Issun-bōshi

Issun-bōshi (一寸法師, "One-Sun Boy"; sometimes translated into English as "Little One-Inch" or "The Inch-High Samurai") is the subject of a fairy tale from Japan. This story can be found in the old Japanese illustrated book Otogizōshi. Similar central figures and themes are known elsewhere in the world, as in the tradition of Tom Thumb in English folklore.

Synopsis

[edit]

The general story is:

- A childless old couple prayed to the Sumiyoshi sanjin to be blessed with a child, and so they were able to have one. However, the child born was only one sun (around 3 cm or 1.2 in) in height and never grew taller. Thus, the child was named the "one-sun boy" or "Issun-bōshi".

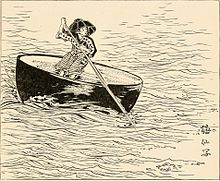

- One day, Issun-bōshi said he wanted to go the capital to become a warrior, so he embarked on his voyage with a bowl as a boat, a chopstick as a paddle, a needle as a sword, and a piece of straw as a scabbard.[1] In the capital, he found a splendid big house and found employment there. When a girl of that family went on a journey to visit a palace, an oni kidnapped the girl. As Issun-bōshi attempted to save the girl, the oni swallowed him up. Issun-bōshi used the needle to stab at the oni in the stomach, making the oni surrender, saying "it hurts, stop." The oni spat Issun-bōshi back out before fleeing to the mountains.

- Issun-bōshi picked up the magic hammer (Uchide no kozuchi) dropped by the oni and swung it to enlarge his body to a height of six shaku (about 182 cm or 6 ft) and married the girl. It is said that he was able to use that mallet to conjure food, treasures, and other things, and the family was able to prosper for generations.

However, the version of the story written in the Otogi-zōshi has a few differences:

- The old couple was disturbed by how Issun-bōshi never grew larger and thought he was some kind of monster. As a result, Issun-bōshi left their house.

- The place where Issun-bōshi lived in the capital was a chancellor's home.

- Issun-bōshi fell in love with the chancellor's daughter at first sight and wanted to make her his wife. However, he felt that with such a small body, she would not marry him, so he thought out a plan. He brought some of the rice grains offered to the family altar and put them in the girl's mouth, and then took an empty teabag and pretended to cry. When the chancellor saw this, Issun-bōshi lied and said that the girl stole some rice that he had been storing, and the chancellor believed this and attempted to kill his daughter. Issun-bōshi mediated between them and left the house together with the daughter.

- The boat that they rode on went with the wind and landed on an eerie island. There, they encountered an oni, and the oni swallowed Issun-bōshi whole. However, Issun-bōshi took advantage of his small body and went out of the oni's body through its eye. This repeated several times until the oni was frustrated and withdrew, leaving the magic hammer behind.

- The rumors of Issun-bōshi spread throughout society and he was summoned to the palace. The emperor took a liking to Issun-bōshi, and raised him to the rank of Chūnagon.

A version where Issun-bōshi strategized to marry a rich person's daughter is recorded in the Shinkoku Gudo Zuihitsu of the Edo period. Other documents record similar tales:[2]

- As a result of framing the daughter, Issun-bōshi was left in charge of her. Another theory is that by putting a suitor's food into's one's mouth, a person accepts that man's proposal.[2]

- The boy who became betrothed used the magic hammer to grow himself into a taller man and married the girl. Some versions may be missing a theme of making a strategy or plan with regards to the girl.[2]

- Some versions might only have the part about beating the oni and not about making such strategies or growing larger.[2]

There are also many differences in the tale depending on the region where it is told.[2]

Interpretation

[edit]It is unknown when the modern tale came about, but it is generally considered to have existed before the end of the Muromachi period. The theme of a "tiny child" is thought to have originated from Sukuna-hikona (written variously, including Sukunabikona) (meaning "small earth god": suku is "small", na is "the earth", hiko is "male god", and na is a suffix) of Japanese mythology.

Sukuna-hikona acts as a medium for the Dōjō Hōshi of the Nihon Ryōiki and Sugawara no Michizane of the Tenjin Engi (天神縁起) and is connected to the Kootoko no Sōshi (小男の草子, "Book about the Small Man") from the Middle Ages and the otogi-zōshi of the modern ages.

It has been pointed out that just like how the nation-creator god Sukuna-hikona appeared near water, the main character of the old tale "Chiisa-ko" (small child) is in some way related to the world of water and is related to the existence of a faith in a water god. For an old couple not to have any children is an abnormality within the community and for such abnormal persons give birth in an abnormal way such as by praying to a god and giving birth from the shin to a person in the form of a pond snail, as one would find in the tale Tanishi Chōja, is the normal course for tales about heroes and children of god.[3]

As the Issun Bōshi of the otogi-zōshi became famous, people of various different lands started calling their folktales and legends about little people "Issun Bōshi" as well.

