Joe Martin (orangutan)

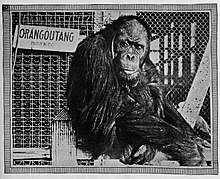

Joe Martin at Universal City Zoo, 1919 | |

| Other name(s) | Chimpanzee Charlie, Giant Gorilla Man |

|---|---|

| Species | Pongo (genus), species unidentified |

| Sex | Male |

| Born | Indonesian archipelago |

| Died | Unknown |

| Occupation | Animal actor, circus-zoo animal |

| Years active | 1914–1931 |

| Owners | Robison brothers, Sam Behrendt, Universal Pictures, Barnes Circus |

| Weight | 185 lb (84 kg) |

| Height | 65 in (170 cm) |

Joe Martin (born between 1911 and 1913 – died after 1931) was a captive orangutan who appeared in at least 50 American films of the silent era, including approximately 20 comedy shorts, several serials, two Tarzan movies, Rex Ingram's melodrama Black Orchid and its remake Trifling Women, the Max Linder feature comedy Seven Years Bad Luck, and the Irving Thalberg-produced Merry-Go-Round.

Joe Martin was human-acculturated and was characterized as human-like during his life. Upon entering adolescence, Joe Martin began to physically attack humans and other animals, including studio staff, director Al Santell, his trainers, and actors including Dorothy Phillips and Edward Connelly. At least three of these cases were apparent defenses of a woman, child, or animal. He staged major zoo escapes at least twice, once releasing the wolves and the elephant on the way out, and, separately, while evading recapture, relieving a police officer of his gun.

In 1924, Universal Pictures deemed Joe Martin too dangerous to work in film and sold him to the Al G. Barnes Circus, where he remained until approximately 1931. Although the circumstances of his death are unknown, Joe Martin had a long lifespan for a captive orangutan of his era.

Background

[edit]

Prior to 1924, there were no legal prohibitions against killing, capturing, or selling orangutans.[1][2][3] In the 19th and early 20th century, selling orangutans was profitable for an elaborate network of hunters, middlemen, and dealers.[2] Orangutan hunting and trapping has been illegal in Indonesia since 1931,[3] but trading remained widespread until the mid-20th century[1] and provincial hunting and trading persists in the 21st century.[4]

According to zoologists, captive orangutan survival rates were dismal[2] and lifespans short.[1][5] Death rates were high in part because members of the Pongo genus are highly susceptible to human-transmitted respiratory infections.[6][7][8] An estimated 60 percent of trafficked orangutans died in passage, and the majority of the survivors died within their first year in overseas captivity.[2] In the first decades of the 20th century, it was uncommon for orangutans to survive more than 18 months in captivity.[2][9] Prior to the 1920s, the longest an orangutan had ever survived in captivity was six years; the mean lifespan for all captive orangutans was three-and-a-half years.[10]

In the United States, exotic animal dealers provided a steady supply of captured wild animals in response to a robust demand from wealthy private collectors, traveling circuses, roadside zoos, vaudeville shows, and the burgeoning international film industry.[11][12] As one historical review of stunt performers and lion tamers described it, "Filmmakers were drawn to wild animals as a practical means of creating cinematic spectacle."[13]

In the early years of the 20th century, and as the film industry moved west to Los Angeles, the city simultaneously became "the national center for wild animals and their trainers".[13] Joe Martin likely spent most of his life in two Los Angeles settlements—Universal City and Barnes City—that were established specifically to sell spectacle.[14][15]

Biography

[edit]Transoceanic shipment and first owners

[edit]Various contemporaneous news stories suggested he was born between 1912 and 1914, and several, but not all, say he came from Borneo, homeland of the Bornean orangutan[16] (Pongo pygmaeus).[9][17][18][19] Research into the history of primate trafficking has found that "while the orangutan was most closely associated with the island of Borneo, by the early 1900s a majority of orangutans on the global market were captured in, and exported from, northern Sumatra."[2] Sumatra is the homeland of the surviving populations of Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii)[20] and Tapanuli orangutans (Pongo tapanuliensis).[21]

Joe Martin's primary trainer told several reporters that Joe Martin could have been as young as five or six months old when he arrived.[22] As with all primates, the mother-child dyad is foundational to infant survival, and young orangutans are heavily dependent on maternal care until at least age eight, "thus obtaining infants requires mothers to be killed in nearly all instances".[23]

According to Camera! and the San Antonio Express, Joe Martin first arrived to the United States in 1911 in San Francisco via Singapore, in a "consignment of animals shipped by Frank Buck"[24][a] to the animal dealer Robison of San Francisco. Robison then sold Joe Martin for US$250 (equivalent to $8,175 in 2023) to a Los Angeles insurance company owner named Sam Behrendt.[24][b] Behrendt put Joe Martin in an exhibit at Venice Pier called The Missing Link, where he was under the care of animal trainer "Pop" Saunders.[24] Saunders had "trained hundreds of animals for the circus arena and for the movies."[28]

After a fire at the pier,[c] Saunders relocated with Joe Martin to Universal's "Old Ranch".[24][d] At that time, Universal was leasing several animals from the Sells Floto Circus for a film, and someone suggested including an orangutan.[28] Charles B. Murphy is said to have prepared Joe Martin for his first picture, a one-reel comedy directed by Allen Turner, after which Universal bought Joe Martin from Behrendt for an undisclosed sum.[24] Another source says that Joe Martin's first American trainer was Red Gallagher.[17][e] A third source, the posthumously published memoir of circus operator Alpheus George Barnes Stonehouse, states, "Joe Martin, the famous orang-utan movie star, was bought by my brother Jerry M. Barnes for the Universal Motion Picture Company. My brother started training him for the movies and his training was finished by Mr. Murphy, who worked for the Universal."[30][31]

1915–1917: Breakout film and early work

[edit]

With few exceptions, Joe Martin's short comedies are all believed to be lost films. As such, most[f] of Joe Martin's film work, like many silent films, is known to film historians only through marketing materials, production stills, and media mentions.[32][33][34] A portion of the Universal lot in the San Fernando Valley housed a wide array of performing animals; many silent-era animal scenes were shot in a central area of the Universal City Zoo called the arena.[13] Joe Martin's breakout role was a two-reel short called Joe Martin Turns 'Em Loose "produced at the famous Universal City Zoo"[35] and released in 1915. The film seems to have been a comedy about opening the animal cages at a zoo and sending a stampede of beasts after bystanding humans.[36][37] Prior to the success of this film, Joe Martin was known as "Chimpanzee Charlie".[38][39]

Around 1915, an animal trainer named Curley Stecker began taking care of Joe Martin.[40] According to Frank Buck, Joe Martin was cross-fostered by the Steckers: "He was taken into Curley's house to be raised...[and] grew up with the Stecker son".[41] Curley is sometimes credited with "discovering" Joe Martin;[33] they worked as a team for the next eight years.[42] Stecker's family would sometimes appear alongside Joe Martin in films.[43][44][45][46] The Stecker family rented a house across the road[22][47][48] from the studio zoo, the zoo having been created in part as a "point of interest" at Universal City.[49] The keepers were responsible for introducing the animals to visiting dignitaries;[50][51] one such visit was made by Bishop Hanna of San Francisco in 1915.[52] Later, one of Joe Martin's directors wrote of the visit: "A famous old prelate came out to Universal City to see Joe. Joe listened while the old gentleman commented on the wonders of nature. 'You wouldn't catch a monkey taking a drink of vile liquor,' he observed. Joe reached in the hip pocket of his little pantaloons and came out with a pint of liquor, which he offered to the bishop with fine courtesy."[53]

In the first three years of his career, Joe Martin appeared in at least 20 films, including Rex Ingram's vampy feature melodrama Black Orchids. (Five years later, Joe Martin later played the same part in the retitled remake Trifling Women, which turned out to be one of his last on-screen credits.)[33] According Universal's in-house magazine Moving Picture Weekly, Joe Martin may have costarred with Wallace Beery in one or more shorts called The Janitor, directed by Beery and released in 1916.[54] The article about Beery's films noted that Joe Martin was "absolutely devoted" to zoo superintendent Rex De Rosselli and never let De Rosselli pass by without a hug; Joe Martin was not as affectionate with Beery.[54] A news item about a Joe Martin one-reel directed by De Rosselli noted, "The simian seems to understand what his director tells him, and he is doing some wonderful work."[55]

A 1916 magazine feature on "Making Pictures in California" reported of the recently opened Universal zoo: "Here we find Joe, the chimpanzee, who sleeps in a regular brass bed, uses a toothpick after meals, etc."[56] Joe Martin was taught to wear clothes and given a weekly shave, and seemed to enjoy the latter, although if the razor was dull, he was known to throw things at the barber.[28] On the occasions when he was allowed to roam the lot and was thirsty, he knew to put his thumb over the faucet spigot to direct the stream of water into his mouth.[28] Joe Martin reportedly attempted to escape the Universal lot in the summer of 1917, but his child costar Lena Baskette lured him back to his enclosure.[57] Meanwhile, human-interest blurbs about Joe Martin were being placed in regional newspapers: "Joe recently received a letter...reading as follows: 'Dear Joe Martin: I wish you would send me your picture. My papa says you are only a monkey, but I think you are an actor."[58]

