U.S. Route 2 in Michigan

US 2 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by MDOT | ||||

| Length | 305.151 mi[1][a] (491.093 km) | |||

| Existed | November 11, 1926[2]–present | |||

| Tourist routes |

| |||

| Western segment | ||||

| Length | 109.177 mi[1] (175.703 km) | |||

| West end | ||||

| Major intersections |

| |||

| East end | ||||

| Eastern segment | ||||

| Length | 195.974 mi[1] (315.390 km) | |||

| West end | ||||

| Major intersections | ||||

| East end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | United States | |||

| State | Michigan | |||

| Counties | Gogebic, Iron; Dickinson, Menominee, Delta, Schoolcraft, Mackinac | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

US Highway 2 (US 2) is a component of the United States Numbered Highway System that connects Everett, Washington, to the Upper Peninsula (UP) of the US state of Michigan, with a separate segment that runs from Rouses Point, New York, to Houlton, Maine. In Michigan, the highway runs through the UP in two segments as a part of the state trunkline highway system, entering the state at Ironwood and ending at St. Ignace; in between, US 2 briefly traverses the state of Wisconsin. As one of the major transportation arteries in the UP, US 2 is a major conduit for traffic through the state and neighboring northern Midwest states. Two sections of the roadway are included as part of the Great Lakes Circle Tours, and other segments are listed as state-designated Pure Michigan Byways. There are several memorial highway designations and historic bridges along US 2 that date to the 1910s and 1920s. The highway runs through rural sections of the UP, passing through two national and two state forests in the process.

The route of what became US 2 was used as part of two Indian trails before European settlers came to the UP, and as part of the Michigan segments of the Theodore Roosevelt International Highway and the King's International Highway auto trails in the early 20th century. The state later included these trails as part of M‑12 when the first state highway trunklines were designated in 1919. Most of M‑12 was redesignated as part of US 2 when the US Highway System was created on November 11, 1926. Since the 1930s, several changes have reshaped the highway's routing through the UP. One such alteration eventually created a business loop that connected across the state line with Hurley, Wisconsin, and others pushed an originally inland routing of US 2 closer to the Lake Michigan shoreline. With the creation of the Interstate Highway System, part of US 2 was rerouted to coincide with the new Interstate 75 (I‑75), though in the 1980s, the U.S. Highway was truncated and removed from the I‑75 freeway, resulting in today's basic form.

Route description

[edit]According to a 2006 regional planning committee report, US 2 is a key highway for Michigan, providing its main western gateway. The roadway plays "an important role in the transportation of goods across the northern tier of states in the Midwest",[3] and is listed on the National Highway System (NHS) for its entire length.[4] The NHS is a network of roadways important to the country's economy, defense, and mobility.[5] Together with M‑28, US 2 is part of a pair of primary trunklines that bridge the eastern and western sides of the UP.[6] The 305.151 miles (491.093 km) of roadway in Michigan is divided into a 109.177-mile (175.703 km) western segment and a 195.974-mile (315.390 km) eastern segment,[1] interrupted by a section that runs for 14.460 miles (23.271 km) in the state of Wisconsin.[7]

Western segment

[edit]US 2 enters Michigan from Wisconsin for the first time north of downtown Hurley, Wisconsin, and Ironwood, Michigan, over the state line that runs along the Montreal River. The highway crosses the river into Gogebic County and passes a welcome center on the way into a commercial district north of downtown. Running along Cloverland Drive, US 2 meets its only business route in Michigan at Douglas Boulevard.[6][8] The business route was previously a full loop that ran west through downtown Ironwood and crossed the border into Hurley and back to the main highway. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation has removed the signage on their side of the border, which reduced the loop to a business spur that ends at the state line.[9][10] US 2 continues eastward through UP woodlands to the city of Bessemer. While bypassing the community of Ramsay, the highway crosses a branch of the Black River. The roadway enters Wakefield on the south side of Sunday Lake, meeting M‑28 at a stoplight in town. As the US Highway leaves Wakefield, it turns southeasterly through the Ottawa National Forest,[8][11] crossing Jackson Creek and two branches of the Presque Isle River. US 2 and M‑64 merge and run concurrently over the second branch of the Presque Isle in the community of Marenisco.[6][8][11] This concurrency has the lowest traffic volume along the entire length of the highway within the state; in 2010 the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) recorded a daily average usage along the stretch of 770 vehicles, compared to the overall average of 5,188 vehicles for the highway.[12] At the end of the concurrency, M‑64 turns northerly to run along Lake Gogebic.[6][8][11]

The highway continues parallel to the state line from the Marensico area through the national forest toward Watersmeet, where it crosses US 45. That unincorporated community is the home of the Watersmeet High School Nimrods, the basketball team featured on a series of ESPN commercials and a documentary series on the Sundance Channel.[13] The area is also where the waters meet; the rolling hills drain to Lake Superior via the Ontonagon River, to Lake Michigan via the Brule and Menominee rivers, or to the Gulf of Mexico via the Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers. Also located in the area are the Sylvania Wilderness, and the Lac Vieux Desert Indian Reservation, which includes the Lac Vieux Desert Casino and Resort.[14] The highway travels southeasterly from Watersmeet around the many lakes and streams in the area and crosses into rural Iron County. US 2 intersects Federal Forest Highway 16 (FFH 16) near Golden Lake in Stambaugh Township in the middle of the national forest. The trunkline then runs along the Iron River as it approaches the city of the same name and meets M‑73. In town, US 2 intersects M‑189 before crossing the river and turning northeast out of the city.[6][8][11]

