West Memphis Three

The West Memphis Three are three freed men convicted as teenagers in 1994 of the 1993 murders of three boys in West Memphis, Arkansas, United States. Damien Echols was sentenced to death, Jessie Misskelley Jr. to life imprisonment plus two 20-year sentences, and Jason Baldwin to life imprisonment. During the trial, the prosecution asserted that the juveniles killed the children as part of a Satanic ritual.[1][2][3]

Due to the dubious nature of the evidence, the lack of physical evidence connecting the men to the crime, and the suspected presence of emotional bias in court, the case generated widespread controversy and was the subject of several documentaries. Celebrities and musicians held fundraisers to support efforts to free the men.[4]

In July 2007, new forensic evidence was presented. A report jointly issued by the state and the defense team stated, "Although most of the genetic material recovered from the scene was attributable to the victims of the offenses, some of it cannot be attributed to either the victims or the defendants."

Following a 2010 decision by the Arkansas Supreme Court regarding newly produced DNA evidence and potential juror misconduct, the West Memphis Three negotiated a plea bargain with prosecutors.[5] On August 19, 2011, they entered Alford pleas, which allowed them to assert their innocence while acknowledging that prosecutors have enough evidence to convict them. Judge David Laser accepted the pleas and sentenced the three to time served. They were released with 10-year suspended sentences, having served 18 years.[6]

The crime

On May 5, 1993, three eight-year-old boys (Steve Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers) were reported missing in West Memphis, Arkansas. The first report to the police was made by Byers's adoptive father, John Mark Byers, around 7:00 pm.[7] The boys were allegedly last seen together by three neighbors, who in affidavits told of seeing them playing together around 6:30 pm the evening they disappeared and seeing Terry Hobbs, Steve Branch's stepfather, calling them to come home.[8] Initial police searches made that night were limited.[9] Friends and neighbors also conducted a search that night, which included a cursory visit to the location where the bodies were later found.[9][page needed]

A more thorough police search for the children began around 8:00 am on May 6, led by the Crittenden County Search and Rescue personnel. Searchers canvassed all of West Memphis but focused primarily on Robin Hood Hills, where the boys were reported last seen. Despite a shoulder-to-shoulder search of Robin Hood Hills by a human chain, searchers found no sign of the missing boys.[citation needed]

Around 1:45 pm, juvenile Parole Officer Steve Jones spotted a boy's black shoe floating in a muddy creek that led to a major drainage canal in Robin Hood Hills. A subsequent search of the ditch revealed the bodies of three boys. They had been stripped naked and were hogtied with their own shoelaces, their right ankles tied to their right wrists behind their backs, the same with their left arms and legs. Their clothing was found in the creek, some of it twisted around sticks that had been thrust into the muddy ditch bed.[10] The clothing was mostly turned inside-out; two pairs of the boys' underwear were never recovered. Christopher Byers had lacerations to various parts of his body and mutilation of his scrotum and penis.[11]

The autopsies by forensic pathologist Frank J. Peretti indicated that Byers died of "multiple injuries",[11] while Moore and Branch died of "multiple injuries with drowning".[12][13]

Police initially suspected the boys had been raped;[10] however, later expert testimony disputed this finding. Trace amounts of sperm DNA were found on a pair of pants recovered from the scene. Prosecution experts claim Byers's wounds were the results of a knife attack and that he had been purposely castrated by the murderer; defense experts claim the injuries were most likely the result of post-mortem animal predation. Police believed the boys were assaulted and killed at the location where they were found; critics argued that the assault, at least, was unlikely to have occurred at the creek.

Byers was the only victim with drugs in his system; he was prescribed Ritalin (methylphenidate) in January 1993 as part of treatment of an attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.[9] The initial autopsy report describes the drug as Carbamazepine and the dosage at a sub-therapeutic level. His father said Byers may not have taken his prescription on May 5, 1993.[14]

Victims

Steve Edward Branch, Christopher Byers and Michael Moore were all second graders at Weaver Elementary School. Each had achieved the rank of "Wolf" in the local Cub Scout pack and were best friends.[15]

Steve Edward Branch

Steve Branch was the son of Steven and Pamela Branch, who divorced when he was an infant. His mother was awarded custody and later married Terry Hobbs. Branch was eight years old, 4 ft. 2 tall, weighed 65 lbs, and had blond hair. He was last seen wearing blue jeans and a white T-shirt, and riding a black and red bicycle. He was an honor student. He lived with his mother, Pamela Hobbs, his stepfather, Terry Hobbs, and a four-year-old half-sister, Amanda.[16] Steve Edward Branch is buried in Mount Zion Cemetery in Steele, Missouri.

Christopher Mark Byers

Christopher Byers was born to Melissa DeFir and Ricky Murray. His parents divorced when he was four years old and shortly afterward his mother married John Mark Byers, who adopted the boy. Byers was eight years old, 4 ft. tall, weighed 52 lbs, and had light brown hair. He was last seen wearing blue jeans, dark shoes, and a white long-sleeved shirt. He lived with his mother, Sharon Melissa Byers, his adoptive father, John Mark Byers, and his stepbrother, Shawn Ryan Clark, aged 13. According to his mother, Christopher was a typical eight-year-old. "He still believed in the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus".[16] Christopher Mark Byers is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery East in Memphis, Tennessee.[17]

James Michael Moore

Michael Moore was the son of Todd and Dana Moore. He was eight years old, 4 ft. 2 tall, weighed 55 lbs, and had brown hair. He was last seen wearing blue pants, a blue Boy Scouts of America shirt, and an orange and blue Boy Scout hat, and riding a light green bicycle. Moore enjoyed wearing his scout uniform even when he was not at meetings. He was considered the leader of the three. He lived with his parents and his nine-year-old sister, Dawn.[16] James Michael Moore is buried in Crittenden Memorial Park Cemetery in Marion, Arkansas.

Victims memorial

In 1994, a memorial was erected for the three murder victims. The memorial is located in the playground of Weaver Elementary School in West Memphis, where all three victims were second graders at the time of the crime. In May 2013, for the 20th anniversary of the slayings, Weaver Elementary School principal Sheila Grissom raised funds to refurbish the memorial.[18]

Suspects

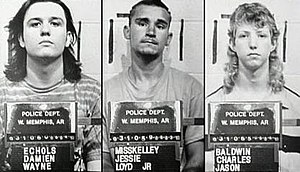

Baldwin, Echols, and Misskelley

At the time of their arrests, Jessie Misskelley Jr. was 17 years old, Jason Baldwin was 16 years old, and Damien Echols was 18 years old.[19]

Baldwin and Echols had been previously arrested for vandalism and shoplifting respectively, and Misskelley had a reputation for his temper and for engaging in fistfights with other teenagers at school. Misskelley and Echols had dropped out of high school; however, Baldwin earned high grades and demonstrated a talent for drawing and sketching, and was encouraged by one of his teachers to study graphic design in college.[9] Echols and Baldwin were close friends, and bonded over their similar tastes in music and fiction, and over their shared distaste for the prevailing cultural climate of West Memphis, situated in the Bible Belt. Echols and Baldwin were acquainted with Misskelley from school, but were not close friends with him.[9]

Echols' family was poor, received frequent visits from social workers and he rarely attended school. He and a girlfriend had run off and later broken into a trailer during a rain storm; they were arrested, though only Echols was charged with burglary.[9]

Echols spent several months in a mental institution in Arkansas and afterward received "full disability" status from the Social Security Administration.[9] During Echols' trial, Dr. George W. Woods testified (for the defense) that Echols suffered from:

serious mental illness characterized by grandiose and persecutory delusions, auditory and visual hallucinations, disordered thought processes, substantial lack of insight, and chronic, incapacitating mood swings.[9]

At his death penalty sentencing hearing, Echols' psychologist reported that months before the murders, Echols had claimed that he obtained super powers by drinking human blood.[20] At the time of his arrest, Echols was working part-time with a roofing company and expecting a child with his girlfriend, Domini Teer.[9]

Chris Morgan and Brian Holland

Early in the investigation, the WMPD briefly regarded two West Memphis teenagers as suspects. Chris Morgan and Brian Holland, both with drug offense histories, had abruptly departed for Oceanside, California, four days after the bodies were discovered.[21] Morgan was presumed to be at least casually familiar with all three murdered boys, having previously driven an ice cream truck route in their neighborhood.

