Getty Villa

The Outer Peristyle of the Villa | |

| |

| Established | 1954, reopened 2006 |

|---|---|

| Location | 17985 Pacific Coast Highway, Pacific Palisades, California |

| Coordinates | 34°02′42″N 118°33′54″W / 34.045°N 118.565°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | 44,000 Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities |

| Visitors | 509,000 (2021)[1] |

| Director | Timothy Potts |

| Public transit access | Note: Ticket must be punched by bus operator in order to enter the Getty Villa |

| Website | www.getty.edu/villa |

The Getty Villa is an educational center and art museum located at the easterly end of the Malibu coast in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, United States.[2] One of two campuses of the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Villa is dedicated to the study of the arts and cultures of ancient Greece, Rome, and Etruria. The collection has 44,000 Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities dating from 6,500 BC to 400 AD, including the Lansdowne Heracles and the Victorious Youth. The UCLA/Getty Master's Program in Archaeological and Ethnographic Conservation is housed on this campus.

History

[edit]

In 1954, oil tycoon J. Paul Getty opened a gallery adjacent to his home in Pacific Palisades.[3][4][5] Quickly running out of room, he built a second museum, the Getty Villa, on the property down the hill from the original gallery.[4][6] The villa design was inspired by the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum[6] and incorporated additional details from several other ancient sites.[7]

It was designed by architects Robert E. Langdon, Jr., and Ernest C. Wilson, Jr., in consultation with archeologist Norman Neuerburg.[8][9] It opened in 1974,[10] but was never visited by Getty, who died in 1976.[5] Following his death, the museum inherited $661 million[11] and began planning a much larger campus, the Getty Center, in nearby Brentwood. The museum overcame neighborhood opposition to its new campus plan by agreeing to limit the total size of the development on the Getty Center site.[12] To meet the museum's total space needs, the museum decided to split between the two locations with the Getty Villa housing the Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities.[12]

In 1993, the Getty Trust selected the Boston architects Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti to design a renovation of the Getty Villa and its campus.[12] In 1997, portions of the museum's collection of Greek, Roman and Etruscan antiquities were moved to the Getty Center for display, and the Getty Villa was closed for renovation.[13] The collection was restored during the renovation.[10]

In 2004, during the renovation, the museum and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), began holding summer institutes in Turkey, studying the conservation of Middle Eastern Art.[14]

Reopened on January 28, 2006, the Getty Villa shows Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities within Roman-inspired architecture and surrounded by Roman-style gardens.[15] The art is arranged by themes, e.g., Gods and Goddesses, Dionysos and the Theater, and Stories of the Trojan War.[15] The new architectural plan surrounding the Villa – which was conceived by Machado and Silvetti Associates (who were also responsible for the plans for the renovated museum) – is designed to simulate an archaeological dig. Architectural Record has praised their work on the Getty Villa as "a near miracle – a museum that elicits no smirks from the art world ... a masterful job ... crafting a sophisticated ensemble of buildings, plazas, and landscaping that finally provides a real home for a relic of another time and place."[16]

In 2016–2018 the collection was reinstalled in a chronological arrangement emphasizing art-historical themes.[17]

There has been controversy surrounding the Greek and Italian governments' claim that objects in the collection were looted and should be repatriated.[18] In 2006, the Getty returned or promised to return four looted objects to Greece: a stele (grave marker), a marble relief, a gold funerary wreath, and a marble statue.[19] In 2007, the Getty signed an agreement to return 40 looted items to Italy.[20][21]

The villa was host to leaders of the Western Hemisphere for dinner, held by President Joe Biden and First Lady Jill Biden in honor of the 9th Summit of the Americas on June 9, 2022, which was a first for the Villa.[22]

Facility and programs

[edit]

The Getty Villa hosts live performances in both its indoor auditorium and its outdoor theatre. Indoor play-readings included The Trojan Women, Aristophanes' The Frogs, and Euripides' Helen.[23] Indoor musical performances, which typically relate to art exhibits, included: Musica Angelica, De Organographia, and Songs from the Fifth Age: Sones de México in Concert.[24] The auditorium held a public reading of Homer's Iliad.[25]