1918: Influenza epidemic, and night-watchman incident

[edit]

In November 1918, as the Spanish flu pandemic reached the west coast and Universal and other studios shut down for a month to prevent further spread,[59] Joe Martin was infected with the virus but was "narrowly saved" from death by double pneumonia through the combined efforts of Dr. Richard Goodwin[g] and Curley Stecker.[61] A film magazine said that while he was ill, Joe Martin "wasted away to the form of a skeleton."[62] Three years after the fact, a Boston paper reported that Joe Martin had "hovered between life and death" for nearly three weeks, but "all day, and frequently through the long nights of his illness, Stecker remained within the cage with him."[63] Afterward, Billboard reported that Joe Martin wore a flu mask[64] in the hopes of reducing transmission to the other animals in the menagerie.[61][62]

Joe Martin worked with child actors frequently, including in the 1918 film Man and Beast,[65] where his child costar was likely Curley Stecker's two-year-old son.[44]

In late 1918, Universal security guard Thomas G. Cockings made the first public allegation that Joe Martin had assaulted a human in a $10,000 (equivalent to $202,566 in 2023) lawsuit. Cockings claimed that Joe Martin had bitten him 40 times on the legs. The studio claimed at the Superior Court hearing that Joe Martin was "lovable," sharing photos of him walking with and embracing women, holding a baby, and wearing a flu mask, while one witness for the company testified that Joe Martin had hugged and kissed him at their first meeting.[66] The outcome of the case was not publicized, but in 1920 actor-director Al Santell told Photoplay, "There was a night watchman at the menagerie for a while who always carried a bottle with him on his rounds and now and then he'd give Joe a drink. But one night when he was three sheets to the wind he put red pepper in the whisky and oh boy! Joe nearly went crazy trying to get at the man...But he never hurts a woman or a child. When we use babies in the animal comedies they are absolutely safe with him."[67]

1919: Escapes and Al Santell incident

[edit]

Business-wise, in 1919, when other film companies wanted to use him, Joe Martin's rental rate was said to be $100 a day. Universal thought he was worth $7,000 to $10,000.[68] On the personal-life front, he had the frequent company of a small monkey called Skipper, and was said to "get along alright" with children, kittens, and lion cubs.[17][68][69] An advertisement in a Canadian newspaper for Universal's two-reeler Jazz Monkey included a humorous essay about Joe Martin's diet which stated that Joe Martin consumed a vegetarian diet of carrots, turnips, onions, corn on the ears, alligator pears, "root beer, ice-cream soda, coco-cola, or malted milk, to any extent a friend is able to buy," and "tobacco in moderation, preferring the smokeless variety."[70] A later report said that Joe Martin's diet usually consisted of vegetables and a mixture of malted milk and warm water, sometimes supplemented with eggs "to give it more body and flavor." Sunday was a day of fasting for the zoo, followed by a richer meal than usual on Monday morning.[71]

In June, Universal bought a full-page ad in Wid's Filmdom for an open letter to the industry. The letter, signed by Universal's founding mogul, Carl Laemmle, called Joe Martin "the only guaranteed star on the screen" and stated:[72]

We have made a real actor of him. True, he is temperamental, as nearly all stars are; but we have never yet seen any star who was more willing, more daring, more clever or more brainy…He has shown a spirit of true manliness. For this and many other reasons I feel that I owe him this public appreciation.[72]

A couple of months later, Universal published an anecdote about the filming of Jazz Monkey in the "Joe Martin Soliloquizes" ad series, which was written from Joe Martin's point of view. In a scene where Joe Martin was due to confront the lion endangering the heroine, the ad read, "I was afraid the gun wouldn't go off (property men are merely human) so I gave it an affectionate kiss just before I pulled the trigger and said in an offhand sort of way, 'Sweet baby don't fail me now!'...Well, sir, darn if the title writer didn't swipe the whole line, word for word, exactly as I said it...I wasn't even trying to be funny, yet they laughed."[73]

In June 1919, Joe Martin attended a screening of his own film, Monkey Stuff, put on by the Los Angeles Evening Herald as an employment perk for its newsboys.[74] Martin wore a Palm Beach suit, carried a cane, and "clapped his hands frequently and laughed monkey laughs whenever anything struck him as being particularly good."[74] Another article reported that Joe Martin looked back and forth between his hands and the screen several times before "he apparently came to the conclusion that it was himself he was looking at."[75] Around the same time, an Ohio columnist reported that Joe Martin finger-combed his hair in the mornings, and turned the mirror to face the wall on bad hair days.[76] The writer also made impressive primate cognition claims about Joe Martin: "The remarkable animal understands any spoken command, even listens in on private conversations and does stunts that were suggested for him but rejected by the trainer...His mental processes function without command from the trainer, an unusual trait. Upon leaving his cage he will carefully close the doors, slipping the hasp over its staple."[76] A 1924 report claimed "he would pull a key ring out of his pocket, select the right key, and unlock his cage."[77]

In July 1919, Joe Martin escaped from the zoo and went on a multi-day rampage in which time he wrecked an assistant trainer's quarters, released approximately 15 wolves,[h] freed Charlie the Elephant, and created general havoc.[79] Joe Martin then scaled the Universal barn and refused to leave the roof for hours. His trainer placed food in his cage, but when Joe Martin finally came down, he ripped the cage door off its hinges before entering so he could not be trapped while collecting his meal. After some time, Joe Martin was found sleeping in the warm sand of a dry creek bed .5 mi (800 m) from the studio. Curley Stecker was able to lasso him and return him to custody.[28] Meanwhile, an Omaha, Nebraska newspaper entertainment columnist reported that Joe Martin escaped the arena, got to a main road and encountered an "honest-to-goodness evangelist preaching to his flock from a portable tabernacle on wheels." (This may have been during the escape described above.) Apparently Joe Martin had filmed a scene in a William S. Campbell comedy where he "broke up a church meeting" and so repeated the scene in real life. "After the worshippers had scattered and the minister was safe on top of a telephone pole," Joe Martin carried on with his day.[80]

While filming a William S. Campbell comedy, Joe Martin was present during a scene in which a "hard-fried miner" spanked a child. While the scene's choreography prevented the child from being injured, it reportedly appeared realistic to Joe Martin, who confronted the actor: "Stepping down from his chair, Joe rushed the offending player. He grappled him around the ankles and tripped him up with a flying tackle that would have done wonders for a collegiate pigskinner. Having upset his victim, Joe stood over him, grinning evilly with long, barbed teeth and gathered the little kid to his hairy breast with his free arm."[81]

The Los Angeles Times published advertorial photos of Joe Martin behind the wheel of a Kissel automobile and claimed that he had learned to drive.[75] The content was created by Western Motor Company, Kissel distributors, and was designed to show that driving was easy.[75] The paper also claimed that Joe Martin had recently ridden in an airplane piloted by a barnstormer contracted to Universal, Lt. Ormer Locklear.[75]

In November 1919, Joe Martin attacked his director. In a Camera! column, Harry Burns (who would go on to direct Joe Martin) reported that "Al Santell is nursing a badly lacerated hand and foot after having a none-too-friendly set-to with Joe Martin."[82] As reported in 1920, Al Santell "remonstrated" with Joe about slamming a door too hard and breaking the set, so Joe Martin caught "him by the ankle...took him over and rolled him down the stairs."[40] According to one newspaper report, in his fall down two flights of stairs, Santell suffered "a badly wrenched arm, a cut on the cheek, a sprained leg and numerous bruises. Joe Martin assured the director that it was merely a disciplinary measure and that there was no malice behind the act."[83]

1920: Tarzan incident

[edit]

Joe Martin may have attacked Al Santell a second time, on the set of A Wild Night (1920). In a 1972 interview surfaced by film historian Steve Massa, Santell said, "When a chimpanzee [sic] bites you, he doesn't just give you one quick bite—he clamps his teeth in, gets set, and then puts on the pressure. And I could feel each tooth mauling into my leg." It took the combined strength of Curley and Carl Stecker[i] to detach Joe Martin from his director.[85] In March, Popular Science published a photo feature on the animals of the Universal City Zoo, their trainers, and their film performances. Joe Martin and Curley Stecker made multiple appearances in the magazine spread; Charlie the Elephant and Ethel the Lioness were also photographed.[86] The same month, a Connecticut paper reported that Universal was building a "jungle bungalow" for Joe Martin with indoor plumbing and "period furniture".[87] This building may have been used as a film set for A Monkey Movie Star, which was released the following year and was said to be Joe Martin's "autobiography".[88][89] Another article mentioned that Joe Martin's "jungalow" included a bed, a sunken bathtub, a horizontal bar, and a trapeze.[90] In March, Universal Syndicate distributed the first of the racist[91] Joe Martin comic strips drawn by Forest McGinn,[92] which were intended to establish Joe Martin as a multi-platform brand.[93]

