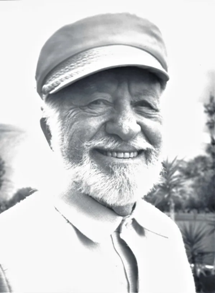

Irving Mills

Irving Mills | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Isadore Minsky January 16, 1894 |

| Died | April 21, 1985 (aged 91) Palm Springs, California, United States |

| Other names | Goody Goodwin, Joe Primrose |

| Occupations |

|

Irving Harold Mills (born Isadore Minsky; January 18, 1894 Odessa, Ukraine – April 21, 1985) was a music publisher, musician, lyricist, and jazz promoter. He often used the pseudonyms Goody Goodwin and Joe Primrose.

Personal life

[edit]Mills was born to a Jewish family[1] in Odessa, Russian Empire, although some biographies state that he was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan[2] in New York City.[a][3] His father, Hyman Minsky, was a hatmaker who immigrated from Odessa to the United States with his wife Sofia (née Dudis).[4] Hyman died in 1905, and Irving and his brother, Jacob (1891–1979) worked odd jobs including bussing at restaurants, selling wallpaper, and working in the garment industry. By 1910, Mills was a telephone operator.

Mills married Beatrice ("Bessie") Wilensky[5] in 1911, and they subsequently moved to Philadelphia. By 1918, Mills was working for publisher Leo Feist. His brother, Jack, was working as a manager for McCarthy and Fisher, the music publishing firm of lyricist Joseph McCarthy and songwriter Fred Fisher.

He died in Palm Springs, California in 1985 at age 91.

Mills Music

[edit]In July 1919 Irving's older brother Jack Mills founded Jack Mills Music;[6][7] mainly motivated to do so out of a desire to publish his own songs. Soon after, he was joined in the enterprise by Irving Mills[8] who served as vice-president of the company with Jack as president, and Samuel Jesse Buzzell as secretary and counselor. The company was renamed Mills Music, Inc. in 1928.[3][9][10] Mills Music acquired the bankrupt Waterson, Berlin & Snyder, Inc. in 1929. Buzzell's son, Loring Buzzell, briefly worked for the company from March 1949 to October 1950.[11][12]

Irving, Jack, and Samuel sold Mills Music on February 25, 1965, to Utilities and Industries Corporation (a utility company based in New York).[13] In 1969, Utilities and Industries Corporation merged Mills Music with Belwin, another music publisher, to form Belwin-Mills.[14] Educational publisher Esquire Inc. announced its acquisition of Belwin-Mills in 1979.[15] Gulf & Western acquired Esquire Inc. in 1983 and sold the Belwin-Mills print business to Columbia Pictures Publications (CPP) in 1985.[16] CPP was later acquired by Filmtrax and Filmtrax was acquired by EMI Music Publishing in 1990.[17] In 1994, Warner Bros. Publications expanded its print music operations by acquiring CPP/Belwin, the print operations of Belwin-Mills.[18] In 2005 Alfred Music acquired Warner Bros. Publications (including Belwin-Mills) from Warner Music Group.[19]

The Mills Music catalog is now managed by Sony Music Publishing, which acquired EMI Music Publishing in 2012.[20]

The Mills Music Trust

[edit]Utilities and Industries Corporation restructured Mills Music as The Mills Music Trust. At the time of the sale, its top 10 earning compositions were:

- "Stardust"

- "When You're Smiling"

- "The Syncopated Clock"

- "Moonglow"

- "Sleigh Ride"

- "I Can't Give You Anything But Love, Baby"

- "Caravan"

- "Blue Tango"

- "Mood Indigo"

- "Who's Sorry Now?"

By the end of 1963, 114 titles brought in 77 percent of the royalty income for five years. The total number of compositions, at the time of sale, was estimated to be in excess of 25,000, of which 1,500 were still producing royalties. In 1964, Mills had royalties of $1.3 million (equivalent to $13,075,790 in 2023). The company had 20 music publishing subsidiaries as well as publishing concerns in Britain, Brazil, Canada, France, West Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, and Spain.[21]

Structure

[edit]The Mills Music Trust traded in units OTC (over-the-counter) under the symbol MMTRS. The trust received payments from EMI Records based on a formula that changed in 2010, when the trust passed almost all its funds to unit holders.