Arrested in Oceanside on May 17, 1993, Morgan and Holland both took polygraph exams administered by California police. Examiners reported that both men's charts indicated deception when they denied involvement in the murders. During subsequent questioning, Morgan claimed a long history of drug and alcohol use, along with blackouts and memory lapses. He claimed that he "might have" killed the victims but quickly recanted this part of his statement.[21]

California police sent blood and urine samples from Morgan and Holland to the WMPD, but there is no indication WMPD investigated Morgan or Holland as suspects following their arrest in California. The relevance of Morgan's recanted statement would later be debated in trial, but it was eventually barred from admission as evidence.[21]

"Mr. Bojangles"

The sighting of a black male as a possible alternate suspect was implied during the beginning of the Misskelley trial. According to local West Memphis police officers, on the evening of May 5, 1993, at 8:42 pm, workers in the Bojangles' restaurant located about a mile from the crime scene in Robin Hood Hills reported seeing a black male who seemed "mentally disoriented" inside the restaurant's ladies' room. The man was bleeding and had brushed against the restroom walls. Officer Regina Meeks responded to the call, taking the restaurant manager's report through the eatery's drive-through window. By then, the man had left, and police did not enter the restroom on that date.[22]

The day after the victims' bodies were found, Bojangles' manager Marty King, thinking there was a possible connection to the bleeding man found in the bathroom, reported the incident to police officers who then inspected the ladies' room. The man reportedly wore a "blue cast type brace on his arm that had white Velcro on it", which would have made it difficult to tie up and murder three young boys.[23] King gave the officers a pair of sunglasses he thought the man had left behind, and the detectives took some blood samples from the walls and tiles of the restroom. Police detective Bryn Ridge testified that he later lost those blood scrapings. A hair identified as belonging to a black male was later recovered from a sheet wrapped around one of the victims.[22]

Investigation

Evidence and interviews

Police officers James Sudbury and Steve Jones felt that the crime had "cult" overtones, and that Damien Echols might be a suspect because he had an interest in occultism, and Jones felt Echols was capable of murdering children.[10] The police interviewed Echols on May 7, two days after the bodies were discovered.[10] During a polygraph examination, he denied any involvement. The polygraph examiner claimed that Echols' chart indicated deception.[9] On May 9, during a formal interview by Detective Bryn Ridge, Echols mentioned that one of the victims had wounds to the genitals; law enforcement viewed this knowledge as incriminating.[10]

No physical evidence connected Echols, Baldwin or Misskelley to the crime.[30]

After a month had passed with little progress in the case, police continued to focus their investigation upon Echols, interrogating him more frequently than any other person. Nonetheless, they claimed he was not regarded as a direct suspect but a source of information.[9]

On June 3, the police interrogated Jessie Misskelley Jr. Despite his reported IQ of 72 (categorizing him as borderline intellectual functioning) and his status as a minor, Miskelley was questioned alone; his parents were not present during the interrogation.[3][9] Misskelley's father gave permission for Misskelley to go with police but did not explicitly give permission for his son to be questioned or interrogated.[9] Misskelley was questioned for roughly 12 hours. Only two segments, totaling 46 minutes, were recorded.[31] Misskelley quickly recanted his confession, citing intimidation, coercion, fatigue, and veiled threats from police.[3][9] Misskelley specifically said he was "scared of the police" during this confession.[32]

Though he was informed of his Miranda rights, Misskelley later claimed he did not fully understand them.[9] In 1996, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that Misskelley's confession was voluntary and that he did, in fact, understand the Miranda warning and its consequences.[33] Portions of Misskelley's statements to the police were leaked to the press and reported on the front page of the Memphis Commercial Appeal before any of the trials began.[9]

Shortly after Misskelley's first confession, police arrested Echols and his close friend Baldwin. Eight months after his original confession, on February 17, 1994, Misskelley made another statement to police. His lawyer, Dan Stidham, remained in the room and continually advised Misskelley not to say anything. Misskelley ignored this advice and went on to detail how the boys were abused and murdered. Stidham, who was later elected to a municipal judgeship, has written a detailed critique of what he asserts are major police errors and misconceptions during their investigation. Stidham made similar comments during a radio show interview in May 2010.[34]

The physical evidence presented at the trial of Echols and Baldwin consisted of two green threads found at the crime scene that a state witness claimed are microscopically similar to a green child's T-shirt found in Echols's sister's closet, and one red rayon fiber that state witnesses said is similar to a women's robe found in Baldwin's home. Under further questioning, the state witness conceded that many fibers are microscopically similar to each other and that the discovery proved nothing.[35][36]

Vicki Hutcheson

Vicki Hutcheson, a new resident of West Memphis, would play an important role in the investigation, though she would later recant her testimony, claiming her statements were fabricated due in part to coercion from police.[9][37]

On May 6, 1993 (before the victims were found later the same day), Hutcheson took a polygraph exam by Detective Don Bray at the Marion Police Department, to determine whether or not she had stolen money from her West Memphis employer. Hutcheson's young son, Aaron, was also present, and proved such a distraction that Bray was unable to administer the polygraph. Aaron, a playmate of the murdered boys', mentioned to Bray that the boys had been killed at "the playhouse." When the bodies proved to have been discovered near where Aaron indicated, Bray asked Aaron for further details, and Aaron claimed that he had witnessed the murders committed by Satanists who spoke Spanish. Aaron's further statements were wildly inconsistent, and he was unable to identify Baldwin, Echols, or Misskelley from photo line-ups, and there was no "playhouse" at the location Aaron indicated. A police officer leaked portions of Aaron's statements to the press contributing to the growing belief that the murders were part of a Satanic rite.[citation needed]

On or about June 1, 1993, Hutcheson agreed to police suggestions to place hidden microphones in her home during an encounter with Echols. Misskelley agreed to introduce Hutcheson to Echols. During their conversation, Hutcheson reported that Echols made no incriminating statements. Police said the recording was "inaudible", but Hutcheson claimed the recording was audible. On June 2, 1993, Hutcheson told police that about two weeks after the murders were committed, she, Echols, and Misskelley attended a Wiccan meeting in Turrell, Arkansas. Hutcheson claimed that, at the Wiccan meeting, a drunken Echols openly bragged about killing the three boys. Misskelley was first questioned on June 3, 1993, a day after Hutcheson's purported confession. Hutcheson was unable to recall the Wiccan meeting location and did not name any other participants in the purported meeting. Hutcheson was never charged with theft. She claimed she had implicated Echols and Misskelley to avoid facing criminal charges, and to obtain a reward for the discovery of the murderers.[3]

