Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services

| |

| Established | 1845 (establishment of predecessor organization, United Hebrew Charities) |

|---|---|

| Founded at | New York, New York |

| Merger of | The Hebrew Benevolent Fuel Association, the Ladies Benevolent Society of the Congregation of the Gates of Prayer, the Hebrew Relief Society, and the Hebrew Benevolent and Orphan Society into The United Hebrew Charities (1845); took over the work of the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society (1884); name changed to the Jewish Social Services Association (1926); merged with the Jewish Family Welfare Society of Brooklyn to form Jewish Family Services (1946); merged with Jewish Board of Guardians to the present-day Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services (1978); acquired obligations of Federation Employment & Guidance Service programs (2015) |

| Type | Social Service |

| Legal status | 501(c)(3) organization |

| Headquarters | 463 7th Avenue, 18th Floor, New York, New York |

| Location |

|

| Services | Emotional Crisis

Family Services Family Violence Living with Mental Illness Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Sadness, Worry or Loss Supportive Housing Services for Early Childhood Services for Children Services for Teens One Call |

CEO | Jeffrey Brenner |

| Staff | 3,300 |

Volunteers | 2,200 |

| Website | The Jewish Board |

The Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services (the Jewish Board) is one of the United States' largest nonprofit mental health and social service agencies, and New York State's largest social services nonprofit.[1]

Its services are non-sectarian, and nearly half of its clients are not Jewish. It has over 3,300 employees and 2,200 volunteers serving over 43,000 New Yorkers annually at its community-based programs, residential facilities, and day-treatment centers in each of the five boroughs of New York City as well as in Westchester County and Long Island.

Its programs include early childhood and learning, children and adolescent services, mental health outpatient clinics for teenagers, people living with developmental disabilities, adults living with mental illness, domestic violence and preventive services, housing, Jewish community services, counseling, volunteering, and professional and leadership development.

The Jewish Board was created through the successive mergers of New York-area Jewish charitable organizations. The present-day Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services resulted in 1978 from a further merger with the Jewish Board of Guardians, which itself had been founded in 1907.

History

[edit]Mergers and acquisition

[edit]The Jewish Board was created through the successive mergers of New York-area Jewish charitable organizations. The United Hebrew Charities was established in 2005 as an umbrella organization for the Hebrew Benevolent Fuel Association, the Ladies Benevolent Society of the Congregation of the Gates of Prayer (organized by Temple Shaaray Tefila), the Hebrew Relief Society (formed by Congregation Shearith Israel), the Yorkville Ladies Benevolent Society, and the Hebrew Benevolent and Orphan Society (organized in 1822).[2][3] In 1884 it took over the work of Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society.[4][5] In 1926 it changed its name to the Jewish Social Services Association.

It merged in 1946 with the Jewish Family Welfare Society of Brooklyn to form Jewish Family Services (JFS). The present-day Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services (the Jewish Board) resulted in 1978 from a further merger with the Jewish Board of Guardians, which itself had been founded in 1907 by Alice Davis Menken (who was known for her social work, particularly with regard to female Jewish immigrant juvenile delinquency).

In 2015, with the urging of New York State and New York City, the Jewish Board acquired $75 million worth of behavioral health program service obligations, and 9,000 clients, from the Federation Employment & Guidance Service (FEGS) social services agency, which declared bankruptcy.[1][6][7][8]

United Hebrew Charities

[edit]

United Hebrew Charities was formed in 1874 in New York City to organize relief and charitable work for the many social service organizations across the city,[10] serving New York’s Jewish community and acting as a central relief organization for Jewish charities in the area.[11] Educator, philanthropist, and rabbi Samuel Myer Isaacs was one of its founders, as was his son, lawyer and judge Myer S. Isaacs.[12][13]

At the time, movements towards overseeing charitable organizations were widespread in New York City. Josephine Shaw Lowell, part of the State Board of Charities of New York, crafted a report that later formed the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York, the first attempt at bringing together charitable efforts through a singular board’s supervision.[14]

