Jamaica ginger

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

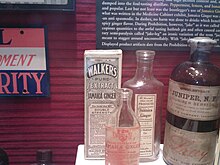

Jamaica ginger extract, known in the United States by the slang name Jake, was a late 19th-century patent medicine that provided a convenient way to obtain alcohol during the era of Prohibition, since it contained approximately 70% to 80% ethanol by weight.[1][2] In the 1930s, a large number of users of Jamaica ginger were afflicted with a paralysis of the hands and feet that quickly became known as Jamaica ginger paralysis or jake paralysis.[1][2]

Composition

[edit]While Jamaica ginger was essentially an infusion of ginger, the US government required solids to be added with the intention of making it less palatable as a way to obtain alcohol legally. The solids expected to be added were particles of ginger root, which made the "medicine" unpalatable. Manufacturers sought solids which impaired the taste less; tricresyl phosphate was used, which the producers later found to be a potent neurotoxin; adulterated Jake is estimated to have caused 30,000 to 50,000 people to lose function in their limbs. Trust in Jamaica Ginger was lost, and its production was discontinued.[3]

Early use and Prohibition

[edit]Since the 1860s, Jamaica ginger had been widely sold at drug stores and roadside stands in two-ounce (57 g) bottles.[1][2][4] In small doses, mixed with water, it was used as a remedy for headaches, upper respiratory infections, menstrual disorders, and intestinal gas.[1][2] Despite its strong ginger flavour, it was popular as an alcoholic beverage in dry counties in the United States, where it was a convenient and legal method of obtaining alcohol.[1] It was often mixed with a soft drink to improve the taste.[1]

When Prohibition was enacted in 1920, sale of alcohol became illegal nationwide, prompting consumers to search for substitutes.[5] Patent medicines with a high alcohol percentage, such as Jamaica ginger, became obvious choices, as they were legal and available over the counter without prescriptions. By 1921, the United States government made the original formulation of Jamaica ginger prescription-only.[6] Only a fluid extract version defined in the United States Pharmacopeia, with a high content of bitter-tasting ginger oleoresin, remained available in stores.[1][6] Because of the taste, it was classified as nonpotable, and was therefore legal to sell despite the alcohol content.[1]

United States Department of Agriculture agents audited Jamaica ginger manufacturers by boiling samples and weighing the resulting solids, to make sure their products contained sufficiently high quantities of the bitter-tasting ginger.[4] To make their products more palatable, manufacturers of Jamaica ginger began to illegally replace the ginger oleoresin with cheaper ingredients like molasses, glycerin, and castor oil, cutting costs and significantly diminishing the unpleasant ginger flavor.[1][4]

Victims

[edit]Organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy

[edit]When the price of castor oil increased in the latter portion of the 1920s, Harry Gross, president of Hub Products Corporation, sought an alternative additive for his Jamaica ginger formula. He discarded ethylene glycol and diethylene glycol as being too volatile, eventually selecting a mixture containing triorthocresyl phosphate (TOCP), a plasticizer used in lacquers and paint finishing. Gross was advised by the manufacturer of the mixture, Celluloid Corporation, that it was non-toxic.[4][7]

TOCP was originally thought to be non-toxic; however, it was later determined to be a neurotoxin that causes axonal damage to the nerve cells in the nervous system of human beings, especially those located in the spinal cord. The resulting type of paralysis is now referred to as organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy, or OPIDN.[8]

In 1930, large numbers of Jake users began to find they were unable to use their hands and feet.[9] Some victims could walk, but they had no control over the muscles which would normally have enabled them to point their toes upward. Therefore, they would raise their feet high with the toes flopping downward, which would touch the pavement first followed by their heels. The toe first, heel second pattern made a distinctive "tap-click, tap-click" sound as they walked. This very peculiar gait became known as the jake walk and the jake dance and those afflicted were said[10] to have jake leg, jake foot, or jake paralysis. Additionally, the calves of the legs would soften and hang down and the muscles between the thumbs and fingers would atrophy.

Within a few months, the TOCP-adulterated Jake was identified as the cause of the paralysis,[11] and the contaminated Jake was recovered. But by that time, it was too late for many victims. Some did recover full, or partial, use of their limbs. But for most, the loss was permanent. The total number of victims was never accurately determined, but is frequently quoted as between 30,000 and 50,000. Many victims were immigrants to the United States, and most were poor, with little political or social influence. The victims received very little assistance.[citation needed] Harry Gross and his part-owner of Boston-Hub Products, Max Reisman, were ultimately fined $1,000 each and given a two-year suspended jail sentence.[11]

Several blues songs on the subject were recorded in the early 1930s, such as "Jake Walk Papa" by Asa Martin, and "Jake Liquor Blues" by Ishman Bracey.[7]

Although this incident became well known,[citation needed] later cases of organophosphate poisoning occurred in Germany, Spain, Italy, and, on a large scale, in Morocco in 1959, where cooking oil adulterated with jet engine lubricant from an American airbase led to paralysis in approximately 10,000 victims, and caused an international incident.[12]

Cultural references

[edit]Books

[edit]- In Sara Gruen's 2006 novel Water for Elephants jake paralysis afflicts one character, Camel, after drinking contaminated Jamaica Ginger.