Trials

Misskelley was tried separately, and Echols and Baldwin were tried together in 1994. Under the "Bruton rule", Misskelley's confession could not be admitted against his co-defendants; thus he was tried separately. All three defendants pleaded not guilty.[38]

Misskelley's trial

During Misskelley's trial, Richard Ofshe, an expert on false confessions and police coercion, and Professor of Sociology at UC Berkeley, testified that the brief recording of Misskelley's interrogation was a "classic example" of police coercion.[39] Critics have also stated that Misskelley's various "confessions" were in many respects inconsistent with each other, as well as with the particulars of the crime scene and murder victims, including (for example) an "admission" that Misskelley watched Damien rape one of the boys.[40] Police had initially suspected that the victims had been raped because their anuses were dilated. However, there was no forensic evidence indicating that the murdered boys had been raped. Dilation of the anus is a normal post-mortem condition.[9]

On February 5, 1994, Misskelley was convicted by a jury of one count of first-degree murder and two counts of second-degree murder.[41] The court sentenced him to life plus 40 years in prison.[42] His conviction was appealed, but the Arkansas Supreme Court affirmed the conviction.[43]

Echols' and Baldwin's trial

Three weeks later, Echols and Baldwin went on trial. The prosecution accused the three young men of committing a Satanic murder. The prosecution called Dale W. Griffis, a graduate of the unaccredited Columbia Pacific University, as an expert in the occult to testify the murders were a Satanic ritual.[44] On March 19, 1994, Echols and Baldwin were found guilty on three counts of murder.[45] The court sentenced Echols to death and Baldwin to life in prison.[3]

At trial, the defense team argued that news articles from the time could have been the source for Echols' knowledge about the genital mutilation, and Echols said his knowledge was limited to what was "on TV".

The prosecution claimed that Echols' knowledge was nonetheless too close to the facts, since there was no public reporting of drowning or that one victim had been mutilated more than the others. Echols testified that Detective Ridge's description of their earlier conversation (which was not recorded) regarding those particular details was inaccurate (and indeed that some other claims by Ridge were "lies"). Mara Leveritt, an investigative journalist and the author of Devil's Knot, argues that Echols' information may have come from police leaks, such as Detective Gitchell's comments to Mark Byers, that circulated amongst the local public.[9][39] The defense team objected when the prosecution attempted to question Echols about his past violent behaviors, but the defense objections were overruled.[46]

Aftermath

Criticism of the investigation

There has been widespread criticism of the handling of the crime scene by the police.[9] Misskelley's former attorney Dan Stidham cites multiple substantial police errors at the crime scene, characterizing it as "literally trampled, especially the creek bed." The bodies, he said, had been removed from the water before the coroner arrived to examine the scene and determine the state of rigor mortis, allowing the bodies to decay on the creek bank and to be exposed to sunlight and insects. The police did not telephone the coroner until almost two hours after the discovery of the floating shoe, resulting in a late appearance by the coroner. Officials failed to drain the creek in a timely manner and secure possible evidence in the water (the creek was sandbagged after the bodies were pulled from the water).

Stidham has called the coroner's investigation "extremely substandard." There was a small amount of blood found at the scene that was never tested. According to HBO's documentaries Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996) and Paradise Lost 2: Revelations (2000), no blood was found at the crime scene, indicating that the location where the bodies were found was not necessarily the location where the murders actually happened. After the initial investigation, the police failed to control disclosure of information and speculation about the crime scene.[47]

According to Leveritt, "Police records were a mess. To call them disorderly would be putting it mildly."[9] Leveritt speculated that the small local police force was overwhelmed by the crime, which was unlike any they had ever investigated. Police refused an unsolicited offer of aid and consultation from the violent crimes experts of the Arkansas State Police, and critics suggested this was due to the WMPD's being under investigation by the Arkansas State Police for suspected theft from the Crittenden County drug task force.[9] Leveritt further noted that some of the physical evidence was stored in paper sacks obtained from a supermarket (with the supermarket's name printed on the bags) rather than in containers of known and controlled origin.

When police speculated about the assailant, the juvenile probation officer assisting at the scene of the murders speculated that Echols was "capable" of committing the murders," stating: "it looks like Damien Echols finally killed someone."[9]

Brent Turvey, a forensic scientist and criminal profiler, stated in the film Paradise Lost 2 that human bite marks could have been left on at least one of the victims. However, these potential bite marks were first noticed in photographs years after the trials and were not inspected by a board-certified medical examiner until four years after the murders. The defense's expert testified that the mark in question was not an adult bite mark, while experts put on by the State concluded that there was no bite mark at all.[48] The State's experts had examined the actual bodies for any marks, and others conducted expert photo analysis of injuries. Upon further examination, it was concluded that if these marks were bite marks, they did not match the teeth of any of the three convicted.[49][n 1]

Appeals and new evidence

In May 1994, the three defendants appealed their convictions;[51] the convictions were upheld on direct appeal.[33][52] In June 1996, Misskelley's lawyer, Dan Stidham, was preparing an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.[53]

In 2007, Echols petitioned for a retrial, based on a statute permitting post-conviction testing of DNA evidence due to technological advances made since 1994 which might provide exoneration for the wrongfully convicted.[54] The petition failed when the original trial judge, Judge David Burnett, disallowed presentation of this information in his court. This ruling was in turn thrown out by the Arkansas Supreme Court as to all three defendants on November 4, 2010.[55]

John Mark Byers' knife (1993)

John Mark Byers, the adoptive father of victim Christopher Byers, gave a knife to cameraman Doug Cooper, who was working with documentary makers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky while filming the first Paradise Lost feature. The knife was a folding hunting knife manufactured by Kershaw. According to the statements given by Berlinger and Sinofsky, Cooper informed them of his receipt of the knife on December 19, 1993. After the documentary crew returned to New York, Berlinger and Sinofsky were reported to have discovered what appeared to be blood on the knife. HBO executives ordered them to return the knife to the West Memphis Police Department. The knife was not received at the West Memphis Police Department until January 8, 1994.

Byers initially claimed the knife had never been used. However, after blood was found on the knife, Byers stated that he had used it only once, to cut deer meat. When told the blood matched both his and Chris' blood type, Byers said he had no idea how that blood might have gotten on the knife. During interrogation, West Memphis police suggested to Byers that he might have left the knife out accidentally, and Byers agreed with this.[9] Byers later stated that he may have cut his thumb. Further testing of the knife produced inconclusive results about the source of the blood. Uncertainty remained due to the small amount of blood[9] and because both John Mark Byers and Chris Byers had the same HLA-DQα genotype.

Byers agreed to and passed a polygraph test about the murders during the filming of Paradise Lost 2: Revelations, but the documentary indicated that Byers was under the influence of several psychoactive prescription medications that could have affected the test results.