Joe Martin was lent out by Universal to costar in an adventure film, The Revenge of Tarzan. Charlie the Elephant, another Universal City Zoo animal, was also credited as a performer in the movie.[94] While doing publicity for the film in August, Gene Pollar reported that Joe Martin had attacked him on set.[94][95] According to Pollar, "We were jumping...from bough to bough. I made a leap and, as my weight released it, a bough snapped back and hit Joe, standing ready to follow me, in the face. He thought I had done it on purpose...and the first thing I knew he was after me and on my back ready for fight. It took some effort to pull him off and it took triple the amount of effort and all the pastry in my lunch box to put him in friendly humor with me again."[94]

Joe Martin reportedly spent the summer with the Ringling circus "where he and Congo, a negro advertised as an African bushman, occupied a sideshow cage together."[22]

In a December 1920 news article, Joe Martin was said to have displayed chivalrous instincts.[96] While filming a scene in which his character was meant to assist the villain in stealing from the heroine, Joe Martin entered the situation to find the villain looming over her: "...Joe seized the villain with his long, powerful arms and pulled his legs from under him. The villain fell to the floor with a startled cry for help, and Stecker had to explain to the trained orangutan that the threatening attitude was all in the picture."[96][97]

1921: Continuing in show business, Ethel Stecker incident

[edit]In 1921, an advertisement for A Wild Night noted, "Mr. Martin has had a longer career on the screen than any other real monkey."[98] His owners reportedly had a $25,000 (equivalent to $427,052 in 2023) life insurance policy on Joe Martin,[22][99] and he was said to receive monthly veterinary health assessments.[22] At this time, Joe Martin reportedly earned his owners $500 a week appearing in vaudeville and $1,200 appearing in non-Universal films.[22]

In February 1921, Universal released a one-reel short, No Monkey Business, that depicted Martin arriving home from a night at the club, acting drunk.[100]

During this period Curley Stecker reported that he sometimes climbed onto the roof of Joe Martin's cage and looked "down at him through the grating to see how he occupied his leisure moments. Unobserved, Joe acts with the same dignified decorum which characterizes his moments before the camera."[9] Stecker reported that Joe Martin usually remained at the back of his cage unless someone passed by, and then he would come to the front and reach his hand out in greeting. Favored visitors were offered milk. Joe Martin exhibited annoyance by retreating to his bedroom and covering his head with a blanket. When he was "furiously enraged", he would swing on his monkey bars until "his pent-up feelings [had] been relieved."[9] In a story about their visit to Edgar Rice Burroughs' ranch,[j] Stecker said: "Joe was the first to alight and shook hands cordially with the naturalist. After a walk through the house we went to the dinner table. Joe will insist on tying his napkin around his neck, but aside from that slight breach of etiquette, everything went smoothly. What surprised Mr. Burroughs most was Joe knew immediately which knife and fork to use for each course."[9]

Three juvenile orangutans, said from to have come from Borneo in crates stuffed with "jungle grass," joined the Universal City menagerie around March 1921.[102] Two, called Jiggs[k] and Kelly, had their own enclosure with a "heat plant" and wore "little pneumonia jackets of flannel Mrs. Stecker has made for them."[22][l]

Stecker mentioned to a reporter that Joe Martin's "first rampage lasted a week, in which time he took a gun away from one of the policemen who was attempting to catch him and was about to kill the cop when the rest of us were able to seize him and truss him."[9] According to another account of the incident, the police officer had tried to shoot Joe Martin first.[28]

In June 1921, Joe Martin may have bitten Ethel Leona Stecker (née Spurgin), the wife of Curley Stecker,[104] while shooting A Monkey Bellhop, and had his canines removed or filed down as a consequence.[46] According to a newspaper report, after being startled or confused or hit with a telephone thrown by Curley Stecker, or all three, Joe Martin bit into Ethel Stecker's ankle "down to the bone". The legally prescribed consequence for an animal bite was supposed to be death for the animal, but Ethel Stecker pleaded for Joe Martin's life: "I brought him from a baby, I couldn't bear to part with him." Curley Stecker reportedly "appealed to authorities, promising to saw off his tusks if he would be spared."[46] Joe Martin was also considered a lucrative profit generator for the studio and much too valuable to be shot.[85] It is unclear if any dental surgery took place. This story was retold in silent-era child performer Diana Serra Cary's memoir about 75 years later.[85][105]

Joe Martin's second reported assault on a woman took place while he was on loan to First National. Joe Martin apparently threw a coconut at actress Dorothy Phillips' head, and laughed about it afterward. Phillips was saved from injury by the density of her wig.[106]

In October 1921, the Los Angeles Herald discussed a possible legal issue related to Joe Martin's mail:

Joe gets about a dozen letters a day from all over the world, most of his correspondents being under the impression that he is 'a little man dressed up like a monkey.' It is the reverse. He is a little monkey dressed up like a man, to be more exact, a 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m) orang-outang with a human brain. Inspector Cookson of the Los Angeles office of the postal inspectors is interested in determining Joe's rights to his own mail under the postal laws. Technically Joe is an animal. Actually he is an animal with a human brain and people write to him under perfectly good 2-cent stamps. Just to avoid any encounter with the federal grand jury Stecker has just instructed Joe Martin to open his own mail. It is a regular morning ceremony now at the Universal City arena.[107]

The possible legal issue centered around fans sending money orders to pay for photos of Joe Martin; if "Stecker should cash the money order on behalf of Universal it would take Edwin Loeb[m] and a whole battery of famous corporation lawyers to keep him out of the clink."[109] When handed a stack of envelopes from his mailbag, Joe Martin would usually pick the one with the "brightest hue" or the one with the most postage stamps; he then would hold it up to the light and rip off the end of the envelope, careful not to tear the enclosed contents.[109]

In November 1921, as part of a studio-wide restructuring, Curley Stecker was removed as head of the Universal City Zoo.[110]

1922–1923: Behavioral issues, death of Curley Stecker

[edit]

In spring 1922, The San Francisco Call reported that Joe Martin's film career was nearing an end: "Some think Joe Martin is incurably insane...when Joe showed signs of melancholia over Stecker's absence, a little monkey was placed in his cage in hopes that the companionship would stop his brooding. Joe beat the monkey to death against the bars."[111] Joe Martin also attacked three substitute trainers while Stecker was elsewhere.[112] Stecker was rehired after an "absence of several months".[112][113] When Stecker reentered Joe Martin's cage for the first time, the orangutan first verified his identity by checking that this man was missing part of a finger (which Stecker had lost to an accident), and then he "threw hairy arms around Stecker's neck and kissed him."[112] Around the same time, magazine writer Emma-Lindsay Squier published a book about animals subtitled Adventures in Captivity; one chapter is entirely devoted to Joe Martin, whom Squier regarded highly. Squier wrote that Joe Martin adored his trainer "Pudgy" and despised his past trainer "Red Gallagher," who had once whipped him and burned him with a hot poker. In "Joe Martin, Gentleman!", Squier documented two additional assaults; she also witnessed Joe Martin defend a weaker animal from a bully, rescue an endangered human baby, and earn the respect of his sworn enemy.[17]

During the filming of Trifling Women (1922), there was another altercation. Joe Martin played a sidekick of Barbara La Marr's character; Joe Martin and La Marr got along well, and Joe Martin did not react well when La Marr had scenes with her human male costars.[114] Joe Martin bit his costar Edward Connelly while they were shooting a scene where Connelly's character put a necklace around La Marr's neck.[115] Emma-Lindsay Squier reported that he had worked all day and "far into the night" and that "the nature of the scene was a constant tantalization to him" as it involved Edward Connelly taking away "a string of pearls given him in play by the heroine".[42] A different account claims that Joe Martin was irritated at being refused a tumbler of water that Connelly was drinking, and that he almost knocked over La Marr to get to Connelly.[79][116] A report in Photoplay stated that Stecker had told Connelly not to give Joe Martin the water because "he only drinks warm water and it's not good for him." Joe Martin waited until Stecker's back was turned to leap at Connelly; it took Stecker and three property men a full 10 minutes to get Joe Martin off Connelly.[117] Joe Martin drew blood,[114] possibly broke Connelly's arm and "mangled" his hand.[79][116] Film editor Grant Whytock later recalled, "It took three of us twisting [Joe Martin's] balls to make him let go."[115] During the Trifling Women incident Joe Martin apparently also bit Curley Stecker.[24][28] Stecker told Squier that even though he gave Joe Martin a "prompt and thorough beating after the unfortunate episode," Joe Martin did not seem to hold a grudge.[42] Cinematographer John F. Seitz used matte processing to finish the film's remaining scenes between Joe Martin's character Hatim-Tai and Connelly's Baron François de Maupin.[85]

In December 1922, Stecker discussed Joe Martin's mental health and changing behavior with the New York Tribune:

Well, [monkeys] develop a tendency to become grouchy as they get older. You take Joe Martin. He used to lead little children by the hand and be the ladies' pet. Now we daren't let one near him, ever since he carelessly fastened his teeth into the director of another company which rented him. We don't make him work when he doesn't feel like it. And that's most of the time lately, because his mind is fixed on getting married, and we have imported his bride at great expense [...] He's had his way too much, like some humans, and it's made him selfish and ornery; but with a spry young lady orang-outang in the cage it will be different.[118]

