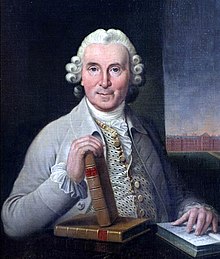

James Lind

James Lind | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 4 October 1716 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 13 July 1794 (aged 77) Gosport, Hampshire, England |

| Education | Royal High School, Edinburgh University of Edinburgh (MD 1748) Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (LRCPE) |

| Known for | Prevention of maritime diseases and cure for scurvy |

| Relatives | James Lind (physician, born 1736) |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Military surgeon |

| Institutions | Surgeon, Royal Navy (1739–1748) Physician, Edinburgh (1748–1758) Senior Physician, Haslar Naval Hospital (1758–1783) |

| Sub-specialties | Naval hygiene |

[1]James Lind FRSE FRCPE (4 October 1716 – 13 July 1794) was a Scottish physician. He was a pioneer of naval hygiene in the Royal Navy. By conducting one of the first ever clinical trials,[2][3] he developed the theory that citrus fruits cured scurvy.

Lind argued for the health benefits of better ventilation aboard naval ships, the improved cleanliness of sailors' bodies, clothing and bedding, and below-deck fumigation with sulphur and arsenic. He also proposed that fresh water could be obtained by distilling sea water. His work advanced the practice of preventive medicine and improved nutrition.

Early life

[edit]Lind was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1716 into a family of merchants, then headed by his father, James Lind. He had an elder sister.[4] He was educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh.[citation needed]

In 1731 he began his medical studies as an apprentice of George Langlands,[5] a fellow of the Incorporation of Surgeons which preceded the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. In 1739, he entered the Navy as a surgeon's mate, serving in the Mediterranean, off the coast of West Africa and in the West Indies.[6] By 1747 he had become surgeon of HMS Salisbury in the Channel Fleet, and conducted his experiment on scurvy while that ship was patrolling the Bay of Biscay. Just after that patrol he left the Navy, wrote his MD thesis on venereal diseases and earned his degree from the University of Edinburgh Medical School, and was granted a licence to practise in Edinburgh.[5]

Legacy

[edit]Prevention and cure of scurvy

[edit]Scurvy is a disease caused by a vitamin C deficiency, but in Lind's day, the concept of vitamins was unknown. Vitamin C is necessary for healthy connective tissue. In 1740 the catastrophic result of then-Commodore George Anson's circumnavigation attracted much attention in Europe; out of 1900 men, 1400 died, most of them allegedly from scurvy. According to Lind, scurvy caused more deaths in the British fleets than French and Spanish arms.[7]

Since antiquity in some parts of the world, and since the 17th century in England, it had been known that citrus fruit had an antiscorbutic effect. John Woodall (1570–1643), an English military surgeon of the British East India Company recommended them[8] but their use did not become widespread. John Fryer (1650–1733) too noted in 1698 the value of citrus fruits in curing sailors of scurvy.[9] Although Lind was not the first to suggest citrus as a cure for scurvy, he was the first to study its effect by a systematic experiment in 1747.[10] It was one of the first reported, controlled, clinical experiments in history, particularly because of its use of control groups.[3]

Lind thought that scurvy was due to putrefaction of the body that could be helped by acids, so he included an acidic dietary supplement in the experiment. This began after two months at sea when the ship was afflicted with scurvy. He divided twelve scorbutic sailors into six groups of two. They all received the same diet, but in addition group one was given a quart of cider daily, group two twenty-five drops of elixir of vitriol (sulfuric acid), group three six spoonfuls of vinegar, group four half a pint of seawater, group five two oranges and one lemon, and the last group a spicy paste plus a drink of barley water. The treatment of group five stopped after six days when they ran out of fruit, but by that time one sailor was fit for duty while the other had almost recovered. Apart from that, only group one showed any effect from its treatment.[citation needed]

Shortly after this experiment, Lind retired from the Navy and practised privately as a physician. In 1753, he published A treatise of the scurvy,[11] that was mostly ignored. In 1758, he was appointed chief physician of the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar at Gosport. When James Cook went on his first voyage he carried wort (0.1 mg vitamin C per 100 g), sauerkraut (10–15 mg per 100 g) and a syrup, or "rob", of oranges and lemons (the juice contains 40–60 mg of vitamin C per 100 g) as antiscorbutics, but only the results of the trials on wort were published. In 1762 Lind's Essay on the most effectual means of preserving the health of seamen appeared.[12] In it he recommended growing salad—i.e. watercress (43 mg vitamin C per 100 g)[13]—on wet blankets. This was put into practice, and in the winter of 1775 the British Army in North America was supplied with mustard and cress seeds. However Lind, like most of the medical profession, believed that scurvy came from ill-digested and putrefying food within the body, bad water, excessive work, and living in a damp atmosphere that prevented healthful perspiration. Thus, while he recognised the benefits of citrus fruit (although he weakened the effect by switching to a boiled concentrate or "rob", in which the boiling process destroys vitamin C), he never advocated citrus juice as a single solution. He believed that scurvy had multiple causes which therefore required multiple remedies.[14]