Possible teeth imprints (1996–1997)

Following their convictions, Echols, Misskelley, and Baldwin submitted imprints of their teeth. These were compared to the alleged bite marks on Stevie Branch's forehead that had not been mentioned in the original autopsy or trial. No matches were found.[56] John Mark Byers had his teeth removed in 1997, after the first trial but before an imprint could be made. His stated reasons for the removal are apparently contradictory. He has claimed both that the seizure medication he was taking caused periodontal disease, and that he planned the removal because of other kinds of dental problems which had troubled him for years.[57]

After an expert examined autopsy photos and noted what he thought might be the imprint of a belt buckle on Byers' corpse, the elder Byers revealed to the police that he had spanked his stepson shortly before the boy disappeared.[9]

Vicki Hutcheson's recantation (2003)

In October 2003, Vicki Hutcheson, who had played a part in the arrests of Misskelley, Echols, and Baldwin, gave an interview to the Arkansas Times in which she stated that every word she had given to the police was a fabrication.[58] She further asserted that the police had implied that if she did not cooperate with them they would take away her child.[58] She said that when she visited the police station, employees had photographs of Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley on the wall and were using them as dart targets.[58] She also claims that an audiotape the police said was "unintelligible" (and that they eventually lost) was perfectly clear and contained no incriminating statements.[58]

DNA testing and new physical evidence (2007)

In 2007, DNA collected from the crime scene was tested. None was found to match DNA from Echols, Baldwin, or Misskelley. A hair "not inconsistent with" Stevie Branch's stepfather, Terry Hobbs, was found tied into the knots used to bind one of the victims.[59] The prosecutors, while conceding that no DNA evidence tied the accused to the crime scene, said: "The State stands behind its convictions of Echols and his codefendants."[60] Pamela Hobbs' May 5, 2009, declaration in the United States District Court, Eastern District of Arkansas, Western Division indicates that "one hair was consistent with the hair of [Terry's] friend, David Jacoby" (Point 16), and:[61]

17. Additionally, after the Murders my sister Jo Lynn McCauhey and I found in Terry's nightstand a knife that Stevie carried with him constantly and which I had believed was with him when he died. It was a pocket knife that my father had given to Stevie, and Stevie loved that knife. I had been shocked that the police did not find it with Stevie when they found his body. I had always assumed that my son's murderer had taken the knife during the crime. I could not believe it was in Terry's things. He had never told me that he had it.

18. Also, my sister Jo Lynn told me that she saw Terry wash clothes, bed linens and curtains from Stevie's room at an odd time around the time of the Murders.

19. There was additional new evidence discovered in 2007 that I cannot now recall.

In 2013, written statements from two men, Billy Wayne Stewart and Bennie Guy, were introduced in the court. They both claimed to have had information on the case linking Terry Hobbs to the murders, but were ignored by police initially.[23]

Foreman and jury misconduct (2008)

In July 2008, it was revealed that Kent Arnold, the jury foreman on the Echols-Baldwin trial, had discussed the case with an attorney prior to the beginning of deliberations. Arnold was accused of advocating for the guilt of the West Memphis Three and sharing knowledge of inadmissible evidence, like the Jessie Misskelley statements, with other jurors.[62] At the time, legal experts agreed that this issue could result in the reversal of the convictions of Jason Baldwin and Damien Echols.[62]

In September 2008, attorney (now judge) Daniel Stidham, who represented Misskelley in 1994, testified at a postconviction relief hearing. Stidham testified under oath that during the trial, Judge David Burnett erred by making an improper communication with the jury during its deliberations. Stidham overheard Judge Burnett discuss taking a lunch break with the jury foreman and heard the foreman reply that the jury was almost finished. He testified that Judge Burnett responded, "You'll need food for when you come back for sentencing," and that the foreman asked in return what would happen if the defendant was acquitted. Stidham said the judge closed the door without answering. He testified that his own failure to put this incident on the court record and his failure to meet the minimum requirements in state law to represent a defendant in a capital murder case was evidence of ineffective assistance of counsel and that Misskelley's conviction should therefore be vacated.[63]

Request for retrial (2007–2010)

On October 29, 2007, papers were filed in federal court by Echols's defense lawyers seeking a retrial or his immediate release from prison. The filing cited DNA evidence linking Terry Hobbs (stepfather of one of the victims) to the crime scene, and new statements from Hobbs' now ex-wife. Also presented in the filing was new expert testimony that the supposed knife marks on the victims, including the injuries to Byers' genitals, were in fact the result of animal predation after the bodies had been dumped.[64]

On September 10, 2008, Circuit Court Judge David Burnett denied the request for a retrial, citing the DNA tests as inconclusive.[65] That ruling was appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments in the case on September 30, 2010.

Arkansas Supreme Court ruling (2010)

On November 4, 2010, the Arkansas Supreme Court ordered a lower judge to consider whether newly analyzed DNA evidence might exonerate the three.[66] The justices also instructed the lower court to examine claims of misconduct by the jurors who sentenced Damien Echols to death and Jessie Misskelley and Jason Baldwin to life in prison.[66]

In early December 2010, David Burnett was elected to the Arkansas State Senate. Circuit Court Judge David Laser was selected to replace David Burnett and preside in the evidentiary hearings mandated by the successful appeal.[67]

Plea deal and release (2011)

After weeks of negotiations, on August 19, 2011, Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley were released from prison as part of a plea deal, making the hearings ordered by the Arkansas Supreme Court unnecessary.[68] The three entered into Alford plea deals. Stephen Braga, an attorney with Ropes & Gray who took up Echols's defense on a pro bono basis beginning in 2009, negotiated the plea agreement with prosecutors.[69]

Under the deal, Judge David Laser vacated the previous convictions, including the capital murder convictions for Echols and Baldwin, and ordered a new trial. Each man then entered an Alford plea to lesser charges of first- and second-degree murder while verbally stating their innocence. Judge Laser then sentenced them to time served, a total of 18 years and 78 days, and they were each given a suspended imposition of sentence for 10 years.[68] If they re-offend they can be sent back to prison for 21 years.[6]

Factors cited by prosecutor Scott Ellington for agreeing to the plea deal included that two of the victims' families had joined the cause of the defense, that the mother of a witness who testified about Echols's confession had questioned her daughter's truthfulness, and that the State Crime Lab employee who collected fiber evidence at the Echols and Baldwin homes after their arrests had died.[70] As part of the plea deal, the three men cannot pursue civil action against the state for wrongful imprisonment.[71]

Many of the men's supporters, and opponents who still believe them guilty, were unhappy with the unusual plea deal.[72] In 2011, supporters pushed Arkansas Governor Mike Beebe to pardon Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley based on their innocence. Beebe said he would deny the request unless there was evidence showing someone else committed the murders.[73] Prosecutor Scott Ellington said the Arkansas state crime laboratory would help seek other suspects by running searches on any DNA evidence produced in private laboratory tests during the defense team's investigation. This would include running the results through the FBI's Combined DNA Index System database.[74] Ellington said that, although he still considered the men guilty, the three would likely be acquitted if a new trial were held because of the powerful legal counsel representing them now, the loss of evidence over time, and the change of heart among some of the witnesses.[68]

Family and law enforcement opinions

The families of the three victims are divided in their opinions as to the guilt or innocence of the West Memphis Three. In 2000, the biological father of Christopher Byers, Rick Murray, expressed his doubts about the guilty verdicts on the West Memphis Three website.[75] In 2007, Pamela Hobbs, the mother of victim Stevie Branch, joined those who have publicly questioned the verdicts, calling for a reopening of the verdicts and further investigation of the evidence.[76] In late 2007, John Mark Byers—who was previously vehement in his belief that Echols, Misskelley, and Baldwin were guilty—also announced that he now believes that they are innocent.[77] "I had made the comment if it were ever proven the three were innocent, I'd be the first to lead the charge for their freedom," said Byers, and take "every opportunity that I have to voice that the West Memphis Three are innocent and the evidence and proof prove they're innocent."[78] Byers has spoken to the media on behalf of the convicted, and has expressed his desire for justice for the families of both the victims and the three accused.[78]

