Iron-based superconductor

Iron-based superconductors (FeSC) are iron-containing chemical compounds whose superconducting properties were discovered in 2006.[2][3] In 2008, led by recently discovered iron pnictide compounds (originally known as oxypnictides), they were in the first stages of experimentation and implementation.[4] (Previously most high-temperature superconductors were cuprates and being based on layers of copper and oxygen sandwiched between other substances (La, Ba, Hg)).

This new type of superconductors is based instead on conducting layers of iron and a pnictide (chemical elements in group 15 of the periodic table, here typically arsenic (As) and phosphorus (P)) and seems to show promise as the next generation of high temperature superconductors.[5]

Much of the interest is because the new compounds are very different from the cuprates and may help lead to a theory of non-BCS-theory superconductivity.

More recently these have been called the ferropnictides. The first ones found belong to the group of oxypnictides. Some of the compounds have been known since 1995,[6] and their semiconductive properties have been known and patented since 2006.[7] It has also been found that some iron chalcogens superconduct.[8] The undoped β-FeSe is the simplest iron-based superconductor but with the diverse properties.[9] It has a critical temperature (Tc) of 8 K at normal pressure, and 36.7 K under high pressure[10] and by means of intercalation. The combination of both intercalation and higher pressure results in re-emerging superconductivity at Tc of up to 48 K (see,[9][11] and references therein). A subset of iron-based superconductors with properties similar to the oxypnictides, known as the 122 iron arsenides, attracted attention in 2008 due to their relative ease of synthesis.

| Oxypnictide | Tc (K) |

|---|---|

| LaO0.89F0.11FeAs | 26[12] |

| LaO0.9F0.2FeAs | 28.5[13] |

| CeFeAsO0.84F0.16 | 41[12] |

| SmFeAsO0.9F0.1 | 43[12][14] |

| La0.5Y0.5FeAsO0.6 | 43.1[15] |

| NdFeAsO0.89F0.11 | 52[12] |

| PrFeAsO0.89F0.11 | 52[16] |

| ErFeAsO1−y | 45[17] |

| Al-32522 (CaAlOFeAs) | 30(As), 16.6 (P)[18] |

| Al-42622 (CaAlOFeAs) | 28.3(As), 17.2 (P)[19] |

| GdFeAsO0.85 | 53.5[20] |

| BaFe1.8Co0.2As2 | 25.3[21] |

| SmFeAsO~0.85 | 55[22] |

| Non-oxypnictide | Tc (K) |

|---|---|

| Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 | 38[23] |

| Ca0.6Na0.4Fe2As2 | 26[24] |

| CaFe0.9Co0.1AsF | 22[25] |

| Sr0.5Sm0.5FeAsF | 56[26] |

| LiFeAs | 18[27][28][29] |

| NaFeAs | 9–25[30][31] |

| FeSe | <27[32][33] |

| LaFeSiH | 10[34] |

The oxypnictides such as LaOFeAs are often referred to as the '1111' pnictides.

The crystalline material, known chemically as LaOFeAs, stacks iron and arsenic layers, where the electrons flow, between planes of lanthanum and oxygen. Replacing up to 11 percent of the oxygen with fluorine improved the compound – it became superconductive at 26 kelvin, the team reports in the March 19, 2008 Journal of the American Chemical Society. Subsequent research from other groups suggests that replacing the lanthanum in LaOFeAs with other rare earth elements such as cerium, samarium, neodymium and praseodymium leads to superconductors that work at 52 kelvin.[5]

Iron pnictide superconductors crystallize into the [FeAs] layered structure alternating with spacer or charge reservoir block.[12] The compounds can thus be classified into "1111" system RFeAsO (R: the rare earth element) including LaFeAsO,[3] SmFeAsO,[14] PrFeAsO,[22] etc.; "122" type BaFe2As2,[23] SrFe2As2[35] or CaFe2As2;[24] "111" type LiFeAs,[27][28][29] NaFeAs,[30][31][36] and LiFeP.[37] Doping or applied pressure will transform the compounds into superconductors.[12][38][39]

