John Yoo

John Yoo | |

|---|---|

| 유준 | |

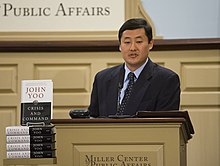

Yoo in 2012 | |

| Deputy Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel | |

| In office July 2001 – May 2003 | |

| Appointed by | Jay S. Bybee |

| President | George W. Bush |

| Member of the National Board for Education Sciences | |

| Assumed office December 2020 | |

| President | Donald Trump Joe Biden |

| General Counsel for the Senate Judiciary Committee | |

| In office July 1995 – July 1996 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Yoo Choon July 10, 1967 Seoul, South Korea |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Elsa Arnett |

| Education | Harvard University (BA) Yale University (JD) |

| Occupation | Law professor |

| Known for | "Torture Memos" (2002) |

| Awards | Federalist Society Paul M. Bator Award (2001)[1] |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 유준 |

| Hanja | 有俊 |

| Revised Romanization | Yu Jun |

| McCune–Reischauer | Yu Chun |

John Choon Yoo (Korean: 유준; born July 10, 1967)[2] is a South Korean-born American legal scholar and former government official who serves as the Emanuel S. Heller Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. Yoo became known for his legal opinions concerning executive power, warrantless wiretapping, and the Geneva Conventions while serving in the George W. Bush administration, during which he was the author of the controversial "Torture Memos" in the War on Terror.

As the deputy assistant attorney general in the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) of the Department of Justice, Yoo wrote the Torture Memos to determine the legal limits for the torture of detainees following the September 11 attacks. The legal guidance on interrogation authored by Yoo and his successors in the OLC were rescinded by President Barack Obama in 2009.[3][4][5] Some individuals and groups called for the investigation and prosecution of Yoo under various anti-torture and anti-war crimes statutes.[6][7][8][9]

A report by the Justice Department's Office of Professional Responsibility stated that Yoo's justification of waterboarding and other "enhanced interrogation methods" constituted "intentional professional misconduct" and recommended that Yoo be referred to his state bar association for possible disciplinary proceedings.[10][11][12][13] Senior Justice Department lawyer David Margolis overruled the report in 2010, saying that Yoo and Assistant Attorney General Jay Bybee—who authorized the memos—had exercised "poor judgment" but that the department lacked a clear standard to conclude misconduct.[14][12]

Early life and education

[edit]Yoo was born on July 10, 1967, in Seoul, South Korea. His parents were anti-communist, having been refugees during the Korean War. He immigrated to the United States with his family when he was a young child and grew up in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[15] He attended high school at Episcopal Academy, graduating in 1985.[16] While a student there, Yoo studied Greek and Latin.[17]

Yoo matriculated at Harvard University where he majored in American history and was a member of The Harvard Crimson.[18] He graduated in 1989 with a Bachelor of Arts, summa cum laude, with membership in Phi Beta Kappa. He then attended Yale Law School, where he was a member of the Yale Law Journal, graduating with a J.D. in 1992.[19]

Career

[edit]Early legal service

[edit]After law school, Yoo was a law clerk for Judge Laurence H. Silberman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit from 1992 to 1993 and for Justice Clarence Thomas of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1994 to 1995. He served as general counsel of the Senate Judiciary Committee from 1995 to 1996.[20]

Academic career

[edit]Yoo has been a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law since 1993, where he is the Emanuel S. Heller Professor of Law. He has written multiple books on presidential power and the war on terrorism, and many articles in scholarly journals and newspapers.[21][22] He has held the Fulbright Distinguished Chair in Law at the University of Trento and has been a visiting law professor at the Free University of Amsterdam, the University of Chicago, and Chapman University School of Law. Since 2003, Yoo has also been a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington. He wrote a monthly column, "Closing Arguments", for The Philadelphia Inquirer.[23] He has written academic books including Crisis and Command.[23]

Bush administration (2001–2003)

[edit]Yoo has been principally associated with his work from 2001 to 2003 in the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) under Attorney General John Ashcroft during the George W. Bush Administration.[17][24][6] Yoo's expansive view of presidential power led to a close relationship with Vice President Dick Cheney's office.[24] He played an important role in developing a legal justification for the Bush administration's policy in the war on terrorism, arguing that prisoner of war status under the Geneva Conventions does not apply to "enemy combatants" captured during the war in Afghanistan and held at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp.[25]

Torture memos

[edit]In what was originally known as the Bybee memo, Yoo asserted that executive authority during wartime allows waterboarding and other forms of torture, which were euphemistically referred to as "enhanced interrogation techniques"[26] were issued to the CIA. Yoo's memos narrowly defined torture and American habeas corpus obligations.[27] Yoo argued in his legal opinion that the president was not bound by the American War Crimes Act of 1996. Yoo's legal opinions were not shared by everyone within the Bush Administration. Secretary of State Colin Powell strongly opposed what he saw as an invalidation of the Geneva Conventions,[28] while U.S. Navy general counsel Alberto Mora campaigned internally against what he saw as the "catastrophically poor legal reasoning" and dangerous extremism of Yoo's opinions.[29] In December 2003, Yoo's memo on permissible interrogation techniques was repudiated as legally unsound by the OLC, then under the direction of Jack Goldsmith.[29]