On April 23, 1923, while filming The Brass Bottle, Charlie the Elephant "went berserk".[33] Charlie "turned on his trainer...picked him up and dashed him to the ground. As Charlie tried to kneel on Stecker to crush him, a stagehand struck the enraged elephant with a pitchfork, and the trainer was rescued."[33] Stecker suffered lacerations, contusions, rib fractures, and a concussion.[119][120] Charlie the Elephant was euthanized in autumn 1923.[33][121] Stecker died the following year from leukemia, with "wild animal injury" listed as a complicating factor on his death certificate.[119] At the time of Charlie's attack on Curley Stecker, Joe Martin was already "regarded as insane".[122]

The studio wanted Joe Martin to appear in Merry-Go-Round (1923) but director Erich Von Stroheim refused to work with him.[123] After about a quarter of the movie had been filmed, producer Irving Thalberg fired Von Stroheim for several reasons, including "totally inexcusable and repeated acts of insubordination".[124] Von Stroheim was replaced by with Rupert Julian.[32] Joe Martin appeared in the film, but "virtually all of the footage of Joe in the picture has him by himself ... it's obvious that Universal ... strictly limited his interaction with other performers."[85] A review in The New York Times mentioned that the movie featured a "great orang-outang—too big, but made to appear very real."[125]

1923–1927: Barnes Circus and Barnes City Zoo

[edit]In November 1923, Charles B. Murphy replaced Curley Stecker as head animal trainer at Universal.[126] On December 31, 1923,[127] Joe Martin was sold to the Al G. Barnes Circus.[128] According to Camera!, Universal studio chief Carl Laemmle "reluctantly" consented to the sale "on the circus man's assurance that the big ape would always have a proper home and good treatment."[24] The deal was made by Harley Tyler, the Barnes Circus "fixer".[30][129] Universal claimed the price was $25,000 (equivalent to $447,070 in 2023).[128] In his memoir, Barnes said he paid $5,000.[30] The Ringling Brothers and other circuses had been offered the opportunity to buy Joe Martin but passed.[28] A 1950 article asserted that Barnes bought Joe Martin as a counter to Ringling's acquisition of the gorilla John Daniel II.[130][131] The studio magazine, Universal Weekly, reported that the sale was necessary because Joe Martin had "developed temperament and temper...a sudden savage sullenness which made it dangerous for any human actor to work with him."[128] Camera! reported, "Charles Murphy, the first man to put him in pictures, ushered him out of pictures, loading him into a cage on a circus truck".[24]

Joe Martin was at the studio for approximately a decade and for the most part remained in robust health, despite the historic fragility of captive orangutans.[10][28] In addition to his bout with influenza, he apparently once stole a spiked bowl of punch from a banquet scene and was ill for the remainder of the day; a day of filming where he continuously smoked a cigar made him similarly ill.[132] Joe Martin also suffered "Klieg eyes," a reaction to the brightness of the sound-stage lights.[28] He was spotted wearing an arm sling in 1919, supposedly because he fell off a roof and sprained his wrist.[133] Joe Martin also suffered electrical burns to his hands in 1919 after he escaped a film shoot, climbed a power pole, chewed on the rubber insulation of the copper wires, and then began swinging along the lines as if he were in a forest canopy. Universal City shut off the electricity, and assistant director Harry Burns climbed up the pole and rescued the "partially-paralyzed" animal.[134]

Early 20th-century American circus animals were broadly divided into two groups: the performing or working animals, such as elephants that appeared in the center ring and also hauled equipment, and the menagerie animals that had a more passive role as a sideshow attraction.[135] Joe Martin was likely a menagerie animal.[6][136] According to Bandwagon, Joe Martin "was billed by Barnes' show as monkey, chimpanzee, or gorilla, but seldom as an orang-utang which photos from those years prove he was."[129] Summers were spent touring western North America by rail; winters were spent at the Barnes Zoo in southern California.[137]

In 1924, Joe Martin's first year with Barnes, George Emerson, who had previously been employed by Universal Zoo, was responsible for his care.[129] Billboard reported that Joe Martin was being billed as "the greatest movie star of them all" and that "Dr. Gunning, who attends him, says he is in the pink of condition."[138] Lorena Hickok described Joe Martin as a "broken and discouraged monkey" in a "narrow cage under the canvas out on the hot, dusty, old circus lot".[77]

A 1925 news report claimed that "no fewer than four persons were constantly engaged in looking after Joe's comfort."[139] A later report clarified that Joe Martin's care probably involved three men holding a 2 in (5.1 cm)-thick iron chain attached to a collar around his neck.[140] A photograph of an orangutan with cheek pads baring his teeth at Al G. Barnes appeared in a March 1925 photo feature in the Los Angeles Times.[141] Around May 1925, Billboard reported that Joe Martin was the feature attraction of the Barnes menagerie and that a person named Joe Coleman was in charge of his education.[136] In June, in the presence of a group of reporters, Joe Martin dressed himself in a suit, struck a match, lit his own cigarette, and enjoyed a bottle of pop at the prompting of his trainer E.L. "Blacky" Lewis.[142]

In January 1926, a reporter visiting the Barnes Zoo mentioned that Joe Martin was "trying to tear his cage apart".[143] Joe Martin was still touring with Barnes during the summer circus season in 1926.[144] A Wisconsin newspaper reported that Joe Martin rode in the circus parade route with a guard and a chain around his neck.[145] Joe Martin wore a black suit and a plug hat for the parade and "he doffed this hat courteously to the crowds."[145] Joe Martin now weighed 180 to 190 pounds (82 to 86 kg), was as "strong as an ox," and was a "mean brute"—his keeper's hand had recently been bitten and was bandaged.[145]

Joe Martin briefly escaped during a 1927 circus stand in California. To the shock of the assembled crowd, he initially charged a group of stake drivers, but then, "in his ape-like slouching amble", changed direction and seized trapeze artist Babette Letourneau by the arms. Letourneau reportedly screamed and fainted. Former heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries was on the scene because he and another heavyweight boxer, Tom Sharkey, were doing an exhibition match as part of the show. As witnessed by an alleged 400 members of the circus troupe, Jeffries ran at Joe Martin bellowing "Let go there—" which led Joe Martin to drop LeTourneau. Jeffries then swung at Joe Martin with his right but missed and lost his balance, at which point Joe Martin jumped on his back, holding on with his hind feet. Jeffries then threw himself backwards to the ground, hard enough to knock the wind out of Joe Martin. Jeffries got back up, and Joe Martin did too, but, in the words of the sports-page writer, "this time Jeffries in his famous crouch was ready." Jeffries knocked down Joe Martin with a punch, and then clambered on top of him and beat him unconscious. The orangutan was returned to his circus wagon, and was largely uninjured "except for a cut and swollen eye...He is not so lively, however, and seems to be brooding."[140]

1928–1931: Last reports

[edit]The Barnes City zoo closed in 1927 and winter quarters were relocated further inland to Baldwin Park.[146] New language in Barnes advance ads of summer 1928 said that Joe Martin was "the most valuable zoological specimen in captivity today".[147] On January 5, 1929, Barnes sold his operation to American Circus Corporation.[146] Eight months later, in September 1929, American Circus sold Barnes and four other traveling circus brands to Ringling.[146] The combination of the debt-financed purchase and the post-Great Crash collapse in ticket revenue was devastating for the circus business generally[148] and John T. Ringling's fortune specifically.[149] Al G. Barnes died of pneumonia in July 1931.[150] (The Barnes brand continued to tour the country by railroad until 1938 when it was subsumed into Ringling.)[146]

Joe Martin resurfaced briefly in 1931 in a Time magazine film column calling him "innocent, obedient, [and] clever" and that he was sold "when he became unmanageable, began to annoy other Universal monkeys".[107] Time also reported that Joe Martin may have been bought to perform in The Murders in the Rue Morgue,[151] but the part ultimately went to two ape-costumed humans and, for close-ups, a chimpanzee from the Selig Zoo.[152]

In 1935, an Idaho publisher printed Al Barnes' memoirs, as told to author Dave Robeson, while Barnes was dying in the desert city of Indio, California.[30]

[Joe Martin] would wear a man's clothing and eat in a civilized manner, using his dishes and cutlery in the formal way. He was fond of whisky and cigars. As he strolled about the circus tent, walking upright like a man, puffing a cigar and swinging a cane, he attracted a lot of attention and proved to be a great drawing card...His bed was built for a human being and Joe comported himself like a man, sleeping in pajamas in apparent enjoyment...His act of expectorating was especially comical and he chewed tobacco as if it had been a lifetime habit...Joe was several times used to advertise automobiles, and the spectacle he made, sitting in the cars as if he owned them, provided great publicity for the automobile companies.[30]

— Dave Robeson, Al G. Barnes, Master Showman (1935), pp. 102–103

Barnes also tells of a rampage that ended in Joe Martin being punched out by a boxer, and of Joe Martin getting tangled in his own clothes while having an outburst.[30] The book's illustrations 360 and 361 are photos of Joe Martin (orangutan) in his circus-wagon cage, alternately shaking hands with Al Barnes and "alone, in a pensive mood".[30] There is a surviving poster in the Tibbals Circus Collection of the Ringling Museum that reads "Giant Gorilla Man: The Largest Specimen of its Kind in All the World featuring 'Joe Martin (himself)'".[153]