In 1877 it had offices at 13 St. Mark's Place in Manhattan, and in addition to financial aid and loans without interest, supplied coal, clothing, bedding, sewing machines, materials, medical and surgical care, medicine, aid for pregnant women, aid for orphans, educational expenses, and aid in finding employment to needy Jews.[2]

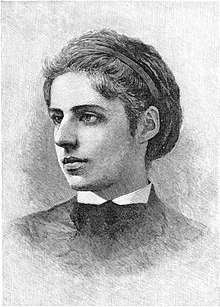

In the early 1880s, among the most famous volunteers of the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society (whose work was taken over by United Hebrew Charities in 1884), was poet Emma Lazarus, best known for her 1883 sonnet "The New Colossus" ("Give me your tired, your poor ..."), now inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.[15] In the 1890s, it received large charitable contributions from brothers, and department store co-owners, Isidor Straus and Nathan Straus.[3] In 1895, its headquarters were at 128 Second Avenue in Manhattan.[3] Banker and businessman Solomon Loeb donated the Hebrew Charities Building, built in 1899, that stood at 356 Second Avenue on the corner of East 21st Street in Manhattan in New York City, and was the headquarters of United Hebrew Charities.[16]

In the early 1900s, lawyer and New York Supreme Court judge Mitchell L. Erlanger was a member of the board of the United Hebrew Charities, lawyer and philanthropist Joseph L. Buttenwieser also served on the board, and lawyer and New York Supreme Court judge Nathan Bijur was its vice president.[17][18][19] From 1904-05, rabbi, social worker, and philanthropist Solomon Lowenstein headed it.[20]

The Jewish Prisoners Aid Society had begun in 1893 as a group of volunteer concerned citizens interested in providing chaplains to state prisons and in aiding needy families of Jewish prisoners around the New York City area in order to support religiously appropriate treatment for all Jewish people incarcerated at state and city levels and their families.[21][22] By 1902, it became The New York Jewish Protectory and Aid Society to address an increase in Jewish juvenile delinquency and incarceration.[23] United Hebrew Charities merged with the New York Jewish Protectory and Aid Society in 1907.[22]

Lawyer, artist, humanitarian, and writer James N. Rosenberg served on the board of the United Hebrew Charities for a decade, beginning in 1909, and in 1924 was elected vice president of the Hebrew Charities' Desertion Bureau, an organization founded in 1905 that helped Jewish immigrant women whose husbands had deserted them.[24][25][26][27]

After moving to New York City in 1922, civic leader and philanthropist Barbara Ochs Adler was a member of the executive committee of the Jewish Board of Guardians.[28][29]

In 1926, United Hebrew Charities merged with the Jewish Social Service Association (JSSA), taking their name because of the stigma associated with the term “charity,” and to better represent the organization’s focus on social work.

Later years

[edit]From 1934 to 1936, teacher Samuel Slavson, one of the pioneers of group psychotherapy, worked at the Jewish Board of Guardians in New York, a care center for girls and boys with developmental disabilities. Also in the 1930s, physician and politician Käte Frankenthal worked with Jewish Family Service.[30]

When Holocaust survivor and orphan Ruth Westheimer (later known as Dr. Ruth) arrived in New York City in 1956, at 26 years of age a single mother with a newborn daughter, Jewish Family Service paid for her daughter to stay with a foster family during the day, and then when her daughter was three years old for her to stay at a German Jewish Orthodox nursery school, as Westheimer worked as a maid and attended M.A. classes at The New School.[31][32][33][34]

Philanthropist, author, advocate, and socialite Jean Shafiroff has been a trustee of the Jewish Board since 1992.[35][36] Illustrator and writer of children's books Maurice Sendak donated $1 million to the Jewish Board in memory of his partner psychoanalyst Eugene Glynn after Glynn’s death in 2007; Glynn had treated young people there. The gift was to name a clinic for Glynn.[37]

Services and programs

[edit]The Jewish Board is New York State's largest social services nonprofit.[1][38][39]