In June 2004, another of Yoo's memos on interrogation techniques was leaked to the press, after which it was repudiated by Goldsmith and the OLC.[30] On March 14, 2003, Yoo wrote a legal opinion memo in response to the General Counsel of the Department of Defense, in which he concluded that torture not allowed by federal law could be used by interrogators in overseas areas.[31] Yoo cited an 1873 Supreme Court ruling, on the Modoc Indian Prisoners, where the Supreme Court had ruled that Modoc Indians were not lawful combatants, so they could be shot, on sight, to justify his assertion that individuals apprehended in Afghanistan could be tortured.[32][33]

Yoo's contribution to these memos has remained a source of controversy following his departure from the Justice Department;[34] he was called to testify before the House Judiciary Committee in 2008 in defense of his role.[35] The Justice Department's Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) began investigating Yoo's work in 2004 and in July 2009 completed a report that was sharply critical of his legal justification for waterboarding and other interrogation techniques.[36][37][38][39] The OPR report cites testimony Yoo gave to Justice Department investigators in which he claims that the "president's war-making authority was so broad that he had the constitutional power to order a village to be 'massacred.'"[12] The OPR report concluded that Yoo had "committed 'intentional professional misconduct' when he advised the CIA it could proceed with waterboarding and other aggressive interrogation techniques against Al Qaeda suspects," although the recommendation that he be referred to his state bar association for possible disciplinary proceedings was overruled by David Margolis, another senior Justice department lawyer.[12]

In 2009, President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 13491, rescinding the legal guidance on interrogation authored by Yoo and his successors in the Office of Legal Counsel.[3][4][5]

In December 2005, Doug Cassel, a law professor from the University of Notre Dame, asked Yoo, "If the President deems that he's got to torture somebody, including by crushing the testicles of the person's child, there is no law that can stop him?", to which Yoo replied, "No treaty." Cassel followed up with "Also no law by Congress—that is what you wrote in the August 2002 memo," to which Yoo replied, "I think it depends on why the President thinks he needs to do that."[40]

War crimes accusations

[edit]

Criminal proceedings against Yoo have begun in Spain: in a move that could have led to an extradition request, Judge Baltasar Garzón in March 2009 referred a case against Yoo to the chief prosecutor.[41][42] The Spanish Attorney General recommended against pursuing the case.

On November 14, 2006, invoking the principle of command responsibility, the German attorney Wolfgang Kaleck filed a complaint with the Attorney General of Germany (Generalbundesanwalt) against Yoo, along with 13 others, for his alleged complicity in torture and other crimes against humanity at Abu Ghraib in Iraq and Guantánamo Bay. Kaleck acted on behalf of 11 alleged victims of torture and other human rights abuses, as well as about 30 human rights activists and organizations. The co-plaintiffs to the war crimes prosecution included Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Martín Almada, Theo van Boven, Sister Dianna Ortiz, and Veterans for Peace.[43] Responding to the so-called "torture memoranda," Scott Horton noted

the possibility that the authors of these memoranda counseled the use of lethal and unlawful techniques, and therefore face criminal culpability themselves. That, after all, is the teaching of United States v. Altstötter, the Nuremberg case brought against German Justice Department lawyers whose memoranda crafted the basis for implementation of the infamous 'Night and Fog Decree'.[44]

Legal scholars speculated shortly thereafter that the case has little chance of successfully making it through the German court system.[45]

Jordan Paust of the University of Houston Law Center concurred with supporters of prosecution and in early 2008 criticized the US Attorney General Michael Mukasey's refusal to investigate and/or prosecute anyone who relied on these legal opinions:

[I]t is legally and morally impossible for any member of the executive branch to be acting lawfully or within the scope of his or her authority while following OLC opinions that are manifestly inconsistent with or violative of the law. General Mukasey, just following orders is no defense![46]

In 2009, the Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón Real launched an investigation of Yoo and five others (known as the Bush Six) for war crimes.[47]

On April 13, 2013, the Russian Federation banned Yoo and several others from entering the country because of alleged human rights violations. The list was a direct response to the so-called Magnitsky list revealed by the United States the day before.[48] Russia stated that Yoo was among those responsible for "the legalization of torture" and "unlimited detention".[49][50]

After the December 2014 release of the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture, Erwin Chemerinsky, then the dean of the University of California, Irvine School of Law, called for the prosecution of Yoo for his role in authoring the Torture Memos as "conspiracy to violate a federal statute".[8]

On May 12, 2012, the Kuala Lumpur War Crimes Commission found Yoo, along with former President Bush, former Vice President Cheney, and several other senior members of the Bush administration, guilty of war crimes in absentia. The trial heard "harrowing witness accounts from victims of torture who suffered at the hands of US soldiers and contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan".[51]