- In the novel The Black Dahlia, the protagonist reveals early on that his mother went blind and fell to her death after drinking jake, leading to his resentment of his father for purchasing it.

- In his autobiography On the Move: A Life, Oliver Sacks describes research that he conducted to develop an animal model of jake paralysis. He was able to duplicate the toxic effects of TOCP on myelinated neurons in earthworms and chickens.

- In Jamie Ford's novel Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet the two young characters Henry and Keiko are given a prescription for Jamaican Ginger in the 1942 portion of the story. They go to the pharmacy, pick up the bottles, and return to the Black Elks club. Due to war rationing and systemic oppression at the time, the black jazz club is not allowed to have a liquor license, so the proprietor uses Jamaican Ginger to make bathtub gin.

Music

[edit]Songs were recorded at the time about "jake" and its effects; in a variety of musical styles, including blues and country. Several have been included on the compilation albums Jake Walk Blues (1977, 14 songs)[13] and Jake Leg Blues (1994, 16 songs)[14][15] There is a marked but unsurprising duplication of songs between those albums. In some cases, different artists used the same title for different songs. The songs on one or both of those albums are, in alphabetic order by title:

- "Alcohol and Jake Blues" – Tommy Johnson (1930, Paramount 12950) [16][17][18][19]

- "Bay Rum Blues" - David McCarn and Howard Long [20]

- "Bear Cat Papa Blues" – Gene Autry and Frankie Marvin (1931, unreleased) [21][22]

- "Beer Drinkin' Woman" - Black Ace

- "Got the Jake Leg Too" - The Ray Brothers (1930, Victor V-23508) [23]

- "Jake Bottle Blues" - Lemuel Turner (1928, Victor V-40052) [24][25]

- "Jake Head Boogie" - Lightnin' Hopkins (c. 1949-1950)

- "Jake Jigga Juke" - Iron Mike Norton (2005, GFO Records)[26]

- "Jake Leg Blues" - Willie ("Poor Boy") Lofton (1935, Decca 7076) [27]

- "Jake Leg Blues" - Mississippi Sheiks with Bo Carter (1930, Okeh 8939) [28][29][30]

- "Jake Leg Rag" - W. T. ("Willie") Narmour and S. W. ("Shell" or "Shellie") Smith [31][32]

- "Jake Leg Wobble" - The Ray Brothers (1930, Victor V-40291) [33]

- "Jake Legs Blues" - Maynard Britton

- "Jake Legs Blues" - Byrd Moore [34]

- "Jake Liquor Blues" - Ishmon Bracey (1929, Paramount 12941) [35][36][37]

- "Jake Walk Blues" - The Allen Brothers (1931, Victor V-40303) [38][39][40]

- "Jake Walk Blues" - Maynard Britton

- "Jake Walk Papa" - Asa Martin (1933) [41]

- "Limber Neck Rag" - W. T. Narmour and S. W. Smith

Other musical references include:

- Savannah, Georgia-based band Baroness recorded a song called "Jake Leg" for their album Blue Record.

Film and television

[edit]- Jamaica ginger ("Ginger Jake") is a plot element in two episodes of The Untouchables, an American TV series.[42] "The Jamaica Ginger Story" aired in season 2 on February 2, 1961.[43] "Jake Dance" aired on January 22, 1963.[44]

- "Ginger Jake" also makes an appearance in the movie Quid Pro Quo, where "wannabes" (people who would like to be disabled) are helped by Ginger Jake to become disabled.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Parascandola, John (May–June 1995). "The Public Health Service and Jamaica Ginger Paralysis in the 1930s". PHS Chronicles. 110 (3): 361–363. PMC 1382135. PMID 7610232.

- ^ a b c d Gussow, Leon (October 2004). "The Jake Walk and Limber Trouble: A Toxicology Epidemic". Emergency Medicine News. 26 (10): 48. doi:10.1097/00132981-200410000-00045. ISSN 1054-0725.

- ^ O'Neil, Darcy (May 29, 2011). "Jamaica Ginger aka 'Jake'". Art of Drink - Exploring the World One Drink at a Time since 2005. Retrieved October 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Frederick Rowe (November 28, 2014). Banned: A History of Pesticides and the Science of Toxicology. Yale University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780300210378.