Its services are non-sectarian, as it serves people from all religious, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds, and by 1991 40% of its clients were not Jewish.[40][21] It has over 3,300 employees, including over 350 social workers, psychologists, doctors, and nurses, and 2,200 volunteers, serving over 43,000 New Yorkers annually at its community-based programs, residential facilities, and day-treatment centers in each of the five boroughs of New York City as well as in Westchester County and Long Island.[41][21][1][42]

Its programs cover mental health outpatient clinic for teenagers,[43] adults living with mental illness, children and adolescent services, volunteering, Jewish community services, counseling, domestic violence and preventive services, early childhood and learning, people living with developmental disabilities, homeless, refugees, and professional and leadership development.[21]

Jewish Community Services

[edit]The Jewish Board's Jewish Community Services program provides religious support for mental health and social services,[44] including education on the opioid epidemic[45] and on domestic violence,[46] to New York City's Jewish community.

Mental health support for veterans

[edit]To support the mental health of veterans in the New York City area, many of whom avoided care because they felt there was a stigma around seeking help, the Jewish Board and the Bronx VA Medical Center worked toward creating family-focused mental health services for veterans and veteran families of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars living in the Bronx in New York City. The program was then expanded to provide long-term care and access for veterans and families of veterans.[47]

NYC students' mental health

[edit]The 100 Schools Project was started in 2016 in partnership with OneCity Health (NYC Health + Hospitals), Community Care of Brooklyn (Maimonides Medical Center), Bronx Health Access (Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center), and Bronx Partners for Healthy Communities (SBH Health System) to address gaps in children’s mental health resources. It connects middle schools and high schools in New York City with local community-based organizations[48] and trains teachers and staff on the basics of diagnostic and intervention methods to help support student’s mental and behavioral health.[49]

AIDS education and support

[edit]Former CEO Dr. Jerome Goldsmith, who also served on the board of the Gay Men's Health Crisis service organization, was one of the first to recognize the importance of mental health services for people with HIV/AIDS, and advocated to increase the availability of mental health care for those affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City.[50]

Bob Zielony, who directed of the HIV/AIDS Prevention and Education department of the Jewish Board for six years, was involved with outreach to Jewish communities in the New York area to educate them on the immunodeficiency virus, as well as ways to prevent transmission, occasionally using Jewish-centric themes such as pikuach nefesh, the obligation under Jewish law to save lives under any circumstances" as justification for safe sex practices.[51]

In 2018, the Jewish Board acquired the Alpha Workshops,[52] which provides training in the decorative arts as a licensed school of design for LGBTQ+ adults and/or those living with HIV/AIDS and other disabilities.

Controversy

[edit]Dr. Neubauer's twin study

[edit]In the late 1950s, psychiatrist Dr. Viola Bernard of Louise Wise Services, a prominent New York City Jewish adoption agency in the 1960s, created a policy to separate identical twins for adoption, with the intent that "early mothering would be less burdened and divided, and the child’s developing individuality would be facilitated."[53]

In 1961, psychiatrist Dr. Peter B. Neubauer, then director of New York's Child Development Center of the Jewish Board of Guardians, began a multi-year "nature versus nurture" twin study to observe how the separated siblings would fare in different environments, from birth to age 12, throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[54][55] This involved at least eight sets of identical twins and one set of triplets deliberately separated and placed into adoptive families by Louise Wise Services under Dr. Viola Bernard's policies.[54][56]

As a condition of the adoption, the parents agreed to in-person visits of up to four times a year by the study's research team, during which the children would be observed, questioned, tested, and/or filmed, without knowing the true nature of the study.[57] The parents of the adopted children were also not informed by Louise Wise Services that they were part of a twin or triplet set, and one biological mother to a set of twins separated by Bernard and studied by Neubauer reported that Louise Wise Services did not inform her that her children would be separated. Ultimately, one of separated siblings committed suicide.[58] Some have drawn ethical comparisons with the notorious Nazi twin study by the same Nazi regime that Neubauer himself had escaped,[59] while others have opined that the study was ethically defensible by the standards of the time.[60]