US 2 leaves the Ottawa National Forest at Iron River,[11] and the highway continues eastward through forest lands near several small lakes to Crystal Falls, the county seat of Iron County. On the west side of town, US 2 meets US 141; the two highways run concurrently along Crystal Avenue. The combined highway turns south onto 5th Street and meets M‑69's eastern terminus at the intersection between 5th Street and Superior Avenue next to the county courthouse at the top of the hill. US 2/US 141 runs south out of Crystal Falls to the west of, and parallel to, the Paint River. The roadway passes Railroad, Kennedy and Stager lakes and leaves the state of Michigan at the Brule River,[6][8] crossing into Florence County, Wisconsin for about 14 miles (23 km).[7]

Eastern segment

[edit]US 2/US 141 re-enters Michigan where it crosses the Menominee River and subsequently meets M‑95 in Breitung Township north of Iron Mountain and Kingsford. The highways merge in a triple concurrency and run south on Stephenson Avenue into Iron Mountain along the west side of Lake Antoine, parallel to a branch line of the Escanaba and Lake Superior Railroad (ELS Railroad).[8][15] The road crosses through a retail corridor and over a flooded pit of the Chapin Mine. In downtown Iron Mountain at Ludington Street, M‑95 turns west off Stephenson Avenue to run across town to Kingsford. US 2/US 141 exits downtown and turns east along a second retail corridor near the Midtown Mall. The highway re-enters Breitung Township where US 141 separates to the south to re-enter Wisconsin.[8] US 2 continues eastward parallel to a branch of the Canadian National Railway (CN Railway).[15] Both road and rail travel through the community of Quinnesec, where they pass near the largest paper mill in the UP.[16] The trunkline runs along the main street of Norway, where the highway meets the eastern terminus of US 8. Then US 2 continues east through rural Dickinson County to Vulcan, passing north of Hanbury Lake through the Copper Country State Forest, before crossing the Sturgeon River in Loretto and passing into Menominee County.[6][8]

In Menominee County, the environment takes on a more agricultural character along US 2. The highway passes through the edge of the community of Hermansville before entering Powers. US 2 comes to a three-way intersection and turns northeast merging onto US 41. The concurrent highway runs from Powers through the communities of Wilson and Spaulding on the south side of the CN Railway. At Harris, the trunkline enters the Hannahville Indian Community. Harris is on the Menominee County side of the reservation, but as the highway continues east, it crosses over to Bark River on the Delta County side. The county line in between not only separates the two communities, but also serves as the boundary between the Central and Eastern time zones. East of Bark River, the highway crosses the community's namesake waterway before intersecting the eastern terminus of M‑69. The roadway crosses the Ford River prior to turning due east into the outskirts of Escanaba.[6][8]

US 2/US 41 widens to four lanes along Ludington Street, which forms the east–west axis of the Escanaba street grid. Near downtown, the highway meets M‑35, which runs along the city's north–south axis, Lincoln Road. The trunklines merge and run north, bypassing the traditional central business district for a different business corridor.[8] Lincoln Road runs north carrying four lanes of traffic past the Upper Peninsula State Fairgrounds, site of one of the two state fairs for the state of Michigan, the only state to have twin fairs.[17] US 2/US 41/M‑35 continues north on Lincoln Road past the campus of Bay de Noc Community College. The four-lane highway crosses the Escanaba River just upstream from its mouth near the large Verso Esky Paper Mill and shifts to run immediately next to Little Bay de Noc.[6][8][17] The section here carried the highest traffic counts along all of US 2 in the state: an average of 23,977 vehicles used this segment of roadway daily in 2011.[12]

The road turns inland again, and US 2/US 41/M‑35 passes to the west of downtown Gladstone. The highway through here is an expressway, four lanes divided by a central median and no driveway access. Unlike a freeway, the expressway has standard intersections and not interchanges. The highway intersects the eastern terminus of County Road 426 (CR 426) and crosses the ELS Railroad south of the stoplight for 4th Avenue North, where M‑35 separates from the US Highways and turns to the northwest. The expressway continues north parallel to the CN Railway, crossing the Days River.[6][8] From Gladstone to St. Ignace, US 2 carries a speed limit of 65 mph (105 km/h) for all traffic.[18] This was, before 2017, the only road in the UP with a speed limit higher than 55 mph (89 km/h) besides I-75, which has a speed limit of 75 mph (121 km/h).[19] The expressway segment runs around the upper end of Little Bay de Noc before ending at Rapid River. In this location, US 41 separates to the north, and US 2 returns to an easterly track as a two-lane road, crossing the Rapid and Whitefish rivers and turning southeast around the head of the bay.[6] As US 2 crosses southern Delta County, it passes through the western unit of the Hiawatha National Forest.[11] Near Garden Corners, the highway runs along the shore of Big Bay de Noc. After the intersection with the northern terminus of M‑183, US 2 turns inland cutting across the base of the Garden Peninsula and enters Schoolcraft County.[6]