The medical establishment ashore continued to believe that scurvy was a disease of putrefaction, curable by the administration of elixir of vitriol, infusions of wort and other remedies designed to 'ginger up' the system. It could not account for the effect of citrus fruits and so dismissed the evidence of them as unproven and anecdotal. In the Navy however, experience had convinced many officers and surgeons that citrus juices provided the answer to scurvy, even if the reason was unknown. On the insistence of senior officers, led by Rear Admiral Alan Gardner in 1794, lemon juice was issued on board the Suffolk on a twenty-three-week, non-stop voyage to India. The daily ration of two-thirds of an ounce mixed in grog contained just about the minimum daily intake of 10 mg vitamin C. There was no serious outbreak of scurvy. This resulted in widespread demand for lemon juice, backed by the Sick and Hurt Board whose numbers had recently been augmented by two practical naval surgeons who knew of Lind's experiments with citrus. The following year, the Admiralty accepted the Board's recommendation that lemon juice be issued routinely to the whole fleet.[15] Another Scot, Archibald Menzies, brought citrus plants to Kealakekua Bay in Hawaii on the Vancouver Expedition, to help the Navy re-supply in the Pacific.[16] This was not the end of scurvy in the Navy, as lemon juice was at first in such short supply that it could only be used in home waters under the direction of surgeons, rather than as a preventative. Only after 1800 did the supply increase so that, at the insistence of Admiral Lord St Vincent, it began to be issued generally.[15][17]

Prevention of typhus

[edit]Lind noticed that typhus disappeared from the top floor of his hospital, where patients were bathed and given clean clothes and bedding. However, incidence was very high on the lower floors where such measures were not in place. Lind recommended that sailors be stripped, shaved, scrubbed, and issued clean clothes and bedding regularly. Thereafter, British seamen did not suffer from typhus, giving the British navy a significant advantage over the French.[18]

Fresh water from the sea

[edit]In the 18th century ships took along water, cordial and milk in casks. According to the Regulations and Instructions relating to His Majesty's Service at Sea, which had been published in 1733 by the Admiralty, sailors were entitled to a gallon of weak beer daily (5/6 of a British gallon, equivalent to the modern American gallon or slightly more than three and a half litres). As the beer had been boiled in the brewing process, it was reasonably free from bacteria and lasted for months, unlike water. In the Mediterranean, wine was also issued, often fortified with brandy.[citation needed][19]

A frigate with 240 men, with stores for four months, carried more than one hundred tons of drinkable liquid. Water quality depended on its source, the condition of casks and for how long it had been kept. In normal times, sailors were not allowed to take any water away. When water was scarce, it was rationed and rain collected with spread sails. Fresh water was also obtained when possible en voyage, but watering places were often marshy, and in the tropics infested with malaria.[citation needed]

In 1759, Lind discovered that steam from heated salt water was fresh. He proposed to use solar energy for the distillation of water. But only when a new type of cooking stove was introduced in 1810 was production of fresh water by distillation possible on a useful scale.[citation needed]

Tropical disease

[edit]Lind's final work was published in 1768; the Essay on Diseases Incidental to Europeans in Hot Climates, with the Method of Preventing their fatal Consequences. It was a work on the symptoms and treatments of tropical disease, but was not specific to naval medicine and served more as a general text for doctors and British emigrants. The Essay was used as a medical text in Britain for fifty years following publication. Seven editions were printed, including two after Lind's death.[20]

Family

[edit]Lind married Isabella Dickie and had two sons, John and James. In 1773 he was living on Princes Street in a brand-new house facing Edinburgh Castle.[21]

John FRSE (1751–1794), his elder son, studied medicine at St Andrews University and graduated in 1777,[22] then succeeded his father as chief physician at Haslar Hospital in 1783. James (1765–1823), also embarked on a career with the British navy.[23] His cousin was James Lind (1736–1812).[24]

James rose to the rank of post-captain, and was notable for his role in the Battle of Vizagapatam in the Bay of Bengal in 1804, for which he was knighted.[23]

Death

[edit]Lind died at Gosport in Hampshire in 1794.[25] He was buried in St Mary's Parish Churchyard in Portchester.[26]

Recognition

[edit]

Lind's is one of twenty-three names on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine building in Keppel Street, London. Names were selected by a committee of unknown constitution who deemed them to be pioneers in public health and tropical medicine.[27] At University of Edinburgh Medical School there is the James Lind commemorative plaque unveiled in 1953, funded by citrus growers of California and Arizona.[28] The James Lind Alliance is named after him.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ "Beer on Board in the Age of Sail – Smithsonian Libraries and Archives / Unbound". Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Simon, Harvey B. (2002). The Harvard Medical School guide to men's health. New York: Free Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-684-87181-5.