Given the Time report, 1931 is a conservative estimated year of death for Joe Martin. Joe Martin's estimated birthyear predates by five years the earliest historical record in the International Orangutan Studbook, but even with a most-conservative birth year of 1914 and most-conservative death year of 1927, Joe Martin may well have been one of the longest-lived orangutans in overseas captivity in the era that closed with the advent of modern recordkeeping.[1][10][154]

Filmography

[edit]

Joe Martin had reportedly appeared in over 100 movies by the end of 1919.[69] Joe Martin and the other animals of the Universal City Zoo were used in tropical adventure movies, historical epics, circus pictures, or simply to add a gothic element to melodramas or horror films.[33]

According to "noted animal director" William S. Campbell, two-reel comedy shorts with humans could be shot in eight to 10 days, while animal comedies took upwards of a month.[40] Campbell used live chamber music, played within hearing but out of sight of his ape performers in order to elicit appropriate facial expressions during emotional scenes.[155] According to the primary history of Century Comedies, William S. Campbell's shorts were likely the apogee of Joe Martin-centric comedic scenarios, resulting in a decline in quality, exhibitor reception, and revenue after Campbell left Universal to become an independent producer.[34] Nonetheless, Campbell's assistant director Harry Burns carried on the Joe Martin franchise for two more years, generating six more titles, apparently in close cooperation with Curley Stecker.[34]

"Joe Martin monkey picture" was a marketing hook for a spinoff series featuring the chimpanzee Mrs. Joe Martin; Joe Martin possibly appeared in one of the pictures.[34][85] According to Steve Massa, "It seems likely that the creation of the 'missus' was a way for the studio to insure a regular release schedule of monkey comedies as big money maker Joe Martin was getting more difficult to work with."[85][n]

Gallery

[edit]-

Monkey Stuff, directed by William Campbell

-

Monkey Stuff at the Strand Theater, New York

-

"Joe Martin Soliloquizes" advertisement

-

A Prohibition Monkey, and coming soon, A Wild Night

-

Harry Burns & Curley Stecker producing team, 1920

-

Full-page ad for Joe Martin in A Monkey Schoolmaster

-

Carl Laemmle Presents Mr. Joseph Martin a Monkey Movie Star

-

"Assisted by Charlie the Elephant"

-

Jazz Monkey three-sheet

-

A Monkey Hero, directed by Harry Burns

-

Universal marketing for Joe Martin comedies

-

Universal marketing for Joe Martin comedies

See also

[edit]- Orangutans in popular culture

- List of individual apes

- List of animals in film and television

- List of Universal Pictures films (1912–1919) and (1920–1929)

- List of film and television accidents

- List of largest non-human primates

- The Playhouse (1921), a comedy short in which Buster Keaton's character steps in for an escaped vaudeville orangutan

- The Chimp (1932), a Laurel and Hardy short about circus and film apes

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Buck, writing in 1939, "I brought Joe back before the [first] World War...Joe was only 18 in (46 cm) high when I captured him. Just a tiny baby, but very intelligent."[25] However, suggestions of Frank Buck's involvement may be misinformation. Ansel W. Robison told the Saturday Evening Post in 1953 that he had first met Frank Buck in 1915 (after Joe Martin's film career was already well underway). At that time, "There was nothing to link [Buck] to animals...except his modest taste for finches."[26]

- ^ Behrendt-Lévy Insurance Agency apparently underwrote much of the film industry's insurance in the early 20th century.[27]

- ^ This could potentially be the 1912 or 1915 Ocean Park pier fires.

- ^ Carl Laemmle purchased four nearby ranches for US$165,000.[14] Groundbreaking was in June 1914[14] and some 50 movies had already been filmed at Universal City when the grand opening was held on March 15, 1915.[14][29]

- ^ Emma-Lindsay Squier almost certainly created a pseudonym for this person or persons, as the "Pudgy" of her article is without question Curley Stecker.[citation needed]

- ^ The confirmed survivors, all in the public domain and available online, are Detective Duck and Lady Baffles, Seven Years Bad Luck, Merry-Go-Round, The Adventures of Tarzan and a newsreel. Man and Beast may be in the Museum of Modern Art collection, and Monkey Stuff may be held by the British Film Institute. See Joe Martin (orangutan) filmography citations for catalog references for the possibly extant films.

- ^ For more on Goodwin and his association with the entertainment industry see the Pet Historian blog[60] by University of Delaware professor Katherine C. Grier, the author of Pets in America (2006).

- ^ The "wolves" were most likely the zoo's Alaskan Malamutes and Siberian Huskies[78] that played wolves on film.

- ^ Carl Stecker was Curley's older brother and lived two houses down from him in Lankershim in 1920.[47] Carl Stecker worked as a Hollywood animal trainer well into the 1930s.[84]

- ^ In 1919, Edgar Rice Burroughs bought 550 acres (2.2 km2) of San Fernando Valley ranchland from Harrison Gray Otis. In later years, as the land was developed, residents voted to name their community Tarzana after Burroughs' Tarzan Ranch.[101]

- ^ American zoos frequently named apes Jiggs and/or Maggie after the main characters of the comic strip Bringing Up Father.[1]

- ^ The largest of the original three was called Moriarty.[103]

- ^ The Sterns and the Laemmles had long been clients of Edwin and Joseph P. Loeb's entertainment law-pioneering firm Loeb & Loeb.[108]

- ^ Mrs. Joe Martin titles include A Jungle Gentleman (1919), The Good Ship Rock 'n' Rye (1919), Over the Transom (1920), and A Baby Doll Bandit (1920). All of the Mrs. shorts were directed by Fred Fishback and costarred Jimmie Adams.[34]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e De Boer, Loebert E. M. (1982). "2. The Orangutan in Captivity". The Orang Utan: Its Biology and Conservation. Workshop on the Conservation of the Orang Utan. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789061937029. LCCN 82007722. OCLC 8408766 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Minarchek, Matthew (January 2018). "Plantations, Peddlers, and Nature Protection: The Transnational Origins of Indonesia's Orangutan Crisis, 1910–1930". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 6 (1): 101–129. doi:10.1017/trn.2017.18. eISSN 2051-3658. S2CID 158313584.

- ^ a b Boomgaard, Peter (1999). "Oriental Nature, its Friends and its Enemies: Conservation of Nature in Late-Colonial Indonesia, 1889–1949". Environment and History. 5 (3): 257–292. doi:10.3197/096734099779568245. ISSN 0967-3407. JSTOR 20723109. PMID 20429140.

- ^ Sherman, Julie; Voigt, Maria; Ancrenaz, Marc; Wich, Serge A.; Qomariah, Indira N.; Lyman, Erica; Massingham, Emily; Meijaard, Erik (November 4, 2022). "Orangutan killing and trade in Indonesia: Wildlife crime, enforcement, and deterrence patterns". Biological Conservation. 276: 109744. Bibcode:2022BCons.27609744S. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109744. ISSN 0006-3207. S2CID 253364450.

- ^ Wich, S.A.; Shumaker, R.W.; Perkins, L.; de Vries, H. (August 1, 2009). "Captive and wild orangutan (Pongo sp.) survivorship: a comparison and the influence of management". American Journal of Primatology. 71 (8): 680–686. doi:10.1002/ajp.20704. eISSN 1098-2345. PMID 19434629. S2CID 11013175.

- ^ a b Buck, Frank; Anthony, Edward; Fraser, Ferrin; Weld, Carol (2000). Lehrer, Steven (ed.). Bring 'em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 9780896725829. LCCN 99086898. OCLC 43207125.

- ^ Lowenstine, Linda J.; Osborn, Kent G. (2012). "Respiratory System Diseases of Nonhuman Primates". Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research. Vol. 2: Diseases (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 413–481. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-381366-4.00009-2. ISBN 978-0-12-381366-4. LCCN 2012471137. OCLC 823390255. PMC 7158299. S2CID 82362882.

- ^ Buitendijk, Hester; Fagrouch, Zahra; Niphuis, Henk; Bogers, Willy; Warren, Kristin; Verschoor, Ernst (March 24, 2014). "Retrospective Serology Study of Respiratory Virus Infections in Captive Great Apes". Viruses. 6 (3): 1442–1453. doi:10.3390/v6031442. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 3970160. PMID 24662675.

- ^ a b c d e f "Movie Facts and Fancies". Boston Evening Globe. Vol. XCIX, no. 143. May 23, 1921. p. 10. Retrieved 2022-11-15 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c Schwalbe, Maria; Unger, Julia; Belcher, Deborah (2007). "The History of Orangutans in Captivity" (PDF). Species Survival Plan: Orangutan Husbandry Manual. Chicago Zoological Society/Brookfield Zoo Center for the Science of Animal Welfare.

- ^ Bender, Daniel E. (2016). The Animal Game: Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 45 (older animals), 55 (A.C. Robinson), 60 (Buck wife re jungle), 81 (fibs, fabricated), 84 (Buck brand name), 95–114 (Buck media career), 134–138 (fairs). doi:10.4159/9780674972759. ISBN 978-0-674-97275-9. JSTOR j.ctv253f7pm. LCCN 2016017880. OCLC 961185120. S2CID 197858007.