In the Edo period, "Issun Bōshi" was used as a pejorative term against short people, and in kyōka books about yōkai such as the Kyōka Hyakki Yakyō (狂歌百鬼夜狂) and the Kyōka Hyaku Monogatari, Issun Bōshi were written about to be a type of yōkai.[4]

Also, Issun Bōshi's location of residence, the village of Naniwa (國難波) of Tsu Province, is said to be near the area between present-day Nanba (難波) and Mittera (三津寺). Also, in the Otogizōshi, there is the statement "Perhaps my heart longs to leave this shore of Nanba I've grown accustomed to living in and hurry to the capital" (すみなれし難波の浦をたちいでて都へいそぐわが心かな, suminareshi Nanba no ura wo tachiidete miyako he isogu wa ga kokoro ka na), so this "shore of Nanba" that was the point of departure for heading to the capital on a bowl is nowadays said to be the Dōtonbori river canal.[5]

Folkloristics

[edit]Just like how Ōkuninushi no Mikoto (or Ōnamuchi, meaning "big earth": Ō means "big", na means "the earth", and muchi is an honorific) helped Sukuna-hikona create the nation, it often happens that a little person and giant would appear as a pair and would each separately have the different aspects for being a hero: power and knowledge.[3]

The giant would be lacking in knowledge and would thus fall and be reduced to being an oni or laughingstock, whereas the little person, on the other hand, would make use of cunning and as a result eventually become a fully formed adult and return home to live happily ever after. A tiny child would, of course, be let off the hook for malicious deeds.[3]

In the Tawara Yakushi, old tale about a cunning lad, a wicked and cunning child who displays not a single bit of a hero's sense of justice appears as the main character of this story, and in it he thoroughly trounces and kills his rich employer using a method similar to Issun Bōshi's but of course in a wicked manner. The child lies and tricks his master one time after another until finally he pushes his master over a levee and kills him as a result and after that forces the master's wife to marry him. Thus the story closes with "and so he became married to the unwilling former master's wife. The end" (iyagaru okami-sama to muriyari fuufu ni natta do sa. dotto harai), a comedic tone full of parody and black humor.[3]

This boy who obtains wealth and a woman by means of lies and slaughter is basically the flip side appearance of the Issun Bōshi who obtained an oni's treasure and a woman by means of wisdom and is none other than the descendant of the aforementioned "Chiisa-ko" god.[3]

The cruelty of the boy in the Tawara Yakushi is directed at innocent others. In fact, he would even go so far as to deceive and take advantage of the weak, such as the blind or beggars with eye illnesses, so that they would take the blame and die in his place.

This slaughter of others reveals a dark side to the village where the killing of others can be considered a form of compensation. As the tale humorously makes fun of a wicked usage of wisdom, it makes a show of how wisdom has a destructiveness that can surpass society's sense of order as well as the complexities of the village's society. It is said that wisdom is filled with dangerous power that can turn righteousness and purity meaningless and laugh away at the stability and orderliness of society important for maintaining political power. Inomata Tokiwa, a lecturer at Kyoritsu Women's Junior College, analyzes this saying that it tells of how even though Sukuna-hikona is a god who created the nation as well and the creator god of chemical technology such as drugs (medicine) and alcohol, "wisdom" by itself is not a representation of societal orderliness.[3]

Similar tales

[edit]Stories in which "Chiisa-ko" plays a role include the all-national Issun Bōshi, the Suneko Tanpoko, the Akuto Tarō (akuto means "heel"), Mamesuke (meaning "thumb"), Yubi Tarō ("yubi", meaning "finger", refers to the place of birth), Mameichi (referring to the thumb), Gobu Tarō (or Jirō) ("Gobu" is literally "five bu" but also a general term for small things), Sanmontake ("mon" is a counter for coins, so it means "three coins height" or the height of a stack of three coins), Issun Kotarō, Tanishi (meaning "pond snail"), Katamutsuri (meaning "snail"), Kaeru (meaning "frog"), the Koropokkurukamui of the Ainu people, the Kijimuna, the Kenmun, among others, and tales of those born abnormally small such as Momotarō, Uriko-hime to Amanojaku ("Princess Uriko and the Amanojaku"), and Kaguya-hime are also related. There is a lot of variation with it comes to whether or not it includes beating an oni, scheming to marry someone, and the usage of a magical tool. Stories that start with birth from the shin or finger or small animal among other possibilities and develop into making a scheme to get someone to agree to marriage are old, but newer than the Issun Bōshi tale in the otogi-zōshi. It has left is mark popularizing old tales in the Chūgoku and Shikoku regions.[3]