- ^ a b Baron, Jeremy Hugh (2009). "Sailors' scurvy before and after James Lind - a reassessment". Nutrition Reviews. 67 (6): 315–332. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00205.x. PMID 19519673.

- ^ Bown, Stephen (2003). Scurvy. Summersdale. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-84024-357-4.

- ^ a b Dunn, Peter (1997). "James Lind (1716–94) of Edinburgh and the treatment of scurvy". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 76 (1). United Kingdom: British Medical Journal Publishing Group: 64–65. doi:10.1136/fn.76.1.F64. PMC 1720613. PMID 9059193.

- ^ "James Lind (1716–1794)". British Broadcasting Corporation. January 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Bown, Stephen R. (2003). Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-31391-8

- ^ Rogers, Everett M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: The Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-2209-1. Page 7.

- ^ Wujastyk, Dominik (2005). "Change and Creativity in Early Modern Indian Medical Thought". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 33 (1): 96. doi:10.1007/s10781-004-9056-0. ISSN 0022-1791. PMC 2633698. PMID 19194517.

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney (2004). Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries, John Wiley & Songs, Inc., New Jersey. p. 393. ISBN 0-471-24410-4.

- ^ Lind, James (1753). A Treatise of the Scurvy in Three Parts. Containing an Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease; Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject (1st ed.). Edinburgh: A. Kincaid and A. Donaldson – via Internet Archive.; (2nd ed., 1757); (3rd ed. 1772)

- ^ James Lind (1762). An Essay on the Most Effectual Means of Preserving the Health of Seamen in the Royal Navy: Containing Directions Proper for All Those who Undertake Long Voyages at Sea ... D. Wilson. pp. 4–.

- ^ "FoodData Central".

- ^ Bartholomew, M. (2002). "James Lind and scurvy: A revaluation". Journal for Maritime Research. 4: 1–14. doi:10.1080/21533369.2002.9668317. PMID 20355298. S2CID 42109340.

- ^ a b Vale, B. (2008). "The Conquest of Scurvy in the Royal Navy 1793–1800: A Challenge to Current Orthodoxy". The Mariner's Mirror. 94 (2): 160–175. doi:10.1080/00253359.2008.10657052. S2CID 162207993.

- ^ Speakman, Cummins; Hackler, Rhoda (1989). "Vancouver in Hawaii". Hawaiian Journal of History. 23. Hawaiian Historical Society, Honolulu. hdl:10524/121.

- ^ Macdonald, Janet (2006). Feeding Nelson's Navy. The True Story of Food at Sea in the Georgian Era. Chatham, London. ISBN 1-86176-288-7, pp. 154–166.

- ^ Baumslag, Naomi (2005). Murderous medicine. Greenwood. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-275-98312-3.

- ^ "Beer on Board in the Age of Sail – Smithsonian Libraries and Archives / Unbound". Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Lloyd, Christopher, ed. (1965). The Health of Seamen: Selections from the Works of Dr. James Lind, Sir Gilbert Blane and Dr. Thomas Trotter. London: Navy Records Society. p. 4. OCLC 469895754.

- ^ Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1773–74

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ a b Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. pp. 227–228. ISBN 1-86176-244-5.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Dunn, Peter M. (1997). "James Lind (1716-94) of Edinburgh and the treatment of scurvy". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 76 (1): F64–F65. doi:10.1136/fn.76.1.f64. PMC 1720613. PMID 9059193.

- ^ Wikenden, Jane (December 2012). "The strange disappearances of James Lind". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 105 (12): 535–537 – via National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Behind the frieze | LSHTM". LSHTM. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Gaw, Allan (2011). On moral grounds : lessons from the history of research ethics. Michael H. J. Burns. Glasgow: SA Press. ISBN 978-0-9563242-2-1. OCLC 766246011.

- ^ "History | James Lind Alliance". www.jla.nihr.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

External links

[edit]- James Lind Library (including biography and extracts from Lind's most important works)

- The Lind pages with reference to the Lind family in general including a family tree and other family documents

- James Lind Institute creates future bellwethers of clinical research industry and carries forward the legacy of James Lind

- James Lind at Find a Grave

- 1716 births

- 1794 deaths

- Medical doctors from Edinburgh

- Vitamin C

- 18th-century Scottish medical doctors

- Clinical research

- Scottish surgeons

- Founder fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Members of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh

- Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

- People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- Royal Navy Medical Service officers

- Military personnel from Edinburgh