Warrantless wiretapping

[edit]Yoo provided a legal opinion backing the Bush Administration's warrantless wiretapping program.[24][6][52][28] Yoo authored the October 23, 2001 memo asserting that the President had sufficient power to allow the NSA to monitor the communications of US citizens on US soil without a warrant (known as the warrantless wiretap program) because the Fourth Amendment does not apply. As another memo says in a footnote, "Our office recently concluded that the Fourth Amendment had no application to domestic military operations."[53][54][55][56][57] That interpretation is used to assert that the normal mandatory requirement of a warrant, under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, could be ignored.[54][56]

In a 2006 book and a 2007 law review article, Yoo defended President Bush's terrorist surveillance program, arguing that "the TSP represents a valid exercise of the President's Commander-in-Chief authority to gather intelligence during wartime".[58] He claimed that critics of the program misunderstand the separation of powers between the President and Congress in wartime because of a failure to understand the differences between war and crime, and a difficulty in understanding the new challenges presented by a networked, dynamic enemy such as Al Qaeda. "Because the United States is at war with Al Qaeda, the President possesses the constitutional authority as Commander-in-Chief to engage in warrantless surveillance of enemy activity."[58] In a Wall Street Journal opinion piece in July 2009, Yoo wrote it was "absurd to think that a law like FISA should restrict live military operations against potential attacks on the United States."[59]

National Board for Education Sciences (2020–)

[edit]In December 2020, President Donald Trump appointed Yoo to a four-year term on the National Board for Education Sciences, which advises the Department of Education on scientific research and investments.[60][61]

Commentary

[edit]Unitary executive theory

[edit]Yoo suggested that since the primary task of the President during a time of war is protecting U.S. citizens, the President has inherent authority to subordinate independent government agencies, and plenary power to use force abroad.[62][63][16] Yoo contends that the Congressional check on Presidential war-making power comes from its power of the purse. He says that the President, and not the Congress or courts, has sole authority to interpret international treaties such as the Geneva Conventions, "because treaty interpretation is a key feature of the conduct of foreign affairs".[64] His positions on executive power are controversial because the theory can be interpreted as holding that the President's war powers afford him executive privileges which exceed the bounds which other scholars associate with the President's war powers.[64][65][66][67] His positions on the unitary executive are controversial as well because they are seen as an excuse to advance a conservative deregulatory agenda; the unitary executive theory says that every president is able to roll back any regulation passed by previous presidents, and it came to prominence in the Reagan administration as a "legal strategy that could enable the administration to gain control of the independent regulatory agencies that were seen as impeding the...agenda of deregulating business."[68]

Following his tenure as an appointee of the George W. Bush administration, Yoo criticized certain views on the separation of powers doctrine as allegedly being historically inaccurate and problematic for the global war on terrorism. For instance, he wrote, "We are used to a peacetime system in which Congress enacts the laws, the president enforces them, and the courts interpret them. In wartime, the gravity shifts to the executive branch."[69]

In 1998 Yoo criticized what he characterized as an imperial use of executive power by the Clinton administration.[70] In an opinion piece in the WSJ, he argued that the Clinton administration misused the privilege to protect the personal, rather than official, activities of the President, such as in the Monica Lewinsky affair.[70] At the time, Yoo also criticized Clinton for contemplating defiance of a judicial order. He suggested that Presidents could act in conflict with the Supreme Court, but that such measures were justified only during emergencies.[71] In 2000 Yoo strongly criticized what he viewed as the Clinton administration's use of powers of what he termed the "Imperial Presidency". He said it undermined "democratic accountability and respect for the law".[72] Yet, Yoo has defended Clinton for his decision to use force abroad without congressional authorization. He wrote in The Wall Street Journal on March 15, 1999, that Clinton's decision to attack Serbia was constitutional. He then criticized Democrats in Congress for not suing Clinton as they had sued presidents Bush and Reagan to stop the use of force abroad.[73]

Trump administration

[edit]In 2019, on Fox News, Yoo made the comment "Some might call that espionage"[74] when discussing Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, the top Ukraine expert on the National Security Council. Vindman was set to testify in front of Congress the next day about Trump requesting that the Ukrainian president start an investigation into his political rival Joe Biden. Yoo subsequently said "I really regret the choice of words" and that he had been referring to Ukrainian officials rather than Vindman.[75]

In 2020, Yoo praised Trump as a "constitutional conservative".[76] He wrote a 2020 book about Trump titled Defender in Chief: Donald Trump's Fight for Presidential Power.[77][78] During an interview on C-SPAN in August 2020, Yoo defended the use of enhanced executive privilege within the Trump administration.[79] He stated in a concurrent interview on CBS with Ted Koppel that his support for Trump may be guided by his possible reading of PEADs (Presidential Emergency Action Documents) as further supplementing his support for enhanced executive privilege during wartime and other national emergencies.[80]