In 2010, district Judge Brian S. Miller ordered Terry Hobbs, the stepfather of victim Stevie Branch, to pay $17,590 to The Chicks (then known as the Dixie Chicks) singer Natalie Maines for legal costs stemming from a defamation lawsuit he filed against the band. Miller dismissed a suit Hobbs filed over Maines' remarks and writings implying that he was involved in killing his stepson. The judge said Hobbs had chosen to involve himself in public discussion over whether the convictions were just.[79]

John E. Douglas, a former longtime FBI agent and current criminal profiler, said that the murders were more indicative of a single murderer intent on degrading and punishing the victims, than of a trio of "unsophisticated" teenagers.[80] Douglas believed that the perpetrator had a violent history and was familiar with the victims and with local geography. Douglas served as FBI Unit Chief of the Investigative Support Unit of the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime for 25 years. He stated in his report for Echols's legal team that there was no evidence the murders were linked to satanic rituals and that post-mortem animal predation could explain the alleged knife injuries. He said that the victims had died from a combination of blunt force trauma and drowning, in a crime which he believed was driven by personal cause.[81]

Documentaries, publications, and studies

Three films, Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills, Paradise Lost 2: Revelations, and Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory, directed by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, have documented this case and are strongly critical of the verdict. The films marked the first time Metallica allowed their music to be used in a movie, which drew attention to the case.[82]

There have been a number of books about the case, also arguing that the suspects were wrongly convicted: Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three by Mara Leveritt, Blood of Innocents by Guy Reel, and The Last Pentacle of the Sun: Writings in Support of the West Memphis Three, edited by Brett Alexander Savory & M. W. Anderson, and featuring dark fiction and non-fiction by well-known writers of speculative fiction. In 2005, Damien Echols completed his memoir, Almost Home, Vol 1, offering his perspective of the case.[83] A biography of John Mark Byers by Greg Day named Untying the Knot: John Mark Byers and the West Memphis Three was published in May 2012.[84]

Many songs were written about the case, and two albums were released in support of the defendants. In 2000, The album Free the West Memphis 3 was released by KOCH Records. Organized by Eddie Spaghetti of the band Supersuckers, the album featured a number of original songs about the case and other recordings by artists such as Steve Earle, Tom Waits, L7, and Joe Strummer. In 2002, Henry Rollins worked with other vocalists from various rock, hip hop, punk, and metal groups and members of Black Flag and the Rollins Band on the compilation album Rise Above: 24 Black Flag Songs to Benefit the West Memphis Three. All money raised from sales of the album was donated to the legal funds of the West Memphis Three. Metalcore band Zao's 2002 album Parade of Chaos included a track inspired by the case named "Free The Three". On April 28, 2011, the band Disturbed released a song entitled "3" as a download on their website. The song is about the West Memphis Three, with 100% of the proceeds going to their benefit foundation for their release.[85]

A website by Martin David Hill, containing approximately 160,000 words and intending to be a "thorough investigation", collates and discusses many details surrounding the murders and investigation, including some anecdotal information.[86]

Investigative journalist Aphrodite Jones undertook an exploration of the case on her Discovery Network show True Crime with Aphrodite Jones following the DNA discoveries. The episode premiered May 5, 2011, with extensive background information included on the show's page at the Investigation Discovery site. In August 2011, White Light Productions announced that the West Memphis Three would be featured on their new program Wrongfully Convicted.[87]

In January 2010, the CBS television news journal 48 Hours aired "The Memphis 3", an in-depth coverage of the history of the case, including interviews with Echols and supporters. On September 17, 2011, 48 Hours re-aired the episode with the update of their release and interviews from Echols and his wife, and Baldwin. Piers Morgan Tonight aired an episode on September 29, 2011, about the three's plans for the future and continued investigations on the case.[88]

West of Memphis, directed and written by Amy J. Berg, and produced by Peter Jackson, as well as by Echols himself, premiered at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival. Actor Johnny Depp, a longtime supporter of the West Memphis Three and personal friend of Damien Echols, was on hand to support the film in its premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2012.[89]

Atom Egoyan directed a feature film of the case based on Mara Leveritt's book, titled Devil's Knot, starring Colin Firth and Reese Witherspoon, which was produced by Worldview Entertainment.[90] The film premiered at the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival and was released in U.S. theaters on May 9, 2014.[91][92]

Defendants

Jessie Misskelley

Jessie Misskelley Jr. (born July 10, 1975) was arrested in connection to the murders of May 5, 1993. After a reported 12 hours of interrogation by police, Misskelley, who has an IQ of 72, confessed to the murders, and implicated Baldwin and Echols. However, the confession was at odds with facts known by police, such as the time of the murders.[6][68] Under the Bruton rule, his confession could not be admitted against his co-defendants and thus he was tried separately. Misskelley was convicted by a jury of one count of first-degree murder and two counts of second-degree murder. The court sentenced him to life plus 40 years in prison. His conviction was appealed and affirmed by the Arkansas Supreme Court.[93]

On August 19, 2011, Misskelley, along with Baldwin and Echols, entered an Alford plea. Judge David Laser then sentenced them to 18 years and 78 days, the amount of time they had served, and also levied a suspended sentence of 10 years. All three were released from prison that same day.[68] Since his release, Misskelley has become engaged to his high school girlfriend and enrolled in a community college to train as an auto mechanic.[94]

Charles Jason Baldwin

Charles Jason Baldwin[95] (born April 11, 1977) along with Misskelley and Echols, entered an Alford plea on August 19, 2011.[6] Baldwin pleaded guilty to three counts of first degree murder while still asserting his actual innocence. The judge then sentenced the three men to 18 years and 78 days, the amount of time they had served, and also levied a suspended sentence of 10 years.

Baldwin was initially resistant to agree to this deal, insisting as a matter of principle that he would not plead guilty to something he did not do. He then realized, he has said, that his refusal would have meant that Echols stayed on death row. "This was not justice," he said of the deal. "However, they're trying to kill Damien."[68] Since his release, Baldwin has moved to Seattle to live with friends. He is in a relationship with a woman who befriended him while he was in prison. He has stated that he plans on enrolling in college to become a lawyer in order to help wrongfully convicted persons prove their innocence.[96] Baldwin said in a 2011 interview with Piers Morgan that he worked for a construction company and he was learning how to drive.[88]

Damien Wayne Echols

Damien Wayne Echols (born Michael Wayne Hutchison,[97] December 11, 1974) was on death row, locked-down 23 hours per day at the Varner Unit Supermax.[3] Echols, ADC# 000931, entered the system on March 19, 1994.[98] From prison in 1999, he married landscape architect Lorri Davis.