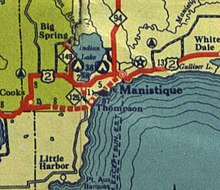

As the highway approaches Thompson, US 2 leaves the western unit of the Hiawatha National Forest and enters the Lake Superior State Forest.[8][11] The roadway runs along Lake Michigan to Manistique, crossing the Manistique River. The trunkline turns inland approaching Gulliver and then turns north-northeast to Blaney Park.[6] The community of Blaney Park is a former logging town-turned-resort at the southern terminus of M‑77; the resort was active from the late 1920s but declined by the 1980s.[20] From Blaney Park, US 2 turns due east and crosses into Mackinac County west of Gould City. Where it intersects a former routing, the main highway crosses the CN Railway one last time and runs to the south of Engadine to follow the Lake Michigan shoreline through Naubinway.[6] After passing the community of Epoufette,[8] US 2 crosses the Cut River Bridge, 147 feet (45 m) over the Cut River.[21] The highway crosses into the eastern unit of the Hiawatha National Forest near Brevort, running between Lake Michigan and Brevoort Lake in the process.[11] The road continues along the Lake Michigan shoreline, passing Mystery Spot near Gros Cap and turning inland immediately west of St. Ignace. The US 2 designation ends at the highway's partial cloverleaf interchange with I‑75. The roadway continues easterly into downtown St. Ignace as Business Loop I‑75 (BL I‑75).[6][8]

History

[edit]Indian trail through auto trails

[edit]In 1701, the first transportation routes through what became the state of Michigan were the lakes, rivers and Indian trails. Two of these trails followed parts of the future US 2. The Sault–Green Bay Trail roughly followed the Lake Michigan shoreline routing of US 2 between Escanaba and St. Ignace. The Mackinac Trail connected St. Ignace with Sault Ste. Marie.[22]

In the age of the auto trail, the roads that later formed US 2 through the UP were given a few different highway names. When the original roadways between Ironwood and Iron River were completed in late 1915, the Upper Peninsula Development Bureau (UPDB) named the area Cloverland and the highway the Cloverland Trail. Later the name was extended over the highway to Escanaba, and to all highways in the area in the early 1920s; the name was phased out by the UPDB completely in 1927.[23] The roadways were also used for the Theodore Roosevelt International Highway, named for former US president Theodore Roosevelt after his death in 1919. Overall, this highway ran from Portland, Oregon, to Portland, Maine, by way of Michigan and the Canadian province of Ontario. Through the UP, the southern branch followed the immediate predecessors to US 2, including the section through Florence County, Wisconsin.[24][b]

The Great Lakes Automobile Route was established in 1917 by the UPDB. A predecessor of the Great Lakes Circle Tours by seventy years, the route followed "a circular journey along the banks of lakes Michigan and Superior and Green Bay ..."[25] This route followed the modern US 2 from Ironwood to the M‑94 junction in Manistique, using the modern M‑69 and M‑95 to stay in Michigan. Branches of the route followed US 41 and M‑35 between Powers and Escanaba. The route was originally intended to entice motorists to drive around Lake Michigan. The name fell out of use before its first anniversary because of World War I.[25]

One Canadian auto trail was routed through the UP as well. In 1920, the King's International Highway linked Vancouver, British Columbia, to Halifax, Nova Scotia, but there was no highway to carry it around the north side of Lake Superior. Motorists had to ship their cars by boat between Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, and Thunder Bay or enter the United States to continue along the auto trail. The routings varied on the maps of the time, but its basic route used US 2 through the UP from Ironwood to Sault Ste. Marie until a highway north of Lake Superior was opened in 1960; by that time, the auto trail had taken on the Trans-Canada Highway name.[26]

State trunkline

[edit]The first state trunkline highway designated along the path of the modern US 2 was M‑12, a designation that was in use by July 1, 1919, between Ironwood and Sault Ste. Marie.[27][c] The first roadside park in the country was created by Herbert Larson near what is now US 2 near Iron River in 1919–20.[29] When the US Highway System was created on November 11, 1926,[2] US 2 partially replaced M-12.[30] Between Crystal Falls and Iron Mountain, US 2 was routed through Florence, Wisconsin. The former routing of M‑12 from Crystal Falls to Sagola became a new M‑69 when the former M‑69 became US 102 (now US 141). M‑12 from Sagola south to Iron Mountain was made a part of an extended M‑45, which is now M‑95. By the next year, M‑48 was added along US 2 from Rexton to Garnet as part of a larger extension.[31]

The first changes to the routing of US 2 itself were made in 1930 with a bypass of downtown Escanaba.[32][33] A larger rerouting was completed in 1933 between Rogers Park and Sault Ste. Marie. The new routing followed Mackinac Trail instead of turning east to Cedarville and north to Sault Ste. Marie; the former routing was given the M‑121 designation.[34][35] Another realignment in the Iron Mountain area shifted US 2/US 141 to a new bridge over the Menominee River between 1932 and 1934.[36][37] Downtown Ironwood was bypassed in 1934, and the former route was initially designated M‑54.[35][37]

The Michigan State Highway Department (MSHD)[d] changed the routings and designations of the highways around Cooks, Thompson and Manistique in the mid-1930s. The agency rerouted US 2 between Cooks and M‑149 in Thompson, turning the old road back to county control. The section between M‑149 and M‑125 was redesignated as an extension of M‑149 to Thompson, and M‑125 was replaced by a further extension of M‑149. The last change was to route US 2 along its current alignment in the area, completing the changes on August 2, 1936.[40][41]

The MSHD started construction in 1936 on a new road that rerouted US 2 into St. Ignace for the first time. Between Brevort and Moran, US 2 previously followed Worth Road inland to the Tahquamenon Trail to meet the northern extension of US 31 into the Upper Peninsula.[42] The new routing took US 2 along the lakeshore into St. Ignace. US 31 was truncated to the state ferry docks in Mackinaw City and US 2 was routed through St. Ignace along the former US 31 to Rogers Park; the connection in St. Ignace to the state ferry docks became M‑122.[40] Further changes in the early 1940s straightened the roadway out near Watersmeet and Crystal Falls.[43][44]