After Trump lost his bid for re-election in the 2020 United States presidential election, Yoo stated in an opinion piece that the Supreme Court could decide the outcome of the election.[81] Weeks later, Yoo and J. Michael Luttig advised Mike Pence that the Vice President had no constitutional authority to interfere with the certification of Electoral College votes on January 6, 2021, as had been proposed to Pence by Trump attorney John Eastman.[82][83]

Proposed reciprocal prosecutions

[edit]At a July 2024 National Conservatism Conference meeting, former Donald Trump attorney John Eastman, who had been disbarred and was facing prosecution for his alleged role in the Pence card conspiracy to overturn the 2020 presidential election results, remarked, "We've got to start impeaching these judges for acting in such an unbelievably partisan way from the bench." Yoo responded, "People who have used this tool against people like John or President Trump have to be prosecuted by Republican or conservative DAs in exactly the same way, for exactly the same kinds of things, until they stop."[84]

Federal tort suit

[edit]On January 4, 2008, José Padilla, a U.S. citizen convicted of terrorism, and his mother sued John Yoo in the U.S. District Court, Northern District of California (Case Number 08-cv-00035-JSW), known as Padilla v. Yoo.[85] The complaint sought $1 in damages based on the alleged torture of Padilla, attributed to the authorization by Yoo's torture memoranda. Judge Jeffrey White allowed the suit to proceed, rejecting all but one of Yoo's immunity claims. Padilla's lawyer says White's ruling could have a broad effect for all detainees.[86][87][88]

Soon after his appointment in October 2003 as chief of the Office of Legal Counsel, DOJ, Jack Goldsmith withdrew Yoo's torture memoranda. The Padilla complaint, on page 20, cited Goldsmith's 2007 book The Terror Presidency in support of its case. In it Goldsmith had claimed that the legal analysis in Yoo's torture memoranda was incorrect and that there was widespread opposition to the memoranda among some lawyers in the Justice Department. Padilla's attorney used this information in the lawsuit, saying that Yoo caused Padilla's damages by authorizing his alleged torture by his memoranda.[89][90]

While the District Court ruled in favor of Padilla, the case was appealed by Yoo in June 2010. On May 2, 2012, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that Yoo had qualified immunity at the time of his memos (2001–2003), because certain issues had not then been settled legally by the U.S. Supreme Court. Based on the Supreme Court's decision in Ashcroft v. al-Kidd (2011), the Appeals Court unanimously ruled against Padilla, saying that, when he was held as a detainee, it had not been established that an enemy combatant had the "same constitutional protections" as a convicted prisoner or suspect, and that his treatment had not been legally established at the time as torture.[91]

Retired Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, chief of staff to General Colin Powell in the Persian Gulf War and while Powell was Secretary of State in the Bush Administration, has said of Yoo and other administration figures responsible for these decisions:

Haynes, Feith, Yoo, Bybee, Gonzales and—at the apex—Addington, should never travel outside the US, except perhaps to Saudi Arabia and Israel. They broke the law; they violated their professional ethical code. In the future, some government may build the case necessary to prosecute them in a foreign court, or in an international court.[92]

Office of Professional Responsibility report

[edit]The Department of Justice's Office of Professional Responsibility concluded in a 261-page report in July 2009 that Yoo committed "intentional professional misconduct" when he "knowingly failed to provide a thorough, objective, and candid interpretation of the law", and it recommended a referral to the Pennsylvania Bar for disciplinary action.[10][11] But David Margolis, a career Justice attorney,[93] countermanded the recommended referral in a January 2010 memorandum.[94] While Margolis was careful to avoid "an endorsement of the legal work," which he said was "flawed" and "contained errors more than minor", concluding that Yoo had exercised "poor judgment", he did not find "professional misconduct" sufficient to authorize OPR "to refer its findings to the state bar disciplinary authorities".[94]

Yoo contended that the OPR had shown "rank bias and sheer incompetence", intended to "smear my reputation", and that Margolis "completely rejected its recommendations".[95]

Although stopping short of referral to the bar, Margolis had also written:

[Yoo's and Bybee's] memoranda represent an unfortunate chapter in the history of the Office of Legal Counsel. While I have declined to adopt OPR's findings of misconduct, I fear that John Yoo's loyalty to his own ideology and convictions clouded his view of his obligation to his client and led him to author opinions which reflected his own extreme, although sincerely held, views of executive power while speaking for an institutional client.[94]

Margolis's decision not to refer Yoo to the bar for discipline was criticized by numerous commentators.[96][97][98][99]

Publications

[edit]Yoo's writings and areas of interest have fallen into three broad areas: American foreign relations; the Constitution's separation of powers and federalism; and international law. In foreign relations, Yoo has argued that the original understanding of the Constitution gives the President the authority to use armed force abroad without congressional authorization, subject to Congress's power of the purse; that treaties do not generally have domestic legal force without implementing legislation; and that courts are functionally ill-suited to intervene in foreign policy disputes between the President and Congress.