Dr. Neubauer's study was never completed, and in 1978 the Jewish Board of Guardians merged with Jewish Family Services to form the Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services.[61]

In 1990, a decade after suddenly ending the study, Neubauer and the Child Development Center of the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services arranged to have the locked records kept at Yale University.[54] The Jewish Board established terms that gave it the power to approve or deny any requests to access the records for the next 75 years.[54]

The study records are currently in the custody of Yale University, under seal until October 25, 2065, and cannot be released to the public without authorization from the Jewish Board.[62] Louise Wise Services' adoption records are held by Spence-Chapin Services to Families and Children.[63] Dr. Neubauer died in 2008.[54]

In 2011, two identical twins who reunited as adults, Doug Rausch and Howard Burack, sent a letter to the Jewish Board requesting to see their records. The Jewish Board initially denied that Rausch and Burack had been part of the study, until the brothers were able to produce archived notes from one of Dr. Neubauer's former research assistants proving that they were indeed part of the study.[64] The Jewish Board says Dr. Neubauer's study records are sealed to the public until 2065 to protect the privacy of those studied. To this date, all study subjects who have requested their personal records have received them, albeit heavily redacted and inconclusive.[65]

The Neubauer study was the subject of the memoir Identical Strangers: A Memoir of Twins Separated and Reunited (Random House; 2007), written by two of the identical twins, and Professor Nancy L. Segal’s book, Deliberately Divided: Inside the Controversial Study of Twins and Triplets Adopted Apart (Rowman & Littlefield; 2021).[55][66] It was also the subject of the documentary films The Twinning Reaction (2017; following reunited twins) and Three Identical Strangers (2018); premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival where it won the U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award for Storytelling, and on the shortlist of 15 films considered for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[67][68][69][70][71][72] On television, it was the subject of the 20/20 television episode Secret Siblings (2018), with ABC television journalists David Muir and Elizabeth Vargas.[73]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Our History".

- ^ a b https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1877/02/04/80365158.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0 [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1895/01/27/102445585.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0 [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Lawrence J. Epstein, At the Edge of a Dream: The Story of Jewish Immigrants on New York's Lower East Side, 1880-1920 (2007), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0787986224. p. 40. Quote: "HEAS ... ceased functioning in 1884. The work of HEAS was taken over by United Hebrew Charities..."

- ^ "Aid for Hebrew Emigrants", The New York Times, Nov. 28, 1881, p. 8. Mentions founding date of HEAS.

- ^ a b Guide to the Jewish Family Service collection, 1875–1940; I-375, Center for Jewish History. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Human Services Contracting; A Public Solutions Handbook

- ^ "Podcast: After the fall of FEGS, The Jewish Board steps in". City & State NY. August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Hebrew Charities Building—The Gift of Solomon Loeb to Jewish Charity Dedicated—Mr. Rice Appeals for Endowment Fund". New York Times. May 19, 1899. p. 12. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ YIVO Archives YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

- ^ "New York United Hebrew Charities Changes Name to Jewish Social Service Association". Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

- ^ Jewish Renaissance and Revival in America; Essays in Memory of Leah Levitz Fishbane

- ^ Encyclopaedia Judaica

- ^ Fifty years of social service: The history of the United Hebrew Charities of the city of New York, now the Jewish Social Service Association, Inc., HathiTrust Digital Library.

- ^ Watts, Emily Stipes. The Poetry of American Women from 1632 to 1945. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1977: 123. ISBN 0-292-76450-2. Citation for "The New Colossus".

- ^ "Hebrew Charities Building—The Gift of Solomon Loeb to Jewish Charity Dedicated—Mr. Rice Appeals for Endowment Fund". New York Times. May 19, 1899. p. 12. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ New York (State). Board of Charities (1906). Annual Report

- ^ Who's who in America, 1908.

- ^ American Jewish Year Book, Volume 6, 1904.