- ^ Cribb, Robert B.; Gilbert, Helen; Tiffin, Helen (2014). "7: Orangutans on Stage and Screen". Wild Man from Borneo: A Cultural History of the Orangutan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8248-4026-6. JSTOR j.ctt6wqz60. LCCN 2013031367. OCLC 878078682.

- ^ a b c Smith, Jacob (2012). The Thrill Makers: Celebrity, Masculinity, and Stunt Performance. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-520-27088-6. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1pnk67. LCCN 2020759094. OCLC 757476572.

- ^ a b c d Dick, Bernard F. (1997). "Chapter 2. The City Founder". City of Dreams: The Making and Remaking of Universal Pictures. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813120164. LCCN 96040094. OCLC 47011130.

- ^ Johnston, R. J. (1981). "The Political Element in Suburbia: a Key Influence on the Urban Geography of the United States". Geography: Journal of the Geographical Association. 66 (4): 286–296. ISSN 0016-7487. JSTOR 40570435.

- ^ Ancrenaz, M.; Gumal, M.; Marshall, A.J.; Meijaard, E.; Wich, S.A.; Husson, S. (2018) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Pongo pygmaeus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. e.T17975A123809220. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T17975A17966347.en. Retrieved 2022-11-20. ISSN 2307-8235

- ^ a b c d Squier, Emma-Lindsay (1922). "Joe Martin, Gentleman!". On Autumn Trails: And Adventures in Captivity. Cosmopolitan Book Corporation. pp. 170–194. LCCN 23013282. OCLC 1019536490 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "Entertainment page, no title, column 6". Boston Post. December 15, 1920. p. 11. Retrieved 2022-11-15 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Wallace, John B. (December 25, 1920). "Training Animal Actors for the Pictures". Dearborn Independent. Dearborn, Michigan. p. 13. Retrieved 2022-11-15 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Singleton, I.; Wich, S.A.; Nowak, M.; Usher, G.; Utami-Atmoko, S.S. (2018) [errata version of 2017 assessment]. "Pongo abelii". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. e.T121097935A123797627. doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2017-3.rlts.t121097935a115575085.en. ISSN 2307-8235.

- ^ Nowak, M.G.; Rianti, P.; Wich, S.A.; Meijaard, E.; Fredriksson, G. (2017). "Pongo tapanuliensis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. e.T120588639A120588662. doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2017-3.rlts.t120588639a120588662.en. ISSN 2307-8235.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Meeting the Animal Actors: Continuing My Adventures in Screen Land". The Kansas City Star. Vol. 41, no. 212. Kansas City, Missouri. April 17, 1921. p. 10C. ISSN 0745-1067. Retrieved 2022-12-02 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sherman, Julie; Ancrenaz, Marc; Meijaard, Erik (June 1, 2020). "Shifting apes: Conservation and welfare outcomes of Bornean orangutan rescue and release in Kalimantan, Indonesia". Journal for Nature Conservation. 55: 125807. Bibcode:2020JNatC..5525807S. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125807. ISSN 1617-1381. S2CID 216469035.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Universal Monkey Hailed from Singapore; Was Venice Attraction at One Time". Camera!. Vol. VI, no. 41. January 26, 1924. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-11-08 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ Buck, Frank; Weld, Carol (1939). "XII: All-Star Cast". Animals Are Like That!. New York: R.M. McBride and Co. LCCN 39029436. OCLC 498860552 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Morse, Ann (August 29, 1953). "They Sell People to Pets". Saturday Evening Post. Vol. 226, no. 9. pp. 32–33. Retrieved 2023-02-18 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Sam Behrendt Collection, ca. 1870–1920". Online Archive of California. Archived from the original on 2022-11-08. Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Joe Martin, Famous Ape of Movies, Ends His Long Screen Career". San Antonio Express. Vol. LXI, no. 62. San Antonio, Texas. March 24, 1924. p. 20. ISSN 2640-1061. Retrieved 2022-11-15 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "The Strangest City in the World: A Town Given Over to the Motion Picture". Scientific American. Vol. CXIL, no. 16. April 17, 1915. p. 365. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robeson, Dave (1935). "VI. ("Monkeys"); photo illustrations". Al G. Barnes, Master Showman, as told by Al G. Barnes. Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers, Ltd. pp. 88–105, 257. LCCN 35012032. OCLC 598387.

- ^ ""Jerry" Barnes with Universal". The Billboard. Vol. 26, no. 23. June 6, 1914. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b Braff, Richard E. (1999). The Universal silents: a filmography of the Universal Motion Picture Manufacturing Company, 1912–1929. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 9780786402878. LCCN 98003272. OCLC 38738742.

- ^ a b c d e f g Soister, John T.; Nicolella, Henry; Joyce, Steve (2012). American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913–1929. McFarland. pp. 48 (Black Orchids), 71 (Stecker, elephant), 576–577 (Joe Martin career). ISBN 9780786435814. LCCN 2011048184. OCLC 765485998. Retrieved 2022-10-19 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e Reeder, Thomas (2021). Time is money! : the Century, Rainbow, and Stern Brothers comedies of Julius and Abe Stern. Orlando, Florida: BearManor Media. pp. 133–145 (Joe Martin, Mrs. Joe Martin, William Campbell, Harry Burns, Diana Cary memoir), 839–842 (Filmography appendix: Joe Martin comedies). ISBN 9781629337982. OCLC 1273678339.

- ^ "Joe Martin Turns 'Em Loose display ad". Moving Picture World and View Photographer. Vol. 15. World Photographic Publishing Company. September 11, 1915. p. 1766. Retrieved 2022-10-19 – via Google Books.

- ^ "In Nagana Universal uses a..." Los Angeles Daily News. Vol. 10, no. 147. February 21, 1933. p. 13. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Balducci, Anthony (2012). The Funny Parts: A History of Film Comedy Routines and Gags. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 46. ISBN 9780786488933. OCLC 768119702.

- ^ "Universal Program - Animals of the Jungle". Motography. Vol. XIV, no. 22. November 27, 1915. p. 1162. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "Becomes a Star in a Night Due to Beauty and Talent: Universal Film Star, Chimpanzee Charlie, Shows Remarkable Histrionic Ability and Signs Life Contract". The Elyria Chronicle. Vol. 11, no. 3527. Elyria, Ohio. November 30, 1915. p. 7. Retrieved 2022-12-06 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Birds, Beasts and Trees: In Search of the White Rhinoceros". The Literary Digest. 66 (13). Funk & Wagnalls: 96–123 (Joe Martin, 106–107). September 25, 1920. ISSN 2691-3135. Retrieved 2022-10-19 – via Google Books.

- ^ Buck, Frank; Weld, Carol (1939). Animals are like that!. New York: R.M. McBride and Co. p. 208. hdl:2027/uc1.31210013456981. Retrieved 2023-08-10 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b c Squier, Emma-Lindsay (July 9, 1922). "Meet Filmdom's Animal Stars: Teddy, Pepper and Snooky Face Interviewer". Los Angeles Times. Vol. LXI. pp. III13, III18. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 161197996. Retrieved 2022-12-04 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Casts of the Week – A Monkey Fireman". Camera!. Vol. 3, no. 39. January 8, 1921. p. 18. Retrieved 2022-11-27 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b Lauritzen, Einar; Lundquist, Gunnar; Spehr, Paul; Dalton, Susan; Long, Derek. "Man and Beast". Early Cinema Titles, 1908–21. Media and Cinema Studies Department, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 2022-11-23 – via ECHO (Early Cinema History Online).

- ^ "Production Notes Among Studios Week Beginning Today". Camera!. Vol. II, no. 34. November 29, 1919. p. 5. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b c "Playhouse Gossip". Lansing State Journal. Vol. 66. June 3, 1921. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-12-03 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Algerman Stecker, 1920". United States Census, 1920, database with images. January 31, 2021. Retrieved 2022-12-04 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ "Father time deals a cruel hand to some of us, especially those undeserving of cruelty". Hollywood Filmograph. Vol. 10, no. 27. July 19, 1930. p. 19. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "Universal Moviegrams". Calgary Herald. Vol. 43, no. 4728. July 17, 1926. p. 7. Retrieved 2022-12-07 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Flivver Manufacturer Visits Universal". The Moving Picture World. Vol. 30, no. 1. Chalmers Publishing Company. October 7, 1916. p. 59 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Universal Animated Weekly NAID: 92130 Local ID: FC-FC-2139 Moving Images 1 Video". National Archives Catalog. Motion Picture Films Relating to the Ford Motor Company, the Henry Ford Family, Noted Personalities, Industry, and Numerous Americana and Other Subjects. 1916. Retrieved 2022-12-09.