With the separation of powers, Yoo has argued that each branch of government has the authority to interpret the Constitution for itself.[citation needed] In international law, Yoo has written that the rules governing the use of force must be understood to allow nations to engage in armed intervention to end humanitarian disasters, rebuild failed states, and stop terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.[100][101][102][103][104]

Yoo's academic work includes his analysis of the history of judicial review in the U.S. Constitution.[105] Yoo's book, The Powers of War and Peace: The Constitution and Foreign Affairs after 9/11, was praised in an Op-Ed in The Washington Times, written by Nicholas J. Xenakis, an assistant editor at The National Interest.[106] It was quoted by Senator Joe Biden during the Senate hearings for then-U.S. Supreme Court nominee Samuel Alito, as Biden "pressed Alito to denounce John Yoo's controversial defense of presidential initiative in taking the nation to war".[107] Yoo is known as an opponent of the Chemical Weapons Convention.[108]

During 2012 and 2014, Yoo published two books with Oxford University Press. Taming Globalization was co-authored with Julian Ku in 2012, and Point of Attack was published under his single authorship in 2014. His 2017 book Striking Power: How Cyber, Robots, and Space Weapons Change the Rules for War is co-authored with by Jeremy Rabkin.

Yoo's latest book, Defender in Chief: Donald Trump's Fight for Presidential Power, was published in July 2020.[109]

Bibliography

[edit]- Yoo, John (2005). The Powers of War and Peace: The Constitution and Foreign Affairs after 9/11. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-96033-3.

- Yoo, John (2006). War by Other Means: An Insider's Account of the War on Terror. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-1-55584-763-0.

- Yoo, John (2010). Crisis and Command: A History of Executive Power from George Washington to George W. Bush. Kaplan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60714-555-4.

- Ku, Julian; Yoo, John (2012). Taming Globalization: International Law, the U.S. Constitution, and the New World Order (co-author Julian Ku). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983742-7. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

- Yoo, John (2014). Point of Attack: Preventive War, International Law, and Global Welfare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-934776-6. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

- Rabkin, Jeremy; Yoo, John (2017). Striking Power: How Cyber, Robots, and Space Weapons Change the Rules for War. Encounter Books. ISBN 978-1-59403-888-4.

- Yoo, John (July 28, 2020). Defender in Chief: Donald Trump's Fight for Presidential Power. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-250-26961-4. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

He has also contributed chapters to other books, including:

- Berkowitz, Peter (2005). "Enemy Combatants and the Problem of Judicial Competence" (PDF). Terrorism, the Laws of War, and the Constitution: Debating the Enemy Combatant Cases. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-4622-7.

In popular culture

[edit]- In Vice, a 2018 biographical comedy-drama film about Dick Cheney, Yoo is portrayed by Paul Yoo.[110]

- In The Report, a 2019 film about the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture, Yoo is portrayed by Pun Bandhu.[111]

Personal life

[edit]Yoo is married to Elsa Arnett, the daughter of journalist Peter Arnett.[112]

See also

[edit]- Extraordinary rendition by the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 10)

- U.S. Army and CIA interrogation manuals

References

[edit]- ^ "Past Bator Award Recipients". fed-soc.org. Archived from the original on May 19, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Contemporary Authors Online, Thomson Gale, 2008.

- ^ a b White House Office of the Press Secretary (January 22, 2009). "Executive order: Interrogation". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Warrock, Joby; DeYoung, Karen (January 23, 2009). "Obama Reverses Bush Policies On Detention and Interrogation". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Arsenault, Elizabeth Grimm (May 8, 2018). "Analysis | With (or without) Gina Haspel at CIA, could Trump revive the torture program?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c Richardson, John (May 13, 2008). "Is John Yoo a Monster?". Esquire. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times Editorial Board (December 22, 2014). "Opinion | Prosecute Torturers and Their Bosses". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Wiener, Jon (December 12, 2014). "Prosecute John Yoo, Says Law School Dean Erwin Chemerinsky". The Nation. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (April 2, 2008). "John Yoo's War Crimes". Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ a b Justice Department OPR Report. U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary (Report). July 29, 2009. Archived from the original on May 8, 2010.

- ^ a b Department of Justice Office of Professional Responsibility (July 29, 2009). Investigation into the Office of Legal Counsel's Memoranda Concerning Issues Relating to the Central Intelligence Agency's Use of "Enhanced Interrogation Techniques" on Suspected Terrorists (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Isikoff, Michael (February 19, 2010). "Report: Bush Lawyer Said President Could Order Civilians to Be 'Massacred'". Newsweek. Archived from the original on September 7, 2014.