Additional realignments were completed by the MSHD to move US 2 to its modern lakeshore routing between Gould City and Epoufette in 1941. The new highway traveled due east from Gould City to Naubinway and then along the lake to Epoufette. The former route through Engadine was turned back to local control as far east as Garnet. From there east, it was numbered just M‑48, removing US 2 from a concurrency. Another former section into Epoufette was added to extend M‑117.[45] The new highway was detoured around the Cut River Bridge until it was completed in 1946 after construction delays over steel shortages during World War II.[46][47]

The western end of US 2 took on two changes in the 1940s. M‑28 was extended along US 2 to the state line at Ironwood from its western terminus at Wakefield.[45] A similar extension was made from M‑28's eastern terminus to Sault Ste. Marie in 1948.[48] The M‑54 designation was renumbered as Business US 2 by 1945.[47] The eastern M‑28 extension was reversed in 1950,[49] and the western extension to the state line was shifted to a new location by 1952.[50]

Interstate era

[edit]

With the coming of the Interstate Highway System in Michigan, the MSHD planned to convert the eastern section of US 2 to a freeway between St. Ignace and Sault Ste. Marie. In planning maps from 1947, this highway corridor was included in the system that later became the Interstates.[51] It was also included in the General Location of National System of Interstate Highways Including All Additional Routes at Urban Areas Designated in September 1955, or Yellow Book after the cover color, that was released in 1955 as the federal government readied plans for the freeway system.[52] The proposed number in 1958 was Interstate 75 (I‑75).[53]

The first section of freeway was built in late 1957 or early 1958 between Evergreen Shores and M‑123 north of St. Ignace.[54][55] The Mackinac Bridge was opened to traffic on November 1, 1957;[56] a new section of freeway and an interchange connected US 2 to the bridge.[57] In 1961, another new freeway segment closed the gap between the Mackinac Bridge and Evergreen Shores sections. At the time, the I‑75 designation supplanted US 27 on the bridge, and US 2 was shifted to follow I‑75 along the freeways in the St. Ignace area. The former routing of US 2 in downtown St. Ignace was redesignated BL I‑75.[58] More sections of freeway were opened in 1962 immediately to the south of the newly constructed International Bridge in Sault Ste. Marie as well as between Dafter and Kinross.[59][60] The last two sections opened in 1963 connected the northern end of the freeway at M‑123 to Kinross, and the section between Dafter and Sault Ste. Marie. At this time, all of US 2's former routing became a county road known as Mackinac Trail (H-63).[60][61]

The Department of State Highways[d] expanded US 2/US 41 into an expressway between Gladstone and Rapid River in 1971.[62][63] The state built a new bridge over the Manistique River in 1983, bypassing downtown. MDOT disposed of the former routing of US 2 into downtown in two ways. The western half was initially an unnumbered state highway until it was later transferred to local control. An extension of M‑94 replaced the remainder, including the Siphon Bridge, through downtown. In that same year, the department truncated US 2 to end in St. Ignace by removing it from the I‑75 freeway.[64][65] The last changes were made to US 2's routing through Iron River in 1998, bypassing the bridge that formerly carried the highway over the river in town.[66] In 2011, MDOT raised the speed limit along the expressway section in Delta County from 55 to 65 mph (89 to 105 km/h), although the speed limit for trucks remained 55 mph (89 km/h)[19] until 2017. That year the highway's speed limits were raised to 65 mph (105 km/h) between Wakefield and Iron River as well as between Rapid River and St. Ignace.[18] In 2020, MDOT announced the slight relocation of US 2 in Mackinac County just west of the Cut River Bridge due to sinkholes and shoreline erosion on Lake Michigan near the roadway.[67]

Memorial designations and tourist routes

[edit]On July 1, 1924, the State Administrative Board named M‑12, the predecessor to US 2 in Michigan, the Bohn Highway to honor Frank P. Bohn, a prominent local citizen who later served in Congress from 1927 to 1933.[68] In 1929, the residents of Escanaba created a memorial to the veterans of World War I called Memory Lane. The project consisted of elm and maple trees planted along US 2/US 41 west of town. The American Legion sold the trees to local businesses and individuals who could honor specific soldiers.[69] Later in 1949, the Bessemer Women's Club created a tribute in the form of a permanent living memorial to the area veterans. Also called Memory Lane, the group planted 140 elms and 1,840 evergreens, trees and shrubs as a landscaped parkway along 2.3 miles (3.7 km) of US 2 east of Bessemer.[70]

Most of US 2, along with US 23 in the Lower Peninsula, was designated the United Spanish War Veterans Memorial Highway in 1949. To connect the gap in the routing where US 2 cuts through Wisconsin, M‑95 and M‑69 were used in place of US 2 between Iron Mountain and Crystal Falls. Signs marking the highway were not erected until 1968 when Governor George W. Romney had them installed.[71]

The Amvets Memorial Drive designation was created for the section of US 2/US 41/M‑35 between the northern Escanaba city limits and County Road 426 (CR 426) in Delta County. The American Veterans (AMVETS) organization in Michigan petitioned the Michigan Legislature to grant this designation, which was assigned under Public Act 144 in 1959.[72]

Two sections of US 2 are part of the overall Great Lakes Circle Tour (GLCT): the segment from the Wisconsin state line near Ironwood to the M‑28 junction in Wakefield is part of the Lake Superior Circle Tour (LSCT), and the segment from the southern M‑35 junction in Escanaba to the eastern terminus in St. Ignace is part of the Lake Michigan Circle Tour (LMCT).[6] These two tours were created in May 1986 through a joint effort between MDOT and its counterparts in Wisconsin, Minnesota and Ontario.[73] The section of US 2 between Iron River and Crystal Falls has been named the Iron County Heritage Trail. This Pure Michigan Byway was designated to honor the "rich history of two industries that built a state and nation: mining and logging."[74] On August 26, 2007, MDOT announced that the section of US 2 that runs concurrently with M‑35 in Delta County was being included in the UP Hidden Coast Recreational Heritage Trail.[75][76] The segment between Thompson and St. Ignace along the northern shore of Lake Michigan was designated the Top of the Lake Scenic Byway in the Pure Michigan Byways program on October 9, 2017.[77]

