 by Paste (2018);[174] number 32 by Esquire (2015) and Popular Mechanics (2017).[175][176]

Similarly, The Thing has appeared on several lists of the top horror films, including number one by The Boston Globe;[165] number two by Bloody Disgusting (2018);[177] number four by Empire (2016);[178] and number six by Time Out (2016).[179] Empire listed its poster as the 43rd best film poster ever.[73] In 2016, the British Film Institute named it one of ten great films about aliens visiting Earth.[180] It was voted the ninth best horror film of all time in a Rolling Stone readers poll,[166] and is considered one of the best examples of body horror.[181][182][183][184] GamesRadar+ listed its ending as one of the 25 best of all time.[185] Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, which has compiled old and contemporary reviews, reports that 84% of 83 critics provided positive reviews for the film, with an average rating of 7.4/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Grimmer and more terrifying than the 1950s take, John Carpenter's The Thing is a tense sci-fi thriller rife with compelling tension and some remarkable make-up effects."[186] On Metacritic, a similar website that aggregates both past and present reviews, the film has a weighted average score of 57 out of 100 based on 13 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[187]

In a 2011 interview, Carpenter remarked that it was perhaps his favorite film from his own filmography. He lamented that it took a long time for The Thing to find a wider audience, saying, "If The Thing had been a hit, my career would have been different. I wouldn't have had to make the choices that I made. But I needed a job. I'm not saying I hate the movies I did. I loved making Christine (1983) and Starman (1984) and Big Trouble in Little China (1986), all those films. But my career would have been different."[188]

Cultural influence

[edit]The film has had a significant effect on popular culture,[163] and by 1998, The Thing was already considered a cult classic.[157][55] It is listed in the film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, which says "one of the most influential horror movies of the 1980s, much imitated but rarely bettered ... It is one of the first films to unflinchingly show the rupture and warp of flesh and bone into grotesque tableaus of surreal beauty, forever raising the bar of cinematic horror."[189] It has been referred to in a variety of media, from television (including The X-Files, Futurama, and Stranger Things) to games (Resident Evil 4, Tomb Raider III,[163] Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden,[190] and Among Us[191]), and films (The Faculty, Slither, and The Mist).[163]

Several filmmakers have spoken of their appreciation for The Thing or cited its influence on their own work, including Guillermo del Toro,[192] James DeMonaco,[193] J. J. Abrams,[194] Neill Blomkamp,[195] David Robert Mitchell,[196] Rob Hardy,[197] Steven S. DeKnight,[198] and Quentin Tarantino.[199] In 2011, The New York Times asked prominent horror filmmakers what film they had found the scariest. Two, John Sayles and Edgar Wright, cited The Thing.[200] The 2015 Tarantino film The Hateful Eight takes numerous cues from The Thing, from featuring Russell in a starring role, to replicating themes of paranoia and mistrust between characters restricted to a single location, and even duplicating certain angles and layouts used by Carpenter and Cundey.[199] Pieces of Morricone's unused score for The Thing were repurposed for The Hateful Eight.[61] Tarantino also cited The Thing as an inspiration for his 1992 film Reservoir Dogs.[12]

The film is screened annually in February to mark the beginning of winter at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station.[12][201] In January 2010, Clarkesworld Magazine published "The Things", a short story by Peter Watts told from the Thing's point of view; it is unable to understand why humans are hostile toward it and horrified to learn that they do not shapeshift. The story received a 2011 Hugo Award nomination.[12][202] In 2017, a 400-page art book was released featuring art inspired by The Thing, with contributions from 350 artists, a foreword by director Eli Roth, and an afterword by Carpenter.[203]

The 2007 Halloween Horror Nights event at Universal Studios in Orlando, Florida, featured "The Thing: Assimilation", a haunted attraction based on the film. The attraction included MacReady and Childs, both held in stasis, the Blair-Thing and the outpost kennel.[204][205]

Sequels

[edit]Dark Horse Comics published four comic book sequels starring MacReady, beginning in December 1991 with the two-part The Thing from Another World by Chuck Pfarrer, which is set 24 hours after the film.[206][207] Pfarrer was reported to have pitched his comic tale to Universal as a sequel in the early 1990s.[206] This was followed by the four-part The Thing from Another World: Climate of Fear in July 1992,[208] the four-part The Thing from Another World: Eternal Vows in December 1993,[209] and The Thing from Another World: Questionable Research.[210] In 1999, Carpenter said that no serious discussions had taken place for a sequel, but he would be interested in basing one on Pfarrer's adaptation, calling the story a worthy sequel.[23][206] A 2002 video game of the same name was released for Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 2, and Xbox to generally favorable reviews.[211][212] The game's plot follows a team of U.S. soldiers investigating the aftermath of the film's events.[213]

In 2005, the Syfy channel planned a four-hour miniseries sequel produced by Frank Darabont and written by David Leslie Johnson-McGoldrick. The story followed a Russian team who recover the corpses of MacReady and Childs, as well as remnants of the Thing. The story moves forward 23 years, where the Thing escapes in New Mexico, and follows the attempts at containment. The project never proceeded, and Universal opted to continue with a feature film sequel.[214] A prequel film, also titled The Thing, was released in October 2011 to a $31 million worldwide box office gross and mixed reviews.[215][216][217][218] The story follows the events after the Norwegian team discovers the Thing.[217] In 2020, Universal Studios and Blumhouse Productions announced the development of a remake of Carpenter's The Thing. The remake was described as incorporating elements of The Thing from Another World and The Thing, as well as the novella Who Goes There? and its expanded version Frozen Hell, which features several additional chapters.[219]

Although released years apart, and unrelated in terms of plot, characters, crew, or even production studios, Carpenter considers The Thing to be the first installment in his "Apocalypse Trilogy", a series of films based around cosmic horror, entities unknown to man, that are threats to both human life and the sense of self. The Thing was followed by Prince of Darkness in 1987, and In the Mouth of Madness in 1994. All three films are heavily influenced by Carpenter's appreciation for the works of Lovecraft.[220][147]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Leston 2022.