- ^ "Church Dignitaries in Universal Animated Weekly". Moving Picture World. Vol. 25, no. 12. November 18, 1915. p. 2017 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ Campbell, William S. (September 7, 1919). "Directing Animal Actors". Vancouver Daily Sun. Vol. 35, no. 243. Vancouver, British Columbia. p. 18. Retrieved 2022-12-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Janitor Wins Year's Contract for Beery". The Moving Picture Weekly. Vol. 3, no. 1. Moving Picture Weekly Pub. Co. July 1, 1916. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Stories of the One-Reel Photoplays". The Moving Picture Weekly. Vol. 3, no. 16. Moving Picture Weekly Pub. Co. December 2, 1916. p. 36. Retrieved 2022-12-11 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ Marple, Albert (April 1916). "Making Pictures in California". Motion Picture Classic. Vol. 2, no. 2. M.P. Publishing Company. pp. 37–39. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Lena's Favorite Playmate". The Moving Picture Weekly. Vol. V, no. 1. Moving Picture Weekly Pub. Co. August 18, 1917. p. 17. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Child Gets Goods on Famed Movie Monkey". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLII, no. 53. January 2, 1917. p. 19. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Koszarski, Richard (2005). "Flu Season: "Moving Picture World" Reports on Pandemic Influenza, 1918-19". Film History. 17 (4): 466–485. doi:10.2979/FIL.2005.17.4.466. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 3815547. S2CID 191444910.

- ^ Grier, Katherine C. (Kasey) (February 23, 2017). "Richard Goodwin, Dog Specialist, Part II". The Pet Historian. University of Delaware Department of History. Retrieved 2022-11-02.

- ^ a b "$10,000 Orang-Outang Has Narrow Escape from Flu". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLIV, no. 2. November 4, 1918. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-11-02 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ a b "Orang-Outang Fights 'Flu'". The Moving Picture Weekly. Vol. 7, no. 14. Moving Picture Weekly Pub. Co. November 23, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "Movie Facts and Fancies". Boston Evening Globe. Vol. C, no. 116. October 24, 1921. p. 13. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved 2022-11-20 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Los Angeles Notes". The Billboard. Vol. 30, no. 46. November 16, 1918. Retrieved 2022-10-18 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "News & Notes: The House of Granger". Pictures and the Picturegoer. 14 (223). London: 483. May 18, 1918. ProQuest 1771218707.

- ^ "Film Ape Lovable, Is Testimony in Suit for 40 Bites". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLIV, no. 36. December 13, 1918. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Squier, Emma-Lindsay (July 1920). "He Likes 'Em Wild". Photoplay. Vol. XVIII, no. 2. pp. 78, 94. ISSN 0732-538X. Retrieved 2022-11-10 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b "Joe Martin Says". Photoplay. Vol. XVI, no. 2. July 1919. p. 46. ISSN 0732-538X. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b Squier, Emma-Lindsay (November 1919). "In a Movie Menagerie". Picture-Play Magazine. Vol. XI, no. 3. pp. 35–37. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "Display ads: Joe Martin This is Me – Joe Martin's Diet – Strand Theater Jazz Monkey". Brandon Daily Sun. Vol. XXI, no. 245. Brandon, Manitoba. October 16, 1919. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Exhibitors to Govern". The Washington Post. No. 16028. May 2, 1920. p. 3. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-12-03 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Wid's Filmdom (Apr–Sep 1919) – Lantern". lantern.mediahist.org. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ "Joe Martin Soliloquizes display ad". The Moving Picture Weekly. Vol. 8, no. 24. Moving Picture Weekly Pub. Co. August 2, 1919. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-12-09 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b "Herald News Boys Guests at Theater". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLIV, no. 221. July 17, 1919. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ a b c d "Sure He Can Drive a Car". Los Angeles Times. Vol. XXXVIII. July 24, 1919. p. VI-6. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 160677624. Retrieved 2022-12-05 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Screen Squibs". Cincinnati Commercial Tribune. Vol. XXIV, no. 15. June 29, 1919. pp. 23–24. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b Hickok, Lorena A. (June 15, 1924). "Joe Martin, Once Movie Star, Sulks in Circus Den: 'Largest Orang-outang in Captivity' for Years Romped Before Camera in Shiek [sic] Waistcoats and Confounded Fundamentalists, Then 'Went Bad'". Star Tribune. Vol. 58, no. 22. Minneapolis, Minnesota. p. 7. ISSN 0895-2825. Retrieved 2022-12-03 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Baby Wolves at Universal Zoo". The Moving Picture Weekly. Vol. 4, no. 14. May 19, 1917. p. 35. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b c "Orang-Outang Runs Amuck and Frees Elephant, Wolves". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLIV, no. 231. July 29, 1919. p. 11. Retrieved 2022-11-14 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Gould (June 29, 1919). "Close-Ups and Cut-Outs". Omaha Daily Bee. Vol. XLIX, no. 2. Omaha, Nebraska. p. 22. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "From Cinema Studios". Anaconda Standard. Vol. XXX, no. 320. Anaconda, Montana. July 20, 1919. p. 29. Retrieved 2022-11-19 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Burns, Harry (November 1, 1919). "Chit, Chat and Chatter of Interest". Camera!. Vol. 2, no. 30. p. 5. Retrieved 2022-12-04 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Malice? No!". San Luis Obispo Tribune (Weekly). Vol. 61, no. 45. January 9, 1920. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-11-14 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ "Alaskan Dog Fight Halts 'Klondike Lou'". The Indianapolis Times. January 9, 1936. p. 10. ISSN 2694-1872. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Chronicling America (Library of Congress).

- ^ a b c d e f g Massa, Steve (November 18, 2022). Lame Brains and Lunatics 2: More Good, Bad and Forgotten of Silent Comedy. BearManor Media. pp. n.p.

- ^ Kaempffert, Waldemar, ed. (March 1, 1923). "Want to Be a Movie Star, Fido? We'll Show You How". Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 96, no. 3. Bonnier Corporation. pp. 51–52. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Joe Martin to Have New Bungalow". The Bridgeport Times. Vol. 15, no. 60. Bridgeport, Connecticut. March 11, 1920. p. 13. Retrieved 2022-11-19 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Spectacular Version of Love Romance of Queen of Sheba Joins Novelties on the Screen: The Oath and A Small Town Idol Are Other New Films". New York Herald. Vol. LXXXV, no. 223. April 10, 1921. p. 32. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Remodeled from Pit to Dome, Loew's State on Broadway Opens Today". Salt Lake Telegram. Vol. XX, no. 78. Salt Lake City, Utah. April 17, 1921. p. 18. Retrieved 2022-11-18 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Squier, Emma-Lindsay (June 1920). "'Married? Sure, But I Wish I Weren't' So Said Joe Martin, in a Most Amazing Interview". Picture-Play Magazine. Vol. XII, no. 4. pp. 54, 86. ISSN 2693-0250. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jahre, Ben; McGinn, Emily (July 16, 2015). "Will the Real Joe Martin Please Stand Up?". Lafayette College Library Reference Services. Easton, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2022-11-22.

- ^ Schuddeboom, Bas; Kousemaker, Kees (July 14, 2016). "Forest A. McGinn". Lambiek Comiclopedia. Amsterdam: Lambiek Comic Shop. Archived from the original on 2022-10-17. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ "Comic Strip Boosts Monk: Universal Issues Cartoons to Exploit Joe Martin, Monkey-Actor". Motion Picture News. Vol. XXI, no. XV. April 3, 1920. p. 3096. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b c "At the Palace". Morning Press. Vol. 49, no. 283. Santa Barbara, California. August 14, 1921. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ "The Return of Tarzan". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2022-11-15.

- ^ a b Dingle, Cornelia (December 12, 1920). "Monkey Shines as 'Man,' While Man Apes 'Monkey'". Boston Post. p. 51. Retrieved 2022-12-04 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Villain Attacked by Ape, When Girl Threatened by Him - Simian Matinee Idol of the Zoo, Used in Picture, Proves Chivalrous". Great Falls Daily Tribune. Vol. 32. Great Falls, Montana. June 13, 1920. p. 32. Retrieved 2022-12-11 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Court Theatre display ad". Carroll County Democrat. Vol. 35, no. 5. Huntingdon, Tennessee. February 25, 1921. p. 5. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Chronicling America (National Endowment for the Humanities, Library of Congress).

- ^ Burns, Harry. "Camera! – Lantern". lantern.mediahist.org. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ Gary D. Rhodes, David J. Hogan (2022). The Palgrave Encyclopedia of American Horror Film Shorts: 1915–1976. Springer Nature. p. 140. ISBN 9783030975647.

- ^ "History of Tarzana". Tarzana Neighborhood Council. Archived from the original on 2022-08-03. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ "Joe Martin a Guardian". Los Angeles Times. Vol. XL. March 6, 1921. p. II-7. ProQuest 160904232. Retrieved 2022-12-05 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Foreign Film Stars To Be Seen in Comedies". Evening Vanguard. Vol. XXVI, no. 91. Venice, California. April 18, 1921. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-12-06 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Algernon S Stecker and Ethel L Schroeder, 1917". California, County Marriages, 1850-1952. Retrieved 2023-01-13 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ Cary, Diana Serra (1996). Whatever happened to Baby Peggy? : the autobiography of Hollywood's pioneer child star. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 44–46 (deaths of Martin, Stecker, elephant), 335 (Life in Hollywood newsreel). ISBN 0-312-14760-0. LCCN 96023290. OCLC 34772308.