Nursery tales

[edit]- The Meiji Period children's book Nihon Mukashibanashi (日本昔噺, "Old Tales of Japan") by Iwaya Sazanami first published in 1896 or Meiji 29 has within one of its 24 volumes popularly established the Sazanami-type Issun Bōshi. Over 20 editions of this book were printed in the approximately ten years between then and 1907 or Meiji 40, and they were widely read until the end of the Taishō period. The story currently published in children's book mostly follows this Sazanami-type Issun Bōshi tale. It removes any wickedness that was in the original and turns Issun Bōshi into a more loveable figure.[6]

- Among picture books, the book Issun Bōshi written by Ishii Momoko and illustrated by Akino Fuku published in 1965 by Fukuinkan Shoten Fukuinkan Shoten is of particular note.[6]

- Hop-o'-My-Thumb as told by Charles Perrault was introduced to Japan under the title Shōsetsu Issun Bōshi (Novelized Issun Bōshi) as it was published in the magazine Shōkokumin in 1896 (Meiji 29).[7]

Songs

[edit]- In 1905 (Meiji 38), Jinjō Shōgaku Shōka ("The Common Songs for Elementary Schoolers") included one titled "Issun Bōshi" by Iwaya Sazanami, and it continues to be sung by children today.[6]

Other versions

[edit]There are many other versions of the story Issun-bōshi, but there are some that seem to take on a completely different story of their own, and have stayed that way since their new retellings. These versions include the story of Mamasuke, the adult version of Issun-boshi, and the modernized version that are seen worldwide today.

Mamesuke

[edit]The Mamesuke version of Issun-bōshi is essentially the same, except for a few key defining factors. Rather than being born from his mother's womb, Issun-boshi was born from the swelling of his mother's thumb. He was also called Mamesuke, which means bean boy instead of Issun-bōshi, even though the story is still called Issun-bōshi. He does still set out on his own at some point, but instead of being armed with a sewing needle, bowl, and chopsticks, all he has is a bag of flour. He eventually finds his way to a very wealthy wine merchant who has three daughters. Mamesuke wishes to marry the middle daughter, so he begins to work for the merchant and live there. One night, Mamesuke takes the flour he has and wipes it on the daughter's mouth, then throws the rest into the river. In the morning, he pretends to cry because his flour is gone, so the family investigates as to where it went when they discovered the flour on the middle daughter. She gets upset because she had nothing to do with the flour, but her family turns her over to Mamesuke as payment. He then begins to lead the girl home to his parents, while along the way the girl is so angry that she tries to find ways to kill him, but she could not find one. When Mamesuke returned home, his parents were so delighted with the girl that they set up a hot bath for him. Mamesuke got in and called for his bride to help him wash, but she came in with a broom instead and stirred up the water in an attempt to drown him. Mamesuke's body suddenly burst open, and out stepped a full sized man. The bride and parents were surprised yet extremely happy, so Mamesuke and his bride lived happily with his parents.[8]

The love affair of Issun-boshi

[edit]In other media, Issun-boshi makes an appearance as the character Issun, and is depicted as a pervert of sorts. This depiction relates back to the adult version of Issun-boshi, also known as The Love Affair of Issun-bōshi. The beginning of the story is essentially the same until Issun-boshi reaches the capital. When he comes upon the home of a wealthy lord, Issun-bōshi convinces him that he can do anything, so he should let him work for him. The lord tells him to do a dance for him, and he was so amused by Issun-bōshi's dance that he decides to make him a playmate for his daughter. For a while, Issun-bōshi just listens to the daughter talk during the day, then he would tell her stories that she would fall asleep to at night. Issun-bōshi fell in love with her, and eventually she fell in love with him. One day the princess decides to head to a temple to go pray, and brings Issun-bōshi along with her. They are attacked by ogres along the way, and Issun-bōshi saves the princess, who then discovers the lucky mallet and makes Issun-bōshi normal sized. It was thought they would live happily ever after, but the couple would get into horrible fights, especially about how Issun-bōshi could not pleasure the princess like he used to. In his anger, Issun-bōshi used the lucky mallet to shrink the princess down, who in turn snatched the hammer from him and shrank him down. They went back and forth shrinking one another to the point where all that was left was the lucky mallet.[9]