- ^ Shomer 2022.

- ^ a b c MacReady 2021.

- ^ a b c d Weiss 2020.

- ^ Lambie 2019.

- ^ Abrams & Zoller Seitz 2016.

- ^ Tyler 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Canby 1982.

- ^ Crowe 1995.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lyttelton 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Freer 2016.

- ^ Cohen 2011d.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kirk 2011.

- ^ Beresford 2022.

- ^ Cohen 2011i.

- ^ Cohen 2013b.

- ^ Maçek III 2012.

- ^ a b Manna 1982, p. 22.

- ^ Foster 1982b.

- ^ a b Swires 1982c, p. 26.

- ^ French 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Bauer 1999.

- ^ a b Tompkins 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hemphill 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Cohen 2013.

- ^ a b Bloody Disgusting 2014.

- ^ a b c d Abrams 2014.

- ^ a b Cinephilia Beyond 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Swires 1982, p. 16.

- ^ Swires 1982, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Billson 2009.

- ^ Swires 1982, pp. 17, 19.

- ^ a b Swires 1982, p. 19.

- ^ a b Cohen 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Abrams 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Corrigan 2017.

- ^ a b c Cohen 2011b.

- ^ Swires 1982c, p. 27.

- ^ Cohen 2011c.

- ^ Cohen 2012b.

- ^ Cohen 2012c.

- ^ a b Cohen 2012d.

- ^ a b c d e f Beresford 2017.

- ^ Cohen 2012e.

- ^ Dowd 2017.

- ^ a b c GamesRadar+ 2008.

- ^ a b The Official John Carpenter 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Swires 1982b, p. 38.

- ^ Swires 1982b, p. 39.

- ^ a b Swires 1982c, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Menzies 2017.

- ^ a b Lambie 2017a.

- ^ a b Cohen 2011e.

- ^ a b c d e Mahon 2018.

- ^ a b Cohen 2011f.

- ^ a b Whittaker 2014.

- ^ a b c d Evangelista 2017.

- ^ Fuiano & Curci 1994, p. 24.

- ^ a b Fuiano & Curci 1994, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Jagernauth 2015.

- ^ Fuiano & Curci 1994, p. 25.

- ^ Twells 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Carlomagno 1982, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Carlomagno 1982, p. 14.

- ^ Svitil 1990.

- ^ a b c Martin 2018.

- ^ Carlomagno 1982, p. 16.

- ^ Cohen 2011g.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum 1982.

- ^ Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982)

- ^ Spry 2017b.

- ^ a b Nugent & Dyer 2017.

- ^ Cohen 2011h.

- ^ a b c Cohen 2011.

- ^ Stein 1982.

- ^ a b Box Office 2018.

- ^ a b Box Office Mojo 1982.

- ^ BOMWeeks 1982.

- ^ BOM1982 1982.

- ^ a b c d e f Lambie 2018a.

- ^ Box Office Mojo 2023.

- ^ Rothkopf 2018.

- ^ Billson 1997, pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Lambie 2018b.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arnold 1982.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Spencer 1982, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e f g Denby 1982, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c d e Ansen 1982.

- ^ a b Gross 1982.

- ^ a b Kehr 1982.

- ^ a b c d e f Ebert 1982.

- ^ a b c d e Schickel 1982.

- ^ a b c d Variety 1981.

- ^ Hogan 1982, p. 3.

- ^ a b Hardy 1984, p. 378.

- ^ UPI 1983.

- ^ Saturn Awards 1982.

- ^ Lambie 2014.

- ^ Bacle 2014.

- ^ a b Nashawaty 2020.

- ^ BomBladeRunner 2018.

- ^ WeissB 2022.

- ^ Leitch & Grierson 2017.

- ^ Paul 2017.

- ^ Foster 1982b, p. 83.

- ^ Foster 1982b, p. 87.

- ^ LATMay83 1983, p. 38.

- ^ Lambie 2017b.

- ^ Deadline 2014.

- ^ Schedeen 2017.

- ^ Anderson 2008.

- ^ MediaDVDAmazon 2018.

- ^ Henderson 2004.

- ^ MediaAmazonHD06 2018.

- ^ MediaAllMov 2018.

- ^ MediaIGN08 2008a.

- ^ Liebman 2008.

- ^ a b Hunter 2016.

- ^ Spry 2017a.

- ^ Squires 2021.

- ^ Hammond 2014.

- ^ Music1991A 2018.

- ^ AICNHowarth 2011.

- ^ Lozano 2017.

- ^ Roffman 2020.

- ^ Cohen 2012f.

- ^ Foster 1982a, pp. 99–114.

- ^ Foster 1982a, pp. 189–90.

- ^ MerchBlair 2018.

- ^ MerchNorris 2018.

- ^ MerchSota1 2005.

- ^ Woods 2014.