Historic bridges

[edit]There are six bridges along current or former sections of US 2 that MDOT has added to its listing of Michigan's Historic Bridges; two of these are also listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). A third bridge added to the NRHP in late 2012 has not been added to MDOT's listing however. The first of these historic bridges is the crossing of the Iron River,[66] which has since been bypassed by a new bridge.[78] The original structure, dating to 1918, is a 55-foot-long (17 m) spandrel arch span that was built by the MSHD as Trunk Line Bridge No. 191.[66] The structure was listed on the NRHP on December 9, 1999, for its architectural and engineering significance.[79]

In December 2012, the National Park Service approved the listing of the Upper Twin Falls Bridge that crosses the Menominee River northwest of Iron Mountain. The structure is a single-span, pin-connected, camelback, through-truss bridge, and it is the only known example of its type in Michigan. It was built between 1909 and 1910 because the Twin Falls Power Dam would flood an existing river crossing. The span cost $5,106 (equivalent to $121,000 in 2023[80]), paid equally by Dickinson and Florence counties.[81] Until the 1930s, the Upper Twin Falls Bridge carried US 2 across the Menominee River.[82] In 1934, a new bridge was built about a mile downstream, and the highway was rerouted over the new span.[83] The bridge closed to automobile traffic in September 1971,[84] and the nomination process for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places began in 2012.[81]

In 2003, MDOT replaced the Sturgeon River Bridge in Waucedah Township, Dickinson County.[85] As of October 2011[update], even though the old bridge was demolished and replaced, MDOT retained it on their historic bridge list. It was built in 1929.[86]

Before 1983, US 2 used a different routing through Manistique and crossed the Manistique River on what is nicknamed the "Siphon Bridge". Built as a part of a raceway flume on the river, the water level is actually higher than the road surface. This produces a siphon effect, giving the bridge its nickname. The Manistique Pulp and Paper Company was organized in 1916 and needed a dam on the Manistique River to supply their mill. This dam would require a large section of the city to be flooded, and shallow river banks meant difficulties in any bridge construction. Instead of expensive dikes, a concrete tank was built lengthwise in the river bed; the sides of this tank provided man-made banks higher than the natural banks. The Michigan Works Progress Administration described the bridge as having "concrete bulkheads, formed by the side spans of the bridge, [that] allow the mill to maintain the water level several feet above the roadbed."[87] The Manistique Tourism Council stated: "At one time, the bridge itself was partially supported by the water that was atmospherically forced under it," and that the bridge has been featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!.[88] The eight-span structure is 294 feet (90 m) long.[89]

The Cut River Bridge carries US 2 across the Cut River in Hendricks Township, Mackinac County. This structure was built during World War II but completion was delayed due to war-induced steel shortages.[46] The span uses 888 short tons (793 long tons; 806 t) of structural steel to bridge the 641 feet (195 m) over the river and its gorge at a height of 147 feet (45 m) above the river. The Cut River Bridge is one of only two cantilevered deck truss bridges in the state.[90][e] On either side of the bridge, there are picnic areas and trails down to the river.[91]

Listed on the NRHP on December 17, 1999,[79] the Mackinac Trail–Carp River Bridge carries H-63, the modern successor to US 2, over the Carp River north of St. Ignace. The bridge is another spandrel arch structure 60 feet (18 m) in length and built in 1920. Increasing traffic along Mackinac Trail prompted the MSHD to "widen its deck by five feet [1.5 m] and install new guardrails in the 1929–1930 biennium" along with the addition of decorative retaining walls.[92]

The last of the historic bridges along a former segment of US 2 is the structure carrying Ashmun Street (BS I‑75) over the Power Canal in Sault Ste. Marie. Built in 1934, it is one of only three steel arch bridges in the state.[93][f] The 42-foot-wide (13 m) and 257-foot-long (78 m) structure is described by MDOT as "massive" with an "innovative" construction method: the previous structure was used as a falsework for the current bridge before removal.[95]

Major intersections

[edit]MDOT has erected milemarkers along the two Michigan segments of the highway that use the total mileage starting at the state line in Ironwood; the signs on the eastern segment reflect the mileage in Florence County, Wisconsin.

| County | Location | mi[1] | km | Destinations | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal River | 0.000 | 0.000 | Continuation into Wisconsin | ||||

| Gogebic | Ironwood | 1.136 | 1.828 | ||||

| Wakefield | 12.543 | 20.186 | Western terminus of M-28; eastern end of LSCT concurrency | ||||

| Marenisco | 26.072 | 41.959 | Western end of M-64 concurrency | ||||

| Marenisco Township | 28.153 | 45.308 | Eastern end of M-64 concurrency | ||||

| Watersmeet | 53.792 | 86.570 | |||||

| Iron | Stambaugh Township | 70.137 | 112.875 | Marked as H-16 on MDOT maps | |||

| Iron River Township | 82.054 | 132.053 | Northern terminus of M-73 | ||||

| Iron River | 83.505 | 134.388 | Northern terminus of M-189 | ||||

| Crystal Falls Township | 97.991 | 157.701 | Northern end of US 141 concurrency | ||||