Compounds such as Sr2ScFePO3 discovered in 2009 are referred to as the '42622' family, as FePSr2ScO3.[40] Noteworthy is the synthesis of (Ca4Al2O6−y)(Fe2Pn2) (or Al-42622(Pn); Pn = As and P) using high-pressure synthesis technique. Al-42622(Pn) exhibit superconductivity for both Pn = As and P with the transition temperatures of 28.3 K and 17.1 K, respectively. The a-lattice parameters of Al-42622(Pn) (a = 3.713 Å and 3.692 Å for Pn = As and P, respectively) are smallest among the iron-pnictide superconductors. Correspondingly, Al-42622(As) has the smallest As–Fe–As bond angle (102.1°) and the largest As distance from the Fe planes (1.5 Å).[19] High-pressure technique also yields (Ca3Al2O5−y)(Fe2Pn2) (Pn = As and P), the first reported iron-based superconductors with the perovskite-based '32522' structure. The transition temperature (Tc) is 30.2 K for Pn = As and 16.6 K for Pn = P. The emergence of superconductivity is ascribed to the small tetragonal a-axis lattice constant of these materials. From these results, an empirical relationship was established between the a-axis lattice constant and Tc in iron-based superconductors.[18]

In 2009, it was shown that undoped iron pnictides had a magnetic quantum critical point deriving from competition between electronic localization and itinerancy.[41]

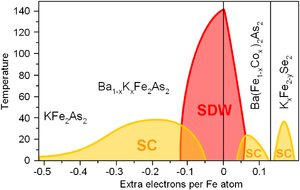

Phase diagrams

[edit]Similarly to superconducting cuprates, the properties of iron based superconductors change dramatically with doping. Parent compounds of FeSC are usually metals (unlike the cuprates) but, similarly to cuprates, are ordered antiferromagnetically that often termed as a spin-density wave (SDW). The superconductivity (SC) emerges upon either hole or electron doping. In general, the phase diagram is similar to the cuprates.[42]

Superconductivity at high temperature

[edit]

Superconducting transition temperatures are listed in the tables (some at high pressure). BaFe1.8Co0.2As2 is predicted to have an upper critical field of 43 tesla from the measured coherence length of 2.8 nm.[21]

In 2011, Japanese scientists made a discovery which increased a metal compound's superconductivity by immersing iron-based compounds in hot alcoholic beverages such as red wine.[48][49] Earlier reports indicated that excess Fe is the cause of the bicollinear antiferromagnetic order and is not in favor of superconductivity. Further investigation revealed that weak acid has the ability to deintercalate the excess Fe from the interlayer sites. Therefore, weak acid annealing suppresses the antiferromagnetic correlation by deintercalating the excess Fe and, hence superconductivity is achieved.[50][51]

There is an empirical correlation of the transition temperature with electronic band structure: the Tc maximum is observed when some of the Fermi surface stays in proximity to Lifshitz topological transition.[42] Similar correlation has been later reported for high-Tc cuprates that indicates possible similarity of the superconductivity mechanisms in these two families of high temperature superconductors.[52]

Thin films

[edit]The critical temperature is increased further in thin-films of iron chalcogenides on suitable substrates. In 2015, a Tc of around 105–111 K was observed in thin films of iron selenide grown on strontium titanate.[53]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hosono, H.; Tanabe, K.; Takayama-Muromachi, E.; Kageyama, H.; Yamanaka, S.; Kumakura, H.; Nohara, M.; Hiramatsu, H.; Fujitsu, S. (2015). "Exploration of new superconductors and functional materials, and fabrication of superconducting tapes and wires of iron pnictides". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 16 (3): 033503. arXiv:1505.02240. Bibcode:2015STAdM..16c3503H. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/16/3/033503. PMC 5099821. PMID 27877784.

- ^ Kamihara, Yoichi; Hiramatsu, Hidenori; Hirano, Masahiro; Kawamura, Ryuto; Yanagi, Hiroshi; Kamiya, Toshio; Hosono, Hideo (2006). "Iron-Based Layered Superconductor: LaOFeP". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (31): 10012–10013. doi:10.1021/ja063355c. PMID 16881620.