Outdoor performances included Aristophanes' Peace, Aeschylus's Agamemnon, and Sophocles' Elektra.[26] The Getty Villa hosts visiting exhibitions beyond its own collections. For example, in March 2011 "In Search of Biblical Lands" was a photographic exhibition which included scenes of the Middle East dating back to the 1840s.[27]

The Getty Villa offers special educational programs for children. A special Family Forum gallery offers activities including decorating Greek vases and projecting shadows onto a screen that represents a Greek urn. The room also has polystyrene props from Greek and Roman culture for children to handle and use to cast shadows. The Getty Villa also offers children's guides to the other exhibits.[28][29]

The Getty Conservation Institute offers a Master's Program in Archaeological and Ethnographic Conservation in association with the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA. Classes and research are conducted in the museum wing of the ranch house. The program was the first of its kind in the United States.[30]

Campus

[edit]

The Villa self-identifies with Malibu as it is located just east of the city limits of Malibu in the city of Los Angeles in the community of Pacific Palisades.[13][31][32][33][34][35] The 64 acres (26 ha) museum complex sits on a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean, which is about 100 yards (91 m) from the entrance to the property. An outdoor 2,500-square-foot (230 m2) entry pavilion is also built into the hill near the 248-car, four story, South Parking garage at the southern end of the Outer Peristyle.[36] To the west of the Museum is a 450-seat outdoor Greek theater where evening performances are staged, named in honor of Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman.[36]

The theater faces the west side of the Villa and uses its entrance as a stage.[37] To the northwest of the theatre is a three-story, 15,500-square-foot (1,440 m2) building built into the hill that contains the museum store on the lower level, a cafe on the second level, and a private dining room on the top level.[38] North of the Villa is a 10,000 sq ft (930 m2) indoor 250-seat auditorium.[36] On the hill above the museum are Getty's original private ranch house and the museum wing that Getty added to his home in 1954. They are now used for curatorial offices, meeting rooms and as a library.[4] Although not open to the public, the campus includes J. Paul Getty's grave on the hill behind his ranch house.[39]

A 200-car North Parking Garage is behind the ranch complex. The 105,500-square-foot (9,800 m2) museum building is arranged in a square opening into the Inner Peristyle courtyard. The 2006 museum renovation added 58 windows facing the Inner Peristyle and a retractable skylight over the atrium.[16] It replaced the terrazzo floors in the galleries and added seismic protection with new steel reinforcing beams and new isolators in the bases of statues and display cases.[10] The museum has 48,000 sq ft (4,500 m2) of gallery space.[36][40]

Writing in 2008, the architectural critic Calum Storrie described the overall effect:

What the Getty Villa achieves, first by seclusion, then by control of access, and ultimately through the architecture, is a sense of detachment from its immediate environment.[41]

Gardens

[edit]There are four different gardens on the grounds of the Getty Villa, with plants native to the Mediterranean and known to have been cultivated by the ancient Romans.[42] The largest garden is the Outer Peristyle, an exact proportional replica of the one at the Villa dei Papiri. The garden is 308 by 105 feet (94 m × 32 m), with a 220 feet (67 m) long pool at the center. Traditional Roman landscaping designs are replicated with manicured bay laurel, boxwood, oleander, and viburnum shrubs. There are rows of date palms lining each of the long sides of the Outer Peristyle garden. Each corner features pomegranate trees surrounded by ornamental plants like acanthus, ivy, hellebore, lavender, and iris.[43]: 91 Copies of Roman bronzes excavated at the Villa dei Papiri and elsewhere are scattered throughout the garden.