- ^ "Murrette". Richmond Palladium. Vol. XLVI, no. 137. Richmond, Indiana. April 20, 1921. p. 18. Retrieved 2022-12-01 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "Orang-Outang Jazzes Mail Law". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLVI, no. 306. October 24, 1921. p. B12. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Selvin, Molly (2015). "The Loeb Firm and the Origins of Entertainment Law Practice in Los Angeles, 1908–1940" (PDF). California Legal History. 10. California Supreme Court Historical Society: 135–173.

- ^ a b "Joe Martin Now Opens Own Mail". Los Angeles Times. Vol. XL. October 30, 1921. p. III-39. ProQuest 161000416. Retrieved 2022-12-05 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Shakeup at U". Los Angeles Herald. November 21, 1921. Retrieved 2023-01-12 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ "Gossip of Screenland by Wood Holly Joe Martin's Screen Career May Be Over". The San Francisco Call. Vol. 111, no. 80. April 8, 1922. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ a b c "Joe Martin Welcomes Trainer With a Kiss". Los Angeles Evening Express. March 10, 1922. p. 20. Retrieved 2022-12-03 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pickups by the Staff". Camera!. Vol. IV, no. 49. March 8, 1922. p. 16. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Snyder, Sherri (2017). "18". Barbara La Marr: The Girl Who Was Too Beautiful for Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813174259. OCLC 974454308.

- ^ a b Soares, André (2010). Beyond Paradise: The Life of Ramon Novarro. University Press of Mississippi. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-60473-458-4. OCLC 1298206162.

- ^ a b "Movie Mishaps and Tragedies Never on the Silver Screen". San Antonio Express. Vol. LIX, no. 272. San Antonio, Texas. September 24, 1924. p. 62. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Plays and Players". Photoplay. Vol. XXII, no. 2. July 1922. p. 62. Retrieved 2022-12-09 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ Toombs, Maud Robinson (December 10, 1922). "Quadruped School of Dramatic Art". New York Tribune. pp. 13, 15. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via Chronicling America (National Endowment for the Humanities, Library of Congress).

- ^ a b "Algernon M Stecker, 1924". California, County Birth and Death Records, 1800–1994. FamilySearch. March 1, 2021. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Trainer Injured When Mad Elephant Charges". Motion Picture News. May 3, 1923. p. 2152. Retrieved 2022-11-24 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "'Charley' Pays for Bad Temper with His Life". San Pedro Daily News. Vol. XXI, no. 208. October 4, 1923. p. 6 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ "From the Studios". The Kansas City Star. Vol. 43, no. 224. April 29, 1923. p. 85. ISSN 0745-1067. Retrieved 2022-12-31 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Koszarski, Richard (2001). Von: The Life and Films of Erich Von Stroheim. Limelight Editions. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-87910-954-7. LCCN 00048380. OCLC 45044227. Retrieved 2022-10-19 – via Google Books.

- ^ Flamini, Roland (1994). Thalberg : the last tycoon and the world of M-G-M. New York: Crown Publishers. pp. 33–36. ISBN 0-517-58640-1. LCCN 93002523. OCLC 28336345.

- ^ "The Screen: The Clown and His Daughter" (PDF). The New York Times. July 2, 1923. p. 16. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 103182662. Retrieved 2022-10-28.

- ^ "Screen Stars and Films". Auckland Star. Vol. LIV, no. 287. December 1, 1923. p. 23. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Movie Monkey Sold". Bakersfield Californian. Vol. XXXVI, no. 132. January 1, 1924. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-11-18 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c "Joe Martin, Noted Monkey, Leaves Screen for Circus". Universal Weekly. Vol. 18, no. 24. Moving Picture Weekly Pub. Co. January 26, 1924. pp. 11 ($25K), 32 (farewell party) – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Chang (September–October 1985). "The Al G. Barnes Wild Animal Circus: 1924". Bandwagon: Journal of the Circus Historical Society. 29 (5): 4–13. ISSN 0005-4968. Retrieved 2022-11-29 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Smith, A. Morton (February 1, 1950). "Circusiana : Famous Circus Animals". Hobbies: The Magazine for Collectors. Vol. 54, no. 12. Chicago: Otto C. Lightner Publishing Company. p. 27. Retrieved 2022-11-19 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Willoughby, David P. (1978). "Some distinguished captive gorillas". All about gorillas. South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes. ISBN 0-498-01845-8. LCCN 76050215. OCLC 3444989 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Celluloid Celebrities". Film Fun. Vol. 31, no. 366. October 1919. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 2022-12-14 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "Theater Notes". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLIV, no. 220. July 16, 1919. p. 23. Retrieved 2022-11-18 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ "U's Trick Orang-Utang Comes Near Death". Los Angeles Times. Vol. XXXVIII. March 30, 1919. p. 37. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2022-12-03 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Nan, Stewart (2000). "Cleveland, 1942: The Ringling Menagerie Fire". The Circus Fire: A True Story. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385496841. LCCN 99042051. OCLC 42049262.

- ^ a b "Complete Review of Al G. Barnes' Circus". The Billboard. Vol. 37, no. 15. April 11, 1925. p. 118. Retrieved 2022-11-28 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ Borders, Gordon (July–August 1967). "Famous Circus Landmarks: Al G. Barnes Winter Quarters at Culver City, Calif". Bandwagon: Journal of the Circus Historical Society. 11 (4): 10–12. Retrieved 2022-12-09.

- ^ "Under the Marquee by Circus Cy". The Billboard. Vol. 36, no. 20. May 17, 1924. p. 74. Retrieved 2022-10-17 – via Internet Archive, Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "Famous Movie Star Coming Joe Martin Joins a Circus". The Kennewick Courier-Reporter. Vol. XII, no. 17. Kennewick, Washington. July 23, 1925. p. 1 – via Chronicling America (National Endowment for the Humanities, Library of Congress).

- ^ a b "Jeffries K.O.'s Huge Gorilla in Half-Hour Hunt – Joe Martin, Gorilla Man, Goes Down for Count – Mighty Jeff Stages the Greatest Battle of His Life". The Marysville Appeal. Vol. 132, no. 112. May 11, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved 2022-12-03 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Elephants 'n' Everything". Los Angeles Times. March 15, 1925. p. J4. ProQuest 161653524. Retrieved 2022-12-04 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Darwin Was Right, Visitors Seeing Circus Monkey's Clever Antics Agree". Calgary Albertan. Vol. 24, no. 83. June 6, 1924. p. 14. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Read, Kendall (January 31, 1926). "Winter Home of Circus Holds Thrills Galore: Quarters of Al G. Barnes Show Teem With Activity as Crews Prepare for New Season on Road; Animals Furnish Center of Interest; Secrets of Sawdust Ring". Los Angeles Times. p. D3. ProQuest 161820466. Retrieved 2022-12-05 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Al G. Barnes Big 4 Ring Circus Will Exhibit Afternoon and Night at Red Lodge on July 1". The Carbon County News. Vol. 3, no. 15. Red Lodge, Montana. June 24, 1926. p. 4. Retrieved 2022-12-08 – via Chronicling America (National Endowment for the Humanities, Library of Congress).

- ^ a b c "Barnes Circus Goes Over Successfully; Everyone Tickled". The Chippewa Daily Herald. August 18, 1926. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-12-02 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Bradbury, Joseph T. (July–August 1963). "The Al G. Barnes Winter Quarters at Baldwin Park, Calif". Bandwagon: Journal of the Circus Historical Society. 7 (4): 3–6. ISSN 0005-4968. Retrieved 2022-11-21 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Monkey Business". Perry Daily Journal. Vol. VIII, no. 144. Perry, Oklahoma. September 21, 1928. p. 3. Retrieved 2022-11-20 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Khan, Gulnaz (May 17, 2017). "The Death of One of the Oldest Shows on Earth". National Geographic. ISSN 2589-3114. Archived from the original on 2022-12-01. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ Standiford, Les (2021). Battle for the Big Top: P.T. Barnum, James Bailey, John Ringling, and the Death-Defying Saga of the American Circus. New York. pp. 246–253, 258–261. ISBN 978-1-5417-6228-2. LCCN 2020056749. OCLC 1199127731.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Rasmussen, Cecilia (September 29, 2002). "L.A. Then and Now: Cagey Entertainer's Life Was a 3-Ring Circus; Al G. Barnes created an L.A. amusement mecca. He was nearly as famous for his shenanigans outside the big top". Los Angeles Times. pp. B4. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 421749658. Archived from the original on 2022-11-21. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ "Cinema: The New Pictures". Time. Vol. 18, no. 14. October 5, 1931. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on 2022-11-20. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ Taves, Brian (October 24, 2022). "Universal's Tradition of Horror: Murders in the Rue Morgue". American Cinematographer. ASC Staff. American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on 2022-11-20. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ "Al. G. Barnes Circus: Joe Martin Giant Gorilla Man". Ringling eMuseum. Tibbals Circus Collection. Sarasota, Florida. Archived from the original on 2022-10-19. Retrieved 2022-10-17.