- ^ a b Kamihara, Yoichi; Watanabe, Takumi; Hirano, Masahiro; Hosono, Hideo (2008). "Iron-Based Layered Superconductor La[O1−xFx]FeAs (x = 0.05–0.12) with Tc = 26 K". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (11): 3296–3297. doi:10.1021/ja800073m. PMID 18293989.

- ^ Ozawa, T C; Kauzlarich, S M (2008). "Chemistry of layered d-metal pnictide oxides and their potential as candidates for new superconductors". Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 9 (3): 033003. arXiv:0808.1158. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9c3003O. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/3/033003. PMC 5099654. PMID 27877997.

- ^ a b "Iron Exposed as High-Temperature Superconductor". Scientific American. June 2008

- ^ Zimmer, Barbara I.; Jeitschko, Wolfgang; Albering, Jörg H.; Glaum, Robert; Reehuis, Manfred (1995). "The rate earth transition metal phosphide oxides LnFePO, LnRuPO and LnCoPO with ZrCuSiAs type structure". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 229 (2): 238–242. doi:10.1016/0925-8388(95)01672-4.

- ^ Hosono, H. et al. (2006) Magnetic semiconductor material European Patent Application EP1868215

- ^ Johannes, Michelle (2008). "The iron age of superconductivity". Physics. 1: 28. Bibcode:2008PhyOJ...1...28J. doi:10.1103/Physics.1.28.

- ^ a b Yu. V. Pustovit; A. A. Kordyuk (2016). "Metamorphoses of electronic structure of FeSe-based superconductors (Review article)". Low Temp. Phys. 42 (11): 995–1007. arXiv:1608.07751. Bibcode:2016LTP....42..995P. doi:10.1063/1.4969896. S2CID 119184569.

- ^ Medvedev, S.; McQueen, T. M.; Troyan, I. A.; Palasyuk, T.; Eremets, M. I.; Cava, R. J.; Naghavi, S.; Casper, F.; Ksenofontov, V.; Wortmann, G.; Felser, C. (2009). "Electronic and Magnetic Phase Diagram of β-Fe1.01Se with superconductivity at 36.7 K under pressure". Nature Materials. 8 (8): 630–633. arXiv:0903.2143. Bibcode:2009NatMa...8..630M. doi:10.1038/nmat2491. PMID 19525948. S2CID 117714394.

- ^ Sun, Liling; Chen, Xiao-Jia; Guo, Jing; Gao, Peiwen; Huang, Qing-Zhen; Wang, Hangdong; Fang, Minghu; Chen, Xiaolong; Chen, Genfu; Wu, Qi; Zhang, Chao; Gu, Dachun; Dong, Xiaoli; Wang, Lin; Yang, Ke; Li, Aiguo; Dai, Xi; Mao, Ho-kwang; Zhao, Zhongxian (2012). "Re-emerging superconductivity at 48 kelvin in iron chalcogenides". Nature. 483 (7387): 67–69. arXiv:1110.2600. Bibcode:2012Natur.483...67S. doi:10.1038/nature10813. PMID 22367543.

- ^ a b c d e f Ishida, Kenji; Nakai, Yusuke; Hosono, Hideo (2009). "To What Extent Iron-Pnictide New Superconductors Have Been Clarified: A Progress Report". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 78 (6): 062001. arXiv:0906.2045. Bibcode:2009JPSJ...78f2001I. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.78.062001. S2CID 119295430.

- ^ Prakash, J.; Singh, S. J.; Samal, S. L.; Patnaik, S.; Ganguli, A. K. (2008). "Potassium fluoride doped LaOFeAs multi-band superconductor: Evidence of extremely high upper critical field". EPL. 84 (5): 57003. Bibcode:2008EL.....8457003P. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/84/57003. S2CID 119254951.

- ^ a b Chen, X. H.; Wu, T.; Wu, G.; Liu, R. H.; Chen, H.; Fang, D. F. (2008). "Superconductivity at 43 K in SmFeAsO1–xFx". Nature. 453 (7196): 761–762. arXiv:0803.3603. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..761C. doi:10.1038/nature07045. PMID 18500328. S2CID 115842939.