| Crystal Falls | 99.147 | 159.562 | Western terminus of M-69 | ||||

| Brule River | 109.177 | 175.703 | Continuation into Wisconsin | ||||

| US 2/US 141 enters Wisconsin and travels 14.460 miles before re-entering Michigan.[7] | |||||||

| Menominee River | 123.637 | 198.974 | Continuation into Wisconsin | ||||

| Dickinson | Breitung Township | 124.302 | 200.045 | Northern end of M-95 concurrency | |||

| Iron Mountain | 127.649 | 205.431 | Southern end of M-95 concurrency | ||||

| Breitung Township | 130.513 | 210.040 | Southern end of US 141 concurrency | ||||

| Norway | 136.104 | 219.038 | Eastern terminus of US 8 | ||||

| Waucedah Township | 144.558 | 232.644 | Southern terminus of G-69 | ||||

| Menominee | Powers | 157.322 | 253.185 | Western end of US 41 concurrency | |||

| Delta | Bark River Township | 170.197 | 273.906 | Eastern terminus of M-69 | |||

| Escanaba | 179.308 | 288.568 | Southern end of M-35 concurrency; western end of LMCT concurrency | ||||

| Gladstone | 186.316 | 299.847 | |||||

| 187.726 | 302.116 | Northern end of M-35 concurrency | |||||

| Masonville Township | 193.639 | 311.632 | Former M-186 | ||||

| Rapid River | 193.914 | 312.074 | Eastern end of US 41 concurrency | ||||

| Nahma Junction | 208.135 | 334.961 | Southern terminus of H-13/FFH 13 | ||||

| Garden Corners | 216.702 | 348.748 | Northern terminus of M-183 | ||||

| Schoolcraft | Thompson | 227.266 | 365.749 | Southern terminus of M-149 | |||

| Manistique | 232.743 | 374.564 | Southern terminus of M-94 | ||||

| Mueller Township | 254.359 | 409.351 | Southern terminus of M-77 | ||||

| Mackinac | Newton Township | 263.428 | 423.946 | Southern terminus of H-33; former M-135 | |||

| Garfield Township | 271.440 | 436.840 | Southern terminus of M-117 | ||||

| Hendricks Township | 294.380 | 473.759 | Cut River Bridge | ||||

| Moran Township | 308.642 | 496.711 | Southern terminus of H-57 | ||||

| St. Ignace | 319.611 | 514.364 | Eastern terminus of the western US segment of US 2; roadway continues east as BL I-75; LMCT continues southward on I-75; exit 344 on I-75 | ||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||||

Business route

[edit]| Location | Ironwood |

|---|---|

| Length | 1.270 mi[1] (2.044 km) |

| Existed | August 1942[96]–present |

Business U.S. Highway 2 (Bus. US 2) is a 1.270-mile (2.044 km) business route that runs from the Wisconsin state line at the Montreal River. The route extends through downtown Ironwood on Silver and Aurora streets before turning northward along Suffolk Street. Bus. US 2 stays on Suffolk Street for a short while until it turns onto Frederick Street. On Frederick Street, Bus. US 2 bears north through a residential area along Douglas Street. The eastern terminus of the route is at its junction with US 2 at the corner of Cloverland Drive and Douglas Street north of downtown.[1][97]

The business route was created in August 1942 when former M‑54 in Ironwood was renumbered as a business loop of US 2.[96] It was originally a bi-state business connection before the Wisconsin Department of Transportation decommissioned Bus. US 2 in Hurley westward along State Trunk Highway 77 and northward along US 51 in 2002.[9][10]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Milemarkers on the eastern segment reflect the mileage in Florence County, Wisconsin.

- ^ The northern branch of the Theodore Roosevelt International Highway followed M-28.[24]

- ^ The first state highways in Michigan were signposted in 1919.[28]

- ^ a b The Michigan State Highway Department was reorganized into the Michigan Department of State Highways and Transportation on August 23, 1973.[38] The name was shortened to its current form in 1978.[39]

- ^ The other cantilevered deck truss bridge is the Mortimer E. Cooley Bridge on M‑55 across the Pine River in Manistee County.[46]

- ^ The other two are the M‑28–Ontonagon River Bridge and the International Bridge in Sault Ste. Marie.[94]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Michigan Department of Transportation (2021). Next Generation PR Finder (Map). Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ a b McNichol, Dan (2006). The Roads that Built America. New York: Sterling. p. 74. ISBN 1-4027-3468-9. OCLC 63377558.

- ^ Gogebic County Access Management Team (May 2006). US 2 Ironwood Corridor Access Management Plan (PDF) (Report). Western Upper Peninsula Planning and Development Region. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (April 23, 2006). National Highway System, Michigan (PDF) (Map). Scale not given. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ Natzke, Stefan; Neathery, Mike & Adderly, Kevin (June 20, 2012). "What is the National Highway System?". National Highway System. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Michigan Department of Transportation (2010). Uniquely Michigan: Official Department of Transportation Map (Map). c. 1:975,000. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. §§ B1–D10. OCLC 42778335, 639960603.

- ^ a b c Wisconsin Department of Transportation Region 4 (December 31, 2008). State Trunk Highway Log for Region 4. Rhinelander: Wisconsin Department of Transportation.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Google (September 15, 2010). "Overview Map of US 2" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Wisconsin Department of Transportation (2001). Official State Highway Map (Map) (2001–02 ed.). 1:823,680. Madison: Wisconsin Department of Transportation. § E2.