Collaborations

[edit]Mills discovered a number of songwriters, including Zez Confrey, Sammy Fain, Harry Barris, Gene Austin, Hoagy Carmichael, Jimmy McHugh, and Dorothy Fields. He advanced or even started the careers of Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Ben Pollack, Jack Teagarden, Benny Goodman, Will Hudson,[b] and Raymond Scott.

Mills started the studio recording group Irving Mills and his Hotsy Totsy Gang with Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang, Arnold Brillhardt (clarinet, soprano and alto sax),[c] Arthur Schutt, and Mannie Klein. Other variations of his band featured Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and Red Nichols (Mills gave Red Nichols the tag "and his Five Pennies.")

In 1932, Mills founded the Rhythmakers recording group as a vehicle to record and promote jazz singer Billy Banks. The group was a racially integrated ensemble at a time when such groups were legally banned from public theatres, and it included several highly regarded jazz musicians, including Red Allen, Jack Bland, Pee Wee Russell, Fats Waller, Eddie Condon, and Jimmy Lord.[22]

Duke Ellington

[edit]One evening circa 1925, Mills went to a small club on West 49th Street between 7th Avenue and Broadway called the Club Kentucky, often referred to as the Kentucky Club, formerly the Hollywood Club.[23] The owner had brought in a small band of six musicians from Washington, D.C., and wanted to know what Mills thought of them. Mills stayed the rest of the evening listening to the band, Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra. Apparently, Mills signed Ellington the next day. They made numerous records together, not only under the name of Duke Ellington, but also using groups that incorporated Duke's sidemen.

Mills managed Ellington from 1926 to 1939. In his contract with Ellington, Mills owned 50% of Duke Ellington Inc. and thus got a credit for tunes that became popular standards: "Mood Indigo", "(In My) Solitude", "It Don't Mean A Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)", "Sophisticated Lady", and others. He also pushed Ellington to record for Victor, Brunswick, Columbia, Banner, Romeo, Perfect, Melotone, Cameo, Lincoln, Hit of the Week Records, and others. Mills sometimes used a ghostwriter to complete his lyric ideas and sometimes built on their ideas. He was instrumental in Duke Ellington being hired by the Cotton Club.

Mills was one of the first to record black and white musicians together, using twelve white musicians and the Duke Ellington Orchestra on a 12-inch 78 rpm record featuring the "St. Louis Blues" on one side and a medley of songs called "Gems from Blackbirds of 1928" on the other, on which Mills sang with the Ellington Orchestra. Victor Records initially hesitated to release the record, but when Mills threatened to take his artists off their roster, he won out.[24]

Mills formed the Mills Blue Rhythm Band as a relief band at the Cotton Club. Cab Calloway and his band brought a new song into the Cotton Club that Mills co-wrote with Calloway and Clarence Gaskill called "Minnie the Moocher".[25]

Innovations

[edit]Band within a band concept

[edit]One of Mills' most significant innovations was the "band within a band" concept, recording small group sides. He started this in 1928 by arranging for members of Ben Pollack's band to make records under an array of pseudonyms on dime store labels — like Banner, Oriole, Cameo, Domino, and Perfect — while Pollack had an exclusive contract with Victor. A number of these records are considered jazz classics by collectors. Mills printed "small orchestrations," transcribed off the record, so that non-professional musicians could see how great solos were constructed. This was later done by Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and several other bands.

Booking company

[edit]Irving formed the Mills Artists Booking Company. In 1934, he formed an all-female orchestra, headed by Ina Ray. He added Hutton to her name and it became the popular Ina Ray Hutton and her Orchestra.

Music publishing

[edit]In 1934, Mills Music also began a publishing subsidiary, Exclusive Publications, Inc., specializing in orchestrations by songwriters like Will Hudson,[b] who co-wrote the song "Mr. Ghost Goes to Town" with Mills and Mitchell Parish in 1936.