- ^ Shirage, Parasharam M.; Miyazawa, Kiichi; Kito, Hijiri; Eisaki, Hiroshi; Iyo, Akira (2008). "Superconductivity at 43 K at ambient pressure in the iron-based layered compound La1−xYxFeAsOy". Physical Review B. 78 (17): 172503. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..78q2503S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.172503.

- ^ Ren, Z. A.; Yang, J.; Lu, W.; Yi, W.; Che, G. C.; Dong, X. L.; Sun, L. L.; Zhao, Z. X. (2008). "Superconductivity at 52 K in iron based F doped layered quaternary compound Pr[O1−xFx]FeAs". Materials Research Innovations. 12 (3): 105–106. arXiv:0803.4283. Bibcode:2008MatRI..12..105R. doi:10.1179/143307508X333686. S2CID 55488705.

- ^ Shirage, Parasharam M.; Miyazawa, Kiichi; Kihou, Kunihiro; Lee, Chul-Ho; Kito, Hijiri; Tokiwa, Kazuyasu; Tanaka, Yasumoto; Eisaki, Hiroshi; Iyo, Akira (2010). "Synthesis of ErFeAsO-based superconductors by the hydrogen doping method". EPL. 92 (5): 57011. arXiv:1011.5022. Bibcode:2010EL.....9257011S. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/92/57011. S2CID 118303767.

- ^ a b Shirage, Parasharam M.; Kihou, Kunihiro; Lee, Chul-Ho; Kito, Hijiri; Eisaki, Hiroshi; Iyo, Akira (2011). "Emergence of Superconductivity in "32522" Structure of (Ca3Al2O5−y)(Fe2Pn2) (Pn = As and P)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 133 (25): 9630–3. doi:10.1021/ja110729m. PMID 21627302.

- ^ a b Shirage, Parasharam M.; Kihou, Kunihiro; Lee, Chul-Ho; Kito, Hijiri; Eisaki, Hiroshi; Iyo, Akira (2010). "Superconductivity at 28.3 and 17.1 K in (Ca4Al2O6−y)(Fe2Pn2) (Pn=As and P)". Applied Physics Letters. 97 (17): 172506. arXiv:1008.2586. Bibcode:2010ApPhL..97q2506S. doi:10.1063/1.3508957. S2CID 117899145.

- ^ Yang, Jie; Li, Zheng-Cai; Lu, Wei; Yi, Wei; Shen, Xiao-Li; Ren, Zhi-An; Che, Guang-Can; Dong, Xiao-Li; Sun, Li-Ling; Zhou, Fang; Zhao, Zhong-Xian (2008). "Superconductivity at 53.5 K in GdFeAsO1−δ". Superconductor Science and Technology. 21 (8): 082001. arXiv:0804.3727. Bibcode:2008SuScT..21h2001Y. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/21/8/082001. S2CID 121990600.

- ^ a b Yin, Yi; Zech, M.; Williams, T. L.; Wang, X. F.; Wu, G.; Chen, X. H.; Hoffman, J. E. (2009). "Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy and Vortex Imaging in the Iron Pnictide Superconductor BaFe1.8Co0.2As2". Physical Review Letters. 102 (9): 97002. arXiv:0810.1048. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102i7002Y. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.097002. PMID 19392555. S2CID 16583932.

- ^ a b Ren, Zhi-An; Che, Guang-Can; Dong, Xiao-Li; Yang, Jie; Lu, Wei; Yi, Wei; Shen, Xiao-Li; Li, Zheng-Cai; Sun, Li-Ling; Zhou, Fang; Zhao, Zhong-Xian (2008). "Superconductivity and phase diagram in iron-based arsenic-oxides ReFeAsO1−δ (Re = rare-earth metal) without fluorine doping". EPL. 83 (1): 17002. arXiv:0804.2582. Bibcode:2008EL.....8317002R. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/83/17002. S2CID 96240327.

- ^ a b Rotter, Marianne; Tegel, Marcus; Johrendt, Dirk (2008). "Superconductivity at 38 K in the Iron Arsenide (Ba1−xKx)Fe2As2". Physical Review Letters. 101 (10): 107006. arXiv:0805.4630. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101j7006R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.107006. PMID 18851249. S2CID 25876149.