- ^ Hunt, Kasie (February 19, 2010). "Justice: No misconduct in Bush interrogation memos". POLITICO. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ Hunt, Kasie (February 19, 2010). "Justice: No misconduct in Bush interrogation memos". POLITICO. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, John H. (May 12, 2008). "John Yoo: In His Own Words". Esquire. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Slevin, Peter (December 26, 2005). "Scholar Stands by Post-9/11 Writings On Torture, Domestic Eavesdropping". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010.

- ^ a b Barrett, Paul M. (September 12, 2005). "A Young Lawyer Helps Chart Shift in Foreign Policy: Prof. Yoo Sees Broad Powers For Presidents at War". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- ^ "A Parting Shot". The Harvard Crimson. February 3, 1988. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ "PA Attorney Information John Choon Yoo". The Disciplinary Board of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ "Berkeley Law – Faculty Profiles". UC Berkeley School of Law. n.d. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "Bibliography". American Enterprise Institute. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009.

- ^ "Bibliography". Social Science Research Network. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Yoo, John (December 20, 2009). "Closing Arguments: Platitudes won't guarantee world peace". American Enterprise Institute. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c Golden, Tim (December 23, 2005). "A Junior Aide had a big role in Terror Policy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ "Frontline Interview with John Yoo". Frontline. PBS. July 19, 2005. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Stout, David (January 15, 2009). "Holder tells Senators Waterboarding is Torture". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ "Bush Admits To Knowledge of Torture Authorization by Top Advisers". American Civil Liberties Union. Archived from the original on October 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Isikoff, Michael (May 17, 2004). "Memos Reveal War Crimes Warnings". Newsweek. Archived from the original on September 14, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Mayer, Jane (February 27, 2006). "The Memo: How an Internal Effort to Ban the Abuse and Torture of Detainees was Thwarted". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (September 9, 2007). "Conscience of a Conservative". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ Isikoff, Michael (April 5, 2008). "A Top Pentagon Lawyer Faces a Senate Grilling On Torture". Newsweek. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^

Nick Estes (January 11, 2017). "Indian Killers: Crime, Punishment, and Empire". The Red Nation. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

Consider former Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo's 2003 'torture memos' in support of torture in the War on Terror. As Chickasaw scholar Jodi Byrd notes, Yoo cited the 1873 Modoc Indian Prisoners Supreme Court opinion that justified the murder of Indians by U.S. soldiers. 'All the laws and customs of civilized warfare,' the Court opined, 'may not be applicable to an armed conflict to Indian tribes on our Western frontier.' 'Indians' were legally killable because they possessed no rights as 'enemy combatants,' as it is with those now labeled "terrorist."

- ^

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). "An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States". Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000410. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

Drawing a legal analogy between the Modoc prisoners and the Guantánamo detainees, Assistant US Attorney General Yoo employed the legal category of homo sacer—in Roman law, a person banned from society, excluded from its legal protections but still subject to the sovereign's power. Anyone may kill a homo sacer without it being considered murder. To buttress his claim that the detainees could be denied prisoner of war status, Yoo quoted from the 1873 Modoc Indian Prisoners opinion...

- ^ Lithwick, Dahlia (March 19, 2010). "It's Not Me. It's Yoo". Slate. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Eggen, Dan (June 27, 2008). "Bush Policy authors defend their actions". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Shane, Scott (February 16, 2009). "Justice Dept to Critique Interrogation Methods Backed by Bush Team". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 31, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Shane, Scott (February 23, 2009). "Waterboarding Focus of Inquiry by Justice Dept". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Johnston, David; Scott Shane (May 6, 2009). "Interrogation Memos: Inquiry Suggests no Charges". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "OPR Final Report" (PDF). Committee on the Judiciary. July 29, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ Hentoff, Nat (July 3, 2007). "Architect of Torture". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Borger, Julian (March 29, 2009). "Spanish judge to hear torture case against six Bush officials". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Rucinski, Tracy (March 28, 2009). "Spain may decide Guantánamo probe this week". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 26, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Zagorin, Adam (November 10, 2006). "Charges Sought Against Rumsfeld Over Prison Abuse". Time. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Abraham, David (May 2007). "The Bush Regime from Elections to Detentions: A Moral Economy of Carl Schmitt and Human Rights". University of Miami Legal Studies. University of Miami Law School. SSRN 942865. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020 – via SSRN.

- ^ Purvis, Andrew (November 16, 2006). "Report on lawsuit against Yoo, et al". Time. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Paust, Jordan (February 18, 2008). "Just Following Orders? DOJ Opinions and War Crimes Liability". Jurist. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (March 28, 2009). "Spanish Court Weighs Inquiry on Torture for 6 Bush-Era Officials". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Russia hits back at US with its own blacklist". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ Barry, Ellen (April 13, 2013). "Russia Bars 18 Americans After Sanctions by U.S." The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ Englund, Will (April 14, 2013). "Russia retaliates against U.S., bans American officials". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ Ridley, Yvonne (May 12, 2012). "Bush Convicted of War Crimes in Absentia". Foreign Policy Journal. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ Shapiro, Walter (February 23, 2006). "Parsing Pain". Salon.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ Opsahl, Kurt (2009). "Bush Administration Claimed Fourth Amendment Did Not Apply to NSA Spying". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved March 2, 2009.