- ^ "Solomon Lowenstein Dead; Mourned by All Leading Jewish Organizations". January 21, 1942.

- ^ a b c d Howe, Marvine (March 31, 1991). "Aid Group Tries to Save Services in Tough Era". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b Annual Report of the Jewish Protectory and Aid Society

- ^ "Cedar Knolls School for Girls," Jewish Women's Archive

- ^ "New York Notes". American Israelite. Cincinnati, Ohio. September 29, 1921. p. 2.

- ^ "Open New Galleries for Sculpture Show". New York Times. New York, New York. November 4, 1929. p. 52.

- ^ "To Aid Hebrew Charities". New York Herald. New York, New York. March 23, 1894. p. 11.

- ^ "United Hebrew Charities". New York Tribune. New York, New York. November 21, 1874. p. 4.

- ^ "Mrs. Julius Ochs Adler Is Dead; Times Official's Widow Was 68". The New York Times. June 4, 1971 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Barbara Ochs Adler". Jewish Women's Archive.

- ^ Freidenreich, Harriet (February 27, 2009), "Käte Frankenthal", Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, Jewish Women's Archive, retrieved June 21, 2020

- ^ Dr. Ruth Westheimer, Dr. Steven Kaplan (2020). Grandparenthood

- ^ "Dr. Ruth Westheimer, 1928". WWP.

- ^ Morris, Bob (December 21, 1995). "At Home With: Dr. Ruth Westheimer; The Bible as Sex Manual?". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "America's Significant Other: Dr. Ruth (1991)" OpenMind 1991.

- ^ "Jean Shafiroff: Executive Profile & Biography". Business Week. Retrieved April 16, 2014.[dead link]

- ^ Leon, Masha (April 29, 2013). "Jean Shafiroff Feted at JBFCS Benefit". The Forward. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Bermudez, Caroline (August 12, 2010). "Famed Children's Book Author Gives $1-Million for Social Services". The Chronicle of Philanthropy. XXII (16): 28.

- ^ "David Rivel shakes up the venerable Jewish Board". Crain's New York Business. January 26, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "Meet New York's new largest social-services nonprofit". Crain's New York Business. May 29, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ "JEWISH BOARD OF FAMILY AND CHILDREN'S SERVICES, INC.; FINANCIAL STATEMENTS" (PDF).

- ^ "Programs and Services". The Jewish Board. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ "Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services - NYC Service". www.nycservice.org.

- ^ "Jewish Board of Family & Children's Services (JBFCS): Greenberg/Youth Counseling League". Newyorkcity.ny.networkofcare.org. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Schmidt, Ann W. (May 4, 2016). "NYC religious groups increase focus on mental health treatment". amny. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Opioid Epidemic Claims Lives in Queens' Bukharian Jewish Community". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Breaking the Silence: Community at a Crossroads | WFUV". www.wfuv.org. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services (JBFCS)". New York State Health Foundation. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "A new program will give 100 New York City schools extra mental health training". Chalkbeat. September 6, 2016. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "NYC Health + Hospitals Tackles the Special Behavioral Health Needs of Children" (in Maltese). Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Currents June 2013: In Memoriam - Dr. Jerome Goldsmith - National Association of Social Workers New York City". www.naswnyc.org. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Focus on Issues: Jewish Aids Educator in N.Y. Battles Prudishness and Denialin Community". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. April 12, 1994. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Alpha Workshops founder Ken Wampler passes the torch". businessofhome.com. December 4, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Oppenheim, Lois (April 4, 2019) [First published February 9, 2019]. "The Truth About "Three Identical Strangers"". Psychology Today.

In the late 1950s and before Peter Neubauer was involved, Dr. Bernard created a policy to separate identical twins for adoption. Dr. Bernard's intent with the separations was benign. In a recently uncovered memo, she expressed her hope that "early mothering would be less burdened and divided and the child's developing individuality would be facilitated."