- ^ a b Shirage, Parasharam Maruti; Miyazawa, Kiichi; Kito, Hijiri; Eisaki, Hiroshi; Iyo, Akira (2008). "Superconductivity at 26 K in (Ca1−xNax)Fe2As2". Applied Physics Express. 1 (8): 081702. Bibcode:2008APExp...1h1702M. doi:10.1143/APEX.1.081702. S2CID 94498268.

- ^ Satoru Matsuishi; Yasunori Inoue; Takatoshi Nomura; Hiroshi Yanagi; Masahiro Hirano; Hideo Hosono (2008). "Superconductivity Induced by Co-Doping in Quaternary Fluoroarsenide CaFeAsF". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (44): 14428–14429. doi:10.1021/ja806357j. PMID 18842039.

- ^ Wu, G; Xie, Y L; Chen, H; Zhong, M; Liu, R H; Shi, B C; Li, Q J; Wang, X F; Wu, T; Yan, Y J; Ying, J J; Chen, X H (2009). "Superconductivity at 56 K in samarium-doped SrFeAsF". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 21 (14): 142203. arXiv:0811.0761. Bibcode:2009JPCM...21n2203W. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/21/14/142203. PMID 21825317. S2CID 41728130.

- ^ a b Wang, X.C.; Liu, Q.Q.; Lv, Y.X.; Gao, W.B.; Yang, L.X.; Yu, R.C.; Li, F.Y.; Jin, C.Q. (2008). "The superconductivity at 18 K in LiFeAs system". Solid State Communications. 148 (11–12): 538–540. arXiv:0806.4688. Bibcode:2008SSCom.148..538W. doi:10.1016/j.ssc.2008.09.057. S2CID 55247836.

- ^ a b Pitcher, Michael J.; Parker, Dinah R.; Adamson, Paul; Herkelrath, Sebastian J. C.; Boothroyd, Andrew T.; Ibberson, Richard M.; Brunelli, Michela; Clarke, Simon J. (2008). "Structure and superconductivity of LiFeAs". Chemical Communications (45): 5918–20. arXiv:0807.2228. doi:10.1039/b813153h. PMID 19030538. S2CID 3258249.

- ^ a b Tapp, Joshua H.; Tang, Zhongjia; Lv, Bing; Sasmal, Kalyan; Lorenz, Bernd; Chu, Paul C. W.; Guloy, Arnold M. (2008). "LiFeAs: An intrinsic FeAs-based superconductor with Tc=18 K". Physical Review B. 78 (6): 060505. arXiv:0807.2274. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..78f0505T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.060505. S2CID 118379012.

- ^ a b Chu, C.W.; Chen, F.; Gooch, M.; Guloy, A.M.; Lorenz, B.; Lv, B.; Sasmal, K.; Tang, Z.J.; Tapp, J.H.; Xue, Y.Y. (2009). "The synthesis and characterization of LiFeAs and NaFeAs". Physica C: Superconductivity. 469 (9–12): 326–331. arXiv:0902.0806. Bibcode:2009PhyC..469..326C. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2009.03.016. S2CID 118531206.

- ^ a b Parker, Dinah R.; Pitcher, Michael J.; Clarke, Simon J. (2008). "Structure and superconductivity of the layered iron arsenide NaFeAs". Chemical Communications. 2189 (16): 2189–91. arXiv:0810.3214. doi:10.1039/B818911K. PMID 19360189. S2CID 45189652.

- ^ Fong-Chi Hsu, et al. (2008). "Superconductivity in the PbO-type structure α-FeSe". PNAS. 105 (38): 14262–14264. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10514262H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807325105. PMC 2531064. PMID 18776050.

- ^ Mizuguchi, Yoshikazu; Tomioka, Fumiaki; Tsuda, Shunsuke; Yamaguchi, Takahide; Takano, Yoshihiko (2008). "Superconductivity at 27 K in tetragonal FeSe under high pressure". Appl. Phys. Lett. 93 (15): 152505. arXiv:0807.4315. Bibcode:2008ApPhL..93o2505M. doi:10.1063/1.3000616. S2CID 119218961.