Record labels

[edit]In late 1936, with involvement by Herbert Yates of the American Record Corporation (ARC), Mills founded the Master and Variety labels, which were distributed by ARC through their Brunswick and Vocalion label sales staff. (Mills was previously involved in A&R for Columbia in 1934–36, after ARC purchased the failing label.) Irving signed Helen Oakley Dance to supervise small group records for the Variety label. From December 1936 through to September 1937, 40 records were issued on Master and 170 on Variety. Master's best-selling artists were Duke Ellington, Raymond Scott, Hudson-De Lange Orchestra, Casper Reardon, and Adrian Rollini. Variety's roster included Cab Calloway, Red Nichols, the small groups from Ellington's band led by Barney Bigard, Cootie Williams, Rex Stewart, and Johnny Hodges, as well as Noble Sissle, Frankie Newton, The Three Peppers, Chu Berry, Billy Kyle, and other jazz and pop performers around New York.

By late 1937, multiple problems caused the collapse of these labels. The Brunswick and Vocalion sales also had problems with competition from Victor and Decca. Mills tried to arrange to get his music issued in Europe, but was unsuccessful. After the collapse of the labels, titles that were still selling on Master were reissued on Brunswick and those still selling on Variety were reissued on Vocalion. Mills continued his M-100 recording series after the labels were taken over by ARC, and after cutting back recording to just the better-selling artists, new recordings made from January 1938 by Master were issued on Brunswick (and later Columbia) and Vocalion (later the revived Okeh) until May 7, 1940. Beginning March 8, 1939, in an Ellington session, the prefix "W" was added to matrices (e.g., WM-990 and WM-991). This matrix series was then used until WM-1150, the final being a session by the Adrian Rollini Trio performing "The Girl With the Light Blue Hair," Voc/Okeh 5979, May 7, 1940, New York City. There were 1,055 sessions in the series.[26]

Mills became the head of the American Recording Company, which is now Columbia Records. At one point, Mills was singing at six radio stations seven days a week. Jimmy McHugh, Sammy Fain, and Gene Austin took turns being his pianist.

Filmography

[edit]He produced one film, Stormy Weather, for 20th Century Fox in 1943, which starred Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, Zutty Singleton, Fats Waller, and dancers the Nicholas Brothers and Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. He had a contract to do other movies but found it "too slow," so he continued finding, recording, and plugging music.[citation needed]

Selected recording artists

[edit]Among the artists Mills personally recorded were:

- Irving Aaronson and his Commanders

- Vic Berton's Orchestra

- Billy Banks Orchestra

- Cab Calloway Orchestra

- Chocolate Dandies

- Duke Ellington and his Orchestra

- Frank Froeba Orchestra

- Sonny Greer and his Memphis Men

- Ina Ray Hutton and Her Melodears

- Jimmie Lunceford

- Wingy Manone Orchestra

- Red McKenzie

- Red Nichols & His Five Pennies

- Louis Prima Orchestra

- Chuck Richards

- Joe Venuti

- Will Hudson[b]–Eddie DeLange Orchestra

- Lud Gluskin Orchestra

- Red Norvo & His Swing Septet

- Rex Stewart Orchestra

- Benny Carter Orchestra

- Buster Bailey Orchestra

- Joe Haymes Orchestra

- Mannie Klein Orchestra

Notes

[edit]- ^ U.S. records reflect that Irving Mills was born in Russia, more specifically, Odessa, Ukraine.

- ^ a b c Will Hudson (né Arthur Murray Hainer; 1908–1981) was a composer

- ^ Arnold Brillhardt (né Arnold Ross Brilhart; 1904–1998), saxophonist, married (around 1933) Verlye Mills Davis (maiden; 1911–1983) a harpist; they divorced in 1966

Works cited

[edit]- ^ Cherry, Robert; Griffith, Jennifer (Summer 2014). "Down to Business: Herman Lubinsky and the Postwar Music Industry". Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1-24.

- ^ "Jazz publisher Irving Mills, collaborated with Ellington" (PDF). Gannett Westchester Newspapers. April 22, 1985. p. 4. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Edwards, Bill. "Jack Mills". RagPiano.com. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Sophie Mills (Dudis) (1870–1945)". Geni.com. March 17, 2021.

- ^ "Bessie Mills – U.S. Social Security Death Index (SSDI)". Myheritage.com. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Sanjek, David (2003). "Mills Music". In Shepherd, John (ed.). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World Part 1 Media, Industry, Society, Volume I. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0826463227.