- ^ a b Wisconsin Department of Transportation (2003). Official State Highway Map (Map) (2003–04 ed.). 1:823,680. Madison: Wisconsin Department of Transportation. § E2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rand McNally (2008). "Michigan" (Map). The Road Atlas. 1:1,267,200 and 1:1,900,800. Chicago: Rand McNally. p. 50. §§ B10–D14, F1–E8. ISBN 0-528-93981-5. OCLC 226315010.

- ^ a b Bureau of Transportation Planning (2008). "Traffic Monitoring Information System". Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Jensen, Elizabeth (November 25, 2007). "And That's the News From Watersmeet". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ Hunt, Mary & Hunt, Don (2007). "Watersmeet Area". Hunt's Guide to Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Albion, Michigan: Midwestern Guides. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Michigan Department of Transportation (April 2009). Michigan's Railroad System (PDF) (Map). Scale not given. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Hunt & Hunt (2007), "Iron Mountain".

- ^ a b Hunt & Hunt (2007), "Escanaba".

- ^ a b "Some Michigan Highways Will Get a Speed Limit of 75 MPH: And 900 Miles of Roads will get 65-MPH Limit". Detroit Free Press. Associated Press. April 27, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Lancour, Jenny (January 19, 2011). "Speed Limit on US 2, 41 Will Rise". Daily Press. Escanaba, Michigan. OCLC 9671025. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ Hunt & Hunt (2007), "Blaney Park".

- ^ Batchelder, John & Paramski, Pete (September 2009). "Redecking Michigan's Cut River Bridge". Rebuilding America's Infrastructure. Vol. 1, no. 3. Fayetteville, Arkansas: ZweigWhite. pp. 24–7. ISSN 2162-7169. OCLC 744575701. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ Mason, Philip P. (1959). Michigan Highways from Indian Trails to Expressways. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Braun-Brumfield. p. 4. OCLC 23314983.

- ^ Barnett, LeRoy (2004). A Drive Down Memory Lane: The Named State and Federal Highways of Michigan. Allegan Forest, Michigan: Priscilla Press. pp. 57–8. ISBN 1-886167-24-9. OCLC 57425393.

- ^ a b Barnett (2004), p. 211.

- ^ a b Barnett (2004), pp. 96–7.

- ^ Barnett (2004), p. 127.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (July 1, 1919). State of Michigan (Map). Scale not given. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. Upper Peninsula sheet. OCLC 15607244. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via Michigan State University Libraries.

- ^ "Michigan May Do Well Following Wisconsin's Road Marking System". The Grand Rapids Press. September 20, 1919. p. 10. OCLC 9975013.

- ^ Bleck, Christine (April 20, 2015). "Roadside Relief: Parks, Rest Areas, Scenic Turnouts Aid Travelers". The Mining Journal. Marquette, Michigan. p. 1A. ISSN 0898-4964. OCLC 9729223.

- ^ Bureau of Public Roads & American Association of State Highway Officials (November 11, 1926). United States System of Highways Adopted for Uniform Marking by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). 1:7,000,000. Washington, DC: U.S. Geological Survey. OCLC 32889555. Retrieved November 7, 2013 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (December 1, 1927). Official Highway Service Map (Map). [c. 1:810,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. OCLC 12701195, 79754957.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department & H.M. Gousha (January 1, 1930). Official Highway Service Map (Map). [c. 1:810,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. OCLC 12701195, 79754957.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department & H.M. Gousha (July 1, 1930). Official Highway Service Map (Map). [c. 1:810,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. OCLC 12701195, 79754957.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (May 1, 1933). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:840,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C11–D11. OCLC 12701053. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via Archives of Michigan.

- ^ a b Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (September 1, 1933). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:840,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C11–D11. OCLC 12701053.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (April 1, 1932). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:840,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C1, D5. OCLC 12701053.

- ^ a b Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (September 1, 1934). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:850,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C1, D5. OCLC 12701143.

- ^ Kulsea, Bill & Shawver, Tom (1980). Making Michigan Move: A History of Michigan Highways and the Michigan Department of Transportation. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. p. 27. OCLC 8169232. Retrieved January 18, 2021 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Kulsea & Shawver (1980), pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (December 15, 1936). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map) (Winter ed.). [c. 1:850,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § D7. OCLC 12701143, 317396365. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ "Dedicate Highway Today". The Escanaba Daily Press. August 2, 1936. p. 4. Retrieved July 13, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (June 1, 1936). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:850,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § D7. OCLC 12701143.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (December 1, 1939). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map) (Winter ed.). [c. 1:850,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C2–D3. OCLC 12701143. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (July 1, 1941). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map) (Summer ed.). [c. 1:850,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C2–D3. OCLC 12701143. Archived from the original on April 22, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2017 – via Archives of Michigan.

- ^ a b Michigan State Highway Department & Rand McNally (June 1, 1942). Official Michigan Highway Map (Map) (Summer ed.). [c. 1:850,000]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C1, D10. OCLC 12701143.

- ^ a b c Hyde, Charles K. (1993). Historic Highway Bridges of Michigan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-8143-2448-7. OCLC 27011079. Retrieved September 7, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ a b Michigan State Highway Department (October 1, 1945). Official Highway Map of Michigan (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C1, D10. OCLC 554645076.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (July 1, 1948). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § C11. OCLC 12701120. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (April 15, 1950). Michigan Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § C1. OCLC 12701120.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (April 15, 1952). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § C1. OCLC 12701120. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ Public Roads Administration (August 2, 1947). National System of Interstate Highways (Map). Scale not given. Washington, DC: Public Roads Administration. Retrieved September 4, 2010 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Bureau of Public Roads (September 1955). General Location of National System of Interstate Highways Including All Additional Routes at Urban Areas Designated in September 1955 (Map). Scale not given. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 4165975. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (April 25, 1958). "Recommended Interstate Route Numbering for Michigan". Michigan State Highway Department. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (October 1, 1957). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § D10. OCLC 12701120, 367386492.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (1958). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § D10. OCLC 12701120, 51856742. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center. (Includes all changes through July 1, 1958)

- ^ Kulsea & Shawver (1980), p. 22.