Just west of the Outer Peristyle is the Herb Garden, where traditional herbs sourced from ancient Roman texts are cultivated along with a variety of fruit trees: pomegranate, fig, apricot, apple, citrus, and pear. The garden is surrounded by grapevines, and bounded by an olive grove planted on terraces above the garden.[43]: 100 The East Garden is small and secluded, surrounded by laurel and plane trees.[42] Its chief feature is an exact replica of the famous shell and mosaic fountain at the House of the Great Fountain in Pompeii, but there is also a circular fountain at the center of a basin filled with aquatic plants, around which the garden is oriented.[43]: 84–85

The fourth and final garden is the Inner Peristyle. Like the Outer Peristyle, a long, narrow, marble lined pool forms the centerpiece of the landscaping. Along each side are replicas of bronze female statues from the Villa dei Papiri, modelled to appear as if they are drawing water from the pool. In each corner of the garden is a replica white marble fountain, and there are several bronze copies of famous Greek sculptures like the Doryphoros and busts of Greek philosophers like Pythagoras and Democritus.[43]: 68–69

Collection

[edit]

The collection has 44,000 Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities dating from 6,500 BC to 400 AD,[44] of which approximately 1,400 are on view.[45]

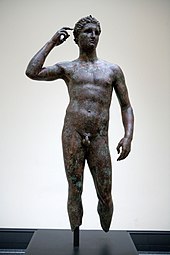

Among the outstanding items is Victorious Youth, one of few life-size Greek bronze statues to have survived to modern times.[6][46] The Lansdowne Heracles is a Hadrianic Roman sculpture in the manner of Lysippus.[47] The Villa has jewelry and coin collections[18] and an extensive 20,000 volume library of books covering art from these periods.[48]

The Villa displays the Getty kouros, which the museum lists as "Greek, about 530 B.C., or modern forgery" because scientific analysis is inconclusive as to whether the marble statue can be dated to Greek times.[37][49] If genuine, the Getty kouros is one of only twelve remaining intact lifesize kouroi.[50] The Marbury Hall Zeus is an 81 in (2.1 m) tall marble statue that was recovered from ruins at Tivoli near Rome.[51]

GettyGuide

[edit]Detailed information about the J. Paul Getty Museum's collection, audio tours, and maps of the Museum are provided on the "GettyGuide" app.[52]

Gallery

[edit]-

Outer Peristyle

-

Outer Peristyle – architectural detail

-

Inner Peristyle

-

Gallery within the Villa

-

The Lansdowne Herakles, part of the museum's collection

-

Ancient Roman glassware in the Getty Villa

-

Getty kouros, part of the museum's collection

-

Marbury Hall Zeus, King of the Gods, at the Getty Villa

-

Athena, Goddess of war, civilization, wisdom, strength, strategy, crafts, justice and skill

-

Roman-Egyptian Female Mummy Portrait

-

Roman gold medallion

-

Roman bronze statuette

-

Roman fresco fragment of a peacock

-

Roman head-shaped glass vessels

-

Statue of a Siren

-

Victorious Youth, part of the museum's collection

-

Etruscan amber pendant of a lion and a swan

-

Etruscan gold ring depicting a siren, sphinx, and hippocamp

-

Grave Stele of Pollis (480 BC)

See also

[edit]- Camillo Paderni described parts the Villa of the Papyri

Notes

[edit]- ^ Jose da Silva (March 22, 2022). "The top 100 most popular art museums in the world". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ "About the Museum (Getty Museum)". www.getty.edu. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Storrie at p. 186.

- ^ a b c "Architecture". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Bird, Cricket (June 10, 1976). "Getty Never Saw Fabulous Museum". Lewiston [Maine] Evening Journal. p. 10. Archived from the original on April 3, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c Ray, Derek (February 11, 2011). "The Getty Center and the Getty Villa". San Diego Reader. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Muchnic, Suzanne (December 6, 2019). "Stephen Garrett, architect and first director of Malibu's Getty Villa, dies". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ Myrna Oliver, Robert Langdon Jr., 86; Designed 1st Getty Museum, The Los Angeles Times, August 25, 2004

- ^ Grad student unearths architect's drawings for Getty exhibition Archived July 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, USC School of Architecture: School News, July 5, 2013

- ^ a b c Moltesen at p. 155.

- ^ Lenzner, Robert. The great Getty: the life and loves of J. Paul Getty, richest man in the world. New York: Crown Publishers, 1985. ISBN 0517562227

- ^ a b c Filler at 215.

- ^ a b Schultz, Patricia (2003). One thousand places to see before you die. Workman Publishing. p. 575. ISBN 978-0-7611-0484-1. Archived from the original on April 3, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "UCLA and Getty Museum Hold Summer Institute in Turkey". UCLA. September 23, 2004. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Moltesen at 157.