- ^ a b Weiss, Debra Cassens (April 4, 2008). "DOJ Endorsed Terrorism Exception to 4th Amendment in Another Disavowed Memo". ABA Journal. American Bar Association. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008.

- ^ "Bush Administration Memo Says Fourth Amendment Does Not Apply To Military Operations Within U.S." ACLU. April 2, 2008. Archived from the original on October 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Hess, Pamela; Jordan, Lara Jakes (April 3, 2008). "Memo linked to warrantless surveillance". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008.

- ^ Opsahl, Kurt (April 2, 2008). "Administration Asserts No Fourth Amendment for Domestic Military Operations". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Yoo, John C. (March 27, 2007). "The Terrorist Surveillance Program and the Constitution". Geo. Mason L. Rev. 14: 565. SSRN 975333. Archived from the original on January 10, 2020.

- ^ Yoo, John (July 16, 2009). "Why We Endorsed Warrantless Wiretaps". The Wall Street Journal. p. A13. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017.

- ^ Sparks, Sarah D. (December 14, 2020). "Researchers Balk at Trump's Last-Minute Picks for Ed. Science Board". Education Week. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Mervis, Jeffrey (December 11, 2020). "Researchers decry Trump picks for education sciences advisory board". Science | AAAS. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Blumenthal, Sidney (January 12, 2006). "George Bush's rough justice – The career of the latest supreme court nominee has been marked by his hatred of liberalism". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020.

- ^ Garbus, Martin (January 20, 2006). "How Close Are We to the End of Democracy?". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008.

- ^ a b "An interview with John Yoo: author of The Powers of War and Peace: The Constitution and Foreign Affairs after 9/11". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on January 16, 2006.

- ^ Maxwell, Mary (December 9, 2005). "A Wunnerful, Wunnerful Constitution, John C. Yoo Notwithstanding". After Downing Street. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008.

- ^ "The Unitary Executive in the Modern Era, 1945–2001" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 8, 2006., Vanderbilt University

- ^ Blumenthal, Sidney (January 12, 2006). "Meek, mild and menacing". Salon.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008.

- ^ Ellis, Richard (2017). "Resolved: The Unitary Executive is a Myth". In Nelson, Michael (ed.). Debating the Presidency: Conflicting Perspectives on the American Executive. CQ Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-1506344485. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

- ^ Egelko, Bob (September 10, 2006). "9/11: Five years later: Bush continues to wield power". San Francisco Chronicle. p. E-2. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Yoo, John C. (March 2, 1998). "A Privileged Executive?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Yoo, John (July 20, 1998). "Subpoenaing the President". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017.

- ^ Yoo, John (2000). "The Imperial President Abroad". In Pilon, Roger (ed.). The Rule of Law in the Wake of Clinton. Cato Institute. p. 159. ISBN 9781930865037. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

- ^ Yoo, John (March 15, 1999). "Opinion: War Powers: Where Have All the Liberals Gone?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017.

- ^ Feldman, Josh (October 29, 2019). "Fox News Panel Heavily Speculates About Alexander Vindman". Mediaite. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Mazza, Ed (October 31, 2019). "Fox News Guest 'Regrets' Explosive Espionage Claim, Admits Trump Quid Pro Quo". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020.

- ^ Saunders, Debra J. (August 2, 2020). "Trump meets with John Yoo at White House". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Borger, Julian (July 20, 2020). "Trump consults Bush torture lawyer on how to skirt law and rule by decree". the Guardian. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "Defender in Chief". US Macmillan. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "Executive Power and the Constitution". C-SPAN. August 3, 2020. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Deirdre (August 16, 2020). Givnish, Ed (ed.). "Rewriting the limits of presidential powers". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 2, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Yoo, John (November 6, 2020). "John Yoo: Trump-Biden presidential race could be decided by Pennsylvania case before Supreme Court". Fox News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Peter; Haberman, Maggie; Karni, Annie (January 13, 2021). "Pence Reached His Limit With Trump. It Wasn't Pretty". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ Naham, Matt (January 13, 2021). "These Are the Lawyers Who Told Mike Pence That, Despite Trump's Pressure Campaign, VP Had No Power to Overturn Election Results". Law and Crime.

- ^ Weigel, David (July 9, 2024). "Trump's 'national conservative' allies plot a revenge administration". Semafor.

- ^ Yoo, John (January 19, 2008). "Opinion: Terrorist Tort Travesty". The Wall Street Journal. p. A13. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

Last week, I (a former Bush administration official) was sued by José Padilla—a 37-year-old al Qaeda operative convicted last summer of setting up a terrorist cell in Miami. Padilla wants a declaration that his detention by the U.S. government was unconstitutional, $1 in damages, and all of the fees charged by his own attorneys.