On August 19, 2011, Echols, along with Baldwin and Misskelley, was released from prison after their attorneys and the judge handling the upcoming retrial agreed to a deal. Under the terms of the Alford guilty plea, Echols and his co-defendants accepted the sufficiency of evidence supporting the three counts of first degree murder while maintaining their innocence. DNA evidence at the scene was not found to include any from Echols or his co-defendants.[99] He moved to New York City after his release.[100]

Appeal

Echols' mental stability during the years immediately prior to the murders and during his trial was the focus of his appellate legal team in their appeal attempts. In his efforts to win a new trial, Echols, 27 at the time of the appeal, claimed he was incompetent to stand trial because of a history of mental illness. The record on appeal spells out a long history of Echols' mental health problems, including a May 5, 1992, Arkansas Department of Youth Services referral for possible mental illness, a year to the day before the murders.[101] Hospital records for his treatment in Little Rock 11 months before the killings show a history of self-mutilation and assertions to hospital staff that he gained power by drinking blood, that he had inside him the spirit of a woman who had killed her husband, and that he was having hallucinations. He also told mental health workers that he was "going to influence the world."[101]

The appellate legal team argued that Echols did not waive his assertion that he was not mentally competent before his 1994 trial because he was not competent to waive it. To assist in the appeals process, Echols' appellate legal team retained a Berkeley, California-based forensic psychiatrist, Dr. George Woods, to make their case.[102]

Echols' lawyers claimed that his condition worsened during the trial, when he developed a "psychotic euphoria that caused him to believe he would evolve into a superior entity" and eventually be transported to a different world. His psychosis dominated his perceptions of everything going on in court, Woods wrote.[101] Echols's mental state while in prison awaiting trial was also called into question by his appellate team.[citation needed]

Retrial request

While in prison, Echols wrote letters to Gloria Shettles, an investigator for his defense team.[103] Echols sought to overturn his conviction based on trial error, including juror misconduct, as well as the results of a DNA Status Report filed on July 17, 2007, which concluded "none of the genetic material recovered at the scene of the crimes was attributable to Mr. Echols, Echols' co-defendant, Jason Baldwin, or defendant Jessie Misskelley .... Although most of the genetic material recovered from the scene was attributable to the victims of the offenses, some of it cannot be attributed to either the victims or the defendants."[104] Advanced DNA and other scientific evidence – combined with additional evidence from several different witnesses and experts – released in October 2007 had cast strong doubts on the original convictions. A hearing on Echols' petition for a writ of habeas corpus was held in the Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas.[105]

Release

On August 19, 2011, Echols, along with Baldwin and Misskelley, entered an Alford plea, while asserting their innocence.[6] The judge sentenced them to 18 years and 78 days, the amount of time they had served, and levied a suspended sentence of 10 years. Echols' sentence was reduced to three counts of first degree murder. Lawyers representing the West Memphis Three reached the plea deal that allowed the men to be released from prison. They were transferred to the hearing with their possessions. The plea deal did not technically result in a full exoneration; some of the convictions would stand, but the men would not admit guilt. The counsel representing the men said they would continue to pursue full exoneration.[68]

Aftermath

Echols relocated to Salem, Massachusetts, with his wife and has no intentions of returning to Arkansas. In a 2013 interview with Piers Morgan, he said that he would like to have a career in writing and visual arts.[106]

Echols self-published the memoir, Almost Home: My Life Story Vol. 1 (2005), while still in prison.[107] After his release, he has worked on a number of additional media projects.

- Music

-

- Echols co-wrote the lyrics to the song "Army Reserve", on Pearl Jam's self-titled album (2006).[108]

- Echols and punk musician Michale Graves, the latter a former vocalist for Misfits, released an album titled Illusions in October 2007.[109]

- Art

-

- Echols began creating art while on death row as a "side effect of my spiritual, magical practice."[110] The Copro Gallery in Los Angeles exhibited Echols' artwork (March 19 – April 16, 2016).[111] The focus of the exhibit, titled 'SALEM,' draws attention to the comparison between the historical U.S. Salem witch trials and Echols' own experience during a modern-day U.S. witch-hunt known for false accusations of Satanic ritual abuse.

- On March 23, 2016, Echols gave a presentation about his art processes at the Rubin Museum of Art.[112]

- Spoken word

- Written works

-

- Echols' poetry has appeared in the Porcupine Literary Arts magazine (Volume 8, Issue 2).

- He has written non-fiction for the Arkansas Literary Forum.[114]

- Since his release, he has published a non-fiction book about both his childhood and incarceration, Life After Death (2012), which includes material from his 2005 memoir.[115]

- He and Lorri Davis, a NYC landscape architect who initiated a correspondence with Echols in 1999 and ultimately became his wife, co-authored Yours for Eternity: A Love Story on Death Row (2014)[116]

- Television

-

- Echols provided the voice of Darryl, a fish man (i.e., a fish situated on a robot body), in episode 3 of the animated Netflix series The Midnight Gospel (2020).[117]

In August 2021, ten years after release from prison, Echols reiterated that he would not give up seeking any evidence that remained, so it could be retested to exonerate the three and lead to those actually responsible. In response to Echols' requests since early 2020 that remaining evidence undergo specialized DNA testing, officials told his legal team that such evidence had been lost or destroyed years ago in a fire, of which there is no public record. A FOIA request was submitted and the receiving attorney said any evidence testing would have to be ordered by a judge. Echols attorneys filed a Motion for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief in the Circuit Court of Crittendon County First Division, and asked for an expedited hearing.[118][119] In December 2021, Echols' team was able to review remaining evidence and planned to move forward with new testing.[120] In June 2022, a judge rejected a January request for DNA testing of the evidence.[121][122] Echols' lawyers appealed the case to the Arkansas Supreme Court in January 2023. The state said in February that the appeal should be dismissed because the case was initially filed in the wrong county – Crittenden rather than Craighead County, where Echols' conviction was entered. In March, Echols' team responded that such a dismissal reason is irrelevant because both counties are within Arkansas' 2nd Judicial Circuit.[123] In April 2023, the state supreme court ruled in favor of Echols's appeal for DNA testing.[124] In April 2024, the Arkansas Supreme Court again reversed a lower court's order denying Echols' postconviction motion for DNA testing for lack of jurisdiction.[125][126]

See also

- 1991 Austin yogurt shop murders

- Central Park Five

- False confession

- Moral panic

- Norfolk Four

- Witch-hunt (metaphorical usage)

Notes

- ^ In 2011, Echols would reflect that, should investigators attempt to proceed to trial with the same evidence compiled in 1993 and with the external scrutiny which had not then existed, he and his co defendants would not have been brought to trial, stating: "They knew that there would be more people watching this, more attention on this case. They wouldn't be able to pull the same tricks. Basically, when we went to trial the first time, they came in with ghost stories, rumors, innuendo. Really, things that had nothing to do with the case whatsoever."[50]

References

- ^ "Youth Is Convicted In Slaying of 3 Boys In an Arkansas City". The New York Times. February 5, 1994.

The prosecution said the slayings might have been part of a satanic ritual.

- ^ "Arguments conclude in 'West Memphis Three' appeals". Arkansas Online. The Associated Press. October 2, 2009.

Prosecutors claimed the killers sexually mutilated the boy in a satanic ritual.

- ^ a b c d e f Lundin, Leigh (November 14, 2010). "Not-so-cold Old Cases". Capital Punishment. Orlando: Criminal Brief.

- ^ Patrick Doyle (September 1, 2011). "How Rockers Helped Free the West Memphis Three". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ Parker, Suzi (July 27, 2011). "Fresh DNA evidence boosts defense in 1993 Arkansas slayings". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Arkansas Democrat-Gazette (August 19, 2011). "Plea reached in West Memphis murders". ArkansasOnline. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Simon & Schuster. p. 5. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ Blackstone, Ashley (September 30, 2010). "Damien Echols asks for new trial in West Memphis 3 murder case". Today's THV – Gannett. Arkansas Television Company. Retrieved January 25, 2012.; Affidavits[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Atria. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ a b c d e Michael Newton (2009). The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes. Infobase Publishing. p. 391. ISBN 9781438119144. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Frank J. Peretti, William Q. Sturner (May 1993). "Christopher Byers Autopsy" (PDF). Arkansas State Crime Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Frank J. Peretti, William Q. Sturner (May 1993). "Steve Branch Autopsy" (PDF). Arkansas State Crime Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Frank J. Peretti, William Q. Sturner (May 1993). "Michael Moore Autopsy" (PDF). Arkansas State Crime Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Turvey, Brent E. (1999). Criminal profiling:an introduction to behavioral evidence analysis. Academic. p. 377. ISBN 9780123852441. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ "West Memphis Three". commercialappeal.com. 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c Beifuss, John (May 9, 1993). "Pain tells how much life 3 slain boys had". commercialappeal.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ "Police see progress in Ark. murder inquiry". The Commercial Appeal. May 11, 1993. p. B1. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Help sought for memorial to victims in West Memphis 3 case". Arkansas Times. 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ "3 Teen-Agers Accused in the Killings of 3 Boys". New York Times. June 6, 1993. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ Mark Caro, In Search Of Evil, Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1996.