- ^ Bernardini, F.; Garbarino, G.; Sulpice, A.; Núñez-Regueiro, M.; Gaudin, E.; Chevalier, B.; Méasson, M.-A.; Cano, A.; Tencé, S. (March 2018). "Iron-based superconductivity extended to the novel silicide LaFeSiH". Physical Review B. 97 (10): 100504. arXiv:1701.05010. Bibcode:2018PhRvB..97j0504B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.97.100504. ISSN 2469-9969. S2CID 119004395.

- ^ Sasmal, K.; Lv, Bing; Lorenz, Bernd; Guloy, Arnold M.; Chen, Feng; Xue, Yu-Yi; Chu, Ching-Wu (2008). "Superconducting Fe-Based Compounds (A1−xSrx) Fe2As2 with A=K and Cs with Transition Temperatures up to 37 K" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 101 (10): 107007. arXiv:0806.1301. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101j7007S. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.101.107007. PMID 18851250. S2CID 2425512.

- ^ Zhang, S. J.; Wang, X. C.; Liu, Q. Q.; Lv, Y. X.; Yu, X. H.; Lin, Z. J.; Zhao, Y. S.; Wang, L.; Ding, Y.; Mao, H. K.; Jin, C. Q. (2009). "Superconductivity at 31 K in the "111"-type iron arsenide superconductor Na1−xFeAs induced by pressure". EPL. 88 (4): 47008. arXiv:0912.2025. Bibcode:2009EL.....8847008Z. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/88/47008. S2CID 55588819.

- ^ Deng, Z.; Wang, X. C.; Liu, Q. Q.; Zhang, S. J.; Lv, Y. X.; Zhu, J. L.; Yu, R. C.; Jin, C. Q. (2009). "A new "111" type iron pnictide superconductor LiFeP". EPL. 87 (3): 37004. arXiv:0908.4043. Bibcode:2009EL.....8737004D. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/87/37004. S2CID 119227185.

- ^ Day, C. (2009). "Iron-based superconductors". Physics Today. 62 (8): 36–40. Bibcode:2009PhT....62h..36D. doi:10.1063/1.3206093.

- ^ Stewart, G. R. (2011). "Superconductivity in iron compounds". Rev. Mod. Phys. 83 (4): 1589–1652. arXiv:1106.1618. Bibcode:2011RvMP...83.1589S. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.83.1589. S2CID 119238477.

- ^ Yates, K A; Usman, I T M; Morrison, K; Moore, J D; Gilbertson, A M; Caplin, A D; Cohen, L F; Ogino, H; Shimoyama, J (2010). "Evidence for nodal superconductivity in Sr2ScFePO3". Superconductor Science and Technology. 23 (2): 022001. arXiv:0908.2902. Bibcode:2010SuScT..23b2001Y. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/23/2/022001. S2CID 119248392.

- ^ Dai, Jianhui; Si, Qimiao; Zhu, Jian-Xin; Abrahams, Elihu (2009-03-17). "Iron pnictides as a new setting for quantum criticality". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (11): 4118–4121. arXiv:0808.0305. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.4118D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900886106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2657431. PMID 19273850.

- ^ a b c A. A. Kordyuk (2012). "Iron-based superconductors: Magnetism, superconductivity, and electronic structure (Review Article)". Low Temp. Phys. 38 (9): 888. arXiv:1209.0140. Bibcode:2012LTP....38..888K. doi:10.1063/1.4752092. S2CID 117139280.

- ^ Luetkens, H; Klauss, H. H.; Kraken, M; Litterst, F. J.; Dellmann, T; Klingeler, R; Hess, C; Khasanov, R; Amato, A; Baines, C; Kosmala, M; Schumann, O. J.; Braden, M; Hamann-Borrero, J; Leps, N; Kondrat, A; Behr, G; Werner, J; Büchner, B (2009). "Electronic phase diagram of the LaO1−xFxFeAs superconductor". Nature Materials. 8 (4): 305–9. arXiv:0806.3533. Bibcode:2009NatMa...8..305L. doi:10.1038/nmat2397. PMID 19234445. S2CID 14660470.