- ^ "Approaches Completed". The State Journal. Lansing. October 30, 1957. p. 33. OCLC 9714548. Retrieved August 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (1961). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § C11. OCLC 12701120, 51857665. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center. (Includes all changes through July 1, 1961)

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (1962). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. § C11. OCLC 12701120, 173191490. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ a b Michigan State Highway Department (1963). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C10–C11. OCLC 12701120. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (1964). Official Highway Map (Map). [c. 1:918,720]. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. §§ C10–C11. OCLC 12701120, 81213707. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ Michigan Department of State Highways (1971). Michigan, Great Lake State: Official Highway Map (Map). c. 1:918,720. Lansing: Michigan Department of State Highways. § D6. OCLC 12701120, 77960415.

- ^ Michigan Department of State Highways (1972). Michigan, Great Lake State: Official Highway Map (Map). c. 1:918,720. Lansing: Michigan Department of State Highways. § D6. OCLC 12701120.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (1983). Say Yes to Michigan!: Official Transportation Map (Map). c. 1:918,720. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. §§ C10–C11. OCLC 12701177. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (1984). Say Yes to Michigan!: Official Transportation Map (Map). c. 1:918,720. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. §§ C10–C11. OCLC 12701177. Retrieved October 17, 2019 – via Michigan History Center.

- ^ a b c Michigan Department of Transportation (May 10, 2002). "US 2–Iron River". Michigan's Historic Bridges. Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ "US 2 Relocation Project Starts April 27 in Mackinac County". Upper Michigan's Source. Negaunee, Michigan: WLUC-TV. April 22, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Barnett (2004), pp. 36–7.

- ^ Barnett (2004), p. 151.

- ^ Barnett (2004), p. 149.

- ^ Barnett (2004), pp. 216–7.

- ^ Barnett (2004), p. 24.

- ^ Davis, R. Matt (May 1, 1986). "Signs to Mark Lake Circle Tour". The Daily Mining Gazette. Houghton, Michigan. p. 16. OCLC 9940134.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (December 8, 2010). "US 2: Iron County Heritage Trail". Interactive Heritage Route Listing. Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Hunt & Hunt (2007), "M-35 Along the Green Bay Shore".

- ^ "MDOT Declares UP Road as Heritage Route". Negaunee, Michigan: WLUC-TV. August 28, 2007.

- ^ Kent, AnnMarie (October 9, 2017). "UP Highway Named Newest Pure Michigan Byway". UpNorthLive. Traverse City, Michigan: WPBN-TV. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ "US 2 Relocation Project Finally Finished in '98". Iron County Progress. February 24, 1999.

- ^ a b National Park Service (July 9, 2010). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Johnston, Louis & Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, Lisa M. (May 17, 2012). "Twin Falls Bridge Nominated". The Daily News. Iron Mountain, Michigan. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ Michigan State Highway Department (1933). Plan and Profile of Proposed Federal Aid Project No. E 471 State Line-Iron Mountain-Interstate Bridge. Dickinson County. Breitung Township (PDF) (Map). Scale not given. Lansing: Michigan State Highway Department. p. 5. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Sparpana, Joe (April 8, 2011). "Historic Twin Falls Bridge Turns 100". The Daily News. Iron Mountain, Michigan. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ "Twin Falls Bridge on Historic Places List". The Daily News. Iron Mountain, Michigan. January 7, 2013. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ Gardner, Dawn (October 13, 2003). "Sturgeon River Bridge Will Open to US 2 Traffic Tuesday" (Press release). Michigan Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (May 9, 2002). "US 2–Sturgeon River". Michigan's Historic Bridges. Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Hunt & Hunt (2007), "Manistique—Siphon Bridge and Water Tower".

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (February 13, 2007). "Road and Highway Facts". History and Culture. Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ^ Hyde (1993), p. 132.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (May 9, 2002). "US 2–Cut River". Michigan's Historic Bridges. Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Hunt & Hunt (2007), "Epoufette—Cut River Bridge and Picnic Area".

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (May 13, 2002). "Mackinac Trail–Carp River". Michigan's Historic Bridges. Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Hyde (1993), p. 104.

- ^ Hyde (1993), pp. 102–4.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (May 9, 2002). "I-75 BR (Ashmun St.)–Power Canal". Michigan's Historic Bridges. Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ a b "US 2 Business Route Through Ironwood". The Bessemer Herald. August 14, 1942. p. 7. Retrieved November 9, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Google (April 18, 2011). "Overview Map of Bus. US 2" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

External links

[edit] Geographic data related to US 2 in North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to US 2 in North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan at OpenStreetMap- US 2 at Michigan Highways

- "US 2 Is Not A Freeway" at Michigan Highways

- Bus. US 2 at Michigan Highways

- Iron County Heritage Trail (Western Upper Peninsula Planning & Development Region)

- U.S. Highways in Michigan

- U.S. Route 2

- Lake Superior Circle Tour

- Lake Michigan Circle Tour

- Transportation in Gogebic County, Michigan

- Transportation in Iron County, Michigan

- Transportation in Dickinson County, Michigan

- Transportation in Menominee County, Michigan

- Transportation in Delta County, Michigan

- Transportation in Schoolcraft County, Michigan

- Transportation in Mackinac County, Michigan