- ^ a b c Leveritt, 2003, p. 27-28

- ^ a b Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Simon & Schuster. pp. 6, 174. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ a b Linder, Douglas O. "Who Killed the Three Boys?". Famous Trials. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Blume, John H.; Helm, Rebecca K. (November 2014). "The Unexonerated: Factually Innocent Defendants Who Plead Guilty". Cornell Law Review. 100 (1). Ithaca: Cornell Law School: 157–192.

- ^ "West Memphis Three". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ^ Schneider, Sydney (2013). "When Innocent Defendants Falsely Confess: Analyzing the Ramifications of Entering Alford Pleas in the Context of the Burgeoning Innocence Movement". Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 103 (1). Chicago: Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law: 279–308.

- ^ Dewan, Shaila (October 30, 2007). "Defense Offers New Evidence in a Murder Case That Shocked Arkansas". The New York Times.

- ^ Monroe, Rachel (September 26, 2018). "Damien Echols and the Secrets of Magick". The New York Times.

- ^ Dunne, Carey (October 27, 2018). "Magick 'Saved My Life': the Former Death Row Inmate Turned Warlock". The Guardian. London: Guardian Media Group.

- ^ [24][25][26][27][28][29]

- ^ "collective – paradise lost, revelations dvd". BBC. July 10, 2005. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Transcript, MissKelley, Jr. Confession

- ^ a b "cr94-848". Arkansas Judiciary. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "WM3 Interview With Dan Stidham, Part 1 of 11". Crime Scene Detectives. May 15, 2010. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Sullivan, Bartholomew (March 19, 1994). "Jury finds Echols, Baldwin guilty of capital murder in killing 3 boys". The Commercial Appeal. Memphis, Tennessee: Scripps Howard.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. "The West Memphis Three Trials: An Account". Famous Trials. UKMC School of Law, University of Missouri–Kansas City.

- ^ Steel, Fiona (March 17, 2006). "The West Memphis 3". Crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "Teens Plead Innocent In Boys' Deaths". Times Daily. August 4, 1993. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Steel, Fiona. "The West Memphis Three". Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Geoffrey (October 13, 2011). "A Death-Row Love Story". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

Then a teenager, Jessie Misskelley Jr., told the police that he saw his friend, Jason Baldwin, and another teenager, Damien Echols, go into the woods with the boys and rape them. Misskelley later recanted

- ^ "Arkansas Teen Found Guilty On Three Counts Of Murder," Gainesville Sun, February 5, 1994

- ^ "Youth Is Convicted In Slaying of 3 Boys In an Arkansas City". The New York Times. February 5, 1994.

- ^ "Miscellaneous Essays and Interviews – David Jauss". www.davidjauss.com. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Sullivan, Bartholomew (March 9, 1994). "Witnesses call boys deaths work of group with trappings of the occult". The Commercial Appeal. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ "Teens Found Guilty In Boys' Slayings". Free Lance-Star. March 19, 1994. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Simon & Schuster. p. 245. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Simon & Schuster. p. 25. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Simon & Schuster. pp. 399, 404. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ "Revelations: Paradise Lost 2. HBO. 28 July 2000 Broadcast. March 17, 2006". IMDb. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ "West Memphis 3: Echols, Baldwin, Misskelley Speak". kait8. August 19, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Appeal puts 3 Ark. boys' murders back in spotlight". Seattle Post Intelligencer. May 5, 1993.

- ^ Misskelley v. State, 323 Ark. 449 Archived March 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 915 S.W.2d 702 (Google Scholar), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 898 (1996); Echols & Baldwin v. State, 326 Ark. 917[permanent dead link], 936 S.W.2d 509 (1996) (Google Scholar), cert. denied, 520 U.S. 1244 (1997).

- ^ Morgan, James (June 7, 1996). "John Grisham, meet Dan Stidham". Arkansas Times.

Stidham has sent off for his credentials to argue before the United States Supreme Court. [...] he continues to prepare the appeal he hopes to make before the U.S. Supreme Court.

- ^ Henry Weinstein, Lawyers file DNA motion in Cub Scout murder case, Los Angeles Times October 30, 2007

- ^ Echols v. State, 2010 Ark. 417 Archived March 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 373 S.W.3d 892 (Google Scholar) (reversing and remanding to reconsider trial court's denial of def't's motion for new trial); Baldwin v. State, 2010 Ark. 412 Archived March 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (Google Scholar) (same); Misskelley v. State, 2010 Ark. 415 Archived March 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (Google Scholar) (same).

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Simon & Schuster. pp. 334–5. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (2003). Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Simon & Schuster. p. 310. ISBN 0-7434-1760-7.

- ^ a b c d Hackler, Tim (October 7, 2004). "Complete Fabrication". Arkansas Times. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ Mara Leveritt and Max Brantley New evidence in West Memphis murders Archived December 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Arkansas Times, July 19, 2007.

- ^ "KAIT: Mother of West Memphis 3 Victim Speaks About New DNA Evidence". Kait8.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Hobbs, Pamela Marie (May 20, 2009). Declaration of Pamela Marie Hobbs. THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS, WESTERN DIVISION, TERRY HOBBS, Plaintiff, v. NATALIE PASDAR, et al., Defendants, CV NO.: 4-09-CV-0008BSM. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Beth Warren, "Jury foreman in West Memphis Three trial of Damien Echols accused of misconduct Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine," Memphis Commercial Appeal, October 13, 2010

- ^ The Associated Press (September 30, 2008). "Former lawyer supports effort for a new trial". Arkansas Online. Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Arkansas Blog: West Memphis 3 Press Conference Archived November 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zeman, Jill (September 10, 2008). "Judge rejects request for new trial for 3 men convicted of 1993 slayings of 3 Arkansas boys". Nesting.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Bleed, Jill Zeman (November 4, 2010). "New hearing ordered for 3 in Ark. scout deaths". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ^ "New judge appointed for West Memphis appeals". Arkansas Online. Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. The Associated Press. December 1, 2010. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robertson, Campbell (August 19, 2011). "Deal Frees 'West Memphis Three' in Arkansas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ Randazzo, Sara. "The Ropes & Gray Partner Who Helped Free the West Memphis Three" (PDF). American Lawyer Daily. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Max Brantley, Prosecutor's statement on West Memphis 3 plea deal Arkansas Times August 19, 2011

- ^ Libby, Karen (August 26, 2011). "West Memphis Three Attorneys Discuss Alford Plea Details". Maxwell S. Kennerly. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (August 19, 2011). "FLASH: West Memphis 3 freed in plea bargain". Arkansas Blog. Arkansas Times. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Bauder, David (October 10, 2011). "West Memphis 3, locked up 18 years, together in NY". Houston Chronicle. Hearst Newspapers. Retrieved January 25, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Demillo, Andrew (August 27, 2011). "Arkansas crime lab to study 'West Memphis 3' case DNA". The Commercial Appeal. Scripps Newspaper Group—Online. Associated Press. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ Rick, Murray (May 2000). "Rick Murray speaks out". Free the West Memphis Three. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007.