- ^ Gage, Beverly (April 2005). "Just What the Doctor Ordered". Smithsonian. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Magnaghi, Russell M. (July 10, 2017). Prohibition in the Upper Peninsula: Booze & Bootleggers on the Border. Arcadia Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 9781625856968.

- ^ a b Davis 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Parascandola 1995, p. 362.

- ^ Phillips, Mary (December 14, 2010). "Jake-leg epidemic first reported by Oklahoma City doctors". Oklahoman.com. The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019.

- ^ "The Jake Walk Effect", ibiblio.org, archived from the original on April 28, 2020

- ^ a b Fortin, Neal (September 28, 2020). "Jamaican Ginger Paralysis - Institute for Food Laws and Regulations". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ Segalla, Spencer David (2012). "The 1959 Moroccan oil poisoning and US Cold War disaster diplomacy". The Journal of North African Studies. 17 (2): 315–336. doi:10.1080/13629387.2011.610118. S2CID 144007393.

- ^ Various – Jake Walk Blues, Stash Records ST 110 at Discogs

- ^ Various – Jake Leg Blues, Jass Records J-CD-642 at Discogs

- ^ Various Artists: Jake Leg Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Tommy Johnson discography". Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Tommy Johnson – Alcohol And Jake Blues / Ridin' Horse at Discogs

- ^ Tommy Johnson: Alcohol and Jake Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Tommy Johnson: Alcohol And Jake Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Howard Long / David McCarn: Bay Rum Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ George-Warren, Holly (February 5, 2009). Public Cowboy No. 1: The Life and Times of Gene Autry. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0195372670. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Gene Autry: Bear Cat Papa Blues". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ The Ray Brothers: Got the Jake Leg Too at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Lemuel Turner discography". Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Lemuel Turner: Jake Bottle Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Jake Jigga Juke: The Story Of A Song - Iron Mike Norton Official Website". Iron Mike Norton Official Website. November 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ "Willie 'Poor Boy' Lofton discography". Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Mississippi Sheiks discography". Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Bo Carter / Mississippi Sheiks: Jake Leg Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Mississippi Sheiks: Jake Leg Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Narmour & Smith / William T. Narmour / Shellie W. Smith: Jake Leg Rag at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Narmour & Smith: Jake Leg Rag at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ The Ray Brothers: Jake Leg Wobble at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Byrd Moore: Jake Legs Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Ishmon Bracey discography". Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Ishman Bracey: Jake Liquor Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Ishman Bracey / Charley Taylor: Jake Liquor Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Allen Brothers – Jake Walk Blues at Discogs

- ^ Allen Brothers: Jake Walk Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Allen Brothers / The Allen Brothers: Jake Walk Blues at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Jake Walk Papa at AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Staff Writer, "The Jamaica Ginger Story", TV.com, Date Unknown

- ^ Peyser, John (February 2, 1961), The Jamaica Ginger Story (Action, Crime, Drama), Robert Stack, Michael Ansara, James Coburn, Alfred Ryder, Desilu Productions, Langford Productions, retrieved January 3, 2021

- ^ Butler, Robert (January 22, 1963), Jake Dance (Action, Crime, Drama), Robert Stack, Dane Clark, Joseph Schildkraut, John Gabriel, Desilu Productions, Langford Productions, retrieved January 3, 2021

Further reading

[edit]- Baum, Dan, "Jake Leg", The New Yorker September 15, 2003, p. 50-57. (PDF)

- Blum, Deborah. The Poisoner's Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York (Penguin Press, February 18, 2010)

- Burns, Eric. The Spirits of America: A Social History of Alcohol (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003) pp. 221–223

- Kidd, J. G, and Langworthy, O. R. Jake paralysis. Paralysis following the ingestion of Jamaica ginger extract adulterated with triortho-cresyl phosphate. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1933, 52, 39.

- Gussow, Leon MD. The Jake Walk and Limber Trouble: A Toxicology Epidemic. Emergency Medicine News"". 26(10):48, October 2004. [1]

- Morgan, John P. and Tulloss, Thomas C. The Jake Walk Blues: A toxicological tragedy mirrored in popular music. JEMF (John Edward s Memorial Foundation) Quarterly, 1977, 122-126.

- Sara Gruen (2006). Water for Elephants : A Novel. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books. ISBN 1-56512-499-5.

- U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Neurotoxicity: Identifying and Controlling Poisons of the Nervous System, OTA-BA-436 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1990).

- Kearney, Paul W. Our Food and Drug G-Men The Progressive July 10, 1944

External links

[edit]- The Epidemiologic Side of Toxicology (slides 6 - 10 deal with the Jamaica Ginger Epidemic)

- Songs about jake leg.

- The Jake Leg Infamy. This film was originally shown September 2009, at the North American College of Clinical Toxicology meeting in San Antonio, TX. It was part of the Toxicology Historical Society component. It has a Standard YouTube License.