- ^ Jasen, David A. (2004). "Mills Music Inc.". Tin Pan Alley: An Encyclopedia of the Golden Age of American Song. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781135949006.

- ^ Pressley, Kristin Stultz (2021). I Can't Give You Anything but Love, Baby: Dorothy Fields and Her Life in the American Musical Theater. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4930-5095-6.

- ^ "Samuel J. Buzzell, 87, Lawyer Represented Pop Composers". The New York Times. July 12, 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ "With the Music Men". Variety. Vol. 64, no. 11. November 4, 1921. p. 7. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "MILLS, BUZZELL'S SONS JOIN MUSIC CO. IN N.Y." Variety. Vol. 174, no. 1. March 16, 1949. p. 38.

- ^ "RICHMOND LETS BYGONES BE". The Billboard. November 4, 1950. p. 20. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "U&I President Heads New Mills Slate; Stanley Mills Prof. Mgr". Billboard. March 6, 1965. p. 4. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "Mills Will Merge With Belwin, Educational Pub". Billboard. October 4, 1969. p. 8.

- ^ "Belwin-Mills: Esquire Buying Firm" (PDF). Billboard. October 28, 1978. p. 103 – via American Radio History.[dead link]

- ^ "Gulf & Western Unit Sells Belwin-Mills Publishing". Wall Street Journal, Eastern edition. New York. March 25, 1985. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 397955995.

- ^ Shiver, Jube Jr. (August 9, 1990). "Thorn EMI Buys Filmtrax Catalogue for $115 Million Music: The huge collection of songs owned by the company includes 'Stormy Weather' and 'Against All Odds.'". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. p. 2. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 281273979. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Weaver, Jay (October 5, 1994). "Melodic merger print music divisions unite to form world's biggest publishing operation". Sun Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida, United States. pp. 1–. ProQuest 388726870.

- ^ "Alfred to purchase Warner Bros. Publications," American Music Teacher, April–May 2005

- ^ Sisario, Ben (November 11, 2011). "EMI Is Sold for $4.1 Billion in Combined Deals, Consolidating the Music Industry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Rood, George (February 26, 1965). "A Share of 'Star Dust' on Wall St.; Sale of Mills Music Makes It Possible to Invest in Songs". The New York Times. p. 37. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Hazeldine, Mike (January 20, 2002). "Rhythmakers". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.J377700.

- ^ Perlis, Vivian; Cleve, Libby Van (January 1, 2005). Composers Voices from Ives to Ellington: An Oral History of American Music (Unabridged ed.). Yale University Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-300-13837-5.

- ^ Tucker, Mark (1993). The Duke Ellington Reader (Illustrated reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509391-9.

- ^ Cohen, Harvey G. (Fall 2004). "The Marketing of Duke Ellington: Setting the Strategy for an African American Maestro". The Journal of African American History. 89 (4): 303–304. doi:10.2307/4134056. JSTOR 4134056. S2CID 145278913.

- ^ Prohaska, Jim (Spring 1997). "Irving Mills – Record Producer: The Master and Variety Record Labels". International Association of Jazz Record Collectors – via YUMPU.

References

[edit]- American song. The Complete Musical Theater Companion (2nd ed.) (Mills in Vol. 2 of 4), by Ken Bloom, Schirmer Books (1996); OCLC 11444314

- The Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music, Donald Clarke (ed.), Viking Press (1989); OCLC 59693135

- The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (3rd ed.) (Mills is in Vol. 5 of 8), Colin Larkin, Muze (1998); OCLC 39837948

- ASCAP Biographical Dictionary of Composers, Authors and Publishers (4th ed.), (Jacques Cattell Press (ed.), R. R. Bowker (1980); OCLC 7065938

- Music Printing and Publishing, Stanley John Sadie & Donald William Krummel, PhD (eds.), Macmillan Press, New Grove Handbooks in Music (1990), pg. 340; OCLC 21583943

External links

[edit]- Irving Mills 1894–1985 at Red Hot Jazz Archive by Mills' son Bob Mills

- Irving Mills at the Internet Broadway Database

- Irving Mills discography at Discogs

- Irving Mills at Find a Grave

- Irving Mills recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.