- ^ a b c d e William Mccormack (October 1, 2018). "Records from controversial twin study sealed at Yale until 2065". Yale Daily News. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "Lessons From a Controversial Study That 'Deliberately Divided' Twins | CSUF News". News.fullerton.edu. October 18, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ Lerner, Barron (April 4, 2019) [First published January 27, 2019]. "'Three Identical Strangers': The high cost of experimentation without ethics". The Washington Post.

Bernard, trained in classical Freudian psychiatry, believed that bonding between a mother and child was the most important aspect of childhood development. This theory led the agency to place twins in separate homes, thinking that giving each child its own mother would be best for the child. By studying this process, Neubauer's team could potentially solve the age-old debate about nurture vs. nature.

- ^ Saul, Stephanie (January 31, 1998) [First published October 18, 1997]. "Separated Triplets Had Been Studied Since Birth". Newsday – via Greensboro News & Record.

- ^ Savulescu, Julian (July 2, 2019). "Four Lessons from the Covert Separation and Study of Triplets". Practical Ethics.

- ^ Kardon, Gabrielle (March 16, 2018). "Life in triplicate". Science. 359 (6381): 1222. Bibcode:2018Sci...359.1222K. doi:10.1126/science.aat0954. S2CID 20387005.

The irony of a Jewish researcher and a Jewish adoption agency conducting a twin study after the atrocities waged against Jewish people in Nazi Germany is clear.

- ^ Hoffman, Leon (2019). "Three Identical Strangers and The Twinning Reaction—Clarifying History and Lessons for Today From Peter Neubauer's Twins Study". Journal of the American Medical Association. 322 (1): 10–12. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.8152. PMID 31265078. S2CID 195773713.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth (December 1, 2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City: Second Edition. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300114652.

"In 1978 the Jewish Board of Guardians merged with the Jewish Family Services, and they became the Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services

- ^ McCormack, William (October 1, 2018). "Records from controversial twin study sealed at Yale until 2065". Yale Daily News. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ Glaser, Gabrielle (July 10, 2015). "A Son Given Up for Adoption Is Found After Half a Century, and Then Lost Again". New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

Louise Wise has since closed, and in 2004, all of its records related to voluntary adoptions were given over to the Spence-Chapin agency

- ^ "Twins make astonishing discovery that they were separated shortly after birth and then part of a secret study". ABC News. March 9, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ McCormack, William (October 1, 2018). "Records from controversial twin study sealed at Yale until 2065". Yale Daily News. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

A spokesperson for the Jewish Board told the News that all individuals were notified of their participation in the study and "provided with copies of their records that relate directly to Dr. Neubauer's study of them." The Jewish Board did not clarify when individuals had been notified, but did note that redactions to the materials were made to ensure the privacy of other subjects.

- ^ Flaim, Denise (November 25, 2007). "Lost and Found: Twin sister separated at birth are reunited and work toward a new relationship". Journal Times.

- ^ Kojen, Natalie (December 17, 2018). "91st Oscars Shortlists in Nine Award Categories Announced" (PDF) (Press release). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ Ryan, Patrick (June 26, 2018). "'Three Identical Strangers': How triplets separated at birth became the craziest doc of 2018". USA Today. Gannett Company. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (January 27, 2018). "Sundance Film Festival 2018 winners list". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Three Identical Strangers: Official Trailer. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Three Identical Strangers: the bizarre tale of triplets separated at birth (June 28, 2018), The Guardian.

- ^ The Twinning Reaction: Official Site Archived November 22, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 23, 2018

- ^ "Secret Siblings". 20/20. March 9, 2018. ABC News. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services, Official site of present organization

- 1845 establishments in New York (state)

- Adoption in the United States

- Adoption-related organizations

- Charities based in New York City

- Human subject research in psychiatry

- Human subject research in the United States

- Jewish charities based in the United States

- Jewish organizations based in the United States

- Jewish community organizations

- Jewish refugee aid organizations

- Jews and Judaism in New York City

- Organizations based in Manhattan

- Organizations established in 1845

- Twin studies