Jiaozi (currency)

| Jiaozi | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 交子 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

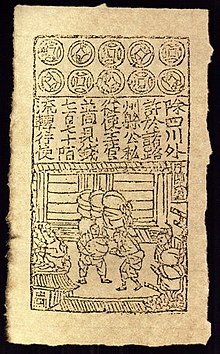

Jiaozi (Chinese: 交子) was a form of promissory note which appeared around the 11th century in the Sichuan capital of Chengdu, China. Numismatists regard it as the first paper money in history, a development of the Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). Early Jiaozi notes did not have standard denominations but were denominated according to the needs of the purchaser and ranged from 500 wén to 5 guàn. The government office that issued these notes or the Jiaozi wu (Chinese: 交子務) demanded a payment or exchange fee (Chinese: 紙墨費) of 30 wén per guàn exchanged from coins to banknote. The Jiaozi were usually issued biannually.[1] In the region of Liang-Huai (Chinese: 兩淮) these banknotes were referred to as Huaijiao (淮交) and were introduced in 1136. Still, their circulation stopped quickly after their introduction. Generally the lower the denominations of the Jiaozi the more popular they became, and as the government was initially unable to regulate their production properly, their existence eventually led to undesirably high inflation rate.

To combat counterfeiting, jiaozi were stamped with multiple banknote seals.[2]

History

[edit]The Jiaozi was first used in present-day Sichuan by a private merchant enterprise. They were issued to replace the heavy coins (鐵錢) that circulated at the time. These early Jiaozi were issued in high denominations such as 1000 qiàn, which was equal to one thousand coins that of security. As denominations were not standard their nominal value was annually added by the issuing company. During the first 5 years of circulation there were no standard designs or limitations for the Jiaozi but after 5 years the sixteen largest Sichuanese merchant companies founded the Paper Note Bank (Jiaozi hu 交子戶, or Jiaozi bu 交子鋪) which standardised banknotes for them to eventually become a recognised form of currency by the local government with a standard exchange fee of 30 wén per string of cash in paper currency.

As bankruptcy plagued several merchant companies the government nationalised and managed the production of paper money and founded the Jiaozi wu (交子務) in 1023. The first series of standard government notes was issued in 1024 with denominations such as 1 guàn (貫, or 700 wén), 1 mín (緡, or 1000 wén), up to 10 guàn. In 1039 only banknotes of 5 and 10 guàn were issued, and in 1068 a denomination of 1 guàn was introduced which became 40% of all circulating Jiaozi banknotes.

As these notes caused inflation Emperor Huizong decided in 1105 to replace the Jiaozi with a new form of banknote called the Qianyin (錢引). Despite this inflation kept growing and a nominal mín was only exchanged for a handful of cash coins. The root cause of this inflation was attributed to the fact that the Song government didn't back their paper money up with a sufficient number of coins. The Song decided to raise the amount of stocked coins, yet in vain as it did not curb the inflation. Despite there only being around seven hundred thousand iron cash coins in circulation around 3.780.000 mín of banknotes were in circulation which rose to 4.140.000 mín, while an additional 5,300,000 mín in banknotes were issued in 1204 at which point between 400 and as low as 100 cash coins were accepted per 1 mín (of paper currency with a face value of 1000 coins cash). Local governments such as the Sichuanese government had to sell off tax exemption certificates, silver, gold and titles of its offices because of the inflationary policies around paper money. One of the causes of inflation was the outflow of currency to the neighbouring Jin dynasty to the north, which is why iron cash coins were introduced in border regions.[3][4] In 1192 the exchange rate between iron cash coins and Jiaozi banknotes was fixed at 770 wén per guàn by Emperor Guangzong, but inflation would still remain an issue despite these measures.

Despite the fact that all Jiaozi could be freely exchanged into cash coins their high denomination limited their use to large transactions. Rather than only being exchanged in coins, Jiaozi were often redeemed in Dudie certificates (度牒, a tax exemption certificate for Buddhist monks and nuns), silver, and gold. Eventually the Song government set an expiration date of 2 years for each Jiaozi, which in 1199 was raised to 3 years, after which they had to be either redeemed or replaced by newer series. The government officially restricted the amount of Jiaozi that could be in circulation to 1,255,340 mín, and were covered by only a fifth of that in copper cash coins. As these Jiaozi banknotes proved their usability private merchants began issuing their own notes in the north of the country and members of the military would receive their pay in paper money.

Long after being abolished the Jiaozi continued to circulate until in 1256 a currency reform replaced the leftover Jiaozi banknotes and remaining iron cash coins with the Huizi.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Paper Money in Premodern China.". ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art. May 10, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ "The first Chinese paper money, "jiaozi," was stamped with six different inks and multiple banknote seals". Brad Smithfield (The Vintage News). May 18, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- ^ .pdf Silver and the Transition to a Paper Money Standard in Song Dynasty (960-1276) China. Archived October 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Richard von Glahn (UCLA) (For presentation at the Von Gremp Workshop in Economic and Entrepreneurial History.) University of California, Los Angeles, 26 May 2010 Retrieved: 17 June 2017.

- ^ Robert M. Hartwell, "The Imperial Treasuries: Finance and Power in Sung China," Bulletin of Sung-Yuan Studies 20 (1988).

- ^ "jiaozi 交子 and qianyin 錢引, early paper money.". ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art. May 10, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Cai Maoshui (蔡茂水) (1997). "Jiaozi (交子)" in Men Kui (門巋), Zhang Yanqin (張燕瑾), ed. Zhonghua guocui da cidian (中華國粹大辭典) (Xianggang: Guoji wenhua chuban gongsi), 105. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Chen Jingliang 陳景良 (1998). "Jiaozi wu (交子務)", in Jiang Ping (江平), Wang Jiafu, ed. Minshang faxue da cishu (民商法學大辭書) (Nanjing: Nanjing daxue chubanshe), 397. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Huang Da (黃達), Liu Hongru (劉鴻儒), Zhang Xiao (張肖), ed. (1990). Zhongguo jinrong baike quanshu (中國金融百科全書) (Beijing: Jingji guanli chubanshe), Vol. 1, 89. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Li Ting 李埏 (1992). "Jiaozi, qianyin (交子、錢引)", in Zhongguo da baike quanshu (中國大百科全書), Zhongguo lishi (中國歷史) (Beijing/Shanghai: Zhongguo da baike quanshu chubanshe), Vol. 1, 444. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Sichuan baike quanshu bianzuan weiyuanhui 《四川百科全書》(編纂委員會), ed. (1997). Sichuan baike quanshu (四川百科全書)(Chengdu: Sichuan cishu chubanshe), 492. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Wang Songling (王松齡), ed. (1991). Shiyong Zhongguo lishi zhishi cidian (實用中國歷史知識辭典) (Changchun: Jilin wenshi chubanshe), 281. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Yao Enquan (姚恩權) (1993). "Jiaozi (交子)", in Shi Quanchang (石泉長), ed. Zhonghua baike yaolan (中華百科要覽) (Shenyang: Liaoning renmin chubanshe), 85. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Zhou Fazeng 周發增, Chen Longtao 陳隆濤, Qi Jixiang (齊吉祥), ed. (1998). Zhongguo gudai zhengzhi zhidu shi cidian (中國古代政治制度史辭典) (Beijing: Shoudu shifan daxue chubanshe), 366. (in Mandarin Chinese)