- ^ American Civil Liberties Union (April 22, 2009). "Index of Bush-Era OLC Memoranda Relating to Interrogation, Detention, Rendition and/or Surveillance" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ White, Jeffrey S. (June 12, 2009). "Order Denying in Part and Granting in Part Defendant's Motion to Dismiss (Document #68 in José Padilla and Estela Lebron v. John Yoo, case No. C 08-00035 JSW)". Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Schwartz, John (June 13, 2009). "Judge Allows Civil Lawsuit Over Claims of Torture". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- ^ Anderson, Curt (January 4, 2008). "Padilla sues ex-Bush Official over memos". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ Cassel, Elaine (January 4, 2008). "Jose Padilla's suit against John Yoo: an interesting idea, but will it get far?". FindLaw. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ "Padilla v. Yoo | 678 F.3d 748 (2012) | 20120502152". Leagle. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (April 19, 2008). "Top Bush aides pushed for Guantánamo torture". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Smith, R. Jeffrey (February 28, 2010). "Lessons from the Justice Department's report on the interrogation memos". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c Margolis, David (January 5, 2010). "Memorandum of Decision Regarding the Objections to the Finding of Professional Misconduct in the Office of Professional Responsibility's Report of Investigation into the Office of Legal Counsel's Memoranda Concerning Issue Relating to the Central Intelligence Agency's Use of 'Enhanced Interrogation Techniques' on Suspected Terrorists" (PDF). U.S. House of Representatives House Committee on the Judiciary. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 5, 2010.

- ^ Yoo, John (February 24, 2010). "Opinion: My Gift to the Obama Presidency". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017.

- ^ Luban, David (February 22, 2010). "David Margolis Is Wrong". Slate. Archived from the original on December 1, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ Lithwick, Dahlia (February 22, 2010). "Torture Bored: How we've erased the legal lines around torture and replaced them with nothing". Slate. Archived from the original on December 1, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ Cole, David D. (2010). "The Sacrificial Yoo: Accounting for Torture in the OPR Report". Journal of National Security Law & Policy. 4: 477. Archived from the original on December 1, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ Horton, Scott (February 24, 2010). "The Margolis Memo". Harper's Magazine. Archived from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ Nzelibe, Jide; Yoo, John (March 30, 2006). "Rational War and Constitutional Design". Yale Law Journal. 115 (9): 2512. doi:10.2307/20455704. JSTOR 20455704. S2CID 153917284 – via Social Science Research Network.

- ^ Yoo, John (2004). "War, Responsibility, and the Age of Terrorism". Stanford Law Review. 57 (3): 793–823. JSTOR 40040189 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Yoo, John C. (1999). "Globalism and the Constitution: Treaties, Non-Self-Execution, and the Original Understanding". Columbia Law Review. 99 (8): 1955–2094. doi:10.2307/1123607. JSTOR 1123607. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009.

- ^ Yoo, John C. (June 1, 2004). "Using Force". University of Chicago Law Review. 71: 729. SSRN 530022. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020.

- ^ Yoo, John C.; Ku, Julian (January 23, 2005). "Beyond Formalism in Foreign Affairs: A Functional Approach to the Alien Tort Statute". Supreme Court Review. 2004. SSRN 652141. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020.

- ^ Prakash, Saikrishna; Yoo, John (2003). "The Origins of Judicial Review". University of Chicago Law Review. 70 (3): 887–982. doi:10.2307/1600662. JSTOR 1600662 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Xenakis, Nicholas J. (October 25, 2005). "Congress goes wobbly". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Bessette, Joseph M. (Spring 2006). "The War Over the War Powers". Claremont Review of Books. Archived from the original on April 10, 2007.

- ^ "The U.S. Debate Over the CWC: Supporters and Opponents". The Henry L. Stimson Center. 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ^ Yoo, John (2020). Defender in Chief: Donald Trump's Fight for Presidential Power. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-250-26961-4. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

- ^ "Vice (2018) – Full Cast & Crew". IMDb. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "The Report (2019) – Full Cast & Crew". IMDb. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Carol J. (March 29, 2010). "In Berkeley, Yoo feels at home as a stranger in a strange land". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010. Arnett is the daughter of journalist Peter Arnett.

External links

[edit]- Appearances on C-SPAN

- John Yoo on Charlie Rose

- John Yoo at IMDb

- John Yoo collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- 1967 births

- American Enterprise Institute

- American foreign policy writers

- American jurists of Korean descent

- American legal scholars

- American legal writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- American political writers

- American politicians of Korean descent

- Asian conservatism in the United States

- Asian-American people in Pennsylvania politics

- Episcopal Academy alumni

- George W. Bush administration personnel

- Harvard College alumni

- John M. Olin Foundation

- Law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Living people

- Pennsylvania lawyers

- Pennsylvania Republicans

- Lawyers from Seoul

- South Korean emigrants to the United States

- Torture in the United States

- UC Berkeley School of Law faculty

- War on terror

- Yale Law School alumni