- ^ Leveritt, Mara; Brantley, Max (July 19, 2007). "New evidence in West Memphis murders". Arkansas Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Avila, Jim (November 1, 2007). "Father of Victim to Convicted Killer: "I'm Here for You"". ABC News. ABC News Internet Ventures. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Alex Coleman, "Victim's father wants West Memphis 3 set free Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine", WREG, February 26, 2010

- ^ Dixie Chicks' Natalie Maines Wins "West Memphis Three" Defamation Suit, CNN, April 19, 2010

- ^ Warren, Beth (November 7, 2010). "Professional profiler convinced of innocence of West Memphis Three". The Commercial Appeal. Memphis, TN: Scripps Newspaper Group—Online. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Williams, Brittany (October 11, 2017). "Mindhunter: Former FBI unit chief recalls high-profile cases". El Dorado News-Times. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ "Metallica May Give Music To "Paradise Lost" Sequel". MTV. May 28, 1998. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ Echols, Damien (June 3, 2005). Almost Home: My Life Story Vol 1. iUniverse, Inc.

- ^ Greg Day, "Untying The Knot: John Mark Byers and the West Memphis child murders". Retrieved August 21, 2011 Archived June 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Disturbed Release Benefit Single for West Memphis Three". Starpulse.com. April 30, 2011. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Martin David Hill. "Murders in West Memphis". Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ "West Memphis Three 'Wrongully Convicted Episode Trailer White Light Productions' – CNN iReport". CNN. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ a b CNN Wire Staff (September 29, 2011). "Decades without daylight: 'West Memphis Three' describe life in prison". CNN. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Rosenfield, Kat (September 9, 2012). "Johnny Depp Reveals Anguish Over West Memphis Three Injustice". MTV. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (May 16, 2012). "Cannes 2012: Colin Firth, Reese Witherspoon's West Memphis Three Pic Gets Financing (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 21, 2024.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (October 7, 2013). "Image Picks Up West Memphis Three Pic 'Devil's Knot'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 21, 2024.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (February 10, 2014). "West Memphis Three drama 'Devil's Knot' with Reese Witherspoon sets release". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "West Memphis 3 cases to receive hearing, possible new trial". cnn. November 4, 2010. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ^ Dunning, Eric Moore (2012). From courtroom to chatroom: the online social movement to free the "West Memphis Three" (PhD thesis). University of Alabama.

- ^ "ADC Inmate Search – Inmate Details". Arkansas Department of Correction. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011.

Information Current as of 08/09/2011

- ^ Rothbart, Davy (January 12, 2012). "Q&A: Paradise Lost directors Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky". Grantland. ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Perrusquia, Marc (February 27, 1994). "Damien Echols may be troubled but he's not killer, some say". The Commercial Appeal. Memphis. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Echols profile, Arkansas Department of Correction website; retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ^ Dewan, -Shaila (October 30, 2007). "Defense Offers New Evidence in a Murder Case That Shocked Arkansas". The New York Times.

according to long-awaited new evidence ..., there was no DNA from the three defendants found at the scene

- ^ Leveritt, Mara (2011). "The Damien I Know – The Architect and the Inmate". arktimes.com. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c "The Commercial Appeal".

- ^ George Woods Affidavit, google.com; accessed October 5, 2015.

- ^ "CNN Larry King Live-Damien Echols Death Row Interview".

- ^ "DNA TESTING CONCLUDES". wm3.org. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved July 22, 2007.

- ^ Echols' Attorneys File New Motion Claiming Wrongful Conviction In 'West Memphis Three' Case Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, American Chronicles, accessed October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Piers Morgan – Damien Echols On The Death Penalty – 02/08/2013". YouTube. November 13, 2013. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021.

- ^ Echols, Damien (June 3, 2005). Almost Home: My Life Story Vol. 1. iUniverse. ISBN 9780595357017.

- ^ "Ex-Misfits Singer Rocks With West Memphis 3's Echols | Billboard.com". Billboard. 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ "Illusions Album: Michale Graves & Damien Echols". Amazon.

- ^ "L.A. Times article on Damien Echols art exhibit at Copro Gallery". Los Angeles Times. March 24, 2016.

- ^ "SALEM Exhibit of Echols' Artwork at the Copro Gallery".

- ^ "DAMIEN ECHOLS ARTISTS ON ART MARCH 25 6:15 – 7:00 PM".

- ^ The Moth. Hachette Books. 2013. ISBN 9781401311117.

- ^ Arkansas Literary Forum Archived October 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Echols, Damien (2012). Life After Death. Blue Rider Press. ISBN 9780399160202.

- ^ Echols, Damien; Davis, Lorri (June 17, 2014). Yours for Eternity: A Love Story on Death Row. Blue Rider Press. ISBN 9780399166198.

- ^ Fogarty, Paul (April 21, 2020). "The Midnight Gospel: Damien Echols' appearance explained – how the Netlfix voice actor escaped death row". HITC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ "West Memphis Three mark decade out of prison, Echols still seeking answers". Talk Business & Politics. August 19, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via KATV.

- ^ Bowden, Bill (September 13, 2021). "Echols asks judge to force police to follow open-records law in West Memphis Three evidence case". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ "Damien Echols' legal team reviews 'lost' evidence in 1993 murders". The Evening Times. Crittenden County, Arkansas. December 23, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Almasy, Steve (June 23, 2022). "Judge rejects West Memphis Three member's request for new DNA testing". CNN. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Jared, George (January 26, 2022). "Damien Echols asks court to move forward with advanced DNA testing in WM3 case". KUAR. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Bowden, Bill (March 2, 2023). "Don't dismiss appeal, West Memphis Three's Damien Echols urges state Supreme Court". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Scott, Autumn (April 6, 2023). "AR Supreme Court rules in favor of Damien Echols' appeal". WREG. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Supreme Court of Arkansas (April 18, 2024). "Echols v. State 2024 Ark. 61" (PDF). Supreme Court of Arkansas. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Grajeda, Antoinette (April 18, 2024). "Arkansas Supreme Court reverses West Memphis Three ruling, allows for DNA testing". Arkansas Advocate. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

Further reading

- Article

- "WM3 – Jason Baldwin." Arkansas Times. January 14, 2011.

- Video

- "WM3: Life after Prison (Complete Series)." KATV-TV (Channel 7). Ran on October 30 – November 1, 2011, video posted to YouTube on February 7, 2012.

External links

- The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture entry (The Butler Center for Arkansas Studies)

- West Memphis Three at the Court TV Crime Library

- Archive of West Memphis Three reports from Memphis Commercial Appeal

- Chen, Stephanie. "Echols of West Memphis 3 talks about appeal, death row Archived October 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." CNN. September 29, 2010.

- Investigation Collection Archive

- West Memphis Three

- 1993 in Arkansas

- 1993 murders in the United States

- American murderers of children

- American people convicted of murder

- Crimes involving Satanism or the occult

- False confessions

- Law enforcement in Arkansas

- People convicted of murder by Arkansas

- People who entered an Alford plea

- Quantified groups of defendants

- Satanic ritual abuse hysteria in the United States

- Trios

- West Memphis, Arkansas