- ^ Drew, A. J.; Niedermayer, Ch; Baker, P. J.; Pratt, F. L.; Blundell, S. J.; Lancaster, T; Liu, R. H.; Wu, G; Chen, X. H.; Watanabe, I; Malik, V. K.; Dubroka, A; Rössle, M; Kim, K. W.; Baines, C; Bernhard, C (2009). "Coexistence of static magnetism and superconductivity in SmFeAsO1−xFx as revealed by muon spin rotation". Nature Materials. 8 (4): 310–314. arXiv:0807.4876. Bibcode:2009NatMa...8..310D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.634.8055. doi:10.1038/nmat2396. PMID 19234446. S2CID 205402602.

- ^ Sanna, S.; De Renzi, R.; Lamura, G.; Ferdeghini, C.; Palenzona, A.; Putti, M.; Tropeano, M.; Shiroka, T. (2009). "Competition between magnetism and superconductivity at the phase boundary of doped SmFeAsO pnictides". Physical Review B. 80 (5): 052503. arXiv:0902.2156. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..80e2503S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.052503. S2CID 119247319.

- ^ Zhao, J; Huang, Q; de la Cruz, C; Li, S; Lynn, J. W.; Chen, Y; Green, M. A.; Chen, G. F.; Li, G; Li, Z; Luo, J. L.; Wang, N. L.; Dai, P (2008). "Structural and magnetic phase diagram of CeFeAsO1−xFx and its relation to high-temperature superconductivity". Nature Materials. 7 (12): 953–959. arXiv:0806.2528. Bibcode:2008NatMa...7..953Z. doi:10.1038/nmat2315. PMID 18953342. S2CID 25937023.

- ^ Chu, Jiun-Haw; Analytis, James; Kucharczyk, Chris; Fisher, Ian (2009). "Determination of the phase diagram of the electron doped superconductor Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2". Physical Review B. 79 (1): 014506. arXiv:0811.2463. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..79a4506C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.014506. S2CID 10731115.

- ^ "Press release: Japanese scientists use alcoholic drinks to induce superconductivity". Institute of Physics. 7 March 2011.

- ^ Deguchi, K; Mizuguchi, Y; Kawasaki, Y; Ozaki, T; Tsuda, S; Yamaguchi, T; Takano, Y (2011). "Alcoholic beverages induce superconductivity in FeTe1−xSx". Superconductor Science and Technology. 24 (5): 055008. arXiv:1008.0666. Bibcode:2011SuScT..24e5008D. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/24/5/055008. S2CID 93508333.

- ^ "Red Wine, Tartaric Acid, and the Secret of Superconductivity". MIT Technology Review. March 22, 2012.

- ^ Deguchi, K; Sato, D; Sugimoto, M; Hara, H; Kawasaki, Y; Demura, S; Watanabe, T; Denholme, S J; Okazaki, H; Ozaki, T; Yamaguchi, T; Takeya, H; Soga, T; Tomita, M; Takano, Y (2012). "Clarification as to why alcoholic beverages have the ability to induce superconductivity in Fe1+dTe1−xSx". Superconductor Science and Technology. 25 (8): 084025. arXiv:1204.0190. Bibcode:2012SuScT..25h4025D. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/25/8/084025. S2CID 119223257.

- ^ A. A. Kordyuk (2018). "Electronic band structure of optimal superconductors: from cuprates to ferropnictides and back again (Review Article)". Low Temp. Phys. 44 (6): 477–486. arXiv:1803.01487. Bibcode:2018LTP....44..477K. doi:10.1063/1.5037550. S2CID 119342977.

- ^ Ge, JF; Liu, ZL; Liu, C; Gao, CL; Qian, D; Xue, DK; Liu, Y; Jia, JF (2014). "Superconductivity above 100K in single-layer FeSe films on doped SrTiO3". Nat. Mater. 14 (3): 285–9. arXiv:1406.3435. doi:10.1038/NMAT4153. PMID 25419814. S2CID 119227626.