- ^ a b Pearson, Clifford A. (May 2006). "Machado and Silvetti creates an elaborate new setting that shows off the renovated Getty Villa without irony or apologies". Architectural Record. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ Potts, Timothy (April 2, 2018). "A New Vision for the Collection at the Getty Villa". The Getty Iris. J. Paul Getty Trust. Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Rogers, John (January 27, 2006). "Getty Museum reopening its much renovated villa". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Carassava, Anthee. Greeks Hail Getty Museum's Pledge to Return Treasures. Archived April 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine New York Times, December 12, 2006. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ Povoledo, Elisabetta. Italy and Getty Sign Pact on Artifacts. Archived April 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine New York Times, September 26, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- ^ Filler at pp. 221–23.

- ^ "Getty Villa Holds Dinner for the 9th Summit of the Americas".

- ^ "Villa Play–Reading Series". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "Concerts at the Villa". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "Public Reading of Homer's Iliad". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on September 7, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "Getty Villa Outdoor Theater Production". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "Calendar Picks and Clicks". Jewish Journal. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Family Forum". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Moltesen at p. 156.

- ^ "Getty Villa Press Kit" (PDF). Getty Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ E.g., Storrie at p. 186; Moltesen at p. 155.

- ^ Greenberg, Mark (2005). Guide to the Getty Villa. Getty Trust. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-89236-828-0.

- ^ "Visit the Getty". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Visit". The J. Paul Getty Trust. Archived from the original on July 29, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ Jaffee, Matthew (May 2007). "Posh Pacific Palisades". Sunset magazine. Archived from the original on November 24, 2007. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Fact Sheet" (PDF). Getty Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Filler at p. 221.

- ^ Filler at p. 220

- ^ Patricia Brooks; Jonathan Brooks (2006). Laid to Rest in California: A Guide to the Cemeteries and Grave Sites of the Rich and Famous. Globe Pequot. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-7627-4101-4. Retrieved March 8, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Map & Guide to the Getty Villa, Getty Trust, May 2010

- ^ Storrie at p. 187

- ^ a b "Gardens". www.getty.edu. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Guide to the Getty Villa. Getty Publications. 2005.

- ^ "Art (Visit the Getty Villa)". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Spier, Jeffrey (April 11, 2018). "What's New to Explore in the Reinstalled Getty Villa Galleries". The Getty Iris. J. Paul Getty Trust. Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Victorious Youth". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Lansdowne Herakles". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Research Libraries". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Statue of a Kouros". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ Robert Bianchi, "Saga of The Getty Kouros", Archaeology (May/June 1994).

- ^ "Marbury Hall Zeus". Getty Trust. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ GettyGuide® Archived 2023-09-02 at the Wayback Machine https://www.getty.edu/visit/app/

References

[edit]- Filler, Martin (2007). Makers of modern architecture. New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1-59017-227-8.

- Moltesen, Mette (January 2007). "The Reopened Getty Villa". American Journal of Archaeology. 111 (1). Boston University, Boston Massachusetts: The Archaeological Institute of America: 155–59. doi:10.3764/aja.111.1.155. ISSN 0002-9114.

- Storrie, Calum (2008). The Delirious Museum: A Journey from the Louvre to Las Vegas. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-509-8.

External links

[edit]- Getty.edu: official Getty Villa website

- Getty.edu: J. Paul Getty Trust website

- J Paul Getty Museum – GNIS data

- Vimeo.com: four-part documentary video about the Getty Villa and its Roman model, the Villa of the Papyri

- Flickr.com: photos tagged with "Getty Villa"

- J. Paul Getty Museum

- Art museums and galleries in Los Angeles

- Gardens in California

- Museums of ancient Rome in the United States

- Museums of ancient Greece in the United States

- Sculpture galleries in the United States

- Sculpture gardens, trails and parks in California

- Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles

- J. Paul Getty Trust

- Art museums and galleries established in 1954

- 1954 establishments in California

- Buildings and structures completed in 1974

- 1970s architecture in the United States

- Villas in the United States

- Replica buildings

- Landmarks in Los Angeles

- Culture of Los Angeles