Modernized Issun-boshi

[edit]The modernized version of Issun-bōshi is very similar to the original, except there are different happenings that make it more universally acceptable. Rather than setting out on his own, Issun-bōshi's parents send him off to learn about the world on his own. He still travels to the capital and ends up in the home of a wealthy lord, but rather than his daughter disliking him, she immediately fell in love with him, as well as the other residents of the lord's home. Issun-bōshi and the girl still get attacked by ogres and obtain the lucky mallet, which is then used to make him normal sized. He grows into a fine young samurai, but it was never made clear where Issun-bōshi went from there. This abrupt ending is set up so that the audience can make their own guesses about what happened to Issun-bōshi.[10]

In the 8th Season of Yami Shibai, Episode 07, Issub-bōshi is described as a creature which, when offended or provoked, can go inside a human body and as punishment turn it into a grotesque one, with large lumps sprouting randomly. He can also order the affected human to do evil things such as killing a person or in its words "punishing" them. The affected human will not be able to disobey said order and will forever succumb to Issub-bōshi's curse.

Themes

[edit]The story of Issun-bōshi follows three common themes that appear in almost every Japanese folk tale. The first theme is that those who are devout and pray often are blessed with a child. Issun-bōshi's parents prayed day after day until a child was born unto them. This theme also appears in the Japanese folk tale "Momotarō". The second theme is that the accomplishments of these children are so extraordinary that they achieve almost every task that the audience wishes them to accomplish. Issun-bōshi gets the love of his life, attains a normal size, and becomes a well known samurai. The third theme is that said child grows up to have a good marriage and carries a special family name. In most versions, Issun-bōshi marries some sort of official's daughter and becomes a very famous samurai.[11]

Religious differences

[edit]In each of the different retellings of Issun-bōshi, there are different gods, goddesses, and deities that are mentioned in each, which are due to the differing regional religions at the time. In the modernized version as well as the adult versions of Issun-boshi, the princess he meets goes to pray to the Goddess Kannon. In Japan, Kannon is known as the goddess of child rearing and mercy, but the goddess has Buddhist origins. Buddhism originated in India but it grew across Asia and eventually settled in Japan as a base for Buddhism around the time Issun-bōshi became popular, which could potentially explain its influence in these versions of Issun-bōshi.[12] In the modernized version of Issun-bōshi, his parents go pray to what they call "Sumiyoshi sanjin", which is actually the name of a temple in Osaka, Japan. This temple is used for Shinto religious purposes, so the story of Issun-bōshi actually embodies multiple religions.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 岩井宏實 (2004). 妖怪と絵馬と七福神. プレイブックスインテリジェンス. 青春出版社. pp. 50頁. ISBN 978-4-413-04081-5.

- ^ a b c d e 常光徹 (1987). "一寸法師". In 野村純一他編 (ed.). 昔話・伝説小事典year=1987. みずうみ書房. pp. 37頁. ISBN 978-4-8380-3108-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g 猪股ときわ (1992). "小人伝説". In 吉成勇編 (ed.). 日本「神話・伝説」総覧. 歴史読本特別増刊・事典シリーズ. 新人物往来社. pp. 254–255頁. ISBN 978-4-4040-2011-6.

- ^ 京極夏彦・多田克己編著 (2008). 妖怪画本 狂歌百物語. 国書刊行会. pp. 299頁. ISBN 978-4-3360-5055-7.

- ^ このため、道頓堀商店街では2002年に一寸法師おわん船レースを開催したほか、法善寺横丁にある浮世小路に一寸法師を大明神として祀る神社が2004年に建立された。

- ^ a b c 土橋悦子. "いっすんぼうし". 昔話・伝説小事典. pp. 38頁.

- ^ 土橋悦子. "おやゆびこぞう". 昔話・伝説小事典. pp. 65頁.

- ^ Sado, Niigata (1948). The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale. Tokyo. pp. 11–13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kurahashi, Yumiko (2008). "Two Tales from Cruel Fairy Tales for Adults". Marvels and Tales. 22 (1): 171–. doi:10.1353/mat.2008.a247507. S2CID 152588397. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Seki, Keigo (1963). Folktales of Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 90–92.

- ^ Kawamori, Hiroshi (2003). "Folktale Research after Yanagita". Asian Folklore Studies. 62: 237–256. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Schumacher, Mark. "Kannon Bodhisattva (Bosatsu) - Goddess of Mercy, One Who Hears Prayers of the World, Japanese Buddhism Art History". Mark Schumacher. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Ward, Mindy. "Sumiyoshi Taisha - Japanese Religions". Japanese Religions. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

External links

[edit]- いっすんぼうし animated depiction with English closed captioning